Body Image in Japan and the United States

Laurie Edison and Debbie Notkin, with Kobayashi Mika and Rebecca Jennison

Introduction

Laurie Toby Edison is a photographer and social-change activist whose work addresses body image issues in a variety of populations. Debbie Notkin is a writer and editor who has worked closely with Edison on three body-image related projects (Women En Large: Images of Fat Nudes: Familiar Men: A Book of Nudes; and Women of Japan, an as-yet-unpublished portrait suite). All of these projects are discussed in detail below.

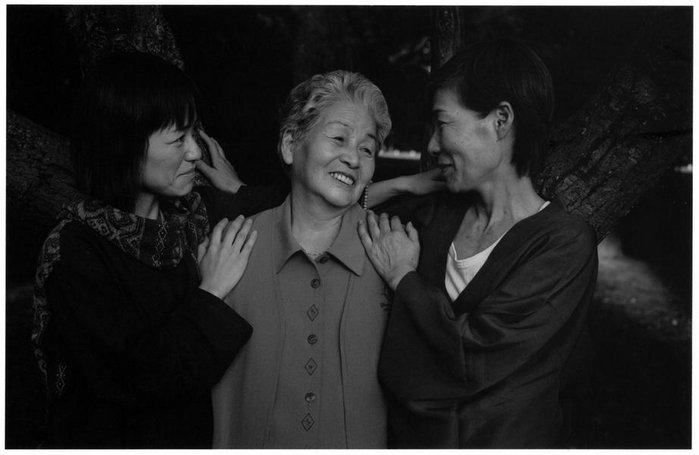

Kumamoto Risa, Teraoka Mika, and Kumamoto Reiko

I am 83 years old. My era was one of dominance of men over women, so my days were those of constant perseverance and restraining my own desires. I served my husband’s parents single-mindedly, and I couldn’t defy my husband in any way. . . .

-Teraoka Mika, Women of Japan model

In 1996, we first traveled to Japan, and that trip became the genesis for the Women of Japan project. In the intervening years, we have been consistently interested in how “body image” is explored in various Japanese contexts, and how it relates, in both similarity and difference, to the American contexts with which we are historically more familiar.

Although in the United States the term “body image” frequently references either solely or primarily to the body images of women, we use the term in a more inclusive fashion. In 2004, we completed an entire project and book devoted exclusively to men’s bodies.

To minimize confusion, we refer to ourselves together (Edison and Notkin) as “we,” but when we refer to one of us singly, we use the individual’s name. We also refer to our co-authors, Kobayashi Mika1 and Rebecca Jennison,2 by their names when we cite them. In addition, in the case of quotations from previously published work by an author or co-author, we have set those quotations into type the same way we set quotations from third parties.

Because “body image” itself is an almost exclusively western term, it is necessary to provide a full western/American context for both the theoretical concept and our history as American authors in working with this concept before discussing how the concept may be seen to apply in a Japanese context. A more comprehensive discussion of the term in first the American and then the Japanese context can be found below.

Our joint interest in body image from both an artistic and a social-change perspective dates back to the early 1980s, and our interest in Japan (most specifically the experience of women in Japan) began in 1996. To help create this context, we have included discussions of our professional histories, and our artistic and social change projects, as well as the role of body image in the lives of Americans as a basis from which we can discuss our experience in Japan.

A fundamental philosophical and aesthetic philosophy behind this work is that we want the viewer to experience the photographs as directly as possible. If a viewer sometimes wonders specifically who people in the photographs are, that can open up a larger space to reflect on the work.

We’ve written this article to discuss our direct experience in Japan and the United States, which includes photography sessions, workshops, conversations, and everything else that happens. We try to keep as closely as we can to telling a story that is as unmediated as possible. This includes having people speak for themselves and minimizing direct comparisons between the U.S. and Japan.

Working in Japan

In 1996, we traveled to Tokyo to attend the opening of the groundbreaking show Gender: Beyond Memory – The Works of Contemporary Women Artists3 at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography. This exhibit was curated by Kasahara Michiko,4 and featured twelve of Edison’s photographs from Women En Large: Images of Fat Nudes, along with excerpts from the text edited by Notkin.

The appearance of the work in this show was not an isolated event; Edison’s photographs had attracted attention in Japan from their earliest showings in the United States. Kotani Mari,5 feminist cultural critic and writer, had brought the work to Kasahara’s attention.

We could not, of course, anticipate the reaction to the work. We were concerned that we might be participating in the exoticization of images of foreign women. Nothing could have been further from the truth. The photographs were not only critically appreciated, they also evoked a personal reaction in many museum-goers: some were moved to tears, and many wanted to talk about what the photographs made them feel about their own bodies.

We arrived without having seriously considered the dominant paradigm, promoted in both Japan and the US, of Japan as a homogeneous society. After spending time in Japan meeting and talking with people, it became extremely clear that this is untrue. It was this paradigm, combined with the intimate and shared reaction to her work, that inspired Edison to begin Women of Japan, a suite of clothed portraits of women living in Japan. She chose the title “Women of Japan” in consultation with the women in Japan with whom she began the project.

Like Women En Large and Familiar Men, Women of Japan started with Edison wanting to photograph a particular group. She then works to depict everyone in that group inclusively.

