BY: Olena Kalashnikova, Fabian Schäfer

Abstract: There are two main ways Russian propaganda reaches Japan: (a) the social media accounts of official institutions, such as the Russian Embassy, or Russian state-linked media outlets, such as Sputnik, and (b) pro-Russian Japanese political actors who willingly (or unwillingly) spread disinformation and display a clear pro-Kremlin bias. These actors justify the Russian invasion of Ukraine and repeat the Russian view of the war with various objectives in mind, primarily serving their own interests. By utilizing corpus analysis and qualitative examination of social media data, this article explores how Russian propaganda and a pro-Russian stance are effectively connected with and incorporated into the discursive strategies of political actors of the Japanese Far-Right.

Keywords: Russian propaganda, Russo-Ukrainian War, Disinformation, Social media, Twitter, Far-Right, Corpus linguistics

Russian Propaganda and its Pro-Russian Proxies: An Overview

Russian state propaganda can be defined as the strategic communication effort orchestrated by the Russian government-controlled media to promote a specific worldview aligned with the Kremlin’s agenda (Paul and Matthews 2016; Oates 2016; Global Engagement Center 2020; Hodgson 2021). The primary goal of Russian foreign propaganda is to align public opinion abroad with the political and geo-strategic objectives of the current Russian government. Following the 2008 invasion of Georgia, when Russia recognized the importance of information warfare, the country restructured its propaganda apparatus on a global scale. As a result, Russian foreign propaganda is disseminated through various proxy actors and outlets, being key elements of Russia’s multi-layered propaganda strategy (Global Engagement Center 2020). Social media accounts affiliated with Russian official governmental bodies, such as the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and embassies, play a crucial role in this disinformation campaign, especially following the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 (Thompson and Graham 2022). Research conducted by Goran Georgiev (as cited in Alessandro 2023) has shown the extent of interaction between the Russian Embassy in Bulgaria and its Facebook followers. This level of interaction exceeded that of other Russian Embassy accounts in the Balkans despite the fact that those accounts posted more content. The increased interaction with the posts of the Russian Embassy in Bulgaria was associated with frequent mentions of the embassy in Sofia by local media outlets, according to the study. In Japan, the Embassy of the Russian Federation has 11,000 followers on Facebook and 93,900 followers on X/Twitter,12 thus standing out as “one of the ‘most influential’ among about 100 official accounts of the Russian government” in the world (Kanamori and Hatta 2022). The Russian Embassy in Japan provides content in Japanese, Russian, and English via these accounts.

Aside from the diplomatic outlets, Russian international (particularly RT and Sputnik) and domestic state-controlled news media and agencies (RIA Novosti, TV-Novosti, Pervyi Kanal,3 and TASS, to mention a few) play a pivotal role in Russia’s propaganda apparatus. RT, founded initially as Russia Today in 2005 and rebranded in 2009 under its new motto “Question More,” targets foreign audiences in multiple languages (Russian, English, Spanish, French, German, and Arabic). Sputnik, established in 2014, is an online news outlet publishing content in 28 languages, including Japanese. Multiple scholars have conducted comprehensive studies shedding light on the influence of disinformation campaigns orchestrated by these state-controlled media outlets in various European countries and Latin America, which are aiming at instilling distrust in local governments, the mass media, or academia by spreading fake news, disinformation, and conspiracy theories. In particular, Andreae’s (2022) study highlights the dissemination of fake news and disinformation by RT Germany, particularly concerning the COVID-19 pandemic and climate change. Yatsyk (2022) extended this focus to other European countries, while Spahn (2021) delved into the disinformation campaigns carried out by RT Germany during critical political events, such as the national elections in 2017, the Bavarian elections in 2018, and the European Parliament elections in 2019. In a study of RT UK’s news coverage during the 2019 British General Elections, Kazakov (2022) revealed a clear bias in RT UK’s reporting. Yablokov’s (2021) analysis focused on the role of conspiracy theories in RT’s coverage, particularly concerning the COVID-19 pandemic and the 2020 US Presidential elections. Iriarte (2022) studied the dissemination of conspiracy theories related to various geopolitical events in Latin America in RT’s Spanish language program, including the implication that the USA and Colombia were playing a role in the assassination of Haiti’s President Jovenel Moïse. Furthermore, Orttung and Nelson (2019) provided insights into RT’s content strategies on YouTube, emphasizing its role in disinformation campaigns aimed at Russian-, English-, and Spanish-speaking audiences. Toepfl et al. (2022; 2023) conducted a study aimed at identifying the plotters behind COVID-19 conspiracy theories and their representation in search results across different countries. In particular, the study showed that, within five distinct national contexts and two languages (Russian and English), webpages affiliated with the Kremlin were nearly five times as likely as non-Kremlin-affiliated pages to propagate unsubstantiated conspiracy theories. Notably, these Kremlin-affiliated pages stood out as the sole sources to suggest U.S. involvement in orchestrating the pandemic. A related study showed the role of the Kremlin-controlled search engine Yandex in displaying COVID-19 conspiracy theories in the search results (Kravets et al. 2023). Another study by Kling et al. (2022) sheds light on the global impact of the website and mobile app audiences of RT and Sputnik across 21 countries.

Following the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the European Union took action by suspending the broadcasting activities of Sputnik and RT, which included RT English, RT UK, RT Germany, RT France, and RT Spanish, within its boundaries on March 2, 2022 (Council of the EU 2022). Subsequent measures were enforced by Meta to block RT and Sputnik in the EU (Peters 2022), and a global ban was implemented by YouTube (Clark 2022). Nevertheless, the complete prevention of disinformation dissemination within the EU proved elusive. The Institute for Strategic Dialogue (ISD) conducted a comprehensive analysis, revealing various tactics and loopholes employed by RT to circumvent the ban and spread false claims about the war in Ukraine across the internet. These tactics included the creation of mirror websites (Balint et al. 2022) and accounts on platforms like YouTube (Thomas 2022) or TikTok (O’Connor 2022). Additionally, RT engaged in disseminating Russian propaganda, particularly within German-speaking and French-speaking (Adamczyk and Morinière 2021) social media accounts that spread conspiracy narratives and misinformation, such as those related to COVID-19. In the context of Germany, according to an analysis by Smirnova et al. (Smirnova, Matlach, and Arcostanzo 2022; Smirnova and Arcostanzo 2022), RT DE maintained popularity as a news source used in Telegram channels and Facebook groups that disseminated far-right extremist and conspiracy narratives in the German language. Additionally, both studies point out that independent news channels play a role in disseminating disinformation by sharing news articles copied from RT or Sputnik.

Furthermore, RT orchestrated a disinformation campaign aiming at discrediting Ukrainian refugees (“Deutsche Wahrheit: A pro-Kremlin Effort to Spread Disinformation about Ukrainian Refugees” 2022) or raising doubts regarding Russian atrocities in Bucha (“On Facebook, Content Denying Russian Atrocities in Bucha Is More Popular than the Truth” 2022). Furthermore, the ongoing spread of propaganda has intensified in other regions as well, notably in Latin America. According to Brandt and Wirtschafter (2022), Russian state media’s content is disseminated through independent Spanish-speaking journalists, in addition to Russian diplomatic social media accounts and RT Spanish.

In the case of Japan, Russian state-controlled propaganda is mainly disseminated via the Japanese language version of Sputnik. The Twitter account of Sputnik Japan (@sputnik_jp)4 was established in February 2012 and has 100,900 followers as of autumn 2023. Additionally, another Russian media presence in Japan, Russia Beyond, focuses on offering lifestyle and culture-related news about Russia that, together with Sputnik, is strategically tapping into shared cross-cultural interests such as figure skating, ballet, and martial arts, to foster a connection with the Japanese audience. Brown (2021) and our preliminary research in 2022 indicate that these cultural topics receive more coverage in Sputnik Japan than in their English counterparts. However, Brown did not identify explicit propagandistic efforts by Sputnik Japan to portray Russia favorably before 2021. Research on the impact of state-controlled Russian propaganda in Japan is still scarce.

Despite the ban of the aforementioned media outlets, another gear of the Russian propaganda machinery is still effectively working, namely so-called “proxy agents.” These include foreign media outlets affiliated with Russia, such as Global Research,5 but more importantly, local Russia-friendly institutions and political figures acting as disseminators of pro-Russian views (Global Engagement Center 2020). In the European context, one prominent example of these proxies is Hungarian state-linked media, including the Hungarian Telegraph Office, known for disseminating pro-Kremlin narratives (Balint 2022; Rankin 2022). In Japan, Russian proxies include parties and individuals, ideologically ranging from the right (such as Muneo Suzuki or the extreme-right party Issuikai, which will be discussed in this paper) to conservatives, such as former PMs Yoshirō Mori6 (LDP), and the political left, such as Yukio Hatoyama (DPJ).7 Moreover, lobbyists and diplomatic institutions, such as the Japan-Russia Friendship Association or the Tokyo representative office of Rossotrudnichestvo (The Federal Agency for the Commonwealth of Independent States Affairs, Compatriots Living Abroad, and International Humanitarian Cooperation), act as proxies.

We understand proxies not as official agents of the Russian state (such as embassies), but as relays or multipliers who actively propagate pro-Russian content and thereby are complicit in supporting the actions of the current government. For instance, Suzuki Muneo, Mitsuhiro Kimura (Issuikai’s leader), and Yukio Hatoyama participated in events organized by the Russian Federation Embassy in Japan, including the Russia Day Reception (“Reception on the Occasion of Russia Day Held at the Russian Embassy in Tokyo” 2022). Moreover, during his recent visit to Moscow in October 2023, Suzuki met with Konstantin Kosachev, the Federation Council Deputy Speaker, and other officials (TASS 2023), which led to his leaving Nippon Ishin no Kai (see below). Kimura also visited Moscow in October 2023, where he met with Vladimir Dzhabarov, the First Deputy Chair of the Federation Council Committee on Foreign Affairs (“Vladimir Dzhabarov Meets with Chair of the Japanese Civic and Political Organisation Mitsuhiro Kimura” 2023), and attended the Yalta International Forum (Twitter.com @issuikai_jp).

