Capital Punishment without Capital Trials in Japan’s Lay Judge System

David T. Johnson

I really agonized. I cried many times during the trial, and now when I recall it I still shed tears. I want you to understand this.

Man in his fifties who served on the first lay judge panel that imposed a death sentence in Japan (press conference after the trial of Ikeda Hiroyuki, November 16, 2010)

Does capital punishment do justice? We the people who constitute society have entered an era in which we must directly confront the death penalty and answer this question.

Tokyo Shimbun (November 17, 2010, p.26)

In May 2009, Japan began a new trial system in which ordinary citizens sit with professional judges in order to adjudicate guilt and determine sentence in serious criminal cases.1 This change injected a meaningful dose of lay participation into Japanese criminal trials for the first time since 1943, when Japan’s original Jury Law was suspended during the Pacific War. In May 2010, newspapers reported that the new system “has had a smooth first year,”2 though they also stressed that it “has yet to be really tested by cases involving complex chains of evidence or demands by prosecutors for the death sentence.”3

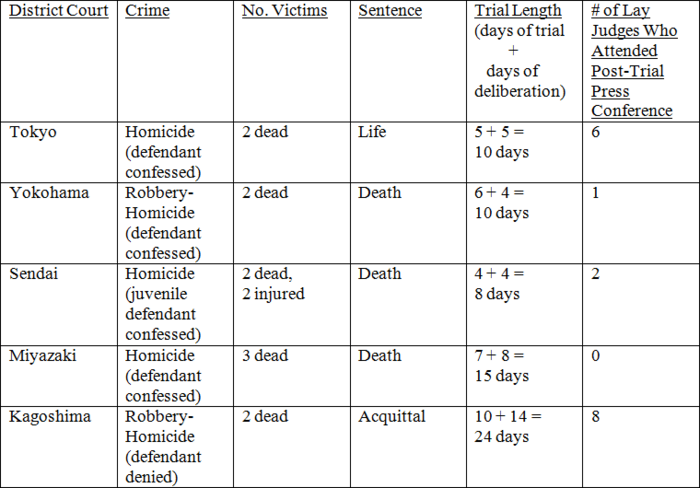

The new system is being tested in its second year. In June-July 2010, lay judge panels handed down three complete or partial acquittals in cases involving complex evidence and defendants who denied guilt, causing some prosecutors to contend that the new system makes it “harder and harder to persuade lay judges that defendants are guilty”—despite the fact that these not-guilty verdicts were the first that lay judges had rendered in more than 600 trials.4 In September, a lay judge panel in Tokyo evaluated the contradictory claims of medical experts and endured two weeks of frenzied media coverage before convicting actor Oshio Manabu and sentencing him to two-and-one-half years in prison for failing to call an ambulance to aid Tanaka Kaori, who died of an overdose of Ecstasy (MDMA) that Oshio had given her when they met to have sex in a Roppongi apartment (prosecutors wanted a six-year sentence).5 And in October, Japanese citizens started to decide who the state should kill. By the end of 2010, lay judge panels had made five capital decisions, resulting in one life sentence, three death sentences, and one acquittal. See Table 1.

Table 1. Capital Trials in Japan’s Lay Judge System, 2010

Sources: Yomiuri Shimbun, “Kensatsugawa ga Shikei Kyukei Shita Saibanin Saiban no Hanketsu,” December 11, 2010, p.24, and other newspapers.

Note: The number of “days of deliberation” reflects the number of days scheduled. In some cases, the actual number of days deliberated is less than the scheduled number.

This article describes the first two “capital trials” in Japan’s lay judge system and explores a few of the salient issues that are raised when citizens make life-and-death decisions. It also summarizes the other “capital trials” of 2010. One key finding is that while Japan has capital punishment, it does not have anything that can be called a “capital trial” because until the penultimate trial session, when prosecutors make their sentencing request, nobody knows whether the punishment sought is death or something less. The rest of this article omits the quotation marks that were used in the previous three sentences to call attention to this troubling fact.

A Life Sentence for Hayashi Koji

“I did something really terrible. When I see the victims’ photographs and their bereaved family members in court, I once again feel deep regret over what I have done. Perhaps there is nothing to be done except atone for my crimes by giving up my own life, though sometimes I feel this might be running away. Perhaps it is better to atone by living and remembering. I am deeply sorry for what I have done, and I have no excuses.”

Defendant Hayashi Koji’s final statement to the court before it deliberated about his sentence. He spoke these words through tears, and concluded with a ninety-degree bow that he held for several seconds (Tokyo District Court, October 25, 2010)

In countries like Japan and the United States which retain the death penalty, capital trials are one of the most suspenseful criminal justice rituals, not least because the moment of sentencing is saturated with emotion and uncertainty.6 Juries in the United States and lay judge panels in Japan have virtually untrammeled power to choose between life and death. In both countries, capital decisions ultimately “rest not on a legal but an ethical judgment—an assessment of the ‘moral guilt’ of the defendant” (former U.S. Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens, in Spaziano v. Florida, 1984).7

In Japan’s first capital trial, Hayashi Koji, age 42, was sentenced to life in prison for murdering two women on August 3, 2009. One of his victims was 78-year-old Suzuki Yoshie, whom Hayashi smashed in the head with a hammer five or six times before stabbing her in the upper body 16 times more. Suzuki had surprised him when he broke into her house at 9:00 on that Monday morning.

Hayashi’s second victim and main target was Suzuki’s 21-year-old granddaughter, Ejiri Miho, whom Hayashi had patronized at an “ear-cleaning salon” 154 times in the previous 14 months, and whom he stabbed in the neck five or six times soon after he had killed Suzuki. Ejiri died from the wounds one month later. Hayashi felt unrequited love for Ejiri—or lust, or longing, or something—and he was angry that the management of her shop had forbidden him to visit any more.

Hayashi was arrested while washing the blood off his hands in the kitchen of the house where these murders occurred—an impossible task because he had cut his own hand during the killings. Before committing the crimes, Hayashi had been a reliable company worker for some 20 years and possessed over $100,000 in savings. But his bank account was rapidly diminishing, for an hour of Ejiri’s time cost $60, and on Saturdays and Sundays he sometimes spent up to seven hours enjoying her services. The parties to the case agree that those services were non-sexual. Ejiri cleaned Hayashi’s ears, at least occasionally, but most of their time together was spent talking, holding hands, watching DVDs, and eating food that Hayashi had purchased on his way to the salon. According to Hayashi, when he failed to bring the foods that Ejiri had requested, she scolded him, which sometimes brought him to tears.

As this description suggests, Hayashi does not cut a very macho image. At five feet, six inches tall (169 centimeters), he weighed 101 pounds (46 kilograms) at the time of his trial, down nearly 40 pounds (18 kilograms) from what he weighed when he was arrested 14 months before. Hayashi has never been married and (he testified) never had a serious girlfriend. Since the age of 26 he has suffered from a severe form of arthritis which requires medical treatment. He has lived on his own for about the same period of time, having left his home in Chiba when his father ordered him out. At trial, Hayashi’s mother described the father as an “extremely selfish and self-centered” man who “angers easily,” but said she knew of no instance in which the father had physically abused her son.

In addition to their regular meetings at the salon—11 times per month, on the average—Hayashi and Ejiri traded emails and exchanged gifts on birthdays, Christmas, and Valentine’s Day. According to Hayashi, Ejiri urged him to visit the salon more often, at least until a month or two before she was murdered, when Hayashi’s attentions apparently crossed the line that separates welcome interest from stalking.

By all accounts Ejiri was good at her job, with monthly earnings that sometimes exceeded 650,000 yen ($8000)—a little more than what Hayashi earned for working 45 to 50 hours a week in his company. Ejiri’s boss testified that she was the top-earning ear-cleaner out of more than 100 who worked at the salon. The desire not to cut into her income or his own profits may help explain—in part—why the boss waited a long time to respond to Ejiri’s concerns about Hayashi, whom she sometimes saw hanging around places he knew she would be. It remains unclear even after the trial why neither Ejiri nor her boss complained to the police about behavior prosecutors described as “persistent stalking.”