Hagiwara Hiroko

I met Edison and posed for her to take my portrait. I had to face my features in the picture. I was ready to see how aging would unavoidably affect my looks. Because that happens to everyone, I am receptive of my own case. Yet I am prompted to have a metaphysical reflection by what the photographer captures beyond my expectation. It is hard for me to ignore the signs of intolerance and rigidity, which have been inscribed in my facial and body expressions in the course of my irrevocable fifty years. Here I am standing in front of the closed gate with my arms outspread. The pose the photographer selected out of many rolls of film seems to imply my whole life. What am I defending and from what? What am I facing? Could I have taken alternative ways? These are the questions which are significant only for me. Seeing my portrait starts as a purely personal experience. …

Edison always tries to treat the sitter not as a “still” model but as an active partner co-working for her project. She urges the photographed to face an unceasing chain of questions. That is how her art for social change is shared.

– Hagiwara Hiroko, Women of Japan model and collaborator6

The Tokyo exhibit sparked interest in Edison’s work in Japan that continues to this day. In the intervening thirteen years, Edison has been to Japan seven times, and has had six solo exhibitions. The first Women of Japan images were exhibited in 2000 at Third Gallery Aya in Osaka, curated by Aya Tomoko.7 In 2001, the National Museum of Art, Osaka, hosted “Meditations on the Body,” a retrospective of one hundred photographs from all three of Edison’s portrait suites, curated by Kasuya Akiko.8 The completed Women of Japan project was exhibited at the Pacifico Center in Yokohama in 2007.

Edison has given over twenty talks at universities, museums and art centers, plus many conversations with groups of students, housewives, and other interested groups. Most of these presentations were about the work; frequently, a panel of models discussed the issues raised. One of the goals of Edison’s social-change work is to create a context for these discussions.

More than thirty Japanese publications discussing the work have appeared. On a trip in 2000, in conjunction with the exhibit of Women En Large and Familiar Men at Kyoto Seika University, we met Kobayashi Mika.

We believe that the visual artist, especially when she is working in a context of social awareness, can bring a particular perspective to cross-cultural work. This is especially true in the case of a portrait photographer like Edison who works in collaboration with the people being photographed. Such portraits come not only from the photographer’s artistic sensibility, but also from her sense of who is being photographed: cultural, personal, environmental, and physical cues, what is and is not said or communicated. This interaction between aesthetics and intimacy, when combined with extensive community work (as described below) encourages communication across cultural boundaries.

Laurie, who is Jewish, and I have a lot in common. If you count from my Korean father, I am the second-generation Korean; from my mother, I am the third-generation Korean. … Laurie’s grandfather and my father left their own countries because of war and ethnic exclusion. They were swallowed up into the majority and lived in tension all the time. Talking with her, I didn’t feel like it was the first time we met, and I felt close to her.

– Kangja Hwangbo, Women of Japan model and collaborator

Kangja Hwangbo

Japan was my first experience doing cross-cultural work as an artist. I had twelve years of experience with complex community work in the United States. I found the cross-cultural work painstaking, complicated, and hard to do well. It constantly stretched me both aesthetically and intellectually. I asked questions, listened, listened, listened, asked new questions that arose from the listening, listened to why I was wrong, listened to how I was wrong.

At the same time, as a visual artist and a visual person, every waking moment that I spent in Japan or with anyone from Japan, I was constantly engaged in seeing the people, the body language, the gestures, the visual impressions that surrounded me.

Eventually, all the mass of images and words gave a coherent shape to Women of Japan. This is a perpetually open-ended process that is continuing as I write this. Each portrait is, in part, an expression of where the model and I were in that process at the time of the photo shoot.

– Laurie Toby Edison

In the Gender: Beyond Memory exhibit and virtually all other exhibits of Edison’s work around the world, explicative text excerpts by Notkin, the models, and other collaborators are used to help the viewer not only appreciate the aesthetics of the photographs, but also recognize the personal, social, and cultural context of the imagery.

In exhibitions we use words to provide context for the photographs, not to explain them. We usually do not put model’s texts next to their portraits. It’s important that the words don’t give people a dictated or preconceived image of the individual people. This creates a more direct experience of the work.

We are always very careful not to describe the models in our words. We simply ask people to write what they want to write. Some people write about themselves, but many choose other topics.

Edison says: “Part of the basic concept in all of the projects is that the models speak for themselves, and the portraits speak for me.”

Where a viewer may see simply the woman’s beauty in a Renoir painting or a Ukiyo-e portrait, and may never think about the model as a real person, in our work the juxtaposition of the text with the portraits makes viewers aware that these are pictures of real people.

Judgment of Paris

There is no mystery behind these tranquil, beautiful images in “Women of Japan.” Instead of mystery, there is an important sense of comfort. It makes me feel comfortable, just the way the women in the photographs seem to feel. Maybe it is not just comfort, but a feeling you would discover in yourself when you find contentment in what you are now. This is not resignation or self-satisfaction, but something coming from a positive decision to be yourself, to get rid of the images and roles pressed on you by society. – Yoshioka Hiroshi9

Nahamura Fumiko

Fine Art, Social Change, and Community Involvement

Edison’s work is fine art, which is also a tool for social change. A working artist all her life, she became a photographer initially to create Women En Large.

Artistically, I envision the world in black and white. I never considered being a color photographer. When I’m shooting, I don’t think about the message. I’m too busy working with the model to capture a mood, a facial expression, a pose in which they are comfortable, or a particular combination of visual balances. Each photograph is a stand-alone work of art.

– Laurie Toby Edison

Developing appropriate wide-ranging diversity in the photographs, as well as developing appropriate complementary text, requires a great deal of community work. From the very beginning of our collaboration in the United States, we have reached out to the community of people being photographed (fat women, men, and later Japanese women).

