The Tokyo Tribunal, Justice Pal and the Revisionist Distortion of History

Nakajima Takeshi1

I. The Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal and Historical Revisionism in Post-War Japan

Since the mid 1990s, Japan’s neonationalist forces have made important gains: in education, culture and politics, as manifested notably in the activation of the Japanese Society for History Textbook Reform and the popularity of the best-selling comic book Sensōron (On War) by cartoonist Kobayashi Yoshinori.

Japanese historical revisionists have contrasted their approach with what they term the ‘Tokyo Trial view of history’ and the ‘masochistic view of history’. These revisionists regard as ‘masochistic’ any characterisation of Japan’s military advances in Asia during the pre-World War II period as an ‘invasion’. And they claim a ‘spell’ lingering from the International Military Tribunal for the Far East (‘Tokyo Tribunal’) underlies this ‘masochistic view of history’. Arguing that the Tokyo Tribunal created and disseminated a false perception of the Greater East Asia War as ‘the war in which the liberal Allies defeated a fascist Japan’, the revisionists hold that denouncing and rejecting the Tribunal is the key to shaking off this ‘masochistic view of history’.

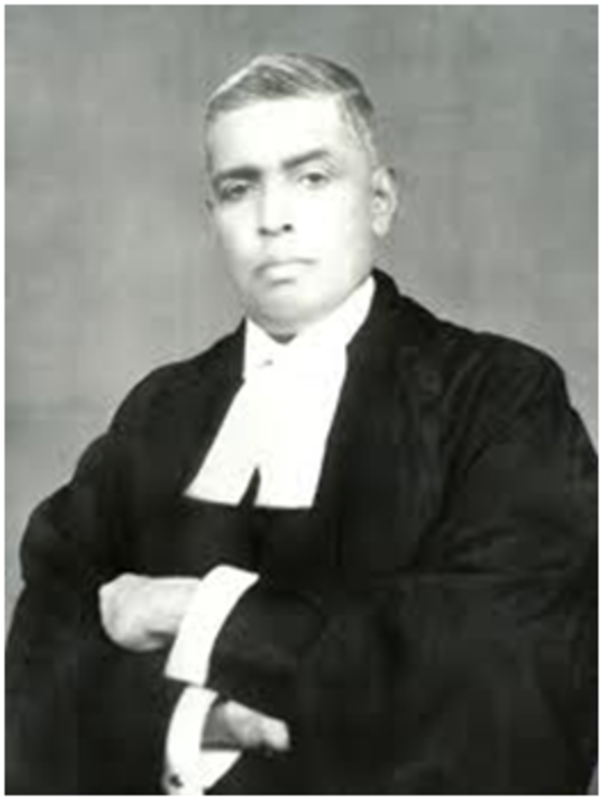

In their discourse on the denial of the Tribunal, revisionists frequently invoke the so-called ‘Pal Judgment’. An Indian judge participating in the Tokyo Tribunal, Radhabinod Pal issued a Dissenting Opinion entitled Dissentient Judgment of Justice Pal, which asserted that all Japanese Class A defendants at the Trial were innocent of crimes. Since the Tribunal’s language department omitted the category ‘dissentient’, the Opinion became widely known in Japan as the ‘Pal Judgment’.

However, the Opinion is often presented without a thorough examination of its content. Instead, only the decontextualised conclusion — that the Japanese suspects were not guilty — is singled out. In 2007, I published Pāru Hanji: Tōkyō Saiban hihan to zettai heiwa-shugi (Justice Pal: Criticism of the Tokyo Trial and Absolute Pacifism) in order to draw attention to misreadings of the ‘Pal Judgment’. While the book was well received, it also became a target of historical revisionists, such as Kobayashi Yoshinori, and was subjected to their severe bashing.

Based on this book, this article analyses Justice Pal’s theory in his Dissenting Opinion and examines the philosophy behind it. I also introduce an overview of how Justice Pal’s Opinion first became misinterpreted by Japanese historical revisionists, in order to explain how current revisionist discourse on the Opinion has been shaped.

|

Justice Pal |

II. Theory of Justice Pal’s Dissenting Opinion

Based on the principle of non-retroactivity of law, Justice Pal, first of all, explicated his criticism of the Tribunal’s ex post facto judgment in his Dissenting Opinion. He affirmed that the alleged ‘conventional war crimes’ by the Japanese defendants came within the jurisdiction of the Tribunal because they were already classified as crimes in pre-existing international law. However, Justice Pal opposed prosecution for ‘crimes against peace’, and ‘crimes against humanity’, as defined in the Tribunal’s Charter,2 because these crimes had no previous grounds in international law. If the defendants were to be found guilty of crimes which did not exist in international law when the alleged acts were actually executed, Pal said, then ‘the Tribunal will not be a “judicial tribunal” but a mere tool for the manifestation of power’.3 He highlighted the distinction between justice and politics, and severely criticised the subjection of the Trial to the political goals of state leaders.

Justice Pal objected to the introduction of an ex post facto law at the Tribunal because he believed that by ruling on ex post facto law, international society would not be bound by a common understanding against war. Instead, it would subscribe to an understanding that the victors of wars were entitled to judge the defeated while disregarding the rules of international law. Thus, he argued that if the Tokyo Tribunal invoked an ex post facto law it would eventually foment the expansion of wars of aggression and a breakdown of the foundation of international order, rather than lead toward the eradication of war. He stressed the importance of genuine legal processes and the establishment of the rule of law as follows:

Such a trial [a tribunal with ex post facto powers?] may justly create the feeling that the setting up of a tribunal like the present is much more a political than a legal affair, an essentially political objective having thus been cloaked by a juridical appearance. Formalized vengeance can bring only an ephemeral satisfaction, with every probability of ultimate regret; but vindication of law through genuine legal process alone may contribute substantially to the re-establishment of order and decency in international relations.4

He questioned the legitimacy of the Tokyo Charter, which was promulgated on 19 January 1946 and established the Tribunal. In adding to ‘conventional war crimes’, the Charter upheld new crimes that did not have a foundation in pre-existing international law: ‘crimes against peace’ and ‘crimes against humanity’. Justice Pal denounced this charter as a transgression of the fundamental rules of international law. He said a charter establishing an international court, regardless of who sets it up or staffs it, ‘does not define the crime but only specifies the acts the authors whereof are placed under the jurisdiction of the Tribunal’.5 He explained that the Tokyo Charter ought to decide merely what matters would come up for trial before the Tribunal. Whether or not these acts constituted any crime should be left open for determination by the Tribunal with reference to the appropriate laws. From this point of view, he strongly condemned the Tokyo Charter as widely departing from the fundamental rule of jurisdiction.

|

The Justices (Pal on the left) |

According to Justice Pal, the victors had the right to set up a special court, and therefore the establishment of a charter itself was not problematic; however, the victors had no right to legislate the creation of new crimes in international law.

