Introduction

Cultural identity, Stuart Hall reminds us, is not fixed; it is ‘always in process, and always constituted within, not outside, representation’ (Hall 1990: 222). This paper highlights some of the issues associated with the fluidity of identity, and the processes involved in constituting cultural identity within specific types of representation. It uses as a central platform the case of a third generation Japanese/Okinawan boy born in Hawai`i diagnosed with encephalitis, who was healed contentiously by modern US medical science, Okinawan shamanism, or charismatic Christianity, depending on the perspective of the observer. The father’s response to his own identity crisis triggered by his son’s illness and recovery provides an interesting example of how individual agency can lead to the transformation of cultural identity within a highly specific representative context.

This article uses interviews as a basis – and one interview in particular – conducted with a high-profile, highly accomplished Hawai’ian-born second generation Japanese/Okinawan musician, teacher and community leader, Grant (Sandaa)1 Murata, the father of the boy, recorded in Honolulu in November and December 2004.2 In the decade or so that has passed since these interviews were recorded, Grant has cemented his reputation as a senior, committed community leader of Okinawans in Hawai’i. Although the story he narrates about his son below is important, the focus of this essay is on the impact of the events described in the story on Grant’s own identity construction. Demographically a member of both the Hawai`i an-born Asian/American majority and the Okinawan minority3, his identity in contemporary Hawai’i is contingent on his choice of ethnic and cultural orientation. And since the events described below, he has identified primarily with his Uchinaanchu (Okinawan) heritage.4 Grant’s story reveals a number of themes about the processes involved in identity formation, and transformation, located in this case within contemporary Hawai’i.

Hall’s suggestion that identity can only be constituted within representation is a useful starting point from which to think through the messages in the story below. Indeed how Grant made the transition from Japanese American/Asian American to Uchinaanchu revolves around this premise. Until he was able to identify as Uchinaanchu he was unable to resolve many aspects of his life. His son’s illness and his ‘miraculous’ recovery were the catalysts that enabled Grant to make the discursive transition to becoming Uchinaanchu, and to develop his subsequent position on both the role of Okinawan culture in healing his son, and his views on Hawai’i an-born Okinawans’ lives and identities. This consciousness occurred within his representation of himself as first Japanese American, and then as Uchinaanchu in Hawai’i.

Grant’s Miracle Story

Grant’s son was diagnosed with severe encephalitis when he was seven years old in 2001. After three months in a Honolulu public hospital the medical team’s prognosis was that due to the severity of the condition he would make only a partial recovery, and would experience only limited independence after rehabilitation. In effect he would be a highly dependent invalid, unable to walk or to talk, and the parents would need to buy a special wheelchair and bed. There was a good chance that he would be able to communicate however, possibly through writing even if he was unable to speak. Grant’s wife, a sansei5 Hawai’ian born Okinawan, mobilized her spiritual supporters, members of a charismatic Christian church group to which she belonged, to conduct daily bedside vigils beside the boy. There they prayed, sang hymns and talked to him, even though he was unable to respond. Grant was cynical about the value of these meetings at the boy’s bedside. ‘You know, I said to my wife, ‘You people6 have a saying about selling your soul to the devil. Well, I’d do that if that’s what it took to save my boy.’7

That day he phoned his sanshin teacher in Okinawa, Terukina sensei.8

I said, ‘The doctor gave us a really down to earth analysis of this boy. Either we’re going to lose him, or he’s not going to get much better, and we just have to live with it.’ He said, ‘Do you know how he contracted it?’ And I said that we didn’t have any idea. He said, ‘Are wa, byouki de wa nai yo.’ [That’s not an illness]. I said, ‘What the hell you mean – byouki de wa nai yo?’ You’re looking at a kid like this. Nothing is registering. He has to be fed by a tube. At the beginning when we talked to him, he could look at us, so we knew he was aware, but after the second month, there was no response. He was in a coma at that time. I didn’t voice it, but I thought to myself, ‘What the hell does he know about this kind of shit?’ You know.

When his son was hospitalized Grant had yet to discover his own Uchinaanchu heritage,9 yet he had reflexively contacted Terukina sensei to talk about his son’s illness, rather than his own parents, because he was ‘like a father’ to him. In response to the phone call, Terukina told him that coincidentally he was coming to Hawai`i in March to perform, and that he should stand firm with the boy, and continue to give him all his love. ‘The ancestors will not let him die,’ he told him.

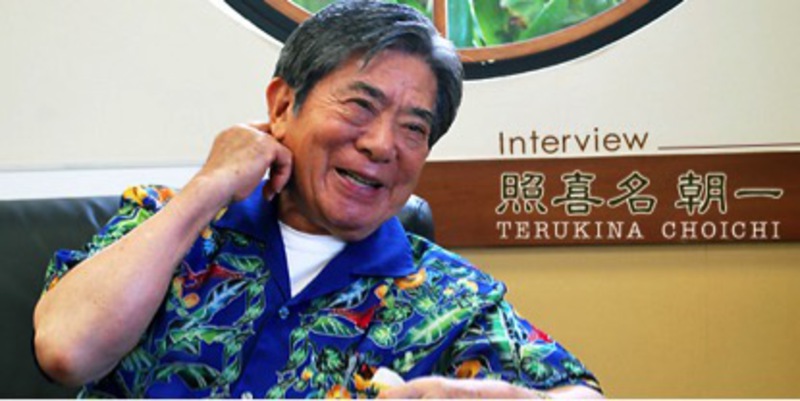

|

Ryukyu Koten Afuso-ryu Ongaku Kenkyu Choichi Kai’s ‘Living Treasure,’ Terukina Choichi, Sandaa’s teacher written up in the Honolulu Festival website in 2010. |

From this point in the story, I would like to let Grant narrate the turn of events in his own words:

When sensei came I expected the worst. Friday he calls me and says, ‘My wife and I, and my son, and my wife’s older sister10 would like to go to the hospital.’ So I piled six of us into my Lexus sedan and went to the hospital.

I still remember real well. We had the last room in the corridor. Sensei, the wife, the sister, and I all walked into the hospital room. But the older sister sat outside the door. She wouldn’t come into the room.

Terukina’s wife came into the room, and she looked at the boy, and talked to him. The boy sort of looked at her and at them. And then she kind of under her breath, she said, ‘Kore daijobu’ [this is fine]. And she left the room. After she left the room, she went to talk to her sister. And then her sister came in the room.

