On May 7, 1952—in a twist of events that journalist Murray Schumach of the New York Times would later describe as “the strangest episode of the Korean War”—a group of Korean Communist prisoners of war “kidnapped” US camp commander Brigadier General Francis Dodd of the Koje-do POW camp. Located just off the southern coast of South Korea, the island contained the largest US-controlled camp during the Korean War.1

POW Joo Tek Woon, who was the spokesman elected by the members of Compound 76, had placed multiple, repeated requests to meet with Dodd, and that afternoon, Dodd finally agreed to meet with Joo. They met at the main gate of the compound, the barbed-wire fence between them. A small group of prisoners of war accompanied Joo, and one of them served as a translator. The list of topics to be discussed was lengthy, ranging from mundane complaints about camp logistics to the larger issue of POW repatriation, which was the last remaining subject of debate at the ceasefire negotiations taking place in the village of Panmunjom.

During this meeting, the gate opened to let a large truck carrying several tons’ worth of tents through. One of the POWs, Song Mo Jin, a large man of considerable strength, walked slowly through the gate, waited until Dodd put away the piece of wood he was whittling, stretched his arms as he pretended to yawn, and then grabbed Dodd. The POWs literally carried Dodd into the compound, closing the barbed-wire fence behind him. Soon, the POWs unfurled a large sign, approximately twenty-five feet long and three feet wide, over the main compound building. The following message in English had been painted on the banner: “We have captured Dodd. He will not be harmed if PW problems are resolved. If you shoot, his life will be in danger.”2

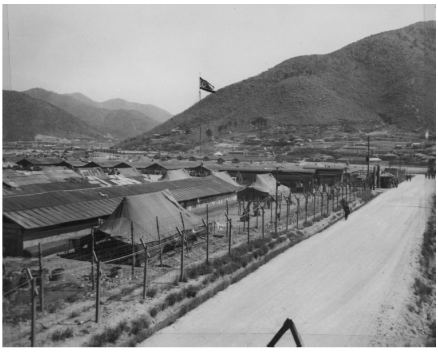

On Saturday morning, May 10, tanks began arriving to the island by ship. A heavy rain was pouring down, and at least twenty Patton and Sherman tanks filed down the muddy roads toward Compound 76. The US Army had explicitly forbidden the presence of any media on the island, but one journalist—Sanford L. Zalburg—had managed to get onto the island by the grace of a Korean fisherman and his twenty-foot boat, traveling four hours through the “rain-swept seas” from the town of Chinhae on the peninsula to the island of Koje. Approaching the island at two thirty in the morning on Saturday, he described the island:

From miles out you could see Koje’s prison camps. The island is large, but the prison camps are concentrated in one section.

We landed at a village. … A mile or so on either side of the village strings of lights blazed over the prison enclosures and the guards quarters and camp. Blue-gray colored light poured down into the enclosures from searchlights on the mountainside. …

Koje Island compounds are heavily barbed wired, with two high wire fences surrounding each plot. At night the lights blaze down. In the corners of the compounds are three story high guard houses where machine guns are mounted.3

Army jeeps manned by armed military personnel were patrolling the entire length of the coast surrounding the camp, and armed foot patrols could be seen also. To Zalburg’s eyes, Koje Island had become a military fortress, or in the words of Icle Davis of the 156th Military Police Detachment, Koje was an “Alcatraz” for the Korean War.4

Before being escorted off the island with a scolding by the US Army, Zalburg was able to talk with a few US infantry officers. One infantry officer who had been on duty at Compound 76 during Dodd’s captivity told Zalburg that “he could see Dodd plainly. The General’s clothes were freshly washed, he said. Dodd was about 100 yards away and surrounded by a great mass of Communists. None of the Reds laid a hand on Dodd.” The juxtaposition between the seeming order and calm within Compound 76 and the demonstration of sheer force by the over twenty armed US tanks moving steadily toward Compound 76 was the scene that greeted Zalburg on that Saturday morning.