He also said that the judges of the Tribunal were ‘competent to investigate the question whether any provision of the Charter is or is not ultra vires’6 in the reflection of international law, because the Charter of the Tribunal itself derives its authority from international law.

As a judge of the Tribunal, Justice Pal concluded that the provisions regarding ‘crimes against peace’ and ‘crimes against humanity’ were ex post facto laws and violated the prohibition on non-retroactivity in international law. Further, Pal examined the historical process on the ‘overall conspiracy’ which the prosecution defined as a premise of the alleged ‘crimes against peace’, and criticised the prosecutors’ arguments. He intended to prove that so-called ‘crimes against peace’ were invalid both from jurisprudential and historical perspectives.

Justice Pal, however, did not deny the legitimacy of the whole Tribunal. He affirmed the value of examining the alleged acts for ‘conventional war crimes’ that would come to the court. ‘A war’, he said, ‘whether legal or illegal, whether aggressive or defensive, is still a war to be regulated by the accepted rules of warfare. No pact, no convention has in any way abrogated jus-in-bello.’7

Justice Pal’s viewpoint on the Tokyo Tribunal was reflected in how he structured his Dissenting Opinion. ‘Pal’s Judgment’ consists of seven chapters: Part I, Preliminary Question of Law; Part II, What Is ‘Aggressive War’; Part III, Rules of Evidence and Procedure; Part IV, Over-all Conspiracy; Part V, Scope of Tribunal’s Jurisdiction; Part VI, War Crimes Stricto Sensu; and Part VII, Recommendation. An important point to note here is that he placed ‘Scope of Tribunal’s Jurisdiction’ after the chapter about the alleged ‘overall conspiracy’. In Part IV, which occupies the largest volume in the Opinion, he explained that the ‘overall conspiracy’, which was presented as a premise of ‘crimes against peace’ by the prosecution, was not established as a crime in international law. Therefore, the Indictment itself was invalid before the judgment on the question of innocence or guilt.

The only alleged acts by the Japanese defendants he saw as triable by the Tribunal from a genuine judicial point of view were ‘conventional war crimes’, because these crimes were defined in pre-existing international law at the time the alleged acts were carried out. Whether the accused were guilty or not would be open to the Tribunal, so he found no conflict in hearing the alleged acts at the Tribunal. This was the reason Pal clarified the scope of the Tribunal’s jurisdiction before the section on ‘conventional war crimes’ and defined the scope of jurisdiction as extending back to the Sino–Japanese War of 1894-95.

In Part VI, ‘War Crimes Stricto Sensu’, he examined the establishment of criminality in what he called the ‘atrocities’ conducted by the Japanese Imperial Army. Regarding the Nanjing Massacre, although he premised that wartime propaganda from hostile sources was blended in with the evidence submitted to the Tribunal, and therefore, it may not have been safe to accept the entire story, he concluded that the fact that atrocities were executed by the Imperial Army was unshakable. He said as follows:

Keeping in view everything that can be said against the evidence adduced in this case in this respect and making every possible allowance for propaganda and exaggeration, the evidence is still overwhelming that atrocities were perpetrated by the members of the Japanese armed forces against the civilian population of some of the territories occupied by them as also against the prisoners of war.8

And further:

Whatever that be, as I have already observed, even making allowance for everything that can be said against the evidence, there is no doubt that the conduct of the Japanese soldiers at Nanking [Nanjing] was atrocious and that such atrocities were intense for nearly three weeks and continued to be serious for a total of six weeks as was testified to by Dr. Bates.9

Justice Pal then continued to investigate whether the facts supporting the accusation that the Class A defendants ordered, authorised and permitted others to commit those acts, and such persons actually committed them; and if the facts supported the conclusion that the Class A defendants deliberately and recklessly disregarded their legal duty to take adequate steps to prevent the commission of such criminal acts.

On the first point, while characterising the alleged atrocities as ‘devilish and fiendish’, he concluded that no evidence of any alleged order, authorisation or permission had been found. He judged that the atrocities including the Nanjing Massacre were determined and executed by the Army soldiers on the ground, and that by the time he wrote his book, the people who were responsible for the acts had already been executed as Class B and Class C war criminals.

It should be remembered that in the majority of cases ‘stern justice’ has already been meted out by the several victor nations to the persons charged with having actually perpetrated these atrocious acts along with their immediate superiors. We have been given by the prosecution long lists of such convicts.10

And further:

But those who might have committed these terrible brutalities are not before us now. Those of them who could be got hold of alive have been made to answer for their misdeeds mostly with their lives.11

On the issue of foul acts, for which the defendants would be found guilty if it were proven that the atrocities by Japan became intense and were carried out on a larger scale due to the defendants’ ‘intention’ or ‘negligence’, Justice Pal said, ‘these commanders [the Japanese defendants] were legally bound to maintain discipline in the army and to restrain the soldiers under their command from perpetrating these atrocities’. He continued as follows:

It is true that a commanding officer is not liable for the acts of those in his command merely because he is their superior officer; but, because of his great control over them, he should be responsible for such acts of theirs which he could reasonably have prevented. He had the duty to take such appropriate measures as were in his power to control the troops under his command.12

However, Justice Pal concluded that the evidence submitted to the Tribunal was not sufficient to prove that the accused Class A suspects were criminally responsible for the acts of these troops.

It is a fact that Justice Pal strongly condemned the atrocities by the Japanese Imperial Army, including the Nanjing Massacre, as determined by facts. However, he concluded that the criminal responsibility of Japanese Class A suspects for the atrocities could not be proven due to a lack of evidence.

Justice Pal next took up Japan’s ‘maltreatment of prisoners of war’. In examining the alleged offences, he spent many pages on the cases of the Bataan Death March in the Philippines and the construction of the Burma–Thai Railway. He strongly denounced acts committed by the Army in both cases.