Hayashi had no prior arrests, he frequently wrote letters of apology and remorse to the surviving family members of the victims, and he did not dispute any of the core claims in the prosecution’s case except for their characterization of his relationship with Ejiri as a one-way emotional street. As the opening epigraph of this section recounts, Hayashi even told the court he was unsure whether he should atone for the murders by living or dying. In murder cases in Japan, defense lawyers often coach and encourage their clients to show remorse and regret, by writing letters of apology to the bereaved, reading books that victims have written, and otherwise playing the penitent role. Some Japanese lawyers are troubled by this kind of defense counseling. As one of them wonders:

“Can the criminal process change a defendant’s personality? Can finders of fact discern whether the defendant’s expressions of remorse are genuine? And do defense attorneys have moral grounds to try to change their client’s behavior? Regardless of how you answer these questions, this practice [of defense lawyers counseling their clients] will continue because Japanese criminal law gives vast sentencing discretion to the court and because Japanese media love to tell emotional stories about ‘life and death decisions.’”8

This, then, was a sentencing trial, with the defendant’s remorse conspicuously on display. Yet nobody knew what sentence prosecutors would request until the final day before deliberations. The selection of lay judges occurred on October 18 and lasted for about two hours, while the trial itself took five days, with an additional four days of deliberations before sentencing occurred on November 1. The trial thus took two weeks to complete, with each trial session beginning at 10:00 or 10:30 AM and lasting until 4:30 or 5:00 PM, with 90 minutes off for lunch and one break in the morning and two more in the afternoon. On the average, court was in session four to five hours per day.

Unlike jury selection for capital cases in the United States, which is a long and complicated process, the selection of lay judges in Japan is fast and mechanical—and so it was in Hayashi’s case. In interviews with the author, one of the trial prosecutors would not say whether he used any of his rights to excuse potential jurors without cause (in this case, each litigant could use up to six challenges, but the prosecutor said information about how they are used is confidential), while one of Hayashi’s three defense attorneys said he and his colleagues had excused a few women they deemed likely to sympathize with the female victims. The defense lawyer stressed, however, that this was a guessing game, because the parties to the case knew nothing about prospective lay judges except their names, addresses, and (sometimes) general employment status, and because the chief judge neither pursued nor encouraged any significant lines of questioning concerning the life experiences and potential prejudices of the people who would be asked to make a life or death decision.9

Since guilt was not contested, the main focus of the trial was assessing the defendant’s culpability. For that purpose, the prosecution and the defense both relied on the so-called “Nagayama standards,” which the Supreme Court articulated in 1983 as guidelines for deciding who deserves death. There are nine: (1) the character of the crime, (2) the defendant’s motive, (3) the crime situation (cruelty and heinousness), (4) the importance of the result (especially the number of victims), (5) the feelings of the victims and survivors, (6) the social effects of the crime, (7) the age of the defendant, (8) his or her prior record, and (9) the circumstances after the crime (such as whether the defendant repents and apologizes). According to the Supreme Court, a death sentence should be imposed only if, all factors considered, “it is unavoidable” and “cannot be helped” (yamu o enai). Decision-makers are also supposed to consider questions of deterrence and proportionality.10

The Nagayama factors are an impossibly vague grab bag of criteria for structuring life-and-death decision-making. As one defense lawyer says, “they are not standards (kijun), they are simply talking points” (hanashite mo ii tokoro). The punch line—that death is the appropriate sentence when it is “unavoidable”—simultaneously denies the reality of choice in capital decision-making, fails to provide guidance about how to weigh the various factors, and begs the question of when death should be chosen instead of life.11

|

Nagayama Norio |

But the Nagayama factors do form a much simpler scheme for capital sentencing than the complex guidelines that have grown up around the many opinions issued by the U.S. Supreme Court since the death penalty was reinstated in America through a 1976 decision (Gregg v Georgia) which held (in an ambivalent double-negative) that “the death penalty is not a form of punishment that may never be imposed.” Japan’s present approach to capital sentencing unwittingly reflects nothing so much as the conclusion enunciated by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1971, when it concluded that the rights of a defendant are not infringed by imposition of a death penalty without governing standards. As Justice John Harlan observed in that case, “To identify before the fact those characteristics of criminal homicides and their perpetrators which call for the death penalty, and to express these characteristics in language which can be fairly understood and applied by the sentencing authority, appear to be tasks which are beyond present human ability” (McGautha v California, 402 U.S. 183, p.204). The year after McGautha was decided, its “beyond human ability” holding was repudiated by Furman v Georgia (1972), which determined that sentencing discretion must be narrowed “so as to minimize the risk of wholly arbitrary and capricious action.” Japan has never had a Furman-like decision, and many legal professionals—including the senior defense lawyer and the lead prosecutor in Hayashi’s case—believe the current framework for capital sentencing is seriously deficient.12

Whatever the problems in the Nagayama scheme, all the parties in Hayashi’s case felt the need to discuss its factors, and the court ultimately framed its decision—a life sentence for Hayashi—in those terms. The following table summarizes the main claims each side made and the court’s ultimate findings.

Table 2. Sentencing Factors in Hayashi Koji’s Murder Trial, Tokyo District Court

Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, November 2, 2010, p.11.

As summarized in the first row of Table 2, the Nagayama factors include the feelings of the victims and the bereaved. About the same time that Japan’s lay judge system started, a system of victim participation was implemented, expanding the rights and protections of victims and survivors, and giving them the right to make sentencing requests at trial. In Hayashi’s trial, the prosecution presented statements from four surviving family members, all of whom demanded a sentence of death. Two of those statements were read into the record by the prosecution, and the other two were read by the survivors themselves. The next few paragraphs summarize what the latter two said.

Suzuki’s eldest son cried intermittently while reading his five-page statement to the court. He called his deceased mother a “supermom” (supa-kachan) who had many friends and who loved nature and karaoke, and he said that while the defendant may regret getting caught for the killings, he feels no real remorse. This middle-aged man—probably in his mid-to-late fifties—also rebuked the defendant for testifying in court that Ejiri Miho sometimes talked smack about her colleagues and customers. “Cut the crap!” (fuzakeru na), Suzuki’s son raged at the defendant. “She would not do something like that!” The son concluded his statement by asserting—three times—that he wants the defendant sentenced to death, and by imploring the judges and lay judges to study the photos of his mother’s bloody body during their deliberations.

The other survivor who testified in person was the deceased Grandmother Suzuki’s youngest sister, who seemed to be in her sixties. She started by announcing that she hates the defendant because his crime is “so horrible and evil,” and the longer she spoke the more momentum she gained. She, too, wept while reading her statement, and sometimes she interjected how “vexed” (kuyashii) she felt by what the defendant had done. Suzuki’s sister also rebuked the defendant for trying to “trick” the court in his testimony. “You merely said what was convenient for you,” she insisted. “Give us the lives of our loved ones back!” Towards the end of her statement this woman broke into huge, gasping sobs, and when it became apparent she could not continue, her attorney stepped forward to finish reading it.13 The final words were as follows:

“I went to visit Yoshie’s grave the other day, and I told her that the next time I come I will definitely bring news of a death sentence (shikei hanketsu o kanarazu moratte kuru kara ne). My beloved sister is watching this trial, and I really want the court to give us a death sentence. I desire a death sentence. I hope you will do as I request.”

Ten days later, after the court returned without the sentence that this woman had promised her dead sister, she was escorted from the courtroom wailing that a life sentence was “good for nothing” and that she had been vexed and victimized again by a sentence that “makes no sense.”

