An Initiative for US-ROK Cooperation for Peace in the Korean Peninsula and East Asia: Policy Suggestions for the Obama Administration

The Peace Foundation

Seoul, Republic of Korea

December 2008

Introduction

North Korea, declared a member of the “Axis of Evil” by George W. Bush, responded by becoming a nuclear power. By the end of the Bush administration, however, it had completed Phase Two of the Beijing Six-Party agreement on denuclearization and normalization and in October 2008 was deleted from the list of terror-supporting states.

After the vacillations and policy reverses that occurred under Bush, much remains on the plate for the incoming Obama administration. The immediate outlook is clouded. The South-North train no longer runs, the cooperative schemes at Gaesong and Gumgang have been wound back to such an extent that they barely function, the Six Party process is stalled over the US demand for verification procedures and the US has suspended energy aid until North Korea accepts its “sampling” procedure. Rumbles of discontent from Pyongyang suggest it might be considering backing out of the process, even at this stage and at the inevitable cost.

The Obama foreign policy stance remains to be clarified, but the incoming president has made clear his readiness to talk to anyone and has relied to a large extent on members or associates of the former Clinton administration, which by 2000 had reached the brink or normalization with North Korea. Can we expect a return to 2000, when Clinton seemed about to pack his bags for Pyongyang, or to 2001, when Bush denounced North Korea in unforgettable terms?

Here, an influential group of South Korean citizens, academics, former officials, and religious leaders, following a detailed discussion of earlier North-South-US-UN-China negotiations, sets forth an ambitious agenda not just for peninsular denuclearization but for “peace and cooperation in Northeast Asia.” In this approach, the expanded importance of North-South negotiations is emphasized, while the role of the United States and China are fully recognized.

The Foundation at work

The Korean Peace Foundation’s home page is here:

What follows is a slightly edited and reduced version of the document, which may be consulted in full here:

The policy suggestions contained here in slightly abbreviated form are bold and comprehensive. In certain respects they are also surprising. Firstly, they refer scarcely at all to the very considerable political problems confronting South Korea itself. Yet, the Lee Myung-bak administration is closer in spirit to the harsh early George W. Bush than the conciliatory former one and its domestic policies show some signs of reversion to the repressive ways of the Park Chung-hee government of 30 years ago – as the Hankyoreh cartoonist wryly noted –

Former President Park Chung-hee tells President Lee Myung-bak, busily kicking at the Korean Teachers and Education Workers Union (KTU), the cable broadcaster YTN and the National Human Rights Commission of Korea, to “be gentle and take your time” in gaining control over organizations like these that are quickly losing their independence because Park took his time… eighteen years to be exact. (Hankyoreh Geurimpan, 13 December 2008)

How will South Korea’s civil society representatives associated with the following agenda paper address their own considerable political problems standing in the way of reconciliation and resolution of peninsular and regional problems? Secondly, the paper scarcely refers at all to Japan, which also currently is under an administration that is reluctant to engage North Korea on any issue except the abductions, but whose positive involvement is crucial to any project for Northeast Asian peace and cooperation. Thirdly, while the agenda depicted here of a “special” US-South Korea relationship is certainly in many ways attractive, it remains to be seen whether the Obama team will be able to adopt such a view of closeness and alliance, or whether it will instead prefer to follow established custom and see South Korea as secondary to Japan. It would require a considerable leap of creativity for it to think of the alliance with South Korea in terms of the closeness and sense of equality assumed here. Finally, will full-scale commitment to a US-led war on terrorism, as proposed here, be compatible with the peaceful goals for Northeast Asia promoted by the Peace Foundation? (GMcC and MS)

Foreword

With a sense of urgency, the Peace Foundation has prepared this paper for the new US administration for its consideration of its policy options for Northeast Asia and the Korean Peninsula for the purposes of not only achieving peace and stability in the Korean Peninsula and Northeast Asia, but also for the mutual benefit of the US and Korea.

Private discussions between the experts of the Peace Foundation and the US officials in the US administration, and open discussions with the Foreign Affairs Committee staff in the US Senate since 2007 have also provided a basis for this paper. The proposed policies and pledges offered by President elect Obama and his staff, and the policies and procedures of the Democratic Party, have been used as references.

I. Assessment of the 8 Years of the Bush Administration

1. Negative Inheritances – to be Overcome

Faced with an unprecedented crisis of the September 11 attack, the Bush administration made a critical mistake by responding to it in the old ways and giving away an opportunity to act on the international solidarity, caused a division in the global community rather than uniting the world. The unilateral policy has serious implications for the international community.

First, the Bush administration refused to honor certain agreements made with other states. The administration unequivocally denied the agreements made with the DPRK by the Clinton administration. The Bush administration ignored policy advice contained in the “Perry Report” which was prepared by Dr. William Perry, the North Korean Policy Coordinator appointed by the US Congress in consultations with relevant countries, and refused to implement the US DPRK Joint Communique which was the result of the high level officials meeting of both the US and DPRK.

In addition, the Bush administration took a series of actions that reversed US decisions relating to various international treaties, such as unilateral withdrawal from the Anti–Ballistic Missile Treaty (ABMT), and the refusal to ratify the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (CTBT). Such unilateral behavior and the lack of implementation of international agreements brought about serious declines in the credibility and moral authority of the US in the international community.

Second, the Bush administration ignored the “Negative Security Assurance (NSA)” for states that do not possess the nuclear weapons. The US released a report titled ‘Nuclear Posture Review’ in January 2002, which defined nuclear weapons as a part of offensive forces in the same manner as conventional weapons are categorized, and argued for the need to prepare for the capacity to launch “Preemptive Strikes” including deployment of small nuclear weapons against seven states including North Korea, Iran and Iraq. This is blatant rejection of the NSA, which promises no threats and/or attacks deploying nuclear weapons against states that do not possess nuclear weapons by countries that do.

It was a clear and unequivocal breach of the spirit of the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), which provided countries that do not possess nuclear weapons with the ‘Right to Peaceful Use of Nuclear Energy’ and the NSA in exchange for recognition of the possession of nuclear weapons by the five nuclear power states. In doing so, the US provided North Korea and Iran, the so-called ‘bad boys of the world’ with excuses to develop nuclear development programs. The Bush administration, consequently, drove the DPRK to become the ninth nuclear developing state in the world due to its misguided analysis of circumstances and policies.

Third, the Bush administration seriously damaged the authority of the United Nations (UN) by ignoring UN resolutions. The US labeled North Korea, Iraq and Iran as the ‘Axis of Evil’ in 2001 after the 9/11 attack, and President George W. Bush demanded the government of Iraq to abolish Weapons of Mass Destructions (WMD) and called for regime change in a speech at the UN in August 2002. Although the Iraq government did allow UN weapons inspections, the US proposed a resolution to invade Iraq to the UN Security Council in February 2003. On March 20 2003, the US, along with the United Kingdom and Australia invaded Iraq without the relevant UN Security Council Resolutions.

2. Positive Achievements – to be Continued

The unilateralism in foreign policy by the Bush administration in the last eight years has led to a precipitous weakening of US leadership in the international community. Exclusive reliance on hard power in the “War against Terrorism’ has caused US moral authority to plunge. Nevertheless certain positive outcomes of the legacy of the Bush administration’s foreign policy ought to be recognized from the perspectives of Northeast Asia and the Korean peninsula. Such outcomes deserve to be inherited and nurtured by Obama administration.

First, the Bush administration has completed the realignment of the US-ROK alliance. The US–ROK alliance has been the bedrock of stability and peace in East Asia and the essential element of security on the Korean peninsula in the past half century. Subsequent to the end of the cold war, security circumstances in the East Asia region have been changing fast due to, among others, the rapid rise of China, changes in the US strategic interest in the region, as well as the growth in national power of the ROK.