Regarding the Bataan Death March, he said it was ‘really an atrocious brutality’ and ‘I do not think that the occurrence was at all justifiable’.13 Regarding the treatment of prisoners of war employed for the Burma–Thai Railway construction, which directly related to Japanese war operations, he said that the accused Tōjō Hideki, Japan’s Prime Minister from October 1941 to July 1944, was ‘fully responsible’.14 He also stated that their treatment of prisoners was ‘inhuman’.15

He continued, though, by saying that the March was ‘an isolated instance of cruelty’16 and that the employment of prisoners of war for the railway construction was a ‘mere act of state’,17 and eventually concluded that the evidence did not satisfy him that the alleged acts were conducted under the ‘order, authorization or permission’ of the accused.18 In other words, he concluded that the accused could not be found criminally liable due to the lack of evidence.

A point that should be noted is the difference in his argumentations for ‘crimes against peace’ and ‘conventional war crimes’. Regarding ‘crimes against peace’, he presented his view that the charges were based on an ex post facto law. Additionally, the ‘overall conspiracy’ which the prosecution tried to establish as a premise for ‘crimes against peace’ was not found. Therefore, the Indictment for ‘crimes against peace’ itself was fundamentally not established. On the other hand, in the matter of the alleged offences of ‘conventional war crimes’, wherein Justice Pal approved the grounds in international law and approved of them being heard by the Tribunal, Pal investigated the alleged crimes in accordance with international law and eventually concluded that the evidence presented to the Tribunal was not sufficient to establish the criminal responsibility of the defendants for the accused acts.

III. Justice Pal’s View on History and his Opinion on Legislation

In Part IV of his Dissenting Opinion, Justice Pal examined the alleged ‘overall conspiracy’. The prosecution claimed that the defendants had conspired, and that the accused crimes were part of Japan’s overall plot to occupy Manchuria, the whole of China and eventually the entire world. While he criticised Japan’s acts allegedly executed under the ‘overall conspiracy’ — including the Zhang Zuolin (Chang Tso-lin) Assassination Incident and Manchurian Incident in Japan’s steps toward the Sino–Japanese War — Pal pointed out that Japan was an imitator of Western Imperialism and argued that both Japan and the Allied countries were morally responsible for their actions.

First, he took up the Zhang Zuolin Assassination Incident by the Japanese Kwantung Army, on 4 June 1928. The Incident was plotted by Kwantung Army officer Colonel Kawamoto Daisaku, and the leader of the Fengtian Army, warlord Zhang, was killed. Kawamoto had planned to conquer Manchuria by taking advantage of the confusion that would have occurred after the Incident. However, this failed as the chiefs of staff of the Kwantung Army were not informed of his plan. Moreover, the Fengtian Army did not respond to this provocation. In the Tokyo Tribunal, the prosecution claimed that the Incident was the first act in the defendants’ ‘overall conspiracy’ in which they consistently and carefully planned and prepared acts or wars of aggression such as the Manchurian Incident, the Sino–Japanese War, up to and including the Greater East Asia War.19

Justice Pal disagreed with their claim. He said, ‘Chang Tso-lin’s murder was planned and executed by a certain group of Kwantung army officers. There is absolutely nothing to connect this plan or plot with the alleged conspiracy.’20 He continued, ‘[p]lanning any murder and executing the same are certainly reprehensible by themselves. But we are not now trying any of the accused for that dastardly act of murder. We are to see what connection this story has with any relevant issue before us.’21

Having described the Zhang Zuolin Assassination Incident as a ‘dastardly act of murder’, he said that Kawamoto and others who were involved in it were ‘reprehensible’.22 However, from a legal point of view, he stressed the necessity of proof to show the ‘dastardly act’ by the Army officers was a part of the ‘overall conspiracy’ by the accused Japanese leaders in Tokyo. After examining the evidence, he came to the conclusion that although it was true that many officers in the Kwantung Army intended to ‘occupy Manchuria’ at that time, the Incident was planned and executed by a limited group of people and the evidence given in the Tribunal failed to establish that there was an ‘overall conspiracy’ behind the Incident. He said the alleged ‘crimes against peace’ could not be established simply by connecting irrelevant cases to ‘the whole story’.23

What should be confirmed here is that although he argued the Incident was not a part of a ‘conspiracy’, he sharply criticised the Incident itself.

He next addressed the Manchurian Incident. He first discussed the Mukden Incident (or the Liutiaogou Incident), which occurred at the outset of the Manchurian Incident, and argued that it was difficult to determine from the evidence that the Mukden Incident was a conspiracy among the Japanese defendants in the Tokyo Tribunal. He said:

Even accepting the evidence of TANAKA and OKADA that the Mukden Incident of 18 September, 1931 was planned by some young officers of the Kwantung Army, I do not find any substantial evidence to connect any of the accused with that group or clique. The position in my opinion still remains as was found by the Lytton Commission. The incident might have been the result of a design on the part of some unknown army officers, yet those who acted on the strength of the incident might have acted quite bona fide.24

The gist of his logic here is the same as with the Zhang Zuolin Assassination Incident: although the Mukden Incident might have been a plot by particular officers of the Kwantung Army, the connection between them and the accused leaders was not established. As a consequence, it was difficult to view the Incident as part of an alleged ‘overall conspiracy’.

Again this does not mean Justice Pal was uncritical regarding the Incident or the Kwantung Army: ‘The military developments in Manchuria after September 18, 1931, were certainly reprehensible. Despite the unanimous opinion of the Cabinet that the operation must cease immediately, the expansion continued.’25

He determined the Manchurian Incident was ‘reprehensible’ and saw the actions of the Army in ignoring the Japanese Cabinet order and initiating the Incident as a problem. Still, he insisted that the circumstances did not prove a conspiracy among those accused: ‘No one would applaud such a policy. No one would perhaps justify such a policy. Yet this need not drive us to a theory of conspiracy’.26

In this Chapter, he further discussed the Western Powers’ political and military acts in the international community at that time. While presenting the view that the Kwantung Army and the Western countries were companions in crime, he condemned the Western Powers for launching accusations against Japan while ignoring their own responsibility for committing acts that were similar to those of the Japanese Army.