As these examples suggest, one of the most striking aspects of Hayashi’s trial was its emotional intensity. I have never attended a trial in which so many people cried so often. The survivors wept when they testified and while observing the proceedings. Spectators wept. The lead prosecutor cried when he referred to the suffering of the survivors. A defense attorney cried while listening to the statements of the bereaved. The defendant frequently cried in court, and when he was not weeping his body was slumped in a posture suggesting shame and anguish. The defendant’s mother cried while reading her statement to the court. “I learned about these crimes while watching TV,” she said, “and when I visited my son in jail I could not even talk with him because he was sobbing so hard.” The mother also asked the court for permission to apologize to the survivors. When it was granted, she turned to face them and the rest of the spectators and said—while bowing 90 degrees and sobbing uncontrollably—“I am extremely sorry for what my son has done and for what you have had to go through” (this was when I wiped away tears). I noticed one of the three professional judges crying as she said this; he may have wept during other testimony too. Most conspicuously, at least four lay judges cried during the trial—and two wept openly and often.14

It is difficult to discern the proper role of emotion in a criminal trial. On the one hand, the U.S. Supreme Court has held that “it is of vital importance to the defendant and to the community that any decision to impose the death sentence be, and appear to be, based on reason” (Justice John Paul Stevens, in Gardner v. Florida (1977)). This is not merely an American sensibility.15 More broadly, one theme of American capital jurisprudence since the 1970s has been the effort to “rationalize” the sentencing process, which involves, in part, the substitution of rational principles and rule-of-law values for punitive passions and unguided jury discretion.16 On the other hand, the same U.S. Supreme Court that trumpets the importance of “rational” decision-making also permits the state to present “victim impact” evidence in the penalty phase of capital trials, although victims in America may not make specific sentencing requests as they are allowed to do in Japan (Payne v. Tennessee, 1991). As one analyst has observed, “it is hard to imagine an opinion that runs more directly contrary to the Court’s rationalizing reforms.”17

Some theorists of punishment believe that modern societies have sacrificed too much by turning their backs on values like honor and revenge that animated justice in pre-modern times. On this view, societies such as the United States and Japan could benefit from taking a close look at “talionic” societies that respected the impulse to exact revenge and made little distinction between revenge and justice.18 But revenge can be a dangerous emotion, not least to the person who feeds it. As Confucius observed 25 centuries ago, “Before you embark on a journey of revenge, dig two graves.”

No matter how one answers the normative question about the proper role of emotion in Japanese capital sentencing, the empirical reality is that victims now have substantial voice and influence in trials such as Hayashi’s—much more than they had five or ten years ago. One question is whether this constitutes progress, regress, or both. In making that determination, readers may want to consider three facts about Japan’s victims’ rights movement.

First, in murder trials such as this one, victims and survivors take on a kind of sacred status, and it becomes virtually impossible to cross-examine them or challenge their core claims—however emotional they may be. If cross-examination is one of the best engines ever designed for determining the truth (as an Anglo-aphorism insists), then the inability to use it must be deemed a significant sacrifice. In a murder trial I watched before Hayashi’s started—one in which the prosecution did not seek a sentence of death—the victim’s mother testified through tears about how badly she missed her daughter, even though (the defense lawyer knew) the two had been on bad terms for years before the crime, and even though the mother collected a tidy life insurance sum after the death of her daughter. The defense lawyer—one of Japan’s finest—told me that he remained silent about this issue for fear of creating the impression that he would be seen as “re-victimizing” a victim. Silences such as this were conspicuous at Hayashi’s trial too. In Japanese murder trials, some things cannot be said.19

Second, many supporters of capital punishment believe death sentences and executions give victims “closure” (kugiri ga tsuku). But the truth is more complicated, for the existence of capital punishment creates resentment among the many victims and survivors whose cases are not deemed capital. Japanese prosecutors seek a sentence of death in only a small fraction of murder cases—in 2009, about one in every 200.20 If the severity of sentence is deemed to reflect how much a victim is valued, then the infrequent pursuit of capital punishment encourages the perception that the vast majority of homicide victims are not adequately respected. To prevent this perception, prosecutors would need to start seeking capital sanctions at levels not seen since the Tokugawa era. Even the most ardent supporters of capital punishment do not want to go back to that future. More broadly, when the death penalty is framed as a matter of satisfying victims and helping them to achieve closure—as is often the case in Japan and the United States—one important effect is to legitimate a sanction that has become increasingly difficult to justify on other grounds. It is no coincidence that the acceleration of “serving victims” rhetoric corresponded with death penalty increases in Japan after 2000 and in the United States a decade earlier.21 To “privatize” capital punishment by framing it as a matter of meeting victims’ needs is to insulate the sanction from scrutiny and criticism it would otherwise receive.22

This connects to a third concern about victims in Japan’s capital process. Under present law, victims’ families are allowed and even encouraged to beg and compete for death penalty outcomes. The evidence summarized in this article suggests they do so willingly. But lobbying by victims and on their behalf conflicts with the core Nagayama claim that capital punishment should be imposed only when death is “unavoidable.” If it is the lay judges’ sense of necessity that is supposed to rule rather than that of the victims’ relatives, then invitations to the bereaved to plead for a death sentence both distort the capital sentencing process and influence prosecutors’ decisions about whether to seek a death sentence in the first place.

I have focused on one Nagayama factor—the feelings of the bereaved—because in many ways it is the most sociologically significant aspect of Hayashi’s trial. Yet despite the strong demands of the survivors for a sentence of death, the court ultimately sentenced Hayashi to life in prison, which in Japan means he will probably serve at least 30 years before becoming a viable candidate for parole.23 Some observers believe prosecutors pushed the “suffering survivors” theme too hard, and that it backfired,24 but at least three other factors seemed to influence the court’s decision. First, the court held that Hayashi’s year-long relationship with Miho Ejiri shaped his behavior. On this view, he became confused and upset when he was refused entry to the salon, and that mitigates his culpability. Second, while Hayashi intended to kill Ejiri, his attack on Suzuki was “unexpected” (guhatsu teki). In an awful sense, the grandmother was in the wrong place at the wrong time. Third, the court found that Hayashi has shown—“in his own way”—sorrow and remorse for his crimes, while also noting that he has no prior record. All things considered, this panel of nine persons concluded, it is better for Hayashi to spend the rest of his days—“until the last moment of his life”—continuing to “reflect on the personal deficiencies that caused him to commit these horrible crimes” and “continuing to anguish over what he has done while deepening his remorse for it.”25

On the day after this decision, Japanese newspapers focused on the statements lay judges made after trial. Four lay judges (two men and two women) and two alternates (both men) attended a post-trial press conference (two lay judges, both women, did not attend), and while they were prohibited by law from commenting on specific aspects of the case,26 they did make some interesting comments. An Asahi headline on page one said “Lay Judge: ‘I Placed Importance on My Own Feelings.’” As the accompanying article made clear, a longer headline would have read “…and Not on Law or Precedent.” In fuller form, here are the remarks of the male, thirty-something company employee to whom this headline refers:

“In the final analysis I stressed my own feelings about this case. I think the Nagayama standards were created for trials by professional judges. If I did not include my own thoughts about how to judge the case, there would be no point in even having lay judge trials. So this is how I decided.”

The other theme stressed by the mass media was the heavy “burden” (futan) that capital trials place on the citizens who serve as lay judges—a topic I discuss in more detail in the conclusion of this article. While the “burden” concern is partly a media construction,27 it also reflects widespread feelings in Japanese society and among lay judges who have served. One of Hayashi’s citizen judges said that “I even saw the evidence in my dreams, and when I showered before bed I shut my eyes and thought deeply about the case.” Another said, “I gradually felt the pressure of this case accumulate over time. The longer the trial lasted, the more I felt a feeling of responsibility for the outcome.” A third said, “This was a big case, and we did it with an extremely heavy sense of responsibility. To tell you the truth, my number one feeling is that doing this was really hard.” And a lay judge alternate said, “Japan has a death penalty system, and during this trial I thought deeply and anew about what the meaning of this punishment is.”

Thurgood Marshall, a former Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, once asserted that the more you know about capital punishment, the less you like it. Academic efforts to test the “Marshall hypothesis” have reached mixed conclusions, but the Hayashi trial makes me wonder whether there might be a corollary for Japan, especially when the secrecy that surrounds capital punishment prevents the public from pondering the issue.28 For Japanese lay judges, perhaps, the more you think about capital punishment, the less you like it?