Screenshot 1. Suzuki attending the Russia Day Reception in Tokyo on June 9, 2022 (Source: Facebook account of The Embassy of the Russian Federation in Japan)

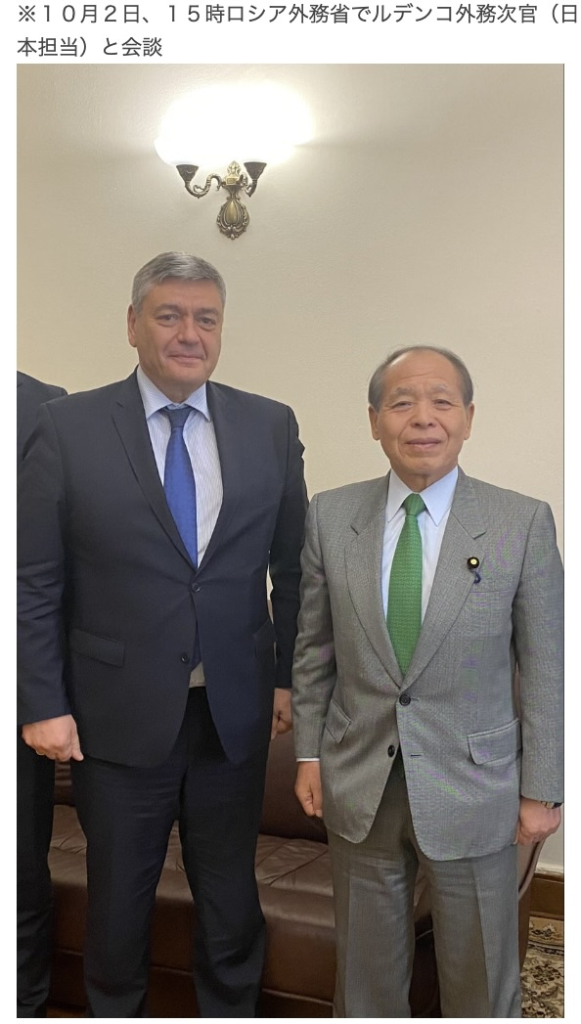

Screenshot 2. Suzuki meeting with Grigory Karasin, Chairman of the Federation Council Committee on International Affairs of the Russian Federation, in Moscow on October 4, 2023 (Source: Suzuki’s blog on Ameba Blog)

Screenshot 3. Suzuki meeting with Andrey Rudenko, Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, in Moscow on October 4, 2023 (Source: Suzuki’s blog on Ameba Blog)

Screenshot 4. Suzuki meeting with Konstantin Kosachev, Deputy Speaker of the Federation Council of the Russian Federation, in Moscow on October 4, 2023 (Source: Suzuki’s blog on Ameba Blog)

Screenshot 5. Kimura meeting with Vladimir Dzhabarov, the First Deputy Chair of the Federation Council Committee on Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, in Moscow on October 26, 2023 (Source: Issuikai’s account on X)

Screenshot 6. Kimura attending the Yalta International Forum in Moscow held on October 23-24, 2023 (Source: Issuikai’s account on X)

As it should have become clear from this literature review, Russia employs a multi-layered global propaganda strategy. The utilization of multiple channels is crucial in the effective spread of propaganda and disinformation. Diversifying sources adds a layer of complexity to the dissemination, making it challenging for audiences to discern the authenticity of the information and for investigative authorities to counteract these activities. By employing a multi-channel approach (diplomatic institutions, state-controlled media, and pro-Russian proxies), content is tailored to suit the preferences of different audiences and reach individuals across social media, traditional news outlets, online forums, and other communication platforms.

Methods and Data: Social Media and Mixed-Methods Approach

Our study uses data collected from Muneo Suzuki’s Facebook account, cross-posts from his Facebook content onto his “Muneo Diary” on Ameba Blog8, and Issuikai’s X/Twitter account.9 This data was gathered before and after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022 (cf. Table 1 for an overview of the collected data). Our mixed-method approach combines qualitative and quantitative analysis (manual and corpus-linguistic). This comprehensive methodological framework is applied to examine the collected posts and tweets, aiming to provide a nuanced and holistic understanding of the discourses presented online by these actors.

Table 1. Account activity and collected data10

| Actor | Channel Name | Followers | Created | # of Tweets/ Posts | Collected corpus | 24.02.2022-31.12.2022 corpus | Posts related to Ukraine |

| Muneo Suzuki | daichi.suzuki.muneo (FB) | 19243 | Jan 2013 | N/A | 1499 (17.07.2019 – 31.12.2022) | 362 | 129 |

| official_s_mune (Tw) | 17500 | Jul 2019 | 2281 | ||||

| 鈴木宗男 (Ameba blog) | NA | May 2013 | 3659 | ||||

| Issuikai | @issuikai_jp (Tw) | 47700 | Dec 2011 | 6636 | 5538 (15.12.2011- 31.12.2022) | 769 | 226 |

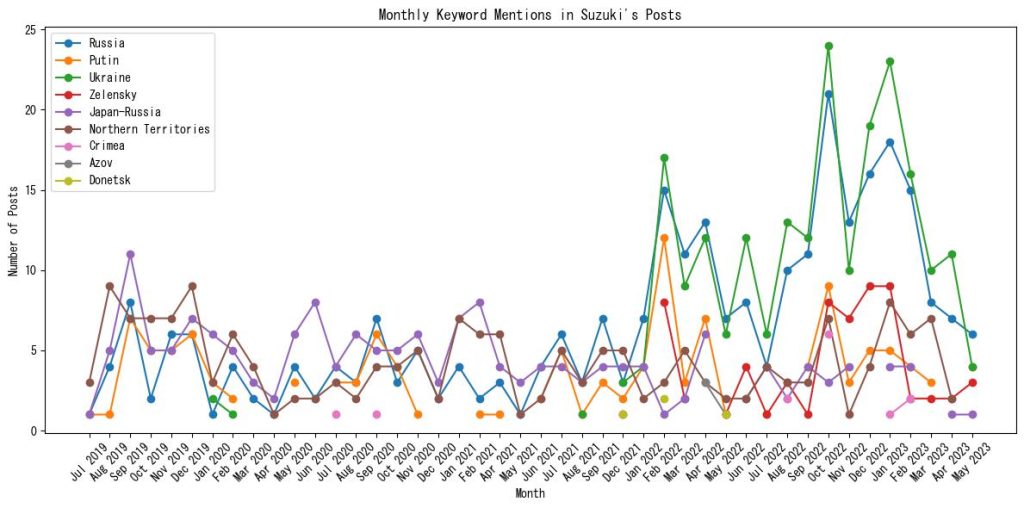

The data gathered before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine was specifically utilized to analyze the frequency of mentions of Ukraine and Russia-related terms. This comparative analysis aimed at uncovering shifts in the content surrounding these topics before and after the full-scale invasion. Figures 1 and 3 give an overview of the results of our analysis.

Based on the collected data (from the period February 24–December 31, 2022), we built corpora and used the corpus analysis tool AntConc.11 This method involves extracting and examining frequent keywords12 and linguistic patterns13 to identify recurring topics (cf. table 2 and table 3) to provide a snapshot of consistently addressed subjects. Moreover, we can show how certain topics are ideologically framed by analyzing linguistic patterns, such as specific terms, phrases, and rhetorical devices.

In the qualitative part of our analysis, we analyzed keyword-filtered14 posts related to Russia or Ukraine published during the period of our study. This microscopic analysis allows for a comprehensive examination of the content of posts, providing qualitative insights into the underlying meanings and contextual narratives utilized by each political actor. By manually classifying and calculating the different narratives, this method allows for a nuanced understanding of the content that may not have been evident through quantitative measures alone. The combination of both quantitative and qualitative methods provides a more holistic and comprehensive insight into the discourses surrounding Russia and Ukraine in the specified timeframe. We have already effectively applied and refined this mixed-methods approach in other research projects (Heinrich et al. 2018; Kalashnikova and Schäfer 2020; Fuchs and Schäfer 2020).

Analysis: Japanese Political Actors as Pro-Russian Propaganda Proxies

We define pro-Russian proxies as those who refuse to condemn Russia’s breach of international law and openly support or align with Russia’s interests and policies under the current government, particularly after pivotal events, including (a) the annexation of Crimea and the outbreak of the war in Donbas in 2014 and (b) the Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. We consider these two events historical turning points that have effectively alienated Russia from the global community, thus offering opportunities for pro-Russian actors to potentially reconsider and revise their Russia-friendly positions. In Japan, a small number of politicians have been actively advocating for Russian interests over the past two decades (Brown 2023). Those we consider pro-Russian actors still advocate the Russian cause despite the aforementioned watershed events, and their advocacy ranges from demands to establish and maintain stronger diplomatic and economic ties, to highlighting cultural affinities between Japan and Russia, to openly expressing positions that are favorable to Russia’s perspective on international issues.15

In our analysis, we focus on the dissemination of pro-Russian narratives via the respective social media accounts of politician Muneo Suzuki (member of the right-leaning populist party Nippon Ishin no Kai until October 2023) and the far-right political party Issuikai.

Quantitative analysis: The Language of Pro-Russian Actors

Muneo Suzuki: Russo-Japanese Friendship Lobbyist

Muneo Suzuki, a Japanese politician, has been a member of the House of Councillors since 2019. Although he was previously affiliated with Nippon Ishin no Kai, he left the party before facing expulsion due to a recent visit to Moscow from October 1–5, 2023 (Kyodo News 2023). Suzuki is known for his pro-Russian stance and efforts to improve Russo-Japanese relations, as well as his active participation in various diplomatic initiatives regarding the disputed Kuril Islands (Ferguson 2008). Moreover, Suzuki was also an unofficial adviser on Russian affairs to former PM Shinzō Abe (Suzuki 2018) and frequently appears as a Japanese expert in Russian state media.