First, he criticised Japan’s establishment of Manchukuo, calling it an ‘elaborate political farce’,27 forced upon the Chinese people by Japan’s military occupation of Manchuria:

[T]he power to play the farce of ‘Manchukuo’ on the Manchurian stage, as well as the power to seize control over Manchuria had been acquired by the Japanese manu militari. As has been observed in the review of International Affairs, the military conquest and occupation of Manchuria by the Japanese Army was the real foundation of the Japanese position in Manchuria in 1932; and the whole world was aware that this was the fact. The Japanese were apparently prepared to defy the world’s opinion and to risk the consequences of the world’s disapproval in order to keep their ill-gotten gains.28

Why then, he asked, did Japan not simply proclaim the annexation of Manchuria instead of persisting in a farce. Justice Pal saw the answer in the process of Japan’s modernisation itself, which was a continuous imitation of the West: ‘It is considered probable that it might be attributed in part to an anxiety to imitate Western behaviour — an anxiety had become an idee fixe in Japanese minds since the beginning of the Meiji era’.29

Justice Pal then critically examined Western Imperialism, which, he asserted, Japan had imitated. Quoting the Survey of International Affairs 1932, he turned the target of the criticism toward the colonial policies of Western Powers:

Was it not Western Imperialism that had coined the word ‘protectorate’ as a euphemism for ‘annexation’? And had not this constitutional fiction served its Western inventors in good stead? Was not this the method by which the Government of the French Republic had stepped into the shoes of the Sultan of Morocco, and by which the British Crown had transferred the possession of vast tracts of land in East Africa from native African to adventitious European hands?30

For Justice Pal, Japan’s ‘farce’ was nothing but the result of imitating Western fashions of imperialism. From this point of view, he questioned why only Japan’s establishment of Manchukuo could be assessed as ‘aggression’. Weren’t Western countries morally guilty as well in practicing colonialism? If the acts of aggression by Western countries were not charged as crimes, why was the establishment of Manchukuo by Japan?

Justice Pal further quoted the Survey of International Affairs 1932:

Though the Japanese failed to make the most of these Western precedents in stating their case for performing the farce of ‘Manchukuo’, it may legitimately be conjectured that Western as well as Japanese precedents had in fact suggested, and commended, this line of policy to Japanese minds.31

By saying, ‘[i]t may not be a justifiable policy, justifying one nation’s expansion in another’s territory’,32 he emphasised that both Japan and the Western countries were morally responsible for the colonisation of other nations. Justice Pal explained that Japan was at that time possessed with a ‘delusion’ and believed that the country would face death and destruction if it failed in acquiring Manchuria.33 Pal regarded this as the reason for Japan’s attempts to establish interests which it saw as necessary for its very existence. Justice Pal said that carrying out a military operation driven by ‘delusion’ was not unique to Japan as it had been repeatedly practised on a large scale by Western countries for many years. Saying, ‘[a]lmost every great power acquired similar interests within the territories of the Eastern Hemisphere and, it seems, every such power considered that interest to be very vital’, Pal argued that Japan had the ‘right’ to argue that the Manchurian Incident was necessary for the sake of ‘self-defense’.34 Japan claiming national ‘self-defense’ in regard to its territorial expansion in China was in step with international society at the time, Pal said, and thus Japan’s actions stemmed from the ‘imitation’ of an evil practice of Western imperialism. Based on this premise, he concluded: ‘The action of Japan in Manchuria would not, it is certain, be applauded by the world. At the same time it would be difficult to condemn the same ascriminal.’35

The important thing to notice here is that Justice Pal did not conclude that Japan’s actions were justifiable. As mentioned above, he criticised the Manchurian Incident as ‘reprehensible’, and the establishment of Manchukuo as an ‘elaborate political farce’ based on ‘delusion’. But, at the Tribunal Justice Pal strove to show his disapproval of the prosecution’s intention to treat Japan’s actions as if they were carried out under an alleged ‘overall conspiracy’, by presenting the complexity in the reasons why Japan pushed herself forward to the occupation of Manchuria.

From his historical point of view, Justice Pal saw the fundamental cause for Japan’s acts of aggression as rooted in colonialism by Western countries. He questioned whether the visits by the US Navy’s Commodore Matthew Perry in the 1850s and the conclusion of unequal treaties with Western Powers such as the US, Russia, Great Britain, France and Holland in the late Edo Era was a fundamental cause for Japan’s imperialism, and he argued that Japan’s steps toward imperialism were not ‘blameworthy’.

Justice Pal said:

Then follows Japan’s struggle for getting revision of these treaties. This struggle continued till the year 1894. During this period, Japan made every effort to master the great contributions of western thought and science. Perhaps Japan also realized that in the world in which she had been thus forced to appear, right and justice were measured in terms of battleships and army corps.

The Japanese effort to get these treaties revised were certainly not blameworthy.36

He argued that Japan endeavoured to achieve rapid modernisation and employed Western methods in order to assure the revision of unequal treaties with the Western Powers. Japan also built up its military power during the process by ‘imitating’ the Western Powers’ imperialism. While Justice Pal did regard the manner in which Japan proceeded with its modernisation as problematic, he also questioned whether the Western Powers could really condemn Japan’s imitating them if the purpose in doing so was to revise the unequal treaties imposed by the Western Powers: ‘We cannot afford to ignore the possible effects upon Japan of this long struggle for the revision of such treaties’.37

This observation can be seen in Justice Pal’s argument on the Sino–Japanese and Russo–Japanese Wars. He saw these as part of a power struggle among the major powers rather than unilateral ‘aggressions’ by Japan. For Pal, it was hypocritical for the Western countries to criticise as criminal Japanese actions, which were merely an ‘imitation’ of their own. ‘After the Russo–Japanese war, Japan seemed to follow closely the precedents set by Europe in its dealings with China’,38 said Pal in reference to Japan’s steps toward expansion of colonial territories after the Sino–Japanese and the Russo–Japanese Wars. He said that if Japan’s colonialism was deemed problematic, then all colonialism by the Western Powers ought to be similarly regarded. However, he pointed out, Western Powers did not criticise Japan’s actions as ‘aggression’ while the acts were ongoing. He said, ‘Great Britain renewed and strengthened the Anglo–Japanese Alliance at that time and the contemporary powers did not condemn Japan’s action as aggressive’.39

During World War I, ‘Japan, as a faithful ally, rendered valuable assistance in an hour of serious and very critical need to the Allied Powers’.40 The Allied Powers were helped by support from Japan. His question was how these Western countries could blame the steps taken by Japan.

