Abstract: Disaster risk reduction experts and organizations across Tokyo are using the 100th anniversary of the Great Kantō Earthquake as an opportunity to not only remember the disaster, but also to urge residents to rethink their disaster preparedness in anticipation of the next big earthquake. At Yokoamichō Park, the Tokyo Metropolitan Memorial Association worked with local primary schools in Sumida ward to bring to life precious records written by children who experienced the 1923 earthquake and fires. From September 2023, a multi-media compilation of children’s accounts will be featured in a new exhibition at the Great Kantō Earthquake Memorial Museum.

Keywords: Great Kantō Earthquake Memorial Museum, Tokyo, Honjo, Sumida ward, primary schools, children’s essays and drawings, anniversary events

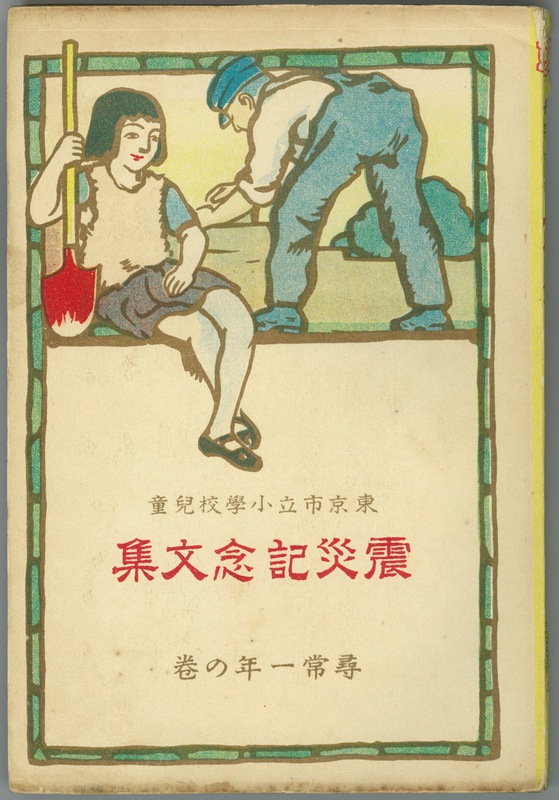

One year after the Great Kantō Earthquake, the City of Tokyo published a seven-volume collection of essays to mark the anniversary. The collection, titled Tōkyō shiritsu shōgakkō jidō: Shinsai kinen bunshū, attracted significant attention.

Figure 1: Tōkyō shiritsu shōgakkō jidō: Shinsai kinen bunshū, volume 1. Photograph by author.

A front-page advertisement printed in the Yomiuri Shinbun on September 1, 1924 was stamped with five characters denoting an imperial inspection by the emperor (shitenran tairan) and also contained a laudatory endorsement from the Mayor of Tokyo. The advertisement embodied the high hopes and expectations that many held for these commemorative essays. Catchlines described the volumes as “an unprecedented publication commemorating the earthquake” and “a precious record for future generations.” The publicity and praise were remarkable, especially given the fact that the authors were children. Teachers went to considerable lengths to document and collate children’s experiences of the earthquake and fires at the time, and also to preserve their essays for posterity. Despite their earnest efforts, however, the Shinsai kinen bunshū volumes sat on the shelves of libraries and archives overlooked for decades. Today, the contents of the volumes are attracting renewed attention in Japan as part of projects to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Great Kantō Earthquake.