A recent survey on capital punishment in Japan revealed that 85 percent of adults support the institution—about five persons in every six. If this percentage applies to the citizens who judged Hayashi Koji—and we cannot tell if it does—then their decision not to sentence him to death may lend support to the Marshall corollary.29 For one thing—and by their own admission—the citizens who served as lay judges were forced to think more deeply about capital punishment than they ever had before. For another, they did not have to be bloodthirsty bastards to conclude that Hayashi deserves death; all they needed to do is believe in the propriety of capital punishment and be willing to say (per Nagayama) that “all things considered” these were capital crimes. Hayashi Koji slaughtered two innocent women: one very old and one quite young. The surviving family members want Hayashi hanged. The defense contested none of the prosecution’s core claims, and the defendant himself wondered whether it might be best for him to atone for his “terrible offenses” by dying. In these ways and more, this was a powerful case for capital punishment. Yet the court chose life, and prosecutors did not appeal despite continued lobbying from the victims’ family.30 Japan’s second capital lay judge trial would reach a different conclusion.

A Death Sentence for Ikeda Hiroyuki

If you do not sentence the defendant to death in this case, then one has to wonder whether anyone in this country will ever receive a death sentence again.

Prosecutor’s closing argument in the capital trial of Ikeda Hiroyuki (November 10, 2010)31

I expect nothing less than a death sentence. I’m scared, but I think I have to accept it. I should not struggle before dying. My victims didn’t…But I’m not sure. Is it best to atone by living or dying?

Ikeda Hiroyuki’s trial testimony (November 4, 2010)

If you want to commit murder and stay off death row in a country where the clearance rate for homicide is 95 percent, it is best to leave your electric saw in the closet. This, anyway, seems to be one of the lessons from Japan’s second capital trial.

In Japan, when you use an electric saw to cut off a person’s head, and when you do it while that person is still alive and begging to be killed before being decapitated, then you may very well receive a sentence of death, especially if you killed another person beforehand by repeatedly stabbing him in the neck while the saw victim watched in the bathroom of the hotel room where you have imprisoned them. It will not help the cause of your own survival if you rob one of the victims of $150,000 before killing him, or cut the victims’ bodies into pieces so that you can dispose of them in the mountains and oceans of the surrounding region. Nor will it mitigate your guilt if you tell the court that murder is no worse than fraud. A police officer who investigated the killer who said and did these things stated that he “cannot remember such a horrible case,” while the prosecutor who sought a death sentence said that “of all the methods of killing that can be imagined, this one is the worst. This is an act so brutal one can barely conceive it was committed by a human being.”

For the first few days of his trial, 32-year-old Ikeda Hiroyuki seemed not to appreciate the gravity of the reality described in the preceding paragraph. When the prosecutor asked him what he thought as he listened to the victims begging for their lives, Ikeda said “I didn’t think anything at all.” When asked whether the beheading was cruel, Ikeda said “Well, I suppose if there is a proper way to kill a person, then my method may have been mistaken.” When asked to reflect on the seriousness of his crimes, Ikeda said “I don’t know which is worse: fraud, smuggling drugs, or murder. It is a difficult judgment to make.” And when he was asked to describe how the slaughters were performed, Ikeda spoke in great and gruesome detail, saying the bathroom was like “a sea of blood” and cutting up the bodies like “dismembering a crab.” Ikeda apparently came across the dismemberment method by watching American Gangster (2007), a Hollywood film starring Denzel Washington as a heroin-smuggling gangster, and Russell Crowe as the New York detective who pursues him. The gangster’s life ends badly in the film, a point the prosecutor pressed when he questioned Ikeda in court.

While Ikeda’s crimes certainly qualify as among the worst of the worst, some observers believe he experienced a conversion during trial. The only lay judge who attended the post-trial press conference—a man in his fifties—said that when the trial started Ikeda had an extremely defiant attitude, as if to say “Yeah, I did something bad, so go ahead and kill me.” But this lay judge also observed that as the trial progressed—especially after Ikeda heard the bereaved express their grief and anguish—he “saw the defendant’s eyes turn red [with tears]” and he “really understood that the defendant’s feelings had changed.”32 A newspaper reporter who attended the trial also stressed Ikeda’s attitudinal transformation, in addition to a change in his own assessment of what punishment the defendant deserves. When the trial started this reporter believed that Ikeda “absolutely” would and should receive a sentence of death, because the method of killing was so monstrous and the killer so remorseless. But as the trial proceeded the reporter felt hesitation about imposing the ultimate sanction, and he wondered if some lay judges might be feeling similar ambivalence. “The more I learned about the case,” this journalist reported, “the more I thought that death is the only appropriate sanction, and yet the more I learned about the defendant, the more I waivered about what punishment to choose.”33

Like Hayashi in the first capital trial, Ikeda did not dispute any of the prosecution’s core claims, and he repeatedly stressed that he would accept whatever sentence the court deemed appropriate, including death.34 Before trial Ikeda told his defense lawyer (Aoki Takashi) “I will get a death sentence and I don’t want defense representation.” After being sentenced to death, he bowed to the court and said “thank you very much” before turning and bowing to the trial observers (including ten or so bereaved family members and friends) and saying “I am extremely sorry for what I have done. I have no excuses at all.”

Because Ikeda has few excuses, it is all the more interesting that his lay judge panel apparently had a difficult time deciding what punishment he deserves. He was raised in a middle-class home without the deprivations of poverty or violence that tend to afflict persons who get condemned to death. He played tennis on his school teams. In junior high he was elected president of his class. He had no prior convictions, though he had been arrested (some years earlier he had joined, then quit, a yakuza gang). And he was married to a woman whose statement was read at trial. It said that if Ikeda receives a sentence that enables him to leave prison one day, she would be willing to wait. On hearing this statement, Ikeda insisted that it be withdrawn from the record because it was worded to favor his own interests (the couple was actually going through a divorce). In his view, that did not seem fair to the victims or the bereaved.

Ikeda’s co-offender in this case is said to be 26-year-old Kondo Takero, who used to be a student at elite Waseda University. Kondo fled after the crime, and as of this writing the police have not found him. He used to manage a mah-jongg parlor in Kabukicho—Tokyo’s largest red light district—where the two victims worked until they were kidnapped and killed. Kondo apparently got into an argument with them over how the parlor should be managed, and then he asked Ikeda to help him settle the score. According to trial testimony, Kondo wanted the first victim (age 36) killed, and Ikeda was delighted to do the dirty work. Ikeda himself suggested killing the second victim (age 28) in order to prevent him from complaining to the police.35 Early in 2009, Kondo had asked Ikeda to help him smuggle methamphetamine drugs, which Ikeda likened to “being chosen by God.” When Ikeda was subsequently asked to assist in more violent ways, he said he wanted to prove that “I am a person who can kill” in order to gain more of Kondo’s trust and thereby more of the money that comes from smuggling drugs.

In order to reduce the “burden” on lay judges, Ikeda was tried by two separate panels. In the first trial, which lasted three days, he was found guilty of smuggling methamphetamines and of assaulting a police officer in the jail where he was incarcerated before trial. In the second, which took six days to try and three days to deliberate, Ikeda was found guilty of robbery-homicide and sentenced to death. The same three professional judges sat at both trials, but the lay judges differed, and only the second panel made any decision about punishment.

Before the capital trial, 180 citizens were asked to attend the session where lay judges would be selected, of whom 108 (60 percent) received permission not to come (Japan’s lay judge law recognizes a wide variety of excused absences). Of the 70 or so citizens who did attend, 12 were selected: the 6 who ultimately judged Ikeda, and 6 more who served as alternates (the legally permitted maximum). During the selection process, no one was asked any questions about capital punishment. As in Hayashi’s case and the vast majority of other lay judge trials in Japan, the process was fast and mechanical.

