The Global Article 9 Conference: Toward the Abolition of War

John Junkerman

While much of

An affiliated conference in

The overflow crowd at the Global Article 9 Conference May 4th. All photos by Stacy Hughes, Peace Boat.

The Looming Threat to Article 9

The gatherings took place at a time when Article 9 faces the most serious threat of being abandoned since the postwar constitution was enacted in 1947. Prior to leaving office abruptly last September, then-Prime Minister Abe Shinzo—who had made revising the constitution the paramount goal of his administration—pushed a bill through the Diet that provides for national referendums on constitutional changes. The law, which takes effect in May 2010, started the clock ticking toward a showdown.

With this date in mind, the revision camp formed the Diet Members Alliance to Establish a New Constitution in the spring of 2007 with the explicit goal of “placing constitutional revision on the political schedule.” The alliance now counts 239 current and former members of the Diet in its ranks. Although the overwhelming majority are Liberal Democratic Party members, the group includes 14 members from the opposition Democratic Party of

The alliance held its own meeting in

This constraint was dramatically highlighted on April 17, when the Nagoya High Court ruled that the dispatch of

The unprecedented ruling, however, came in the text of the decision and carried no provision for enforcement. It thus left the status quo intact, and the government doggedly pledged to continue the mission to

Partly in backlash against

Article 9 on a Global Stage

This renewed support for Article 9 was evident in the spillover crowds that jammed the global conference to celebrate and advocate the renunciation of war. At the same time, the government’s continuing efforts to eviscerate and evade the spirit and substance of the clause, the incongruous reality of

The conference aimed to reframe the debate over Article 9 by removing it from the narrow confines of domestic Japanese politics and placing it on an international stage. “The war in

The conference slogan was “The world has begun to choose Article 9,” and numerous speakers pointed to the examples of

“Article 9 continues to inspire many people throughout the world,” declared keynote speaker Mairead Corrigan Maguire, who won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1976 for her efforts to end the conflict in

Nobel Laureate Mairead Corrigan Maguire.

In another keynote speech laced with the refrain, “Now is the time to put an end to militarism,” Cora Weiss, American peace activist and president of the Hague Appeal for Peace, told the crowd, “I have come to help spread Article 9.

Stressing the costs of militarism to the environment, economic development, and human health and security, video messages to the conference were sent by Nobel Peace Prize laureates Wangari Muta Maathai, founder of the Green Belt Movement in

Former Iraqi and

Among the 150-plus foreign guests attending from 40 countries and territories were soldiers who fought on opposite sides of the war in

Takato Nahoko, a young Japanese aid volunteer who was taken hostage while bringing emergency relief to

Other speakers included Tsuchiya Kohken, former chair of the Japan Federation of Bar Associations; South Korean lawyer and human rights activist Lee Suk-tae; former US Army colonel and antiwar activist Ann Wright; and Beate Sirota Gordon, drafter of the equal rights clause of the Japanese Constitution. Gordon, now 84 and the only person involved in drafting the constitution still living, spoke in Japanese and told the gathering, “I believe Article 9 can be a model for the entire world.”

A Determined Effort to Broaden the Base

The

The central organizers of the event were the Japanese NGO Peace Boat and the Japan Lawyers International Solidarity Association, who, since 2005, have spearheaded a campaign to promote the values of Article 9 on a global scale, as a concrete means of abolishing war (the global campaign’s web site is here). Given the ambitious scope of the conference, they formed an organizing committee in January 2007 to plan and publicize the events. The committee eventually grew to include more than 60 civil society organizations. Signing on as co-initiators were 88 prominent individuals, led by the writer Ikeda Kayoko, author of If the World Were a Village of 100 People; playwright Inoue Hisashi; popular fashion critic Peeco; and director of the Japan Association of Corporate Executives (Keizai Doyukai) Shinagawa Masaji.

Mobilization for the conference was boosted by the steady growth of the Article 9 Association (A9A) movement. These grassroots associations, created throughout the country in response to a 2004 appeal by Nobel laureate Oe Kenzaburo and eight other prominent intellectuals, now number more than 7,000. Many of these individual groups (as well as more long-standing groups, such as the Peace Constitution League [9-joren]) were active participants in the global conference, although the A9A network itself has a strict policy of not endorsing activities outside of the network.

The A9A movement itself was launched in part to free the defense of Article 9 from the narrow confines of the opposition Socialist (now the Social Democratic Party) and Communist parties, which historically were the bastions of the peace constitution but have become increasingly marginalized in recent years. While activists from these parties have been involved in forming some of the A9A groups, the movement has achieved a level of penetration that is unprecedented in the postwar history of Japanese citizens’ organizations. Their advocacy and educational efforts are widely credited with swinging public opinion back to support for Article 9. This is despite the fact that mainstream Japanese media has paid very little attention to the movement, from its very inception.

International participants toast Article 9 at the opening reception.