Earthquake Children and Their Essays in the Archives

I first discovered the Shinsai kinen bunshū collection early in my research as a Masters student at the University of Melbourne. I found a copy of volume three for sale on the Nihon no furuhonya website and ordered it for the Baillieu Library’s East Asian Collection. The volume contained 378 essays and two drawings by grade three children representing primary schools from all of Tokyo’s fifteen administrative wards. From this volume alone, I learned about children’s firsthand experiences of the earthquake and fires, the search for safe refuge, and the wild rumors that spread panic across the city. I also gained insights into children’s daily life in the weeks and months following the disaster. The content of the essays was fascinating, and I quickly recognized that this was a rare and valuable collection. But I was left with many unanswered questions about their compilation, production, and use. When, how and why did children write these essays? Where did children get pencils and paper and crayons from, given the fact that 117 out of Tokyo’s 196 schools were destroyed by the earthquake and fires? What role did teachers play? Why were they published and how were they used for commemoration? Did any original essays survive? Despite exhaustive searches of the archives as a postgraduate and meetings with archivists at places such as the Tokyo Metropolitan Archives, the National Diet Library, and the Great Kantō Earthquake Memorial Museum (Fukkō kinenkan), I was unable to find any information about the genesis and production of the children’s essays.

Ten years later, I decided to renew my search for the original children’s essays and returned to the Great Kantō Earthquake Memorial Museum. This time I had success. Staff member Yamaguchi Yoshimasa greeted me with a large plastic container filled to the brim with original essays written by children. None of the items had been catalogued. He spilled the contents on to a table and I began to photograph. Most of the essays were written in pencil on Japanese notepaper (genko yōshi). Some essays were written in katakana by first grade students, while older children wrote in a mix of hiragana and kanji. Schools grouped the essays together according to year level. The square grids of notepaper were folded and preserved in simple booklets bound with string. Some covers were decorated with children’s color drawings, others had a title written in black ink such as “Memories of September 1 (Kugatsu tsuitachi no omoide)”.

One slim booklet I photographed contained essays written by children from Midori Primary School.

Figure 2: Shinsai kinen bunshū: Unpublished collection of essays by Midori Primary School. Photograph by author, courtesy of the Great Kantō Earthquake Memorial Museum Collection.

Fire destroyed eighteen of the nineteen primary schools in Honjo ward, including Midori. According to the school’s website, 295 children and 3 staff died. When classes resumed on 3 October 1923, only 37 children gathered at the ruined site. In the weeks and months ahead, children from Midori began to write essays using pencils and notebooks donated from schools around Japan. One essay that caught my eye was written by a nine-year old girl called Iwata Tsune. Her short essay is titled “The fires (Kuwaji).”

Figure 3: Original essay by Iwata Tsune. Photograph by author, courtesy of the Great Kantō Earthquake Memorial Museum Collection.

In simple katakana script, the first-grade girl described fleeing toward Tsukushima in the south of Tokyo. The streets were crowded with people carrying belongings and pulling carts. After the fires, she walked through the ruins of Honjo in search of her home. “There were many dead bodies,” Iwata wrote. “They were in the river too. And inside the train. When we arrived home there was a pile of burned red bricks and nothing else” (quoted in Borland, 2020, 70). Iwata’s original essay contains rare and valuable evidence: red pen marks indicate that her teacher corrected a spelling error and inserted punctuation. Not only is Iwata’s original essay preserved in the Earthquake Memorial Museum, it was also chosen as one of two essays representing first grade children from Midori Primary School and published in volume one of the Shinsai kinen bunshū.

Figure 4: Iwata Tsune’s essay. Photograph by author.

A side-by-side comparison of the two essays reveals that Iwata’s essay was published word-for-word.

In schools all across Tokyo, children wrote essays not as a form of catharsis, but as exercises in their regular curriculum or writing class. Teachers went to great lengths to procure pencils and notebooks. There is no evidence, however, to suggest that writing essays about the earthquake disaster was directed or initiated by central school administrators. Neither is there any evidence to suggest that teachers intended to eventually exhibit or publish the essays. Rather, essay writing was a relatively simple activity that children could continue as part of their regular education in this otherwise highly irregular and unstable environment. Essay writing (tsuzurikata) already comprised a fundamental component of Japanese language classes (kokugo) whereby children wrote about their experiences and observations of daily life, therefore it was logical for children to write about their recent experiences of the earthquake (Borland, 2020, 121-122). Between October 1923 and February 1924, school children wrote about every aspect of the disaster and daily life in the aftermath. Children recalled where they were and what they were doing when the earthquake struck. They described what it was like when the fires started, fleeing through crowded streets searching for safe refuge. They recalled being hungry, thirsty, hot, and afraid. Many simply described Tokyo as “hell on earth” (see Borland, 2020, chapter 2). But children also wrote about the things that made them feel happy and grateful, such as receiving an onigiri rice ball after days without food, or returning to school and meeting their friends again. Their essays contained messages of hope, recovery, and gratitude.

