Wada Haruki

Translation by Gavan McCormack

Since the Six Party Beijing Agreement on North Korea of 13 February 2007, optimism has spread on all fronts save one – Japan. For the Abe government, nuclear weapons constitute only part of the North Korea problem. Indeed, as Wada Haruki notes below, for the Japanese government it is not nuclear weapons but the abduction problem that constitutes “the most important problem our country faces.”

Former US Deputy Secretary of State Richard Armitage recently commented to a Korean newspaper (Hankyoreh, 18 February) that it might take more than a decade to achieve the denuclearization of North Korea, and raised the possibility of the US having to “sit down with Japan and prepare for the possibility that North Korea will remain in possession of a certain number of nuclear weapons even as the [Korean] peninsula comes slowly together for some sort of unification.” The well-informed Russian observer Georgy Bulychev also suggested a 10-year scenario in writing for Japan Focus.

The shift in policy on the part of the Bush administration since the North Korean nuclear test, opening the possibility of accommodation with North Korea, is having a seismic shock effect on Japan that could prove comparable to the shock of Nixon’s China policy shift of three decades ago. With Bush now requiring Japan to negotiate normalization, Abe’s North Korea “containment policy” is in disarray, as the Asahi Shimbun commented on 15 February. Nobody in Japan, least of all its Prime Minister, is ready for the sort of “sitting down” that Richard Armitage suggests. Confusion and anger spreads, and some political instability may perhaps be expected.

The following comment, reviewing North Korea’s road to developing atomic weapons in the face of the US threat, and in the context of the deepening relationships in recent decades between the Soviet Union and China on the one hand and South Korea on the other, was written by leading Japanese scholar, critic, and North Korea expert, Wada Haruki, for the Spring 2007 issue of the Korean journal Historical Critique (Yoksa Pip’yong), Seoul, Spring 2007, No. 78). Gavan McCormack translates and slightly abridges it here from Wada’s original Japanese text. (GMcC)

After North Korea conducted its nuclear test, the 10 October (2006) issue of Rodong Sinmun reported it in column 18 of page 3, as if to say – why the fuss, we said we possessed nuclear weapons and the conduct of a nuclear test is nothing special. The rest of the paper carried details of the celebrations of the 80th anniversary of the foundation of the Down with Imperialism Union.

It showed that the North Koreans themselves were relaxed and that there was nothing out of the ordinary. Of course it also concealed the magnitude of their effort to be able to conduct the nuclear test. But we could see that they were sufficiently in control of things to be able to determine the attitude they would present to the outside world. In Japan, by contrast, the media was full of reports suggesting that North Korea had gone crazy.

Historical Background

North Korea has long been exposed to the threat of American nuclear weapons. It is well known that at the time of the Korean War the US gave serious consideration to the use of such weapons. North Korea fought with the endorsement of the Soviet Union, and with its material aid and the participation of Soviet pilots, but the situation was such that, had the US used nuclear weapons, Soviet nuclear retaliation would have been out of the question. As for China, its forces fought with and gave very considerable aid to North Korea but China did not possess nuclear weapons. In other words, Chinese forces without nuclear weapons fought against American forces that both had them and might well have used them. In the end, the US held back from the use of nuclear weapons, and a ceasefire was reached.

Under this ceasefire, Chinese forces remained in North Korea until 1958. During this period, there were various negotiations between the Soviet Union and China over the question of Chinese nuclear weapons development. In the end, in the context of Sino-Soviet confrontation, China from 1960 undertook to develop nuclear weapons independently. After both the Soviet Union and China in 1956 failed in their plans to replace Kim Il Sung as North Korean leader, from 1961, taking an independent path, North Korea concluded mutual cooperation agreements with both. As a result, North Korea came under the Soviet nuclear umbrella. From 1964 China too came to possess nuclear weapons.

