Chiu Chin-po, or Chō Chin-bo (周金波) as he was known in Japan, was born in Keelung, Taiwan, in January 1920—twenty-five years after Japan acquired the island as a result of the Sino-Japanese War, 1894-1895. His mother took him to Tokyo when he was three, in 1923, to join her husband who was studying dentistry at Nihon University. In September that year, Tokyo was hit by the Great Kanto Earthquake that killed 100,000 people. The Chiu family was among those affected, and returned to Taiwan. Chiu attended “public school,” the elementary school for Taiwanese children, in Keelung and a few other cities. He recalled being bullied because he did not understand Taiwanese.

In 1934 he returned to Tokyo and attended schools affiliated with Nihon University where he went on to study dentistry as his father had. With ample money from his father, he associated with people in the arts, joining the Bungaku-za, the theater troupe that Kishida Kunio founded in 1937, as one of the first students. At Nihon University he and other students revived a literary magazine. There he published stories like I Am Not a Cat—a parody of Natsume Sōseki’s famous novella, I Am a Cat.

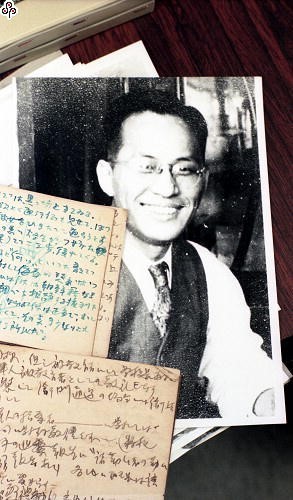

|

Chō Chin-bo |

In 1940, Chiu received a sumptuous magazine called Literary Arts: Taiwan (Bungei Taiwan) and, impressed by the many Taiwanese writers featured there, he was stirred to write. One of the founders of the magazine was the novelist and poet Nishikawa Mitsuru whose life was the reverse of Chiu’s: born in 1908, he lived in Taiwan since he was three and until he attended Waseda University. He was forced to leave Taiwan after Japan’s defeat in 1945.

After graduating from Nihon University in the spring of 1941, Chiu returned to Keelung to join his father’s dental clinic and became a member of Literary Arts: Taiwan. He wrote the story translated here, The Volunteer (Shiganhei), when the Governor-General, Admiral Hasegawa Kiyoshi, announced a plan for military volunteerism in June 1941. The story won the magazine’s first prize. (The idea of military volunteerism, shigansei, was promoted in Taiwan after Japan expanded its war in China in 1937. In April 1942, the first year that the program was implemented, 1,000 volunteers were accepted out of more than 400,000 applicants. In September 1944, conscription began.)

|

Chō Chin-bo Selected Works |

Following Japan’s defeat, Taiwan reverted to China, and General Chiang Kai-shek’s Kuomintang took over, bringing his army and people from China with him. Initially the Taiwanese welcomed them, but soon appalled by Chiang and his men’s abuse and corruption, they developed strong anti-China sentiments. On February 28, 1947, a riot erupted, and in the ensuing weeks between 18,000 and 28,000 people were killed. Chiu was arrested and tortured by Chiang’s police and military police. Subsequently, Chiu largely stopped his literary activities and his reputation as a writer in Japanese seriously suffered. He died in Keelung, in 1996. In the 1990s, a series of books was published reassessing his Japanese writings.

—Hiroaki Sato

Most of the information here on Chiu comes from Asahi Keiko’s entry on him in the online dictionary of modern Chinese writers.

The Volunteer

The Takasago-maru was gradually turning its hull. Loaded with tons of gifts for those waiting to welcome it, it moved ponderously. Carrying youth about to have reunions with their hometown or expecting their parents’ abundant favor, or those full of fantasies about the romance of the South, the ship was now about to deliver them to the bosom of their hometown. Entranced by the stylish make of the Takasago-maru, I indulged in my own thoughts for a while.

|

The Takasago-maru |

The ship that had carried me like this until eight years ago was one of the Yoshino-maru class, but I remember how it had nurtured the sweet, ample dreams of my student days. The last one that had brought me home—triumphant now that I was a college graduate—was the Asahi-maru, I recall, but, I don’t know why, I regarded the welcomers’ enthusiasm as if it were all someone else’s business and disembarked, feeling dark, depressed. Maybe that was because a whiff of sadness was lurking in me over the fact that I’d parted with the Tokyo life I’d lived for years, all alone, free. Solitude may make you feel lonesome, and freedom perilous, but I had felt a meaning in that life. Now I forgot even thinking of such a life. You’ve come home triumphant—the moment I was told that, I’d begun to take root in the red-brick floor of my house. That is, the complications of my profession and my family life had in no time sealed me in.