A poem written by third grade boy Matano Yasunosuke conveys powerful emotions that were no doubt shared by many survivors. In just a few sentences the student from Imakawa Primary School in Kanda encapsulated both the tragic losses he suffered as a result of the earthquake and fires, as well as his hopes and determination to rebuild Tokyo and help better prepare Japan for future earthquakes (Tōkyōshi gakumuka, vol. 3, 35-36):

“Jishin (Earthquake)”

You took away my friends

And you burned down our schools.

Who do you think you are down there?

Everything is your fault you know.

Listen up, earthquake! Listen up!

We are going to strengthen our bodies and sharpen our minds wholeheartedly from now on.

When we grow up

we will build houses with strong foundations.

Next time,

no matter how strong you shake

our pillars will not yield an inch.

As sure as the hands on the clock keep ticking,

With time, we will get our revenge.

Teachers genuinely wanted to learn and understand how the disaster affected children, and these essays contained valuable information. But it was not only teachers who recognized the value of children’s essays. Government and education officials, media, and relief organizations also recognized the important role that children and their essays could play in a society recovering from disaster. Children represented the future of Tokyo as the next generation and their candid voices were used for a variety of commemorative purposes.

I eventually found the missing link explaining the municipal government’s decision to publish the children’s essays. As I continued my research on the earthquake, more and more archives were digitized and I uncovered a huge amount of material about Tokyo’s earthquake children. Newspapers were especially useful sources. From September 1923 onwards, newspapers published stories about school children, lost children, orphaned children, homeless children and newborn babies on an almost daily basis. They also published stories and pictures by children. In the aftermath of the Great Kantō Earthquake, children were seen and their voices were heard. Their essays, letters, poems, songs, postcards and drawings made frequent appearances in the press, and as I soon discovered, figured prominently in public exhibitions as well.

On 1 March 1924, the Tōkyō asahi shinbun published an article about a week-long exhibition in Ueno. The exhibition, sponsored by the City of Tokyo, featured over 1,300 items made by children including essays, drawings, craft and models. The headline read, “This exhibition will move you to tears” (Borland, 2020, 131). Soon after the exhibition, Mayor Nagata Hidejirō announced that the municipal government had decided to publish the essays to remind future generations about the 1923 earthquake. On 18 August 1924, Sasaki Kichisaburō, Director of Tokyo’s Education Department wrote a message which was printed in the foreword of the Shinsai kinen bunshū (Tōkyōshi gakumuka, 1924). “We want to commemorate this unprecedented disaster forever and offer this collection for the education of the people for a long time to come. If a memorial museum were to be built in the city,” he concluded, “this collection would be one of the most valuable memorial items on display.”

Earthquake Children’s Voices Resonate Today

To mark the 100th anniversary of the 1923 disaster, the Tokyo Metropolitan Memorial Association is refurbishing numerous exhibits at the Great Kantō Earthquake Memorial Museum. By digitizing various archives and employing audio-visual technology, they are bringing to life items from their archives in a quest to share the history of the 1923 earthquake in an easier to understand, interactive format, and also to promote disaster awareness. When the renovated exhibition opens in time for the September 1 anniversary this year, visitors will be able to explore four new installations: an interactive map of Tokyo embedded with five thousand digitized photographs; videos of two stories dealing with the earthquake which have been animated; a virtual reality tour of Tokyo based on a 3-D reconstruction model of the capital; and, an archive of essays selected from the seven-volume Shinsai kinen bunshū, preserved on DVD.