And then she said [in Okinawan], ‘Sanda (Grant’s Okinawan nickname). Can I touch his body, his head?’ ‘Dozo,’ I said. So she started to the boy, she touched his head and his body. When her hands came to his lower back, she stopped and said, ‘Something’s in his stomach.’ ‘Oh yeah,’ I said. ‘He has a feeding tube.’ ‘Ah, Here it’s cold.’ She touched him and said, ‘This child’s fine. He’s ok. And then she says, ‘This bed shouldn’t be in this position. Can we set it up like this?’

Terukina’s sister was a yuta. While yuta occupy an ambiguous and somewhat anachronistic position in Okinawa, practitioners can have significant, often positive impacts on patient health. Using Okinawan signifiers, and genealogy in particular yuta are able to read what they see as ancestral problems, problems with environment, spirituality, or infestation from sources that are beyond the ken of most people, and often employ geomancy, counseling and spiritual solutions to enable their clients to solve their issues.11

Next day was performance day. We had 24 hour round the clock surveillance on the kid. About 2:30, which was exactly the same time of day we were at the hospital the previous day, I got a page on my pager from this frantic old lady, one of the aunties who was watching the boy. I called her and she couldn’t speak – she seemed to be shocked… Goddamn, I thought, he’d died. ‘Speak,’ I said. ‘Oh my god, did he go?’ ‘He’s talking!’ she said.

Now you gotta understand. We didn’t hear this kid talking for two months already. We were told that if anything, speech was going to return to him the last. It was like a dream come true for us at this point, from what the doctors were telling us. She said that she was doing something, and she turned her back, and the boy said to her, ‘Auntie, I’m thirsty. Can I have some water?’

Then I finished the performance and went to the hospital, and he was trying to walk! The next morning, he was holding on to the side of the bed and he would walk. Then he told me that he wanted to eat something: ‘I want to put something in my mouth,’ he said. ‘I don’t want to eat with this stuff.’

Perhaps, as significantly, Ms Terukina took Grant aside to tell him that he needed to do some genealogical research into his own background:

Terukina’s sister told me ‘you need to find the person who give birth to you. Whether it be just to say ‘hi,’ and go to the hakka and make aisatsu, you’ve got to find her.’ [Visit your mother’s grave and present yourself appropriately]. And then Terukina’s wife said to me, ‘I told you some years ago, who are you? First of all you need to start from this point in order to move on.’

So, finally there’s a reason for me to do so. So I looked for my grandmother, and I found her. And then I found the ancestral home. There are still some more things that I need to take care of as far as where to go aisatsu. Though my mother’s Okinawan, my father’s naichi.12 I was told that I need to also find my natural father’s side. Even though they’re Yamatonchu [Japanese] I have to go to aisatsu…13

Following this episode, Grant and his wife divorced over the personal and belief issues that had become more pronounced during the boy’s hospitalisation (his wife retained custody of the boy).

The events in the story narrated above led Grant to ask himself questions about his background, and his own identity. Raised as Japanese-American in Hawai`i by third generation Japanese-American adoptive parents, he had remained unaware of his own Okinawan heritage until this incident. His son’s illness provided the catalyst for him to begin the process of investigating his cultural heritage, and even though he had had many reasons to question it in the past, he had resisted doing so. For example, as a 13 year old he felt compelled to play sanshin, and to do Okinawan dance, even though his parents were not interested. And a few years before his son became ill, Terukina’s wife had asked him ‘Do you never ask yourself the question, ‘who am I’? Who are you?’ He realized that she was asking him to find his roots because she had a powerful sense that he was culturally Uchinaanchu. He resisted the urge to do so, though, because he felt that as his adoptive parents loved him and raised him with warmth and affection, it was somehow inappropriate to ‘spy’ on his birth parents. Moreover, as he says: ‘I really didn’t have an aching to find them, to establish any kind of relationship with them.’14

…

In assessing why who healed this particular boy is significant – or whether indeed it is significant – we need to unpack the cultural history of the boy’s parents, and in particular his father, the background of the Okinawan diaspora to Hawai`i, and the engagement of Okinawans in Hawaii’s ‘multicultural paradise.’

‘Fixing’ identity

Grant’s ethnic heritage is significant. Born in Hawai`i to a second generation expatriate Okinawan mother, and a second generation expatriate Japanese father, Grant was adopted by a third generation Japanese American couple in 1963, and raised as a Japanese-American in Honolulu. He did not know his birth mother or his biological father, and had little interest in them, even though his adoptive parents had told him he was adopted as a baby. He emphasises the ‘American-ness’ of his upbringing when asked to describe his childhood. He says that he was unaware of his Okinawan ethnic and cultural heritage until after the event he described above; that is, after he was already an established performer of sanshin15, a speaker of Uchinaaguchi,16 and an accomplished concert performer, specialising in Okinawan classical music. His denial of his ethnic roots until the events described above is evident in his story, and indeed makes even more dramatic the transformation that followed the ephiphany described in his tale.

|

Sensei Grant (Sandaa) Murata with a sanshin student |

Since his revelation about his cultural identity Grant has held strong views on what constitutes Okinawan identity in Hawai’i, and is critical of ‘ethnic contingency’: ‘Okinawans are like any other ethnic group outside Japan. We’ve come to a point in young people’s lives where being too American has gotten in the way.’17 To Grant, young people of Okinawan heritage born and brought up in Hawai’i, while not unconscious of their shared roots, history, heritage and culture, have chosen to prioritise ‘American-ness’ or ‘Japanese-American-ness’ as their primary form of identification. However when it is expedient or appropriate, many Hawai’ian born Okinawans choose to represent themselves as Uchinaanchu at events such as the annual Okinawa Festival at Waikiki, the annual Okinawan village and town club picnics,18 the sports and activities days organised by the Hawai`i United Okinawa Association (HUOA), and the public performances of Uchinaanchu culture at multiple venues around Hawai`i. As Grant has come to see it, these people do not have a single identity; rather they are always in motion between identities. And in this mobility he suggests they lack commitment.

The idea that identity is not ‘fixed’ is in fact central to this paper. Stuart Hall on the processes of ‘producing’ an identity, expanding on the opening quote stated, ‘Perhaps instead of thinking of identity as an already accomplished fact…we should think, instead, of identity as a ‘production,’ which is never complete, always in process, and always constituted within, not outside, representation.’ (Hall 1990: 222). While Hall focuses on diasporic identities in postcolonial societies, the processes involved in the ‘production’ of identity are also significant in this story of identity transformation. In Grant’s case, his identity transformation from Japanese American to Uchinaanchu, and within the Uchinaanchu group becoming a cultural leader, political activist, and outspoken spokesperson for the group in the wider Hawai`i context, is noteworthy in terms of the production of identity within different forms of representation. It is hard to avoid coming to the conclusion that for Grant identity is indeed a production, constituted within two discrete forms of representation, and it is signposted with significant events.