Suzuki wielded significant influence within the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA). He has had a close relationship with former Japanese diplomat Satō Masaru16, who held key positions in the MOFA, including the position of the Third Secretary of the Embassy of Japan in Russia. The two met in the 1990s and shared a vision for advancing Japan’s interests, particularly in Russo-Japanese relations. According to Brown (2019a), Sato received his position as a Chief Analyst at the International Intelligence Bureau in MOFA with the help of Suzuki, and ended up providing Suzuki with insider information and helping to expand Suzuki’s network within the Russian political elite. However, their relationship became strained after Satō’s scandal involving allegations of improper conduct (Mulgan 2010). Furthermore, Suzuki’s daughter, Takako Suzuki, who, according to Brown (2019b), secured her role within the Ministry of Defence in 2018 presumably through familial connections, held a high-ranking position in MOFA as the Senior Vice Foreign Minister from October 6, 2021, to August 12, 2022. She faced criticism for opposing sanctions against Russia after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine (Shūkan Bunshun 2022).

As can be seen in figure 1, there was a noticeable increase in Muneo Suzuki’s Ukraine-related posts on Facebook after the full-scale invasion, with the most significant surge taking place between August 2022 and February 2023. It is worth noting that keywords associated with Japan-Russia relations (日露), experienced a decline in frequency in his posts starting in 2021. In contrast, the term “Northern Territories” (北方領土) saw a rise in the second half of 2022, which may be attributed to the annual commemoration of Northern Territories on February 7, 2023, following the pattern seen in previous years.

Figure 1. Ukraine/Russia-related terms in Suzuki’s Facebook posts over time

As for Muneo Suzuki, our analysis shows that among the 100 most frequent keywords (cf. table 2) those directly related to the 2022 Japanese House of Councillors election, held on July 10, played a very prominent role. Another cluster of keywords contains geographical places related to Hokkaidō as Suzuki is a Diet member coming from that region. Other notable topics include the war in Ukraine, territorial disputes (a constant topic in Suzuki’s discourse), and references to national and international political leaders, particularly Zelenskyy and Putin, the two most frequently mentioned foreign leaders.

Table 2. Top 100 keywords in Suzuki’s corpus (February 24, 2022- December 31, 2022)

| Category | Keywords |

| Elections | Election (選挙), restoration (維新), Suzuki (鈴木), candidate (候補), Hatta (八田), Morishige (もりしげ), Satoru (さとる), ward (区), councilor (議員), Kobayashi (小林), speech (演説), conviction (信念), senator (参議), proportional (比例), nationwide (全国), administrative division (管内), support (後援) |

| Political actors | Prime Minister (総理), president (大統領), minister (大臣), Kishida (岸田), Zelenskyy (ゼレンスキー), Abe (安倍), leader (首脳), Putin (プーチン) |

| Locations (Hokkaidō) | Hokkaidō (北海道), Kushiro (釧路), Chihiro (千春), Sapporo (札幌), Nemuro (根室), Obihiro (帯広), Asahikawa (旭川) |

| Countries | Ukraine (ウクライナ), Russia (ロシア), Japan (日本), America (アメリカ) |

| International Relations | Diplomacy (外交), foreign affairs (外務), committee (委員), territory (領土), Northern (北方), relations (関係) |

| Military conflicts | Ceasefire (停戦), war (戦争), aid (供与), conflict (紛争), sanctions (制裁), history (歴史) |

| Media | Newspaper (新聞), report (報道) |

| Other | Citizens (国民), national interest (国益), responsibility (責任), parliament (国会) |

Interestingly, the term “ceasefire” (停戦) is the most frequently occurring term in our corpus. Suzuki strategically employs the concept of a ceasefire, ostensibly for humanitarian reasons such as preserving innocent lives and by alluding to Japanese pacifism.17 In fact, he is a strong advocate against the provision of arms to Ukraine. At the time, however, Putin did not envisage a ceasefire as a real option for concluding this war (a proposed ceasefire for Orthodox Christmas from January 6 to 7 merely had strategic reasons).18 Inverting the progress of events, Suzuki argues that, “since Ukraine is the one that caused Russia’s special military operation, Ukraine should agree to a ceasefire”19 in a post of October 23, 2022. Moreover, he opines that by providing arms and financial aid to Ukraine, the West only prolongs the war, since Ukraine would agree to a ceasefire once aid stops. Finally, Suzuki argues that the war in Ukraine threatens Japan’s and the world’s economies and should, therefore, be ended as soon as possible. By inappropriately comparing the situation of Ukraine (the defender in this war) with Japan (the historical aggressor in WWII), Suzuki explicitly calls for Ukraine to surrender in order to avert damage to the Japanese and global economies in a prevaricating post published on September 15, 2022:

The yen depreciation is progressing, various prices are rising, and there is concern about the impact on the Japanese economy and the global economy. First and foremost, it is crucial to bring about a ceasefire in the conflict in Ukraine.

Even if Ukraine claims to have regained 8,000 square kilometers of land, there has been no significant change in the war situation. If they cannot fight independently, they should seek a peaceful resolution.

77 years ago, Japan, driven by hardliners in the army, said things like ‘a hundred million will be prepared to die’ and ‘fight with bamboo spears against the United States.’ What were the results? We must not let Ukraine repeat Japan’s mistakes.

77 years ago, if Japan had surrendered six months earlier, there would have been no Tokyo air raids, no Battle of Okinawa, and no atomic bombings on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Before saying brave things, staying calm and looking forward is important. I think there is something Japan should do.20

Furthermore, in advocating for the disruption of financial aid, arms provisions, and sanctions on Russia, Suzuki strengthens his argument by endorsing false Russian claims that Ukraine (a) violated the Minsk agreements by conducting drone attacks on Russian-occupied territories on October 26,21 2021,22 and (b) was allegedly seeking nuclear weapons23 during Zelenskyy’s speech at the 58th Munich Security Conference on February 19, 2022 (cf. The Kyiv Independent 2022).

A closer look into the collocations of the term “Ukraine” (ウクライナ) in Suzuki’s posts reveals his stance on the war and aligns with the restrictions imposed by Russian authorities on discussing the aggression. Roskomnadzor (the Federal Service for Supervision of Communications, Information Technology, and Mass Media in Russia) and the Administration of the President of Russia imposed certain restrictions and guidelines on how the media and individuals should discuss sensitive topics, including using the term “special military operation” to describe the attack on Ukraine (RFE/RL 2022). Suzuki frequently uses terms like “issue” (問題) or “dispute” (紛争) instead of the term “war,” thereby downplaying the severity of the war, as well as “special military operation” (特別軍事行動). Additionally, Suzuki’s description of the attack on the Crimea bridge as a “deed” (仕業) suggests that he considers it not as a matter of a strategic military counterattack by the Ukrainian forces, but as a purposeful terrorist action by Ukraine to provoke further escalation, thereby supporting the Russian narrative of Ukraine as the “real” aggressor.

Other collocates related to weaponry, including the word “weapon” (武器), “drone” (ドローン), or “missile” (ミサイル), are consistently used in a way that portrays Ukraine as the aggressor. The term “weapon” (武器) is linked to the discussion of the provision of arms, along with financial aid, which allegedly contributes to prolonging the war (6 out of 12 instances). In 9 out of 10 instances of his uses of the term “missile” (ミサイル), Suzuki relates to an incident involving a missile fragment falling on Polish territory on November 15, 2022. He also uses this as evidence to support the argument that it is Ukraine that acts aggressively. Finally, in the majority of the occurrences of the term “drone” (ドローン) (11 out of 12), these are uniquely linked to Ukrainian drone attacks on pro-Russian residential areas in Ukraine (親ロシア住民地域), i.e., territories occupied by Russian troops since 2014, or Russian soil. Eight occurrences related to the drones mentioned in posts by Suzuki specifically mention the date “October 23, 2021.” It appears that there may be a discrepancy in the dates mentioned by Suzuki in his post, as no information corresponding to that specific date could be found. However, it is possible that Suzuki meant October 26, 2021, as mentioned above, in which case he repeated false information multiple times. The repetitive use of an incorrect date suggests that Suzuki might not be meticulous in fact-checking and verifying the details of the incidents he references to support his claims.

Moreover, Suzuki is imprecise in his language when referring to Russian territories or territories with a pro-Russian population. He interchangeably uses the terms “pro-Russian group” (親ロ派) or “Russians” (ロシア人), referring to the same group of people who live in the annexed territories of Ukraine, as can be seen in figure 2 (examples 6-10), serving the broader disinformation efforts related to the war.

Figure 2. Context of the term “drone” (ドローン) in Suzuki’s corpus

Issuikai: Pro-Russian Anti-Americanism

Issuikai is a Japanese far-right political organization known for its anti-American stance. It opposes American imperialism and advocates for the improvement of relations with Russia. It was established in 1972 and is one of the most prominent New Right organizations in Japan. The Japanese New Right movement emerged in the 1970s and is characterized not only as being conservative and nationalist, but also as having revisionist views on Japanese history and politics, including opposition to perceived foreign influence, in particular by the United States. The movement also advocates for a more assertive military, frequently raising questions about national defense, security, and territorial issues (Ito 2019).

Issuikai also has been known to have close connections with prominent far-right politicians in Europe, such as Jean-Marie Le Pen (National Front, France) or the late Vladimir Zhirinovsky (LDPR, Russia) (The Economist 2010; Moldovanov 2019). In the past, Issuikai has expressed sympathy with individuals or countries resisting the so-called US dominance, having openly endorsed authoritarian leaders like Saddam Hussein (Hall 2018). Similarly, Issuikai sees in Putin’s Russia and his territorial claims to Ukraine a form of resistance against US hegemony. Aligning with his outspokenness about his pro-Russian stance, Issuikai’s leader Mitsuhiro Kimura cooperated with the Russian regime on numerous occasions, including having acted as a “foreign observer” at illegitimate referendums and elections in the annexed territories of South Ossetia and Abkhazia (2010, 2019) and Crimea (2014), as well as the Russian presidential elections in 2018 (Shekhovtsov 2019). Moreover, he also visited Crimea together with Yukio Hatoyama in 2015 (cf. Kalashnikova 2024).

In Issuikai’s tweets, the most frequent keywords include “USA” (米国), “Russia” (ロシア), “Ukraine” (ウクライナ), “Prime Minister” (首相), and “anti-US” (対米).24 Issuikai’s central focus revolves around two main themes: (a) “US hegemony,” which is closely intertwined with content related to military conflicts (the Russo-Ukrainian war is frequently related to other wars in its posts, particularly those initiated by the US, as evidenced by the frequent use of the keyword “Iraq” (イラク)); and (b) Japan’s “sovereignty” vis-a-vis the USA. In the comments, Issuikai criticizes the dominance of the USA over Japan, highlighted by the phrase “US-led constitutional reform” (従米改憲), referring to a debate on a proposed constitutional amendment related to Article 9, which pertains to Japan’s Self-Defense Forces (“Amending Japan’s Pacifist Constitution” 2018). Another specific focus of Issuikai’s posts is the Russian-occupied territories of Ukraine, including Crimea and Donbas.