Figure 5: Poster illustrating new exhibitions in the Great Kantō Earthquake Memorial Museum to mark the 100th anniversary. Photograph by author, courtesy of the Great Kantō Earthquake Memorial Museum Collection.

In June 2023, I met with Uesugi Toshikazu, executive director of the Tokyo Metropolitan Memorial Association, and his colleague Takada Ken’ichi to learn more about the Association’s 100-year anniversary projects. For decades, Takada told me, the Shinsai kinen bunshū volumes sat in the collection of the Great Kantō Earthquake Memorial Museum, occasionally exhibited in a glass case. Yet even when they were on display, the precious contents remained unknown to visitors. He explained that as a small museum with limited space available to exhibit items from their extensive collection, they needed to find a creative solution to share the children’s essays. In April 2022, the Museum decided to bring the contents of the Shinsai kinen bunshū to life so that people today could “feel the real disaster.” They focused on essays written by school children from Honjo ward, today’s Sumida ward. From the total of 213 essays, Takada and his colleagues selected fourteen. There were three criteria for choosing the essays: their contents made it easy to understand the circumstances at the time of the earthquake and fires; they referred to landmarks identifiable as Honjo; and they covered various aspects of the disaster, not only tragic subjects related to death and suffering.

After consulting the Sumida Ward Board of Education and receiving permission from school principals and parents, the Tokyo Metropolitan Memorial Association began working with fourteen children from six primary schools (Midori, Koume, Chūwa, Yokokawa, Sotode, and Taihei). The children ranged in age from second grade to sixth grade. Each child read aloud one essay, which was written by a child from the same grade at the same school one hundred years ago. Local children regularly visit Yokoamichō Park as part of extracurricular activities and excursions, as well as for evacuation drills, therefore they are familiar with the local history and did not require any special classes to learn about the Great Kantō Earthquake. Children did, however, receive vocal training. They worked with the local non-profit organization Polaris Rōdoku who provided advice on intonation and other techniques to make their voices clear and easy to understand as they recited the essays. The recordings were made in August 2022.

Ten-year old Hiroki Rintarō recited an essay titled “I Survived,” written by a boy called Sawada Noriyuki. Like Hiroki, Sawada was also in fourth grade at Chūwa Primary School when the earthquake struck. Hiroki’s clear and sincere voice brings Sawada’s words to life. It begins (Tōkyōshi gakumuka, vol. 4, 408–410):

September 1, 1923 was the day of the great earthquake disaster. I had just sat down and was about to start eating my lunch when suddenly gurari the tremors started. At first it shook, gurari, gurari. My mother said to my grandfather, “Should we go outside?” My grandfather was drinking sake and he said, “Don’t worry!” But the tremors continued gara gara gara. Then there was a terrible noise and the shed collapsed. The walls collapsed and lots of debris fell down too. The earthquake got stronger and stronger. Then even my grandfather couldn’t stand it any longer and we all fled outside.

Sawada’s essay then described how he escaped from the fires in Honjo by boarding a boat and the dramatic scenes he witnessed along the way. Hearing Hiroki’s voice read Sawada’s words has a dramatic impact on the viewer on two levels: first, listening to a child’s voice (as opposed to an adult’s voice) and second, hearing the words read aloud (compared to the experience of simply reading the text to oneself) creates a more powerful sensory experience and further amplifies the emotional content. The experience also left a deep impact on Hiroki. In an interview published in the Yomiuri Shinbun on 10 June 2023, Hiroki said, “It was the first time for me to read an essay by someone who survived the Great Kantō Earthquake. I learned a lot about history.” He also felt a sense of empathy with the boy who was the same age and attended the same school. “There may have been many people who were unable to board the boats and did not survive,” he reflected. “I could feel the hardships the writer must have endured.” Hiroki’s mother, Kayo, also reflected on the project. “It was a valuable experience that we can only appreciate now, 100 years later,” she said.

In March 2023, the Tokyo Metropolitan Memorial Association released the DVD titled Shinsai kinen bunshū rōdoku ākaibu.

