Abstract

This article reviews the potential for United States accession to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) under the current U.S. leadership, the administration of President Donald J. Trump and the Republican-controlled Congress. The strategic significance of U.S. ratification of UNCLOS is demonstrated by U.S. claims and rights in areas subject to geopolitical contestation such as the Arctic and South China Sea. More broadly, the United States has a compelling interest in preserving the international order and protecting the global commons, as embodied in the terms of the treaty. Despite clear evidence that ratification is in the U.S. national interest, UNCLOS faces the obstacle of continued Senate inaction and the challenge of a domestic political atmosphere suspicious of international law and institutions. President Trump, as a Republican leader and populist dealmaker, may be well-positioned to overcome domestic political opposition and achieve a vital U.S. foreign policy objective that has eluded his White House predecessors.

Key words: UNCLOS, International Law, Treaty, Donald Trump, South China Sea, Arctic, Global Commons, Territorial Conflicts

When at the steps of the Louvre, turn your gaze toward Rue de Rivoli, to a work of Parisian art, the Palais-Royal (originally the Palais-Cardinal), the former residence of Cardinal Richelieu. Richelieu is credited with articulating the principle of raison d’État, the national interest, as a transcendent entity, an ideal above and beyond the private concern of statesmen. As Louis XIII’s chief minister, during the religious wars of the 17th century, he rose above confessional loyalties, allying Catholic France with Protestant powers in order to maintain the European balance of power. In the Testament Politique, Richelieu’s political manual, he observed: “The public interest must be the sole end of the prince and his councilors.”

In Washington today, we have fresh opportunities to assess the raison d’État as defined by the current U.S. leadership: the new Trump administration and a Republican-controlled Congress. One significant measure will be whether the United States finally ratifies the United Nations Law of the Sea Convention (“UNCLOS” or the “Convention”), the comprehensive treaty regime that governs activities on, above and below the world’s oceans. Although the United States was an original architect of the treaty, Senate advice and consent to ratification has remained stalled through three successive presidential administrations. For more than 20 years the national interest has fallen victim to the confessional nature, the hardened doctrinarism, of modern American politics.

Now a powerful tide of populism has swept over the banks of the Potomac – one that is suspicious of globalization, international law, and technocratic bodies. A heightened sense of nationalism is threatening to contract Washington’s view of the global order and the United States’ role therein. The recent U.S. withdrawal from international agreements involving global trade and climate change is symptomatic of this dynamic. In this context, can Congress elevate the national interest above narrow partisan aims? Will President Donald J. Trump exercise the necessary leadership to realize an objective that has eluded his White House predecessors? Only Washington can address these questions. Make no mistake, though, the answers will have a global ripple effect, from the melting plates of the Arctic Ocean to the choppy waves of the South China Sea.

From Insider to Outsider

Following nearly a decade of negotiations, UNCLOS was completed on December 10, 1982 at Montego Bay, Jamaica. Even at that time, the United States refused to sign the treaty. This despite the fact that America was the largest beneficiary in terms of territorial gains under the newly codified regime. The United States, along with other industrialized states, took issue with aspects of the treaty (Part XI), which dealt with deep seabed resources beyond national jurisdiction. Largely at Washington’s instigation, negotiations continued and resulted in the Agreement relating to Implementation of Part XI of the Convention (1994 Agreement), completed in New York, July 28, 1994.

Determining that the remaining deep seabed issues were resolved, on October 7, 1994, President Bill Clinton transmitted the Convention and the 1994 Agreement to the Senate for advice and consent. On November 16, 1994, UNCLOS entered into force, but without accession by the United States. The 1994 Agreement entered into force on July 28, 1996, also without U.S. ratification. To date, the treaty remains one of forty-five treaties (one dating back to 1945) awaiting Senate action – an institution once referred to as the “world’s greatest deliberative body.”

As a result, the United States remains off the list of 168 state parties to UNCLOS, a list which includes all other major maritime powers such as Russia and China. In practice, the United States has accepted and complies with nearly all the treaty’s provisions (though it is formally bound by none).