After the ceasefire ending the Korean War, North Korea gave up the idea of unification by force of arms but during the 1960s, stimulated by the course of events in Vietnam, it adopted a line of seeking unification through support for armed guerrilla movements in South Korea. In 1968 it sent guerrillas on a raid to the Blue House and captured the American warship, Pueblo. This North Korea action alarmed the Soviet Union. As the Vietnam War turned into a quagmire, the US responded by making concessions. The North Korean guerrilla incursions were also rejected by the South Korean people. North Korea’s unification-by-arms line ended as a whole in defeat, and for the next 25 years there was no possibility of war breaking out on the Korean peninsula. Because there was no risk of war on the Korean peninsula, the South Korean army was able to dispatch a large force to participate in the Vietnam War.

Watching China’s independent nuclear development, from the 1960s North Korea was interested in nuclear development, and in the context of its adoption of Juche Ideology and its aim at a “unique ideological system,” “a Suryong (leader) system,” and a “partisan state,” the idea of nuclear weapons as the pillar of autonomous defense came easily. However, even though there may have been such an idea, and research may have begun, the path to success in nuclear development must have seemed remote.

Korean monument to Sure Victory

In the 1980s, South Korea achieved democratization, gained economic power, stabilized its system, and successfully staged the 1988 Olympics. The pressure it exerted on North Korea reached a peak. North Korea’s response seems to have been the destruction of the KAL airliner in 1987. When the Soviet Union proceeded to open diplomatic relations with South Korea, it meant that North Korea was deprived of its nuclear umbrella protection. On 2 September 1990, North Korean Foreign Minister Kim Yong-Nam told visiting Soviet Foreign Minister Shevardnadze that since the Soviet-North Korean treaty no longer had any substance, “henceforth we will have to take steps to supply ourselves with the few weapons that till now we have relied on the alliance for.” (Asahi Shimbun, 1 January 1991)

To cope with the multi-layered crisis it faced, North Korea seems to have decided simultaneously to begin negotiations for normalizing relations with Japan and to take its first serious steps on the path of nuclear development. Having lost the nuclear umbrella, it must have decided that nuclear weapons would have to constitute the pillar of national defense. Nuclear weapons, which would be aimed at South Korea, were seen as indispensable to make up for the inability to maintain the balance in conventional weapons due to economic collapse. When North Korea blocked the International Atomic Energy Agency inspectors and then withdrew from the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, a decisive confrontation with the US ensued. In 1993-4, relations moved to the brink of war, for the first time since the ceasefire ending the Korean War. Since the US could not fight such a war without the use of Japan as a base and Japan’s full cooperation, it demanded that Japan adopt an effective crisis cooperation system. In the late 1990s, the Joint Security system was redefined, and various laws adopted in Japan for dealing with “regional contingencies” and “emergencies.”

However, the 1994 crisis was dramatically resolved by the Carter visit to North Korea and his meeting with Kim Il Sung. The “Agreed Framework” was reached between the US and North Korea soon thereafter. South-North talks were also promised but in the wake of Kim Il Sung’s sudden death, because of the policies of South Korean leader Kim Young Sam, South-North relations suddenly grew extremely tense. That influence also reached Japan and even the Murayama Tomiichi government was unable to reopen Japan-North Korea negotiations.

The Kim Dae Jung government came to power in South Korea in 1998 seeking to open South-North relations under the “Sunshine” policy. The realization of the South-North summit of 2000 brought great change. US-North Korea relations were also affected. North Korea’s Number Two, Choe Myong-rok, visited Washington and Secretary of State Madeleine Albright visited North Korea. The moment was reached when a visit by President Clinton to North Korea might have decisively pushed the relationship towards normalization. That visit did not, however, materialize.

Kim Dae Jung and Kim Jong Il at 2000 summit in Pyongyang

With the victory of the Republican candidate, George W. Bush, in the presidential election, the situation took a sudden turn for the worse. Bush showed personal hostility towards Kim Jong Il, and referred to North Korea as a member of the “Axis of Evil.” After 9/11 he went to war in Afghanistan and in Iraq. North Korea began to look for ways to pursue nuclear weapons development outside of the Agreed Framework which was in shambles.

