On July 8 1969, 19-year old US soldier Daniel Plemons was working at Chibana Ammunition Depot, Okinawa, in one of the most dangerous – and secretive – jobs in the US military: the maintenance of chemical weapons.

“There were 500-pound (227 kg) bombs filled with nerve agent and we were sandblasting the old paint off them before repainting and stenciling their markings. Our team had finished around 25 – then I started having trouble breathing and my vision became strange. Thinking it was just the dust, I stepped outside for a moment but when I went back inside, everybody was gone. I found them out the back of the building and they yelled at me to inject myself with my automatic spring-loaded antidote. I injected it into my upper thigh. It hurt – but that’s what saved my life.”

|

267th Chemical Company soldier, Daniel Plemons, stands in front of a military medical van in the US in 1969. Courtesy of Daniel Plemons. |

|

267th Chemical Company soldier, Daniel Plemons (Right) stands on a military base on Okinawa with a fellow soldier in 1969; he wonders whether his colleagues are sick, too. Courtesy of Daniel Plemons. |

For a week after his exposure to nerve agent, military doctors checked the blood of Plemons and the other 22 soldiers who had been working alongside him.1 But Plemons has never seen the results of his blood checks and he says they have been classified as “Secret.” Now he worries his exposure has affected not only his long-term health but also the health of his children. Since the incident, he has experienced problems breathing and, one year after the leak, he developed pneumonia which hospitalized him for two weeks. Today he suffers from neuropathy which prevents him from sleeping, standing or walking for long periods; his daughters have also developed serious health issues, including problems with the liver and gallbladder, which he wonders may be connected to his own exposure.

Clemons has visited VA clinics but the doctors have been unable to help, telling him there have been no scientific studies into the long-term health effects of nerve agent exposure. According to the VA’s official website, too, research into such long-term impact is “inconclusive.” Plemons has not been able to track down any of his colleagues and he wonders whether they are also sick – or even still alive.

Shortly after the leak, Plemons took part in a dump of concrete-encased barrels at sea roughly an hour’s sailing from Okinawa. Although not certain what the barrels contained, he suspects they were packed with the gear used to decontaminate the Chibana leak site.2

During his service at Chibana, Plemons often handled the rabbits, which provided an early-warning system for leaks of nerve agent. “When we inspected the storage igloos, we placed the rabbits in cages near the doorways to check for leaks. They die more quickly than humans when exposed.” At the time of the July 8 incident, Plemons heard from his colleagues that the rabbits in the vicinity had died – although he did not see them firsthand.3

Plemons does not recall any other incidents involving nerve agent, however, he says decades-old mustard agent munitions were also stored at Chibana. Liquid frequently bubbled from the shells and he and his colleagues had to clean them.

The 1969 accident at Chibana occurred at a pivotal moment in US-Japan relations during negotiations for the reversion of Okinawa. For the first time, the leak revealed the United States was storing chemical weapons overseas, forcing President Richard Nixon to announce on November 15, 1969 in a speech at Fort Detrick that the nation would not make first-use of chemical weapons.4 The leak also sparked mass demonstrations on Okinawa, compelling the United States to relocate the weapons including nerve and blister agents from Okinawa to Johnston Atoll in a mission called Operation Red Hat, which was completed in August 1971.5

Plemons departed Okinawa prior to the start of that operation but before he left the island he was ordered to carry out one final duty which still haunts him today: the destruction of some of the rabbits which had once been used to monitor for leaks. “There were hundreds of them and they ordered us to kill them. I don’t know why – they ought to have sold them off to kids. I’m not proud of the fact but I had to follow orders.”

|

This year, Daniel Plemons sits at his home in Missouri. Courtesy of Daniel Plemons. |

Today, Plemons says he is strongly-opposed to chemical weapons and war in general. He says he is happy no Okinawans were injured by such weapons on their island; also, he is happy Okinawa is no longer under US control and residents can enjoy more independence than they used to.