Table 3. Top 100 keywords in Issuikai’s corpus (Feb 24, 2022- Dec 31, 2022)

| Category | Keywords |

| Countries | USA (米国), Russia (ロシア), Ukraine (ウクライナ), country (国), Japan (日本), America (米), Ukraine(ウ), Russia (ロ), Iraq (イラク), Asia (アジア) |

| International relations | Japan-US (日米), security (安保), international (国際), ambassador (大使), Situation (情勢), diplomacy (外交), treaty (条約), United Nations (国連), embassy in Japan (駐日), peace (平和) |

| Political actors | Prime minister (首相), president (大統領), Abe (安倍), Kishida (岸田), Zelenskyy (ゼレンスキー), Biden (バイデン), Putin (プーチン), Hatoyama (鳩山) |

| US hegemony | anti-US (対米), system (体制), post-war (戦後), administration (政権), subordination(従属), comply(従)25 |

| Other events | State funeral (国葬) |

| Government | Administration (政権), politics (政治), parliament (国会), cabinet (内閣), Liberal Democratic Party (自民) |

| Issuikai proliferation | Forum (フォーラム), Kimura (木村), representative (代表), Reconquista (レコンキスタ), meeting (会議), Mishima (三島), Kaiko (恢弘), NMF, commemoration (追悼) |

| Military conflicts | Base (基地), defeat (打破), atomic bomb (原爆), Yokota base (横田基地), war (戦争), occupation (占領), ceasefire (停戦), NATO, Crimea (クリミア), military (軍事), army (軍), weapon (兵器), defense (防衛), nuclear (核) |

| Sovereignty | Sovereignty (主権), independence (独立), nation (国家), defense (防衛), patriotism (愛国), autonomy (自主) |

| Other | People (民族), martyr (烈士), professor (教授), shrine (神社), citizen (国民), election (選挙), democracy (民主) |

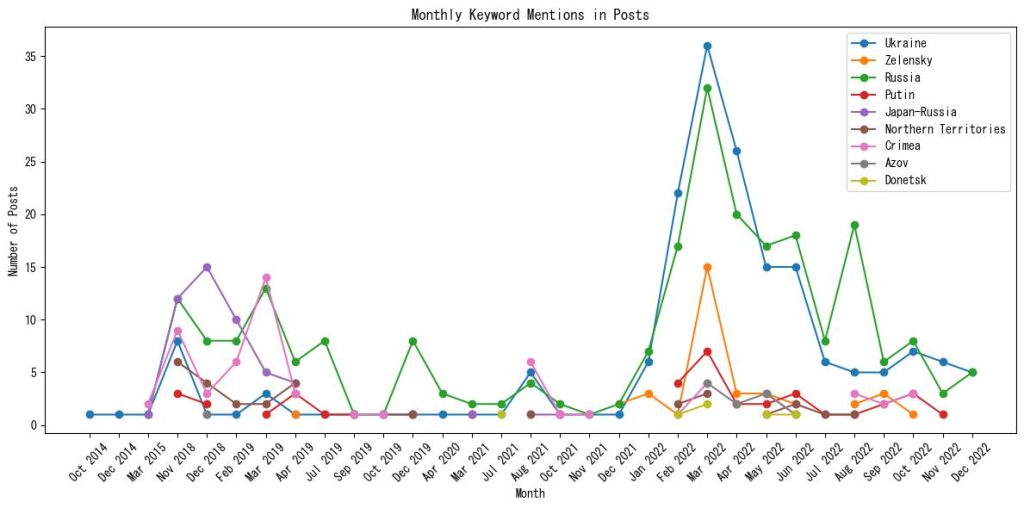

Issuikai’s focus shifted away from the war in Ukraine from around June 2022 (cf. figure 3). Moreover, as it becomes clear from figure 3 as well, another noteworthy peak of Russia-related keywords (green curve) in August is related to the commemoration of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bombings. Russia is mentioned in relation to its diplomatic efforts to address this historic event to highlight its adherence to non-proliferation treaties.

Figure 3. Keywords in posts over time in Issuikai’s tweets

The most frequent collocate in Issuikai’s posts frames the Russo-Ukrainian war by belittling it as “situation” (情勢) (23 instances), besides other trivializing terms such as “crisis” (危機) and “issue” (問題) (4 four instances each). Despite also using the word “war” (戦争) in 5 cases, 3 of them refer to the title of Masayuki Iwata’s26 talk at Issuikai Forum, which was entitled “Evaluating the Russo-Ukrainian war from the perspective of NATO’s invasion in Yugoslavia” (「NATO の ユーゴ 侵略 から ロシア ・ ウクライナ 戦争 を視る」). As one can already tell from the title of the talk, Iwata insinuates that NATO is playing a similar role in the war in Ukraine as it was playing in the civil war in former Yugoslavia (in which NATO was an active warring party, something that is considered controversial under international law). Other notable collocates of Ukraine include “military” (軍) and “eastern” (東部), often referring to alleged atrocities committed by the Ukrainian army, particularly in eastern Ukraine, such as attacks on civilians.

Qualitative Analysis: Pro-Russian Discourses in the Japanese Context

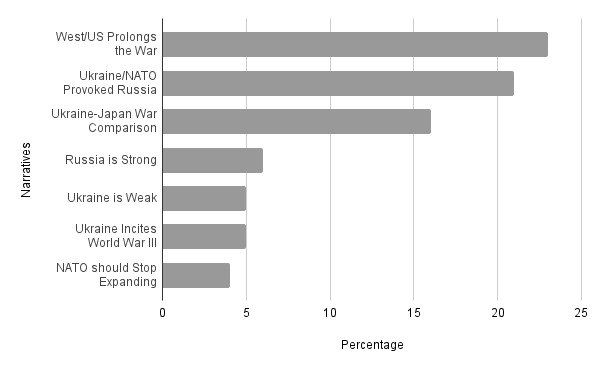

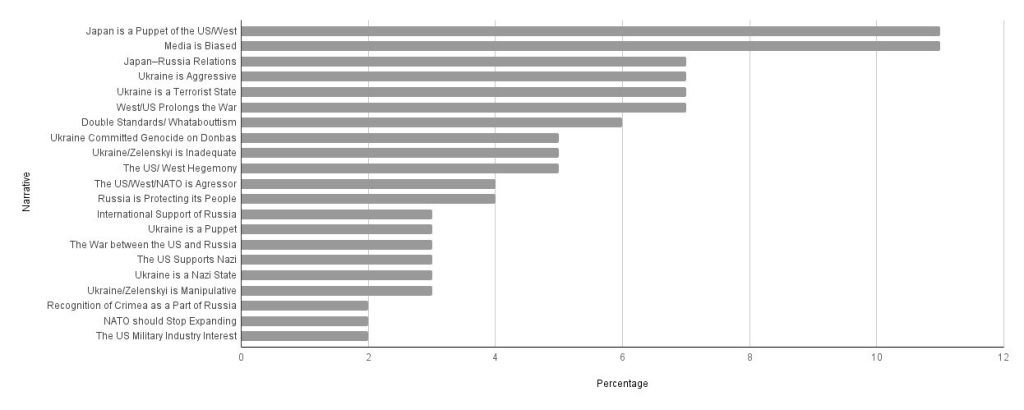

According to our study, Suzuki reproduces only a relatively limited number of pro-Russian narratives in his posts, especially if one compares his output to an extensive list of globally circulating Russian narratives provided by the DFRLab.27 By contrast, Issuikai disseminates a significantly broader array of pro-Kremlin narratives, and did so especially in the initial three months following the full-scale invasion. Figures 4 and 5 below outline the most popular narratives employed by each actor.

Moreover, Suzuki differs from Issuikai in terms of his stance towards the USA. As mentioned earlier, Suzuki—allegedly having been an advisor to former Prime Minister Abe on Russia-related issues—maintains a stance that does not overtly oppose the LDP’s party line with regard to Japan-American relations. In a post from May 23, 2022, he underscored the significance of Japan’s alliance with the United States while also underlining the importance of establishing “solid friendly and cooperative relationships with our neighboring countries.”28

By contrast, Issuikai, being in direct opposition to the ruling party, openly criticizes not only the economic policies of the current government, but also Japan-American relations, advocating for greater independence in foreign relations.

Figure 4. Pro-Russian narratives in Suzuki’s posts.

Figure 5. Pro-Russian narratives in Issuikai’s tweets.

The central narrative in Issuikai’s content revolves around its criticism of the Japanese government’s support for Ukraine, especially concerning Japan’s geostrategic alliance with the USA. Issuikai expresses concerns about Japan’s diminishing influence in the global arena due to a loss of sovereignty vis-a-vis the United States, even quoting Putin to fortify its criticism.29 Issuikai’s narrative underscores the negative impact of Western values on Japanese culture, often portraying Russia as a nation that defends its territorial integrity and cultural identity, a path that Japan should follow as well. This echoes the Russian justification of the invasion of Ukraine, which is based on the alleged differences in Western values that are deemed as “wrong” and, therefore, unworthy of consideration. The following tweet exemplifies Issuikai’s rhetorical strategy:

Many people seem to believe that the Ukraine incident is an opportunity to increase defense spending and return of the Northern Territories. How is it possible to claim that Russian political goals are ‘dangerous,’ but not have any concern about the dismantling of the spirit of Japan’s independence due to dependence on the United States? Everything, from Japanese thinking to culture, is about to be demolished. The Japan-U.S. relationship is not the only important aspect in the world.30

Issuikai frequently emphasizes what the party perceives as the alignment of Japanese media with Western “propaganda.” Their whataboutist criticism of Japan’s media extends to allegations of being biased against Russia, including accusations of Russophobia and perceived neglect of the alleged genocide in eastern Ukraine. It is also asserted that the Japanese media is biased by disproportionately highlighting issues in Ukraine while lacking empathy toward troubled nations in Asia or Africa. Additionally, Issuikai suggests that the Japanese population tends to align itself with Western nations, even though these nations are allegedly in the minority with respect to their position on current global military conflicts, implying that false values are prevalent in Japanese society.

