Portions of this essay were previously published in Japanese as 「アジア太平洋戦争のポリティックスと教育―アメリカ合衆国で日本史を教えて」『歴史学研究』942号、2016年3月 (by Jordan Sand and Franziska Seraphim)

In spring 2015, I participated in the drafting and distribution of the statement on the “comfort women” and Japanese war responsibility issued under the title “Open Letter in Support of Historians in Japan.” That letter took inspiration from a statement issued in Japan by the Historical Science Society (Rekishigaku Kenkyūkai) in October 2014 and built on a letter published in March 2015 in the American Historical Association’s magazine Perspectives condemning the Japanese government’s effort to suppress passages about the comfort women in a US-published world history textbook.

At the annual meeting of the Association for Asian Studies in Chicago (held in March 2015), a group of us discussed writing a letter of support for our Japanese colleagues’ efforts to counter the escalating campaign of denial by right-wing politicians and media. After a month of drafting and discussion by email, this resulted in the “Open Letter,” signed by 187 scholars of Japan and sent first to the Historical Science Society, the Historical Society of Japan (Shigakkai), the listserv H-Asia (May 5, 2015), and the Japanese Cabinet Communications Office, then shortly afterward posted in the Asia-Pacific Journal and released to major news media in the United States and Japan as well as wire services.

Most of the signers in the first group of 187 were teaching at universities in North America, but during the week after the Letter’s initial release, roughly 360 more supporters signed, many of them from Europe. We chose not to seek signatures in East Asia in order to represent a voice from outside the countries of the perpetrators and the victims in the comfort women case.

The mass media in Japan gave the Open Letter far greater attention than we had anticipated. The Asahi Shinbun, which had been attacked for its reporting on the comfort women issue not only by right-wing media but by the Prime Minister himself, took this letter, whose signers included prominent Euro-American intellectuals, as a life-line, publishing the full text and the list of signers together with a front-page article about the letter. In the midst of a libel suit, former Asahi reporter Uemura Takashi, who in 1992 had been the first journalist to report a comfort woman’s testimony and had become the target of hate speech and death threats in 2014, told me that he carried the letter to court with him “like a talisman.”

The letter was analyzed, criticized and praised, and its “true meaning” speculated about. Our basic intent, however, was simply to express solidarity with colleagues in the Historical Science Society and others in Japan who had worked to gather testimony and documentation of the comfort station system organized under the Japanese military. We had made a choice not to single out any individual or organization either to support or rebuke. This vagueness exposed us to some misinterpretation and some legitimate criticism.

When historians speak out on a politically charged issue, we are compelled to choose words strategically, calculating their effect rather than simply how accurately we believe they represent historical reality. This mode of rhetoric, which is at the very heart of politics, is ordinarily anathema to our intellectual identities as historians. Indeed, almost everything about the issuing of a statement like this runs against the grain of our usual habits as scholars. In order to win wide support, one must compromise and dilute one’s language; in order to have an impact, one must suppress nuance and complexity; and in order to get published in the newspapers, the statement has to be short. The consensus-based drafting process, although a healthy one, contrasts with the individual pursuit of truth most of us would like to believe we are engaged in as researchers and authors.

Publishing the letter was itself a strategic choice. We knew that it would be widely read if it were signed by certain prominent people. We were, in effect, taking advantage of the fact that Western scholars, and particularly a few well known American “Japan hands,” have unusual influence in Japan. Some people saw a colonial relationship at work here. As one colleague in Japan put it, the media attention to our letter put progressive Japanese scholars in a “double bind,” because they wanted government policy to be influenced by a message like this but did not want it be influenced because the message came from Westerners—particularly not because it came from Americans.