Prosecutors organized their case around the Nagayama factors, and Table 3 summarizes their main claims. In effect, prosecutors tried to persuade the court to answer two questions in the affirmative: Do you loathe the defendant? And do you fear him? Towards that end, they focused on the character of the crime and the defendant’s motive, the method of killing, the importance of the result (two dead men), and the feelings of the bereaved. Four survivors testified at trial and another had a statement read into the record. All demanded death.

Table 3. Sentencing Factors in Ikeda Hiroyuki’s Murder Trial, Yokohama District Court

Source: Mainichi Shimbun, November 17, 2010, p.3.

One survivor who rebuked Ikeda for “throwing away the victims’ bodies like garbage” called him “the most abominable person in the world.” Another implored the defendant to go fetch her son’s broken body from Yokohama harbor. A third lamented that Ikeda will leave the planet in one piece—and without much suffering. Compared to what he put the victims through, “this would be a blessed way to die!” Ikeda’s trial—like Hayashi’s—was saturated with sadness, anger, hatred, and the desire for revenge. It was also awash with tears, from lay and professional judges, spectators, attorneys, mothers, the fiancé of the youngest victim and the wife of the eldest, the defendant, his wife, and, above all, bereaved family members and friends.

In response to the emotionally powerful appeals made by prosecutors and survivors, the defense rested on five main claims:

1. The leader of these crimes was the absent Kondo, not Ikeda.

2. Ikeda confessed to the homicides soon after being arrested for smuggling drugs.

3. Ikeda’s cooperation helped reveal the truth of the murders.

4. Ikeda can be rehabilitated.

5. The Nagayama decision counsels that if there is any hesitation about imposing a sentence of death, then a lesser sentence should be given.

In the decade or so before Ikeda was charged with these murders, Japanese prosecutors sought a sentence of death for at least eight defendants who were charged with killing two people and subsequently tried by professional judges. Trial courts imposed a sentence of death on three of the eight, and these condemned men had two things in common: their murders were premeditated, and they were carried out for pecuniary gain. Ikeda’s death sentence fits this pattern. That, and the breathtaking barbarity of his behavior, helps explain why most commentators concluded that this lay judge panel reached the same conclusion a panel of three professional judges would have reached if the trial had taken place before lay judge trials started.36

In some ways, reactions after Ikeda was sentenced to death echoed those that followed Hayashi’s life sentence. In particular, the media worried greatly about the heavy “burden” lay judges feel in capital trials, and some even called for the removal of life-and-death decision-making from the jurisdiction of lay judge trials. My own conversations with Japanese citizens suggest that this concern is shared by many members of the public. As the opening epigraph of this article suggests—“I cried many times during trial, and now when I recall it I still shed tears”—the sole lay judge who responded to media questions also stressed how difficult it was to decide Ikeda’s fate. He said a number of other things as well:

• That when confronted with photos of the victims’ dismembered bodies, he looked for a few seconds before concluding that he does “not need to see these.”

• That despite initial concerns his “amateur” status would cause him to “get in the way” of the legal process, he learned a lot during trial and is glad he served in the case.

• That the panel used the Nagayama factors as the basis for their decision-making.

• That because of the legal requirement of lifetime secrecy, he cannot say whether his views were “shaken” during deliberations, but he was “forced to think about various things” as a result of serving on the panel.

• That he “cannot say” whether three days was enough time for thorough deliberation (an expression some listeners took to mean “we needed more time”).

• That Japan’s government “does not need to release more information” about how capital punishment is administered.

• That when serving as a lay judge in a capital trial, a citizen should “follow the law and look at the punishment, not at the defendant” because “if you don’t do that, you cannot do the job…As a lay judge, don’t think about participating in the system of capital punishment, just think about assessing the case.”

Some readers may sense that the lay judge’s last remark reflects avoidance and denial. I do too. Sadists and serial killers aside, it is not easy for one human to kill another. In order to do the deed, a person usually has to overcome inhibitions, some of which may be hardwired. On the frontlines of war, for example, many American soldiers purposefully shoot to miss—even when they are under attack and under orders to shoot to kill. Or at least they did in the past. Avoidance of this kind dramatically declined after U.S. Army researchers discovered this manifestation of courage or cowardice (take your pick) and reformed basic training in order to make killing in combat a more automatic and less deliberative response—and thereby more consistent with institutional imperatives (Grossman, 1995).

And so it is with capital punishment, an institution that asks humans to kill, and hence one that must provide mechanisms for overcoming the ordinary reluctance to do so. Japanese capital punishment has a variety of devices. The most common may be the phrase yamu o enai (“it cannot be helped” or “it is unavoidable”), which is used to explain and justify death penalty decision-making. This phrase is ubiquitous in Japan’s death penalty discourse. Prosecutors use it when seeking a sentence of death. Judges use it in their opinions at the trial and appellate levels. Defense lawyers employ it to argue that death is not inevitable for their particular client. Reporters and professors use it to describe and assess capital outcomes. And the Supreme Court, in its landmark Nagayama decision, placed this expression at the heart of Japan’s capital jurisprudence. The punch line of that decision says that after considering the many factors the Court deems relevant for making choices about who the state should kill, a death sentence should be imposed only if, all things considered, “it is unavoidable.”

Consider this formula one more time. Linguistically, it denies the very fact of choice for which the Court is ostensibly providing guidance. Psychologically, it enables its enunciators to distance themselves from responsibility for death penalty decisions. And ultimately, this expression provides a path around inhibitions that otherwise might impede efforts to carry out capital punishment.37

One sees similar signs of ambivalence and resistance toward state killing in statements made by the head judges in the Hayashi and Ikeda cases. At the press conference after Hayashi was sentenced to life, an alternate lay judge said that he and the other lay judges were much encouraged by a statement Judge Wakazono Atsuo made during deliberations. “In the end,” Wakazono apparently told his co-deciders, “the court and professional judges will shoulder all responsibility for the decision that this panel makes.”

Judge Wakazono’s statement was no doubt well intended, aiming to relieve the burden lay judges felt about the gravity of their life-or-death choice. Nevertheless, it is difficult to imagine a judicial pronouncement that more directly contradicts the central premise of the lay judge system, which is that citizens must take responsibility for deciding matters that matter, including decisions about death. Legal professionals and journalists say that Wakazono is well regarded by his peers in the judiciary and by the parties who appear before him. In a previous post he even taught legal trainees (shiho shushusei). That a judge of his caliber could deem it appropriate to make such an irresponsible statement about the responsibility for capital decision-making reflects the psychological difficulty of deciding who the state should kill.

Chief Judge Asayama Yoshifumi made a similar attempt to ease the burdens of state killing after he sentenced Ikeda Hiroyuki to death. “This is a conclusion of consequence,” Asayama said, “so as a court, we recommend that you file an appeal.” The next day, Japan’s newspaper of record put this quotation and reactions to it at the top of page one. When the lay judge who spoke at the post-trial press conference was asked what, if anything, he would say to Ikeda if they were given a chance to speak, the fifty-something man paused for several seconds before saying, “I would tell him what the chief judge said at the end of today’s sentencing: please appeal.”