Anti-Western narratives such as the “US/West prolongs the war”, together with other less frequent narratives such as “US/West supports the war,” “US/West hegemony,” “NATO expansion,” and “US supports Nazis,” are used to deflect responsibility for this war away from Russia and towards “the West” or NATO, which in turn turns the USA into an untrustworthy partner for Japan, merely seeking its own profit and therefore keeping Ukraine from peace negotiations. Issuikai’s tweets primarily aim at demonizing the USA and the pro-American Kishida government for aligning with US policies by, for instance, warning the Japanese government that “it is forbidden for the Japanese government to support terrorists,”31 pointing at Azov Regiment.32 By doing so, Issuikai adheres to a recognized style of Russian propaganda, namely promoting a positive image of Russia while undermining confidence in Western institutions. Moreover, Issuikai claims that the US profits from the expenditures on military equipment and seeks to profit from Japan as well as to entangle the country in regional conflicts, as can be seen in this tweet:

In the international situation, the US military-industrial complex is setting up various traps. In the West, NATO’s Eastern expansion provoked Russia into war. In the East, the situation has gotten tense with the ‘free territory’33 provocation. Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Japan through Yokota Air Base is a way to clarify the ‘master-servant’ relations between Japan and the US and preparation for emergencies. The scenario remains in favor of the US military-industrial complex.34

For Suzuki, the narrative “US/West prolongs the war” isthe most recurring anti-Western narrative, mentioned in 23% of posts concerning Ukraine. As previously discussed, Suzuki places substantial importance on declaring a ceasefire, seeing a potential role for the Japanese government in pursuing this goal. As part of this narrative, Zelenskyy is portrayed negatively for his request for more weapons instead of actively working towards establishing a ceasefire and thereby protecting the lives of civilians.

Narratives Discrediting Ukraine: Ukraine as Aggressive and Insidious

The prevalent narratives discrediting Ukraine in the analyzed data revolve around several key themes, including allegations that Ukraine (a) is committing genocide, (b) is aggressive towards its own population, and (c) has a government that is acting against the will of its own citizens. There is also the accusation that Ukraine has provoked Russia through operations such as the attack on the Russian-built Crimean bridge.

The focal point of Suzuki’s argument lies in Russia’s purported response to the assault on pro-Russian regions on October 26, 2021, which he incorrectly dates as October 23, 2021, as mentioned earlier. Furthermore, Suzuki accuses Zelenskyy of violating the Minsk agreement and striving after nuclear weapons, as was allegedly expressed in his speech at the Munich Security Conference on February 19, 2022 (see above).

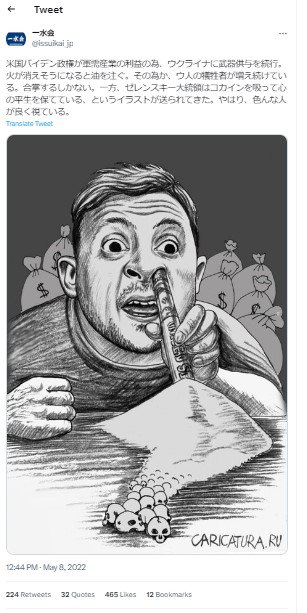

In Issuikai’s statements on Twitter, there is a notable emphasis on Ukraine’s alleged commitment to prolonging the war by seeking weapons. Additionally, Issuikai portrays Ukrainian soldiers as violating the Geneva Conventions and engaging in brutality, leading to the deaths of Ukrainian civilians. Issuikai’s claims include a denial of the Bucha atrocities committed by the Russian army. Furthermore, the Ukrainian government is depicted as corrupt, and Zelenskyy is portrayed as a crooked drug addict (see figure 6) and alcoholic. The aim of these statements is not only to discredit Ukraine, but also to discredit the international and Japanese mass media that hides these facts from the people, particularly atrocities committed by the Ukrainian army.

Similarly, Suzuki promotes his position by making unsubstantiated claims and insinuations, such as accusing Ukraine of being responsible for genocide in Donetsk, or the perpetrator of violence committed by the Azov Battalion without explicitly stating the nature of the alleged atrocities. Instead, he encourages his followers to investigate the information independently by urging them to “please look into the movements and actions of the Azov Battalion.”35 This approach shows how Suzuki avoids presenting verifiable facts to support his claims or being held accountable for specific claims, creating an atmosphere of conspiracy-triggering ambiguity by prompting his audience to do their own research. By encouraging readers to investigate with a predisposed attitude towards searched topics, Suzuki anticipates that they will discover information confirming the bias of his narrative, particularly with regard to the divisive Azov Battalion.

Figure 6. Issuikai’s tweet (1) including an image from the Russian caricature website called “Caricatura.ru”, showing Zelenskyy snorting a cocaine-like powder made of skulls through a rolled-up dollar bill.36

Moreover, by employing the narrative “Ukraine is a terrorist state,” Issuikai creates the image that Ukraine represents a global threat, particularly to both Asia and Japan. The claim that Ukraine is a threat is founded on the assumption that the country is potentially involved in the sale of military equipment to the Myanmar government, the production of North Korean missiles,37 and the trafficking of weapons provided by the West on the black market.

The use of the term “Slavic” (スラブ) in Issuikai’s tweets is particularly interesting, as the following tweet indicates:

The leaders of Germany, France, and Italy visited Kiev,38 Ukraine, and met with President Zelenskyy. It is fine to sympathize with the noble mission of defending one’s homeland, but the majority of soldiers who have lost their lives in battles in the eastern region are Ukrainians of Slavic origin, and this hints at the policy of the regime in Kiev to exterminate Slavic ethnicities. How far would the Anglo-Americans go to support this?39

By drawing a distinction between a “Slavic” and a “non-Slavic” Ukrainian population, this tweet frames the war in ethnic terms and raises questions about the treatment of the Slavic population within Ukraine. However, considering that Ukraine is predominantly a Slavic nation, with Ukrainians and Russians as the two major ethnic groups (Ukrainians at 77.8% and Russians at 17.3%, according to the 2001 census (“General Results of the Census. National Composition of Population” 2011), while other ethnicities make up only 4.9%, framing the war in ethnic terms is an attempt to allege the deliberate killing of the Ukrainian people by the government that, as implied, belongs to a different ethnic group. Moreover, the tweet highlights the war in eastern Ukraine and downplays the scale of the war after the full-scale invasion. While the narrative that “Ukraine commits genocide” condemns the Ukrainian government and army for alleged atrocities against the pro-Russian population and declares the aggression of Russia an act of self-defense, this framing inverts the Russian aggression into an ethnic war yielding an internal division within Ukraine.

A unique narrative in Suzuki’s social media content is the “Ukraine-Japan war comparison,” which accounts for 16% of his posts. By inappropriately comparing the contemporary situation of Ukraine with the historical one of Japan, he implies that Ukraine is the real aggressor, and that Ukraine should learn its lesson from Japan and surrender to prevent the (further) loss of territories (as it occurred with Okinawa in Japan’s case after the WWII) or even the threat of a nuclear strike. This rhetorical conversion shifts the war responsibility and further attacks onto Ukraine, implying that surrendering would be a way to avoid severe consequences.

Russia-Whitewashing and Responsibility-Denying Narratives

The narratives in Issuikai and Suzuki’s posts aim to portray Russia as a victim of aggression and emphasize the importance of protecting the Russian-speaking populations. This is particularly evident in Issuikai’s tweets, in which it is argued that the Crimean population willingly chose to join Russia and that the Ukrainian government sought to eliminate the Slavic population (cf. above).

The predominant Russia-whitewashing narrative in Issuikai’s discourse emphasizes the strong relationship between Russia and Japan, focusing on Russia’s esteem for the Japanese commemoration of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. This is reflected in the increase of Russia-related keywords in August 2022 (cf. figure 3). Additionally, Issuikai’s tweets also highlight the respect of the Japanese people for Russian soldiers (despite being enemies during World War II) and praise Russia for its resilience and achievements in the current war. The use of the term “patriotism” (愛国) (figure 7), which frequently appears in Issuikai’s content (see table 3), aims to fuse Russian and Japanese values and foster a sense of shared values between the two nations. However, as the tweet in figure 7 shows, this goes along with the manipulation of essential historical details in order to create a distorted historical narrative to praise Russia for its patriotism and its role in combating the Nazis during World War II.

The tweet assigns the credit for defeating Germany solely to Russia, ignoring the collective effort of the former Soviet republics and their sacrifices, including a substantial portion (40–44%) of the Ukrainian population. This historical revisionist oversimplification of a complex historical reality not only distorts rhetorical facts, but also reproduces a very common narrative of Russian propaganda, namely the self-image of Russia as the only legitimate successor of the Soviet Union.

Figure 7. Issuikai’s tweet of May 8, 2022 (2),40 consisting of the content discussed above and completely unrelated images (i.e. a screenshot of the account “Friends of Crimea,” of a woman stating that the enemy is not Russia but the Ukrainian Army and Azov Regiment, and of Denis Pushilin, the Head of the Donetsk People’s Republic, together with an unidentified man).

In Suzuki’s discourse, maintaining Japan-Russia relations is of utmost importance, particularly in economic and geopolitical matters. His posts highlight the potential consequences of Japan imposing sanctions on Russia, warning that such actions would likely lead to a deterioration in Japan-Russia relations. Suzuki advocates for the preservation of these relations for three primary reasons: (1) the urgency of establishing a Peace Treaty, (2) the importance of negotiations regarding the Northern Territories, and (3) the strategic advantage of maintaining positive relations with Russia to secure energy resources. Besides this “strategic” rhetoric, Suzuki also caters to the “Russia is strong”narrative. He consistently emphasizes Russia’s status as a “great power” (大国) and asserts that Russia possesses the inherent strength that guarantees victory over Ukraine. By contrast, according to Suzuki, Ukraine is reliant on the support of Western nations and incapable of standing on its own in the face of Russia’s might.