If today I hadn’t had this errand of welcoming my younger brother-in-law Meiki on the pier like this, I wouldn’t have been blessed with these pleasant reflections. Meiki came back by the same shipping route as mine.

As I was remembering this and that, I was tempted to take off my jacket and hang it from my shoulder. It was then that a man came out through the crowd, took off his Defense Organization hat and politely asked, “Haven’t you come here to welcome Chō Meiki-kun?”

“So, you knew. I remember you as Taka-san.”

“Yes, I’m Taka Shinroku. How do you do. I’ve come here, too, to welcome Chō-kun back.”

At first I was puzzled. I’d thought I was the only one who knew Meiki was coming home. I don’t like fussy welcomes, please don’t tell my family about this, Meiki had told me. But Taka Shinroku laughed, saying, I also received a letter like that.

“——So you are from Meiki’s school. I had no idea. I’m also a graduate of T junior high school,2 so we are a senior and a junior, aren’t we?” Feeling oddly friendly toward him, I invited him to sit next to me. He was a pleasant young man.

Yet he looked embarrassed at this and said firmly, “No, I may be from the same school, but that was when it was a public school.3 I didn’t go any further than higher elementary school.4”

“I see. Your National Language5 is so good, until just now I thought for sure you’d graduated from junior high.6”

That was not flattery. Oops, wasn’t what I thought. I had come to recognize him because I was sort of enchanted by his masterful use of the National Language. He also had a reputation for filial piety. Anyone exposed to his proper etiquette would have assumed that he’d gone beyond junior high.

While we were talking, the Takasago-maru had come so close to the pier it almost touched it. The welcoming throngs surged like an avalanche and surrounded the upper end of the gangplank.

“Shall we go?”

Even while talking to me, Taka Shinroku appeared constantly distracted by the ship. But I couldn’t stand the humid heat and the oppressive air created by the crowd.

“He’ll come up toward the end anyway, so we better wait here. It’ll be less crowded.”

“I’d like to see him sooner to see how he’s changed.”

He mumbled to himself as if resigned, but various emotions appeared to come and go in his face. Is he missing his friend or is he envious of him? I looked at his neck awhile as he hung his head. He had left his hair long but it didn’t have any unclean sense at all. It was a sturdy neck. His shoulders were tough, wide.

“Does he write you from time to time?”

“A letter a month on the average, but he doesn’t write so often as he does to you. Meiki seldom writes home, so they asked me to tell him to write, so I did, and he said there’s no one who would read his letters for them. That’s why he mainly writes you, his older brother-in-law, he wrote in his reply.”

“So that was his excuse. He writes me often enough, I must say. Some months he doesn’t write at all, but sometimes he writes three or four letters a month, one after another. At times I have to serve as a spokesman, even have to negotiate about money for him. Worse, they scold me because of Meiki.”

We laughed. The ship passengers had come up. A human fence formed before where we sat. Finally, we rose to our feet and looked for Meiki over people’s shoulders here and there, but we couldn’t find him.

“He isn’t here. He must be behind the last people.” Taka Shinroku, who was taller, said he couldn’t see him.

“He’s born to take it easy. He doesn’t do things like going ahead of others, I guess.”

“Still, coming up at the rear is a shame for a Keelung-ite.”

I get hot easily, and my shirt was already wet with sweat and clinging to my body. I’m a Keelung-ite after all. I’m unlikely to make a mistake at the pier I’m used to, I thought, and I made bold and sat back down on the bench, urging Taka Shinroku to do the same.

Someone like Meiki can’t possibly race to be first—so I was convinced for a reason. In his recent letters he had a number of words criticizing the crowdedness of vehicles in the Imperial Capital.7 Why do they compete to be the first? These are really despicable people, he wrote me, finding me, as he always does, to be the outlet for his complaints and grumbling. How will he, who has called people despicable, look today, I wondered playfully, but, in truth, I was too hot to really think about such things. In what way has he changed? Like Taka Shinroku, I wanted to see him as soon as possible. Since he entered professional school,8 he hadn’t returned during either of the two summer breaks. To know how he had changed, there was nothing other than his monthly letters. But he must surely have changed. The complaints and grumblings he lined up weren’t his usual moaning. In every letter he hadn’t slackened his persistent pursuit. I thought such growth rather admirable. No matter how favorably you look at it, among the students from this island studying in Tokyo, so many mediocre sons and daughters stand out. Their years in Tokyo up, each raised a shingle in their hometowns triumphantly, calling themselves part of the intelligentsia, flaunting the degree of bachelor of arts,9 but in reality none of them has any substance. I am no exception, but because I had directly experienced this, I couldn’t stand the thought that these people would be dismissive of Taiwanese culture.