Figure 6: Shinsai kinen bunshū rōdoku ākaibu DVD cover. Photograph by author, courtesy of the Great Kantō Earthquake Memorial Museum Collection.

The 53-minute recording is accompanied by transcripts of the text and 118 children’s drawings from the Museum’s collection. Each recitation ends with a photograph of the child who read the essay. From September 2023, the DVD will be featured in a new exhibition at the Great Kantō Earthquake Memorial Museum. Reflecting on the project, Takada said, “I hope that these memories of children who experienced the unprecedented disaster will help people to feel what it was like at the time” (Mainichi, 2023). There are plans to use the DVD elsewhere in Sumida ward, and also to offer it to schools and organizations who wish to use it for disaster prevention activities. As Uesugi explained, “It is a record of the earthquake disaster as seen through the eyes of children. We hope it will be useful for disaster prevention education by the ward and fire department” (Tokyo shinbun, 2023).

100th Anniversary Events in Tokyo

Tokyo’s residents have long associated September 1 with disaster preparedness exercises and reminders of the devastation caused by the Great Kantō Earthquake. This year, however, disaster risk reduction experts are using the 100th anniversary of the Great Kantō Earthquake as an opportunity to not only remember the disaster, but also to urge residents to rethink their disaster preparedness in anticipation of the next big earthquake. On the Cabinet Office’s specially created website to mark the anniversary, Tani Kōichi, Minister of State for Disaster Management, describes the Great Kantō Earthquake as “a disaster that deserves special mention in the history of disasters in Japan” (Cabinet Office, 2023). He also urges the public to learn more about the Great Kantō Earthquake and raise their own awareness of disaster prevention, especially given the risk of future large-scale earthquakes directly under the Tokyo metropolitan area, the Nankai trough, and the Japan Trench.

Fire safety is also being promoted. This is not surprising given the fact that fires after the magnitude 7.9 lunchtime tremor killed approximately 96% of the City of Tokyo’s 69,000 victims, and burned over 300,000 houses to the ground. In June, the 2023 Tokyo International Fire and Safety Exhibition included various exhibits to mark the 100th anniversary of the Great Kantō Earthquake and promote fire safety awareness. In addition to a simulation of the magnitude 7.9 tremor that visitors could experience, one exhibit vividly reminded people about the threat of fire following earthquakes. A three-dimensional representation brought to life the “tornado like swirls of flames and smoke known as firestorms” that swept through Tokyo in 1923. Morizumi Akira of the Tokyo Disaster Prevention and Emergency Medical Services Association said, “I want visitors to learn and understand the horror of the Great Kantō Earthquake and rethink their disaster preparedness” (NHK World Japan, 2023).

Museums and libraries are also showcasing earthquake related memorabilia and books from their collections. At a commemorative exhibition in Minato, the Japanese Red Cross Society has paraphrased the expression “Onko-chishin” (温故知新), which means to learn new things from the past, and titled the project “Onko-bishin” (温故備震) to express their hope that by reflecting on the Great Kantō Earthquake, Japanese society will better prepare for tomorrow’s disasters. Items on display include maps showing the location of first aid relief stations and temporary hospitals, a scrapbook of newspaper cuttings from September to December 1923, donated articles of clothing, and a bottle of whiskey from the American Red Cross labelled “for medicinal purposes only” (Japanese Red Cross Society, 2023). At the nearby Sankō Library in Shiba Park a mini-exhibition in June enabled visitors to pick up and browse earthquake-related books and magazines published soon after the 1923 disaster, including all seven-volumes of the Shinsai kinen bunshū collection of children’s essays (Tokyo shinbun, 2023). As I travel around Tokyo this summer visiting 100th anniversary exhibitions, and also as I follow media coverage of the Great Kantō Earthquake, I cannot help but wonder how many individuals have been motivated to review their personal disaster preparedness after visiting an exhibition or reading a news article.