Rumors of the POWs’ capture of Dodd and a brief press release by the US Army sent the US press into a frenzy. The front page of the Los Angeles Times on May 9, 1952, blared: 8TH ARMY ORDERED TO FREE GENERAL HELD BY RED POWS. By and large, the reaction was one of disbelief. “Sensational,” “bizarre,” “incredible,” and “fantastic”—a vocabulary of the unbelievable, the unfathomable, was mobilized by the editorial desks and the journalists who had the task of reporting the event to the American public.5 Each newspaper and each statement issued by the US Army echoed the similar sentiment—why had the POWs kidnapped the camp commander? Every newspaper stressed that the POWs had made a rather unusual request: “It was disclosed that the Communists had asked for 1,000 sheets of paper [presumably writing paper] and that this already had been sent to the island. … The purpose was not clear but the requisite order was issued by General Colson.”6 By the next day on May 10, the Atlanta Daily World was calling the kidnapping “a bizarre episode.”7

At the press conference General van Fleet held with the media, Lieutenant Colonel James McNamara, van Fleet’s public relations officer, described the situation as such: “The Communists are talking with General Dodd. Apparently they are trying to get as much as they can. General Dodd is apparently holding out and talking to them. It is a one-day Panmunjom.” 8 Even the US Army personnel on the island of Koje were not clear on what the demands of the POWs were. According to Zalburg, “one officer said that the Communists ‘keep making demands, sort of like at Panmunjom.’”9 The cluster of tents at the village of Panmunjom where the armistice negotiations were taking place had become a symbol of a certain type of negotiating. And indeed, the corollary between the activities within Compound 76 on Koje-do and the negotiations in the tents at Panmunjom signaled a set of stakes in the conflict that challenged the bounds of the imagination of the US mainstream press.

The term “prisoner of war,” in this historical moment, did not merely describe a category of wartime status. During the Korean War, the figure of the prisoner of war became central to explaining the meaning of the conflict itself, whether it be anti-imperial resistance, anti-Communist Cold War conflict, or a civil war. This story moves from the negotiating tents at Panmunjom to Compound 76 at United Nations Command Camp #1 on the island of Koje. A close reading and microhistorical study of the Panmunjom negotiations over POWs and the Dodd incident itself reveal that the conversation and conflict effectively revolved around the structural legacies of the 1945 division of Korea at the 38th parallel and the subsequent foreign occupations on the peninsula by the United States and the Soviet Union. The stakes were about the meanings of effective postcolonial liberation and sovereignty as the legitimacy of the 1948 elections held in the north and south respectively was forced onto the table of war by both the POWs at Koje and the negotiators at Panmunjom.

However, diplomats and policy makers fashioned the figure of the prisoner of war as central to the moral discourse underpinning the Cold War. On May 7, 1952, in the pressroom of the White House, perhaps no less than twelve hours after the kidnapping on Koje Island, President Harry Truman made a statement regarding the ongoing armistice talks in Korea. “There shall not be a forced repatriation of prisoners of war—as the Communists have insisted,” he announced. “To agree to forced repatriation would be unthinkable. It would be repugnant to the fundamental moral and humanitarian principles which underlie our action in Korea. … We will not buy an armistice by turning over human beings for slaughter or slavery.”10 The prisoner of war was, essentially, a propaganda item on the negotiating table inside the tents at the village of Panmunjom. But the controversy surrounding the voluntary repatriation issue signaled a more fundamental problem than a simple claim to morality in the post–World War II global order.

The cease-fire negotiations had begun on July 10, 1951, and by the end of the year all parties had agreed on the location of the cease-fire line near the 38th parallel. A single item of debate—Agenda Item 4, which concerned the matter of prisoners of war—was still on the table. However, on January 2, 1952, US delegates presented a new demand—voluntary repatriation. The Chinese and North Korean delegates pointed out that the 1949 Geneva Conventions on the Treatment of Prisoners of War required mandatory repatriation. The POWs at Koje Island were all too aware of this proposal. Starting in December 1951, the United States, eager to make preliminary estimates of how many POWs would choose not to repatriate, began sending interrogation teams to Koje Island to conduct “repatriation screening.” Certain POW compounds resisted the entrance of these military interrogation teams. By February 1952, the US sent a memo from Panmunjom pushing for the preliminary screening of all POWs.