For example, on March 10, 1983, President Ronald Reagan relied upon UNCLOS when issuing Proclamation 5030 establishing the U.S. exclusive economic zone (EEZ) in the Atlantic, Pacific and Arctic. The U.S. EEZ is the largest in the world, spanning over 13,000 miles of coastline and containing 3.4 million square nautical miles of ocean—larger than the combined land area of all fifty states, according to the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. On the same date, President Reagan also issued the United States Oceans Policy Statement, supported by National Security Decision Directive 83, which documents the U.S. view that UNCLOS reflects customary international law and fulfils U.S. interest in “a comprehensive legal framework relating to competing uses of the world’s oceans.” Successive presidential administrations – Republican and Democrat – have relied upon Reagan’s precedent to codify U.S. EEZ claims and legitimize the Freedom of Navigation (FON) Program in global hot spots like the South and East China Seas.

So even as the United States invokes UNCLOS to proclaim broad territorial gains, assert the freedom of navigation, and challenge excessive maritime claims, Washington has no seat at the table in protecting U.S. rights and claims within the treaty’s institutional framework. As a non-party, Washington remains on the outside looking in as the international community moves forward in defining the legal landscape affecting over 70 percent of the world’s surface.

Identifying the National Interest

To the extent that the United States relies on custom, as supported by power, to protect its interests, there are material benefits to free riding from the UNCLOS regime. As I have noted elsewhere, however, the law of the sea has not followed a linear progression and customary international law is subject to variance and contestation. Moreover, arguments against accession ignore the significant costs that the United States has incurred and continues to pay by remaining a non-party. Put another way, in determining the national interest, we have to fully account for the material advantages provided by accession to the Convention.

Ratification will give the United States a direct voice in UNCLOS bodies like the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf, and the International Seabed Authority. For instance, at a recent gathering at the American Society of International Law (ASIL), Douglas Burnett, a maritime attorney and advisor to the International Cable Protection Committee, explained that, in the current landscape, U.S. telecommunications companies are forced to seek foreign state sponsors to voice their concerns in UNCLOS disputes over undue interference by coastal states to the freedom to lay undersea cables. An estimated 98 percent of worldwide internet data is transmitted through the web of fiber optic cables lying on the ocean floor, which are the arteries of the global economy, and, therefore, a significant U.S. concern.

In addition, UNCLOS reflects traditional U.S. policy with respect to living marine resource management, conservation, and exploitation. For example, from within the treaty, the United States can more effectively exert its leadership in managing depleted fish stocks, which migrate internationally across maritime zones and the high seas. Organizations as disparate as the World Wildlife Fund and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce have strongly supported U.S. accession. According to John Norton Moore, director of the Center for Oceans Law and Policy at the University of Virginia, since the U.S. already follows the treaty, the costs of compliance are insignificant, particularly when weighed against the U.S. capacity to influence institutional development in global maritime policy.

More broadly, the UNCLOS regime is part of the bedrock of the U.S.-led liberal order. As G. John Ikenberry argued in After Victory, since the Congress of Vienna, leading states have employed institutional strategies as mechanisms to establish restraints on arbitrary state power and embed a favorable and resilient international system. In this instance, the Convention and 1994 Agreement were negotiated during a time of U.S. ascendance and Western unity in international affairs. At ASIL, Myron Nordquist, Associate Director of the Center for Oceans Law and Policy, articulated how UNCLOS reflects important U.S. interests regarding restraints on economic exclusive zone, continental shelf resources, innocent passage across the territorial waters, the passage rules for transiting straits and archipelagic sea lanes, and, of course, the high seas freedoms. U.S. ratification will serve to “lock in” these advantages affecting the global commons, and negotiated by the United States from a position of primacy in world affairs.

The strategic necessity of preserving U.S. national interests via accession to UNCLOS is most evident in the evolving waters of the Artic and South China Sea.

The Arctic and the South China Sea

Climate change is heating up the race for the Arctic as receding sea ice gives way to increasing human activity. In addition to advancing new sea lanes, nations bordering the Arctic Ocean are seeking to develop offshore resources, particularly in the energy sector. UNCLOS (Part VI) gives the coastal state sovereign rights over the resources of its continental shelf. The Convention also permits a coastal state with a broad continental margin to establish a shelf limit beyond 200 nautical miles based on specifically defined criteria under UNCLOS (Article 76) that take into account the geophysical characteristics of the seabed and subsoil. Any such claim to an extended continental shelf is subject to the review and recommendations of the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf. The five Arctic coastal states – the United States, Canada, Russia, Norway, and Denmark (via its Greenland territory) – have made or are in the process of preparing submissions to the commission.