Grant’s views on what constitutes Okinawan identity do not always cohere with views of the Hawai’ian-born Okinawan community. The Uchinaanchu community in Hawai`i is centered around the Hawai’i United Okinawan Association in Waipahu, about 20 km from Honolulu. The HUOA was formed in 1951, bringing together the numerous town, village and hamlet associations under it as an umbrella organisation.19 In the postwar environment the individual associations decided to form the bridging organisation to revitalise the place of Okinawans in Hawai’i, and today boasts a membership of 49 clubs with over 40,000 people, made up of those of Okinawan heritage and their families living in the Hawai`ian Islands.20 While focussed mostly on social, cultural and sporting activities, the HUOA is also active in promoting relations with Okinawan businesses, and linking Uchinaanchu-owned businesses in Hawai`i with Okinawan businesses. It has an active genealogical society, promotes cultural exchange with Okinawa, and sends students to the homeland every year on scholarships, including those sent to Okinawa International University.

|

The Hawaii Okinawa Center, which opened in 1990, houses a multipurpose auditorium/theatre/banquet facility, named the Teruya Pavillion, that can host up to 1200 visitors. |

Its orientation to Okinawan culture is committed but some younger members have been critical of this commitment; it has been said that many of the activities that are supported by the HUOA could be seen almost as parodies of Okinawan culture.21 While such a view is extreme, it is reasonable to suggest that the organisation has embraced what it sees as ‘Hawai`ian values’ as well as ‘Uchinaanchu values’ as central to its mission.22 The vast majority of association members speak only English – very few members speak either Okinawan [Uchinaaguchi] or Japanese fluently, but their English conversation is peppered with Hawai’ian, Okinawan and Japanese words – and activities that members participate in include baseball, volleyball, picnics, club dinners, and the annual Okinawa Parade and Festival, all of which fit within mainstream US/Hawai’ian cultural norms. The meetings, picnics, and dinners of course always include Okinawan cultural elements, such as the formal greetings, many of the dishes, and the performance of the kachashi – the Okinawan ‘free’ dance in which all participate. There is often also entertainment, which invariably runs along Okinawan cultural lines and includes local Okinawan musical groups and dance troupes, and sometimes musicians and dancers from Okinawa.

Grant, following his teachers’ instructions, believes in traditional methodologies – the ‘old ways’ – of teaching and performing sanshin and Okinawan classical music and dance through the sempai-kohai23 relationship. He believes that this can lead to near ‘perfection.’ Moreover he holds that Okinawans should speak Uchinaaguchi and Japanese, as he does in his everyday life, in his contacts with Okinawan mentors, performers and friends, and in his conversations with Japanese. This differs markedly from how many in the Okinawan community association want to see their culture practised and performed, though they apparently enjoy watching the public performances. In fact there are many Okinawan-Hawai’ians who would like to learn to play sanshin and learn Okinawan dance for fun, for entertainment, or because they want something they can relate to culturally and enjoy one night a week, according to an organiser for the HUOA.24 Such attitudes do not sit well with Grant, a late convert to ‘Uchinaanchu-ness,’ who believes fervently that traditions exist to reinforce identity, and to encourage excellence. Frivolous reasons for playing (or playing with) one’s cultural heritage are not really acceptable.

As he states, ‘Just because anyone participates in Okinawan culture doesn’t make them Uchinaanchu.’ Being Uchinaanchu, to Grant, is a total commitment. It is a fixed place in space-time. He is impatient toward ambivalence, ‘part-timers, amateurs, or pretenders.’ In a similar vein, he states, ‘So there’s a new breed of young Okinawan who thinks that beating their chests and proclaiming, ‘Hey, I’m Okinawan!’ it’s enough. It’s not enough to have Okinawan blood in your veins: you have to have more than this. You need to be committed to your life and to your culture.’25

|

The Higa building hosts the administrative centre and museum/document library and is located next to the Teruya Pavillion. (Photos courtesy of the HUOA website) |

The ‘new breed’s’ approach to engaging identity is mobile and ambivalent, and Grant believes that formulating one’s identity in this way is problematic for the future of the Okinawan community in Hawai`i. He argues that because people are not committed to their culture in the way that Grant is, their engagement with their own cultural heritage swings from identifying as ‘local’ in the way that it is used by Okamura below, to Japanese and through to identifying as Uchinaanchu, depending on the nature of the event/celebration/meeting. This lack of commitment to culture (as Grant sees it) is not about hybridity, which is of course certainly one way of reading the multiple attachments that most people form, but is about disinterest in one’s heritage. He wants those who claim to be Uchinaanchu to be informed about Okinawa’s history and the history of Okinawan migration to Hawai’i, to be culturally educated in Okinawan traditions, to have some linguistic ability in Uchinaaguchi and Japanese language, and to understand their own genealogy. And while he is aware that this is idealistic, he still adheres to the principle of that position. From his perspective some people’s identities are too fluid.

However, as members of the HUOA point out, they are living in Hawai’i, not Okinawa, and their lives are pretty good these days.26 And while of course they focus on living as Hawai`ian citizens they are mindful of their genealogies. How could they not be, when so many of them have been through dramatic social and cultural transitions in Hawai`i over the past 70 years?27 The interviewees emphasized that each had different levels of knowledge about Okinawan history, culture, language, family etc. But they were all informed to a greater rather than a lesser extent about such matters.

Locating Okinawans within Hawai`i’s ‘multiracial paradise’

Cultural identities come from somewhere, have histories. But, like everything which is historical, they undergo constant transformation. (Hall 1990:225).