On February 18, US and Republic of Korea Army (ROKA) military interrogation teams accompanied by 850 US troops from the Third Battalion of the 27th Infantry arrived at Compound 62 at 5:30 a.m. Compound 62—which housed Korean Communist civilian internees (CI), people who had been formerly classified as “prisoners of war” but whose status was changed to “civilian internee”—had been one of the compounds which had successfully barred the entrance of the interrogation teams in December 1951. The arrival of the troops at the compound before daybreak was part of the strategy to take the 5,600 civilian internees within the compound area by surprise. The received orders stated that the military personnel must take control of the compound, line up the civilian internees for breakfast, and conduct them to the latrines afterward. Then, according to the testimony of Lieutenant Colonel Norman Edwards, the orders explicitly instructed, “When breakfast is finished and everything is ready, conduct the polling team to each area and begin polling. … Keep the CI’s squatting or lying down.”11

However, the plan did not unfold as anticipated. By 9:00 a.m., one US Army enlisted man was killed, fifty-five civilian internees killed, four US Army enlisted men wounded, and 140 civilian internees wounded—of whom twenty-two later died of the inflicted wounds. Alerted to the presence of US military troops surrounding the compound, the internees met the troops with homemade cudgels, barbed-wire flails, and hundreds of stones. The majority of the internees died from wounds inflicted from concussion grenades. On May 7, 1952, at the barbed wire fence while conversing with Brigadier General Dodd, POW Joo Tek Woon was clear that he wanted to discuss the cessation of repatriation interrogation screening, given the deaths from February 1952 and the ongoing negotiations at Panmunjom. In his own May 7, 1952 statement on the Dodd kidnapping, President Truman announced, “The United Nations Command has observed the most extreme care in separating those prisoners who have said they could forcibly oppose return to Communist control,” revealing that he clearly understood how the kidnapping of Dodd was a possible threat to this characterization of US military control. It was absolutely necessary to maintain that the Korean Communist POWs responsible for kidnapping Dodd were fanatics.12

The story of the Dodd kidnapping was the invention of different strategies of war and diplomacy—but the site of invention was neither the battlefield nor the negotiating table with career diplomats and politicians. Instead, the questions of sovereignty, decolonization, and self-determination were played out in the POW camp on Koje Island and the tents at Panmunjom. The Dodd kidnapping revealed how the Korean War was a conflict that the 1949 Geneva Conventions had not anticipated. As the issue of POW repatriation became the focus of the Panmunjom negotiations, the 1949 Geneva Conventions became a central reference point. But it soon became clear that the prescriptions of the 1949 Geneva Conventions did not encompass the very real geopolitical shifts of the decolonizing world. The 1949 Geneva Conventions still essentially regarded warfare as a conflict occurring between two sovereign nation-states, and the Korean War would prove to be the first, direct challenge to its prescriptions formulated by the “international community.” With the future of the 38th parallel, the line of division proposed by the occupying US military forces upon Korea’s liberation from Japanese colonial rule, in question, the political issue of postcolonial sovereignty on the Korean peninsula was central to all of the conflicts playing out in the Korean War, whether it was a civil war, a Cold War “hot war,” or an anti-imperial revolution. As the United States and the United Nations sat down at Panmunjom with representatives from the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, the situation brought into stark relief that high-level negotiations were about to take place with an entity the United States and the United Nations did not recognize, calling into question the assumptions about the laws of war. The United Nations and the United States did not recognize the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) as a sovereign state, and the United Nations had entered the conflict as a belligerent. With the applicability of international laws of war called into question, the Korean prisoner of war represented the site on which resolution or conflict would proceed.13 The kidnapping of Dodd and the subsequent US military response was a moment when the POWs themselves, the US military, and the Panmunjom negotiators all attempted to claim the definition of the POW.

