Cold Comfort: The Japan Lobby Blocks Congressional Resolution on World War II Sex Slaves

By Ken Silverstein

Introduction by Alexis Dudden

Journalist Ken Silverstein recently published a piece at Harpers.org called “Cold Comfort: the Japan Lobby Blocks Resolution on WWII Sex Slaves” (October 5, 2006), which Bryan Bender of the Boston Globe elaborated on in an article headlined “U.S. Congress backs off rebuke of wartime Japan” (October 15, 2006). What we know from both pieces is that, for the past six months, the government of Japan has paid hefty fees ($60,000 a month) to the Washington firm of Hogan & Hartson to prevent House Resolution 759 from reaching a vote before the House adjourned on October 13, almost guaranteeing that, once again, American legislative attempts to hold the Japanese government responsible for Japan’s actions during the Second World War have failed. Former long-term Illinois Republican and House minority leader Bob Michel worked as Japan’s main mouthpiece. Yet, as Silverstein contends, Michel “is only the most prominent of a small gang of lobbyists which Japan retains to handle World War II issues.”

Last April, Illinois Democrat Lane Evans and New Jersey Republican Chris Smith introduced a non-binding resolution urging Japan to formally “acknowledge and accept full responsibility” for what is commonly known as the “comfort women” issue. As is now well known, between the early 1930s and 1945, the Japanese government sponsored the systematic enslavement of as many as 80,000 to 200,000 women and girls from throughout Asia and the Pacific in brothels for use by Japanese soldiers and civilians, many of them directly affiliated with the military. Though not related to the House effort, throughout 2006 the global movement to stop violence against women and girls known as V-Day—an offshoot of American playwright Eve Ensler’s phenomenon The Vagina Monologues, which is a play, and the women’s activism it spawned—made the surviving comfort women its “spotlight” group for the year, speaking to the impact their history continues to have on so many. The women of Iraq held the “spotlight” position in 2005.

House Resolution 759 was not the first attempt by U.S. lawmakers to draw attention to and seek apology for Japan’s historical crimes. It was, however, the first to have bipartisan support from the start. This generated hope for success among its chief backers: various Korean American and human rights groups. Although the measure lost some of its steam through the summer months, it gained rapid momentum in late summer when Illinois Republican and Pacific theater veteran Henry Hyde returned from an “emotional trip” to Asia, including Korea, and put the Resolution up for immediate consideration before the House International Relations Committee, which he chairs. The measure cleared the Committee unanimously on September 13. The momentum led many to believe that the next step of a simple voice vote in the House was a done deal, not least because, as Silverstein writes, “This shouldn’t be controversial, since the historical facts are clear.” Indeed, the Japanese government was forced to acknowledge the basic facts of the system in the face of archival evidence produced by historians and supported an unofficial reparations program of redress. It has adamantly refused, however, to publicly fund a program that would formally apologize and lay to rest the historic issue.

HenryHyde

Despite the Committee’s recommendation and ample evidence documenting the Japanese government and military’s historical involvement with the enslavement and torture of scores of thousands, two troubling issues make the statement of any official American position on the comfort women deeply problematic. One, to which we return below, is the politics of the U.S.-Japan relationship. The other is the question of America’s own historical record of military-related prostitution during the Second World War and subsequent wars—and in the shadows of a worldwide network of military bases, including those in Korea and Japan.

Japanese commentators have leapt to point to American hypocrisy. An editorial in the Yomiuri on October 16 alludes to American legislators’ “lack of balance,” shrewdly diverting attention away from Japan’s wartime record to Japan under American occupation. As the editorial explains—and as Yuki Tanaka, John Dower and Mike Molasky have long pointed out in their respective books—“there were brothels for officers and soldiers of the Allied Occupation. The facilities were built at the initiative of the Japanese government, worried about sexual violence by the officers and soldiers against Japanese women. But there were also facilities that were set up under the order of the Allied Occupation. Did U.S. House members who approved the resolution carefully examine this fact?”

Equating American wartime and military base brothels and Japanese sexual slavery is not, however, the main concern of the Yomiuri editorial. The paper goes on to castigate Tokyo’s Foreign Ministry for even allowing “the House committee to submit the resolution to the full House for debate. It must never repeat such a mistake.” Such hair-raising rhetoric is likely not to disappear and is arguably more revealing about changes to come in the parameters of Japanese political debate over ensuing months.

