The Atomic Bomb and Hiroshima on the Silver Screen: Two New Documentaries

Robert Jacobs

Two valuable new documentaries on atomic weapons and their human legacy offer new light on the inner world of atomic testing and weapons manufacture and the impact of the bomb on atomic test areas in the United States, on Bikini, and Hiroshima.

Atomic Mom

M.T. Silvia’s directorial debut, Atomic Mom, is an ambitious, complex, and eminently successful film on many fronts.1 Silvia has made a film that is both historically compelling and deeply personal, a rare achievement. The focus of the film is the story of her mother, Pauline Silvia, a naval biologist who worked at the Rad Lab in San Francisco, and the evolution of the relationship of mother and daughter as M.T. explores her mother’s life and work. Pauline’s pathbreaking life is a compelling subject in its own right, but M.T. goes far beyond that to allow the viewer to come along as her exploration redefines the relationship between mother and daughter. Rich in archival footage on the making of the bomb, the film is even richer in its humanity.

|

The story begins with the young M.T.’s involvement in anti-nuclear protests in the 1980s and her founding of a group called the “Atomic Daughters.” The journey from her activism as an atomic daughter to a filmmaker focused on her “atomic mom,” and the reworking of the mother-daughter relationship that this entailed, provides the narrative arc of the film.

M.T. is the “atomic daughter” of Pauline, and M.T. describes how the secrets of her mom’s work on atomic weapons created a barrier between them. During a visit to M.T., Pauline brings a box of documents from these years and her story begins to open up to both her daughter and the audience. Pauline worked at the Rad Lab in San Francisco, which included time at the Nevada Test Site (NTS) north of Las Vegas, where she witnessed atmospheric tests in the early 1950s. Her work as a biologist focused on the effects of radiation on animals. This included lab work in San Francisco, and later involved preparing animals for direct exposures to nuclear detonations and subsequent analysis of the biological effects. Pauline describes her approach to her work at this time in clinical terms, a matter of gathering data on the effects of radiation. But as her story unfolds it is clear her experiences did indeed take a toll on her. She talks of being unable to stand the sound of a dog’s nails on a table at the veterinarians because it evoked memories of the struggles of the dogs in Nevada. Pauline adds that, “they were doing the same things to those men we were doing to the animals.” She wonders if they studied the men, saying, “that’s the piece that’s missing.”

Slowly through the film we see Pauline move through a process of reassessment of her work in the Navy, and a deepening bond between mother and daughter. M.T. facilitates Pauline’s meeting with fellow test site veteran Ray Harbert, an engineer who worked at the NTS and was also at the Pacific Proving Ground for the disastrous hydrogen bomb Bravo test at Bikini in 1954 that irradiated hundreds of Marshallese as well as the Japanese fisherman aboard The Lucky Dragon #5, and left several atolls uninhabitable. This making of community has obvious healing effects for Pauline, who has felt the burden of her secrecy oath throughout these 50 years as the oath is “for life.”

Several other striking pieces of the story unfold through the film. Pauline’s obvious strength as she raises two daughters as a single mother in the 1950s, her struggle to find a home for her Christian faith after she is unwelcome in the Catholic Church following her divorce, her visit to the Atomic Testing Museum in Las Vegas where she silently prays for forgiveness, and her support for M.T.’s ongoing antinuclear activism. The depth of M.T.’s respect and love for her mother emerges through her devotion to building a new and authentic bond with her that can be inclusive of the difficulties of their earlier relationship.

Atomic Mom expertly uses archival footage to evoke the tone of the early Cold War and the environs of the NTS, both its imperative for secrecy and the chaos of the testing itself. There is important historical content here as well as good filmmaking. Pauline shares a story of a veterinarian who worked in her lab at the NTS who “disappeared” for three days after a particular test. The vet returns with some very contaminated animals for study, and from Pauline’s tale it is clear that this was in response to the catastrophic Harry test of the Upshot-Knothole series (19 May 1953) which spread immense amounts of radioactive fallout throughout Southern Utah. The doctor recounts how large numbers of sheep and other animals were dead for miles around the town of St. George. What, the viewer wonders, were the effects on people. Pauline recounts how the vets’ superiors tried to get him to change his report to leave these details out. While much is known about this incident, the story of this veterinarian is new and of historical significance.