Discussion

Although it is hard to estimate the extent of their influence on social media, we believe that we have successfully demonstrated how certain political actors employ narratives aligned with pro-Russian propaganda. However, there might be more invisible and latent activities to influence public opinion on social media at work. Proxy agents spreading disinformation and conspiratorial content involve an indirect approach to influencing public opinion in favor of Russia. Since we do not have sufficient information on whether Japanese actors receive any form of remuneration for publicly adopting a pro-Russian stance, we need to ask ourselves how these actors could benefit from their actions. As we have seen from the two examples presented in this report, neither actors blatantly reproduce Russian propaganda, rather, they weave the pro-Russian stance into the existing narratives of their ideological and political views and agendas. Either they use their views on the war in order to reinforce their own pre-existing views on, for instance, the question of the northern territories in Hokkaidō, or they adopt views of the current Russian government to discredit allies of Ukraine, Western organizations, such as NATO, or “the West” in general. One can only understand this discursive strategy if one sees it in the context of what is commonly described as the “metapolitics” of the New Right in Europe.

The term, coined by key proponents of the European New Right (Alain de Benoit and Armin Mohler), describes the metapolitical discursive strategy of disseminating extremist ideas in the “pre-political” sphere of public discourse (including anti-feminist/sexist, xenophobic/racist, and/or anti-establishment agendas) through various types of “alternative” media (print publications or social media). The goal is to gradually “normalize” certain ideas and concepts in everyday language and political discourse that have hitherto existed only in the extremist fringes of discourse. In order to pursue their anti-establishment agenda, they often strategically disseminate disinformation and conspiracy narratives to cause confusion, inverting correct and incorrect information and destabilizing the reputation of democratic institutions, including the government and political parties, academia and science, journalists and news sources, as well as transnational organizations such as WHO, WTO, or NATO. Given that conspiracy narratives are often based on the assumption that certain persons or institutions operate in the dark and hide information or their true intentions from “the people,” these narratives can be easily discursively connected with the anti-elite, anti-establishment antagonistic stance of the New Right and its political arm of right-wing populism, based on a very similar dichotomy of “good” vs. “evil,” or “us” vs. “them” (Butter 2020). As we have seen in our analysis, the two actors discussed in this report pursue these metapolitical strategies to a lesser or greater extent.

Suzuki’s main narrative—which revolves around blaming the United States and the West for prolonging the war while avoiding direct criticism of the Japanese government’s alignment with the United States—highlights his unique approach to utilizing pro-Kremlin narratives. Instead of openly criticizing the Japanese government, Suzuki emphasizes the peaceful nature of the Japanese nation and the importance of pursuing a ceasefire as a priority over providing financial and military support to Ukraine. This approach allows him to advocate for better relations with Russia, driven by his political agenda related to the negotiation over the Northern Territories, all without directly challenging Japan’s alignment with the United States. He also highlights the economic benefits for Japan, particularly in terms of securing natural resources due to Japan’s resource deficiency.

The objectives of Issuikai align with the party’s anti-American stance and the desire to foster relations with neighboring Asian countries, including Russia. It leverages the war in Ukraine to criticize the Japanese government and highlight what it views as the detrimental influence of the United States, with which Japan is aligned. Ukraine serves as an example of the consequences they associate with nations governed by the United States, and it serves as a case study to highlight biased perceptions of countries receiving Western support. Issuikai employs various tactics to achieve these objectives. It attributes detrimental shifts in Japanese society to external influences and the adoption of values of Western nations, which it views as a minority in the global landscape. Issuikai inverted a two-thirds majority that voted for the UN resolution to condemn Russia to two-thirds of the world population residing in the countries that opposed or remained neutral. Moreover, the social media content of Issuikai presents the Ukrainian government as entirely corrupt and incompetent and frames the war as an ethnic conflict or portrays Ukraine as a threat to Asia to influence public sentiment against any alignment with or support for Ukraine. Its narrative involves historical revisionist framing and a biased perspective to strengthen the emotional connection between Japanese and Russian audiences. This perspective reinforces its narrative of Russia as a more favorable partner for Japan compared to the United States. Furthermore, the oversimplification and distortion of historical facts, as seen in Suzuki’s comparison between Japan and Ukraine and Issuikai’s misrepresentation of Russia’s role in World War II, serve as a stark example of the dangers inherent in propaganda. This manipulation of information is a potent tool for shaping public opinion, allowing for the creation of a narrative that deviates from the nuanced reality of historical events.

In summary, as the analysis of the discourse shows, Russian propaganda is versatile and can be employed by various political actors, regardless of their political leanings, to serve their specific objectives. Russian propagandists can tailor their anti-Western and authoritarian narratives to potentially fit with the agendas of potential allies in their propaganda warfare operations. Whether the goal is to create doubt about a government’s foreign policies, divert public attention to local issues, or exploit concerns about economic decline or globalization, Russian propaganda seeks to sow discord and division.

Adamczyk, Roman, and Sasha Morinière. 2021. “The Impact of the Russia-Ukraine War on French-Speaking Fringe Communities Online.” ISD. https://www.isdglobal.org/isd-publications/the-impact-of-the-russia-ukraine-war-on-french-speaking-fringe-communities-online/.

Alessandro. 2023. “Study: The Most Effective Propaganda-Spreading Embassy Is the Russian One in Sofia.” Insight News Media, April 1. https://insightnews.media/study-the-most-effective-propaganda-spreading-embassy-is-the-russian-one-in-sofia/.

“Amending Japan’s Pacifist Constitution.” 2018. Institute for Security and Development Policy. Accessed December 21, 2022. https://isdp.eu/publication/amending-japans-pacifist-constitution/.

Andreae, Jonas. 2022. “The Information War of RT DE.” In RT in Europe and Beyond, edited by Anton Shekhovtsov, 68–78. Vienna: Centre for Democratic Integrity.

Baker, Paul. 2010. “Representations of Islam in British Broadsheet and Tabloid Newspapers 1999–2005.” Journal of Language and Politics 9(2): 310–38. https://doi.org/10.1075/jlp.9.2.07bak.

Balint, Kata. 2022. “In the Midst of an Election, Hungarian State-Linked Media Pushes pro-Kremlin Narratives Surrounding the Invasion of Ukraine.” ISD (blog), March 24. https://www.isdglobal.org/digital_dispatches/in-the-midst-of-an-election-hungarian-state-linked-media-pushes-pro-kremlin-narratives-surrounding-the-invasion-of-ukraine/.

Balint, Kata, Francesca Arcostanzo, Jordan Wildon, and Kevin Reyes. 2022. “RT Articles Are Finding Their Way to European Audiences – but How?” ISD (blog), July 20. https://www.isdglobal.org/digital_dispatches/rt-articles-are-finding-their-way-to-european-audiences-but-how/.

Brandt, Jessica, and Valerie Wirtschafter. 2022. “Working the Western Hemisphere.” Brookings, December. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/working-the-western-hemisphere/.

Brown, James D. J. 2019a. “Abe’s Russia Policy: All Cultivation and No Fruit.” Asia Policy 14(1): 148–55.

———. 2019b. “Abe’s Underperforming Russia Policy Faces Growing Political Backlash.” East Asia Forum, March 13. https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2019/03/13/abes-underperforming-russia-policy-faces-growing-political-backlash/.

———. 2021. “Russian Strategic Communications toward Japan: A More Benign Model of Influence?” Asian Perspective 45(3): 559–86. https://doi.org/10.1353/apr.2021.0027.

———. 2023. “Japan’s Aging Pro-Russia Lobby Is on Borrowed Time.” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, October 12. https://carnegieendowment.org/politika/90763.

Butter, Michael. 2020. The Nature of Conspiracy Theories. Cambridge: Polity.

Clark, Mitchell. 2022. “YouTube Is Now Blocking Russian State-Funded Media Worldwide.” The Verge, March 11. https://www.theverge.com/2022/3/11/22972911/youtube-rt-russian-sputnik-block-state-media-globally.

Council of the EU. 2022. “EU Imposes Sanctions on State-Owned Outlets RT/Russia Today and Sputnik’s Broadcasting in the EU.” consilium.europa.eu, March 2. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2022/03/02/eu-imposes-sanctions-on-state-owned-outlets-rt-russia-today-and-sputnik-s-broadcasting-in-the-eu/.

“Deutsche Wahrheit: A pro-Kremlin Effort to Spread Disinformation about Ukrainian Refugees.” 2022. ISD (blog), December 1. https://www.isdglobal.org/digital_dispatches/deutsche-wahrheit-a-pro-kremlin-effort-to-spread-disinformation-about-ukrainian-refugees/.

Ferguson, Joseph. 2008. Japanese-Russian Relations, 1907–2007. Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/Japanese-Russian-Relations-19072007/Ferguson/p/book/9780415674478.

Fuchs, Tamara, and Fabian Schäfer. 2020. “Normalizing Misogyny: Hate Speech and Verbal Abuse of Female Politicians on Japanese Twitter.” Japan Forum, 1–27. https://doi.org/10/gmdktn.

“GEC Special Report: Russia’s Pillars of Disinformation and Propaganda.” 2020. Global Engagement Center. https://www.state.gov/russias-pillars-of-disinformation-and-propaganda-report/.

“General Results of the Census. National Composition of Population.” December 17, 2011. https://web.archive.org/web/20111217151026/http://2001.ukrcensus.gov.ua/eng/results/general/nationality/.

Gomza, Ivan. 2022. “Too Much Ado About Ukrainian Nationalists: The Azov Movement and the War in Ukraine.” Krytyka, April. https://krytyka.com/en/articles/too-much-ado-about-ukrainian-nationalists-the-azov-movement-and-the-war-in-ukraine.

Hall, Jeffrey James. 2018. “Japan’s Right-Wing YouTubers: Finding a Niche in an Environment of Increased Censorship.” Asia Review 8(1): 315–50. https://doi.org/10.24987/SNUACAR.2018.08.8.1.315.

Heinrich, Philipp, Christoph Adrian, Olena Kalashnikova, Fabian Schäfer, and Stefan Evert. 2018. “A Transnational Analysis of News and Tweets about Nuclear Phase-Out in the Aftermath of the Fukushima Incident.” In Proceedings of the LREC 2018 “Workshop on Computational Impact Detection from Text Data,” 8–16. Miyazaki, JP: Paris: ELRA.