The Dodd Incident

Compound 76 in the Koje-do POW camp was located in the maximum-security area. On May 7, 1952, Brigadier General Dodd went to the compound to negotiate the entry of US interrogation teams to conduct preliminary repatriation screening. Holding a population of 6,418 prisoners of war, Compound 76 had already given a bit of grief to the administrative officials of the camp regarding voluntary repatriation screening, having persistently refused the entry of screening interrogation teams into the compound. Dodd was hoping to at least have the POWs agree to submit to fingerprint identification, since the POWs had made it a practice to give false names, swap ID numbers, and carry out multiple other acts to undermine US administrative oversight. 14

At 2:00 p.m. on May 7, Dodd was listening to the list of requests and complaints compiled by Joo Tek Woon through the barbed-wire fence. A group of approximately six prisoners of war had gathered for the meeting. Although Joo could communicate adequately in English, one of the other POWs from the compound was serving as the official translator. The topics of discussion ranged from arranging weekly compound spokesmen meetings to material requests such as socks, raincoats, and toothbrushes. According to the statement of General Raven, who had stood beside Dodd, prior to the kidnapping, Joo had repeatedly invited Dodd inside the compound: “Please come inside the compound where we can resolve all the problems at a desk,” and “please come inside and we will sit down and resolve our problems as gentlemen.” At around 3:00 p.m., a work detail passed through the gate, and the POWs seized Dodd and carried him into their compound. Kim Chang Mo, who was the compound monitor for Compound 76, instructed their chief compound clerk, O Seong Kwon, to paint a banner with the following English message: “We capture Dodd. We guarantee his safety if there is shooting, such a brutal action then his life is danger [sic].” The banner unfurled from the compound’s main building after Dodd disappeared inside the compound.

|

POW compounds involved in the Dodd kidnapping case (National Archives and Records Administration) |

Once inside the compound, Joo Tek Woon made an extraordinary gesture toward Dodd – an apology. In his interrogation transcript, Joo, the spokesman for Compound 76 who had ordered Dodd’s capture, recollected that after they had carried Dodd into the Compound, “I then … told the General … that we were sorry that we had captured him against his will, and that we would guarantee his safety and not harm him.” Without the barbed-wire fence between them, the terms and meanings of the roles of camp commander and prisoner of war could have been dramatically altered. With the camp commander behind the barbed-wire fence, Joo’s apology set a rather unexpected tone for Dodd’s duration in Compound 76. Joo’s statement, I suggest, revealed that it was crucial to establish that Dodd was still the camp commander, and the POWs were still prisoners of war.

What was at stake in this incident was the definition of the prisoner of war as a political subject. After Dodd’s capture, Joo immediately began negotiating with the authorities through the barbed-wire fence, stating that representatives from the other POW compounds must be brought to Compound 76 in order to have a meeting with Dodd. With over 170,000 prisoners of war housed in the camp on Koje Island, the US military and ROKA forces had created multiple compounds. In hopes of negotiating this point, the US Army brought the senior colonel of the DPRK Army, Lee Hak Ku, to the main gate. In the words of Colonel William H. Craig, Lee was “the most influential officer PW.” But on arrival at the compound, Lee simply stated: “it would be impossible to hold a meeting with a barbed wire fence separating us, therefore it would be necessary to enter the compound.”15

O Seong Kwon, the twenty-two-year-old POW clerk in Compound 76 who had also translated the words for the sign announcing Dodd’s capture, went with Captains Havilland and Carroll to each compound in the maximum-security section. He spoke with the spokesman and commander of each compound, telling them about the successful capture of Dodd, “and that a meeting would be held with the General in Compound #76, and that they should all come.” Kwon and the two US captains went to Compounds 96, 95, 607, 605, and then 66 and 62, bringing two representatives from each compound that held Communist POWs.16

