The Chinese and South Korean governments have recently announced the building of a new monument to An Jung-Geun in Harbin. An is most famous for his 1909 assassination of Itō Hirobumi, a high Japanese official who framed the Meiji constitution, served as prime minister, and is credited with being one of the great modernizers of the Meiji period. Itō also led Japan’s colonization of Korea and negotiated the Treaty of Shimonoseki with Li Hongzhang, which concluded the Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895), giving Japan control over Taiwan, the Kwantung Peninsula, and reparations equal to several times the Qing Empire’s annual budget. For these reasons, Itō is widely reviled and An lionized in Korea and China. By contrast, Itō remains an iconic figure in Japan and the Japanese government has responded to the news of the plan to honor the man who killed one of the nation’s modern heroes in this way by stating that it would “not be good for their relations and that An was a criminal.”

|

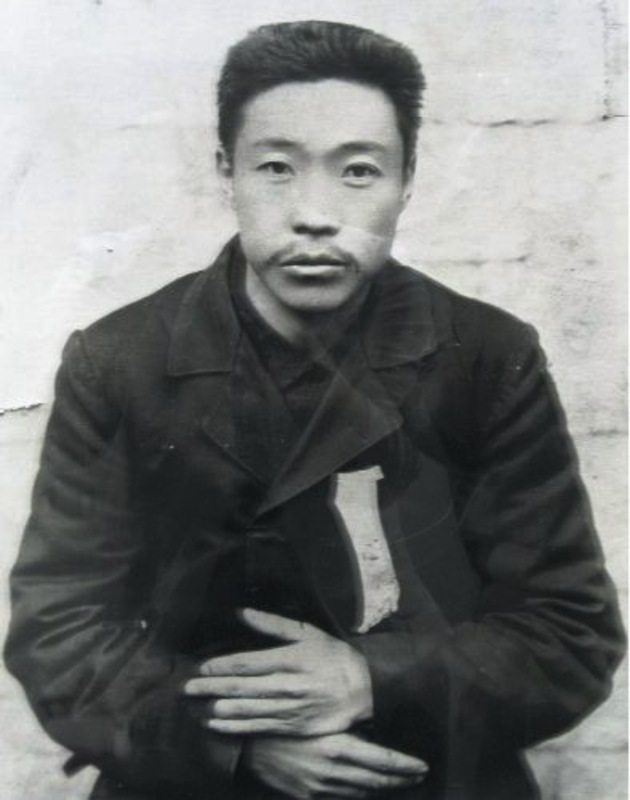

An Jeung-Gen before his execution |

News coverage has followed fairly predictable contours, largely focusing on the same statements issued by government spokespeople (China helps South Korea celebrate the assassin of a Japanese colonial official – The Economist; China & South Korea reject complaint from Japan about statue of assassin – South China Morning Post; S. Korean president proposes memorial of anti-Japanese hero in China – Asahi Shimbun; Which Japan is real? – Korea Times), However, my eye was particularly drawn to an article on the Japan Today website (China praises Korean assassin whom Japan calls “criminal”) which images of An: anti-Japanese hero and criminal. Noticeably absent in all of this is any thoughtful consideration of who An was or what might have driven him to shoot Itō.

To introduce the current conflict, Japan Today features the July 28 photo of Korean soccer fans unfurling two giant posters of An Jung-Geun (Ahn Jung-Geun in the original article) during an East Asian Cup match and goes straight to the much-quoted statement by Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson Hong Fei that, “Ahn Jung-Geun is a very famous anti-Japanese fighter in history.” The term anti-Japanese carries multiple resonances here. Hong alludes to An’s struggle for Korean independence even as his words echo Chinese terminology for its eight-year war with Japan (1937-1945). For their part, the Korean soccer fans who unfurled the An posters likely intended their act in a broadly anti-Japanese manner.