Pal presented the following view of history:

Japan was a country without any material resources of her own. She started on her career when ‘Western Society had come to embrace all the habitable lands and navigable seas on the face of the planet and the entire living generation of mankind’.

The Japanese emulated the western powers in this respect but unfortunately they began at a time when neither of the two essential assets, ‘a free-hand’ for their ability and a world-wide field, was any longer available to them. The responsibility for what Japan was thinking and doing during the period under our consideration really lies with those earlier elder statesmen of Japan who had launched her upon the stream of westernization and, had done so, at a moment when the stream was sweeping towards a goal which was a mystery even to the people of the west themselves.41

Looking back at the path of Japanese modernisation, Justice Pal cast sharp criticism and a caustic view on the Western countries. By presenting this sort of irony, he intended to criticise Western colonialism and to assert that the Western countries and Japan were in cahoots.

Regarding the start of the war between Japan and the US, Justice Pal blamed the direction of diplomatic policy on the US more than the Japanese. In his view, US diplomacy, as represented especially in the Hull Note,42 eventually cornered Japan. He said, ‘[t]he evidence [submitted to the Tribunal] convinces me that Japan tried her utmost to avoid any clash with America, but was driven by the circumstances that gradually developed into the fatal steps taken by her.’43

In his Dissenting Opinion, Justice Pal repeatedly quoted International Affairs by the British Royal Institute of International Affairs, the British historian Arnold J Toynbee, and Professor of International Law at the University of London Georg Schwarzenberger. He challenged the one-sided accusations by the prosecution against Japan by highlighting that even some in the Western world had accused the Western superpowers.

Regarding the Hull Note in his Dissenting Opinion, Justice Pal quoted Memoirs of a Superfluous Man by Albert Jay Nock, published in 1943, as follows:

Even the contemporary historians could think that ‘As for the present war, the Principality of Monaco, the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, would have taken up arms against the United States on receipt of such a note as the State Department sent the Japanese Government on the eve of Pearl Harbor.’44

While condemning the US move, Justice Pal also criticised Japan’s problematic diplomacy:

There I pointed out why I could not accept the prosecution charge of treacherous conduct of the Japanese statesmen concerned. No doubt preparation for war was going on while the diplomatic negotiations were being held. But such preparations were being made by both sides. If the Japanese side ‘had little confidence that the Kurusu-Nomura negotiations would achieve their purposes’, I do not feel that the American side entertained any greater confidence in the diplomatic achievement.45

Japan prepared for war against the US while diplomatic talks between the two countries were ongoing. Justice Pal claimed this ‘treacherous design’ on the part of Japan was a serious matter. But, he pointed out that a similar ‘treacherous design’ was also seen on the US side, and therefore, both Japan and the US were equally responsible for the war. Regarding the prosecution’s accusations of a conspiracy, he argued that neither plan nor conspiracy existed behind the start of the war. He regarded Japan’s decision to make war against the US as not made in advance as a part of the alleged ‘overall conspiracy’, but rather made only during Japan’s diplomatic negotiations with the US, after which it merely executed the decision.

In summarising Part IV of his Dissenting Opinion, Justice Pal said: ‘The statesmen, diplomats and politicians of Japan were perhaps wrong, and perhaps they misled themselves. But they were not conspirators. They did not conspire.’46

Justice Pal described Japan’s actions following the Zhang Zuolin Assassination Incident as not justifiable. He also applied this assessment to Western colonialism. However, on the matter of an alleged ‘overall conspiracy’, he argued that each ‘isolated’ act by Japan had been purposefully framed by the prosecution to assert an ‘overall conspiracy’, as if Japan had managed the acts as part of a policy of aggression.47

Also, Justice Pal stressed that Japan should not be seen in the same way as Nazi Germany. According to his view, Tōjō and his group ‘might have done many wrong things; but, so far as the public of Japan is concerned, certainly by their behaviour towards them they did not succeed in reducing them to the position of terror-stricken tools without any free thinking or free expression. The population of Japan was not enslaved as in Hitler’s Germany.’48 He claimed that Japan did not have a dictator such as Hitler.49 The wars in the modern era were ‘not the result of any design by any particular individual or group of individuals’,50 said Pal. He explained that the ‘evil of warfare’ was transformed by a combination of factors.51

As mentioned earlier, Justice Pal criticised Japanese statesmen, diplomats and politicians with judgmental terms such as ‘misconception’ and ‘wrong’.52 Still he argued that as long as the claimed ‘overall conspiracy’ was not established from the evidence before the Tribunal, the alleged acts in the Indictment could not be found criminal. His argument was never ‘Japan was innocent’ or ‘affirming the Great East Asia War’. Moreover, what should be noted here is that if he absolved the suspects’ criminal responsibility he did not dismiss the moral responsibility of Japan. He strongly criticised Japan’s war crimes and analysed Japan’s historical process after the Manchurian Incident as critically as he did the colonisation of Western countries. Therefore it is obvious that the logic of neonationalists to infer ‘Japan’s innocence’ or ‘an affirmation of the Greater East Asia War’ from Justice Pal’s Dissenting Opinion is an obvious misreading as well as an unwarranted jump in logic.

IV. Justice Pal’s Thoughts

In his Dissenting Opinion, Justice Pal repeatedly expressed the importance of and hope for the establishment of ‘a system of international cooperation’.53

He said:

I doubt not that the need of the world is the formation of an international community under the reign of law, or correctly, the formation of a world community under the reign of law, in which nationality or race should find no place.54

For the strict practice of international law, the establishment of international society under a rule of law was necessary. Justice Pal strongly advocated the emergence of what he termed the ‘Super State’, which he believed would eradicate wars and overcome racial discrimination.55

Obviously, he did not believe the idea of the world commonwealth would be realised in the immediate future. He rather thought that the international social system ought to be transformed toward the ideal of a world commonwealth. He regarded the first step towards the world commonwealth as the establishment of an international agency with national sovereignty as its premise. He said that because such an international agency was not yet fully established, the practice of international law faced serious difficulties. In other words, without a Super State, there could exist no concrete executive power, and whether international law would be executed or not would after all be determined by the international affairs and power relations of the time. This was the reason why he stressed the importance of the early introduction and establishment of an international agency for the observance and execution of international law. And, he believed that a widening sense of humanity to develop the international agency into the ideal world commonwealth would stabilise the order of international society.

Justice Pal was a believer in humanism based on the philosophy of ‘dharma’ from ancient India. He advocated Gandhism, and dreamt of the day that human beings would establish ideals based ultimately on pacifism.