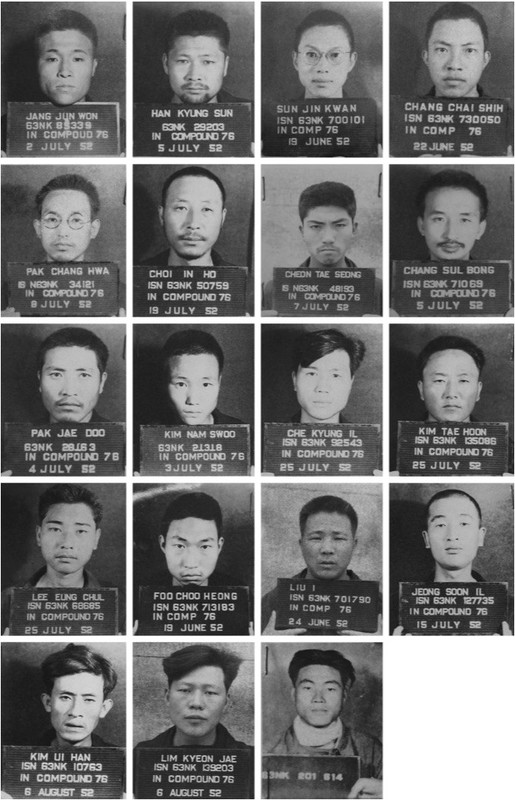

Eventually, all the representatives from other Communist compounds arrived at #76. After multiple meetings with Dodd within the main compound tent, they moved to the Civilian Information and Education (CIE) building—the largest structure the compound designed for teaching US democracy and English to POWs. Now, however, it had been transformed into the site for a POW organizational activity unanticipated by the US Army. According to Dodd: “We were up on the stage of the platform; I would say there were about a dozen persons on the stage, and down in the chairs facing the stage, down on the lower level, there were three or four rows of persons.” 17 The POWs collectively formed the “Korean Peoples Army and Chinese Volunteers Prisoners of War Representatives Association.” Sitting at a desk on the stage above the members, Dodd signed a note recognizing this representative organization of POWs. This act of writing by Dodd was central to the project of the POWs—and it was clear that in order for the POWs to claim a redefinition of the POW as a political subject that they would need to transform—but also still require—the authority of the camp commander.

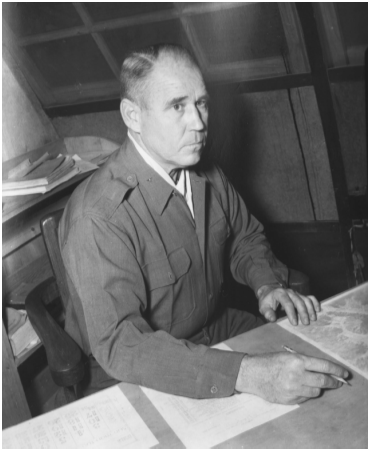

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Members of the Korean People’s Army and Chinese Volunteers Prisoners of War Representatives Association (National Archives and Records Administration) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Just as the space of the CIE building had been transformed into a diplomatic meeting hall, other spaces that Dodd occupied were similarly altered. After the meeting, the POWs escorted Dodd to a room that had been prepared for him: “rice mats on the floor and blankets on top of the rice mats, a wooden bunk, table, three chairs and rack on which to hang my clothes.” As Senior Colonel Lee Hak Ku remarked in his interrogation: there were always two guards outside of the room, but they were there to “maintain the prestige” of Dodd. His meals were prepared by the US military and delivered through the barbed-wire fence, the POWs noted in their interrogations—perhaps to help ease Dodd’s ulcerated stomach, they did not give him their POW rations. But also, perhaps eating the POW rations would have challenged Dodd’s hold onto his authority as camp commander. A performance of North Korean songs and plays had been planned that evening in the CIE building—and Brigadier General Dodd was a guest at this performance.18

The next morning, the POWs had arranged a certain morning routine—or ritual perhaps—for Brigadier General Dodd. In the five-hundred-page expanse of the investigation case file, there is one interrogation of a POW who was not directly involved with the kidnapping or the creation of the POW representative body—An Jong Un, a POW who served as the compound doctor. He gave the following testimony during his interrogation:

Q: What knowledge do you have concerning the seizure of General DODD?