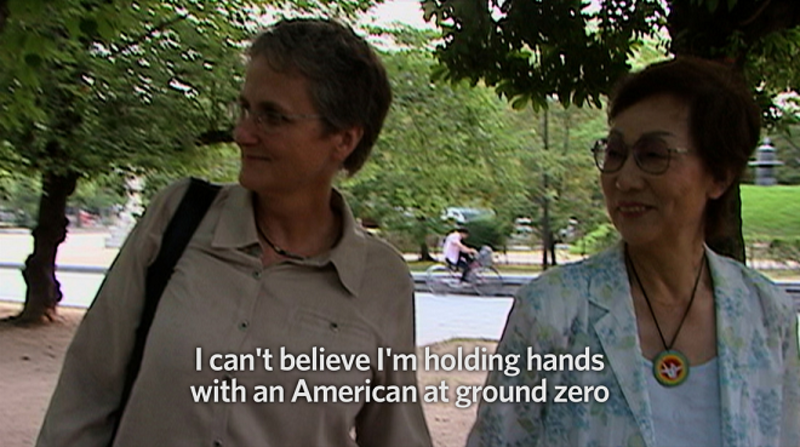

M.T.’s work takes her to Japan, and she makes a side trip to Hiroshima where she meets Okada Emiko, a hibakusha, and later her daughter Tominaga Yukie. Emiko shares the story of her experiences during the nuclear attack on Hiroshima, and M.T. and Emiko visit the Hiroshima Peace Park together. M.T. shares the story of her mother with Emiko who is moved by Pauline’s suffering. This juxtaposition of the hibakusha expressing her sympathy for the burdens of a scientist who worked at the test site is very powerful, and Emiko later makes some folded paper peace cranes for M.T. to bring back to her mother.

|

The power of this sharing between mothers across an ocean, and a historical divide, facilitates the healing that is the undercurrent of the whole film. Pauline is clearly deeply moved that Emiko has sent the paper cranes to express her feelings for Pauline. Though Pauline had nothing to do with the Manhattan Project or the attacks on Japan (she was a teenager at the time), it is obvious that her work on nuclear weapons has left her with a sense of guilt and responsibility. Emiko’s efforts help Pauline to release some of the distress that her work has caused her conscience over the years.

By introducing Emiko and Yukie, M.T. establishes a second mother/daughter relationship to mirror her relationship with Pauline, and as the film unfolds the healing of the relationship of M.T. and Pauline, it also moves us through the healing that comes from the bond established, at a distance and through M.T., of Pauline and Emiko.

|

M.T. began this work as a means to reconnect with her mother, and to heal what rift may have been between them, and inside Pauline herself, but ultimately the work becomes larger. A series of contrasting mirrors emerges in the film: that of the American mother/daughter and the Japanese mother/daughter, that of powerful but very different lives led by the Pauline and M.T. reflecting different historical moments, and even that of the animals and the human victims of deliberate radiation exposures. Through these contrasts we emerge at the end of the film both as witnesses to a process of healing, and feeling a little more whole ourselves. By accomplishing this, M.T. Silvia has made not a good, but a great film (trailer found here).