In order to gain understanding of the context in which Grant engaged and reconstructed his cultural identity it is important to briefly visit the historical legacies of migration to Hawai’i. There have been a number of well recorded migrations by specific groups to Hawai`i. The most significant have been Japanese (including Okinawans), Chinese, Filipino, and Korean, who were all brought to Hawai’i as cheap labour recruited to work in the sugar cane and pineapple plantations in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.28 In particular Japanese, Chinese and Filipino have been dominant influences in the production of discourses of specific cultural identity within the Hawai’ian Islands since the nineteenth century. Over the years since the Second World War, Okinawans, who could be seen stastically as a sub-category of ‘Japanese,’ have reconstituted themselves in the Hawai’ian context as ‘Uchinaanchu’ and some academics have added the ‘diaspora’ label to their historical experience.29

Diaspora today has a number of contemporary meanings,30 including the understanding that resettlement in the homeland is desirable, that there is a longing for the past, a sense of nostalgia, a sense of community in the newly settled land, and a sense of a future trajectory which involves the retention of at least some elements of a past culture, language, religion and identity. Ien Ang has modified this, saying:

Overall, the term is reserved to describe collectivities who feel not fully accepted by, and partly alienated from, the dominant culture of the ‘host society’ where they do not feel (fully) at home. In other words, where the classic definition of diaspora emphasised the traumatic past of the dispersed group, in today’s usage trauma is located as much in the present, in the contemporary experiences of marginalisation or discrimination in the nation-state of residence (Ang 2007: 285).31

Assuming that the power relations Ang has identified are transferable, in the case of Okinawans in Hawai’i, the alienation from the dominant culture or the ‘host society’ is somewhat cloudy (and the desire to return home permanently is largely absent). This is because, apart from the indigenous population, everyone is foreign.32 Who, exactly, constitutes the majority or the ‘host society’ in Hawai`i today is debatable.

John Okamura has written about precisely this topic in his book, Ethnicity and Inequality in Hawai’i. It is clear that self-identified Japanese-Americans, who currently make up close to one quarter of the total population of Hawai`i,33 are not diasporic in the context of Ang’s interpretation of what a diaspora is above. Indeed, numerically, they are the largest part of the largest ethnic grouping in the islands (Asians constitute 38%, haole 26%, and people who identify as being of two races or more 23%), according to the 2012 Census.34 They do not appear to suffer discrimination in Hawai’i today, though historically they certainly have.35 And while there is a clear perception that as a group they share a certain cultural background and ethnicity, collectively they do not appear to experience much trauma in contemporary society, though this was not always so. This perception of their socio-cultural location within the mainstream also applies to Okinawans, who statistically are seen as a sub-group of Japanese in Hawai’i, though as we see below, from ‘inside’ the group there is considerable dissonance about such labelling.

Unsurprisingly, the demographic statistics do not really tell the whole story; many Hawai’ians identify with multiple ethnic backgrounds, and in some cases can choose which ethnicity to claim, depending on familial and personal circumstances, as we saw above. Moreoever, in official surveys – including the Census – it is common for respondents to claim membership of multiple ethnic groups.36 Regardless of which ethnicity one claims, the Hawai`i United Okinawa Association believe that there are currently about 60,000 people (most of mixed ethnicity) who are Uchinaanchu.37 If this group was to stand alone in the demographic statistics, Hawai`ians of Okinawan ancestry could make up about five percent of the population on the basis of these numbers.

In practice, though, to Hawai`ian-born Okinawans being Uchinaanchu means something quite different to their incorporation into the statistical categories of ‘Japanese’ or ‘Asian’ descent. As Hall has argued, formation of a group’s cultural identity is a process that is contingent on the shifting tides of history, and Okinawans’ identities in Hawai’i have shifted with the times (Hall 1990: 225). In the early twenty first century many say that they are simultaneously Okinawan, Japanese, and Hawai`ian.38 This position though is probably primarily that of the second and third generation Okinawans (nisei and sansei), formed after many years of life in Hawai`i. As with other former migrant communities, Okinawans in Hawai’i in the current era occupy a range of socio-economic and political positions. Their history in the islands plays a significant role in determining how people are located today.39

Relations between naichi40 and Uchinaanchu in Hawai’i were often subtly, and sometimes not so subtly, prejudicial towards Okinawans. This did not reflect the circumstances in Japan in the immediate postwar, when there was little evidence of discrimination by Japanese towards Okinawans.41 It can be argued that these relations in Hawai`i were negative due to a number of historical factors. The first of these were the relations between Japanese and Okinawans that were effectively ‘frozen in time’ at the moment the new migrants arrived in Hawai’i (1900-1920). This was a time when mainland Japanese perceived Okinawa as the new, primitive, proto-Japan, colonised in the late nineteenth century.42 Most of the early Okinawan migrants (men and women) worked in the sugar cane plantations, and as new arrivals they were situated within the hierarchy of the plantation workers below those Japanese who had arrived in Hawai`i earlier. In the physical layout of the houses on plantations and in the pay scales awarded to workers the place of Okinawans below Japanese was reinforced.43 It is worth noting that while many Okinawans, Japanese, Chinese, Filippinos and other migrant groups were initially recruited to work in the sugar plantations, many left the industry after the terms of their initial contracts expired. Some returned home, while others stayed on in Hawai`i as private businesspeople, farmers, and labourers. Notwithstanding the integration into the wider community, the work choices of Okinawans in Hawai’i which often reflected their own cultural upbringing – pig and chicken farmers, market vegetable growers, and other agricultural pursuits – influenced how Okinawans as a group were seen by Japanese and others in the islands.

The view held by Japanese that Okinawans were inferior persisted in Hawai’i until the end of World War II. In this view of Okinawans as ‘primitive’, Okinawans in Hawai’i were seen by naichi to be pig and chicken farmers with poor language skills and manners, hirsute and dark skinned, but were still tolerated by naichi in work, education and social engagements, including marriage in some cases.44 World War II was a watershed for Okinawans and Japanese in Hawai’i, and led to significant changes in race relations. The fact that most Japanese and Okinawan farmers on Hawai’i were not incarcerated as they had been on the West Coast of the United States inspired some confidence among Okinawan and Japanese.45 This situation was compounded following the successes of the 100th Infantry Battalion and 442nd Division of Nisei racially segregated troops who performed with distinction in the European theatre in 1943-5.46

Discrimination directed by Japanese towards Okinawans in Hawai’i following the war declined rapidly; after all the concept of Japan as hierarchically superior to Okinawa was meaningless in the wake of Japan’s defeat. However popular perceptions persisted into the 1950s and 60s that Okinawans were unclean pig-raising people, and it was best not to get too close.47 Such animosity, subtle in most cases, contributed to the ongoing sense of shame, which many Okinawan nisei discussed in the 1981 University of Hawai’i Ethnic Studies’ oral history project. This sense of shame, that they somehow were incapable of performing to naichi standards persisted into the third generation.48

By identifying themselves as different from Hawai`ian born Japanese, Uchinaanchu have used the otherness of Japan to reconstruct ideas of who Hawai’ian born Okinawan are. That is, there is an awareness that they are not Hawai’ian born Japanese, but rather have a different cultural consciousness based on how they read their historical experience. Indeed, it is arguable that the community consciousness is so strong largely because of the collective memory of local history on Okinawa: this explains the need many Uchinaanchu felt that they had to defend their honour, their integrity, their livelihoods and their culture, in the face of Japanese (naichi) discrimination on Hawai’i, and in Okinawa.49 And of course the transmission of such stories through the generations reinforces the historical nature of the conflicts that dominated the early relations between Japanese and Okinawans, both in Okinawa and in Hawai`i.

