Engaging History and Peace in a Time of Conflict: A New Documentary on Japan’s Constitution

by Eriko ARITA

[Rarely does a documentary film, many months in production, appears

as timely as the nightly news when it’s released. But the premiere in Tokyo

on April 23 of “Japan’s Peace Constitution” (Japanese title: “Eiga

Nihon-koku Kempo”), directed by Japan Focus associate John Junkerman, comes

at a moment when tensions with China and Korea over Japan’s war past are at

their highest levels in decades. The film, produced by the Tokyo independent

production house Siglo, shows that the drive to revise the Japanese

Constitution cannot be divorced from an understanding of that history or

from the impact revision will have on Japan’s relations with its neighboring

countries.

In order to provide an international perspective on the constitution, the filmmakers traveled to eight countries, with interviews ranging from American historian John Dower on the making of the constitution to Syrian and Lebanese journalists on the dispatch of the Self Defense Force to Iraq. Chalmers Johnson provides a grounding in the “base world” American empire, and Korean historians Kang Man-Gil and Han Hong Koo appeal to Japan to fully acknowledge its past in order to embrace a future of constructive engagement with Asia. Japan Focus]

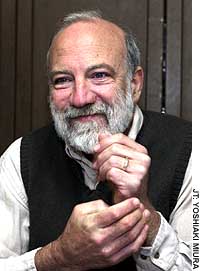

If Japan revises the Constitution’s war-renouncing Article 9 and officially designates its military as such, other parts of Asia will increase their arms buildups and war will become a possibility, according to American film director John Junkerman.

The Tokyo-based director, who recently completed the documentary “Japan’s Peace Constitution,” said in an interview that Article 9 has kept Japan from resorting to use of force and reassured other parts of Asia that the country does not pose an aggressive threat.

“But if Article 9 is revised and the Self-Defense Forces are called a military and given that right of being engaged in collective . . . defense, Japan’s neighbors are going to say ‘there is nothing anymore that constrains Japan, therefore we have to rebuild up our arms as well,’ ” Junkerman said.

On Tokyo’s disputes over South Korea-controlled islets known by Japan as Takeshima, and the Japan-controlled Senkaku islets, which are claimed by China and Taiwan, he said, “They could very easily escalate into increased tensions and to wars.”

Junkerman’s film tells how the constitutional revision is an international issue, not a domestic one, through views of 12 intellectuals from Japan and overseas, including China, South Korea and the U.S.

Chalmers Johnson, director of the Japan Policy Research Institute in San Diego, said that Japan had apologized for its aggression in East Asia by renouncing the use of force via Article 9.

“To formally renounce Article 9 is to renounce the apology,” he said in the film.

The film also shows testimony from South Korean women who were forced into sexual slavery for the Japanese Imperial Army, and their protest in front of the Japanese Embassy in Seoul, where they demanded that Tokyo apologize and stop its alleged militarization.

To discuss the Constitution, Junkerman noted it is indispensable to look at the history of Japan’s aggression in Asia. He said one of the reasons for making the film was to educate Japanese youth, who are less aware of what happened.

The film traces the process of establishing the Constitution from 1945 to 1947 through interviews with John Dower, an expert on Japan’s postwar history and a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and former University of Tokyo professor Rokuro Hidaka.

Although the Liberal Democratic Party claims the Constitution was drawn up by the U.S. and Japan should make its own, the experts argued that citizens’ groups and political parties debated the Constitution and the General Headquarters of the Allied Forces incorporated their proposals in its draft.

Junkerman said he learned of Japan’s war-renouncing Constitution when he visited the country in 1969. Amid the Vietnam War, the Constitution appeared to him as an enlightened document that shows how things ought to be in the future.

But amending the Constitution has been the topic of debate for decades, partly due to U.S. pressure for Japan to play a greater security role during the Cold War.

“I think the U.S is largely responsible for the pressure on Japan now to change the Constitution. So as a U.S. citizen, I see my responsibility to do what I can to counter that pressure from the United State,” he said.

Earlier this month, the LDP unveiled an outline of its planned amendment that proclaims the SDF a military tasked with defending Japan. Although the outline does not stipulate that Japan would exercise its right to collective defense, some LDP lawmakers proposed stipulating that right in laws to be enacted.

Junkerman worries over what he feels is the LDP’s desire to clear the way for the SDF to engage in offensive action without constraint, such as what he perceives the U.S. to be doing in Iraq. SDF troops are currently in Iraq on a humanitarian mission and are only allowed to use their weapons if fired on.

“It was a war that had no justification whatsoever. Iraq had not attacked the United States and certainly it had not attacked Japan,” said Junkerman, criticizing Japan’s support for the war and its perceived intent to join in such armed conflict.

LDP lawmakers claim Japan should have a military in name and make active efforts to help keep the peace in the international community. But Junkerman feels Japan can contribute to the world in a different way.

In a scene in his documentary, a shop owner in Syria says Japan suffered the most from wars and he imagines the Japanese don’t want to send the SDF overseas.

The image of Japan as a peaceful nation is common in the world, Junkerman claimed, adding Japan should take an aggressive role in seeking peaceful solutions to conflicts.

“This is the ironic thing — that there is no doubt that many Japanese feel a lack of pride about Japan’s role in the world. And the simple solution to that in many people’s minds is to have a strong military,” he said. “But . . . the Japanese people could have pride in their government as being a leader in the world in bringing about peaceful and constructive solutions to international problems.”

[The documentary premieres April 23 at Nakano Zero in Tokyo and May 28 at Chuo Kumin Hall in Osaka. DVD and video, and a companion book (all in Japanese) are available from Siglo (www.cine.co.jp. The English version of the film in in production; check the Siglo site for availability. For more information, call Siglo in Tokyo at (03) 5343-3101.]

Eriko Arita is a staff writer for The Japan Times.

This article appeared in The Japan Times on April 19, 2005. Posted at Japan Focus on April 19, 2005.