In fact, our standing on the issue could easily have been questioned. We offered no new evidence and clearly could not speak about it with greater expertise than the Japanese and Korean scholars who had researched it most deeply. We could only say that we knew the research on the subject; that we were concerned about the recent tendency in Japan to minimize its seriousness or deny outright that wrong had been done; and that we supported the scholarly findings of those who had shown Japanese state responsibility. Most of the effort in writing the document went into finding a way to express these opinions fairly, without appearing to be speaking from a position of superior knowledge or moral righteousness.

The objections to our statement fell into three categories, generally representing the Japanese right, the Japanese center, and what could be called the postcolonial left, both in Japan and elsewhere. The dominant response of the Japanese right was that we had no evidence and were speaking only from anti-Japanese sentiment. The centrist objection was that although much of the statement was reasonable on the face of it, other countries—especially the United States—had done things just as bad, and we were therefore hypocritical to be rebuking Japan. The postcolonial leftist objection came as much from colleagues in North America as from Japanese colleagues. It asserted that we were denying the complicity of our own field of Japanese studies in U.S. hegemony and in the U.S.-Japan alliance, which had supported conservative rule in Japan and prevented issues of colonial responsibility from being justly resolved.1

There is an element of validity in each of these criticisms. Critics on the right are not mistaken to say that the evidence concerning the comfort women system is fragmentary. This, however, is no less true of many other cases of wartime atrocities, including even the Armenian genocide—the very first mass killing in history to be called “genocide.” Yet in each of these cases, careful historians eschewing nationalist bias have shown that the archival and testimonial evidence is sufficient to describe the incidents as atrocities for which the state bore responsibility. It is possible that some signers of our Open Letter were disposed to believe the worst about wartime Japan regardless of the evidence. But the overwhelming majority of the signers, like most Western scholars of Japanese studies, had intimate personal connections to Japan, so labeling the group “anti-Japanese” misrepresented the character of the community of Japanese studies scholars.

The Japanese centrist criticism that it is hypocritical to sweep others’ doorsteps before you sweep your own is commonsensical. Yet since many of the scholars who signed the document are equally active critics of the United States, particularly on issues of war responsibility such as the atomic bombings and firebombings of Japanese cities, in this instance too the critics had a mistaken picture of the group behind the letter.

The postcolonial leftist criticism is the subtlest and most difficult to adequately rebut. It raises the question of how scholars—any scholars—should deal with their own situatedness, including the positions of privilege that they occupy and the national or imperial structures that support them. In this sense, it can be taken as fundamentally rejecting the legitimacy of any such statement initiated by American scholars or, alternatively, as a challenge to be self-aware.

I would like to take this postcolonial position for the moment as a positive challenge. This critique reminds us—indeed all of the critiques remind us—that we cannot escape the national and regional influences that have contributed to how we view the world and act in it. We may desire to speak from a universal position, but no such position actually exists. Our ideas and values have been shaped by the languages we speak and read, by the trajectories our lives have traced through particular institutions and countries, and by the intellectual milieux in the places we have lived. Even if we manage to transcend these geographical forces shaping identity, other people will often hear our words in relation to our nationalities. Since we speak in order to be heard and understood, we are not free to ignore this perception on the part of our listeners.

But there are deeper limitations to all of these criticisms. With regard to the comfort women issue, the Japanese right continues, on the one hand, to be highly selective in its use of evidence, and on the other hand to treat any criticism of wartime Japan as a personal insult. In various forms, nationalism forms a part of history education everywhere in the world. The agenda of right-wing groups like Japan’s Society for the Creation of New History Textbooks (Atarashii Rekishi Kyōkasho o Tsukuru Kai) to foster national pride through education is thus hardly exceptional. Yet a defensive nationalist bias that privileges the state and seeks to minimize the suffering of its victims has no place in either the historical profession or the classroom.