Other commentators were less generous toward Judge Asayama. Most newspapers called his pronouncement “highly unusual.” Japanese trial courts always inform defendants of their right to appeal, and occasionally even hint that appeal would be a good idea, but they seldom express themselves as baldly as Asayama did. Ikeda’s lead defense lawyer was perplexed. “I don’t get it,” he said. “While recognizing the humanity of the defendant and his potential for rehabilitation, the court sentences him to death and then says ‘you better appeal.’ What is this?” An even edgier reply came from an executive prosecutor who lamented the judge’s presumptuousness: “The defendant is remorseful and says that he will accept whatever punishment decision is made, and this kind of recommendation is going to disturb his emotional stability.”38

There are two main interpretations of Asayama’s suggestion, and both probably point toward truth. First, the judge’s recommendation seems to reflect a lack of confidence about the lay judge panel’s decision. Indeed, some observers believe the decision was not unanimous, and that Asayama was merely doing what one or more lay judges had requested.39

The second interpretation meshes with the first. American research about the post-traumatic stress that capital jurors feel demonstrates the difficulty of acknowledging one’s own participation in a process that condemns someone to death.40 Judge Asayama’s recommendation that Ikeda appeal his death sentence may be another one of those devices long familiar to students of the psychology of killing who note that people often feel the need to “pass the buck.”41 A related point is reflected in the low lay judge appearance rate at post-death sentence press conferences. After Ikeda’s trial, only one lay judge attended, compared with an average of six lay judges per post-trial press conference for Japan’s first 116 lay judge trials (all of which were non-capital). The press conference following Japan’s third capital trial—which also resulted in a sentence of death—was attended by two lay judges, and the press conference following the fourth (also a death sentence outcome) was not attended by anyone at all.42

On November 30, 2010—the deadline for filing an appeal—Ikeda’s defense lawyers submitted one to the Tokyo High Court. It is hard to predict the outcome, especially since there is no relevant track record. In my view, Ikeda seems unlikely to receive a lesser sentence, for at least three reasons. First, Japan’s Supreme Court issued a statement in 2008 saying that lay judge decisions should be respected “as much as possible.” This directive is aimed at bolstering the legitimacy of the new trial system. In the past, efforts to create meaningful mechanisms for citizen participation in Japan’s criminal process were often marginalized and co-opted by legal professionals.43 Second, the Supreme Court’s directive appears to be working. Of the 145 lay judge trial outcomes that High Courts had reviewed as of September 2010, only eight (5.5 percent) had been overturned. Third, it is hard to imagine that the Tokyo High Court—widely considered the nation’s most conservative—will be any less appalled by Ikeda’s crimes than were the police, prosecutors, judges, and lay judges who have considered his conduct so far. If and when Ikeda is executed, one wonders what the six citizens who helped decide his fate will think about their participation.

The Season of Capital Punishment Continues

After Ikeda was sentenced to death, I interviewed Yasuda Yoshihiro, a defense attorney who has led Japan’s abolitionist movement for the last 20 years. Yasuda said he worried that lay judges would quickly grow accustomed to imposing sentences of death. “Perhaps this is part of our national character,” he observed. “We quickly get used to new forms of authority, and in the context of strong public support for capital punishment, I am deeply concerned that handing out the death penalty will be considered a lofty mission.”44

The lay judge system continues to be tested, with mixed results. In November and December, three more life-or-death decisions were made. The first two resulted in capital sentences, causing me to wonder whether Yasuda might be right. But the final capital trial of 2010 surprised almost everyone when it ended in acquittal. This section summarizes these three trials.45

Death for a Juvenile

On November 25, the Sendai District Court sentenced a juvenile to death for murdering two people with a butcher’s knife and injuring two others.46 The defendant—another disappointed lover—was 18 years old when he committed these crimes (the age of majority in Japan is 20), thus becoming the first minor to be sentenced to death since 2008, when the Hiroshima High Court condemned a young man who had murdered a housewife and her baby daughter in the “Hikari” case described earlier.47 After the Sendai death sentence, two lay judges appeared at a post-trial press conference, and one of them allowed himself to be photographed. “I cried all weekend before this sentencing day,” he said. “But I am letting you take my picture because I have done nothing to be ashamed of.”

Although the Sendai defendant confessed and said he would accept whatever sentence the court imposed, many observers believe his case required a more difficult judgment than the ones lay judges had to make in the Hayashi and Ikeda trials, for Japanese law still subscribes to the principle that juveniles should be protected and nurtured, not simply punished or extinguished. But like many other aspects of criminal justice in Japan, this principle has been pushed in a “get tougher” (genbatsuka) direction over course of the last decade, and the Sendai sentence seemed to ride that wave of punitiveness. All of the bereaved who testified at trial demanded a death sentence for the defendant, a troubled and troublesome youth who fathered a child with the young women who had left him and whose companionship he was trying to regain when he killed her elder sister (age 20) and her female friend (age 18). The defendant also stabbed the sister’s 21-year-old boyfriend. Then, after abducting the object of his affections, he beat her with a metal bar. The defendant had assaulted her on previous occasions, and had burned her with cigarettes, too. In what could be a case of the cycle of violence, the defendant was on probation for assaulting his own mother at the time of these crimes; she had often abused him when he was a child. In other respects as well, the defendant had a hard upbringing. He had dropped out of high school, his mother was often absent from home, she had lived with a series of violent men, and she had been in and out of the hospital to treat her alcoholism.48

On December 6, the juvenile’s defense lawyers appealed to the Sendai High Court. Their explanation to the press employed the same logic of remorse and atonement that were evident in the Hayashi and Ikeda trials: “The juvenile has come to feel that accepting the death sentence and dying is not the only way to atone for his crimes, and that another method is to atone by living and by continuing to cultivate a feeling of apology.”49 A few days later, the 21-year-old man who had been stabbed by the juvenile expressed anger over his appeal. “I do not want the defendant to atone by living,” this man lamented. “My true feeling is that I wanted him to accept the death sentence. The most important thing is for him to atone to the bereaved families who have lost their most loved ones. Death is the way to do it.”50

Another Death in the Family

On December 7, a lay judge panel in Miyazaki sentenced 22-year-old Okumoto Akihiro to death, for strangling and drowning in a bathtub his five-month old son and then burying the baby’s body in a dump, and for killing his wife and mother-in-law with a hammer and knife. This killer used to be a member of Japan’s Self-Defense Forces. Like Ikeda in Yokohama and the juvenile defendant in Sendai, Okumoto confessed to everything in the indictment and said he would accept whatever sentence the court imposed—including death. At trial, Okumoto’s defense lawyer said “you should hang your head and apologize for the rest of your life for the three lives you have snuffed out.” After sentencing the defendant, chief judge Takahara Masayoshi implored him to “continue praying that the three people you have killed will find happiness in the next world.”51

Okumoto said his motive for the triple murder was his desire to “be free” of the constraints of family life, and that this freedom included playing pachinko and consorting with women who work in the sex industry. Okumoto’s mother-in-law frequently rebuked him for not being a good husband and father, and Okumoto said he decided to kill her when he realized he could not stand her scorn any more. Having reached this decision, he then concluded that his wife would need to disappear too (lest she tell the police), and that if he killed his wife he would also need to kill his son, because a boy without a mother would have a hard life. The son of the dead mother-in-law demanded a sentence of death, and when it was delivered he expressed appreciation by saying that the decision “represents our feelings as victims.”

During trial, the professional judges provided the lay judges with no “family murder” precedents to inform their sentencing decision, apparently because they wanted the panel to consider this case “on its own terms.” Some analysts believe this was a peculiar position for the pro judges to take, not least because a man who killed five family members in Gifu prefecture in 2005 received a sentence of life.52 After trial, none of the six lay judges or four alternates appeared at a scheduled press conference, though one lay judge (a company worker) did reply to media requests for an interview. He said that the defendant’s remorse was shallow, that his hands shook when he voted in deliberations, that he cried when told of the outcome, and that the state, not citizens, “ought to take take responsibility for making life and death decisions.” He also said that the feelings of the bereaved “had a major influence” on the sentence. As in the other capital trials, this lay judge stressed that the case was “an extremely tough burden to bear.”53 The media again amplified this message, though some commentators came forward to lament the unwillingness of lay judges to talk after trial. Kokugakuin University Professor of Law Shinomiya Satoru said that “precisely because this is a death sentence, we need lay judges to speak at the press conference, but since they seem worn out right after making their decision, perhaps we need to create another opportunity for them to talk after more time has passed.”54

Other commentators criticized the court for flimsy reasoning about its decision. Aoki Takayuki, a former judge who is now Professor of Law at Surugadai University, accepted the capital outcome but puzzled over its justifications. “In a borderline case where either life or death could be chosen, a death sentence is certainly one possible judgment. But from the reasoning in this court’s opinion, I cannot tell what sentencing factors the lay judges emphasized.” Fujimoto Tetsuya, a Professor of Criminal Law at Chuo University, expressed a similar view. “Since the defendant is young and has no prior record, the Nagayama standards have not been satisfied. The trend towards imposing death sentences even when all the standards have not been met is dangerous; the standards must be strictly observed. If this had not been a lay judge trial, it probably would have been a life sentence.”55