Jonathon Okamura writes,’ethnic identity and ethnic relations are far more problematic and complex than might be assumed from the islands’ reputation as a veritable ‘racial paradise’ and multicultural model for other racially and ethnically divided societies’ (Okamura 2008: 21). He identifies multiple social, demographic and historical processes that have contributed to this situation emerging. It is difficult to argue against Okamura’s position concerning the inadequacy of the ‘multiracial paradise’ moniker that has been plastered on Hawai’i by ill-informed novelists, travel writers, advertisers, journalists, cinematographers and so on. Indeed one of the things that makes Hawai’i interesting from outside is precisely the complexity of the ethnic politics that underscore many social, cultural, political and economic activities in the islands. Although, as Tamura argues, mainland American cultural values have come to dominate Hawai`ian life since statehood in 1959, it is not a wholesale ‘Americanization’.50 In fact, culture and ethnicity are still dominant markers of many aspects of life in Hawai`i, and they provide boundaries, barriers, and rules for many interactions in many spheres. They influence social, political, economic, religious, and cultural relations. And of course, they influence personal relations.

In the context of Hawai’ian born Okinawans’ continued self-reliance, and self-identification, Grant’s own revelations about his Okinawan-ness that followed the life-changing catalyst in the story above offer some interesting insights into factors that contribute to the mobility of identity, as it is experienced. Employing his own agency to enable his transformation from Hawai`ian born Japanese to staunch Uchinaanchu, Grant has actively engaged the (re)production of his own identity. In doing this he has remained loyal to the values he articulated in the interviews conducted in 2004. In fact, his commitment to Okinawan culture, through his music and his advocacy for Okinawan people on Hawai’i has led to both a high profile and increasingly influential position of the group within the island’s multicultural community.51

After the story

So, how does one read Grant’s story? Grant’s agency in choosing to pursue a life that was committed to Uchinaanchu culture followed his belief that the intervention of the Okinawan yuta in his son’s case was successful. He read the intervention as being a vindication of the power of his Okinawan roots – that he had a birth-right, as did his son – and that by invoking traditional healing methods he was able to help save his son’s life. It should be noted here that his wife’s role in this story, while elided in the narration, is potentially highly significant too. That is, as a devout member of a charismatic Christian church in Hawai’i, she and her fellow parishioners would sit by the boy’s bed every day and chant prayers, sing and ask for the Lord’s intervention. Unsurprisingly, as Grant told me, she believed that his recovery was due to her ongoing faith and God’s intervention. Interestingly neither credited contemporary medical practices with healing the boy, both relying on external obviation as the cause for his ‘miraculous’ recovery.52

One impact of the story is that Grant’s epiphany about his cultural identity led to him taking on a more prominent role in the expatriate Okinawan community. With his deep-seated interest in Okinawan music, language and culture, and his intense study of language and music, he was poised to make a life-changing shift, and his boy’s recovery from his illness provided the catalyst for this change. One of his main goals was to follow in the footsteps of one of the most dynamic and influential community leaders in Hawai’i, Albert Miyasato:

It’ll be many years before I’ll be able to fill Albert’s shoes, but I hope that if I surround myself with the right people, and keep contact with the old ways, and with good people, then I’ll be able to do so in a real way. This will enable us to keep the concept of identity pure [author’s italics].’53

|

Grant Murata teaches the Kachashi to Jennifer Waihee, Erin Kobayashi and Ali Kato at the Hui Makaala 2008 Installation Banquet. Courtesy Hui Makaala website. |

His perceptions of ‘pure’ identity appear eclectic as we saw above; ethnically, all are welcome if they can trace Uchinaanchu heritage, but to be ‘true’ Uchinaanchu one has to commit to that identity – through the ‘old ways.’ In this fixed conceptualisation Okinawan identity is at odds with the more mainstream representation of Uchinaanchu identity promoted by the HUOA, which emphasises pride in the local, American and Okinawan cultures simultaneously. There is little or no identification with being ‘Japanese’ among HUOA members, who make the very clear distinction between Japanese and Okinawans in Hawai’i.54 That is, it is intentionally fluid and mobile. In fairness it too is anachronistic in contemporary Okinawan society, which has become increasingly ‘Japanised’ over the past 40 plus years since reversion to Japan.

Grant’s perception of both his newfound identity and of the identity of Uchinaanchu in Hawai`i is bound up with ideas of the ‘traditional’ Okinawa, with systems of hierarchy, language, religion and cultural ideals perceived as essential and immutable. The narrative in which he’s chosen to locate himself, and by extension, those around him is that of adherence to values of an anachronistic culture in the most literal sense; a culture that no longer exists in the form that Grant applies to his own life experience. In embracing the values of the ‘old’ Okinawa within the geographical and socio-cultural context of contemporary Hawai’i, Grant’s anachronistic approach did not sit well with more politically and culturally ‘flexible’ Hawai`ian born Okinawans, such as some members of the HUOA.55 Nevertheless Grant adheres unswervingly to his ideology, which has enjoyed increased support from the wider Okinawan community now, ten years later.

Hall on the relationship between past, present and representations, wrote that ‘far from being grounded in a mere ‘recovery’ of the past, which is waiting to be found, and which, when found, will secure our sense of ourselves into eternity, identities are the names we give to the different ways we are positioned by, and position ourselves within, the narratives of the past’ (Hall 1990: 225). Grant has actually attempted to ‘recover’ his cultural past, which was coincidentally waiting to be found. And when he had recovered his past, he was able to create a sense of trajectory into the indefinite future. Prompting him to recover his history was the life changing event of his son’s recovery from encephalitis which in turn led to producing Grant’s own engagement with the past and ‘recovering’ his own Okinawan identity. He locates himself firmly within the history of Okinawa, with the diaspora to Hawai`i, and within the Hawai’ian born Okinawan community. The narrative of his son’s miraculous recovery adds weight to his commitment to Uchinaanchu life and culture in the Pacific.56 And although the Okinawa with which Grant so closely identifies has been altered irrevocably over the past 40 or 50 years this does not affect how he positions himself within the narratives of the past.