The centrist objection may be less overtly nationalistic but assumes the identity of national citizens with their states. People can choose to be defined by other identities too. Many feminists, to take an obvious example, treat the identity of “woman” as more important to forming political solidarities and critiques than the nation. The signers of the Open Letter sought to speak as transnational scholars with a common commitment to the study of Japan and East Asia. It is fair enough to point out that the country where many of us reside has blood on its hands too, but as an objection to our statement it implies that one can only speak as the representative of a nation-state. This limits scholarly speech in a way that is not consonant with scholarly practice. Nor does it grasp the multiplicity of race, class, gender, religious, and other identities.

The postcolonial critique presents the question: can anyone speak at all? Do only victims have the right to speak? After all, it first rejects the conception of a natural identity between nation and state that centrists adopt but then says that as a member of the academy in the dominant country your position is defined by complicity in the hegemony of that country even if you challenge it. This leaves no place for the Western scholar of Japan to stand except as a critic of the enterprise of Japanese studies itself. As important as self-criticism is, it would be strangely navel-gazing and counter-productive to make it our exclusive concern.

One could choose to be silent. The ethical issues for a historian entering political debate are always complex, and the contradictions in this instance may have been particularly acute. Some people would even say that historians should avoid engaging in politics altogether. Yet in less explicit ways, we act politically in what we choose to study and how we approach it, as well as in the ways we teach and write history. Our writing is not intended only for a single national audience, and our classrooms do not accept or exclude students according to their nationality. For these reasons, although political speech involves a different rhetorical style, and the burden of being self-aware is particularly great in an international context, speaking in the political arena, either at home or abroad, is not fundamentally distinct in ethical terms from scholarly writing or speaking in the classroom.

As moral human beings, we should always be able to stand on the side of the victims of injustice. The evidence for Japanese state involvement in the comfort station system is sufficient that it is common sense to demand that the Japanese state should accept responsibility for the women’s suffering. How grave an offense one assesses the system to have been in the larger context of twentieth-century history, however, ultimately depends not just on one’s reading of the surviving evidence and testimony but on one’s view of the entire context of the Japanese wartime state and military. If you believe, as many Japanese conservatives do, that Japan at the time was engaged in a necessary war of national defense, then it will be easier to accept the view that the comfort station system was simply an unfortunate by-product of war, and that reports of abduction and rape by the Japanese military are either false or rare aberrations. If, however, you view Japan’s wartime state and society as themselves distorted and dangerous, then it becomes easier to view the surviving evidence of the comfort women as likely to be just the tip of an iceberg and the comfort station system as a whole as belonging in continuity with mass forced labor, killing of POWs, massacres, vivisections, and other acts of inhumanity.

Similarly, since many Japanese conservatives believe wartime Japan was not abnormal, and in their view a “normal country” (with the United States often providing the implicit model) is one for which citizens are prepared to give their lives, it becomes natural from this perspective to treat all Japanese deaths in the Asia-Pacific War as noble sacrifices. In this context, the wartime slogan “suppress the individual, serve the state” (messhi hōkō) becomes simply an expression of national duty, rather than of an ultranationalism that abrogated private rights and ultimately led to forced mass suicides.

The reading of wartime Japan as a nation drawn into war by forces beyond its control has become increasingly mainstream within Japanese public discourse in recent years. Indeed, Prime Minister Abe’s seventieth-anniversary commemorative speech on August 14th, despite all of the words of contrition it used, accorded with this view. It skirted entirely the problem of ultranationalism or fascism.

To add the piece missing from this picture, we can turn to no better source than Maruyama Masao’s essay “Theory and Psychology of Ultranationalism,” one of the earliest postwar analyses of wartime Japan. In this essay, first published in March 1946, Maruyama conceived wartime Japan as a society based on the “transfer of oppression,” in which arbitrary exercise of power was transmitted through a vast hierarchical structure determined by proximity to the emperor. The accompanying dogma that the military itself embodied the imperial will produced Japan’s peculiar brand of fascism without a charismatic leader. This conception helps explain how men could believe they were conforming to accepted norms of behavior while committing horrific acts of brutality. Maruyama’s essay remains significant today not simply because the author was one of the great political philosophers of the twentieth century, but because of when he wrote it. In March 1946, the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunals had just begun. The Cold War order was also just beginning to take shape, and Maruyama was not a communist sympathizer. His reading of the Japanese wartime system, written just months after he himself had ended service in the imperial army, thus cannot be called a product of Cold War ideological hegemony over Japanese historical interpretation. It gives the lie to one of the fundamental claims of the post-1990s Japanese right, that the Cold War superpowers imposed a “masochistic history” and “denied Japan its own historical consciousness,” because it demonstrates that a sophisticated critical analysis had been articulated indigenously before Japan had settled in its Cold War geopolitical mold.