All of Edison’s portrait suites are designed to provide an opportunity for people in the group being photographed (fat women, men, women in Japan) to see people “who look like them.” In a media-saturated culture, whether in the U.S., in Europe, in Japan, in China, or around the globe, we are inundated with (photo-manipulated and literally unattainable) images of whatever the most conventional current representations of beauty happen to be, and almost no one outside the standard. Whether the marker is race, ethnicity, skin color, age, weight, class, ability, or anything else, those who do not come close to the conventional, unrealistic “norms” are, in our experience, hungry, often desperate, for attractive, respectful images of people they can imagine themselves being.

Each portrait suite includes a wide range of people in the group being photographed, including differences in age, race, ethnicity, class, size, etc. To accomplish this, we needed to show early photographs, hear people’s suggestions and ask as many questions as we could think of: what do you want to see in these pictures? Who is missing? What kinds of images do you wish you had available? What do you have to say about the topic? What works? What doesn’t? What could we be doing better? We use the responses to these questions to continually refine and improve the work.

Over and over, when people saw photographs of people like themselves, or like people they cared about, they were deeply touched, which translated into a desire to work with us on the project. People became invested in seeing the work completed, and widely available.

People she knew introduced Edison to models, from college professors to sewing-machine operators. Ideally, she and the prospective model would have tea, looking at some sample photographs and text and discussing the project. Very often the models had already been introduced to the work. She asked the models to decide where they wanted to be photographed. The places they chose reflected how they lived and perceived themselves. Edison wanted these portraits not only to convey a sense of the person being photographed, but also to provide a sense of their lives that went beyond a photograph taken in the moment.

I assumed that I would be asked to pose as a “model Ainu,” and so I prepared my traditional Ainu garment to be photographed in. And so when I was asked to pose as “My naked self” and as “a woman,” I felt suddenly quite nervous. To be honest, my real intention was to be photographed wearing the Ainu traditional dress. But, Laurie’s passion was communicated to me through the lens of the camera, your “naked self,” “pose as you like,” and yet I feel that my face was still quite nervous. Laurie said “relax” with a smiling face, and waited until I felt comfortable – I felt happiness from my heart. To sit or stand in front of a camera lens is no simple task, and this was definitely a good experience for me.

– Komatsuda Hatumi, Women of Japan model and collaborator

Shimazaki Naomi & Komatsuda Hatumi

Kobayashi Mika modeled for Women of Japan in 2000. She describes the experience as

a collaborative process that brought about interesting responses toward the questions that Edison posed for the models: how we feel about being a woman and being a Japanese. Many of the models are not aware of these questions in their daily lives and their answers show the variety of attitude they have toward the society and themselves.

Kobayashi Mika

For the American projects, we did thorough and multi-faceted community work: We presented slideshows of work in progress, published newsletters, met with interested groups in public spaces and people’s homes, wrote articles, and used every other method that seemed useful to do outreach and to communicate with the people we were including in the project.

As Americans working in America, we created our own version of an essentially American model, and while parts of it transferred easily to Japan, other aspects did not travel across cultures as well.

Although Edison’s previous portrait work was almost exclusively nudes, in Japan, given cultural attitudes toward public nudity, it was not possible to create the same kind of broad-based portrait suite of nudes, varied in profession, class, age, ethnicity, dis/ability, etc. that she did in the United States. Fortunately, this project’s focus on Japanese identity, as well as beauty, made clothed portraits far more suitable, and artistically rich. Removing clothing would have removed major signifiers of who people are, which would have diminished the work.

In our experience, to work in Japan requires Nemawashi (根回し). We were fortunate in our collaborators and colleagues in Japan. Many of the people we built relationships with over time were able to help us with sponsorship, or give us the necessary recommendations and introductions. Many people in Japan helped us examine our American experience and evolve our approach. They corrected our misconceptions about a country that was very new to us, and which we were only beginning to comprehend. Making this shift was not only crucial to doing the work, it also was enriching, informative, and satisfying, if sometimes also exhausting and confusing. Over the seven years it took to complete Women of Japan, our process constantly developed, changed, and refined.

As Hagitani Umi points out:

“The chain of introduction that Laurie has explained to me is a custom of Nemawashi (根回し). According to the fifth edition of the Japanese-English Dictionary by Kenkyusha (研究社新和英大辞典第五版), Nemawashi is explained as “trimming all but the main root of a tree to foster root development before transplanting.” Also, it is explained as “prior consultation; doing the groundwork; foregoing making a decision until behind-the scenes consensus-building is completed.” The Japanese version of Britannica Concise Encyclopedia (ブリタニカ国際大百科事典) says that the custom is rooted in the relationship among villages in ancient time where villagers made decisions unanimously. Hence, Nemawashi was a necessary condition for making consensus.”

It is of interest here that while we are most often invited to speak in Japan about the fine art and social change aspects of Edison’s work, we have also been invited to speak specifically about our practices of community involvement, how they work in America, and what we have learned about how they can translate into the Japanese context.

Tachibana Manami

My family’s mercantile history dates back about four hundred years. Before becoming merchants, my family was of Bushi (samurai) descent, serving the house of Oda Nobunaga, the lord who unified the feudal lords for the first time in Japanese history.) There is still armor from the samurai period left in the shed of my head family in Miwa. I practiced Japanese dancing, piano, flower arrangement, cooking, French embroidery, dress making, knitting, and horseback riding. I was an odd child in my family, reading science fiction and manga (comic books) and watching anime (animated cartoons). It is all right to read books, but science fiction and manga are for boys, not for girls, my family said. I was an odd child no matter where I was.