Interestingly, a survey of An’s writings and his interrogation and trial transcripts turns up little that is anti-Japanese in this broad sense. In fact, An invariably referred politely to the Japanese Emperor and avoided criticism of the Japanese people and government as a whole. In the fifth session of his trial (February 12, 1910), An justified his killing of Itō by arguing that he was protecting Japanese people who had been hurt by Itō’s policies. An recounted in his autobiography that he and his father had been recognized by a Japanese military officer for their efforts in putting down the Donghak Rebellion (1894-1895) against the Qing dynasty.

|

Ito Hirobumi on Japan’s 1,000 Yen note |

Popular images of An dwell on the actual killing of Itō, ignoring what An hoped to gain by doing so. According to his autobiography, after his arrest, a Japanese prosecutor asked him why he had killed Itō. An explained that Itō had tricked the Japanese Emperor into believing that everything in Korea was going smoothly and that Koreans approved of the protectorate that Japan had established there in 1907 when in fact a violent conflict raged on the peninsula. An then told the prosecutor, “Please quickly inform His Majesty the Emperor of what I have said. It is my hope that Itō’s evil policy can be rectified and the East rescued from its precarious position.” An believed that Itō had tricked the Japanese Emperor and was a rogue official following his own policy. Now that he was disposed of and his “lies” had been revealed, An believed the Meiji Emperor would reform his country’s policy. Killing Itō was, in short, not An’s final goal, but a means toward that goal. Since An actually succeeded in killing Itō, it is that act which receives the most attention. However, such a focus obscures why An acted as he did, allowing people to project their own anti-Japanese feelings on to his motives.

|

Korean Soccer fans unfurl An Jeung-Geun poster |

An’s post-trial statements during a hearing about a possible appeal provides a better understanding of how he viewed Japan. As he put it, “Japan’s position in East Asia can be likened to the head of a person” and “Korea, China, and Japan are like brothers in the world and therefore they should be closer to each other than to anyone else.” Based on these ideas, An presented a plan for a loose confederation, in which China, Japan, and Korea would cooperate with each other economically and militarily allowing the three countries to develop while each maintained its sovereignty. An believed that Japan should take the lead since it had successfully modernized. Rather than being anti-Japanese or desiring to defeat Japan, An hoped China and Korea could be friends with Japan while enjoying autonomy and cooperation.

South Korea’s ministry spokesperson Cho Tai Young’s statement in the same Japan Today article that “Martyr Ahn sacrificed his life not [only?] for the country’s independence but for regional peace as well” therefore provides a fairly accurate account of An’s own concerns. This is in fact the position of An’s official memorial organization in Korea (it manages An’s memorial hall as mentioned in the article), which is careful to include Japanese representatives in conferences and memorial services dedicated to An. (By contrast, many unofficial organizations focus more on An as a means of unifying North and South Korea). However, what is omitted is the fact that the foundation of An’s thought was regional peace and Pan-Asianism in particular, the belief that the “yellow race” should work together in order to protect itself from the imperialism of the “white race.” Further complicating matters is that during his appeal hearing, An explained that “if the emperors of the three countries of Japan, China, and Korea were to meet with the Roman Pope, take their oaths together, and then be crowned by him, the world would be astounded by the news.” The legitimacy that papal coronation would bring to these East Asian nations would prevent Western countries from threatening them, An believed, leading not only to peace in the region, but throughout the world. As a devout Catholic who often looked to European priests for guidance, it is no surprise that An would seek to incorporate the pope into his plans, though it is certainly not something that most Pan-Asianists would do. This, and the fact that the nationalist An would look to Japan for help in building up Korea and China, is a testament to the complexity of the times An lived in and the tensions within his own thought.