FOIA-released documents detail chemical weapon stockpile, defects

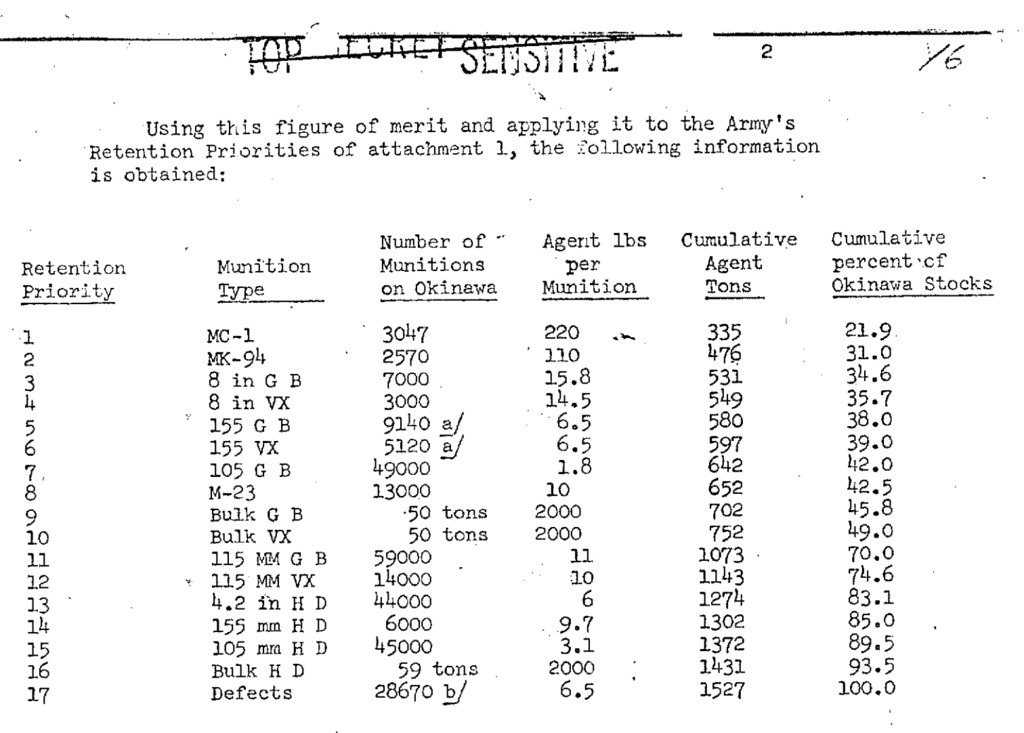

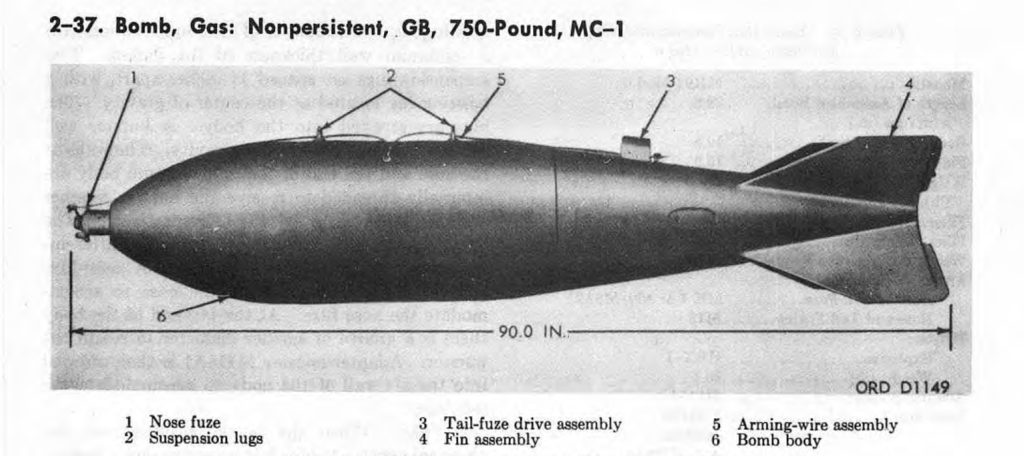

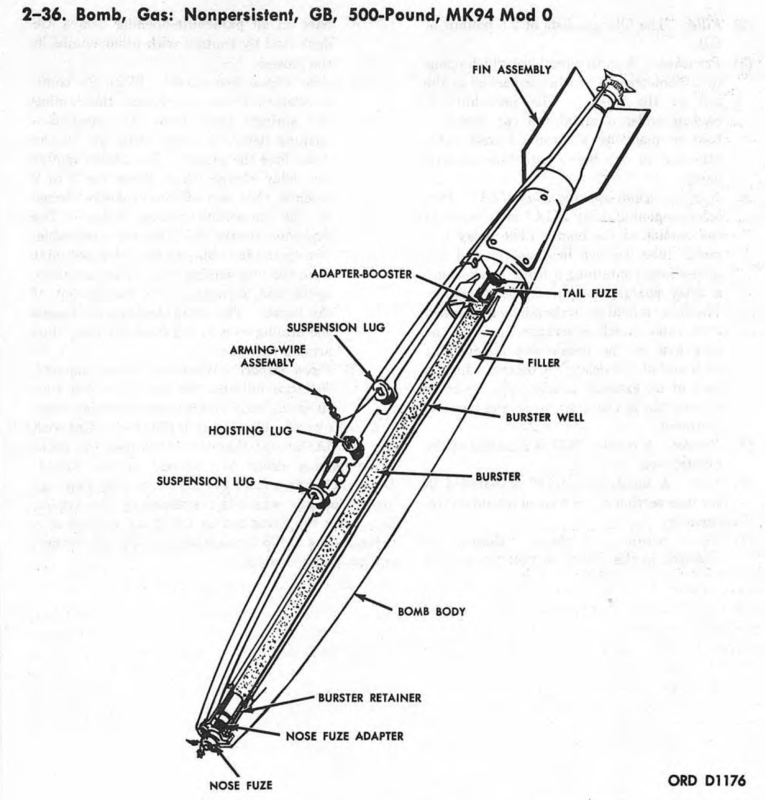

Formerly Top Secret documents released under the US Freedom of Information Act reveal the exact composition of Chibana Ammunition Depot’s stockpile of chemical weapons – and their dangers.6 The report from 1970 shows there were 13 different types of nerve and mustard agent munitions totaling almost 290,000 individual weapons; in addition, there were bulk containers of sarin, VX and mustard agent. The weapons included 3000+ MC-1 bombs each containing 100 kilograms of sarin and 13,000 landmines designed to spray 4.5 kilograms of VX agent when activated. The weapons belonged to all services of the US military.

|

Excerpt from a formerly Top Secret report lists the stockpile of chemical weapons at Chibana Ammunition Depot in 1970 |

|

The Chibana stockpile included more than 3000 MC-1 bombs packed with 100 kilograms of sarin; this photograph is from a Department of Army, Navy and Air Force manual dated April 1966 |

|

Diagram from an April 1966 Department of Army, Navy and Air Force manual depicts a MK94 bomb containing 50 kilograms of sarin nerve agent; in 1970 the Chibana depot held 2570 such munitions |

According to the report, almost 29,000 of the rockets at Chibana were categorized as “defects”; they contained a combined total of approximately 85,000 kilograms of sarin and VX nerve agent.