Maruyama was a product of his time, with his own limitations, and there has been a long history of critical interpretation of his philosophy since. Significantly, his essay lacked a gender perspective. If he had considered it at the time, he might have analyzed patriarchy as part of the system too and recognized that the ultimate victims of the “transfer of oppression” he described were none other than the comfort women, whose status as female as well as from colonies and territories under Japanese occupation placed them at the very bottom of the emperor-state hierarchy.

Although gender and racial discrimination persist in many forms in Japan as elsewhere, and although the postwar Japanese state, taken into the embrace of the U.S. alliance, avoided a full reckoning of its responsibility toward the victims of occupation and colonial rule, the postwar Japanese public overwhelmingly rejected emperor-state ideology together with all the violence that it had licensed. This was an extraordinary transformation. It seems obvious today, but the numerous scholars from outside Japan who have been mentored by professors in Japan and have enjoyed close working relationships with Japanese colleagues in the past two generations have been able to do so because no scholar in Japan continues to espouse the bizarre former orthodoxy of imperial history (kōkoku shikan) based on literal readings of ancient Shinto mythology. We could almost call the “normal country” narrative of the new Japanese right a testament to the success of postwar scholars in consigning this orthodoxy to the dustbin of history. It is also, of course, a product of willful denial.

***

Our letter was just one statement among many in a tumultuous year of memory politics in East Asia. Within Japan, a string of critical public statements on war responsibility was issued by various groups in the months leading up to Prime Minister Abe’s August 14th address.2 Much was wrong with that address, but there is little question that without public pressure, both domestic and international, it would have been worse. At the beginning of his second administration in 2012, Abe had signaled he would retract the government’s statements of apology on the comfort women issue made twenty years earlier. But in August 2015, he found himself officially reaffirming the apologetic language of the Murayama statement of 1995, albeit in a speech filled with passives and vague allusions that suggested his personal distance from the sentiments he was conveying. Four months later, the year ended with the dramatic announcement that the governments of Japan and South Korea had reached an agreement to resolve the issue “finally and irreversibly.” Like the August speech, this agreement was rife with problems, most conspicuous among them that the surviving victims had not been consulted. It remains to be seen whether its net effect will prove to be positive or negative, but in light of Abe’s public statements two years earlier, it certainly represented a strategy of conciliation contrary to what had been expected.

At the time of writing (April 2016), implementation of the agreement has been stymied by refusal on the part of victims and their advocates in South Korea to accept the terms, and on the part of the Japanese government to make any payment into the promised compensation fund before the comfort woman statue erected by activists in front of the Japanese embassy in Seoul is removed. President Park’s conservative Saenuri Party lost its parliamentary majority on April 13, which may make it more difficult for her (or a successor) to follow through on Korea’s side of the agreement. Meanwhile, LDP politicians, including members of Abe’s administration, have persisted in saying and doing things that conflict with the sentiments Abe expressed in his August address and the December agreement, although they probably have the tacit approval of the Prime Minister himself. The ongoing LDP campaign of denial reached many of us in October 2015, when English translations of two right-wing Japanese books arrived in the offices of most of the signers of the Open Letter (along with many other Japan scholars), together with a cover letter from Diet member Inoguchi Kuniko, who is on the party’s International Information Committee. One of these books whitewashed Japanese colonial rule in Korea; the other presented the comfort women controversy as the product of an international conspiracy against Japan.3