It is clear that the processes involved in producing his Uchinaanchu identity are contingent. The contingencies include his personal adoptive history, and his ‘natural’ cultural and ethnic background; his choice to become a musician specialising in Okinawan music; his love of languages and his mastery of Japanese (at home) and Uchinaaguchi (in Okinawa); his upbringing as a ‘Japanese/American;’ and on his agency. Of course the catalyst for the emergence of his strong pro-Okinawan agency was his son’s ‘cure.’ Following his perception of the efficacy of Okinawan religion, Grant’s search for the ‘authentic’ has continued. He plays authentic Okinawan classical music, and his students play only pieces approved by the Okinawan Sanshin Board. His sanshin playing, his singing of Okinawan classical and modern music, and his teaching and musical direction are regarded in both Okinawa and Hawai’i as outstanding, and his commitment to Okinawan culture and arts in Hawai`i is unwavering. It takes hard work, and commitment to be Uchinaanchu in Hawai’i. As he says:

If we don’t find ways of getting to young guys the movement will die. I’ve been known to defy my elders; people don’t like the idea of being asked “why” all the time, but I can’t blindly follow orders. My sanshin teacher, Chochi Terukina, though, demands that I do this. So now, I tell my students that they must go to Okinawa and spend time there – usually three years or so – until they understand language and culture, and then come back. I think the performing arts community has upheld these principles of what it means to be a teacher and student more that any other sector of the Uchinaanchu community. And I’m proud of this.

Conclusion

Cultural identity is a production. It is a complex phenomenon that hinges around multiple contexts. It is contested, and as this case demonstrates, individual agency can influence individuals’ choices about how to identify, and why they identify with any stated sets of values. While the process of forming a cultural identity is certainly often linked to perceptions of the past, and particularly of the collective past, in the case discussed here the idealised cultural past of Okinawa has become a signifier for Grant. Okinawa’s history is contentious,57 multicultural,58 and multilingual; it is difficult to pigeonhole the history of the islands, just as it is difficult to essentialize the characteristics that make up ‘Okinawans’ either at home or in ‘diasporic’ locations. Yet for Grant, living in Hawai’i, an essential Okinawa is the context that he employs in defining himself and Hawai`ian born Okinawans. In moving from one named cultural group to another, Grant has fixed his cultural identity, and the identity of Okinawans, in space-time, and has moved subjectively to occupy a place in this continuum. In shifting his own cultural identity he has produced a version of what Okinawan identity means to him, and how it should be lived in Hawai`i.

Unable to actually speak for himself (literally), and dependent on the actions of three groups of invested agents – his mother, his father, and the hospital – the boy in this story during his hospital stay remains in a contested space insofar as identity is concerned.59 His mother believes that his recovery was due to Christian prayer and a benign Christian god. His father believes that his recovery was due to the interventions of Okinawan shamans. His doctors believe that a ‘spontaneous remission’ occurred – not unheard of in medical circles.

The narrative also highlights how one person chose his cultural identity, how he used his individual agency in making choices, and what factors influenced these choices. This of course suggests that identity is constructed – a production. In this case, the production of Grant’s cultural identity is an interesting amalgam of lived experience, the local cultural context in which he’s grown up, his own cultural background, his political awareness, and the powerful Okinawan signifiers that surround him in Hawai’i. But missing from the story are the perspectives of the others involved. Neither his first wife’s nor his son’s perspectives are emphasised by Grant in his rendition of the tale, nor indeed is the hospital’s. Nor should they be, because it is Grant’s story. Nevertheless, the absences are palpable. In telling the story of his son’s miraculous recovery, Grant’s emphasis is only partly on his son’s condition. It is just as much about Grant, and his awakening to his Okinawan identity, which had been dormant for more than 30 years. And now, ten years after the event, Grant’s position as an established performer, mentor, and senior figure in the expatriate Okinawan community is unchallenged.

This leaves us with the question of whether who healed the boy is important. From Grant’s perspective, who healed the boy is of the utmost importance. Grant’s assessment that the Okinawan yuta healed his son of a condition that Western medical science could not cure was enough to jump-start his ongoing commitment to Okinawan cultural identity. And once started, his belief in the ‘old ways’, and his energetic engagement with Okinawan culture through his sanshin performances and teaching, as director of Afuso Ryu Ongaku Kenkyu Choichi kai (the Okinawan Music and Dance Ensemble), as a senior figure in the community, and as a public speaker has ensured that there will be an ongoing legacy of Uchinaanchu culture in Hawai’i.

Matthew Allen, The Cairns Institute, James Cook University and an Asia-Pacific Journal Contributing editor. Matt is currently working on projects on war and memory in Okinawa and in Japan. His most recent publications have been on popular culture and Japan (see below), and on war, memory and museums in Australia and Japan. Matthew Allen and Rumi Sakamoto are the editors of Popular Culture and Globalisation in Japan (Routledge 2006) and Japanese Popular Culture, a four volume collection for Routledge’s Critical Concepts in Asian Studies (2014).

Recommended citation: Matthew Allen, “Producing Okinawan Cultural Identity in Hawai’i’s ‘Multicultural Paradise’,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 13, Issue 9, No. 1, March 9, 2015.

Related articles

• Steve Rabson, The Okinawan Diaspora in Japan at War

• Steve Rabson, “Being Okinawan in Japan: The Diaspora Experience”

• Christopher T. Nelson, Dances of Memory, Dances of Oblivion: The Politics of Performance in Contemporary Okinawa

• Nobuko Adachi, Ethnic Identity, Culture, and Race: Japanese and Nikkei at Home and Abroad

References

Allen, M. 2002, Identity and Resistance in Okinawa. Rowman and Littlefield, Lanham, MD.

Ang I. 2007, ‘Beyond Asian Diasporas,’ in, R. S. Parrenas and C. D. S. Lok, (eds), Asian Diasporas: New Formations, New Conceptions. Stanford University Press, Palo Alto, Ca: 285-290.

Arisaki M. 1996, Okinawa gendaishi [Recent History of Okinawa]. Iwanami Shinsho, Tokyo.

Cohen, R. 1997, Global Diasporas. UCL Press Ltd., London.

Ethnic Studies Oral History Program (ed.) 1981, Uchinaanchu: A History of Okinawans in Hawai’i. Ethnic Studies at University of Hawai`i, Manoa, Honolulu.

Hall, S. 1990, ‘Cultural Identity and Diaspora,’ in J. Rutherford (ed.) Identity: Community, Culture and Difference. Lawrence and Wishart, London.

Hawaii Nikkei History Editorial Board (ed.) 1998, Japanese Eyes. American Heart: Personal Reflections of Hawai`i’s World War II Nisei Soldiers. Tendai Educational Foundation, Honolulu.