The US completed the realignment in its relations with North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and Japan in 1990s. The realignment of the US–ROK alliance started in the early 1990s also, but was suspended due to the death of Kim Il Sung and the first DPRK nuclear crisis.

The Bush administration revived the process in 2003 and has nearly completed transformation of the cold war style alliance between the US and ROK to one that would befit the 21st century. Through this process, the US and ROK reached a common recognition that the US–ROK alliance is still important, just as it was during the cold war era. Thus, the US-ROK alliance has been realigned as a global partnership, which calls for close dialogue and joint action in response to various global issues, in contrast to a military alliance, which had at its core the defense of the Korean peninsula.

Since the above noted process has reached a substantial stage of completion, no significant change in the basic framework of the new US–ROK alliance is expected after the Obama administration takes office. This is a vastly improved situation compared to the confusion and conflict that erupted as a result of the Bush administration’s attempts to realign the US–ROK alliance shortly after the Roh Moohyun administration took office in ROK. Apart from a few bilateral issues such as the Free Trade Agreement, US-ROK cooperation should expand to international issues such as the DPRK nuclear issue, the regional security framework, and other global issues.

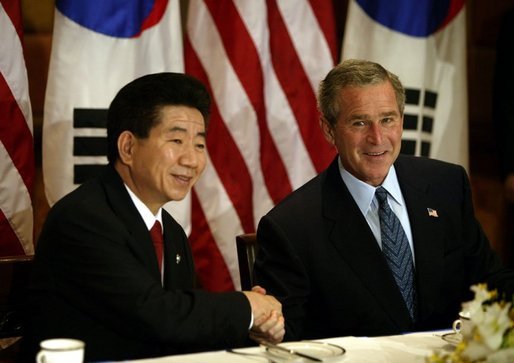

Roh and Bush at the White House, October 20, 2003

Second, the Bush administration started direct talks with DPRK. President Bush demonstrated a dramatic policy change in order to complete the second phase of DPRK nuclear issues before the end of his second term. Since the DPRK conducted the nuclear test on October 9, 2006, the US started direct talks with it. Consequently, several important milestones such as the dismantling of DPRK nuclear facilities, the deletion of the DPRK from the list of State Sponsors of Terrorism as well as exemption of the DPRK from the Trading with the Enemy Act have been achieved. The Bush administration should be given proper credit for such achievements.

The Bush administration shifted its misguided hardline policy towards the DPRK to a dialogue-based approach after the DPRK conducted a nuclear test. Even though implementation of the 1994 Geneva Agreed Framework was suspended in the early days of the Bush administration, the present status of this matter is in fact beyond the achievement of the Geneva framework in view of the refreezing of DPRK nuclear facilities, the return of the IAEA inspectors, the completion of the DPRK’s declaration including operating records of the Yongbyon facilities and the near completion of the disabling of 11 nuclear facilities. The dialogue and cooperation between the Obama administration and DPRK will need to be based on trust. It will be up to the new administration to achieve a nuclear–free Korean peninsula by ensuring safe treatment of nuclear materials and nuclear weapons and thorough verifications of both declared facilities such as the Yongbyun facilities and undeclared nuclear facilities.

Third, the Bush administration has established the foundation for a system of peace in the Korean peninsula and a multiparty security system for Northeast Asia. The comprehensive approach, which has been developed as a prescription for the DPRK nuclear crisis, is indeed one of the Bush administration’s positive achievements. The worsening of the DPRK nuclear issue that resulted from US unilateralism and DPRK protests in response had reached the level that could be resolved only by a comprehensive approach. The comprehensive approach made possible discussions about ‘building a lasting peace mechanism in the Korean Peninsula.’ The ‘Peace Forum on the Korean peninsula’ is yet to be established as agreed in the September 19 Agreement, due to delays in the completion of the second phase denuclearization process, but common understanding of the need for it has indeed been established.

Meanwhile, discussion on a Northeast Asia Peace and Security mechanism are underway. The working group for said mechanism within the framework of the Six–Party Talks has had a number of meetings and is circulating draft ‘Guiding Principles’ which aim at providing a basis for regulating the relations of Northeast Asian countries. Peace and security in Northeast Asia would step up to a higher level system if, as President–elect Barack Obama said, a new and lasting framework for collective security in Asia could be put in place, going beyond transitional means of dialogue such as the Six–Party Talks.

II. The Role of the US in Resolution of DPRK Nuclear Issues

1. New Approaches to DPRK Denuclearization

DPRK nuclearization is not only a serious security threat to the ROK but also to security of the US in the event DPRK nuclear weapons get into the hands of terrorist groups. That is why both the US and ROK pursue, as the first priority, “DPRK’s full and complete abandonment of all existing nuclear weapons and programs”, as declared in the 9.19 Joint Statement signed in 2005 by the Six–Party Talks. In addition, the US and ROK pursue the DPRK’s complete termination of any testing, production, and deployment of nuclear missiles, as well as exports of missiles and missile–related technology and equipment which go beyond the Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR), as agreed by the US and DPRK and documented in the US–DPRK Joint Communiqué of October 2000.

The Bush administration also opposed proliferation of Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD), but it took an approach of pressuring DPRK to abandon its nuclear program completely first and stated that the US would assure DPRK security and normalization of the US–DPRK relations only after the DPRK enters the stage of complete denuclearization. However, this approach backfired because it heightened DPRK’s concerns for its own national security and led the DPRK to expand its nuclear program considerably, including testing of a nuclear bomb. Consequently, the Bush administration’s pressure tactic gave more time for the DPRK to develop its nuclear weapons instead of resolving the issue.

The new US administration and the ROK government cannot afford to repeat mistakes made by the Bush administration. A new approach must be conceived for the full and complete abandonment of DPRK nuclear capacity within the first term of the Obama administration. Dr. William Perry, former NK Policy Coordinator, suggested a “Comprehensive and Integrated Approach” to DPRK denuclearization issue in his report, which also included assessment of four other approaches, such as the “Status Quo”, the “Undermining” of the DPRK, the “Reforming” of the DPRK, and the “Buying” Our Objectives.

Perry’s proposed approach, which was also dubbed a “Two–Path Strategy”, advocates enhanced engagement rather than continuing pressure on the DPRK. It stresses the need for reducing the security threat felt by DPRK in order to convince the DPRK that it can indeed achieve peaceful co–existence in the international community and economic development. The Perry approach does not simply rely on the goodwill of DPRK; it contains a provision of strong punishment in the event of DPRK noncompliance. Such a provision is expected to function as a countermeasure against the hawks within DPRK.

However, changes since the announcement of Perry Report should be noted. Among those, positive factors include the fact; (a) the Obama administration could get up to speed with minimal time necessary to assess the policy options, since it will inherit the Bush administration’s already modified policy, (b) that Republican opposition to the Obama administration’s continuing of current US policy towards DPRK will likely be minimal for the same reason, (c) that the Democratic Party’s dominance in both chambers of the Congress is likely to yield speedy consensus on policy choices and their implementation, (d) that the DPRK has come a long way through its experiments for economic reform with the 7.1. Economic Measure and Gaesong Industrial Zone, and (e) that the DPRK may want to reach a new turning point soon in view of Kim Jongil’s age. Negative factors include the fact that the DPRK already possesses nuclear weapons which have already been tested and lukewarm attitudes of both ROK and Japanese governments toward engagement with the DPRK.

The fact that the DPRK was aware of, and largely agreeable, to the conclusions of the Perry Report raises hopes for successful developments this time. It is unclear, however, whether the DPRK leadership is still amenable to the Perry Approach. In the event the DPRK rejects the Perry Approach now, the US will have to pursue a different type of relationship. If, however, the DPRK still finds the Perry Approach acceptable, the ultimate goal of denuclearization, peace and stability in the Korean peninsula could be achieved by strengthening the positive aspects discussed above and minimizing the negative elements or finding a way to convert them into positive elements.