A: An unidentified POW came to the dispensary and requested that I accompany him to a tent near the mess hall in 3rd Bn area to treat General Dodd. En route to the tent I met Lee Hak Eu and he asked what I was doing. When I explained that I was going to treat the General, LEE stated, that is fine, go ahead. Upon arrival at the tent, General DODD was taking a bath in a metal tub made from an oil drum. About three (3) PW monitors were washing the General’s body. … When the General had finished bathing I examined his finger and knees and observed they were healing. The Interpreter told me the General had a cough when he woke that morning, so I listened to his heart beat and examined his chest. He appeared to be in good condition. … In leaving, the General gave me a pack of cigarettes.19

The spectacle of Dodd being bathed by three POWs and then the careful medical attention Dodd received toed a line between the assertion of complete surveillance over his body and the provision of special services to an elite guest. Dodd was unmistakably a prisoner under the care of his captors, who were prisoners of war. Yet, there was no reversal of a binary hierarchy of power between a POW camp commander and the POW. The POWs did not replace Dodd in his position as camp commander. Instead, the POWs carefully marked Dodd’s body and the space of the compound itself to establish and assert Dodd’s authority—which they explicitly made contingent on their own authority as a collective of representatives for the POW camp.

On May 8, the POWs gave Dodd the most important document of the incident: a list of eleven functions and demands of the POW representative organization. Item 7 on the list was the most revealing: “In order to secure the business of this institute, we request four tents, ten desks, twenty chairs, one hundred K. T. paper and two hundred dozens of pencils, three hundred bottles of ink and two hundred stencil paper and one mimeograph.” The organization wanted to create their own archive, their own bureaucratic overseeing function, for the POWs. When we ponder the meaning of such a demand and look at the very first item on their list of organizational functions, we can see how this move toward establishing the means of an archive on the POW was also a move toward claiming a legitimate sovereignty: “1) We organize the representatives of PW’s association by total PWs of Korean Peoples Army and Chinese People’s Candidates that are confined in Koje Island.” In his interrogation, Joo stated that after Lee Hak Ku was elected president of the PW representative association, he effectively “became the commander of all PW Compounds in the UN POW Camp #1.”20

The bureaucracy they would create would approach the POW as the subject of a state, not simply a wartime category. The single, most important demand the POW organization made was the cessation of US military repatriation screening, claiming that the United States was forcing subjects of the DPRK to renounce the state’s sovereign claims over them. Using their position as prisoners of war, these representatives in turn forced the international community to ask what type of political collective body the DPRK was—and to argue that it was a legitimate state.

In an effort to lessen, or triage, the damage from the capture of Dodd, the US military sent in General Colson to become the camp commander of Koje. Colson’s duty was to announce to the POWs on his arrival that Dodd was no longer in command, and therefore all negotiations with him would be null and void. Colson delivered the following message via loudspeaker and writing to the members of Compound 76 at five minutes after midnight, the night of Dodd’s capture:

At about 1500 hours of 7 May certain PW of Compound 76, maliciously attacked Brigadier General Francis T. Dodd, then CG of this Camp and Lt Colonel W. R. Raven, CO of Enclosure Number 7. General Dodd against his violent opposition was forcibly carried into Compound 76 where he is now held a prisoner. Such an action is contrary to all the principles of the Geneva Convention. I am the new CG of this Camp and as such I am authorized by the rules of the Geneva Convention to order you to immediately release General Dodd and permit him to return safely. I do hereby order that you release him unharmed.21