As a consequence, in Meiki’s case, however dangerous a trick he might be performing, I wanted to bless him just for the fact that he could pull it off.

“He’s going to graduate next spring. Then why has he decided to come back this summer? A strange man.”

“He wrote in his letters he wanted to come back because Taiwan seems to have changed a lot.”

“If you are away for as long as three years, you imagine things like that, I gather. We’re eager to see him and he’s eager to see us, too.” When I said this, someone gently put his hand on my shoulder, so I turned to look.

As expected, it was Meiki. He was carrying a Boston bag and a basket of peaches he must have bought in Moji.

“Thanks for coming,” he said and shook my hand. His palm was large. His bones were hard. Under a tuft of hair carelessly covering his forehead, I didn’t overlook his friendly eyes brimming with tears.

“I haven’t seen you for three years.”

That was all. The three of us started walking in silence. There was only a smattering of people on the long overpass.

“How was the ship?” I found it somewhat odd to keep silent as if we were deeply moved. I wanted to find some way of starting a conversation.

“It didn’t roll at all. There were so many students I wasn’t bored, either.”

“That’s good. Being a student like that is something I never understood,” said Taka Shinroku enviously.

“Not that good. They may have been welcomed in the past, but they’re treated as some kind of burden these days,” Meiki said as if dismissing the notion. Perhaps tired out by the ship, his cheeks were sunken. Our conversation became intermittent as if we hadn’t said enough but at the same time as if we had said everything. Still, Meiki wasn’t able to remain unconcerned about what was going on in his family.

“Still seem to be worried about a bride for me, my folks I mean. It’s all so foolish. Remember I’m still a young man who’s just added one year to twenty? I don’t want to hurry.”

“You’ve gone completely in-land style,10” I said, and Meiki responded with a grin.

“That’s why I didn’t return last year and the year before. They pestered me so much about it in their letters I got scared to come home. I couldn’t even send my photos casually.”

“You mean you came back this time determined.” I teased him and he showed an exaggerated surprise.

“No laughing matter. I’ve come back feeling far more serious. Because I’ve gotten the feeling from your letters and the newspapers that Taiwan has changed a great deal. Once a week I went to the library to look at Taiwanese newspapers. They all talked about things like ‘training to become Imperial citizens’11 and ‘daily-life reform.’ In particular, the recent announcements of ‘name reform’12 and the ‘volunteer system’ have made me constantly anxious that I’m going to be left behind in everything. How Taiwan has changed under these current movements I desperately wanted to find out with my own eyes,” Meiki said, as if he meant to line up each of the words.

“Well then, how did you feel? They say that a traveler’s impressions often hit the bull’s-eye, don’t they? How about yours?” I was curious and asked.

“I was somewhat disappointed. My expectations may have been too great,” he said, and started clattering down the stairs, then stopped after a couple of steps. Upon hearing that, Taka Shinroku, who was a couple of steps further down suddenly turned around and said, “That isn’t so. Taiwan has been changing. It has been making big progress. Chō-kun still hasn’t seen what’s inside.”

“I wonder about that. To my eyes it’s as old-fashioned as it was. When I look around like this, there doesn’t seem to be much progress. Leave Tokyo for a month and you’ll see at least the position of a garbage box has changed.”

“Well, this may not be Tokyo. This is the countryside. Buildings and plazas don’t increase in just three years, do they?” Taka even flushed as he walked closer.

“No, I’m not talking about buildings or plazas. For example, even coolies and ginas13 haven’t changed much, don’t you think? Some minutes ago we saw some warriors in white robes,14 didn’t we? There were coolies and ginas who walked past in front of them unconcerned, weren’t there? I am talking about such specific things.” He appeared ready to become argumentative.

“Yes, Taiwan has certainly made progress,” I said. “It’s also certain that Meiki’s expectations were too great.”

The station was crowded with ship passengers waiting for the train into town. Out of the station, our eyes, directly hit by the sunshine, were lost in the white plaza.

“It’s hot after all, isn’t it?” Meiki cried and raised the basket of peaches above his head. Saying, “Excuse me for a moment!” Taka Shinroku left us and came back pushing a bicycle he had left with some caretaker.