William Perry visits Kaesong Industrial Zone, North Korea, in 2007

New Beginning of the US DPRK Dialogue: “The 2000 US–DPRK Joint Communiqué”

From the perspective of recovering trust between the US and DPRK, it is preferable that the US-DPRK Joint Communiqué, which was announced in Washington in December 2000, serve as the starting point of a new relationship. The 2000 Communiqué was announced after Cho Myung–rok, the first vice chairman of the DPRK National Defense Committee, in the capacity of a Special Envoy of Kim Jong–il, visited Washington during October 9~12, 2000 and delivered Kim Jong–il’s private letter to President Clinton.

The 2000 Communiqué contained key points of agreement including (a) a drastic improvement in the US–DPRK relations, (b) transition to guaranteed peace system through signing of the agreement for termination of the Korean War, (c) preferential economic cooperation and exchanges, (d) suspension of missile testing during negotiations, (e) compliance with the Geneva Agreement for nuclear–free Korean peninsula, (f) cooperation in the area of humanitarian efforts, and (g) a visit to the DPRK by Secretary of State Albright to prepare for the visit by President Clinton. Indeed, Secretary Albright visited Pyongyang on October 25, 2000. At the same time, preparations for a US–DPRK summit meeting were in full swing, however, the summit meeting did not materialize.

The present circumstances are significantly different from those when the 2000 Communiqué was announced 8 years ago. The DPRK possesses nuclear weapons, which have been tested. Consistent progress has been achieved in negotiations, as evidenced by the 9.19 Joint Statement (in 2005), the 2.13 Agreement and the 10.3 Agreement (in 2007), all of which occurred within the framework of the Six–Party Talks, in addition to bilateral agreements reached between the US and DPRK. With a Democratic president, circumstances may be ripe for revival of key elements of the 2000 Joint Communiqué.

The next US administration is advised to pursue a comprehensive approach which will include a variety of incentives aimed at inducing DPRK to abandon nuclear weapons, while utilizing the 2000 Joint Communiqué as the basis and the point of reference in combination with the 9.19 Joint Statement and subsequent agreements. The US could offer, either unilaterally or jointly with the international community, numerous incentives including: (a) the establishment of partial or full diplomatic relations; (b) a written assurance, signed by the US president, for national security for the DPRK; (c) further relaxation of various sanctions against the DPRK; (d) the provision of energy supplies as a part of the multilateral program; and (e) economic aid. Additional measures include DPRK application for re–entry to the NPT and the IAEA combined with starting of the negotiations for the construction of a new light–water reactor.

The third phase process for DPRK denuclearization, which needs to be pursued by the US, should be implemented in a comprehensive way, as declared in the 9.19 Agreement. The success of the comprehensive approach towards DPRK denuclearization will depend on implementation of a portfolio of three key components, which would include (a) the normalization of US–DPRK relations; (b) support for the reform and opening of the DPRK, and (c) the Collaborative Threat Reduction program (the “CTR–NK Program”). In view of the idiosyncrasies of the DPRK system, it is desirable to pursue the resolution of the DPRK human rights issue in close relationship to the normalization of the US–DPRK relations, but independent of the three–element portfolio noted above.

The comprehensive approach that the next US administration is recommended to pursue does not conflict in any way with continuation of the Six–Party Talks. At present, the Six–Party Talks include five working groups in addition to the chief negotiator meetings and the Korean Peninsula Peace Forum. The five working groups concentrate on the following areas: (1) Denuclearization; (2) Normalization of the US–DPRK relations; (3) Normalization of Japan–DPRK relations; (4) Economic and energy cooperation and (5) the Northeast Asia peace and security mechanism. The on–going approach to normalization of relations is expected to remain largely unchanged while a more progressive approach is expected towards the inducement of reform and opening of DPRK society. In addition, the CTR–NK Program is likely to integrate tasks of the three working groups that handle denuclearization, energy and economic development, and the Northeast Asia peace and security mechanism.

2. Formulation of Policy Option Portfolio for Resolution of DPRK Nuclear Issues

(1) Two–stage Normalization Process of US and DPRK relations.

Mutual trust should undoubtedly be a solid basis for pushing the third phase process. Otherwise, it risks repeating the vicious cycle of reaching an agreement, violating it, suspending implementation, the crisis of a complete breakdown, and reaching another agreement. In order to avoid making the same mistake, priority should be given to the normalization of the US–DPRK relations. The normalization process should begin with an exchange of visits by high ranking officials, through which mutual trust may be regained.

Establishing Diplomatic Representative Offices

The US has two approaches to establishing diplomatic relations with other nations: full and partial diplomatic relations. While the former requires consent by the US senate, the latter can be done under the authority of the US executive branch alone. The US Congress requires DPRK to meet a number of demands for full diplomatic relations with the regime. However, attaching numerous conditions only complicates efforts to acquire full diplomatic status as well as to resolve the nuclear problem of the DPRK. Given this, the US should not hesitate to give the DPRK a partial diplomatic status if the process is in motion.

Building partial diplomatic relations with DPRK will result in significant progress in resolving nuclear problems. The US administration needs the authority to install representative offices both in Pyongyang and Washington and to appoint charge d’affaires for nuclear negotiations with DPRK and agreed verification of nuclear programs on a regular basis.

Forming Full Diplomatic relations

Forming full diplomatic relations with the DPRK requires approval of two-thirds (67 members) of the 100 US senate members. Without US Senate approval, it would be impossible to allocate a budget for management of an overseas representative office and appointment of ambassador, all of which are needed to maintain full diplomatic relations.

Currently US Congress preconditions including resolving a wide range of problems from the dismantling of nuclear programs to misbehavior including human rights violations, bio–chemical weapons, ballistic missiles, counterfeit currency and illegal drug trade. In order to normalize relations with the US, DPRK first needs to obtain congressional consent to an agreement to be reached between the US and DPRK.

If the DPRK is found cooperative in abandoning its nuclear programs and resolving problems with bio-chemical weapons, ballistic missiles, human rights violations and other international misbehavior, the US Congress should give the go–ahead to full diplomatic relations with the DPRK. If any significant progress is deemed to be made, the US Congress should not hesitate to grant Most–Favored Nation (MFN) status and to lift trade sanctions against the regime.

(2) Support for Reform and Opening

Lifting Financial Sanctions and Supporting DPRK membership in Multilateral Financial Institutions

The 10.3 Agreement that followed the 9.19 Joint Statement is now entering a final stage of implementation. On June 27th, a day after the DPRK submitted its nuclear declaration to China, the DPRK was excluded from application of the “Trading with the Enemy Act”. On Oct 11, 2008 the DPRK was also delisted from the “State Sponsors of Terrorism.” This paved the way for the DPRK to receive humanitarian and other international assistance as well as to borrow from multilateral international financial organizations and introduce dual-purpose products and technology. In addition, the DPRK may enjoy MFN status and receive credit guarantees provided by the US Export–Import Bank.

Despite the political symbolism that can benefit the DPRK in many ways, various international sanctions and the UN restrictions stipulated by the UN Security Council Resolution 1718 still get in the way due to the fact that the DPRK is still classified as a state that threatens security, hews to communism and violates human rights. In addition, deleting the DPRK from the “List of State Sponsors of Terrorism” did little to relax export controls against DPRK, which is still required to meet a number of additional conditions and procedures to receive assistance from international financial bodies. Excluding the DPRK from “Trading with the Enemy Act” does little to ease the highest tariff rate against the regime. Given this, it seems hard to expect any significant increase in DPRK exports to the US before a bilateral trade agreement is reached.

On the financial front, the “Patriot Act” constrains financial activities of the DPRK in a significant way. The Feb. 13th Agreement certainly eased financial restrictions against the regime by allowing financial transaction with BDA. But there was no more. For example, financial institutions turning out to have had a record of being involved in illegal DPRK activities are not allowed to engage in financial activity in the US, which is why they are reluctant to involve the DPRK in their financial activities. In addition, complicated procedures aimed at discouraging illegal activities play a part in containing financial transactions with the DPRK. This limits much trade to cash or barter transactions.