Witness to Hiroshima

|

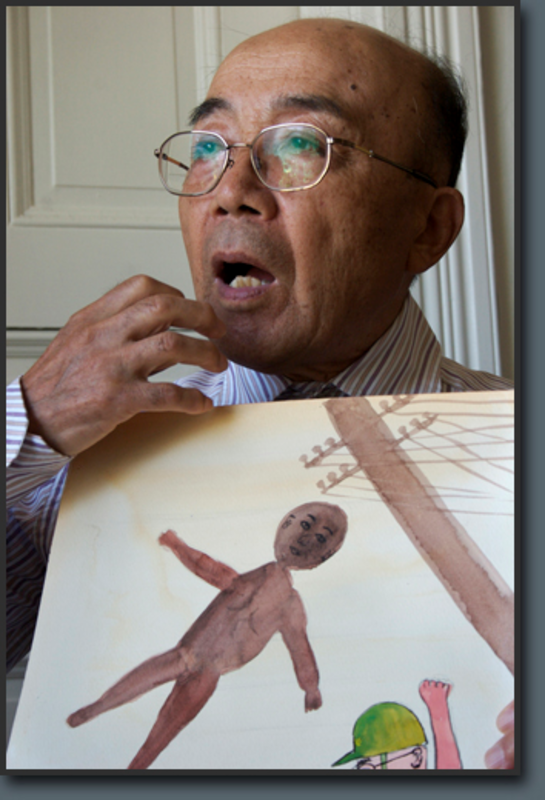

Kathy Sloane’s Witness to Hiroshima is a simple yet powerful film, which presents the testimony of a survivor of the Hiroshima nuclear attack telling his story, illustrated by 12 water color panels that he produced late in life.2 The most historically compelling aspect of Witness to Hiroshima centers on whose tale is being told. Tsuchiya Keiji does not tell the hibakusha’s tale that we are accustomed to hearing in such films, he was not, as are so many hibakusha today, a child sharing the tale of the fate of the family and the impact of the bombing on his or her life and health. Tsuchiya was a young Japanese soldier who witnessed the bombing from an island 13 km away in the Seto Inland Sea who was ordered, along with his fellow soldiers, to enter Hiroshima a few hours after the blast. His story is one seldom told, of the aftermath and the immediate clean up performed by military personnel. Tsuchiya recounts the horrors of stacking bodies of the wounded in a row only to find them all dead not long after, of clearing roads and performing mass cremations late at night. He describes soldiers pulling the bodies of the dead from the Ota River one by one, placing them in the fire and saluting as they were cremated, each having had a piece of cloth taken from their clothes for later identification purposes. He describes repeated incidents of the soldiers being doused with black rain which would irradiate them. He talks of a city full of desperate messages scrawled on any available surface from people desperately looking for family members, or leaving notes to family members about where they could be found.

|

The simple water color paintings that Tsuchiya has produced to illustrate his story form the backdrop to his tale in this 16 minute film. As in many hibakusha stories that employ paintings produced in later life to illustrate the tale, the simplicity of the paintings (as is typical, these are his first works of art) offers both easy access to his story, but also provides a jarring juxtaposition to the horrors of his tale. The paintings of corpses on bonfires serve to convey, not an accurate illustration of the scene itself, but rather the process of softening and normalizing the experience so that one can continue to live in spite of having endured such horrors. In this way the use of the paintings opens us up the process of psychological healing that has allowed Tsuchiya to carry on.

Moving past the horrifying stories of clearing and cleaning the devastated city of the corpses of people and animals, Tsuchiya talks of succumbing to radiation sickness a month later when he is demobilized, and his long journey back to health. He watches friends put their postwar lives together, of going to school and taking jobs, while battling his way back to health. He then goes on to become a junior high school science teacher and finds his life’s work. He is introduced by a scientist in his home near Okayama to the plight of the horseshoe crab, whose habitat was being decimated and was facing extinction. Tsuchiya became an expert on the horseshoe crab in the nearby Seto Sea and worked throughout his life to protect their habitat and to teach young and old, eventually opening the Kasaoka City Horseshoe Crab Museum, the only one of its kind in the world (link).

In his devotion to the horseshoe crab Tsuchiya is able to overcome the horrors of what he saw and endured in Hiroshima in August 1945 and to focus on life, growth and the future. Likewise, director Kathy Sloane is able to pack an astonishing amount of Tsuchiya’s life journey into a short film by letting the subject and his artwork speak for itself, an admirable directorial decision (video clip found here).

Robert Jacobs is an associate professor at the Hiroshima Peace Institute at Hiroshima City University. He is the author of The Dragon’s Tail: Americans Face the Atomic Age (University of Massachusetts Press, 2010) and the editor of Filling the Hole in the Nuclear Future: Art and Popular Culture Respond to the Bomb (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2010).

Information about Atomic Mom, and a trailer, is available here http://www.atomicmom.org/

Information about Witness to Hiroshima and a video track in English and Japanese is available here http://www.witnesstohiroshima.com/

Recommended citation: Robert Jacobs, ‘The Atomic Bomb and Hiroshima on the Silver Screen: Two New Documentaries,’ The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 9, Issue 42 No 3, October 17, 2011.

Articles on related topics

• Kyoko Selden, Memories of Hiroshima and Nagasaki: Messages from Hibakusha: An Introduction

• Ōishi Matashichi and Richard Falk, The Day the Sun Rose in the West. Bikini, the Lucky Dragon and I

• Robert Jacobs, Whole Earth or No Earth: The Origin of the Whole Earth Icon in the Ashes of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

• Robert Jacobs, 24 Hours After Hiroshima: National Geographic Channel Takes Up the Bomb

• Nakazawa Keiji, Hiroshima: The Autobiography of Barefoot Gen

• Nakazawa Keiji interviewed by Asai Motofumi, Barefoot Gen, the Atomic Bomb and I: The Hiroshima Legacy

• John W. Dower, Ground Zero 1945: Pictures by Atomic Bomb Survivors

Notes