If the bi-national agreement unravels (and it is important to note that it is bi-national, since the Japanese government explicitly rejected the possibility of similar agreements with other countries) it will be further proof that states and national leaders do not control the narrative of the Asia-Pacific War. In fact, the comfort women issue has exemplified this since it first surfaced in international politics in the early 1990s. Although the Korean government is often thought in Japan and elsewhere to be using the issue as a cudgel against Japan, in fact Korean governments have not led the drive to demand restitution to victims. When the campaign to seek compensation from Japan began in 1990, it was spurred in part by the casual response to a question in Korea’s House of Councilors by a government representative who suggested that conducting an inquiry would be pointless.4 The Park administration was compelled to act by a 2013 ruling of the Constitutional Court that declared it unlawful for the government not to demand compensation.

|

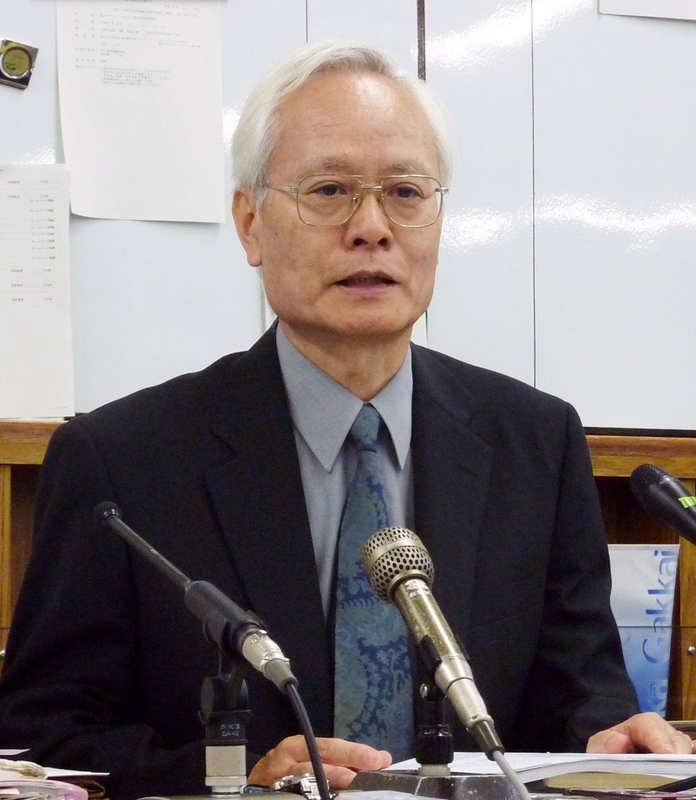

Yoshimi Yoshiaki |

Less than a month after the Park-Abe agreement, verdicts handed down in two libel cases also demonstrated that domestic interpretations of the issue run on separate tracks from international diplomacy. The cases of Yoshimi Yoshiaki in Japan and Park Yu-ha in Korea—authors of the two best-known works of scholarship on the comfort women—also oddly mirrored each other. Japanese historian Yoshimi Yoshiaki’s careful empirical study of the comfort station system was the first work to establish the responsibility of the Japanese military on the basis of documentary evidence. Yoshimi described the system as military sexual slavery. At a public event in 2013, right-wing member of Diet Sakurauchi Fumiki referred to Yoshimi’s work as a “fabrication” (netsuzō). Yoshimi sued for libel. The January 20, 2016 ruling declared that Sakurauchi’s words could be construed to mean no more than that Yoshimi’s writing was “mistaken” or “inappropriate” and that the statement was therefore within the bounds of lawful expression of opinion. The ruling said little about Yoshimi’s book or the comfort station system itself. Addressing as it did the status of the most widely cited empirical study of the comfort women, the verdict thus implicitly conveyed the message that the facts of the issue were unverifiable or unimportant, so that one opinion about them was as good as another. Sakurauchi and the right-wing press read a much broader—and in a sense contrary—message, claiming that the court had established that the system was “not sexual slavery.”5