The incoming Obama administration has good reason to start negotiations with the DPRK to relax financial restrictions. At present, the DPRK cannot conduct financial transactions with international banks, except in a few cases through Chinese banks, and the restricted account transaction causes great difficulty in pursuing international trade. Thus, the US needs to lift financial obstacles against the DPRK under the conditions that the regime should disengage from money laundering, sponsoring terrorism and illegal criminal acts.

Furthermore, the US needs to help the DPRK to join international financial institutions. In order to become a member state of the IDA of the World Bank, the DPRK first needs to acquire member status from the IMF, which is infeasible without US consent. What is more, the DPRK has to meet three conditions to enter the IMF: transparent statistical system, financial status and monetary policy. Even if the regime successfully entered the international body, another grave task remains ahead to meet requirements including maintaining a stable currency and lifting restrictions on ordinary trade.

Borrowing from international financial bodies, such as the IMF, World Bank and ADB, requires following demanding economic policy programs. The size of loans depends on the success of the required economic and policy reforms. Given this, it is inevitable for the DPRK to seek reform and opening even in a limited way if it asks for financial help from international bodies. Lifting economic sanctions and admitting the DPRK into international bodies may not only give it an economic boost but also induce the regime to join international society.

According Most Favored Nation (MFN) status and Reaching Bilateral Trade Agreement with the DPRK

Once the nuclear problem is resolved, the US government should persuade Congress to take steps for lifting economic sanctions against the regime. In order to produce a noticeable effect from lifting of economic sanctions against the DPRK, these actions should be taken:

shelve application of the Jackson-Vanik amendment aimed at banning provision of MFN status and credit guarantees by state–owned financial institutions; (b) reach trade agreement between the US and the DPRK aimed at providing normal trade status; (c) secure “permanent normal trade status” for the DPRK and give the regime the benefit of Generalized System of Preference (GSP) that is being extended to developing countries.

Besides resolving nuclear problems, the DPRK needs to satisfy demands by Congress, such as improving the human rights of North Korean residents and abandoning all kinds of illegal behavior. China won a bilateral trade agreement in 1980, just a year after normalization with the US. By contrast, Vietnam began to benefit from MFN status and trade agreement in 2001, six years after establishing diplomatic relations with the US in 1995. Yet it is still excluded from the benefits of GSP. Given this, reaching a complete bilateral trade deal with the US requires the DPRK to meet several conditions proposed by the US Congress.

3. Apply a Comprehensive Denuclearization Approach

A Gradual Approach to third–phase Denuclearization

For successful third–phase denuclearization process, there is a need to present realistic objectives that can draw consensus from all of the countries involved in the Six–Party talks. As a top priority, the US needs to induce the DPRK to scrap its plutonium program and prevent the leak of nuclear materials to overseas countries. In addition, it needs to clarify that the nuclear problem may not eventually be resolved unless the DPRK presents its a clear position explanation of its on controversial nuclear connection with Syria and its Uranium Enrichment Program (EUP). The third phase may be subdivided into several steps.

First, verify the DPRK’s declaration on plutonium and other nuclear facilities following the verification protocol reached by the Six–Party talks. The verification should be perfect and accurate by using scientific methods. If necessary, the scope of verification should be extended to areas outside Yongbyon with the DPRK’s consent.

Second, the verified plutonium and dismantled nuclear facilities should be kept in the DPRK under international supervision. At the same time, weaponized plutonium should be split from nuclear device and be kept safe. Then discussion needs to be promoted over the DPRK’s subscription to NPT and IAEA as well as over the provision of a new light-water reactor. In order to facilitate progress of this phased denuclearization process, US and DPRK leaders might get together to hold a summit. Otherwise, leaders from China, the US and the two Koreas might convene a summit meeting. If discussion of this kind is promoted between the summit leaders in real terms, the chances will be high that the end of the Korean War will be declared, the US will provide security assurance in a written form and finally North Korean leader Kim Jong–Il can clarify his position on abandoning all nuclear weapons and programs.

Finally, the denuclearization plan enters a final stage when plutonium–based nuclear weapons are dismantled and are safely handled together with other nuclear materials and facilities. In a parallel move, the US and DPRK agree to establish full diplomatic relations and reach a Korean War Peace Agreement. A new light water reactor should be completed in parallel with the exit of nuclear materials and facilities. Until the nuclear reactor is completely built, equivalent economic and energy aid should be provided to the regime.

Set the CTR–NK Program in motion and utilize the Northeast Asian Security Forum

Experts in the US have strongly recommended Collaborative Threat Reduction as the only program capable of politically resolving issues around WMD of the DPRK. Only with DPRK cooperation, however, may the CTR NK prove successful. This has made it practically impossible to apply the program in the situation where the DPRK is isolated from the international community and remains hostile to the US.

For that reason, the US government needs to offer favorable conditions for the DPRK to accept the program for the successful dismantling of nuclear programs. If the US displays no intention of hostility towards the DPRK and takes a different approach to bilateral relations, the CTR NK program may be put into action in the final phase. Probably the watershed will lie in building a representative office in each other’s state to establish partial diplomatic relations and to provide written security assurance through a summit between the two countries.

Only when these conditions are met to a minimum extent will the DPRK be set free from complete isolation, marking the start of the CTR NK Program. However, US–DPRK agreement alone is not enough to propel the progress of the CTR NK Program. Perhaps global partnership involving two Koreas, China, the US, Russia and Japan should be built to add momentum. That is where the necessity of the Northeast Asian Security Forum arises within the framework of the Six–Party Talks. The Northeast Asian Security Forum may serve as an arena for discussing creation of a light–water reactor consortium that is needed for the DPRK to agree on NPT and IAEA. Apart from this, the forum may address issues regarding provision of nuclear fuel and management and safety of nuclear waste.

Support Conversion of Conventional Military Industry to Civilian Use

CTR could provide the DPRK an opportunity to pull itself from complete isolation and join the international community through cooperation with the US. In addition, the broadening of the application of the CTR NK to include conventional weapons will result in the reduction of DPRK military industry and the use of the limited natural resources in DPRK for peaceful purposes. Sharing the task with the US may be an effective way for the ROK to lead the effort to success.

Such a conversion program would also provide additional momentum to modernize the DPRK’s civilian economic environment. CTR may result in easing military tension and eventually can lead to moving the political weight from the military to economic bureaucrats and further to DPRK residents.

If the DPRK leadership is left to keep relying on the military and the military–based economy to maintain its political regime, easing military tension will remain a mere distant dream. In order to turn the plan into reality in strategic terms, the conversion could be more effective with economic cooperation in private sector. But the effort needs to be extended to developing an economic zone and financing conversion of DPRK military industry to civil use.

In this respect, the three economic cooperation projects in progress; (1) building Gaesong Industrial Complex, (2) bridging railways and (3) encouraging tourism to Mt. Geumkang,

have profound implications. In particular, building the Gaesong Industrial Complex

takes on significant meaning. In addition, a variety of economic cooperation projects agreed by the 10.4 South–North Summit Declaration in 2007 is considered strategically important in that the projects may motivate the DPRK to get out of the military-based economy just beyond the pursuit of economic interests.

4. Efforts to Improve DPRK Human Rights

(1) Prospects for Improving DPRK Human Rights

The Bush administration pointed to DPRK human rights on numerous occasions in the past 8 years. However, it did so as a means to criticize the DPRK regime rather than to pursue a consistent strategy for meaningful improvement in human rights. As a result, the Bush administration’s discussion of human rights prompted debates about human rights, but failed to contribute to meaningful improvement in human rights. The Bush administration took a pro–active approach to DPRK human rights issues in its early days; however, later its focus on human rights diminished as the administration shifted its priority to achieving progress on the denuclearization.