Higgins, Andrew. 2019. “Putin Quashes Japanese Hopes of End to Island Dispute.” The New York Times, January 22. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/01/22/world/europe/kuril-islands-putin-abe.html.

Hodgson, Jayden. 2021. “Reenvisioning Russian Propaganda: Media Decentralization and the Use of Social Networks as a Means to Government Continuity.” Open Political Science 4(1): 238–57. https://doi.org/10.1515/openps-2021-0022.

Iriarte, Daniel. 2022. “RT En Español: How Russian Disinformation Targets 500 Million Spanish Speakers.” In RT in Europe and Beyond, edited by Anton Shekhovtsov, 14–25. Vienna: Centre for Democratic Integrity.

Issuikai (@issuikai_jp). 2023. 弊会木村代表が参加した「ヤルタ国際フォーラム」の様子が、『スプートニク日本』にて紹介された。「クリミア友人会議」のメンバーとして参加し、「クリミア住民の自己決定権の尊重、経済制裁への反対」を訴えたことが報じられている。 [The appearance of our representative, Kimura, at the “Yalta International Forum” has been introduced in “Sputnik Japan.” It is reported that he participated as a member of the “Crimea Friendship Conference” and advocated for “Respect for the self-determination rights of Crimean residents” and “opposition to economic sanctions.”].’ X (Formerly Twitter), October 28. https://twitter.com/issuikai_jp/status/1718295733818867889.

Ito, Masaaki 伊藤昌亮. 2019. ネット右派の歴史社会学 アンダーグラウンド平成史1990–2000年代 [Historical Sociology of the Net-Right Underground Heisei History of the 1990s–2000s]. Tokyo: Seikyūsha.

Iwashita, Akihiro. 2019. “Abe’s Foreign Policy Fiasco on the Northern Territories Issue: Breaking with the Past and the National Movement.” Eurasia Border Review 10(1): 111–33.

———. 2020. “Bested by Russia: Abe’s Failed Northern Territories Negotiations.” Wilson Center. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/kennan-cable-no-60-bested-russia-abes-failed-northern-territories-negotiations.

Kalashnikova, Olena, and Fabian Schäfer. 2020. “A Corpus-Linguistic Analysis of Media Discourses on Nuclear Phase-out in Japan, 2011–2014.” Journal of International and Advanced Japanese Studies 12: 137–53.

Kalashnikova, Olena. 2024. “Pro-Russian Propaganda in Hatoyama’s Tweets.” Digital Japan Lab (blog), March 27. https://www.digital-japan.org/2024/03/27/blog-pro-russian-propaganda-in-hatoyamas-tweets/.

Kanamori, Takayuki 金森崇之, and Hatta Kosuke八田浩輔. 2022. “ロシアのプロパガンダ、誰が拡散? SNS分析でみえた情報戦の姿 [Who Is Spreading Russian Propaganda? The Shape of Information Warfare Seen through Social Media Analysis].” 毎日新聞 [Mainichi Shimbun], 5 May. https://mainichi.jp/articles/20220504/k00/00m/030/248000c.

Kazakov, Vitaly. 2022. “Ambitious Goals and Modest Results: RT UK and Its Coverage of the 2019 British General Elections.” In RT in Europe and Beyond, edited by Anton Shekhovtsov, 80–97. Vienna: Centre for Democratic Integrity.

K.C. 2010. “How Le Pen Honours Japan’s War Dead: Correspondent’s Diary, Day Three.” The Economist, August 15. https://www.economist.com/banyan/2010/08/15/how-le-pen-honours-japans-war-dead-correspondents-diary-day-three.

Kling, Julia, Florian Toepfl, Neil Thurman, and Richard Fletcher. 2022. “Mapping the Website and Mobile App Audiences of Russia’s Foreign Communication Outlets, RT and Sputnik, across 21 Countries.” Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review, December. https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-110.

Kravets, Daria, Anna Ryzhova, Florian Toepfl, and Arista Beseler. 2023. “Different Platforms, Different Plots? The Kremlin-Controlled Search Engine Yandex as a Resource for Russia’s Informational Influence in Belarus during the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Journalism 24(12): 2762–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/14648849231157845.

Kyodo. 2023. “Former PM Mori Urges against Excessive Support for Ukraine.” The Japan Times, January 25. https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2023/01/25/national/mori-ukraine-support/.

Kyodo News. 2022. “Ex-Japan PM Harsh on Zelenskyy over War in Ukraine,” November 19. https://english.kyodonews.net/news/2022/11/d84dcf59dc65-refiling-ex-japan-pm-harsh-on-zelenskyy-over-war-in-ukraine.html.

———. 2023. “Japan Lawmaker Who Made Unannounced Russia Trip Removed from Party,” October 10. https://english.kyodonews.net/news/2023/10/9a53ba1020fa-japan-innovation-party-removes-lawmaker-over-unannounced-russia-trip.html.

Mainichi Shimbun 毎日新聞. 2022. “ウクライナ侵攻 安倍元首相、シンポで発言 「プーチン氏、信長と同じ」 [Ex-PM Abe Compares Russia’s Putin to 16th Century Japanese Warlord Oda Nobunaga].” April 23. https://mainichi.jp/articles/20220423/ddm/005/030/127000c.

“Mapping Militant Organizations. ‘Azov Movement.’” 2022. Stanford University, August. https://cisac.fsi.stanford.edu/mappingmilitants/profiles/azov-battalion.

Messieh, Nancy. 2023. “Narrative Warfare.” Atlantic Council (blog), February 22. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/report/narrative-warfare/.

MID. 2023. “Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov’s Interview with Channel One’s Bolshaya Igra (Great Game) Political Talk Show.” MID, December 18, https://mid.ru/ru/foreign_policy/news/1921650/?lang=en.

Moldovanov, Ruslan. 2019. “Why does Zhirinovsky gather European nationalists in the State Duma? (Zachem Zhirinovskiy sobirayet yevropeyskikh natsionalistov v Gosdume).” Riddle Russia, August 2. https://ridl.io/ru/zachem-zhirinovskij-sobiraet-evropejskih-nacionalistov-v-gosdume/.

Mulgan, Aurelia George. 2010. “Japan’s Bureaucracy Strikes Back.” East Asia Forum (blog), March 26. https://eastasiaforum.org/2010/03/26/japans-bureaucracy-strikes-back/.

NHK. 2023. “ロシア外務次官 ‘平和条約交渉など 日本と対話の見通しない’” [Russian Deputy Foreign Minister: ‘There is no prospect of dialogue with Japan such as peace treaty negotiations’]”, December 17. https://www3.nhk.or.jp/news/html/20231217/k10014290381000.html.

Nojima, Jun 野島淳. 2022. “「でっち上げの主張による不当攻撃」 G7声明、制裁の詳細は記さず:朝日新聞デジタル [‘Unjust Attack Based on Fabricated Claims’ G7 Statement, No Details of Sanctions Mentioned].” 朝日新聞デジタル [Asahi Shimbun Digital], February 25. https://www.asahi.com/articles/ASQ2T12N8Q2SUHBI07J.html?iref=ogimage_rek.

Oates, Sarah. 2016. “Russian Media in the Digital Age: Propaganda Rewired.” Russian Politics 1(4): 398–417. https://doi.org/10.1163/2451-8921-00104004.

O’Connor, Ciarán. 2022. “#Propaganda: Russia State-Controlled Media Flood TikTok With Ukraine Disinformation.” ISD (blog), March 2. https://www.isdglobal.org/digital_dispatches/propaganda-russia-state-controlled-media-flood-tiktok-with-ukraine-disinformation/.

“On Facebook, Content Denying Russian Atrocities in Bucha Is More Popular than the Truth.” 2022. ISD (blog), April 20. https://www.isdglobal.org/digital_dispatches/on-facebook-content-denying-russian-atrocities-in-bucha-is-more-popular-than-the-truth/.

Orttung, Robert W., and Elizabeth Nelson. 2019. “Russia Today’s Strategy and Effectiveness on YouTube.” Post-Soviet Affairs 35(2): 77–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/1060586X.2018.1531650.

Paul, Christopher, and Miriam Matthews. 2016. “The Russian ‘Firehose of Falsehood’ Propaganda Model. Why It Might Work and Options to Counter It.” RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/perspectives/PE198.html.

Peters, Jay. 2022. “Facebook Blocks RT and Sputnik Pages in the EU.” The Verge, March 1. https://www.theverge.com/2022/2/28/22955542/facebook-meta-blocks-rt-sputnik-eu-instagram.

Ponomarenko, Illia. 2021. “Ukraine Conducts First-Ever Drone Strike in Donbas.” KyivPost, October 27. https://www.kyivpost.com/post/10268.

“Prime Minister Abe and President Putin.” 2016. The Government of Japan. https://www.japan.go.jp/tomodachi/2016/japan_and_russia_edition_2016/moments_of_prime_minister_abe.html.

Rankin, Jennifer. 2022. “Orbán Treads Fine Line as Hungarian Opinion Swings against Russia.” The Guardian, 17 March. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/mar/17/orban-treads-fine-line-as-hungarian-opinion-swings-against-russia.

“Reception on the Occasion of Russia Day Held at the Russian Embassy in Tokyo.” 2022. The Embassy of the Russian Federation in Japan, June 9. https://tokyo.mid.ru/en/novosti_posolstva/reception_on_the_occasion_of_russia_day_held_at_the_russian_embassy_in_tokyo/.

RFE/RL. 2017. “Ukraine Rejects Claims It Supplied Rocket Engines To North Korea.” August 22. https://www.rferl.org/a/ukraine-rejects-claims-it-supplied-rocket-engines-north-korea/28691003.html.

———. 2022. “Russian Government Orders Media Outlets to Delete Stories Referring To ‘Invasion’ Or ‘Assault’ On Ukraine.” February 26. https://www.rferl.org/a/roskomnadzor-russia-delete-stories-invasion/31724838.html.

Shekhovtsov, Anton. 2019. “Foreign Observation of the Illegitimate Elections in South Ossetia and Abkhazia in 2019.” European Platform for Democratic Elections. https://www.academia.edu/41212582/Foreign_Observation_of_the_Illegitimate_Elections_in_South_Ossetia_and_Abkhazia_in_2019.