– Tachibana Manami, Women of Japan model and collaborator

Previous Projects

Our first project together was Women En Large: Images of Fat Nudes (Books in Focus, 1994). This book contains black-and-white portraits of fat women in the nude, along with quotations from the models, and two supporting essays by Notkin. It grew out of Notkin’s experience of being mocked for her weight, and became a ten-year process of taking photographs, doing community outreach as described in the previous section, collecting and refining text, searching for a publisher, and eventually self-publishing a best-selling photography book.

We learned far more doing Women En Large than can possibly be encapsulated in this article: one of the most important skills we developed was how to do diversity outreach, how to identify which kinds of images were missing, how to find models of color, models of different ages, models of different abilities, who wanted to participate and who brought not only their visual attributes but their lived experiences into the work.

We next collaborated on Familiar Men: A Book of Nudes (Shifting Focus, 2004), a book of black-and-white portraits of nude men, including aesthetic extracts from the full photographs and full-size versions of some of the extracts, along with the portraits themselves. This book also contains quotations from the models and other men, and an extensive essay on masculinity by Notkin and Richard F. Dutcher, which offered familiar and new challenges.

American men, we learned, are far less comfortable being photographed (especially in the nude) than American women. Men are not used to being the object of gaze. As a group, they find it more difficult to relax than women. They especially lack women’s cultural associations and familiarity with being photographed in the nude. But they seem to find a female photographer’s gaze more comfortable and less judgmental. Most of the men Edison photographed did indeed relax enough to work comfortably with her.

Men also have a different vocabulary for discussing the body and the politics of gender; for text to work, it has to be phrased differently and different contexts have to be provided. For example, “men are not used to being the subject of the gaze” becomes “men are not used to being photographed in the nude.”

Since we were working on Familiar Men while Women of Japan was beginning, finding out how much we had to adjust our style within our own culture was a helpful marker for the work in Japan to come. Women En Large was diverse, but Familiar Men went further, to include the widest possible range of people in a given category (in this case, men from 18 to 94, of a wide variety of races, ethnicities, classes, and dis/ability levels, among other factors), which also helped lay the groundwork for the diversity in Women of Japan.

Body Image in the United States

Merriam-Webster’s Medical Dictionary defines “body image” as:

a subjective picture of one’s own physical appearance established both by self-observation and by noting the reactions of others.

Wikipedia, which is a very useful reference for common perceptions of terms in daily use, defines “body image” as:

a term which may refer to the perceptions of a human’s own physical appearance, or the internal sense of having a body which is interpreted by the brain. Essentially a person’s body image is how they perceive their exterior to look, and in many cases this can be dramatically different from how they actually appear to others.10

We would prefer a definition that is less one-sidedly about appearance and exterior, instead including a person’s picture of how their body feels and works, and what it’s like to live inside that body. For the purposes of this conversation, this is our definition:

the way we feel about and perceive our physical bodies, as well as how the way we look is reflected in the eyes of other people and the many cultures we live in.

No group can be reduced to a single set of ideas and expectations, or even a small range. Perhaps the single most important thing we’ve gleaned from our community work is that counterexamples and varying views are ubiquitous. This does not negate the value of synthesis and examination of the dominant paradigm; it simply reminds us never to take that dominant paradigm at face value.

Kobayashi, after living for over a year in the United States (on both the East and West Coasts) says:

Through the experience of living in the United States, I noticed the variety of American body language. I also found that the differences in body language are deeply rooted in the varieties of communication. Many of the images of Americans available in Japanese media are quite limited in terms of race and class [i.e. usually presented as white and moneyed].

The United States is well-known as a diverse culture: while whiteness is certainly the unmarked state, white people are only 74% of the population, and in many urban and highly populated areas white people are no longer the majority. The omnipresence of media images, however, has had a huge leveling effect, leading to a situation where a significant percentage of people draw their images of a “perfect body” from a group they don’t belong to and to a standard they cannot ever match.11

How Americans feel about their bodies is constantly affected by their age, gender, ethnic/racial heritage, physical ability, location within the country, social class, and the standards of whatever community they find themselves in.

Debbie Notkin, April Miller, Carol Squires, Queen T’hisha, & Robyn Brooks

American body image has been oversimplified by cultural fat hatred to the point that many people believe the term to be related only to women and to be synonymous with “fat.” While this is by no means true — people’s body image issues range from height, skin color or skin tone, age signifiers, disability and more — nonetheless, weight has become the pivotal factor in how the vast majority of Americans (women and men) judge their own attractiveness (and health) and the attractiveness (and health) of others.

The contemporary American ideal of beauty in women is young, thin, and blonde (which of course, by definition, means “young, thin, and white”). In Victorian times, large women were the epitome of beauty. In the 1920s, the ideal becomes far thinner, although not that thin by modern standards.

In other eras, muscular male bodies have represented working with your body for a living, while a more portly figure has represented both economic and social success. Today, in men, the contemporary ideal is young (but not quite so young), muscular, at least average size, and white. Very short men, and sometimes very slender men even if they are not short, are outside any standardized American ideal of handsomeness. Blondness in men is optional. While many particular facial features or specific combinations have come in and out of fashion in America over the decades, the current trend is generally away from details of feature and toward the more general categories listed above. In previous periods, a particular facial shape or feature combination might have been definitional of beauty, such as the rosebud mouths of the 1920s. Now we see popular movie stars of both sexes with both long and round faces, both large and small noses, both wide and narrow eyes.

The role of whiteness in beauty in America is nuanced; whiteness is certainly the preferred state but it is possible, especially for a movie star or a performer, to be a person of color and be considered beautiful, as long as one’s features are comparatively “white” in shape and symmetry, one’s hair is not “too kinky,” and one’s presentation is not too daring.