In October 2004, in the midst of heightened suspicions concerning uranium enrichment in the DPRK, the US Congress passed the North Korean Human Rights Act of 2004. The Act carries a symbolic value of raising the profile of North Korean human rights issue, but it failed to achieve any meaningful outcome because the Bush administration shifted its focus away from it during the second term. On October 7, 2008, The US Congress passed the North Korean Human Rights Reauthorization Act, which extended the Act of 2004 to 2012.

The Obama administration will need to establish a new basis for human rights policy by taking an approach aimed at effectively achieving real improvements in human rights through thoughtful assessment of current US human rights policy.

The following factors are emphatically recommended for the Obama administration to take into account in the formulation of its DPRK human rights policy.

First, a proactive willingness and cooperation for humanitarian aid coupled with the call for a guarantee for the fundamental right to life for North Koreans are required. Since the DPRK government is not able to guarantee its people’s right to life, demands must be made that it improve the situation by guaranteeing DPRK peoples’ right to undertake selling and buying activities in markets and farming for their own harvests while reducing excessive taxes and non–tax burdens.

Second, proper and full enforcement of relevant laws and modification and elimination of laws that are harmful to human rights must be required for improvements in DPRK human rights. It is common knowledge that most DPRK residents are faced with spontaneous inspections, control of communications, actions that lack sufficient legal basis, and guilt–by–association. Improvements in laws and systems must be induced for a more open and flexible civil society in DPRK, which lacks the most basic concept for human rights.

Third, efforts for improvement in DPRK human rights need to be implemented through a step–by–step approach in tandem with building a relationship based on trust through economic cooperation and normalization of relations. Demands for the DPRK government to unilaterally improve the human rights situation will not be helpful to North Korean people in any real sense because of the improbability that such an approach would to be accepted by the DPRK government, which is the abuser of human rights while at the same time the only party that can resolve the issue.

Fourth, all cooperation for development and non–humanitarian assistance shall be provided in a way that will induce the DPRK to change its policies towards opening. Proactive efforts will be necessary to persuade the DPRK government that improving human rights of North Koreans could provide an opportunity for the DPRK government to demonstrate its capacity to do the right thing as a sovereign and a rightful member of the international community rather than viewing it as a threat to the regime.

(2) US ROK Joint Efforts for Resettlement of DPRK defectors

The US has long expressed keen interest in the plight of DPRK defectors; however, other countries have shown complex reactions to the issue owing to geopolitical sensitivity in Northeast Asia. Mongolia and various Southeast Asian countries where many DPRK defectors have taken temporary refuges are reluctant to allow defectors’ resettlement in the US out of concern that such policy might encourage a large scale influx of DPRK defectors and its potential negative impact on their relations with DPRK, while China is guarding against the involvement of the US in the DPRK defector issue. The US embassies in relevant countries are also concerned over potential security issues in the event of substantial increases in the number of defectors from the DPRK, which currently does not have diplomatic relations with the US.

Countless North Koreans have crossed the China–DPRK border in search of food since the outbreak of food shortages in the late 1990s. The number was reported to have exceeded 300,000 at one point, then decreased substantially; but remains large. In the absence of a residency permit from the Chinese government, such defectors barely manage subsistence, while their children are not receiving education and some women defectors become the subject of human trafficking.

The majority of DPRK defectors prefer to resettle in the ROK because the ROK government provides all DPRK defectors with resettlement funds and vocational training under its resettlement program. In view of the likelihood that the Obama administration will grant refugee status to DPRK defectors, it is possible that more DPRK defectors will choose to resettle in the US. In preparation of such development, the US State Department needs to develop closer cooperation with the ROK government concerning information gathering and other aspects in order to ease the screening process for defectors who wish to resettle in the US.

The most pressing task at present is that diplomatic efforts should be directed to the maximum extent possible to improve living conditions of the defectors and to prevent forceful repatriation to the DPRK against the defectors’ will. Currently, children born to DPRK defectors who are illegal residents in various countries suffer from lack of basic civil rights as they suffer from lack of education and extreme poverty. Inspections, punishment, and forceful repatriation to the DPRK are continuing. In addition to petitioning the UNHCR to recognize DPRK defectors as refugee, the US and ROK governments need to develop support programs to help protect DPRK defectors. Various measures must be put in place to protect NK defectors in China, Russia, and Mongolia in preparation for a possible outflow of defectors from DPRK in massive scale.

The US and ROK governments need to cooperate to provide maximum convenience to DPRK defectors who wish to resettle in either the ROK or another country by allowing them to use the help of ROK and US embassies in other countries to the extent that such actions would not necessarily infringe the sovereign rights of the host countries. Efforts should be made also to obtain the understanding and cooperation from host countries to allow DPRK defectors who wish to travel to the ROK or the US for resettlement to travel with all related members who escaped from DPRK together.

III. US-ROK Cooperation for Institutionalized Peace in the Korean Peninsula

1. Pursuing the Tripartite Arms Control Agreement among the US, ROK and DPRK

(1) Progress in Easing Military Tensions in the Korean Peninsula

Europe took a gradual approach to arms control, first building military trust and then reducing arms. This approach was very successful in reducing tensions between eastern and western Europe during the Cold War era. This arms control model was possible in a comprehensive framework of the Helsinki Pact (1975) which included ‘humanitarian cooperation’ and ‘cooperation in other fields such as economy, environment, science and technology’.

The ROK and the DPRK have made continuous efforts to ease military tensions in the peninsula. Since the end of the Korean War in 1953, the two Koreas attempted to adopt the successful European arms control model. However, due to differences between the two sides, they failed to do so: the ROK wanted to take a gradual approach by building military trust first before adopting arms control; the DPRK insisted on reducing arms immediately. Although it did not yield tangible progress, an ‘Inter Korean Basic Agreement’ was adopted in December 1991 and took effect in February 1992. This is the first document agreed to by both sides since the signing of the Armistice. The Inter–Korean Basic Agreement consists of reconciliation, non–aggression, cooperation and exchange between the two Koreas. The ‘Non–aggression’ in Chapter 2 addresses large–scale base relocation, notification and control of military exercises, peaceful use of the De-Militarized Zone (DMZ), military personnel exchanges, information exchange, removal of WMD and attack capability, gradual disarmament and verification.

Since the inter–Korean summit meeting in 2000, only parts of the measures to build military trust and reduce weaponry have been implemented. The following are observations of how the two sides have pursued arms control since the first inter-Korean summit meeting.

Kim Dae-jung and Kim Jong-il in Pyongyang, June 15, 2000.

First, arms control between two sides was pursued in a way to provide security assurance for inter–Korean economic cooperation. The trust building measures both sides took were aimed at preventing accidental clashes in the Northern Limit Line (NLL), stopping slander, removing landmines in the DMZ and redeploying DPRK military forces to the rear of the Gaesong industrial complex and Gumgang Mountain projects.

Second, arms control initiatives for conventional weapons and WMD were pursued separately. South and North Korea implemented conventional weapons arms control while nuclear weapons were negotiated within the framework of the Six–Party Talks.

Third, the arms control negotiations on the Korean peninsula have so far taken place in the form of inter–Korean military talks within the context of the Armistice, therefore there is a weakness with respect to international laws. Yet, the current Armistice grants decision making authority only to the DPRK and the UN Command through USFK. Accordingly, humanitarian and material exchanges crossing the South Korean border are subject to UNC supervision pursuant to the Armistice, however, the missions stipulated in the Armistice are mostly delegated to South Korean forces. In order for South–North Korean arms control negotiations to reap substantial results consistent with international law, the two Koreas need to hold military meetings that engage the US.