Teaching About Earthquakes and Disaster Preparedness in the Classroom

Like Japan’s disaster risk reduction experts, I am passionate about contemporary disaster preparedness following my own experience of the 1995 Hanshi-Awaji Earthquake. As a historian who has conducted research on the Great Kantō Earthquake for over twenty years, and now as a resident of Tokyo, I am fully aware of Japan’s earthquake risks. As a teacher, I strive to ensure that my students learn both knowledge about Japan’s earthquake history as well as practical skills about what to do when an earthquake or other disaster strikes. I also understand the rewards and challenges of trying to achieve this in the classroom. I once attended a compulsory university lecture on disaster preparedness as a guest. I sat in the back row of the classroom and listened intently as the professor shared practical advice on what to do in the event of an earthquake or tsunami. To my dismay, students either side of me continued to play games on their smart phones. It made me think of seismologist Imamura Akitsune who devoted his career to promoting earthquake education after the 1923 earthquake—how do we get the message through?

I have taught courses on the Great Kantō Earthquake to diverse groups of students at universities in Hong Kong and Japan. We’ve covered topics ranging from social and environmental vulnerability, to relief, reconstruction, communication, contestation, and commemoration. I’ve conducted “mini-museum” classes and shared primary sources from my collection including Taishō-era books, maps, journals, postcards and lithograph prints. Of all the different survivor accounts of the earthquake and fires, children’s essays and crayon drawings always elicit the most profound emotional response. When discussing contemporary Japan and the probability of major earthquakes, I ask students, “Are you prepared? Do you know what to do when an earthquake strikes?” Their responses vary greatly. After reflecting on their personal knowledge and level of preparedness, students share their answers and exchange ideas in a small group. A week later students report back that they have reviewed how they will act at the onset of a tremor (“Drop! Cover! Hold on!”), evaluated physical threats in their environment, updated their evacuation plans, installed an early warning app on their smart phone, purchased emergency food or water for their home disaster kit, and talked about their plans with family and friends.

In addition to teaching earthquake-related history and knowledge inside the classroom, I also believe that practical or experiential learning outside the classroom is valuable. In November 2022, I took my students to Yokoamichō Park in Sumida. I was surprised that none of the students had ever visited before, even those who had grown up in Tokyo. After a semester learning about the Great Kantō Earthquake and 1920s Tokyo, students knew that this ward, lying on the eastern side of the Sumida River, was home to some of the capital’s most vulnerable residents in 1923. Honjo possessed the largest population of children under age fifteen (81,723) and the largest number of primary schools (19). In September 1923 it was also the epicenter of death and destruction in Tokyo. Honjo suffered the highest death toll (48,393) and the highest numbers of missing victims (6,105) and injured (10,236). Honjo also had the second-highest number of homeless people (220,018) after 55,753 houses were destroyed (Borland, 2020).

Students were able to fully appreciate the history and significance of Yokoamichō Park, the site previously known as the former Honjo Clothing Depot where more than 44,000 people lost their lives in a firestorm. We spent the morning examining exhibits inside the Earthquake Memorial Museum and walking around the park.

Figure 7: Students visit the museum. Photograph by author.

Students paused in front of the various memorials such as Ogura Uichirō’s “Statue to comfort the souls of children who were victims of the earthquake” (Shinsai sōnan jidō chōkonzō) (Borland, 2022) and the memorial monument for Korean victims.

Figure 8: Replica of Ogura’s statue by his students Tsugami Shōhei and Yamahata Ariichi, unveiled in 1961.

Inside the Memorial Hall (ireidō) designed by Itō Chūta, we examined the oil paintings lining the walls, read wishes on the “Yume Tōba” wooden stupas, and watched a brief video that tells the history of the 1923 earthquake and the 1945 air raids. We met various staff from the Tokyo Metropolitan Memorial Association who were keen to tell us about the history of the site and plans for the forthcoming 100th anniversary. They seemed surprised that students already knew so much about the Great Kantō Earthquake. I hope that my students will also know what to do in the event of a future disaster.