“Just like a flag march!” Meiki marveled, staring at a woman in a long dress15 as she crossed before our eyes. With the lower hem of her dress fluttering in the wind, she, long-legged, seemed to make a swishy sound. So he feels nostalgic about such a thing, I thought enviously.

“The year I went to Tokyo, there was what was called a reform dress of Japanese-Chinese combination. Is it all right to wear long dresses these days?”

“Right, there was. But it died out in a wishy-washy way.”

“Long dresses are good, aren’t they?”

“In those days you’d agreed with the reform dress, hadn’t you?” Taka Shinroku riposted without losing a beat.

“At the time I was advocating an ‘environment theory.’ I thought that ‘training to become Imperial citizens’ could be created outside the environment.”

In that moment an omnibus turned a corner right near us. Comically panicked, Meiki jumped away. Taka Shinroku and I backed off a bit.

“Terrifying. The automobiles here,” Meiki said, laughing it off. As if to make a joke of it, the noon siren resounded.

“I’ll come tonight to see you,” Taka Shinroku raised his hand at us from his bicycle and rode away.

“Make sure of that. I’ll be waiting for you.”

“A nice guy, isn’t he?”

“We seldom have a man like that these days. Much more reliable than I am.”

“I heard he went to school with you.”

“It was a public school, and we’ve been good friends ever since. Above all, he is trustworthy. Yes, I should say he’s my only friend.”

“He speaks the National Language very well. I mistook him to be an in-land fellow. Is his parents’ a marriage between an in-lander and a Taiwanese?”

“No, it’s not a marriage between an in-lander and a Taiwanese. He went to work for an in-lander’s store as soon as he left school. It’s a big food store employing thirty clerks, I hear, and it has all of them live together in a single room without any discrimination between in-land and Taiwanese people. He appears to have learned the National Language while there. The way he wears a hakama, he does it far more perfectly than I can.”

I could only marvel, just listening to him.

“My ‘environment theory,’ to tell you the truth, became possible because there was the living experimental basis called Takamine Shinroku.”

“Takamine Shinroku”? I asked.

“Shinroku calls himself that using the surname Takamine among us.” With that, he burst into loud laughter. I didn’t understand why he did that.

“I see, he’s reformed his name.”

“No, he did that before the name-reform permission. The store had a manager called Takamine-san and he took good care of him, so Shinroku ended up calling him his older brother-in-law, I gather.”

“That’s admirable.” When I said this, Meiki seemed to say something like “Hmm.” Suddenly, he turned to me. “You’re my older brother-in-law, have you reformed your name?”

“No, while older folks are around, it’s hard to persuade them.” Troubled, I was evasive. To this Meiki said, more casually than might have been expected, “I guess that’s the way it is. I guess it won’t go that simply.”

He appeared to understand the matter perfectly. I’d expected him to direct a much colder criticism toward me. He had considerable concern about name reform, he had indicated in his letters. Or, was that concern of his as temporary as his environment theory? Now talking to him directly like this, it became less clear. How he had changed was far, far more unfathomable than what I had learned about Taka Shinroku’s life for the first time that day. The manner of change I could definitely discern was that he was no longer utterly nonchalant; he was now so acutely sensitive as to feel danger at even an omnibus making a turn. But to me that was in a realm I was no longer able to understand perfectly.

As I looked up at his broad forehead over which a tuft of hair fell, I felt a deep, incomprehensible loneliness.

Suddenly coming home and surprising my family, how will I excuse myself?—Imagining Meiki wondering so, I promised that night to meet him again and walked home.

That night, I selected three of the monthly magazines published in Taipei and visited Meiki at his home. It was just about ten o’clock and he was writing a letter to his friend in Tokyo. I invited him out for a walk to chat but he insisted on waiting for Taka Shinroku.

“Come to think of it, I haven’t given you a gift yet, have I?” He rummaged in his Boston bag and took out a small box.

“It took me three days to make up my mind on a gift. I wanted to please you. But I settled for this miserable thing.”

It was an elegant tobacco case made of cherry bark he said he’d found on the Ginza. I became envious of the fact that he took so much care in buying such a gift, and that he was able to do that.

“I didn’t buy anything for my family. I brought gifts only for you and Shinroku, and I was scolded terribly. You have to consider our relationships with our neighbors and relatives. . . . My mom scolded me about such a trivial thing as if it was a life-or-death matter.”

Looking weary, his face showed no sign of vitality.