It is interesting to note that American embassy officials in Tokyo gave Secretary of State Condoleeza Rice a copy of the Yomiuri editorial when she arrived in Tokyo on October 18. However, given the fact that Rice’s latest trip on behalf of the Bush administration centers on enlisting Japanese cash and support for isolating North Korea, there is little reason to anticipate that the Secretary of State will wish to take up historical issues of justice for Asian women victims of violence in war.

The ability to pigeonhole the comfort woman resolution in the Congress continues a perfect record of success for the combined forces of the U.S. State Department and the Japan Lobby, which, since the 1951 San Francisco Treaty, have protected the Japanese government from pressures to accept responsibility for its war crimes and provide reparations for its victims. As Kinue Tokudome and other researchers have shown, that record extended to the State Department’s blocking of efforts by American survivors of forced labor in Japanese POW camps to obtain justice in U.S. courts. The surviving American former POWs continue to seek legislative redress in Congress, in the face of the same combination of Japan Lobby and State Department that buried the Asian comfort women resolution.

Here is Ken Silverstein’s article of October 5, 2006.

Even as top congressional Republicans were protecting Mark Foley from exposure for soliciting teen pages, they were simultaneously helping Japan cover up its past record of institutionalized rape and sexual enslavement of Asian women. The Japanese cause was greatly aided by Bob Michel, a highly paid lobbyist and former G.O.P. congressman with close ties to the party’s leadership.

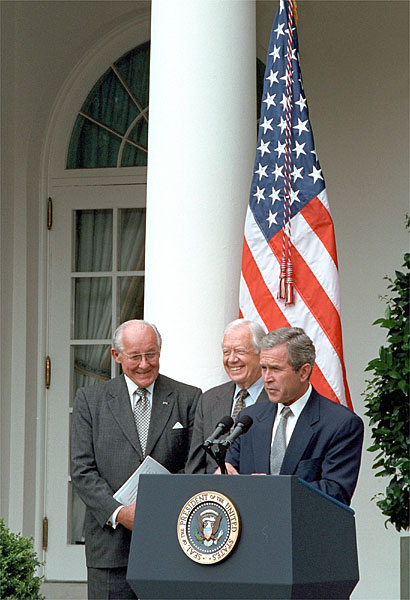

Bob Michel with Jimmy Carter and George W. Bush

For the past seven years, a coalition of Korean-American, human rights, and religious groups have been pressuring congress to urge Japan to accept responsibility for forcing women and girls into sexual slavery during the World War II era. This shouldn’t be terribly controversial, since the historical facts are clear.

Beginning in the 1930s, Japan rounded up as many as 200,000 women and girls, mostly from Korea, China, and the Philippines, and forced them to serve as prostitutes for its soldiers in order to increase troop “morale.” The Japanese called these sex slaves “comfort women”; many were raped and beaten, and some were killed after they acquired sexually transmitted diseases or became “overworked.” Some of the women were so humiliated that they never returned to their homes after the war, and many of those who did kept quiet about their experiences.

Japan long insisted that the comfort women were willing prostitutes and only acknowledged the sex slavery system in 1993 after documents discovered in the Japanese Army archives proved its true nature. The Japanese government backed the establishment of the quasi-governmental Asian Comfort Woman Fund in the mid-1990s but it has refused to offer direct compensation. Many of the women and their families have refused to accept money from the fund because they say Japan has never taken responsibility for its actions.

Japan has always been able to block attempts to pass a congressional resolution on the exploitation of comfort women, partly because it runs a lavishly-funded Beltway lobbying operation. The Bush Administration has quietly assisted in attempts to block a resolution on comfort women. According to Mindy Kotler, the director of Asia Policy Point, a research center on Japan and northeast Asia, the Administration views Japan as the key regional bulwark against an emerging Chinese regime that may be hostile to the United States in the future. “The administration wants Japan to be a central part of America’s Asian security architecture—above Australia, India, and the British Navy,” she said. “Any issue that the Japanese have defined as disturbing has been shunted aside to ensure that nothing upsets the alliance with Japan—and I mean nothing, whether it’s a trade dispute or taking responsibility for the comfort women.”

Not long ago, though, it looked like a measure had a decent chance of getting through. The coalition pressing Congress on the issue had traditionally sought to win a concurrent resolution, which must be approved by both chambers. This year the coalition worked for a resolution in only the House, and one was finally brought forth in April by Democrat Lane Evans of Illinois and Republican Chris Smith of New Jersey. The non-binding measure called on Japan to formally “acknowledge and accept full responsibility” for the sexual enslavement of “comfort women” and to stop denying its crimes—for example, by stripping mention of the topic from school textbooks.