Conclusion

Historical records documenting children’s experiences of cataclysmic disasters are scarce. The fact that many of these records remain today in published form underscores both the significance of the Great Kantō Earthquake as a major historical event and also the prominent place children occupied in Japanese society in the 1920s. In 1924, City of Tokyo officials explained that they published the Shinsai kinen bunshū on the first anniversary of the Great Kantō Earthquake because despite Japan’s long history of earthquakes and fires, none of the records handed down over the years contained the voices of children. “These books containing records of the great earthquake as experienced by more than two thousand innocent children,” officials declared, “are likely the first of their kind since the dawn of history.” Moreover, they described these volumes as “the most meaningful of all activities to commemorate the earthquake because they will benefit future generations” (quoted in Borland, 2020, 44). Today, as Tokyo marks the 100th anniversary, the children’s essays and the valuable lessons they contain are finally getting the attention they deserve.

References

Borland, Janet. Earthquake Children: Building Resilience from the Ruins of Tokyo. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center, 2020.

Borland, Janet. “In Memory of Future Earthquakes: Controversial New Form and Function of a Commemorative Statue in 1920s Tokyo.” Journal of Material Culture 27, no. 3 (2022): 238-258.

Cabinet Office, Government of Japan. 関東大震災100年. https://www.bousai.go.jp/kantou100/ (last accessed June 24, 2023).

“Hisaiji sakubun koe de kiroku,” Yomiuri Shinbun, 10 June 2023.

Japanese Red Cross Society. 関東大震災100年 温故備震~ふるきをたずね明日に備える~. https://www.jrc.or.jp/webmuseum/column/kantou-100th/ (last accessed June 27, 2023).

“Kantō daishinsai 100 nen: Shinsai yokunen no kinen bunshū o DVD-ka,” Mainichi Shinbun, 3 June 2023, 23.

Midori Primary School, Sumida Ward, Tokyo. https://www.sumida.ed.jp/midorisho/shokai/enkaku.html (last accessed June 14, 2023).

NHK World Japan. “Fire and safety exhibition in Tokyo marks centennial of Great Kanto Earthquake,” June 15, 2023. https://www3.nhk.or.jp/nhkworld/en/news/20230615_16/ (last accessed June 21, 2023).

Nihon no furuhonya. Japanese Association of Dealers in Old Books. https://www.kosho.or.jp

Tokyo International Fire and Safety Exhibition 2023. https://www.fire-safety-tokyo.com/en/ (last accessed June 27, 2023).

Tokyo Metropolitan Memorial Association. 炎の記憶

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tObiQYuuwQY&t=39s (last accessed June 29, 2023).

Tokyo Shinbun.関東大震災直後を絵図などで紹介 29日まで港区の三康図書 館で 当時の雑誌の閲覧も, June 17, 2023. https://www.tokyo-np.co.jp/article/257226 (last accessed June 22, 2023).

Tokyo Shinbun. 関東大震災100年 被災児の作文、墨田の後輩児童が朗読 体験画とともにDVD収録, July 1, 2023. https://www.tokyo-np.co.jp/article/260245

(last accessed July 2, 2023).

Tōkyōshi gakumuka, ed. Tōkyō shiritsu shōgakkō jidō: Shinsai kinen bunshū. 7 vols. Tokyo: Baifūkan, 1924.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Uesugi Toshikazu, Takada Keni’ichi, Matsumoto Akimasa and staff from the Tokyo Metropolitan Memorial Association for kindly meeting me to discuss the Shinsai kinen bunshū DVD project in June 2023.

Notes

The Shinsai kinen bunshū volumes are available in the National Diet Library Digital Collections https://dl.ndl.go.jp/.

Other digital collections of earthquake-related materials include the Tokyo Institute for Municipal Research https://www.timr.or.jp/library/degitalarchives_kantodaishinsai.html, the National Film Archive of Japan https://kantodaishinsai.filmarchives.jp/, the Geospatial Information Authority of Japan https://kochizu.gsi.go.jp/item-categories/18, the Great Kantō Earthquake image archive http://www.greatkantoearthquake.com/ and the Earthquake Children Image Archive www.earthquakechildren.com.