(2) Signing the ‘Tripartite Arms Control Agreement’ as an Interim Step

If the negotiations over the DPRK’s nuclear issue can move toward a third phase, and relations between Pyongyang and Washington improve somewhat, discussions for a Korean Peace Agreement and establishment of diplomatic relations between the US and DPRK could begin. Also required are measures to provide military assurance. To this end, the two Koreas and the US will need to have a military meeting to sign the ‘Tripartite Arms Control Agreement’ that could include measures to provide military security assurance.

Such ‘Tripartite Arms Control Agreement’ can be considered an interim step before establishing a Korean Peace Agreement and diplomatic relations between the US and DPRK. It will include military trust building measures to be taken by the two Koreas and the United States and it will complement the provision of Chapter 2 concerning ‘Inter Korean Non aggression’ of the “Inter–Korean Basic Agreement” signed in 1991.

In addition, it will contain an appropriate level of disarmament measures. These trust building and arms reduction measures will ease military tensions on the Korean peninsula, persuading the DPRK to completely abandon its nuclear ambitions.

The ‘Tripartite Arms Control Agreement’ will stipulate that the Tripartite Military Committee (tentative) will replace the general–officer level dialogue between the UNC and Korean People’s Army (KPA) of DPRK, an improvised arrangement in lieu of the Military Armistice Committee (MAC) under the Armistice. This tripartite military committee will consist of representatives from the KPA, South Korean forces and USFK. The committee will hold military talks between the two Koreas or DPRK and the US or among the three parties.

This tripartite military meeting does not undermine existing inter–Korean military talks. Military talks designed to reduce military tensions will be held among all three parties. However, issues mainly affecting the two Koreas, the two parties will handle them through inter–Korea military talks. The US will be involved in issues which are directly related to its interests through three–party talks.

On behalf of the MAC, the Tripartite Military Committee can take over the responsibilities of maintaining the Armistice regime until the permanent peace agreement is signed. Not only that, the committee can implement measures to build military trust and reduce arms. One important trust building measure between the two Koreas will be pulling out forces from GP in the DMZ. Furthermore, in a bid to enhance military transparency, the DPRK should publish its defense white paper while the ROK should add content related to the USFK in its paper. The three parties also need to regularize bilateral or trilateral military talks, notify each other of military exercises, exchange observers groups, and limit the size of redeployed forces.

Arms reduction can be pursued alongside military trust building measures. For example, the two Koreas can restrict weapons used for sudden attacks, provide mutual security assurances, greatly reduce the number of forces, and restore and implement what is mentioned in the ‘Joint Declaration on Denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula’. In particular, it is important to convince the DPRK to join the international arms control and disarmament agreements on WMD, missiles and conventional weapons, so that the international community can closely monitor the DPRK.

2. Two-stage Process for Institutionalizing Peace in the Korean Peninsula

(1) Stage One: Summit Meeting to Liquidate Hostile Relations

Along with efforts to ease military tensions on the Korean peninsula, it is also necessary to transform the current Armistice to a permanent and more complete peace mechanism. If the Foreign Ministers’ meeting of the Six–Party Talks takes place, the ROK, the DPRK, the US and China can create a peace forum concerning the Korean peninsula to discuss how to replace the Armistice with a peace agreement that permanently guarantees peace in the Korean peninsula. Consultations to reduce military tensions in the Korean peninsula will take place in the tripartite military meeting, while the Korean peninsula peace forum will only address the conclusion of the peace agreement. Establishing institutionalized peace in the Korean peninsula is closely related to the progress on denuclearization of the Korean peninsula. The denuclearization process is expected to be very complex and difficult as it relates to the future of the DPRK regime. The Korean Peace Agreement stated in the 9.19 Joint Statement is likely to be reached in the final stage of denuclearization. The question is whether the DPRK will fully implement its denuclearization obligations with the goal of signing a Peace Agreement. It seems necessary to endeavor to remove anxieties of the DPRK on the way towards the Peace Agreement. To do so, the US president can consider the removal of hostile relations between the US and the DPRK, and the provision of written security assurance.

To liquidate hostile relations between the US and the DPRK originating in the Korean War (1950~53), the concerned parties need to reach consensus. The US and China as well as the ROK and China forged diplomatic relations in 1979 and 1992 respectively, thus liquidating hostile relations. The ROK and the DPRK also signed, though incomplete, the Inter–Korean Basic Agreement, which commits the two Koreas to build military trust, reduce arms and not to attack each other. Therefore, it is only the US and the DPRK which have not declared an end to hostility on the Korean peninsula.

Thus, it is necessary for the heads of the US and DPRK to meet and officially declare an end to hostile relations before moving from the Armistice to a peace agreement. To support this move, US President–elect Obama can offer the DPRK a written security assurance that the US will neither threaten nor attack the DPRK with nuclear or conventional weapons. In response to this, DPRK leader Kim, Jong–il could promise that his regime will completely abandon its nuclear ambitions during his term in power.

The summit meeting between Washington and Pyongyang would be perceived as a sign that the two countries would terminate hostile relations. It would have a political rather than legal implication. As such, the US–DPRK Summit, at the highest level, can provide momentum for the DPRK to make a decisive resolution to enter the final stage of abandoning its nuclear weapons.

Along with the US–DPRK Summit, a summit of four parties involving leaders from the US, ROK, DPRK and China can be also considered. The two Koreas have already recognized the necessity of ending the current Armistice and establishing a permanent peace system as stated in Clause 4 of the 10.4 Summit Declaration adopted during the 2nd round of the Summit Meeting in October 2007. They also agreed to work together to discuss how to declare the end of the Korean War in the three or four–party summit talks that involve leaders from countries directly related to this issue. If the four–party Summit can take place and issue a joint statement, it will be helpful to facilitate the progress in resolving the DPRK’s nuclear issues.

(2) Stage Two: Two Agreements to Institutionalize Peace

In order to guarantee institutionalized peace in the Korean peninsula, the following options can be considered: (a) Peace Agreement between the US and DPRK, (b) Inter–Korean Peace Agreement with endorsements by the US and China, (c) and Umbrella Agreement on Peace of the Korean Peninsula along with Inter–Korean Subordinated Agreement and the US–DPRK Subordinated Agreement. However, each option has limitations.

The first option excludes the ROK, although it is a directly related party, so the ROK would not accept it and it does not properly reflect the balance of power in the Northeast Asia. .

The second option has been strongly championed by the ROK government for a long time. In other words, the two Koreas could sign a peace agreement and the United States and China which are important parties of the Korean War either endorse or postscript it. This approach has the two Koreas as the directly concerned parties and reflects the dynamics of Northeast Asia. However, it lacks US security assurances for the DPRK, which the DPRK has demanded.

The third option was proposed by the US government in the four–party talks (ROK, DPRK, the US and China) in the late 1990s. Recently ROK and US government officials have formed a consensus around this proposal. This proposal suggests that ROK, DPRK, the US and China conclude an umbrella agreement. At the same time, the ROK and the DPRK as well as DPRK and the US sign a subordinated agreement. This method is very convincing in the sense that ROK participates in the process as a direct party and the current dynamics of Northeast Asia are reflected. But, its weakness is that it is not appropriate for resolving DPRK’s nuclear issue gradually.

Taking those aspects into consideration, we would like to suggest the following alternative: pursue two agreements with the goal of institutionalizing peace in the Korean peninsula, with one agreement signed by ROK and DPRK with the US and China participating as guarantors, and the other between the US and DPRK to normalize diplomatic relations. This reaffirms the principle of having the two Koreas lead the peace process in the Korean Peninsula while the US, through diplomatic relations, provides the DPRK with the comprehensive security assurances that it demands.