Hawaii United Okinawa Association The Hawaii United Okinawa Assocation website (available at http://www.huoa.org/nuuzi/about/about.html)

Hokama S. 1996, Okinawa no rekishi to bunka [Okinawa’s History and Culture]. Chuo Koronsha, Tokyo.

Johnson, C. 1999 (ed.), Okinawa: Cold War Island. Japan Policy Research Institute, Cardiff Calif.

Kerr, G. 1960, Okinawa: The History of an Island People. Tuttle.

Nakasone R. 2002, Okinawan Diaspora. University of Hawai’i Press, Honolulu.

Nelson, C. 2008, Dancing With the Dead: Memory, Performance and Everyday Life in Postwar Okinawa. Duke University Press, Durham.

Ohashi H. 1998, Okinawa shaamanizumu no shakaishinrigaku kenkyuu [Social Psychological Research into Okinawan Shamanism]. Kobundou, Tokyo.

Okamura, J. 2008, Ethnicity and Inequality in Hawai’i. Temple University Press, Philadelphia, PA.

Okihiro, G. 1991, Cane Fires: the anti-Japanese movement in Hawai’i 1865-1945, Temple University Press, Philadelphia, PA.

Ota M. 1999, ‘Re-examining the History of the Battle of Okinawa,’ in C. Johnson (ed.) Okinawa: Cold War Island. Japan

Policy Research Institute, Cardiff, CA 13-39

Ota M. 2002, Essays on Okinawa Problems. Yui Publishing, Naha.

Reis, M. 2007, ‘Theorizing Diaspora: Perspectives on ‘Classical’ and ‘Contemporary’ Diaspora.’ International Migration. Vol. 42, no. 2: 41-59.

Safran, W. 1991, ‘Diasporas in Modern Societies: Myths of Homeland and Return’, Diaspora, Vol. 1. No. 1: 83-99.

Tamura E. 1994, Americanization, Acculturation, and Ethnic Identity: The Nisei Generation in Hawaii. University of Illinois Press, Urbana.

Tomiyama I. 2000, ”Spy’: Mobilization and Identity in Wartime Okinawa,’ Japanese Civilisation and the World. XVI Nation-State and Empire. Senri Ethnological Studies no. 51. Osaka: National Museum of Ethnology.

Trask, H.K. 1999, From a Native Daughter: Colonialism and Sovereignty in Hawai’i. University of Hawai`i Press, Honolulu.

United States Government 2014, US Government Census Hawaii Census Data. Available online at: www.census.hawaii.gov (accessed May 4, 2014).

Notes

1 His nickname, Sandaa, means ‘rascal’ or ‘joker’ in Okinawan.

2 Grant Murata, interviews with the author, HI, November 12, November 15, November 24, December 2, December 3, 2004.

3 Statistically Hawai`ians of Asian descent are the single largest group of people identified in the 2012 United States Government Census. Okinawans make up a small percentage of this large group as we see below.

4 Uchinaanchu means ‘Okinawan’ in Okinawan Shuri dialect, and has also been used in Hawai’i by Okinawans to describe themselves.

5 Third generation.

6 Grant is referring to his ex-wife’s religious group here.

7 Grant Murata, interview with the author, Honolulu, December 2, 2004.

8 Mr Terukina was Grant’s biggest supporter when he was learning sanshin (also known as shamisen) from him in Okinawa. At the time Grant was comfortable with his identity as ‘Japanese American’ as we see below. Terukina had recognised Grant’s talent early and had encouraged him to embrace his hidden ‘Okinawan-ness.’

9 There is more discussion of this issue – which is quite central to the article – below.

10 Terukina’s older sister was a yuta, an Okinawan shaman. Yuta are still perceived in Okinawa to have access to the spirit world, and are often brought in to consult in situations where medical or psychiatric systems are unable to provide any relief to those who are arguably afflicted by a spiritual condition. See Ohashi (1998) and Allen (2002) for lengthy discussions on the topic.

11 See in particular Ohashi’s (1998) work on Okinawan shamanism and spirituality and culture in an Okinawan psychiatric context.

12 Naichi is the word often used by Okinawans to describe Japanese from the main islands, as opposed to Okinawans.

13 Grant Murata, interview with the author, Honolulu December 2, 2004.

14 Murata, interview with the author, Honolulu, December 2, 2004.

15 The sanshin is a three stringed lute, often called shamisen by mainland Japanese.

16 Uchinaaguchi is the Okinawan pronunciation of the ‘Okinawan language;’ speakers of Okinawan dialect are speakers of Uchinaaguchi. This comes from the words ‘Uchinaa‘ [Okinawa] and ‘guchi‘ [language]. Grant spent three years in Okinawa as a young man, learning both Uchinaaguchi and Japanese, and is regarded as an outstanding speaker of both. He has continued his study of the language since his return to Hawai`i.

17 Grant Murata, interview with the author, Honolulu, December 2, 2004. He was referring to the Japanese American community on the mainland, which he assessed as having become increasingly mainstream, in the sense that they had become ‘assimilated’ into US society and culture.

18 These club picnics are annual events held by the so-called ‘locality clubs’ formed by immigrants from specific places in Okinawa who settled in Hawai’i. These clubs include many of the small towns and villages that supplied the emigrants who moved to Hawai`i in the early twentieth century, such as Itoman, Haebaru, Gushikawa, and Ishigaki.

19 The town, village and hamlet associations were all established in the early twentieth century as a means of Okinawans from the same district at home maintaining cultural, linguistic and social ties in Hawai’i. They also formed the basis for community based loan lotteries, but since the 1940s were declining in member numbers, hence the decision to form a united front, with a centralised management structure, formalised facilities and numerous committees to handle a range of social and charitable activities.

20 The HUOA claims this number of members in 2014.

21 P.D., Okinawan musician, interview with the author, Honolulu, February, 2004.

22 W.M., former president of the HUOA, interview with the author, Waipahu, Febuary, 2004.

23 The sempai-kohai relationship refers to the hierarchically bounded relationship between two people in a senior-junior, or teacher-student relationship. In the Japanese and Okinawan contexts this relationship is a formal and binding one, and demands the submission of the junior partner to the senior’s dictates.

24 B.M., interview with the author, Waipahu, Hawai’i United Okinawan Association Center, November 14, 2004.

25 Grant Murata, interview with the author, Honolulu, December 2, 2004.

26 This suggests that minority subjectivity is defined through oppression.

27 Three members of the Hawai`i United Okinawa Association, interview with the author, HUOA Centre, December 17, 2007.

28 The White (haole) population formed the basis for Hawai’i’s colonisation and economic and political control in the 19th and 20th centuries. Haunani Kay Trask has written extensively on the disenfranchisement of indigenous Hawai’ians at the expense of the White settlers, who bought up most of Hawai`i’s land, spread Christian ideology, and reformatted society to suit foreign capital’s interests at the expense of Hawai’ian indigenous culture and traditions. See Trask (1999).