Beyonce Knowles (Elle)

Thin-ness is everywhere and always paramount, frequently to the point of absurdity. Youth is almost as important as thin-ness; in fact, the American obsession with youth (in tandem with thin-ness), particularly in women, has crossed a threshold. While most idealized images of women include large breasts, there is also a sexual/ attractive ideal in which women appear barely pubescent and significantly undeveloped.

Another major factor in American body image is cleanliness. This is medical in origin, and translates into an intense concern for hygiene: good hygiene = good health. It must be noted here that in a consumer capitalist model where markets must continually grow, no one makes money telling people that their natural smells and body odors are fine.

Another effect of the capitalist model has been that when the market for women’s beauty and body products slowed down due to “saturation,” (i.e., women were spending as much money on these products as the analysts believed they could be cajoled into spending), the industry consciously turned its attention to men. The range of acceptable age and weight is far wider for men than for women, but men are still expected to be under forty, and simultaneously thin and muscled; not an easy trick.

Joe Ford

Body Image in Japan

Kobayashi says:

The term ‘image’ in Japanese relates more to how people other than oneself perceive oneself, in contrast to the American usage which includes how one thinks of oneself.

The term ‘body image’ is not translated into Japanese; rather, it is used as a foreign (not colloquial) word and its nuances are related to more specialized fields, such as art and cosmetology.

More familiar words that relate to this would be mitame (見た目) or gaiken (外見), a slightly more formal Kanji-originated word. They can be translated as ‘outer appearance’ or how ‘the others see one’s body or presence.” Gaiken expresses this more complexly; mitame is more immediate. Neither is limited to bodies or humans, and both are often used in a context of “You should not judge another person by their mitame or gaiken.”

Masaki Motoko & Kawamoto Eriko

In discussions about this article with our colleagues and collaborators in Japan, the most common response to “how do you feel about your body image?” was that this was an alien concept and not a way they thought about themselves. In contrast, during presentations in Japan, many people were both comfortable and articulate in discussing personal experiences and issues. They talked about issues of size, features, proportions and skin tones, sometimes in a feminist context.

Japanese must have had a totally different body image before the modern era. We can imagine this difference by reading ancient literature, or looking at old paintings. One of the most obvious is that the body seemed to be represented by our ancestors as something not so strongly associated with the physical substance.

I think it certainly reflects a Buddhist worldview. “Karada”, the Japanese word for “body”, includes the part “kara” which means “empty.” I suppose people in olden times in Japan saw the body as a flowing, ever-changing reality, not so much as a solid material.

– Yoshioka Hiroko

Tsunaoka Sadako

Many Japanese people we spoke to, when talking about bodies, began by saying something about lack of boundaries, or lack of edges. According to Yoshioka, “‘karada,’ (体) the traditional Japanese word for ‘body’ includes the part kara, which means ‘shape’ or ‘empty.’ Karada can be described as ‘empty flow.’” Yoshioka says that this term describes a body that is a form or husk, which the wind can literally pass through, while the Western concept is of a substantial, opaque, boundaried body. According to him, karada is an intimate, personal term for the body, too close to measure.

Fukuzawa Junko says: “I think that bodies have boundaries in the U.S., but they don’t have them in Japan.”

The more formal (originally Chinese) term shintai sokutei (身体測定) refers to measurements of the body (shintai (身体) meaning body in formal expression, and sokutei (測定) meaning measurement). This phrase is commonly associated with the annual school day on which students wait in line to have their heights, weights, and other measurements taken and recorded.

Japanese aesthetics look for, as a Japanese correspondent describes it, “long bodies and short feet.” Kobayashi adds, “In Japanese, the term toushin (頭身) describes the ratio of head to one’s full-body height (tou means head and shin means body). Hachi-toushin (or one’s head being one-eighth of one’s full height) is considered to be the ideal proportion. A ‘big face’ can be considered an indicator of impudent attitude.” The models frequently commented on the current youthful round-eyed, arched-nose, fair-skinned stereotype of beauty.

Bubu

A few of our Japanese correspondents describe bodies with a concept of, as one of them specifically puts it,

“‘soft line.’ This comes from ukiyo-e and the artwork of Leonardo da Vinci. … When I draw Japanese figures, I am usually conscious of the continuation of the soft curved line. I think that Japanese bodies are made up of the continuation of soft curved lines. The other side, American and European bodies, are made up of the continuation of hashed straight lines. Imagine manga and American comics. Japanese manga and ukiyo-e have soft curved lines, while American comics have hashed straight lines.”

Some of our correspondents in Japan report that many women assign a very high value to “esthe” (エステ) or grooming, down to very tiny details. Illustrating this, Kobayashi says, “Stress is placed on texture and smoothness of skin, and minute details of make-up.” It would seem that, especially for young women, grooming in general, and specific skill with make-up in particular, are almost indistinguishable.

Some correspondents described themselves as “uncomfortable” or “unfamiliar” with the term “body image.” Perhaps one reason is that, as one of our correspondents said, “it’s about the wrapper, not the body.”

We frequently notice comments about cleanliness in discussions of body image in Japan. There, cleanliness is a historically spiritual concept related to purity, growing out of both indigenous and imported Shinto, Buddhist and Confucian spiritual traditions. Kobayashi describes “various products such as deodorizers and odor-eaters both for bodies and for spaces in people’s homes. In Japan there is a long tradition of koudou (the art of identifying fragrance by burning incense), which has to do with the rituals of Buddhism. Unlike what I have observed in the United States, fragrances are more related to places than to individual people.”