Under this scenario, the Korean War will be officially over and security assurance will be provided in writing through the US–DPRK Summit or the four-party Summit talks. Therefore, the agreement on normalizing diplomatic relations between Pyongyang and Washington will be good enough to provide a comprehensive security assurance. The bilateral agreement on normalizing diplomatic relations will address issues such as mutual respect for sovereignty, non–interference in the other country’s domestic affairs, peaceful resolution to disputes, non–aggression, and non–use of military power identical to the content of security assurances under a peace agreement. It would also define bilateral relations of the two countries and addresses issues related to protection of their nationals, the establishment of their missions, and mutual exchanges in the fields of science, technology and culture.

Under this proposal, the two Koreas will sign a Korean Peace Agreement based on the draft outlined in the Korean Peninsula Peace Forum. This can take place when the DPRK’s dismantlement activities are confirmed through the verification protocol and ambassador level diplomatic relations are forged between the US and DPRK. If the US–ROK agreement on the transfer of WOC (Wartime Operational Control) is executed as scheduled on April 17, 2012, the ROK will have WOC and there will be no more problems regarding its status as a party in the peace agreement. In addition to security assurances principles in the agreement on normalizing diplomatic relations, the Korean Peace Agreement should contain items termination the war, replacing the Armistice, establishing responsibility of the war and compensation, exchanges of Prisoners of War (POWs), repatriation, and drawing borders. This agreement could be deposited in the UN secretariat as a way to complete the process of establishing the peace regime on the Korean peninsula in line with international law.

3. Denuclearization, US-DPRK Diplomatic Relations and the Peace Agreement

With the improvement of bilateral relations between the DPRK and the US, the Cold War structure in the Korean peninsula could be quickly dismantled. If all goes well, it would be possible to rapidly establish diplomatic missions in Pyongyang and Washington. Both capitals have already secured sites to build their diplomatic missions when they pushed ahead with the establishment of a liaison office under the 1994 Agreed Framework (Geneva Agreement).

At that time, the DPRK was in the middle of a ‘March of Suffering’. And it was not confident enough to allow the Stars and Stripes to fly in public and American diplomats to drive around the streets of Pyongyang. That was why the DPRK reversed its words and gave up establishing a liaison office. However, when Kim Gye–kwan, Vice–Minister of Foreign Affairs of the DPRK visited New York in March 2007, he expressed hope for higher level diplomatic relations with Washington that will go beyond a liaison office. Therefore, if the concerned parties can enter the third phase after completing the implementation of the obligations under the 10.3 Agreement, it is feasible to establish diplomatic missions in Pyongyang and Washington in the near future.

The Obama administration should take a new approach in addressing the DPRK nuclear issue: it should resolve the issue by normalizing its relations with the DPRK instead of pursuing normalization on the condition of resolving the nuclear issue. Given the nature of the DPRK regime, where its leader, Kim, Jong–il, wields absolute power, Kim’s determination is critical to resolving the nuclear issue. Therefore, it is more practical and viable for the two leaders to first reach consensus and then discuss how to implement obligations instead of reaching small agreements en route to a larger agreement.

If the US–DPRK Summit could take place in 2009, the US could provide a written security assurance to the DPRK, the two leaders could begin partial bilateral relations, and at the same–time DPRK leader Kim Jong–il could promise to dismantle nuclear weapons, It would be possible to complete the dismantlement of DPRK nuclear weapons by 2012. By 2012, President–elect Obama’s first term would be coming to an end, ambassador level Diplomatic relations would be established, and a Peace Agreement between Pyongyang and Washington could be signed.

This new approach can also be applied to the inter–Korean relations. If the two Koreas repair their relations, the tripartite or four–party Summit talks can take place to declare an end to the Korean war as agreed in the 10.4 Summit Declaration. The third South–North Summit Meeting can also occur before or after the said meeting during the term of the Lee Myung–bak administration. If the leaders of the two Koreas, the US and China can adopt a declaration to end the Korean War, DPRK leader Kim Jong–il would be able to play a crucial role in making a decision on final and complete nuclear dismantlement.

When will the target year be for accomplishing denuclearization on the Korean peninsula? It might take a long time to complete the construction of a light water reactor and turn nuclear sites into green fields cleared of radioactive pollution after dismantlement. Confirming the amount of produced nuclear materials, dismantling weaponized nuclear materials and nuclear equipments in line with the verification protocol could take place in three to four years if negotiations go smoothly. Thus, the core activities of denuclearization can indeed be completed by 2012, which will be the last year of President Lee Myung–bak’s term and the first term of President-elect Barack Obama.

If the DPRK can complete core denuclearization activities by 2012, diplomatic relations between Pyongyang and Washington can be forged along with the signing of the Peace Agreement during the same period. This can ultimately lead to the complete dismantlement of the Cold War structure and the establishment of a peace regime on the Korean peninsula. In order for this roadmap to establish a peace regime on the Korean peninsula in four years, it will need strong backing from both the Korean and US governments.

IV. Joint Tasks of the US and ROK for Regional Security and Global Cooperation

1. Realignment of the US-ROK Alliance based on Shared Values

(1) Shared Values

The overall national advantages the US pursues would include expansion of democracy and freedom, secure stability between the strong world powers, prevention of emergence of regional superpower, prevention of proliferation of WMD, economic growth, and securing energy sources, etc. The national advantages pursued by the US in East Asia could be summarized as the safe and sound management of China Rising, utilization of growth momentum in East Asia, strengthening relations among allies in the region, resolution of regional conflicts regarding Taiwan and DPRK.

To secure worldwide as well as regional advantages, the most important element is US leadership in world affairs. However, the Bush Administration’s unilateral foreign affairs policies weakened the foundation of American leadership. Therefore the top priority foreign affairs tasks for the Obama Administration would be the restoration of international cooperation and recovery of American leadership based on democracy, international standards, and a multilateral approach.

The ROK and the US have different priorities in terms of their national advantages, but they also share a common approach toward the expansion of democracy, prevention of the emergence of a regional superpower, prevention of proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, and resolution of regional conflicts. In view of this, the ROK would actively support the efforts of the Obama Administration to restore US leadership and international cooperation.

However, the renewed efforts by the US would not be able to escape the limitations inherent in the alliance rooted in cold war ideology and based on opposition to common threats. It is because the threats of the 21st century go beyond traditional notions of the nation and extend to more complex, multifaceted threats. This is why the alliance between the ROK and the US should metamorphose from a cold war alliance to a 21st century alliance based on the pursuit of shared values. President–elect Obama emphasized that in order to restore US leadership, the US needs to strengthen the common security and global engagement. Accordingly, the ROK/US relationship should be redefined as, “Not What to Oppose But What to Aspire” for in common security.

The 21st century US–ROK alliance should advance from a “defensive alliance for the Korean Peninsula” against the common threats of the past to a “global alliance” that aspires for common values. The “common values” that both ROK and US aspire for should not mean unilateral promotion of arbitrarily values, but the advancement of common human values based on freedom, human rights, and democracy. In addition, these “common values” shared by the ROK and the US should not become the basis to shun other nations of different values, but should be used to construct a strong foundation for relations between the two countries.

(2) Realignment towards the 21st Century US–ROK Alliance

The realignment of the US–ROK alliance that began in 2003 has the purpose of changing the cold war style alliance to a forward looking 21st century one. At present, the realignment process is almost complete. In the US–ROK Summit meeting held in Kyungju in November 2005, the two countries defined the nature of the 21st century US–ROK alliance as that of a “comprehensive, dynamic and mutually beneficial relationship.” Based on this, the US–ROK Strategic Consultations for Allied Partnership (SCAP) was held, and it was agreed to promote the strategic flexibility of USFK (US Forces Korea) as well as US–ROK Free Trade Agreement (FTA).