Dodd was not released. Instead, altogether twelve messages were sent through the barbed-wire fence to the new camp command. A message sent to the US command on May 10, signed by Lee Hak Ku on behalf of the POW representative organization, provides a crucial frame through which to understand the functions of the organization they had created. “This Representative Group announce once again that the unwilling detention of Brig. Gen. Dodd, US Army, your predecessor by this Representative Group is the legal leading measure for the protection of lives and personal rights of our POWs who have been intimidated by unjust management handled by your authorities having decreased the authority of Geneva Convention and nullified the said Convention by the illegal management of POWs and the violence against the POWs.” 22 The invocation of the Geneva Convention in this exchange message makes a very crucial discursive move: it unhinges the authority of the United States from the moral authority of international humanitarian law by stating that the United States was not synonymous with the international order.

Lee ended the message by writing, “I announce that American Brigadier General Dodd is, as he has reported, in utterly safe condition, being protected from all danger and there is not even the smallest change in his sanitary or mental condition could be seen. He is discussing with us in most usual condition. Your health and new result of practicing Geneva Convention is hoped for. Representing the representatives group of KPA and Chinese volunteer Troop PW by the approval of the then CG of PW Camp. Signed Lee, Hak Koo.”23 The POWs were not necessarily either surprised or perturbed by the change in command. They shifted bureaucratic strategies in their negotiations—all statements regarding past events of violence, and such, that had occurred under Dodd’s command would be verified by Dodd’s signature, and those statements regarding the future entitlements and functions of the POW representative organization would be signed by Colson.

On May 10, 1952, both Dodd and Colson had marked their signatures on the corresponding statements. On Dodd’s release, the US military, in turn, immediately demoted both of them. It was the fact that they had signed their signatures on documents written up by POWs attesting to violence in the camps among multiple other items that led to the quick demise of both of these men’s military careers. Their signatures were deemed acts of transgression.

|

|

This edited excerpt comes from Chapter Four, “Koje Island: Mutiny, or Revolution,” of The Interrogation Rooms of the Korean War: The Untold History (Princeton University Press: 2019). In this book, I tell the story of the Korean War through the wartime creation of, and intimate encounters in, four different military interrogation rooms: the US military, South Korean paramilitary youth groups, the North Korean and Chinese militaries, and the Indian Custodian Force. Traditional military histories of the Korean War have often focused on the 38th parallel as the pivot to a story that has largely remained on the battlefield and in political backrooms, where the stakes have been either the US-Soviet Cold War or the North-South civil war on the Korean peninsula. The Interrogation Rooms of the Korean War reframes the Korean War as a global story of the making of liberal warfare in the mid-twentieth century, as the interrogation room entered the international spotlight when the war shifted from being waged over the violation of a border (the 38th parallel) to being waged over the violation of a human subject (the prisoner of war). Human interiority became the realm of warfare as the Korean War explicitly became a conflict where formal decolonization thrust international laws of war and the nation-state system into simultaneous crisis.

Drawing on newly declassified U.S. military intelligence files from the Korean War, oral history interviews with both former prisoners of war and interrogators, and bringing together multi-lingual and multi-national archival research on the POW issue, I uncover a trans-Pacific human drama of wartime survival and violence that spans three continents, multiple wars, and twentieth-century anti-colonial revolutions. Opening with Japanese American internment and the U.S. occupation of Korea, the book tracks two generations of individuals creating and moving in landscapes of interrogation in the United States and Asia from 1940 through the 1960s. The story follows a thousand Japanese Americans to Korea where they served as interrogators during the Korean War, traces the post-war journeys of Korean prisoners of war shipped by the United Nations and Indian military to India, Brazil, and Argentina, and finally maps out the movements of American POWs through the interrogation networks within Chinese and North Korean POW camps. The Korean War was a moment where both Asians and Americans became central to the story of the making of warfare in an era marked by World War II internment, US ambitions in East Asia, and the growing non-alignment movement.