Major steps were taken towards normalization of relations with Japan with the 2002 Koizumi visit to North Korea and the signing of the Japan-North Korea Pyongyang Declaration. In response, the US insisted that North Korea was pursuing a uranium enrichment program and scrapped the Agreed Framework. However, even though the US was refusing direct negotiations and North Korea was pursuing its nuclear development, from April 2003 the Six Party talks began. These talks culminated in the September 2005 joint statement spelling out the denuclearization of the Korean peninsula and a future of peace and cooperation in Northeast Asia. However, just before that agreement, the US Treasury froze North Korean accounts in the Banca Delta Asia in Macao, accusing North Korea of counterfeit dollar manufacture. North Korea said that, unless those financial sanctions were rescinded, it would not return to the Six Party Talks. Instead, it sought direct negotiations with the US, which the US refused. In that context, North Korea carried out its succession of missile tests on 5 July and its nuclear test on 8 October 2006.

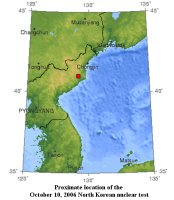

Map showing location of North

Korean nuclear test

From this sequence of events, North Korea conducted its nuclear weapon program with the US in mind, while at the same time it was striving for normalization of relations with Japan. Even at the time when it reached the agreement with the US to stop nuclear development, we can see that it did not completely abandon the possibility of nuclear weapon development, thinking of it as perhaps a kind of insurance. The Bush administration’s policies threatened North Korea, but were unable to stop it from possessing nuclear weapons.

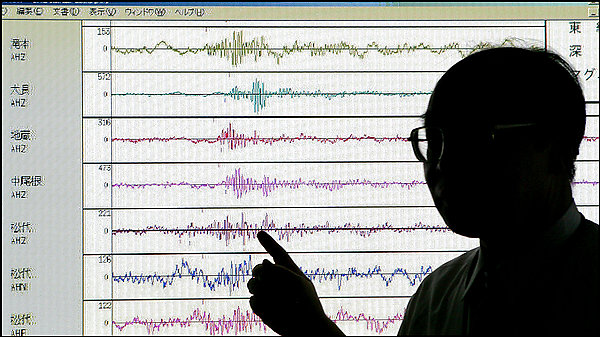

Japanese meteorological agency official points to seismic indicator of 4.9 following the North Korean October nuclear test

Current Position

Why is North Korea now manufacturing and possessing nuclear weapons? North Korea explains that its possession of nuclear weapons is the lesson it draws from the war in Iraq. In other words, it sees the Saddam Hussein government in Iraq as having been overthrown by US forces because it did not have nuclear weapons. What does this mean?

We need to pay attention to the situation at the beginning of the Iraq war. It began as an American terrorist stratagem to kill Saddam Hussein. On 18 March 2002, President Bush issued a final ultimatum for Saddam Hussein and his sons to leave Iraq within 48 hours. On 19 March, before the ultimatum expired, the US destroyed a Baghdad restaurant by pinpoint missile attack. It was a terrorist attack based on intelligence that Hussein and his advisers were in that restaurant. Had they been able to kill Hussein, war might have been unnecessary, but this terror measure failed.

North Korea must have watched these events carefully. The US had several times said it was not thinking of military measures against North Korea. But would it not be sensible to think that they might also have been planning to kill Kim Jong Il, and that any intelligence to the effect that North Korea was proliferating nuclear materials or selling to terrorists would have served as a pretext for carrying this out? Presumably because it sensed this, North Korea repeatedly said that it did not intend to proliferate nuclear weapons but it most likely also secretly sent messages to the US saying that they would respond by using nuclear weapons if any attempt was made to kill Kim Jong Il. The spirit of “Defend the Suryong [leader] to the death” has long been cultivated. The slogan of “defend with our lives the respected supreme commander Comrade Kim Jong Il as the brain of the revolution,” is the most fundamental slogan of the “military first” [songun] policy. And one can easily understand that nuclear weapons came to be seen as the tool for the resolute defense of Kim Jong Il’s life. If North Korea were to use nuclear weapons, it would be against South Korea and Japan. The target would of course be US bases in South Korea and Japan, but North Korea is unlikely to be capable of pin-point attack, and anyway, in the event of any nuclear attack, the US would respond with nuclear counter-attack in the next moment, reducing North Korea to a smoldering wasteland. For North Korea nuclear weapons are really weapons of self-destruction. We recall that along with “the spirit of readiness to die in defense of the leader (suryong)” North Korea also emphasizes the “blow oneself up spirit.”