At the US–ROK Summit Meeting held at Camp David in April 2008, the US–ROK alliance was newly defined as “a 21st century strategic alliance.” The ROK proposed to include “Value shared Alliance,” “Trust based Alliance,” and “Alliance for Peace Construction” as the contents of the 21st century alliance, but the Bush administration kept the stance of empathy in principle, and there were no agreed details. Therefore, the details of “the 21st Century Strategic Alliance” remain to be negotiated with the next administration. At the start of the Obama Administration, an overall review of the US–ROK alliance is proposed while both countries faithfully implement the existing agreements related to realignment of the alliance. “The Future Vision of the 21st Century US–ROK Alliance” should be based on this overall review. “The Future Vision of the 21st Century US–ROK Alliance” should focus on dialogue and agreement on broad issues and directions such as: perspectives on the DPRK and China; a Security Plan for Northeast Asia and East Asia; and a framework for cooperation for the war against terrorism, rather than dealing with current issues.

The 21st Century US–ROK Alliance should be based on common values, and should participate and contribute to the security challenges faced by the international community. It should be an alliance in which the ROK’s role is expanded and strengthened by active support for and participation by the ROK government in the US’s global war against terrorism.

In order to achieve this, the US–ROK Alliance needs to be reconstructed first. The transfer of the Wartime Operational Control (WOC) which is scheduled for April 17, 2012 to the ROK army and the issue of the new order of the military command should be pursued in conjunction with the overall review of the USROK Alliance. It is recommended that the issues currently under negotiations, i.e., the shrinking of USROK defense expenses, relocation of the USFK bases, and environmental corrective actions are promptly settled for mutual benefits.

2. Regional Security Cooperation for Peace and Stability in East Asia

(1) Objectives and Functions of the Northeast Asia Security Forum

The Six Party Talks, created from the perspective of a functional multilateralism, has seen its objectives broadened to include normalization of the US–DPRK relations, normalization of DPRK–Japan relations, and establishment of a Northeast Asia Peace and Security System. It is anticipated that once the second phase of denuclearization is completed in the 6 Party Talks, a minister level meeting would be convened to propose a Northeast Asia Security Forum, based on the groundwork of working groups. Security talks among the Northeast Asian countries would have a supporting role to the traditional bilateral alliances of the US.

The Six-party talks

For successful operation of the Northeast Asia Security Forum, participating countries would have to first agree on the guiding principles. It would be possible to devise the guiding principles based on the three principles declared in the “9.19 Joint Statement.” These three principles are: first, a passive security guaranty offered to the countries with no nuclear weapons; second, faithful adherence to the goals and principles of UN Charters (peaceful settlement of conflicts, respect for national sovereignty, territorial integrity, non use of force, no interference in domestic politics, etc.) and recognized standards of international relations; third, promotion of bilateral and/or multilateral economic cooperation in the areas of energy, trade and investment. To these, it would be possible to add the denuclearization of the DPRK and nonproliferation of nuclear arms in other existing non-nuclear countries.

This Northeast Asia Security Forum would have the following two functions. In the medium term, the first function would be to become the implementing entity of the CTR NK in the final settlement of DPRK nuclear issues, and the second function would be (for the Forum) to develop into and become the foundation for a long–term permanent security council in Northeast Asia. As mentioned earlier, the Northeast Asia Security Forum would be able to carry out the functions of an international council for DPRK denuclearization and the Northeast Asia Security Forum would not only be able to prevent the transfer of nuclear material or techniques through the CTR NK program but also to maintain effective retaliation methods and assure security. Its members would be the 6 Party Talks members, the DPRK, ROK, US, Japan, China, and Russia, and could include EU countries, Australia, and New Zealand as observers of the Northeast Asia Security Forum.

In the long term, the Northeast Asia Security Forum would give a birth to a permanent Northeast Asia Security Council. There is a need to have a framework other than the bilateral agreement or summit meetings among the countries in the region. For the successful formation, maintenance, and operation of the Northeast Asia Security Council, it is important to have China’s constructive role. There is also a need to recommend that Japan increase its efforts to remove potential conflicts with China, Russia, and DPRK.

(2) Efforts to Create the Northeast Asia Security Council

The Northeast Asia Security Council should be combined with the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) and should be developed to encompass the East Asia Security Community. The ARF, centered in South East Asia, is at an early stage of organization compared to the Organization of Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), and the three developmental phases ARF established for itself, i.e., Trust Building Preventive Diplomacy Resolution of Conflicts, and it has yet to operate in the phase of Preventive Diplomacy. Nevertheless, it is the only security forum in the East Asia Region and as such has great significance and importance.

When the existing ARF and the yet to be created Northeast Asia Security Council become one entity, the East Asia Security Community, the anticipated effects are these: First, the ARF has accumulated, since its establishment in July 1994, many meaningful precedents of dialogue and cooperation among the countries in Southeast Asia. If the Northeast Asia Security Council, which has its origin in the 6–Party Talks (a functional and temporary mechanism of dialogue by multiple countries), draws on the accumulated experiences of the ARF, which has grown into a mechanism of dialogue amongst regional countries, it would generate synergies and would be able to develop into the East Asia Security Community.

Second, beyond the issue of denuclearization in the Korean Peninsula, a common interest of 6–Party Talks members, the issues that require pan–regional cooperation between the countries of Southeast and Northeast Asia are increasing. These are the control of terrorism, proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, organized crime, human trafficking, drug smuggling, epidemic diseases, contamination of the environment, earthquakes and Tsunamis.

Third, the ARF is centered in ASEAN, a negotiating body of small and medium countries in Southeast Asia, and it values the consultation and consensus of participating countries. Because of its loose organization and delay in decision–making, it has shown limitations in dealing with emergency issues in the region. When combined with the Northeast Asia Security Council, where four world powers participate, it would have the practical ability needed for a security community.

However, ARF is at an early phase, and it might take a long time to launch the Northeast Asia Security Community. Therefore, there is a high possibility that the establishment of the Northeast Asia Security Community would become a task that continues to be pursued even after the Obama Administration.

(1.) Global Cooperation for the War against Terrorism

The Quadrennial Defense Review 2006 stated the victory over a long war against violent extremists as the strategic goal of the US Department of Defense. However, the US Defense Strategic Report published in 2008 defines the long war against terrorism as a more complex, spontaneous, and multilevel conflict than that against communism during the cold war, and emphasized the need for cooperation with other countries in order to eliminate the accommodating environment as important as the military strategy against the extremists.

The ROK, which aspires to a 21st century global alliance based on common values, needs to actively cooperate with the US in the global war against terrorism led by the US. The ROK should be able to agree readily with the objectives and methodology of the global war against terrorism particularly in view of the fact that the new US administration will value the importance of “soft power” instead of relying solely on “hard power”.

In October 2001, the US launched its war against terrorism in Afghanistan under the code name “Operation Eternal Freedom” following the 9.11 terror event. It launched also “Operation Iraqi Freedom” aimed at elimination of terror threats and prevention of the spread of weapons of mass destruction. The Bush administration asked the ROK to join the war against terrorism. In response, the ROK dispatched a medical support unit and construction and engineering teams to Afghanistan and sent non-combat support including medical assistance, technical training, and reconstruction work.

First, cooperation between the US and ROK in the area of “hard power” is possible. It is likely that the new US administration will renew its request for support from the ROK in conjunction with its decision to start withdrawing troops from Iraq and concentrate its efforts on Afghanistan. This was indicated by President Bush, who raised the matter of sending troops to Afghanistan during the August 5–6, 2008 US–ROK summit meeting. The possibility that the US would request that the ROK send combat troops to Afghanistan cannot be ruled out especially in the event that sending NATO troops mobilized by NATO member countries becomes difficult. The possibility of sending ROK troops should remain open for discussion. ROK troops should be able to participate actively in non-combat activities with consensus of ROK people within the international laws and rules of engagement such as the UN Security Council’s resolution, because the ROK should recognize the need to provide help to countries that suffer from failure of their policies and lack of security of their people. However, it should be noted that dispatching troops solely in response to the US request and ignoring international legal basis and procedures could involve the risk of considerably damaging US–ROK bilateral relations.