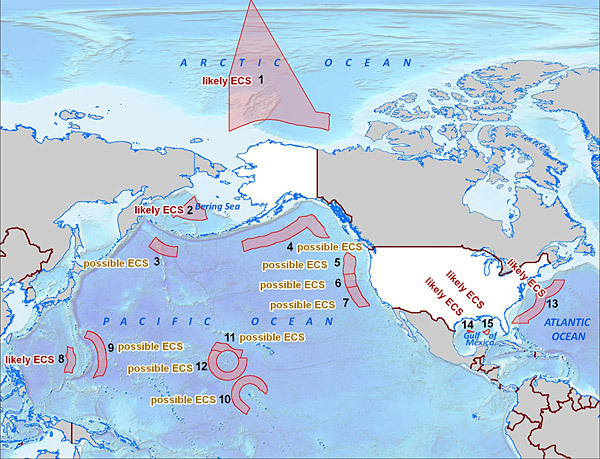

|

U.S. Extended Continental Shelf (ECS) Map |

According to the U.S. Extended Continental Shelf Task Force, an interagency governmental body, preliminary studies indicate that the U.S. extended continental shelf is at least one million square kilometers – an area about twice the size of California. The United States has extended continental shelves in several offshore areas, including in the Arctic Ocean north of Alaska, the Atlantic East Coast, the Bering Sea, Pacific West Coast, and the Gulf of Mexico.

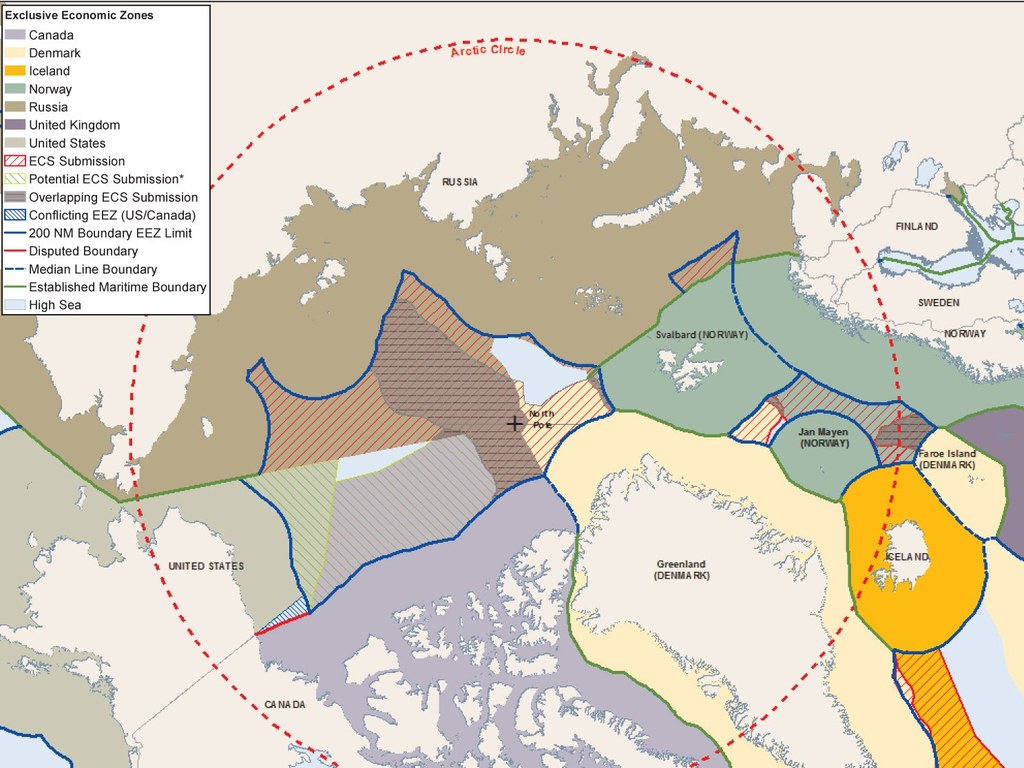

Given that the United States has not ratified UNCLOS, however, U.S. nationals may not serve as members of the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf. It is not clear whether the United States, as a non-state party, can even make a legally recognized submission to the commission to assert its claim and fully protect its proprietary rights and energy interests such as in the Arctic. In contrast, Russia, which may be entitled to almost half of the Artic region’s area and coastline, has already made its submission for vastly extending its continental margin, including a claim to the Lomonosov Ridge, an undersea feature spanning the Arctic from Russia to Canada. Russia and Canada are the two countries with which the United States has potentially overlapping extended continental shelf claims.