In contrast to these positive Chinese and Korean images of An, Japanese Chief Cabinet Secretary Suga Yoshihide described him as a “criminal.” An was of course found guilty of murder by the Kwantung (Japanese) Government-General District Court. However, this simple image of An the convicted assassin ignores the problematic legal processes that resulted in the court’s verdict. First, An killed Itō on territory claimed by the Qing Empire that was administered by Russia. Consequently, much of An’s trial was devoted to arguments over whether Japan did indeed have jurisdiction in the case. Such legal arguments arose from the fact that the Russians, who had arrested An and who were seeking better relations with Japan, decided to turn him over to the Japanese consul in Harbin almost immediately after taking him into custody. Moreover, the trial itself, held in Port Arthur (Ryojun/ Lüshun) was a show trial. It was incredibly short (it met only for six sessions, with each lasting a single day or less) and each time that An was given the opportunity to speak he was pressured to be brief. Moreover, the trial was conducted completely in Japanese, with An only given a brief outline in Korean of what was being said. He was assigned two Japanese defense lawyers, which was presented as a benevolent act that went beyond the requirements of Japanese law. The lawyers provided An a competent defense (for instance, An was compared to the heroes of Imperial Restoration in Japan who had used violence to overthrow the Tokugawa state). They did not, however, provide him with the defense he wanted—that Itō’s actions in Korea were themselves criminal and that An had, therefore, acted justly in using violence against him. Moreover, the Foreign Ministry had ordered the judiciary to find An guilty and assign the death penalty before the trial had even begun.

An’s conviction was useful for justifying Japan’s colonization of Korea. If An was a criminal, then Itō was an innocent victim and, extending the logic, his policy of colonization was likewise legal. Consider the list of Ito’s crimes compiled by An for his defense:

1) The crime of killing Empress Min (An incorrectly thought that Itō had ordered the killing since he was prime minister when it occurred in 1895)

2) The crime of forcing the Emperor of Korea (Gojeong) to abdicate

3) The crime of forcing the conclusion of the five- and seven-article treaties

4) The crime of slaughtering innocent Koreans

5) The crime of forcibly seizing political power

6) The crime of seizing railroads, mines, and land

7) The crime of forcing the use of the paper money issued by the First Bank

8) The crime of disbanding the Korean army

9) The crime of obstructing education

10) The crime of preventing Koreans from being educated overseas

11) The crime of confiscating and burning textbooks

12) The crime of deceiving the world by saying that Korea wanted to be protected by Japan

13) The crime of tricking the emperor [of Japan] into thinking that things in Korea are peaceful and without incident when in fact between Korea and Japan there is no end of war and slaughter

14) The crime of destroying peace in the East

15) The crime of killing His Highness the Japanese Emperor’s father, the former emperor (Kōmei).

By listing these crimes, An presented Japan’s colonization of Korea as illegitimate. Itō is presented as having forcibly taken over the state, making it into his puppet (according to his autobiography, An said as much to a group of pro-Japanese Ilchinhoe followers who kidnapped him for a brief period, declaring “The so-called Korean government is one in name only. In reality, it is Itō’s private state. Koreans who obey the government’s orders are really obeying Itō.”) Yet, while An contended that Itō had to be killed, he had to argue how he could legitimately wield lethal violence. He did this during his third trial session (February 9, 1910), stating that “For three years I have been traveling about encouraging the people [to join the Righteous Army] and I also fought as a lieutenant-general in this [Righteous] Army. I committed this evil act (the word “evil” appears in the transcripts but was probably added by the Japanese interpreter) as a lieutenant-general in the Righteous Army engaged in a war of independence and not as a common assassin. For this reason I am now on trial but I maintain that I am not a common criminal but a prisoner of war.” An’s words, spoken through an interpreter at trial, are rough, but he is making an important point—since Itō had illegally seized control of the Korean government under the guise of legal treaties, An and other Koreans had taken up arms on behalf of a government that could no longer protect them, or even itself, thereby appropriating the state’s right to legitimately utilize lethal violence. In this way, in an early formulation of the right to rebel exercised by anti-colonial movements throughout the long twentieth century, he challenged the foundations of the Japanese colonial project in Korea. Despite the loss of that empire with its defeat in 1945, judging by the reaction of the current Japanese government, this man, dead for a century, still poses a challenge today.