The Korean War presents a three-fold puzzle for the scholar today: it was not officially a war but a “police action”; it is the only “hot war” of the Cold War that has still not come to an official end; and it is also the “forgotten war” within US mainstream historical consciousness. Yet it remains among the most consequential of US wars of the post-1945 era, its importance underlined by the inability to reach closure. The book argues that the Korean War was a foundational moment within a much longer and broader struggle over claims to political recognition and legitimate governance. In essence, the military interrogation room became an important battleground for demonstrating what kinds of governance would determine the contours of the international order. The Interrogation Rooms of the Korean War argues that the liberal project of regulating, not eliminating, warfare on the decolonizing globe was, in fact, a fundamental battle over defining sovereignty in the post-1945 era. Sovereignty in the age of Cold War decolonization was not simply about geopolitical territory, but also fundamentally about subject-making as the terrain for reconfiguring power and legitimacy, a historical legacy that continues to impact the wars of intervention today. The Korean War’s awkward, puzzling character is not the contradiction, but rather exactly the point.

Notes

Murray Schumach, “Gen. Dodd Is Freed by Koje Captives Unhurt and Happy,” New York Times, May 11, 1952.

Details from Case File #33; Box 8; Post Capture Summaries; Historical Reports of the War Crimes Division, 1952–54, War Crimes Division, Records of the Office of the Judge Advocate General; Record Group 153; NARA, College Park, Maryland (hereafter “Case File #33”).

Alexander Liosnoff Collection, Box 1, Folder: Korean War Press Releases and Wire Service Teletypes (Brigadier General Francis T. Dodd), Hoover Institution Archives. (A version of Zalburg’s narrative appears in the Chicago Daily Tribune on May 12, 1952, in “20 Tanks Scare Reds into Freeing Dodd: Army Rushes Force to POW Island by Ships.” At that time, Zalburg was working as an International News Service correspondent.)

“Use Force to Release Hostage if Necessary, Gen. Ridgway Rules,” Los Angeles Times, May 9, 1952; “UN Rejects Red Terms to Free General,” Atlanta Daily World, May 10, 1952; “Koje Fantastic,” New York Times, May 11, 1952.

Lindesay Parrott, “U.S. General Seized by Red Prisoners at Koje as Hostage,” New York Times, May 9, 1952.

Alexander Liosnoff Collection, Box 1, Folder: Korean War Press Releases and Wire Service Teletypes (Brigadier General Francis T. Dodd), Hoover Institution Archives.

Special to the New York Times, “truman endorses u.n. truce stand rejected by reds; He Denounces as ‘Repugnant’ to World Foe’s Insistence on Repatriation of Captives backs ridgway ‘package’ Acheson and Foster Also See Allies Offering Fair Terms for Cease-Fire Accord truman endorses korea truce stand,” New York Times, May 8, 1952.

Case file #87, Box 5, POW Incident Investigation Case Files, 1950-1953; Office of the Provost Marshall; Office of the Assistant Chief of Staff, G-1; Headquarter, US Army Forces, Far East, 1952-1957; Record Group 554; NARA, College Park, Maryland.

There is a great deal of scholarship examining and analyzing the development of international humanitarian law especially after 1945. For a general overview, see Geoffrey Best, War and Law since 1945 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1997) and his other monograph, Humanity in Warfare (New York: Columbia University Press, 1980). A significant book on Panmunjom is Hakjae Kim, P’anmunjŏm ch’eje ŭi kiwŏn: Han’guk Chŏnjaeng kwa chayujuŭi p’yŏnghwa kihoek [The Origins of the Panmunjom Regime], (Seoul: Humanitas, 2015).

Box 7; Post Capture Summaries; Historical Reports of the War Crimes Division, 1952–54, War Crimes Division, Records of the Office of the Judge Advocate General; Record Group 153; NARA, College Park, Maryland.