|

Park Yu-ha |

In South Korea, a guilty verdict was handed down on January 13 in the libel case brought by nine former comfort women, supported by the Korean Council for Women Drafted for Military Sexual Slavery by Japan, against Park Yu-ha, professor at Sejong University and author of Comfort Women of the Empire. This case received more attention from the international press. Yet few outside Japan were able to read Park’s book in full, since an earlier court had required that 34 passages be redacted in the Korean edition, leaving only the Japanese translation complete (the book has not yet been translated to English). Based heavily on excerpts from testimony collected by the Korean Council itself, Comfort Women of the Empire argues that most of the women in Korea were recruited rather than abducted, and that, although they suffered brutal treatment, many of them accepted their roles as fulfilling the duty of imperial subjects. The panel of three judges found that by writing that comfort women had had relationships of comradeship with Japanese soldiers, Park had violated the personal rights of the plaintiffs and gone beyond the bounds of freedom of academic inquiry. In this instance, the case involved an unusually broad interpretation of libel not only with regard to what constituted libelous language but with regard to the parties to the suit, since Park’s book did not refer to any of the plaintiffs by name. The suit thus had the character of a class action on behalf of all Korean comfort women, living and dead, and the verdict implied that collective memory as embodied in the position of the plaintiffs was inviolable, without room for historical interpretation. In contrast to the judges in Yoshimi’s case, the Korean judges analyzed numerous passages in Park’s book, although the verdict made no reference to the author’s evidence. As in the Yoshimi case, at least some activists and media took a broader view of the verdict, treating it as proof that Park was a collaborator and a denier, hence a public menace. Demonstrators demanded that she be removed from her post at Sejong University.6

Although coming on the heels of the state-to-state agreement, these two verdicts bore no direct relation to it. Nor did the state visibly tip the scales in either case. In fact, there was no sign that concern for national reconciliation between Japan and Korea had played a role in either of these domestic cases. For better or worse, civil society in both countries, operating through the courts and the media as well as direct public action, was acting independently of government. The divergence between the judges’ responses in Japan and Korea showed that the issue was anything but “finally and irreversibly” resolved.

From a scholarly perspective, both verdicts are frustrating, revealing how poorly the courts and popular opinion handle the nuanced conceptions of evidence and interpretation that historians hold dear. In the Open Letter, we were trying to speak about the ethics of interpretation, rather than on the plane of “fact” and “fabrication.” Yet these cases highlight the limits of this position in the legal context. At what point should words and interpretations be actionable in court? Which ones? If civil society (including the vast reservoir of hate speech on the internet) is often out of sync with the state, they both speak in registers different from that of academic discourse.

When we gathered in March 2015 to consider issuing a public statement, we discussed the Yoshimi and Park cases, and even considered writing our letter in support of both scholars. Now that a year has passed, the record of our influence in the public sphere appears ambiguous—not deleterious, I hope, but uncertain. If we want to be certain of having some impact as scholars speaking directly to non-scholars, our most important role may still be in the classroom. We closed the letter expressing the hope that our students would inherit a full and just record of the past. Here too, we must be humble. Even as we strive to preserve and pass on an unbiased historical record, our students’ perceptions are formed by more than what we write and teach. We cannot wish away their national attachments. I have had the experience of assigning the manifesto of the revisionist Japanese textbook group and discovering that many American students find it reasonable. The manifesto’s claim that every country should have its own version of history, which should be a source of pride, appears to have accorded in students’ minds with ideas of multiculturalism they had learned to embrace. Many of our students cling to national identities at least implicitly even if they reject overt nationalism. National identities provide security amid the political complexity of a globalizing environment. Confronted with a violent history, many students want to believe that their own country was on the side of justice—or at least that their country was no more evil than anyone else’s country. Even if they are capable of criticizing their present government, it is difficult for many of them to separate state, nation and self when they confront the difficult moral questions around imperialism and war. We can encourage them to question these identities but we can’t expect that anything we do in our teaching will by itself overturn them.