The resolution was referred to the International Relations Committee and quickly gained co-sponsors, which alarmed the Japanese government. Enter Bob Michel, a top Washington lobbyist with Hogan & Hartson and a thirty-eight-year House member from Illinois, who served fourteen years as the G.O.P.’s minority leader. The Japanese government pays his firm about $60,000 per month to lobby on the sole matter of historical issues related to World War II, which also include claims concerning Japan’s vile abuses of American P.O.W.s, including the use of slave labor. (Michel, incidentally, is only the most prominent of a small gang of lobbyists which Japan retains to handle World War II issues.)

Korean Comfort Women Protest

Michel, I’m told, met in late May with Illinois Congressman Henry Hyde, chairman of the International Relations Committee. He told Hyde that passing the resolution would be crippling blow to America’s alliance with Japan and reminded the congressman that Japan’s sexual enslavement of several hundred thousand women had taken place some sixty years earlier—bygones should be bygones. Japan’s then–Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi had already announced that he’d be visiting the United States at the end of June (when he would visit Graceland with President Bush and sing “Love Me Tender” in the Jungle Room) and Michel argued further that it would be embarrassing to Japan if the measure was approved around that time. “The whole deal came to a stop,” says a source who was working to pass the measure. “I’ve never seen anything like it. We had a lot of momentum and suddenly it was just dead.”

But the groups working on the issue kept at it and got a big break in September when Hyde shifted gears and backed their cause. He was apparently moved by an emotional trip he made to Korea and two other Asian countries over the August recess. More importantly, Hyde was said to be angered by Koizumi’s decision on August 15—the date of Japan’s defeat in World War II—to visit the Yasukuni Shrine. More than 1,000 war criminals have their names inscribed in the shrine’s Book of Souls, including Hideki Tojo, the wartime prime minister who ordered the attack on Pearl Harbor and who was hanged in 1948. Koizumi’s visit provoked outrage across Asia and didn’t sit well with Hyde, the last remaining combat veteran of the Pacific campaign to sit in the House.

With Hyde on board, the source says, “We went from zero to 100 immediately.” Several members of the International Relations Committee did push to soften the resolution (removing, among other things, language that explicitly defined the treatment of comfort women as a “crime against humanity”). The advocates reluctantly accepted those changes, and on September 13, the Committee passed the resolution by unanimous consent.

Supporters believed the measure was now unstoppable. They expected it would soon be put on the “suspension calendar,” which would allow the resolution to pass the full House with a simple voice vote. The only obstacle to passage at that point was potential opposition from House Speaker Dennis Hastert—also of Illinois, and a former colleague of Michel’s—or House Majority Leader John Boehner, who controls the voting calendar.

On September 22, twenty-five congressional co-sponsors of the measure, including Mike Honda of California, the leading Japanese American in Congress, sent a letter to Hastert and Boehner asking them to bring the resolution to the floor before Congress adjourned for the November elections. But mysteriously, no word was heard from the G.O.P. leadership about when the resolution would be brought to a vote.

Exactly what happened next is not clear, but word on the Hill is that the Bush Administration, Michel, and other Japanese lobbyists went to work on Boehner—and on Hastert, who reportedly is hoping to be named ambassador to Japan after he retires and who made clear that he was unhappy with the resolution. By last Wednesday [September 27, 2006], Boehner’s office had made clear that the comfort women resolution would not be brought to a vote before the end of the week—a key deadline since Congress would be adjourning until after the midterm elections. (Michel declined to return calls, as did the offices of Congressmen Boehner and Hastert, both of whom may be preoccupied with other pressing matters at present.)

The measure could conceivably be revived during the upcoming lame-duck session, but for now it looks like Japan has again bought itself victory on the Hill. “The reality is that there is little we can do for the comfort women,” says Kotler. “They’ve lived with this hell for sixty years and most of them are going to find peace soon. The real importance of the bill is that it would serve as a precedent for going after the miscreants and perpetrators running today’s rape camps and help protect future generations of women from similar violence.”

This article was published by Harpers.org on Thursday, October 5, 2006, as part of Washington Babylon, a weblog focused on political corruption in Washington, D.C. Ken Silverstein is the Washington editor for Harper’s Magazine.

Alexis Dudden is associate professor of history at Connecticut College and author of Japan’s Colonization of Korea: Discourse and Power.

Posted at Japan Focus on October 21, 2006.