“Adult society is just like that. When I came back here, I resisted and suffered for some time, but I got used to it. Or, rather, I’ve become insensitive.”

“Insensitive, you say. If that’s the way it is, Taiwan can’t change. The hunter becomes the hunted—doesn’t that apply to you, my older brother-in-law?”

“I don’t deny it. Old shells are as hard as you might expect. If you think you can easily break the shell, I’d say that’s because of the youth of your emotion.”

Now I’ve taken root in the red-brick floor,16 but for some time after I returned to Taiwan, I tried to break old shells—that’s what I would have told him.

“The youth of emotion, I see. I’d rather brag that it’s the youth of the spirit,” he struck an arrogant pose.

Then there was a voice, “May I come in?” and with that Taka Shinroku in yukata stepped in.

“We’ve been waiting for you. Did your store close?”

“Not yet. I’ve been on the second floor for some time. Your mom is in a bad mood. If we knew Meiki was going to change like this, we wouldn’t have sent him to Tokyo, she said, cutting you up.”

“Yeah, that must be about gifts. Let her say whatever. Listen, here’s something I bought for you,” he said, and took out a gift that was the same as what he’d given me.

“Is it all right? For me to accept it?”

“I bought it for you. All right or not has nothing to do with it.”

“What is it?”

“A tobacco case. Pretty good, isn’t it?”

Meiki opened it for him.

“Beautiful, but I’m sorry, I stopped smoking.”

“You did? When did you develop such admirable sense?”

“Last June I gave it up completely.”

“Why’s that? You were puffing away since you were under age.”

“No particular reason, but I wanted to test myself. I tried to see to what extent I could control myself.”

“I see.”

“That’s great. No ordinary person can do that.” Drawn into the conversation, I said

“Before that, I’d tried to do the same several times but failed. But, since I joined the Patriotic Youth Corps17 and started experiencing divine human training as ‘deity-human unity,’18 I’ve been able to conquer all evil ideas, personal benefit, personal desire.”

“You mean Nishi Genji19 Sensei’s Patriotic Youth Corps?” I interjected before Taka finished. It was widely known that the Patriotic Youth Corps was an organization for ‘training to become Imperial citizens’ to unify in-land and Taiwanese youths. Many youth from the unit had already joined the military, it was said, but here I unexpectedly was hearing an explanation of the unit.

“How are you members of the Patriotic Youth Corps hand-clapping Shinto-style20 related to the movement to ‘train to become Imperial citizens’?” Meiki asked suspiciously.

“Of course we are closely related. ‘Respect-to-deities-revere-ancestors’ ergo ‘Imperial-citizen thought,’ isn’t that it?” As soon as I said this, Taka Shinroku flushed even further. The way he solidly settled down, his arms held up, indicated that he seemed quite used to this kind of debate.

“That shows your limited understanding. Hand clapping is guided by the deities so we may approach them. You can achieve ‘deity-human unity’ only by praying with ‘divine clarity with supreme sincerity.’ What was called matsuri in ancient times meant this ‘deity-human unity.’ Everything starts with matsuri. You know ‘church-state unity’ is the origin of ‘governing in the Imperial Way,’ don’t you?21 By clapping our hands, we members of the Youth Unit try hard to touch ‘the Yamato soul’22 so we may experience it. This is a divine experience that not all the youth of this island can hope to attain.”

“Hmm,” both Meiki and I groaned and kept silent for a while.

“I didn’t know there was a way like that of ‘training to be an Imperial citizen.’”

“That is not a way. That’s the path we ought to take.”

“That’s the same, isn’t it?” Meiki appeared offended, though soon he laughed spasmodically.

“You mean, you intend to spread the gospel among us.”

“Of course, I hope to do that. The more members we have in the Unit the more progress Taiwan makes, we are convinced.”

“That’s the trouble. I can agree to this as a theory, but it’ll be impossible as an actual case.”

“We reject theories. We can only pray, we can only act. Unless you act, you gain nothing. This belief makes the bonds among us members tighter.”

“I wonder how many can follow this.”

“If you doubt it, come to our dojo and take a look. You’ll convince yourself.”

“I hear you pay respects to a shrine at six every morning.”

Seeing that Meiki visibly showed a loss of interest, I took on a conciliatory role.

“How about going to check the vending booths below the park?”

With that as a trigger, we talked about things like the fact that five-sen soba had disappeared, but I had to try quite a bit before taking the two out for a walk.

Four days after that, on Sunday night, I went with my child to visit Meiki at his house. The third floor of the house was a large tatami-room, which Meiki occupied all by himself. Reflected on the shoji were two shadows in a fierce debate.