This maritime boundary dispute is no small matter. The U.S. Geological Survey estimates that the Arctic holds 22 percent of the world’s undiscovered oil and gas, amounting to more than 412 billion barrels of oil equivalent. Legal certainty in maritime delimitation is critically important for Arctic states and their respective energy companies. On June 8, 2012, Rex Tillerson, as chairman and CEO of ExxonMobil, wrote to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee to vociferously urge U.S. accession to UNCLOS:

“Perhaps the best example of the need for certainty in an area with great unexplored potential involves the Arctic Ocean…Several countries, including the United States, are provided with a claim to extended exploitation rights under the application of UNCLOS in the Arctic. The legal basis of claims is an important element to the stability of property rights.”

In the absence of treaty ratification, Tillerson noted that the United States suffers from the dual disadvantage of having both a cloud over the international status of U.S. claims and a weakened ability to challenge other states’ conflicting claims.

|

Arctic National Boundary Claims Map |

As a sovereign state, the United States can object to overlapping claims and take action in the Arctic consistent with international law. Awkwardly, however, arguments against UNCLOS ratification must turn to support from the International Court of Justice, which has ruled (Nicaragua v. Columbia, 2012) that continental shelf rights exist as a matter of fact and do not need to be expressly claimed. Even if custom provides one remedy, a contract is better than a handshake – more so in a world of power and interdependence. Moreover, the Arctic coastal states, including the United States, have positively affirmed that the law of the sea provides the “legal framework” for resolving overlapping territorial claims. Intergovernmental bodies like the Arctic Council, while useful for multilateral cooperation, lack authority for resolving territorial conflicts. As the future secretary of State, Tillerson, wrote to the Senate: “UNCLOS can provide an efficient, comprehensive legal basis for the settlement of these conflicting claims, thus providing the stability necessary to support expensive exploration and development.”

The South China Sea is another area of heated contestation where UNCLOS serves as the guidepost for clarity. Of notable importance is the ruling from the South China Sea arbitration that UNCLOS comprehensively allocates rights to maritime areas thereby precluding historic claims like China’s “Nine-Dash Line.” From this principle, the arbitral tribunal systematically refuted China’s extensive claims and actions in the South China Sea beyond the treaty’s carefully crafted limitations. In the view of Washington, these limitations include undue attempts to curtail the freedoms of navigation and overflight in EEZs. Notably, China takes an opposing view and asserts the ability to prohibit foreign military operations in its claimed EEZs. Thus, although, in the past, the United States has officially remained neutral on competing claims in the South China Sea, Washington has a compelling national security interest in upholding the substance of the arbitral tribunal’s ruling.

Like U.S. claims in the Arctic, the United States’ legal rights in the South China Sea are not academic. As reported by Ronald O’Rourke, a U.S. naval affairs analyst, the EEZ legal dispute between Washington and Beijing has led to significant confrontations between Chinese and U.S. ships and aircraft in and above international waters. For example, in August 2014, a Chinese J-11 fighter dangerously intercepted a U.S. P-8A Poseidon, a naval reconnaissance aircraft, operating in the South China Sea approximately 117 nautical miles east of Hainan Island. Beijing has repeatedly attempted to link security prerogatives with the functional jurisdiction of maritime zones, like EEZs, by limiting high seas freedoms, even to the extent of threatening unduly restrictive aircraft defense identification zones (ADIZs) in international airspace. Thanks to the arbitral tribunal’s artful debunking of the nature of Chinese-claimed maritime features and related entitlements, there is greater legal clarity on U.S. operational rights in the South China Sea. For instance, although some Chinese-claimed features are entitled to a territorial sea (12 nautical miles) none of the features in the Spratly Islands or Scarborough Reef generate an EEZ (200 nautical miles) or continental shelf. By formally joining UNCLOS, the United States will be in a stronger position to support the ruling of the arbitral tribunal in the face of opposing action from China.