Shūkan Bunshun 週刊文春. 2022. “鈴木貴子が宗男から受け継いだ外務省攻撃とカネ [Money and Attacks on the Ministry of Foreign Affairs that Takako Suzuki inherited from Muneo].” March 16. https://bunshun.jp/denshiban/articles/b2673.

Smirnova, Julia, and Francesca Arcostanzo. 2022. “German-Language Disinformation about the Russian Invasion of Ukraine on Facebook.” ISD (blog), March 1. https://www.isdglobal.org/digital_dispatches/german-language-disinformation-about-the-russian-invasion-of-ukraine-on-facebook/.

Smirnova, Julia, Paula Matlach, and Francesca Arcostanzo. 2022. “Support from the Conspiracy Corner: German-Language Disinformation about the Russian Invasion of Ukraine on Telegram.” ISD (blog), March 4. https://www.isdglobal.org/digital_dispatches/support-from-the-conspiracy-corner-german-language-disinformation-about-the-russian-invasion-of-ukraine-on-telegram/.

Spahn, Susanne. 2021. “Russian Media in Germany. How Russian Information Warfare and Disinformation Have Affected Germany.” 766. Berlin: ISPSW Institut für Strategie- Politik- Sicherheits- und Wirtschaftsberatung. https://www.ispsw.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/765_Schneider.pdf.

Suzuki, Muneo. 2018. Political Life (Seiji Jinsei). Tokyo: Chūōkōron Shinsha.

TASS. 2018. “Синдзо Абэ: президент Путин мне дорог как партнер, с ним можно поговорить по душам [Shinzo Abe: President Putin is dear to me as a partner, I can have a heart-to-heart talk with him].” November 25. https://tass.ru/interviews/5826060.

———. 2023. “Japanese MP on Visit to Moscow Emphasizes Importance of Russian-Japanese Dialogue.” October 3. https://tass.com/world/1684033.

The Kyiv Independent. 2022. “Zelenskyy’s Full Speech at Munich Security Conference.” February 19. https://kyivindependent.com/zelenskys-full-speech-at-munich-security-conference/.

Thomas, Elise. 2022. “Russia Today Digs Deep to Stay on YouTube.” ISD (blog), July 5. https://www.isdglobal.org/digital_dispatches/russia-today-digs-deep-to-stay-on-youtube/.

Thompson, Jay Daniel, and Timothy Graham. 2022. “Russian Government Accounts Are Using a Twitter Loophole to Spread Disinformation.” The Conversation, March 15. http://theconversation.com/russian-government-accounts-are-using-a-twitter-loophole-to-spread-disinformation-178001.

Toepfl, Florian, Daria Kravets, Anna Ryzhova, and Arista Beseler. 2022. “Who Are the Plotters behind the Pandemic? Comparing Covid-19 Conspiracy Theories in Google Search Results across Five Key Target Countries of Russia’s Foreign Communication.” Information, Communication & Society 26(10): 2033–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2022.2065213.

Toepfl, Florian, Anna Ryzhova, Daria Kravets, and Arista Beseler. 2023. “Googling in Russian Abroad: How Kremlin-Affiliated Websites Contribute to the Visibility of COVID-19 Conspiracy Theories in Search Results.” International Journal of Communication 17(0): 21.

“Transcript of Pelosi Opening Remarks at Bilateral Meeting with Vice President of the Legislative Yuan of Taiwan Tsai Chi-Chang.” 2022. pelosi.house.gov, August 2. http://pelosi.house.gov/news/press-releases/transcript-of-pelosi-opening-remarks-at-bilateral-meeting-with-vice-president-of.

Umland, Andreas. 2019. “Irregular Militias and Radical Nationalism in Post-Euromaydan Ukraine: The Prehistory and Emergence of the ‘Azov’ Battalion in 2014.” Terrorism and Political Violence 31(1): 105–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2018.1555974.

“Vladimir Dzhabarov Meets with Chair of the Japanese Civic and Political Organisation Mitsuhiro Kimura.” 2023. Federation Council of the Federal Assembly of the Russian Federation, October 26. http://council.gov.ru/en/events/news/149403/.

Yablokov, Ilya. 2021. Russia Today and Conspiracy Theories. London: Routledge.

Yatsyk, Alexandra. 2022. “The COVID-19 Crisis in Europe: A Story Told by RT.” In RT in Europe and Beyond, edited by Anton Shekhovtsov, 108–28. Vienna: Centre for Democratic Integrity.

- As of August 15, 2023.

- Twitter was rebranded to X in July 2023. However, for the purposes of this study, we will continue to use the previous name due to the collected data timeframe.

- Channel One

- Not accessible from the EU any longer.

- Global Research is operated by The Centre for Research on Globalization. The organization, self-described as an “independent research and media organization” based in Canada, is also a registered non-profit entity.

- Mori criticized President Zelenskyy on multiple occasions, saying, “I don’t quite understand why only President Putin is criticized while Mr. Zelenskyy isn’t taken to task at all. Mr. Zelenskyy has made many Ukrainian people suffer” (Kyodo News 2022) or exhibiting allegiance to Russia and criticizing the Japanese government for supporting Ukraine (The Japan Times 2023).

- We have excluded our analysis of Hatoyama’s pro-Russian stance from this article based on our decision to provide a more in-depth focus on actors from the right ideological spectrum. We have published the results of an analysis of Hatoyama’s activities in a blog post on pro-Russian propaganda in Yukio Hatoyama’s tweets (cf. Kalashnikova 2024).

- Additionally, he uses Twitter to share links to his Ameba Blog. Since there is no information on Facebook about the total number of posts, we provide additional information about his other accounts. The posts are dedicated to multiple events and Suzuki gives his thoughts on what happened during the day or recently. The war in Ukraine is one of the topics he frequently discusses.

- Facebook posts were collected manually; Twitter posts were collected automatically using the public API.

- As of October 16, 2023.

- A freeware corpus analysis toolkit for concordances and text analysis developed by Laurence Anthony.

- Frequent keywords, namely terms that occur more often in the corpus, are measured towards the reference corpus to reveal the “aboutness” of the corpus (Baker 2010). The construction of the reference corpus depended on the research objectives. In this study, a sample of random tweets collected in May 2023, comprising 11,304,852 tokens and 356,363 types, served as the reference corpus.

- Linguistic patterns were discerned through collocation analysis to reveal connotations of the keywords related to the war in Ukraine, including the terms “Ukraine,” “Russia,” “Putin,” and “Zelenskyy.” In corpus linguistics, “collocates” are words that tend to appear together or in close proximity to the “search” word, typically within a window of 3-5 words. Analyzing co-occurrence patterns of collocates unveils meaningful associations and helps identify common ideas linked to the search word, thereby revealing ideological assumptions within the given discourse.

- The posts were selected if containing keywords: ’ウクライナ,’ ’ゼレンスキー,’ ’ロシア,’ ’プーチン,’ ’キエフ,’ ’キーウ’ (‘Ukraine,’ ‘Zelenskyy,’ ‘Russia,’ ‘Putin,’ ‘Kiev,’ ‘Kyiv’), and words related to Russia, such as ’中露,’ ’日露,’ ’露軍’ (‘China-Russia,’ ‘Russia-Japan,’ ‘Russian military’).

- Following a full-scale invasion, Japan imposed comprehensive sanctions on Russia, and Russia added Japan to its list of “unfriendly nations” in response, resulting in a further deterioration of diplomatic relations between the two nations. Deputy Foreign Minister Rudenko stated that “full-fledged bilateral dialogue is impossible” (NHK 2023) and soon after that, on December 18th, 2023, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Sergei Lavrov, said in an interview that Russia does not have territorial disputes with any country, including Japan (MID 2023). For a long time, the absence of a formal peace treaty between Japan and Russia following World War II and the territorial dispute about the Kuril Islands, known as the Northern Territories in Japan, linked to it constituted a central challenge in their bilateral relations. Competing claims in the Sea of Japan for fishing rights and access to natural resources contribute to the complexity of the relations. Additionally, the presence and policies of the United States in the region influence their relations, especially in security matters. The normalization of Japan-Russia relations was revived during the second term of Shinzō Abe. Consequently, following the annexation of Crimea in 2014, Japan refrained from imposing tough sanctions on Russia, and Abe continued to build a trusting relationship with President Putin (Brown 2019c; Iwashita 2019). Overall Putin and Abe held 15 summit meetings (‘Prime Minister Abe and President Putin’ 2016) and 27 meetings in total between 2012-2020 (Iwashita 2020), emphasizing their amicable relations (Higgins 2019; TASS 2018), but these exchanges did not yield visible results (Iwashita 2019). Moreover, even after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Abe downplayed the severity of the situation by refraining from condemning Putin and showing support (Mainichi Shimbun 2022).

- Satō aligns with pro-Russian narratives regarding the justification of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, saying: “President Zelenskiy of Ukraine also bears a large responsibility for this situation” (Nojima 2022).

- Pacifism is a political and social principle that is rooted in the Japanese Constitution and emphasizes the rejection of war and military aggression as a means of resolving international disputes.

- http://kremlin.ru/events/president/news/70330

- ロシアの特別軍事行動はウクライナがその原因を作ったわけですからウクライナが停戦に応じるべきです。

- 円安が進み、諸物価が上がり、日本経済はじめ世界経済がどうなるのか心配である。先ずはウクライナ紛争を停戦させることが一番である。ウクライナが8000平方の土地を取り戻したと言っても戦況に大きな変化はない。自前で戦えないなら平和的解決を模索すべきである。77年前、日本は一部陸軍の強硬派により「一億総玉砕」「竹槍で米国と戦う」と言い結果はどうなったか。日本の二の舞いをウクライナにやらせてはならない。77年前、半年前に降伏していれば、東京大空襲も沖縄戦も、広島、長崎に核が落とされることはなかった。勇ましいことを言う前に、沈着冷静に先を見据えることが大事である。日本の果たすべきことはあると考えるものだが。

- Suzuki claims in his posts that the attack happened on October 23, 2022.

- The attack was targeting a D-30 howitzer used by Russian-sponsored militants and placed too close to the front line according to the Minsk agreement. The attack was initiated in response to the shelling that resulted in the death of a Ukrainian soldier in the region and the injury of another (Ponomarenko 2021).