“Your ‘deity-human unity’ may be fine, but biased, narrow ideas are not good for the future of Taiwan. I don’t want such things to push us around. I’m scared that Taiwan’s core youth is nurtured by such things. Even now we are a truly itty-bitty race indeed, aren’t we? That’s what you realize yourself painfully, isn’t it? Culturally we’re an extremely low-level race. We can’t do anything about that. We had no education, no training, until now. But, even if ‘training to become Imperial citizens’ is what’s urgently needed at the moment, it’s adequate if we provide what’s been lacking, education and training, as soon as we can, isn’t it? All we have to do is to pull our levels up to those of in-landers, isn’t it? Is it necessary to clap your hands for that purpose?

“You’re talking about nothing more than the cultural problem? But you’re terribly misunderstanding the matter. What I’m talking about is the spiritual problem. It’s the injection of the Japanese spirit.”

“You bring in the Japanese spirit, I see.” Meiki fell onto his back.

“It’s important to inject even more of the Japanese spirit. In Japanese life, no life exists that neglects the National Polity.23”

“Hmm, you’re right about that,” Meiki said, though he hadn’t conceded defeat. “But the injection of the Japanese spirit doesn’t mean something as ‘divinely possessed’ as you might think. A Japanese is what you and I, or probably anyone who has been educated in Japan, can become. In my case, I can definitely tell you that I’ve become completely Japanese. Can becoming Japanese be so hard? I don’t think so. When you bow deeply before the Double Bridge24 and are moved to feel solemn, that’s enough, don’t you think? Bow deeply before the Yasukuni Shrine and feel indescribably moved—that means you are Japanese, does it not? Tears spring up, but they do not come out because you want them out. They come out by themselves, you can’t control them, the tears simply come out. Isn’t that enough? Take any young man nowadays. Take him to the Imperial Plaza. You don’t have to have him bow, he will bow just fine.”

There was a moment of silence. Meiki was seated cross-legged, the lower hem of his yukata tucked up, his thin arms gripping his ankles, and he maintained that posture. His eyes were glaring weirdly.

“Well, then, that means both of you have completely agreed from the start that you become Japanese. If that’s the case, there’s no room for debate, is there?” I said, deliberately playing dumb.

“It’s the methodology,” Meiki’s voice carried the momentum of the passion.

“We had set the same goal before Meiki went to Tokyo,” Shinroku said. “We had agreed before our debate that our goal remains the same now, there’s no mistake about it, but what’s confused us is the path to reach that goal. Meiki began to claim that my way of doing it is ‘divinely possessed.’”

“You accused me by saying I’m a follower of Judaism, that I’m Western-infatuated, didn’t you?”

“Meiki, you are saying something like this. You’re saying that for ‘training to become Imperial citizens’ we must first improve our culture, improve our life. For that, you’re saying that we must accept other things more widely, with a greater sense of freedom, aren’t you?”

“I’m not talking about anything like freedom,” Meiki corrected me. “But Shinroku is misunderstanding this. I am agreeing that Taiwanese culture should be one of the regional cultures of Japan. Except that the way he talks, Shinroku sounds so ‘divinely possessed’ that my head can’t accept it.”

I kept silent awhile, sorting out my uncertain, wild surmises. I thought I understood what was in Meiki’s head that made him say, “Your head can’t accept it.” But I understood that what Shinroku was thinking was better organized.

“I can’t help it if with your ‘all-scientific’ head you call me ‘divinely possessed,” Shinroku said. “But by clapping our hands we are living a faith. It’s a question of faith. It’s a faith that we can become Japanese.”

“That you think you can’t gain that faith without clapping your hands, that’s what my head can’t accept.”

“No, that’s not it. If it’s Japanese faith, that’s born by clapping your hands. We clap our hands when we accept a meal. We clap our hands when we go into battle.”

“Hmm. ——But,” Meiki closed his lips firmly. But he didn’t look defeated. It belongs to the question of subtle emotion you can’t express with the weapon called language. This shade of emotion can’t be understood except by the person who had it. No matter how hard other people might try, they wouldn’t be able to wipe it away. Meiki clung to the word “But,” and wouldn’t let it go, because, I imagined, he was entangled in this lovely feeling of his.

“But——I can’t stand the way you make it so ‘divinely possessed,’” he said, spitting the words out, again falling onto his back.

But the following day, when I was alone adjusting accounts in my store, Meiki walked in, rather casually, clutching in one hand the monthly magazines I’d taken to him.