On his visit to Japan in 1952, Pal, asked to make speeches at different places in order to introduce the idea of unarmed neutrality in the world. Strongly opposed to Japan’s remilitarisation as then advocated by the US, he passionately advocated the teachings of Gandhi. Pal showed his resentment and disappointment toward a Japan whose dependence on the US was deepening, and he strongly criticised Japan as uncritically following the will of the US.

Visiting the Atomic Bomb Memorial in Hiroshima, he clearly expressed his bitterness toward Japan. On seeing the memorial’s inscription, ‘Let all the souls here rest in peace. For we shall not repeat the evil,’ Pal said:

Obviously, the subject of ‘we’ is Japanese. I do not see clearly what ‘the evil’ means here. The souls being wished to rest here are the victims’ of the Atomic Bomb. It is clear to me that the bomb was not dropped by Japanese and the hands of bombers remain bloodstained. … If not repeating the mistakes means not possessing weapons in the future, I think that is a very exemplary decision. If Japan wishes to possess military power again, that would be a defilement against the souls of the victims we have here in Hiroshima.56

|

The Cenotaph |

His anger toward the mentality of Japanese people in the post-war era was expressed in his remark. He condemned Japan’s remilitarisation corresponding to the will of the US, in light of US responsibility for the atomic bombing of Japan.

V. Misappropriation of Justice Pal’s Dissenting Opinion by Historical Revisionists

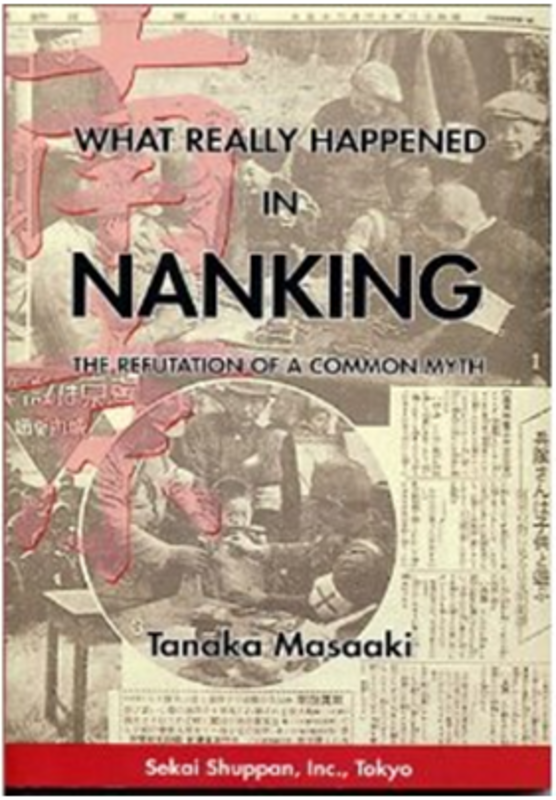

As explained above, Japanese post-war historical revisionists have ignored the kernel of Justice Pal’s argument and his thoughts outlined above, and instead repeatedly invoked his Opinion to support their positions. They have distorted parts of Justice Pal’s Dissenting Opinion for their own purposes, specifically to insist on ‘Japan’s innocence’ and support ‘the affirmative argument on the Greater East Asia War’ as well as their ‘criticism of the Tokyo Tribunal’ and their ‘criticisms of the masochistic view of history’. The serial arguments for example of Tanaka Masaaki, who advocates a reading of Justice Pal’s arguments as one that proves ‘Japan is not guilty’, were especially influential and became a foundation for further misreadings of Pal which continue to the present.

A writer and social activist, Tanaka was born in 1911, and developed his activities under the influence of ultra-nationalists such as Shimonaka Yasaburo and Nakatani Takeyo in the pre-war period. In 1933, Tanaka joined the newly established Greater East Asia Association that had General Matsui Iwane (who was later executed as a Class A war criminal held responsible for the Nanjing Massacre) as chairman. Tanaka was involved in editing the organisation’s paper, Greater East Asianism. Tanaka also served as Matsui’s secretary and was active as Matsui’s ‘right arm’ until Matsui was appointed Commander of the Japanese Expeditionary Forces and sent to China in 1937.

In April 1952, soon after the lifting of media censorship by the US occupation authorities, Tanaka published On Japan’s Innocence: The Truth on Trial, in which he offered his interpretation of Justice Pal’s Dissenting Opinion.57 In his book, Tanaka quoted Pal’s arguments in a generally accurate way then added his commentary. For example, on the Nanjing Massacre, he faithfully quoted Pal’s Opinion and his conclusion, ‘it is a plain fact that the Japanese military committed the atrocity’.58

|

However, Tanaka’s book title fundamentally distorts Justice Pal’s argument. First, since Pal’s Opinion criticised only ‘the criminal responsibility of Class A accused’, the object in the book title ought to be ‘On Class A Innocence’. It is important to note that Justice Pal found criminal responsibility in the cases of Class B and Class C war criminals. He did not discount all of Japan’s criminal actions.

Second, the term ‘innocence’ should be clarified. The central point is that Justice Pal found the Japanese Tokyo Tribunal defendants ‘innocent’ only in terms of international law. As quoted above, Justice Pal said, ‘Tojo and his group … might have done many wrong things’,59 and ‘[t]he statesmen, diplomats and politicians of Japan were perhaps wrong, and perhaps they misled themselves’.60 Pal held the Japanese leaders morally responsible for their actions even as he challenged the Tribunal’s jurisdiction. Therefore, it is not accurate to say that Pal found no responsibility among the Japanese leaders for the acts committed by the Japanese Army, or that they had no moral responsibility. From these points, at most the title should have been ‘On Class A War Criminals’ Innocence’.

Apart from the misleading title, I believe that Tanaka was generally accurate in presenting the essence of Justice Pal’s argument. Although some problems are recognised, neither arbitrary deletions nor distortions of Pal’s fundamental views were presented in his first book.

However, Tanaka’s next book, Justice Pal’s Discussion of Japan as Not Guilty, published in 1963 (and the best selling book of the year),61 contains obvious misreadings, falsifications, phrases that induce readers’ misunderstanding, and intentional omissions of, or obvious deviations from, Pal’s arguments.