For this reason, in the name of all the people of Northeast Asia, we must insist that any American operation to kill Kim Jong Il be nipped in the bud, while at the same time we absolutely oppose North Korean nuclear weapons.

One additional consideration for North Korea is that possession of nuclear weapons is a diplomatic tool for seeking direct negotiations with the US. In this sense, the North Korean nuclear test had an effect on the US mid-term Democratic victory and forced Bush into a corner. Not only did Bush’s Iraq policy have to be revised but his North Korea policy too was affected, and the call for direct talks gathered strength. The US agreed to set up a working group on easing the financial sanctions, with a view to reopening the Six Party talks, and it agreed in practice to bilateral negotiations. Partial moves towards lifting the freeze on North Korean funds in the BDA were reported. It would appear that the US was intent on selling to North Korea the idea of “early harvest.”

If all of this was the result of the nuclear test, then it was clear that the nuclear card was really a powerful instrument of North Korean diplomacy. The US could not ignore a North Korea that not only declared that it had nuclear weapons but had given a practical demonstration of them. If North Korea’s nuclear weapons were thus an instrument of diplomacy, then it should be possible to respond diplomatically to set about changing relations between North Korea and the other countries.

Put differently, North Korea’s nuclear weapons have two sides, the “in itself ” component and the diplomatic tool component, and it becomes desirable to widen as much as possible the diplomatic tool component while constraining as much as possible the “in itself” component.

The Ghost of Regime Change Theory

The policy of regime change by non-military, non-terror means constitutes an additional problem. Such thinking exists both within the Bush administration and in the Japanese Abe government. The US tried to achieve this goal by using financial sanctions and human rights as levers.

It is a fact that the UN Security Council resolution for sanctions, led by Japan and the US but supported also by China, Russia and South Korea, functioned as pressure on North Korea. However, there are limits to such pressure. As the US revises its policy on North Korea, it is the Japanese government that, at the present juncture, is left behind.

Since Abe became Prime Minister because of his hard-line stance on the abductions, the resolution of the abductions is the number one problem for his cabinet. All members of cabinet are also members of the “Abduction Problem Headquarters” that he set up. From 10 to 16 December 2006, the first “North Korean Human Rights Violations Week” was conducted under a law passed the previous June. On its opening day, all six national newspapers carried a half page advertisement under a photograph of Prime Minister Abe as head of the Abduction Problems Headquarters and the heading, “Abduction Problem – Striving Earnestly for the Return to Japan of all the Abductees.” It included the sentence, “Taking the stance that all the abductees are alive, our country … is exerting every effort to secure the return of all the victims …” It is a formulation that takes for granted that North Korea is lying. It also says, “We strongly demand that North Korea immediately send back to Japan all the abductees. The abduction problem is the most important problem our country faces.” If resolution of the abduction problem means return of all the abduction victims, then the abduction problem cannot be solved other than by the overthrow of the Kim Il Song government. Adrift in the currents of regime change theory, Japan has abandoned diplomacy.

Japanese government policies and the mood of its media constitute a major obstacle to resolution of the North Korean nuclear problem, and along with the North Korean government’s policies, constitute a serious problem for Northeast Asia.

Wada Haruki is professor emeritus, Institute of Social Science, Tokyo University and a specialist on Russia, Korea, and the Korean War.

Posted at Japan Focus on March 10, 2006.

Gavan McCormack, a Japan Focus coordinator, is the author of Target North Korea. Pushing North Korea to the Brink of Nuclear Catastrophe.

See also Gavan McCormack, A Denuclearization Deal in Beijing: The Prospect of Ending the 20th Century in East Asia