Perhaps the greatest lesson for me in publishing the letter, watching how it was read (particularly in Japan and Korea), and responding to criticisms, was that it made me more conscious of the relation between my scholarly and pedagogical choices and my moral and political beliefs. When you speak publicly on historical memory and when you teach politically difficult issues, you have to be clear in your mind about where you are trying to go: who you want to persuade and what values you wish them to share with you. Your audience will hear moral messages in the historical narratives you offer, regardless of any efforts at detachment or objective distance. Is the message universal pacifism based on claims of complete moral equivalence? Or acceptance of the inevitability of war, based on the same equivalence? Is it “never again” to militarism and fascism, or demonization of a particular belligerent?

Like slavery in the United States, the comfort station system has left a legacy of complex moral questions—about freedom and unfreedom, about national and ethnic-racial identities, about justice and reconciliation, and most important to the practice of our profession, about historical evidence and interpretation. In the course of this past year, I felt repeatedly compelled to question and refine my own moral judgment. Interpreting history and trying to act on one’s interpretations in the present requires continual self-reexamination. If we can impart that much to our students, that in itself might be the most valuable thing we do.

Notes

A related critique from the left asserted that the letter had misrepresented postwar Japan as peaceful toward its neighbors when in fact, as a U.S. ally, Japan was complicit in the violence of American imperialism. Writer Tsuneno Yujiro expressed this position forcefully in a response to the letter in the Asia-Pacific Journal. Tsuneno also questioned the letter’s citing Korean and Chinese nationalism alongside the revisionism of the Japanese right as impediments to resolution. These criticisms speak to the difficult compromises we made in order to include a wide range of scholars and persuade a wide public. Speaking for myself, however, there may also be a substantive difference of political views. As compromised as they have been, I believe that postwar Japan’s pacifism and domestic police restraint are significant achievements when viewed in world historical perspective. With regard to contemporary memory politics, I also believe that nationalism in Korea and China represent impediments as serious as Japanese denial. Acknowledging this political problem in the present in no way equates the three nations in the past or diminishes Japanese responsibility for the country’s history of aggression.

Significant statements included the so-called “16 Organizations Statement” on the comfort women issue published collectively by major historical and pedagogical groups on May 25; the statement on Japanese-Korean relations issued by Japanese intellectuals on June 8; and the statement issued by international relations scholars on July 17 concerning the upcoming seventieth-anniversary address of the Prime Minister. The English translation of the Prime Minister’s address is here.

Inoguchi’s mailing and its context are discussed in David McNeill, “Nippon Kaigi and the Radical Conservative Project to Take Back Japan” Asia-Pacific Journal, December 14, 2015. The contents of the package are analyzed in detail by Yamaguchi Tomomi in “Inoguchi Kuniko giin kara ikinari hon ga okurarete kita: ‘rekishisen’ to jimintō no ‘taigai hatsugen'” Synodos, October 21, 2015.

Sakurauchi was challenging the label “sexual slavery” when he referred to Yoshimi’s work as a “fabrication” but it is important to note that neither the validity of the label nor Yoshimi’s use of it was adjudicated in the ruling. The case was further muddied by the fact that Sakurauchi’s comment was made at the Foreign Correspondents’ Club in response to a statement in English. The judge’s conclusion that it was not libelous relied partly on the fact that the interpreter at the event had mistranslated the word netsuzō as “incorrect” rather than “fabricated.” The full text of the verdict can be found in pdf form through the website of Yoshimi’s support group here.

This was a civil case. Criminal charges were also brought against Park. The criminal case is ongoing at the time of writing.

.jpg)