[Ed. Note: This article is part of a collection of essays entitled “Critical Reflections on the 80th Anniversary of the End of World War II” published in August 2025.]

Keywords: World War II, World War I, World War III, commemoration, memory

The 80th anniversaries of the end of World War II – Victory in Europe Day on 8th May and Victory over Japan Day on 15th August – remind us of the immense suffering caused by the greatest conflict in human history. But they also raise questions about the time in which we live today. What is the meaning of the end of World War II 25 years into the twenty-first century? Are we still living in the post-World War II period? What are the ‘lessons’ drawn from the conflict?

The current world economic and political order is a lasting legacy of World War II. Often heard today are cries that the ‘rules based international order’ established 80 years ago with the end of World War II is giving way to a return to the ‘might is right’ order of the high noon of imperialism from the nineteenth century to the mid-twentieth century. America under Donald Trump, Russia under Valdimir Putin, and China under Xi Jinping are said to be at the forefront of this change.

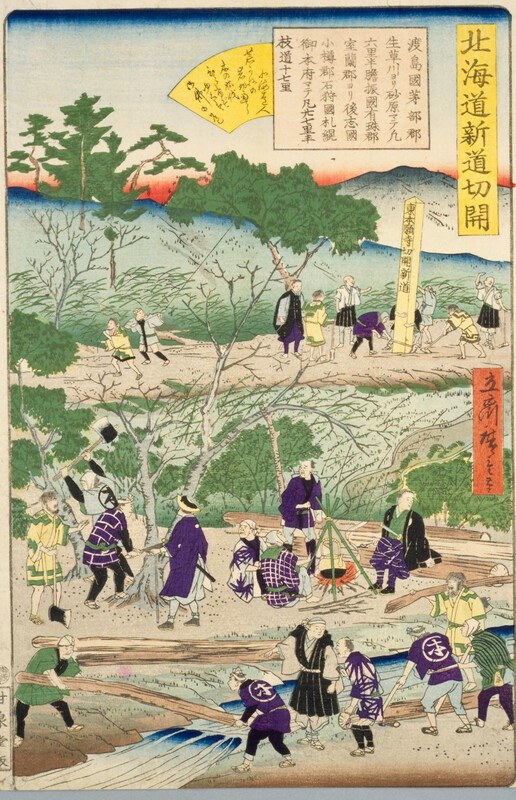

Looking back, historian Richard Overy in 2021 described World War II as ‘the last imperial war’.1 Germany, Italy, and Japan sought to establish global empires. However, the war, fought by the Allies in the name of freedom and self-determination, undermined imperialism and the idea that political control could be extended by one state over another.2 In the decades after the war, the established European empires were dismantled as people preferred to exercise their will through the nation-state rather than live in an empire.

In 1945, at the urging of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the United Nations was founded to allow nation-states, irrespective of their size and power, to be treated equally according to internationally agreed-upon rules. Key international economic institutions were established to help prevent another Great Depression, which was widely seen as having led to the rise of Nazism in Germany and militarism in Japan. In 1944 at the Bretton Woods conference the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank were created. Later in 1947 the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade was formed – as the predecessor of the World Trade Organization. These institutions were designed to prevent the disastrous tariff wars and laissez faire economic policies that had helped turn a recession into a Great Depression.

The continued role of these international political and economic institutions that were set up to prevent a repeat of another world war suggest that 80 years on we still very much live in what has been called the post-World War II period, although the term fell out of use to describe the present at the end of the Cold War and the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991. The post-World War II period has also been called ‘the long peace’.

The world has been in this place before. The ‘long peace’ of the post-World War II period is reminiscent of what was called ‘the century of peace’ of the nineteenth century. In 1815, after the Napoleonic Wars, the great powers at the Congress of Vienna, established an international order that ensured ‘a century of peace’ from another great war, lasting until the outbreak of World War I in 1914. The Congress of Vienna created a balance of power system that was designed to prevent large scale wars. In the early twentieth century, the great powers grew less committed to the existing balance of power, unwittingly stumbling, or in the words of historian Christopher Clark, ‘sleepwalking’ into a great war that none of them wanted – World War I.3 The disaster of World War I helped lay the basis for the catastrophe of World War II, which emerged out of the militarism fostered in the interwar period.

In the twenty-first century, hardly any historians and political scientists see the current situation as similar to the outbreak of World War II with the leaders of Germany, Italy, and Japan wanting a great war in order to build their empires. Instead, most argue that the world is in danger of ‘sleepwalking’ into another catastrophic conflict like the world did at the outbreak of World War I. None of the great powers of the twenty-first century want a catastrophic conflict but may unwittingly trigger one through their actions. Some political scientists see a likely repeat of great power conflict. Graham Allison argued that in history there existed a ‘Thucydides’s trap’, which meant that when one great power was on the rise and another was the ruling dominant power that great wars often resulted. In the twenty-first century, he saw China and America as playing these roles, which go back to the rivalry between Sparta and Athens, as documented by the Ancient Greek historian Thucydides.4