|

South China Sea Arbitration, Maritime Entitlements Map |

More broadly, because substantial portions of the world’s oceans are claimable as EEZs, universal adoption of the Chinese position would significantly alter the U.S. military’s ability to sail and fly worldwide. These debates over high seas freedoms and EEZs are likely to continue. For example, as I wrote in the Harvard National Security Journal, the so-called “Castaneda formula” under UNCLOS (Article 59) opens the door for further articulation of EEZ functional jurisdiction and any potential limitation on the high seas freedoms. Under this formula, a diplomatic compromise, in cases where the Convention “does not attribute rights or jurisdiction to the coastal State or to other States within the exclusive economic zone,” any conflicts regarding EEZ functional jurisdiction should be resolved on the “basis of equity” and in light of “all the relevant circumstances, taking into account the respective importance of the interests involved to the parties as well as to the international community as a whole.” Defining the so-called “residual rights” of states requires interpreting what rights are included in the treaty’s text as well as what rights are omitted. The United States can more effectively anticipate and shape these debates impacting U.S. national security as a state party to UNCLOS.

|

EEZ Claims World Map |

In a twist, U.S. opponents of ratification may view the South China Sea case as supporting their position for remaining outside of UNCLOS. One of Beijing’s chief objections was that the arbitral tribunal should not have intervened, arguing that the dispute essentially involved delimiting maritime boundaries, which would fall outside compulsory dispute settlement pursuant to a declaration China made under UNCLOS (Article 298(1)(a)(i)). As I explained previously, the arbitral tribunal was careful to limit its discretion to determining whether certain Chinese-claimed features – particularly in relation to the Spratly Islands and Scarborough Shoal – could generate maritime entitlements as high-tide features.

The arbitral tribunal, however, could have declined to even rule on these issues in light of the impact an analysis on maritime features and entitlements would implicitly have on Chinese boundary claims. By analogy, under the U.S. legal system, courts defer certain “political questions” because the matter is considered unsuited to judicial inquiry, and more constitutionally appropriate for settlement by the political branches. While the arbitral tribunal may have been technically correct on the legal merits in the case, UNCLOS faced a greater institutional harm if China had followed through on Beijing’s threat to withdrawal from the treaty. The fact that China did not withdraw suggests that the balance of interests favored continued participation in UNCLOS, a calculus that could further tilt as Beijing advances its blue-water navy.

U.S. critics of UNCLOS may perceive the South China Sea scenario as prime evidence of meddling by an international court. Myron Nordquist offered a hypothetical in which the United States ratifies and submits a similar declaration, but in relation to excluding disputes over military activities from compulsory dispute settlement (Article 298(1)(b)). Despite such a declaration and U.S. objections, an international tribunal may attempt to intervene in a dispute where another state party challenges U.S. FON operations in its EEZ. Other potential controversies could include revisiting U.S. EEZ claims in the Pacific – for example, in relation to Howland and Baker Islands, Jarvis Island, Johnson Atoll, or Palmyra Atoll and Kingman Reef – based on the arbitral tribunal’s analysis of rocks and islands in the South China Sea. Even if you believe that such fact patterns seem improbable, American opponents of UNCLOS and international law may seize upon the South China Sea arbitration as a dangerous harbinger.

During his confirmation hearing, Secretary Tillerson backed away from his 2012 letter, acknowledging domestic critics of international courts. General James Mattis was similarly circumspect before the Senate. Even the abstract threat of international court jurisdiction results in theatrics in American politics. To recall, in response to the Rome Statute, Republican Senator Jesse Helms sponsored the American Service-Members Protection Act, which was affectionately called the “The Hague Invasion Act.” There are those in Beijing that may share the late senator’s sentiments.

The Domestic Trump Card

For a White House under siege, UNCLOS ratification may present an opportunity for a specific foreign policy achievement. After all the United States is engaged in an unequal bargain: adhering to the terms of UNCLOS without enjoying the benefit of shaping the treaty’s rules or institutions. But the Trump administration has already demonstrated a clear penchant for withdrawing from international agreements – such the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a multilateral trade agreement, and the Paris Agreement, a global climate accord. As noted above, the Congressional nomination testimonies of Secretaries Tillerson and Mattis provide little comfort. If the Trump administration were to oppose UNCLOS ratification it would be a remarkable and deplorable break in bi-partisan presidential leadership.