The spiritual history of cleanliness, particularly in relationship to spaces, Edison was told, makes it possible for a Japanese homeowner or business to paint a very simple iconic representation of a temple gate on a wall, and have it not only widely recognized as “DO NOT PISS HERE,” but also respected. Men who need to urinate will step further away out of respect for such a sign.

Purity apparently also infuses other aspects of beauty, such as weight.

When I was in my mid-thirties, I thought that I wanted to have a beautiful body after I died, so I restricted my eating. I thought a thin body without fat, like a mummy, was a beautiful body that would never rot/decompose. For 3-5 years, I restricted my diet, and if I think of it now, it was a kind of ‘purification.’

– Hanashiro Ikuko, Women of Japan model and collaborator

Hanashiro Ikuko

From the time that Edison’s work was first exhibited in Japan, many people talked to us about their positive reactions to the photographs, including both sets of nudes, and the early Women of Japan work. They talked about standards in Japan of beauty and how uncomfortable these standards made them feel. Photographs from both Women En Large and Familiar Men were displayed publicly on trains and in train stations.

Ad in Japanese Train Station

In the United States, perceptions of conventional beauty rest more on age, race and weight for women, and race and shape for men, than on other factors. In Japan and elsewhere, the central issues are far more complex. Some of the images that affect Japanese expectations are the “Lolita-goth girls,” some manga drawings of women and girls, the images of super-thin women with big eyes, and the ubiquitous pictures of western women in advertising.

When I was in junior high school, I thought of becoming a comedian. Around that time, though, I was watching TV and I noticed that people laugh at a naked man, but, for some reason, people seem to detect a subtle atmosphere, and they don’t laugh at just a woman’s breasts.

– Chibikko, Women of Japan model and collaborator

Chibikko

“Straight hair and white skin are valued in Japan,” says one correspondent. Another says, “Skin-whitening products are being aggressively marketed everywhere here [in Japan] and in other Asian countries.” Yet another adds “It’s not about looking Euro-American.” On the other hand, some of our collaborators do feel that this is a product of Western influence.

For a long time, and still now, I have been feeling a sense of inconsistency or discomfort in the fact that I have a “woman’s body.” I think that is because my mind’s image of myself and the actual shape of my body are separated. I might have gotten used to, or become reconciled to my body, but before either of those things happened, I realized that “you can make your own body”. Make a body: change your body to that you imagine. When I realized this, my discomfort got better.

I like being thin. I want to achieve the imaginary body that shows as bony and inorganic, rather than round and soft. Because that is my mind’s image of “my figure.”

– Baba, Women of Japan model and collaborator

Baba

Although age is respected in Japan, what we have seen indicates that this does not extend to contemporary standards of beauty: youth is highly valued, and schoolgirls are put forward as both beautiful and sometimes sexualized. We believe this is one reason that women over 35 who spoke to us tended to be particularly moved by the photographs. They comment on how glad they are to see people who look like them; they say they see themselves rarely, if at all, in the media. Correspondents frequently talk about the valuing of thin-ness, round eyes, arched noses, and “approved” skin colors.

“I learned about my body from my mother. She always talked about fat, tall, big feet, breasts, and skin. I think my mother raised her daughter (me) to have values like her own, and of course her own values went up and down; her self-esteem was higher or lower at different times. My mother’s comments to me were always negative, so that she wouldn’t be told that her daughter was “impudent” when she grew up, so that her daughter wouldn’t be too proud of her appearance. “You’re too tall, you’re overweight, your feet are too big, your skin isn’t clear, your eyes are too small. If you don’t wear make-up, it will be unpleasant for others.

“I think she was worried that if women are too saucy, others (men) won’t like them. She thought women … are not meant to be empowered to live subjectively. As a result, her daughter (me) ended up with quite an inferiority complex. And so I feared being looked at as a woman.”

– Fukuzawa Junko

The disabled in Japan are often isolated and invisible. There is very little accessibility. There are certainly disability activists, including Taihen12, a disability theater company headed by Kim Manri. We felt it important to have them represented in the project.

The human body keeps changing all the time and can expand its possibilities infinitely.

Art should not be displayed, but should be what people living today need for their lives. So even if it is old, it must be infused with the breath of living now. In this sense, the human body is the highest art.

Human beings have a dual cosmos inside themselves. One is invisible: spirituality; and the other is material: physicality. Physical art for me is trying to confront and look at the dual cosmos of these human beings through bodies.

Physicality is needed to connect and integrate with the cosmos. The soul desires it and performs it as art. This is where I find the strong determination works. Art is created by the will of the cosmos.

In the process of clarifying my method of creation and reconsidering the process I engage in, I find art.

– Kim Manri, Women of Japan model and collaborator

Kim Manri

The importance of diverse images of women in Japan is undeniable. Without exception, the models appreciated the way they perceived Edison’s realistic portraits as standing in opposition to both Japanese and western stereotypes of Asian women. Both the models and the larger audience felt that this was the first time they recognized beauty and power in images of people like themselves. Including photographs of Nihonjin (日本人) women, Zainichi (在日韓国/朝鮮人), hisabetsu Buraku (非差別部落), Ainu, and Ryukyuu (琉球) women, as well as a Caucasian woman resident in Japan for many decades, provides a flavor of variety and complexity rarely shown in visual imagery of women, either in Japan or overseas. (Nihonjin is a multiply defined category. It is frequently used to exclude, but can also be used inclusively. Thus, it is possible to say that Zainichi, hisabetsu Buraku, Ainu, and others are, or are not, Nihonjin, depending on the speaker and the context.)