Not Guilty

The Nagayama standards did not need to be “strictly observed” in the last capital trial of 2010 because the defendant was acquitted. On December 10, a lay judge panel of the Kagoshima District Court found 71-year-old Shirahama Masahiro not-guilty of the robbery-murder of 91-year-old Kuranoshita Tadashi and his 87-year-old wife Hatsue. Shirahama was indicted for breaking into the victims’ home in June 2009 and, in an attempt to steal money, murdering them by hitting their heads with a metal shovel more than 100 times (prosecutors said the victims’ faces looked like “noodles”). Shirahama was the fourth defendant to be acquitted out of more than 1500 who had received lay judge verdicts as of the date of this trial.56

Shirahama, a carpenter, denies ever being at the scene of the crime; his unconfirmed alibi is that he was taking a walk and dozing in his car when the murders occurred.57 Without a confession or any eye-witnesses, prosecutors relied on physical evidence, including eleven finger and palm prints taken from windows, drawers, and papers in the victims’ home, and DNA gathered from the crime scene. Of the 886 DNA tests that were done, only one matched the defendant, and this was sufficient for the state’s expert to conclude that Shirahama is “the only person in the world” who could have left the trace behind.58

Shirahama’s defense stressed at least seven elements of reasonable doubt: (1) that the defendant has never been to the scene of the crime, so the physical evidence must have been forged or fabricated by police or by the real killer; (2) that none of the defendant’s finger or palm prints were found on the murder weapon; (3) that the defendant is too old and weak to swing a shovel more than 100 times; (4) that no money was taken from the victims, so this could not have been a robbery-murder; (5) that the victims were beaten so brutally that the offender must have had a personal grudge against them—and yet the defendant did not know them; (6) that the foot and tire prints at the scene of the crime do not match those of the defendant; and (7) that there is danger in convicting someone on the basis of DNA evidence when there is no physical evidence that can be retested (the state used it all in conducting lab tests for this trial).

Altogether, 27 witnesses (mostly police) testified during the 10 days this court was in session, and deliberations lasted an additional 14 days (there were also 12 pre-trial sessions that lay judges did not attend). Many of the trial sessions ran overtime, and lay judges even visited the crime scene—for the first time since the new system started. This was a capital trial that took far longer than the four that preceded it. Some people said it took “too long,” while others said it did not take nearly long enough to examine all of the issues contested in this trial.59

Ultimately, the Kagoshima acquittal is rooted in the court’s recognition of the criminal justice principle which holds that a defendant must be presumed innocent until proven guilty (utagawashiki wa hikokunin no rieki ni). Some observers, such as former judge Kitani Akira, who acquitted some two dozen defendants during his thirty years on the bench, believe that this rule has often been respected in the breach, and that the lay judge panel in Kagoshima reached a decision professional judges would not have arrived at on their own. He might be right, for the Kagoshima court acquitted Shirahama even though it found he lied about never having entered the victims’ home, and even though it determined that the finger and palm prints and DNA were his. In Kitani’s view, a panel composed of professional judges might have inferred from the fact of the defendant’s dishonesty that he must have committed the crimes.60 Other observers are not so sure, including Tokyo University Professor of Law Daniel Foote, who believes the evidence in this case was so weak that it is best to think “professional judges would have reached the same conclusion on their own.”61 This too, is plausible, for the court’s opinion (which was written by professional judges) concludes that “there are many reasons to deny the defendant’s criminality” and that “the evidence taken as a whole falls far short of allowing one to infer the defendant’s guilt.”62

Whatever the answer to the counterfactual question—would pro judges have acquitted too?—many Japanese journalists, lawyers, and law enforcers were surprised by the outcome. After learning of Shirahama’s acquittal, one exasperated police officer in Kagoshima wondered, “How far do we have to go to prove someone guilty?” An executive prosecutor complained more generally: “Indirect evidence on its own is no good, and yet when we try to obtain a confession, people gripe about interrogation problems. I’m telling you, we’re not able to do investigations anymore.” And an Asahi reporter simply said “Wow, I never expected this.”63

So, one important context of the Kagoshima acquittal may be the advent of Japan’s lay judge system. But the broader context includes recent events in Japanese criminal justice which have raised serious questions about the integrity of the country’s criminal process. Three incidents are especially notable, and they may well have influenced the Kagoshima court’s judgment.

First, in a retrial that concluded in May 2010, the Utsunomiya District Court acquitted 63-year-old Sugaya Toshikazu, who had spent 17 years behind bars on a life sentence he received after being convicted of murdering a 4-year-old girl in Ashikaga (Tochigi prefecture) in 1990. The court ruled that Sugaya’s conviction was based on a false confession he made after prolonged and high-pressure police interrogations, and on the flawed testing of DNA evidence.64

A second case that has eroded trust in criminal justice officials is widely regarded as the most serious scandal Japanese prosecutors have ever experienced. In October 2010, Osaka prosecutor Maeda Tsunehiko was indicted for fabricating information on a floppy disk in order to increase the odds of convicting bureaucrat Muraki Atsuko of bribery (she was eventually acquitted). Two of Maeda’s supervising prosecutors (Otsubo Hiromichi and Saga Motoaki) were indicted for covering up his crime. The behavior of these prosecutors—and that of their supervisors as well—violates the values of truth and fairness on which Japan’s criminal process is supposed to be based, and it has provoked serious soul-searching among politicians and the public about how the nation’s prosecution system needs to be reformed.65

The third background factor for the Kagoshima acquittal is the most local. In February 2007, 12 citizens of Shibushi city in Kagoshima prefecture were acquitted of giving or receiving bribes in a local election four years earlier (one other defendant died during trial). All 13 had been detained for long periods of time and subject to harsh police interrogation. One suspect was even forced to trample on the names of his relatives (fumiji). If prosecutors and judges in Kagoshima are not embarrassed by this case, they should be: prosecutors because they failed to find or disclose evidence that would have proved the defendants’ innocence, and judges for allowing the defendants to be detained and interrogated on flimsy evidence for up to 395 days.66 One of the most striking parts of the opinion acquitting Shirahama is its emphasis on the duty prosecutors have as “representatives of the public interest” to find and disclose to the defendant evidence that is in his or her interest. Shirahama’s lay judge panel rebuked prosecutors for failing to fulfill this obligation, and it also chided police for conducting a “sloppy” investigation at the scene of the crimes.67 For residents of Kagoshima, these remonstrations rang a sadly familiar bell.

The Kagoshima acquittal is also rooted in two recent court opinions about “reasonable doubt”—the first of which also has a personal dimension. In the 35 years before Shirahama was acquitted, Japanese professional judges acquitted only four defendants in capital trials.68 The presiding judge at Shirahama’s trial, Hirashima Masamichi, was involved in one of those cases—a triple murder that occurred in Saga in 1989. In 2005, the Saga defendant was acquitted, and Hirashima subsequently served as an associate judge on the appellate panel that upheld his acquittal, employing much the same language about reasonable doubt that later would be used in the opinion acquitting Shirahama.69 The other judicial precedent comes from April 2010, when Japan’s Supreme Court sent a death penalty case back to Osaka District Court for further examination with the admonition that convicting someone of a crime involving only circumstantial evidence “requires evidence that does not make sense unless the defendant is the perpetrator.”70 This premise also underlies Shirahama’s acquittal.