“I see, you rarely come to me like this.”

He grinned awhile. Then, with the air of someone stubbornly unwilling to disclose something, he shopped around the shelves of my store for some time. Finally, he sat down with a thud on the chair in front of my desk, and said, “I ran away. Shinroku came again. He’s bothersome, so I sneaked out.”

“That’s rude to him. It’s no good to abandon your friend in debate.”

“No, I don’t mean to abandon him. I just got away from him. We don’t jibe in our talk, you see. He starts running blindly like a hoodwinked fool. That’s what I can’t stand. He says single-mindedly ‘Japanese,’ ‘the Yamato soul.’ He doesn’t take any criticism at all. I can’t stand that.”

“Even so, you too say ‘Japanese,’ ‘Japanese.’”

“True, we’ve got to become Japanese. But unlike him, I don’t want to be like a horse saddled with a carriage. Why do we have to become Japanese? That’s the question I ask first. I was in Japan. I grew up with education in Japan. I cannot speak anything but Japanese. I can’t write letters unless I use Japanese kana. That means I have no meaning in living unless I become Japanese.”

Meiki said this in one breath. When I heard it, I was suddenly struck by a thought. So that was what he was thinking. That was why he set a goal but had to suffer—I had an oddly ironic feeling.

“You calculate closely. What you got out of all that was the goal you set.”

“No, I had set my goal before all that.” Meiki showed a faint smile and quickly looked down.

“You mean you did all that calculation after you went to Tokyo. I’m surprised.”

“To tell the truth, I’m surprised myself.”

He maintained his faint smile. But that smile was now a shrewd one. As I watched him, I thought truly that he was a weak-willed person. Without being able to dash toward the goal he set, he was distracted all the time, against his will, because of that calculation. But there was something you couldn’t clearly explain about that calculation, too. That was because, as he said himself, he had grown up as a Japanese since birth. No, even before he was born, he was fated to be one. He unhappily calculated that fate on the intellectual abacus he got in Tokyo. Was that the tightrope trick I had expected—was that the expectation, however vague, I had for him when I parted with my Tokyo life eight years ago, a sentimentality that had not disappeared even now?

As the electric light hit the bare wall of red bricks, I felt suffocated.

I couldn’t make any progress in adjusting accounts as long as he was with me, so I chased him up to my older sister on the second floor. He went up to the second floor obediently. The noise he made on the absurdly high staircase resounded through the house, and a terrible loneliness assaulted me.

Just about ten days later, I was startled when reading the morning paper after breakfast.

Volunteer application with blood oath: Mr. Taka Shinroku—that headline was in No. 5 point type.

Grabbing the paper, I at once hurried to Meiki’s house. A few houses before his, I caught up to him. He rarely got up so early.

“Did you know Shinroku applied to be a volunteer with a blood oath?”

“Just been to him. I’m coming back just now. What an extraordinary thing he did.”

We entered his house in silence. His face showed a lack of sleep but also excitement; he took a breath.

“I went to Shinroku to apologize. He’s ahead of me. Shinroku is the one who will move Taiwan for Taiwan’s sake. I am after all a powerless human being who can do nothing for Taiwan. My head is too big. I told him that. He had finally persuaded his 67-year-old mother and submitted a volunteer application yesterday. He hadn’t told me anything about this before he submitted the application. He cut off his little finger.25 I can’t do anything like that. Like a man. I went and bowed to him.”

“You’ve got something good about yourself, too,” I said, without meaning to tease him.

“From now on, I’ll totally remake myself. So, older brother, back me up.” In a shrill voice, Meiki seemed to struggle to crush something hot that was coming out of him.

His staircase was too narrow for both of us to walk up side by side so I walked behind him. He was tall. With him blocking the way, it was dark, and I climbed, as if counting each step, choosing the lighter spaces.

Slowly going up like that, the staircase was quite long.

Notes

This annotated translation is an expanded and revised version of Hiroaki Sato’s translation of “The Volunteer,” first published in 2016 in Taiwan Literature: English Translation Series no. 37 (eds. Kuo-ch’ing Tu and Terence Russell).

Following the 1919 revision of the education laws, junior high school 中学校was set at five years for those who finished elementary school (those beyond age 12).

公学校Established in 1898 to teach Taiwanese children Japanese. In 1923, the law was revised to teach the same subjects as in Japan. It corresponded to the 6-year elementary school小学校. In 1941 the laws were further revised to merge the schools for the Taiwanese with those for the Japanese, calling both kokumin gakkō, “people schools,” imitating the German Volksschule.