Exposure to even tiny amounts of nerve agent can cause symptoms such as breathing problems, convulsions and death. A small leak on July 8, 1969, exposed 23 soldiers and one US civilian at the depot [see accompanying article].

Japanese versions of these articles appeared in Okinawa Times on October 7, 2019

Notes

A brief summary of the incident was first reported ten days later by Wall Street Journal. “Nerve gas accident – Okinawa mishap bares overseas deployment of chemical weapons,” Wall Street Journal, July 18, 1969.

Until 1970, it was standard operating procedure for the US military – and other countries’ militaries – to dump chemical weapons at sea; often no records of such dumps were kept. For example, see: Ian Wilkinson, “Chemical Weapon Munitions Dumped at Sea: An Interactive Map,” James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey, August 1, 2017.

For an official account of what happened that day at Chibana, see Richard A. Hunt, Melvin Laird and the Foundation of the Post-Vietnam Military 1969–1973, Historical Office, Office of the Secretary of Defense, Washington DC, 2015, p. 337.

For a wider discussion of Operation Red Hat, see Jon Mitchell, “Operation Red Hat: Chemical weapons and the Pentagon smokescreen on Okinawa,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 11, Issue 30, No. 1. August 5, 2013.

Joint Chiefs of Staff, “Relocation of Chemical Munitions from Okinawa (Operation ‘RED HAT’)”, JCS Official Record, January 15, 1970.