Even assuming the Trump administration’s support, accession will not come easily. According to a Congressional report, in the course of U.S. history, only 1,100 treaties have been ratified in comparison to over 18,500 reported executive agreements. Senate inaction has proven to be a very effective veto. Even treaties that flow from American leadership, in areas like protecting rights for persons with disabilities, are rejected. As such, treaty ratification would be a monumental (and surprising) legacy-builder for Trump.

Global frameworks like UNCLOS are also exceptional events in international affairs. Advocates and opponents of U.S. accession both acknowledge that the terms of UNCLOS would be impossible to negotiate today. In my view, this reality demonstrates the wisdom of locking-in U.S. gains and the importance of establishing international institutions capable of maintaining validity in a changing geopolitical environment. Treaty-making and diplomacy require a certain “suppleness,” to borrow from Ruth Wedgwood, Professor of International Law and Policy at the John Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies. U.S. participation could strengthen UNCLOS by ensuring that new life is breathed into the document’s text, consistent with U.S. interests.

Unfortunately, the contemporary political environment is characterized by a rigidness and polarization that defy supple solutions for U.S. accession to UNCLOS. The current populist strain is characterized by a faith in strong leaders, a disdain of perceived limits on sovereignty and a distrust of powerful international institutions. Criticism of international law has taken on a religious fervor, become an emotional calling. The South China Sea case may only prove the ideological point of detractors of international legal regimes like UNCLOS, no matter how shortsighted.

As I have argued before, preserving the international order and protecting the global commons is an important means for putting “America first.” Whether navigating the world’s oceans, piloting international airspace, or browsing the World Wide Web, U.S. influence is demonstrated by and promoted under this rules-based order. The global regimes America helped construct not only have supported historic gains in global wealth (with nearly a billion people lifted from absolute poverty over the last 30 years), but also have provided for the power and affluence that the United States and its citizens enjoy today. This has not been a zero sum game for America. Moreover, the international community and the United States, especially, would find new and significant transaction costs if Washington withdraws from the world’s governing institutions. Relying on rising powers like China to steer the course of global politics, a role Beijing increasingly relishes, is a gamble that a former casino owner like Trump may appreciate.

Perhaps in this Trump era, only a figure like Donald J. Trump can lend legitimacy to a complex global undertaking that is in the U.S. national interest. The Republican-controlled Senate is unlikely to act without political cover from the White House. In other words, a Republican leader and populist dealmaker may be required to overcome the trump card of domestic politics in this vital area of U.S. foreign policy. This scenario will require decisive presidential leadership and a clear view of the national interest in Washington.

If Richelieu were able to roam the halls along Pennsylvania Avenue, would his Red Eminence be able to find what he described as the “torch of reason” – the light that must guide the conduct of princes and their states? During the Thirty Years’ War, the stakes were high and politics unforgiving, but Richelieu’s vision of the raison d’État provided grounds for a future Westphalian peace. He observed that while authority constrains obedience, reason captivates it. Fortunately, we need not resort to hypotheticals to assess U.S. leadership and the national interest in the Trump era. Whether the United States ratifies UNCLOS will provide us the measure we seek.

Roncevert Ganan Almond is Partner and Vice-President at The Wicks Group, based in Washington, D.C. His practice is devoted to U.S. regulation and policy, international law, and government relations involving aviation, aerospace and national security matters. He has advised the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission and governments in Asia, Europe, Africa, and Latin America on issues of international law. Mr. Almond serves as a contributor to The Diplomat, a current-affairs magazine for the Asia-Pacific, and editorial board member for The Air & Space Lawyer, the publication for the premier association of U.S. legal practitioners in the field. In addition, he has written extensively on international affairs and national security for publications such as the Harvard National Security Journal, Columbia Journal of Transnational Law, and Fletcher Forum of World Affairs. This article is expands upon “U.S. Ratification of the Law of the Sea Convention: Measuring the Raison d’État in the Trump Era,” The Diplomat, April, 25, 2017.