Finally, we want to acknowledge the profound importance of gestural and body language in examining body image in any culture. While we have observed a great deal about Japanese body language and gesture, we haven’t even begun to discuss this topic with the wide variety of people living in Japan that would be necessary to examine the topic in depth. We welcome the opportunity to learn what others have seen and learned about this.

Identity and Japan

All of Edison’s portraiture projects are about the beauty and power of the models, about making the invisible visible, about finding ways to bring out something essential about each person photographed, and about using imagery for social change. Women of Japan is all of that, and it’s also about Japanese identity.

I’ve never given the name “Japanese woman” to myself.

When they call me “Oriental,” “Japanese,” “woman,” “28 years old,” “single,” I murmur “It’s not ’bout me.

However,

I know that giving a name is a very important thing, perhaps.

’Cause we can’t recognize each other without it.– Okuda Yoko, Women of Japan model and collaborator

Okuda Yoko

The title Women of Japan in itself conveys some of the complexities of identity inherent in the topic. The phrases “Japanese women” (日本人女性) and “Women of Japan” (日本の女性) are very similar in English, but carry very different connotations in Japanese.

[My portrait] is shown under the title “Women of Japan” along with images of other women with diverse national and social backgrounds. The title is an appendage to the photographs, but it plays a decisive role when an audience reads the images. In Edison’s work I am one of the “Women of Japan.” I am a Japanese national by birth and a native Japanese speaker, living in the land geopolitically called “Japan” and holding a legal status fully approved by the authorities. Ideologically, I have always tended to be off “Japan” as a fixed categorization so as to play down and be critically objective of the cultural and political privileges of “being Japanese.” Here, however, I consider my image one of the least ‘off’ Japanese. Naming this series of portraits “Women of Japan” is Edison’s negation of “Japanese Women,” which could have easily been the expected title. But how much does my image negate “Japanese Women”?

– Hagiwara Hiroko

Hagiwara Hiroko & Fukuzawa Junko

It makes sense to talk about Women of Japan in two ways: one for people living in Japan, and one for people who are not from Japan and may not be familiar with Japan. People who are from Japan, or who have lived there for a long time, regardless of whether they have given much active thought to issues of identity, know what’s going on because it’s part of their world. For them, this work brings powerful and sometimes revelatory attention to issues that are always part of their lives and their context. People in Japan have an opportunity to see themselves and people they care about in the art.

We certainly don’t want to try to explain what Japan is like to them, and we are very wary (even after Edison in particular worked there so often) of trying to explain what it’s like in Japan to anyone else, either.

Coming to this work as foreigners and Westerners, we have to be aware at all times of colonialism, of potential racism, and of the anthropological issues which confront anybody from the west who is doing photography in Asia. We’re not unfamiliar with related issues; both previous projects were about groups that Edison, the photographer, is not a member of (fat women and men). We’ve had to learn a lot about how to bring visual art into a community context, in collaboration. Edison had extensive and challenging conversations with her collaborators in Japan during the nine years it took to complete the project.

For Edison the portrait relationship, the sense of the individual, is crucial. She works with individuals, not with concepts or races or genders. “If I was being anthropological or colonial, I couldn’t build the rapport I do with the models, and the results would be very different. When I took the first pictures for this project in 1998, showing them to the women who were in the photographs, and to other people in Japan involved with the project, was a key step. It was immediately clear that we were all comfortable with the work, and that’s how I knew I was on the right track.”

Laurie and I talked about gender, our cats, the era, the ethnic sense of value, and those matters that flow in a conversation. It was very delightful. … She laughed with me many times.

She has the power to pull out potential by pointing her camera. As Laurie left Okinawa, I was able to see my past from a new point of view.

– Hanashiro Ikuko, Women of Japan model and collaborator

Hanashiro Ikuko

When Edison speaks in Japan, she doesn’t talk about identity issues: she introduces the project and the models, who are an integral part of the presentation, take over. The people we talk to often say that this work is helping create a context to discuss issues of identity, and of course these issues are different from individual to individual.

I feel a disconnect and an incompatibility between myself as a woman and the system that blankets Japanese society.

– Fukuzawa Junko, Women of Japan model and collaborator

Fukuzawa Junko

Outside of Japan, it is more necessary to create a context for the work, so we do talk about the difference between the American and Japanese models of discrimination. The American paradigm is about race, with a huge invisible component of class. We want the diversity of images and text in Women En Large and Familiar Men to contribute to anti-racism work in the US.

Takazato Suzuyo

In our experience, the forms of discrimination are not the same in Japan. We certainly don’t claim to understand the full context, or most of the subtleties. But the testimony of our models and collaborators and our own experience confirm that the dominant paradigm is an exclusive and homogenous Japanese identity. Substantial groups of “minority people” (Buraku, Korean residents and their descendants, among others) are visibly indistinguishable from Nihonjin, using the term in its exclusionary sense. Other groups (such as Ainu and Okinawans), sometimes visually distinguishable, have their rich cultures devalued and rendered virtually invisible. All of these labels are contentious and politicized, and their meanings change as one moves through time and place. Our usage reflects the desires and choices of our models and collaborators.

I am a Korean born and raised in Japan. I am the third generation counting from my grandmother who first came to Japan. For over 70 years we have lived in Japan for successive generations. But, as it is difficult to obtain Japanese citizenship (I do not want to acquire citizenship under the present humiliating system), our rights as citizens have been wrested from us. … Sick and tired of living under such strictures, I came to question why I could not attain freedom. … There was a time when I hated myself for being a Korean. Conversely, there was a time when I hated myself for having Japanese characteristics. Now that I am 46 years old, I can think, ‘The fact that I am here (in Japan) is my history,’ and am able to affirm all aspects of myself. No matter what anyone says, I am a woman who is part of both Japan and Korea.