Strategically, the global conference was an effort to shift the movement from simply defending Article 9 to positioning it as a proactive component of the international disarmament campaign. Japanese activists have drawn inspiration from the 1999 Hague Appeal for Peace, the largest international peace conference in history, which set an agenda for the new millennium under the slogan “It is Time to Abolish War.” Article 9 has since been embraced by the Global Partnership for the Prevention of Armed Conflict (GPPAC), an international network of NGOs formed in 2005 at the urging of former UN secretary general Kofi Annan. Serving as the regional secretariat for GPPAC Northeast Asia, Peace Boat has strengthened its links to many of the international activists who participated in the conference.

The conference also aimed to broaden the base of support for Article 9 among young people, and it was largely successful in this effort. The bedrock of support for Article 9 has traditionally been the generation that experienced the devastation and lack of political liberty during World War II, but with the aging of that generation, the movement to defend Article 9 has struggled to shake the image that it is out of step with the times. But the crowds that gathered at Makuhari were diverse, with heavy participation of people in their 20s and 30s.

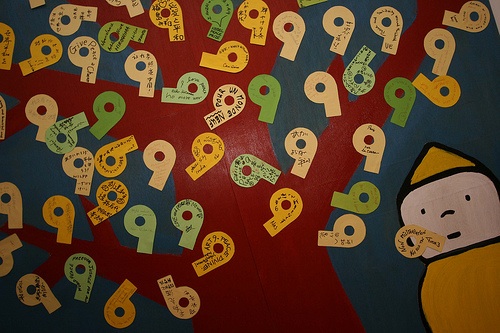

Peace Boat, which has been organizing round-the-world peace cruises since 1983, is staffed by and oriented to young people, and the group provided the core of the organizing staff and volunteers. Artist Naruse Masahiro designed a coordinated set of images for the conference, including a charming character that was given the nickname “Kyûto-chan” (a pun on “cute” and “kyû,” the Japanese word for “nine”). Naruse’s son and other young animation artists created a short film that opened the conference.

A series of graphics, featuring “Kyûto-chan.”

One youth-centered event was an Article 9 Peace Walk from

Suzuki Michiru, a 29 year-old woman, started in

The Article 9 Peace Walk arrives on stage May 4th.

Ash Woolson, a 6-year veteran of the

The first day’s events ended with a live concert, featuring the hit vocalist UA, veteran popular artists Harada Shinji and Kato Tokiko, and the up-and-coming trans-genre group Funkist, fronted by South African-Japanese vocalist Someya Saigo.

A boisterous web account of the Funkist performance reported, “Young and old, Japanese and foreigners, all perfect strangers, linked arms and rocked to the music. The arena became a tight unit and Makuhari Messe heated up. ‘My mother is South African,’ Someya told the crowd, ‘and my father is Japanese. Under apartheid, I wouldn’t have been allowed to come into this world. But now the color of my skin doesn’t matter. We are at peace here tonight. Let’s spread the call for peace from this spot to the entire world.”

Asahi columnist Hayano Toru quoted a pregnant UA on stage: “As one woman, as a mother, as a human being, as a spirit born on this earth, I believe the day will come when we hear the news that all of the wars on this planet have ended.” “Despite the difficulty of their lives,” Hayano commented, “young people, in their own words and ideas, in their own songs, are trying to create a ‘solidarity of kindness.’” Asahi editorial board member Kokubo Takashi, in a separate column, commented on the “lithe and natural words and conduct of those who gathered at Makuhari Messe. The constitution’s Article 9 has spread its roots farther and deeper among young people than we political reporters who regularly cover the Diet would ever imagine.”

Facing the Challenges of Globalizing Article 9

While the mood of the first day was idealistic and celebratory, the second day of symposiums and workshops focused on the problems and prospects of moving toward a world where Article 9 might spread and indeed become the model for “peace without force” that its supporters envision. Sessions were devoted to world conflicts and nonviolence, Article 9 within

The audience fills the hall for one of the conference symposiums.

The panel on

Takasato Suzuyo of Okinawan Women Act Against Military Violence noted, “What shapes

Joseph Gerson of the American Friends Service Committee pointed to the

It remains true that, since

Foreign and Japanese participants meet the press after the conference. From left to right:

Conference participants drafted a declaration, placing Article 9 in the context of a global disarmament agenda as well as a statement to the G8 countries that will be meeting in

The success of the conference and the international attention focused on Article 9 generated strong enthusiasm and optimism. But for Japanese activists, it also placed in sharp focus the large gap between the potential of Article 9 and the reality shrouding Japan—and the work that remains to be done. After an international participant called for a campaign to award Article 9 a Nobel Peace Prize, conference co-chair Ikeda Kayako responded in her closing remarks, “A Nobel Peace Prize? That’s out of the question. When I think of the actual situation of Article 9 in

Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution:

1) Aspiring sincerely to an international peace based on justice and order, the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes.

2) In order to accomplish the aim of the preceding paragraph, land, sea and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained. The right of belligerency of the state will not be recognized.

John Junkerman is an American documentary filmmaker and Japan Focus associate, living in