It is impossible to know how sure Shirahama’s judges were—or even how many perceived reasonable doubt about his guilt. Six lay judges and two alternates attended the post-trial press conference, and when they were asked how they felt about acquitting someone whom prosecutors and survivors wanted sentenced to death, the first person to answer simply said “it is as written in the sentence, and that’s all there is to say.” All of the other lay judges echoed this view.71 In what has become a familiar pattern, these lay judges also stressed how “tough” and “hard” the trial was for themselves and for their families and co-workers—and how glad they are that they could participate in the proceedings.72

The Kagoshima lay judges also were asked why they had not posed any questions to the witnesses or defendant during trial (in most trials, lay judges ask many questions). One lay judge said “this was a very delicate case, so I left that up to the judge.” Another said “I did have questions, but since I’m not supposed to tilt toward the prosecution or the defense, I asked the judge to ask them for me.” And one of the alternates said he “did not want to injure the people being asked, so he left it up to the judge, who is used to doing this sort of thing.” These statements are interesting, but they only hint at the real reasons for their silence. The truth seems to be that chief judge Hirashima Masamichi asked the lay judges to submit their questions to a junior judge on the panel, who then consulted with Hirashima about what questions could be asked.73

The most difficult question these lay judges faced concerned the feelings of the victims who had demanded a sentence of death. One said “They probably think our decision is unfortunate, but since the defendant also has human rights, we had to make a judgment from a neutral perspective.” Another said, “It must be tough for the bereaved, but we had to decide based on the evidence.” A third stressed that “the defendant must be presumed innocent, and that’s what kind of decision this is.” A fourth said “I really feel sorry for the family members of these murder victims, but the lack of evidence was the number one cause of this acquittal.” And an alternate lay judge said that if he were one of the people who had lost a loved one, he would “have a feeling that is impossible to express in words. But since this was the fate and perspective of those of us who were chosen as lay judges for this case, I hope the survivors will understand.”74

But the survivors did not understand. After sentencing they said: “We feel extremely surprised, and this outcome is most unfortunate. Our hearts were not at all prepared for this result…We the bereaved still believe the defendant is the criminal, and we expect that prosecutors will appeal and obtain the correct judgment from a higher court.”75 During trial survivors had indicated what a “correct judgment” would be: death. They said that “nothing makes sense except a capital sentence,” and that “a criminal [like Shirahama] who deserves the death penalty must be executed.”76

So the survivors still want a death sentence—and they may get one. Under Japanese law, prosecutors can appeal acquittals, and they will appeal this one,77 for if the current verdict stands it could significantly shape death penalty decision-making in future cases.78 As Japan’s largest newspaper averred, the Kagoshima ruling represents “a major setback for investigation authorities”79 and has “toughened the criteria for obtaining a conviction.”80

As for Shirahama, who prosecutors claim was desperate for money because he wasted his monthly pension of 220,000 yen ($2500) on pachinko and booze, freedom after more than a year of confinement must feel good. “The lay judges expressed their will after objectively accumulating evidence and judgments,” he said. “And thanks to the lay judge system, I was able to quickly receive an acquittal.” Shirahama also said he was not afraid of the death penalty, and that he fully expected the court to acquit him:

“I was confident of an acquittal, from after my arrest all the way through. I have consistently said I did not do it. I have not wavered. This false accusation has been cleared away, and I feel very happy. Today I did feel a little uneasiness while I was waiting for the sentence, but now I have the same feeling as the big blue sky. I feel so refreshed that I do not know what to say.”81

Shirahama also seemed at a loss for words when he was asked what he thought of the court finding that he had lied about never being in the victims’ house and that it strongly suspected he had trespassed around the time the murders occurred—and ransacked the bureau where his finger and palm prints were found. “I don’t think I should be critical of what the court said. I didn’t go to the house, and I didn’t do it. Other than that, I don’t have any special feelings.”

Conclusion

Japanese lay judges will make more life-and-death decisions in the months and years to come—and more anguished and angry survivors will call for more hangings. Whatever the outcomes of those capital trials, they will do well to avoid three problems that plagued the trials described in this article: the absence of special procedures and protections for capital defendants; the scripting of trials before they occur; and confusion about the purposes a capital trial should serve.

Death Is Different

Death is different in kind from any other punishment. As the U.S. Supreme Court has observed, it “differs more from life imprisonment than a 100-year sentence differs from one of only a year or two.”82 In America, this recognition justifies a wide array of special procedural protections for capital defendants. Most fundamentally, due process is not enough; there must be “super due process.”

Japan has capital punishment but it does not have capital trials, because nobody knows until the penultimate session—when prosecutors make their sentencing request—whether the punishment sought is death or something less. This has several unfortunate consequences. Most notably, without a reliable basis for discerning whether a case is capital, there can be no promise or expectation of super due process. In Japan this means that there are no special guarantees for ensuring adequate representation by defense counsel even when the defendant’s life is at stake, there is no special sentencing hearing separate from the adjudication of guilt (where a variety of factors could be carefully considered), and there are no special rights to appeal or request clemency. There is not even a requirement for judges and lay judges to agree that a death sentence is deserved—a mere “mixed majority” is enough.83 By this rule, four of the nine persons sitting in judgment can conclude that the defendant should not be sentenced to death and a death sentence may still be imposed.84 The principle of “reasonable doubt” is supposed to govern the adjudication of guilt in Japan as it is in the United States, but surely an analogous principle should cover capital decision making—as it does in capital jurisdictions in America, all of which require jury unanimity in order to impose a capital sanction.85 Japan’s mixed majority rule also contradicts the core premise of its own Nagayama standards, which is that a death sentence is only permitted if there is “no other option.” When 44 percent of decision-makers conclude that death can be avoided, it hard to see how this requirement has been satisfied.86

In Japan, death is not different.

About two-thirds of all capital sentences in America are overturned on appeal for failing to satisfy the constitutional requirements of super due process. This pattern reflects both the high aspirations of American death penalty law and the poor performance of American capital justice. But law can fail in more than one way. If American death penalty law fails to fulfill most of its many promises, law in Japan fails by making few promises at all. This is a failure of aspiration.

Japan’s current system of capital punishment also handicaps defense lawyers. Not knowing whether life is at stake in a particular case, even the best attorneys have difficulty discerning the most effective strategy.87 Should the defendant be encouraged to acknowledge guilt and express remorse, and should the defense focus on why he deserves to continue living? Or should the defense challenge core prosecution claims? These questions are fundamental, and their answers should not depend on guesswork.88 As Osaka attorney Goto Sadato observes, “if the purpose of the pretrial process is to clarify what points will be contested at trial, then Japan’s failure to disclose whether a case is capital is a failure to disclose the most important issue of all: does the state want my client killed? This makes no sense at all, and it is grossly unfair to the defendant” (author’s interview, November 28, 2010).89

There is also the matter of defense lawyers’ time and motivation. The first lesson of economics is that there is no free lunch. Everything has an opportunity cost, because time spent on one case cannot be spent on another. How many defense lawyers would spend more time and energy developing a defense if they knew before trial started that their client’s life was on the line?

Japan’s current system seems especially ill suited for lay judge trials. The first 15 months of this system have demonstrated that the vast majority of lay judges take their responsibilities seriously.90 But if lay judges were told at the start of trial that prosecutors are seeking a sentence of death, would they not be even more motivated to consider the evidence carefully and ask relevant questions of the witnesses, the defendant, and each other? And when the time comes for deliberations, would they not be better prepared, because they would have had more time to consider what it means to sentence someone to death?

Lay judge trials also challenge a central premise of Japanese criminal procedure, that there is no need to separate the guilt-determination stage from the stage where punishment is decided, even when (as in the Kagoshima case) the defendant pleads not guilty. The assumption underlying this premise is that professional judges are trained well enough to make decisions about guilt without considering irrelevant factors such as the feelings of victims’ families. But research shows that this is a dubious assumption—and it may be especially so for lay judges. When Keio University Professor of Psychology Ito Yuji asked 130 university students to judge a mock murder case, 70 percent of those who heard a statement from the victim’s family reached a verdict of guilty, while only 46 percent who did not hear the statement arrived at the same conclusion. Thus, the odds of conviction increased by half as the result of hearing testimony unrelated to the question of guilt. When Japan’s lay judge system was introduced, regulations on criminal procedure were revised to say that “the examination of non-evidentiary factors should be carried out separately from the examination of evidence related to the crime.”91 This regulation is being ignored.