The education law revised in 1907 changed the 4-year ordinary elementary school 尋常小学校and 4-year higher elementary高等小学校to a 6-year ordinary elementary school and 2-year higher elementary school.

国語kokugo, “national language,” that is, Japanese, to distinguish it from gaikokugo, a “foreign language,” in this case Chinese.

専門学校. Also translated as “vocational school.” So called because such a school was dedicated to one “profession,” such as medicine, law, or commerce. It would correspond to today’s college or university.

During the period when Japan had colonies and other territories, the Japanese distinguished between naichi, “in-land,” referring to Japan proper, and gaichi, “out-land,” overseas, referring to all the rest.

皇民化錬成kōminka rensei. Kōminka meant “turning (Taiwanese) into Imperial citizens,” which today may be called “Japanization,” and rensei, “training,” “drilling,” a word with some religious overtones. At the time Japan was under “the emperor system.” Under the system, all Japanese could be called kōmin, “the emperor’s subjects,” which led to the idea of extending the term to the peoples in Japan’s colonies, hence kōminka. The term was officially promoted by Governor-General Kobayashi Seizō (1936-1940) in 1939 as one of the “three main policies”: kōminka, (further) industrialization, and turning Taiwan into a base for Japan’s expansion to the South Seas. It included prohibition of the use of the Chinese language in newspapers, promotion of changing names into Japanese-sounding names (see next footnote), promotion of respect for Shintoism, and promotion of the use of the Japanese language at home and adaptation of the “Japanese way of living,” such as tatami, shoji, and other aspects of Japanese housing.

改姓名kaiseimei, “name reform,” that is, changing names to sound and look like Japanese names. Because of Chinese influence following a brief period of Dutch rule in the mid-seventeenth century, most Taiwanese had Chinese names.

Soldiers seriously wounded in battle, who, after being hospitalized, were often out on the streets begging for money in Japan, and, apparently, in Taiwan as well. These men usually had no relatives who could care for them.

The Government-General of Taiwan built a red-brick cigarette factory behind Taipei Station, in 1911. 陳柔縉『日本統治時代の台湾』 (2014), pp. 131-145.

Full name, 勤行報国青年隊 Kingyō Hōkoku Seinentai, Devotional Patriotic Youth Corps. In the 1920s the Government-General of Taiwan started promoting the formation of “youth units” (seinentai) in municipalities for social education that included religious, spiritual (Shintoist) elements. During the latter half of the 1930s, as Japan intensified its war in China, the Taiwanese GG strengthened militarization of these units. The Devotional Patriotic Youth Corps was the result. 宮崎聖子:植民地台湾における青年団の変容

神人一致shinjin itchi. This idea was put forward and emphasized with the restoration of the emperor to his ancient status in the second half of the 19th century. A similar idea was also promoted by people like Deguchi Onisaburō (1871-1948), one of the founders of the religious sect Ōmoto-kyō. The Japanese government, regarding it as a pseudo-Shintoism detrimental to the Emperor System, tried to suppress it by persecuting members of the sect.

The word まつり matsuri originally meant both “rite” (festival) and “government,” with the emperor being the supreme human embodiment of kami to undertake both. Later, two different Chinese characters came to be applied to differentiate the two:祭 sai (Japanized pronunciation of Chinese ji) and政 sei (Chinese zheng), hence the later phrase祭政一致 saisei itchi, “unity of church and state.”

大和ごころYamato gokoro, similar to 大和魂Yamato damashii, “Yamato spirit.” Yamato started out as the name of a small area of what today is known as Nara, but later it became the symbol of all of Japan. Around the 11th century, Yamato gokoro meant something like “Japanese (indigenous) talent” as opposed to “Chinese talent.” This idea easily turned into something chauvinistic later.

国体Kokutai. Central theme emphasized by Neo-Confucianists toward the end of the Edo Period (1603-1868) developed the term, which at the time connoted a special emperor-based state; in the 1930s it came to connote a sacred, inviolable state.

二重橋Nijū-bashi. It is the iron bridge at the entrance to the Imperial Palace. Often, the stone bridge spanning the moat next to the Imperial Palace Plaza is mistaken for the one so called. In prewar Japan, the bridge became the embodiment of the emperor.

The act of severing one’s own little finger with a knife (or a sword) has been known, in recent years, as a custom among yakuza to show contrition or pledge solidarity with a group. A blood oath usually takes the form of wounding one’s finger to draw blood.