29 See Ronald Nakasone’s edited volume, The Okinawan Diaspora, for example.

30 The word’s origins are from the Greek diaspeirein – to disperse, or spread about (Cohen 1997:2). According to Reis (2007: 41-59), the use of the term can be divided into three identifiable historical periods: the classical period (relating to Ancient Greece and the movement of people in the classical world), the modern (which follows the flow of capital and slavery from the 16th century to the end of the Second World War) and the late-modern (from the Postwar period onwards). In much literature the term ‘diaspora’ has been employed to refer to the Jewish experience of living beyond the homeland from the eigth to the sixth centuries BCE. And consistent with its specific ethnic history, it was used in a newer context to describe the postwar resettlement of Jews since 1945 (Cohen 1997).

31 I think there are conceptual problems associated with the broad-ranging meanings applied by Ang in the above context; one element of ‘diaspora’ even in the more modern context is that of ethnic or cultural affinities that exist within the ‘diasporic’ community. In other words, it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that Ang is more concerned with subalternity, and spontaneous groupings of people in contradistinction to the mainstream, than with border crossings and integration, or otherwise, within host societies. And it is hard to justify the equivalence of the terms ‘diaspora’ and ‘subalternity.’

32 In the 2012 US Government Census, approximately 10 percent of people living in Hawai`i identified as being of either Hawai`ian or Pacific Island descent. See the US Census website for up to date information on these data. Accessed May 2014).

33 Figures cited in this paragraph are from the US Government Census, 2012. See above.

34 Haole is the term used by Hawai’ians to describe ‘white people,’ and appears to be relatively value free these days. It has been widely adopted in the Hawai’ian English language lexicon, and is usually used to refer to White Americans.

35 Japanese were initially recruited to work in the sugar cane fields, working in low paying, difficult, and arduous jobs, often as indentured labour under severe duress. Racial discrimination was legion throughout the islands, and the superiority of the haole was undisputed publicly.

36 Between 2003 and 2005 I conducted about 40 interviews with Hawai`i born Okinawans. The informants identified as ‘Okinawan-Hawai’ian,’ ‘Okinawan-American,’ ‘Japanese American,’ and ‘Hawai`ian’, depending on the individual and the type of questions being asked. For example, concerning education and commerce, most said that they were simply members of the Hawai`ian community. But concerning their ancestry or their social commitments, many foregrounded their Okinawan-ness.

37 W.M., former president of HUOA, interview with the author, HUOA Center, Waipahu, December, 2004. This number includes those who are not members of the HUOA.

38 B. M., J.A., interviews with the author, Waipahu, December, 2003.

39 Arakaki Makoto, ‘Hawai’i Uchinanchu and Okinawa: Uchinanchu Spirit and the Formation of a Transnational Identity’ in R. Nakasone (ed) Okinawan Diaspora, Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2002.

40 Naichi is one word in Uchinaaguchi that describes ‘mainland Japanese.’

41 That is, apart from the wholesale betrayal of the Okinawan people by the Japanese government in the peace settlement that led to the occupation and governance of the former prefecture by the United States (Kerr, 1960).

42 Iha Fuyuu, the ‘father’ of ‘Okinawaology’ who wrote the Ko Ryūkyū (Ancient Ryukyu), proposed the widely accepted theory in nineteenth century Japan that Okinawans were descended from the same cultural and linguistic proto-cultures as Japanese, but were effectively less-developed than their more ‘civilized’ cousins. The language in particular was able to demonstrate how Japanese had evolved more than Okinawan from a similar linguistic base.

43 See Ethnic Studies Oral History Program (ed) (1981), for an in-depth account of Okinawan individuals’ stories of life in the sugar cane plantations, and the powerful ethnically bounded hierarchies that were enforced.

44 See for example, Henry Toyama and Kiyoshi Ikeda’s account, ‘The Okinawan-Naichi Relationship’ in Ethnic Studies Oral History Program (ed) (1981: 127-142).

45 See Gary Okihiro’s Cane Fires: the anti-Japanese movement in Hawai’i 1865-1945, for a comprehensive examination of discrimination directed at Japanese in Hawai`i until the end of the war years.

46 Of the many publications available on the exploits of the nisei soldiers during World War II, probably the most evocative and detailed account is Hawaii Nikkei History Editorial Board (ed) (1998)

47 Interview with J.A., Waipahu, December 2004.

48 C.M., sansei student, interview with the author, Honolulu, December 2004. Carole was at pains to discuss how the idea of comparative shame influenced her own decision not to marry a Japanese Nisei boy.

49 Discrimination against Okinawans by Japanese has been well researched, particularly in the homeland. See Allen (2002); Arisaki (1996); Hokama (1996); Johnson (ed.) (1999); Ota (1999, 2002); and Tomiyama (2000). In the Hawai’ian islands, stories of discrimination experienced by Okinawans at the hands of Japanese in particular are available in Nakasone (2002) and the Ethnic Studies Oral History Project (1981) for example.

50 See in particular Eileen Tamura’s acclaimed book (1994), for an account of how the second generation of Hawai’ian born Japanese have embraced many ‘American values’ in redefining their own cultural identity.

51 See Okamura, above.

52 As an outsider with no access to the medical records, the author is unable to make any claims to medical or other interventions’ effectiveness.

53 Murata, interview with the author, Honolulu, December 3, 2004.

54 W.M., former president of HUOA. W.M. emphasised that pride in Okinawan achievements in Hawai`i are invariably juxtaposed with what is perceived as the ‘lack lustre’ approach to Japanese culture in Hawai’i, which led to the near bankruptcy of the Hawai`ian Japanese Centre in 2000. W.M. explained in great detail how the HUOA was able to help out the Japanese Centre through donations, and through passing on expertise in managing an organisation.

55 Four HUOA members, interview with the author, Waipahu, HUOA Centre, November 15, 2004. They discussed Grant’s ‘kinda narrow’ approach to Uchinaanchu culture in Hawai`i and questioned whether he could be a ‘little more laid-back’ in his attitude.

56 Murata’s story is well-known within the Hawai’ian born Okinawan community.

57 See Ota (1999), for example.

58 See Allen (2002) and Nelson (2008) for examples of multicultural Okinawa.

59 The reader will note that the boy’s name is not mentioned in the text.