Though it could only happen if there is a willingness by the governments involved to shift from the above portrayals of An, if the statue is indeed erected, it should include quotes from An’s actual writings on its base, and souvenir stands nearby should make available editions of his works in Korean, Chinese, Japanese, English and other languages, so that people can learn about An and the difficult time he lived in through his own words. In particular, one of the most important lessons An has to teach is that when law becomes a weapon used to justify the power of the strong, rather than a shield to protect the weak, only chaos, conflict, and violence follow. And that is a lesson not just for the people of East Asia, but for all humanity.

Franklin Rausch is an assistant professor of history at Lander University (Greenwood, SC, USA). He and Jieun Han (a PhD. candidate in Church History at Yonsei University) are currently translating An Jung-Geun’s writings and related historical documents with the support of Yonsei University. Their introduction to and translation of A Treatise on Peace in the East can be found at http://www.utoronto.ca/csk/Intro_for_A_Treatise_on_Peace_in_the_East.pdf andhttp://www.utoronto.ca/csk/A_Treatise_on_Peace_in_the_East.pdf. Rausch authored a related article at Acta Koreana on “Visions of Violence, Dreams of Peace: Religion, Race, and Nation in An Chunggŭn’s A Treatise on Peace in the East.” –Main Site).

Recommended citation: Franklin Rausch, “The Harbin An Jung-Geun Statue: A Korea/China-Japan Historical Memory Controversy,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 11, Issue 48, No. 2, December 2, 2013.

Related articles

• Mikyoung Kim, Human Rights, Memory and Reconciliation: Korea-Japan Relations

• Tessa Morris-Suzuki, Migrants, Subjects, Citizens: Comparative Perspectives on Nationality in the Prewar Japanese Empire

• Tessa Morris-Suzuki, When is a Terrorist not a Terrorist?

• Peter Dale Scott, Norway’s Terror as Systemic Destabilization: Breivik, the Arms-for-Drugs Milieu, and Global Shadow Elites

• Yuki Tanaka, Japan’s Kamikaze Pilots and Contemporary Suicide Bombers: War and Terror

For those interested in reading An’s autobiography and Treatise on Peace in the East in modern Korean (the documents were originally written in Classical Chinese), there are multiple editions in print. An excellent critical edition, which includes both a modern Korean translation and the original Chinese, is Yun Pyong Suk [Yun Pyŏngsŏk], ed. and trans., An Chunggŭn chŏn’gi chŏnjip [The collected autobiographies of An Chunggŭn]. Seoul: Kukka Pohunch’ŏ, 1999. For trial transcripts, there exist the stenographic notes of a Japanese journalist who observed the trial directly. Summaries of his transcriptions were published in the Manshū nichinichi shimpō[Manchuria daily news], and the transcriptions themselves were published on March 28, 1910 as a book entitled An Jūkon jiken kōhan sokkiroku [Stenographic records of the trial of the An Chunggŭn incident] by the same paper. Dr. Sin Unyong has published editions of both the stenographic transcripts and the official government ones (the stenographic versions are more complete and include the judge pressing An to hurry, something the official version leaves out). Sin’s volumes include reproductions of the Japanese originals, printed Japanese transcripts, and modern Korean translations. See Sin Unyong, trans., An Chunggŭn sinmun kirok [The interrogation records of An Chunggŭn]. Seoul: Ch’aeryun, 2010 and An Chunggŭn∙Wu Tŏksun∙Cho Tosŏn∙Yu Tongha kongp’an kirok: An Chunggŭn sakkŏn kongp’an kirok sinmun kirok [The trial records of An Chunggŭn, Wu Tŏksun, Cho Tosŏn, Yu Tongha: the trial records of the An Chunggŭn incident]. Seoul: Ch’aeryun, 2010.