– Kangja Hwangbo, model and collaborator

Many of the women we worked with are activists on issues concerning women, from gender equality to minority rights. They are Nihonjin, Ainu, Zainichi, Buraku, Okinawans and others. These women have said they found the photographs, exhibitions and conversations very useful in their own work.

In conclusion, all we can say is that we have barely scratched the surface of a topic that can usefully occupy an army of observers and researchers for years. We hope that bringing the perspective of an American visual artist, an American social-change writer and editor, and scholars and activists of Japan to the topic, drawing on a combination of our own opportunities to observe and the lifetime experiences of our many correspondents, supporters and collaborators, has provided useful insights and questions.

Kotani Mari

Acknowledgments

A project of the scope of Women of Japan involves the cooperation and help of dozens of people and institutions over years. We would like to extend our heartfelt thanks to everyone on this list and anyone we may have inadvertently omitted.

Kansai Region

Aya Tomoko, Baba, Bubu, Chibikko, Hagiwara Hiroko, Hayano Junko, Hwangbo Kangja, Iizawa Chiaki, Ikeuchi Yasuko, Rebecca Jennison, Kasuya Akiko, Kawaii Yasuo, Kawamoto Eriko, Josiane Keller, Kim Manri, Kitahara Megumi,

Kobayashi Masao, Kumamoto Reiko, Kumamoto Risa, Sally McLaren, Masaki Motoko, Nakanishi Miho, Okuda Yoko, Takeshita Akiko, Teraoka Mika, Tsunaoka Sadako,

Watanabe Kazuko, John Wells, David Willis, Yoshioka Hiroshi,

Gallery Fleur, Kyoto Art Center, Kyoto Seika University, National Museum of Art, Osaka, Third Gallery Aya, Osaka

Kanto Region

Fukuzawa Junko, Kasahara Michiko, Kobayashi Fukuko, Kobayashi Mika, Kotani Mari, Matsui Midori, Michishita Kyoko, Ochiai Keiko, Shimada Yoshiko, Tachibana Manami, Tatsumi Takayuki, Yamanaka Toshiko

Pacifico Center, Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography

Hokkaido

Chikappu Mieko, Kawakami Hiroko, Komatsuda Hatumi, Shikada Kawami, Shimazaki Naomi, Suzuki Ryoko

Okinawa

Hanashiro Ikuko, Nahamura Fumiko, Takazato Suzuyo, Urashima Etsuko

United States

Beth Cary, Richard Dutcher, Hagatami Umi, Frako Loden, Dawn Plaskon, Motomi Rudoff, Peggy-Rae Sapienza, Mark Selden

Canada

Paul Novitski

Recommended citation: Laurie Toby Edison and Debbie Notkin, “Body Image in Japan and the United States,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 40-1-09, October 5, 2009.

Notes

1 Kobayashi Mika is a photography scholar and critic and photography exhibit curator. She has worked on Japanese photography exhibitions at the International Center of Photography in New York and the Museum of Modern Art in San Francisco. She has been an active collaborator on the Women of Japan project.

2 Rebecca Jennison is a professor at Kyoto Seika University. In 2000, she curated a joint exhibit of Women En Large and Familiar Men at Kyoto Seika’s Gallery Fleur. She is an active collaborator and advisor on the Women of Japan project and an Asia-Pacific Journal associate.

3 Gender: Beyond Memory – The Works of Contemporary Women Artists featured eleven artists from around the world and resulted in record-breaking attendance levels for the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography.

4 Kasahara Michiko has been a chief curator of the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography since 2006. She has curated many exhibitions since 1989, such as “Gender Beyond Memory” in 1996, “Love’s Body” in 1998, and “On Your Body, Contemporary Japanese Photography” in 2008. She was a commissioner of the Japanese pavilion in the Venice Biennale in 2005.

5 Kotani Mari is an independent Japanese scholar, best known for Evangelion as the Immaculate Virgin and Joseijou muishiki: techno-gynesis josei SF-ron josetsu (Techno-Gynesis: The Political Unconscious of Feminist Science Fiction). She has been an active collaborator on the Women of Japan project.

6 Hagiwara Hiroko is a professor in visual cultural studies and critical women’s studies at Osaka Prefecture University. She has authored several books on gender and racial politics in visual cultures of UK and Japan. Her recent publications include ‘Return to an Unknown Land: Sanae Takahata’s Quest for Self,’ n. paradoxa, vol.20, 2007. She has been an active collaborator and advisor on the Women of Japan project.

7 Aya Tomoko runs an independent art gallery in Osaka specializing in Contemporary Japanese Photography, including the work of Ishiuchi Miyako and Komatsubara Midori.

8 Kasuya Akiko was a curator at the National Museum of Art, Osaka, and is currently an Associate Professor at Kyoto City University for the Arts. She curated “Recent Works 26 – Laurie Toby Edison: Meditations on the Body” in 2001, and “A Second Talk: Contemporary Art from Korea and Japan” in 2002 at the National Museum of Art, Osaka.

9 Yoshioka Hiroshi is Professor of Aesthetics and Art Theory at Kyoto University. He edited the journal Diatxt., the critical quarterly of the Kyoto Art Center, and headed the editorial board of the Japanese Association of Semiotic Studies. He was the general director of the Kyoto Biennale in 2003 and the Ogaki Biennale in 2006.

10 The full Wikipedia article on “body image” can be found here.

11 For one view of how this affects specifically African American girls, see Kiri Davis’s short film “A Girl Like Me”.

12 More information about Taihen can be found here.