For example, although in his Dissenting Opinion Justice Pal said ‘the hostility which commenced between China and Japan on July 7, 1937 cannot be denied the name “war”’,62 and that Japan’s acts after the Sino–Japanese War should be examined at the Tribunal, Tanaka claimed in his book that Justice Pal’s Opinion was that the scope of the Tribunal ought to be limited to the period between 7 December 1941 and Japan’s surrender.63

This is an obvious misreading or falsification that seriously distorts Justice Pal’s argument. Furthermore, Tanaka completely ignored Pal’s condemnation of the Zhang Zuolin Assassination Incident, the Manchurian Incident, and the establishment of Manchukuo. He also ignored the fact that Pal had confirmed the Nanjing Massacre as well as Japan’s atrocities in the Philippines and strongly criticised them. The sections in which Pal criticised these actions were among the most important in the development of his argument. Therefore, omitting these severe criticisms of Japan’s actions, which Pal termed ‘devilish and fiendish’,64 is a serious distortion.

It was at this time that Tanaka began to present his argument denying the Nanjing Massacre. Tanaka later, in 1980, became a main polemicist of the massacre deniers. Justice Pal’s Discussion of Japan as Not Guilty contained arbitrary interpretations, omissions and misreadings of Justice Pal’s Opinion in favour of Tanaka’s political views, which influenced similar arguments concerning Justice Pal’s Dissenting Opinion.

In 1964, a year after the publication of Justice Pal’s Discussion on Japan as Not Guilty, literature scholar Hayashi Fusao published his book Affirming the Greater East Asia War, which was subjected to much criticism. Hayashi presented his view of the hundred year’ war of East Asia in the book. Hayashi re-defined the period from the end of the Edo Era (1868) to the end of the Greater East Asia War (1945) as a ‘history of resistance’ of Japan and Asian countries against Western Imperialism. Hayashi used a chapter of his book to introduce Justice Pal’s Dissenting Opinion with quotations from Tanaka’s Justice Pal’s Discussion of Japan as Not Guilty. Hayashi ended the chapter as follows:

It is unnecessary to talk about the Greater East Asia War again. Japan lost beautifully. Future historians would write of Japan’s gallant fight, its brave spirit and its fate as a heroic chapter of the 20th century.65

Quoting Tanaka’s commentary in Justice Pal’s Discussion of Japan as Not Guilty — ‘[a]s long as Japanese people are indoctrinated in the sense of guilt that “Japan was the country which carried out embarrassing aggressive wars to face the world,” Japan will never have its true glory’66 — Hayashi drew on Justice Pal’s Opinion to support his thesis of the war as just. He especially highlighted Pal’s alleged view of the outbreak of war between Japan and the US to assert that the Greater East Asia War was legitimate.

In the face of an onslaught of revisionist interpretations of Justice Pal’s argument which sought to justify the Greater East Asia War, historian Ienaga Saburo responded in his 1967 paper, ‘The Fifteen Years’ War and Pal’s Dissentient Judgment’.67 Pointing out the inaccuracy of the term ‘Japan’s innocence’ and criticising the superficial and arbitrary use of Pal’s Opinion, Ienaga wrote that Pal’s Opinion was being distorted to strengthen a social atmosphere supporting the Greater East Asia War which had become increasingly dominant through the coordinated push of political power and civil forces.

He also said that the Opinion was grounded on anti-communist ideology and its argument was full of extremely distorted views. Richard Minear responded and Ienaga and Minear debated the issue. However, arguments that distorted Justice Pal’s Opinion in support of the neonationalist discourse continued to appear, and this trend has increased, especially since the late 1990s when Japan’s rightward drift became pronounced.

In 1997, a memorial monument to Justice Pal was erected at Kyoto Gokoku Shrine. It was established by the Committee for the Establishment of Justice Pal’s Memorial Monument, whose chairman was Sejima Ryuzo (a former Kwantung Army Staff Officer and former Supreme Adviser of Itochu Corporation). Its members included Kyoto Governor Aranamaki Teiichi and Kyoto City Mayor Masumoto Yorikane.

The establishment of the monument was followed by a similar statue of Pal at Yasukuni Shrine in 2005. Nambu Toshiaki, the shrine’s Chief Priest, said at the unveiling ceremony: ‘It is my earnest wish that the drift of masochism will end, and the day when the spirits of war dead may rest in peace comes as early as possible.’ This followed the homage to Pal beginning in 2002, at the Yushukan, the Japanese military and war museum within Yasukuni Shrine. Pal’s photographs and his remarks on his visit to Japan in 1952 were displayed in the context of criticising the ‘Tokyo Trial view of history’ and the ‘masochistic view of history’. A 1998 movie titled Puraido: Unmei no Shunkan (Pride: The Moment of Destiny), directed by Ito Shunya, pushed criticism of the ‘unjust’ Tokyo Tribunal to the fore. By arbitrarily invoking Justice Pal’s words and his Dissenting Opinion, the director presented a vision wherein Tōjō Hideki kept his pride. Fantasies and interpretations that distorted historical truth were featured in the movie, and it became influential in right-wing discourse in contemporary Japanese society along with the movement of the Japanese Society for History Textbook Reform. Pal also appeared in the comic book Sensō Ron (On War) by Kobayashi Yoshinori in the same year. In the cartoon, Pal’s argument was quoted as justifying Japan’s Greater East Asia War. For example, Kobayashi drew a balloon from Pal’s face, which said, ‘All defendants are not guilty!’ and included this commentary:

In the war / the United States / had absolutely no justice /

Japan / had justice / of self-defence / furthermore of protecting the whole of Asia from the Western powers!

Kobayashi in his 2008 manga Pāru Shinron (The True Arguments of Pal). In this manga, again distorted Justice Pal’s argument and criticised my book Justice Pal: Criticism of the Tokyo Trial and Absolute Pacifism as a prelude to falsely claiming that Justice Pal’s Opinion was that ‘Japan was not guilty’.

As explained, Justice Pal’s Opinion has been invoked in Japanese revisionist discourse to justify the Greater East Asia War and to discredit the Tokyo Tribunal. Pal’s position has been employed in attempts to lend legitimacy to Japanese historical revisionists in ways that distort Pal’s thinking, writing and intention.

The revisionists ignore the fact that Justice Pal criticized Japan’s invasions of Asia following the Manchurian Incident. They deliberately close their eyes to Pal’s severe condemnation of Japan’s war crimes. Furthermore, they do not mention Pal’s passionate call for the establishment of an international agency, unarmed neutrality, and his opposition to Japan’s remilitarisation, while distorting selected elements of Justice Pal’s Opinion to strengthen their claims.