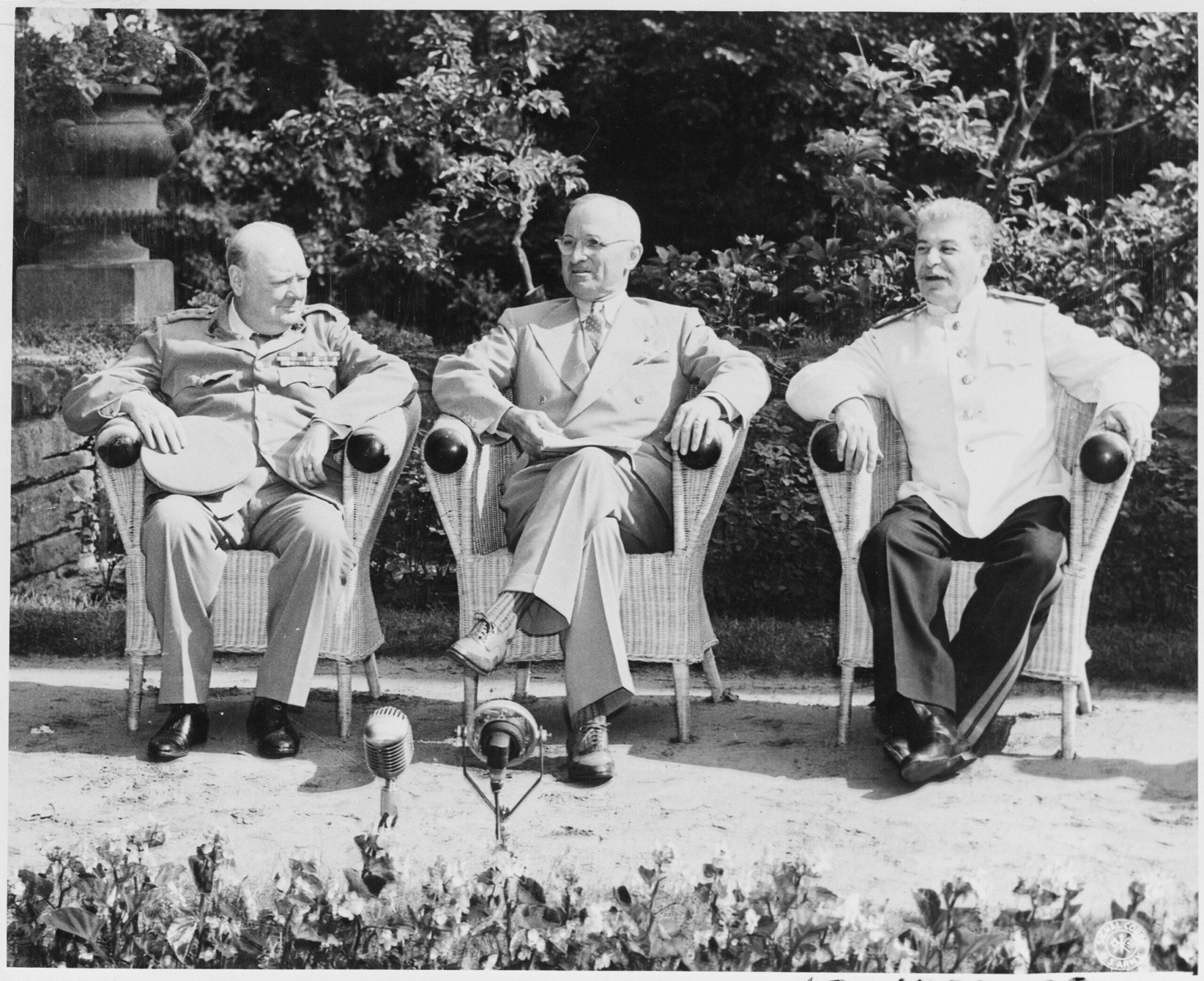

World War II has offered many lessons, as indeed does the history of the violent and bloody twentieth century. It is perhaps no surprise that in school history curriculum around the world, the international history of the twentieth century, focusing on the causes and consequences of World War II, figures so prominently. Today, school children analyze the decisions of leaders Neville Chamberlain, Winston Churchill, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry S. Truman, Joseph Stalin, Adolf Hitler, Benito Mussolini, Hideki Tojo, and Emperor Hirohito.

However, World War II and its lessons are not remembered the same across all the countries. In many Western democracies, the lessons include how divided democracies unable to solve the plight of their peoples can leave themselves wide open to the rise of dictators claiming to have the solutions if they are just given absolute power. Another lesson drawn from the conflict in Western democracies is that deterring aggression is better than appeasing it and having to fight a major conflict later. In Germany and Japan, World War II is a reminder of the dangers of militarism. However, in China, memories of World War II are used to stoke nationalism as it is perceived to be part of China’s ‘Century of Humiliation’ that the Chinese Communist Party uses to justify its own military build-up. In Russia, what is called the ‘Great Patriotic War’ is similarly used by Putin’s regime to mobilize the population behind his military aggression in Ukraine. Even within countries there are divergent lessons and memories of World War II. In Japan, the right wing sees Japan’s actions during the war as helping Asian countries free themselves from Western imperialism.

Yet despite these conflicting lessons and memories, the commemorations of the events of World War II have all shared the hope that the bloodiest conflict in human history not be repeated in the twenty-first century. Perhaps, this is the conflict’s most important lesson and greatest legacy.

Nonetheless, the question remains whether a world that is well into the twenty-first century can heed this lesson. Or is it sleepwalking into a great war? Can our focusing on the lessons of World War II help us to avoid what led to World War I? History suggests it may be possible. Remembering the past can play a role. During the Cold War, the memory of the destruction of World War II was still vivid and no leaders and their peoples wanted to plunge themselves into World War III. Maybe we can take this anniversary to reflect on ways that will help us to avoid a great war or military conflict in the twenty-first century, despite the conflicts that have emerged so far, such as the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the numerous wars in the Middle East.

Notes:

- Richard Overy, Blood and Ruins: The Last Imperial War, 1931-1945 (London: Penguin Random House, 2021), see Chapter 11: ‘Empires into Nations: A Different Global Age’, pp. 826-878.

- Keith Lowe, The Fear and the Freedom: How the Second World War Changed Us (London: Viking, 2017), pp. 6-7.

- Christopher Clark, The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914 (London: Allen Lane, 2012).

- Graham Allison, Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’s Trap? (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2017).