It is important to free Justice Pal’s Dissenting Opinion from the false framework constructed by the right wing, and reexamine it in light of historical evidence. This effort will strengthen the analysis of the opponents of historical revisionism and the pervasive neonationalist tilt in contemporary Japan.

This is a revised version of a chapter from the book, Beyond Victor’s Justice; The Tokyo War Crimes Trial Revisited edited by Yuki Tanaka, Tim McCormack and Gerry Simpson and published with permission from Martinus Nijhoff Publishers.

Nakajima Takeshi is Associate Professor, Public Policy, Hokkaido University. He is the author of Pāru Hanji: Tōkyō Saiban hihan to zettai heiwa-shugi (Justice Pal: Criticism of the Tokyo Trial and Absolute Pacifism) and Bose of Nakamuraya: an Indian revolutionary in Japan.

Recommended citation: Nakajima Takeshi, ‘The Tokyo Tribunal, Justice Pal and the Revisionist Distortion of History,’ The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 9, Issue 44 No 3, October 31, 2011.

Articles on related subjects:

• Madoka Futamura, Japanese Societal Attitudes Towards the Tokyo Trial: A Contemorary Perspective

• Yuki Tanaka and Richard Falk, The Atomic Bombing, The Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal and the Shimoda Case: Lessons for Anti-Nuclear Legal Movements

• Cary Karacas, Fire Bombings and Forgotten Civilians: The Lawsuit Seeking Compensation for Victims of the Tokyo Air Raids

• Awaya Kentaro, The Tokyo Tribunal, War Responsibility and the Japanese People

• Terese Svoboda, U.S. Courts-Martial in Occupation Japan: Rape, Race, and Censorship

• William Underwood and Kang Jian, Japan’s Top Court Poised to Kill Lawsuits by Chinese War Victims

Notes

1 Translated by Kasahara Hikaru. Edited by Mark Selden.

2 Charter of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, signed in Tokyo on 19 January 1946, amended 26 April 1946, TIAS 1589, 4 Bevans 20 (‘Tokyo Charter’).

3 United States et al v Araki Sadao et al in The Tokyo Major War Crimes Trial: The Records of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, with an Authoritative Commentary and Comprehensive Guide (2002) Vol 105, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 36–7 (‘Tokyo Major War Crimes Trial’).

4 Ibid Vol 105, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 37 (emphasis in original).

5 Ibid Vol 105, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 45.

6 Ibid Vol 105, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 67.

7 Ibid Vol 105, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 15.

8 Ibid Vol 108, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 1069.

9 Ibid Vol 108, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 1099.

10 Ibid Vol 108, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 1069–70.

11 Ibid Vol 108, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 1089.

12 Ibid Vol 108, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 1111.

13 Ibid Vol 108, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 1171–2.

14 Ibid Vol 108, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 1180.

15 Ibid.

16 Ibid Vol 108, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 1172.

17 Ibid Vol 108, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 1180.

18 Ibid Vol 108, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 1090.

19 Ibid Vol 106, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 376.

20 Ibid Vol 106, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 428.

21 Ibid.

22 Ibid.

23 Ibid Vol 106, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 429–46, 460–2.

24 Ibid Vol 106, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 473.

25 Ibid Vol 106, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 513.

26 Ibid Vol 106, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 524.

27 Ibid Vol 106, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 525.

28 Ibid Vol 106, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 526.

29 Ibid Vol 106, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 527.

30 Arnold J Toynbee, Survey of International Affairs 1932 (1933) 465 quoted in Ibid Vol 106, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 527.

31 Ibid 467 quoted in Tokyo Major War Crimes Trial, above n 3, Vol 106, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 528.

32 Ibid Vol 106, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 524.

33 Ibid Vol 106, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 547(34)–(35).

34 Ibid Vol 106, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 548.

35 Ibid Vol 106, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 483 (emphases in original).

36 Ibid Vol 107, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 785(2)–(3) (emphases in original).

37 Ibid Vol 107, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 785(3).

38 Ibid Vol 107, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 785(20).

39 Ibid Vol 107, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 787.

40 Ibid Vol 107, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 785(29).

41 Ibid Vol 107, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 874–5.

42 ‘United States Note to Japan 26 November’ (1941) 5 Department of State Bulletin 461 (‘Hull Note’).

43 Tokyo Major War Crimes Trial, above n 3, Vol 107, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 978.

44 Ibid Vol 107, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 963.

45 Ibid Vol 108, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 1038–9.

46 Ibid Vol 108, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 983.

47 See, e.g., ibid Vol 106, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 446 .

48 Ibid Vol 108, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 988.

49 Ibid Vol 107, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 692.

50 Ibid Vol 107, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 736.

51 Ibid.

52 See, eg, ibid Vol 108, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 983, 988, 1234.

53 Ibid Vol 105, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 135 (emphasis omitted).

54 Ibid Vol 105, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 146.

55 Ibid Vol 105, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 55.

56 Chūgoku Shimbun (Hiroshima, Japan), 4 November 1952.

57 Tanaka Masaaki, Nihon muzairon: shinri no sabaki [On Japan’s Innocence: The Truth on Trial] (1952).

58 Ibid 28.

59 Tokyo Major War Crimes Trial, above n 3, Vol 108, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 988.

60 Ibid Vol 108, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 983.

61 Tanaka Masaaki, Pāru Hanji no Nippon Muzai-ron [Justice Pal’s Discussion of Japan as Not Guilty] (1963).

62 Tokyo Major War Crimes Trial, above n 3, Vol 108, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 1025.

63 Tanaka, Pāru Hanji, above n 61, 165.

64 Tokyo Major War Crimes Trial, above n 3, Vol 108, Dissenting Opinion of Justice Pal, 1089.

65 Hayashi Fusao, Dai Tōa sensō kōteiron [Affirming the Greater East Asia War] (2nd ed, 2006) 341.

66 Tanaka, Pāru Hanji, above n 61, 342.

67 Ienaga Saburo, ‘15-nen Sensō to Pāru Hanketsu-sho’ [The Fifteen Years’ War and Pal’s Dissentient Judgment] in Ienaga Saburo, Sensō to Kyōiku o Megutte [On War and Education] (1973) 23–43.