Abstract: The essay explores Japan’s policies of containing infection without heavy reliance on legally imposed lockdowns or digital surveillance. It examines the ‘social measures’ that local governments and the Ministry of Health relied on, including consistent public health messaging, contact tracing, education, with a focus on behavior modification. The pandemic worldwide has highlighted the importance of society in addition to the state in controlling infection. This article points out the benefits of this form of social control as well as its trade-offs, including stress concerning social expectations, informal forms of social control, and incidences of harassment and discrimination against the diseased.

Keywords: Covid-19; Social Measures; Public Health Messaging; Contact Tracing; Self-restraint (jishuku)

The coronavirus which causes SARS-Cov-2 (Covid-19) is carried by tiny, respiratory droplets or aerosols. The droplets can be so small—they are estimated to have a diameter of ¼ micrometer, equivalent to 1/100 of a human hair—that they can drift and linger in the air for hours, protected by the mucins coughed up from the lungs (Zimmer and Corum 2021). The virus spreads silently and asymptomatically; one person can infect many others, each of whom might infect many more, creating exponential spread.

Containing the rapid and invisible spread of the virus in the first year of the pandemic, when vaccines were unavailable and the virus was more deadly, placed a heavy burden on society, social behavior, and social beliefs, leading to shifts in everyday behavior and social interaction, such as masking, handwashing, avoiding crowds and close contact, isolation when sick, quarantine, ‘social distance’, telework, and virtual sociality. It also demanded specific individual choices, cooperation, and everyday compliance with public health guidelines.

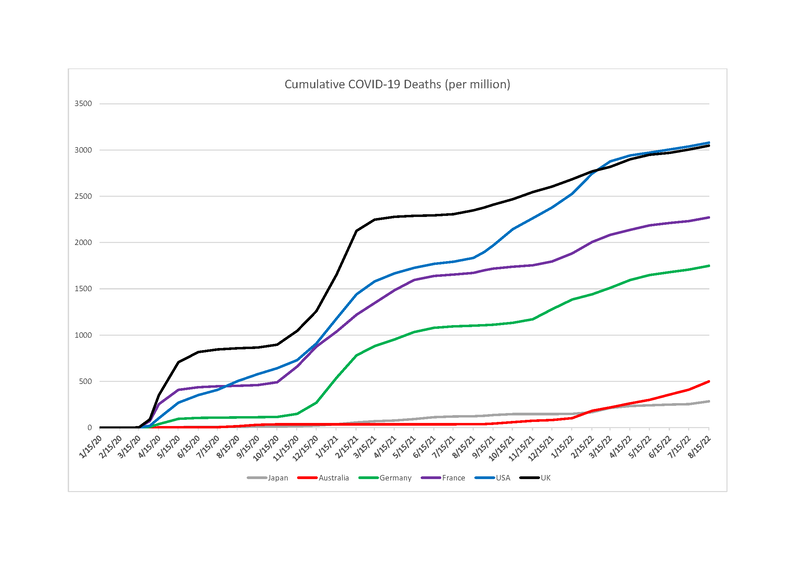

Japan is a particularly interesting place to study these social dynamics during the first year of the pandemic, as all nations were quickly attempting to formulate policies to control the spread of the virus. This is because the Japanese Government relied heavily on voluntary behavior change to combat the spread of Covid-19, as opposed to legally imposed restrictions or lockdowns. What is puzzling and interesting about the Japanese case is that despite relatively lax formal regulations during the first two years of the pandemic, the cumulative cases per million of the population remained far lower than in most other wealthy countries (see Appendices 1 and 2). The cumulative number of deaths per million, even to the present, has also been remarkably low, despite Japan’s proximity to China, the fact that it was one of the first countries to experience the infection outside of China, and that it is an aging society where 28.4 per cent of the population is over age 65.

This is significant because Japanese citizens and residents enjoyed relative freedom, at least relative to many other countries. The prime minister ordered to close schools at the beginning of the school year in April 2020, but within weeks many schools re-opened. Many school and workplace entrance ceremonies went on as planned with physically distanced seating and large numbers of attendees. Workplaces remained open and most people continued to commute to work on crowded public transportation. Shops and restaurants remained open, though limits were imposed by the state of emergency orders beginning in April of 2020. Nonetheless, the Japanese Ministry of Tourism implemented its ‘Go to Eat, Go to Travel’ campaign, offering coupons in certain areas for dining and entertainment to prop up local economies. The Japanese Government adopted no stay-at-home orders, although local governments urged residents to avoid ‘non-essential, non-urgent’ (fuyō, fukyū) trips outside the home. They recommended commuting at off-peak hours, with the goals of reducing the daily commute by 30 per cent of commuters. In Tokyo during the first wave of the pandemic, the governor, Koike Yuriko, asked for closures of museums, gyms, movie theaters, and other commercial spaces (Iijima 2021: 291). Trending hashtags on social media included #お家時間 and #お家で (#home time and #at home). But public guidelines were mostly made in the form of ‘requests’ (yōsei) and in most cases were not legally enforced. This is evidenced by the fact that compliance levels varied. Teleworking, for example, was incompatible with Japanese workplace culture, and Japanese newspapers contained photographs of packed train stations on 8 April 2020, the morning after the first state of emergency was declared. Nonetheless, a further piece of the puzzle is that many recommendations and restrictions were adhered to, despite the absence of punitive legal measures.

In this essay, I would like to reflect on the measures that the Japanese Government and Ministry of Health relied on to control the spread of infection early on, something that we might call ‘social measures’. By ‘social measures’, I mean measures pressed upon all people in the course of daily life, whose adoption relied more on the internalization or acceptance of social norms and guidance than it did not on legal enforcement for most people. Social measures called on people to modify their daily behavior in routinized ways, and this was enforced in part through the social pressure of ‘appearances’ (seken no me), a term widely used to refer to ‘the eyes of society’. In some cases, this pressure took the form of bullying, harassment, and citizen-driven policing, which became a social issue.

The government adopted these measures while keeping society ‘open’, thereby encouraging economic and commercial activity to continue with some exceptions and modifications. Social measures demanded sensitivity to prescribed social norms and bureaucratic guidance. The government called for compliance as a ‘voluntary’ measure—a kind of ‘socially enforced voluntarism’. It is this politics of voluntarism—the operations of social persuasion and internalization of social norms, as well as their enforcement through public judgement and surveillance—that I would like to explore here. These social measures may have played a role in Covid-19 containment, allowing Japan to whether the pandemic while remaining ‘open’ in many spheres. They also came with a psychic and social cost. In what follows, I would like to reflect on these trade-offs and the social containment of Covid-19—the burden that society shouldered which allowed the economy to persist and the government to use softer forms of control.

During the pandemic, all urbanized or densely populated nations had to make decisions about the extent to which they would compromise individual freedoms and rights in the effort to contain the spread of the coronavirus. China enforced mass lockdowns, isolation in public buildings, sequestered infected neighborhoods, and later carried out flash quarantines, location tracking through QR code scans, and months-long lockdowns in workplace environments (Qin 2022). South Korea carried out significant digital surveillance of citizens, including tracking of electronic transaction data, mobile phone location logs, and surveillance camera footage.1

European and Commonwealth nations such as France, Germany, Australia, New Zealand, England, and Italy avoided such heavy-handed measures, but nonetheless passed legal mandates to control peoples’ movements and imposed selected lockdowns which included curfews, restrictions on mobility, closures of non-essential shops—punishable with fines or imprisonment and accompanied by strong statements by national leaders. The United States, too, relied on lockdowns and closures in certain states and municipalities, in the absence of consensus on protocols such as masking and limiting social gatherings.

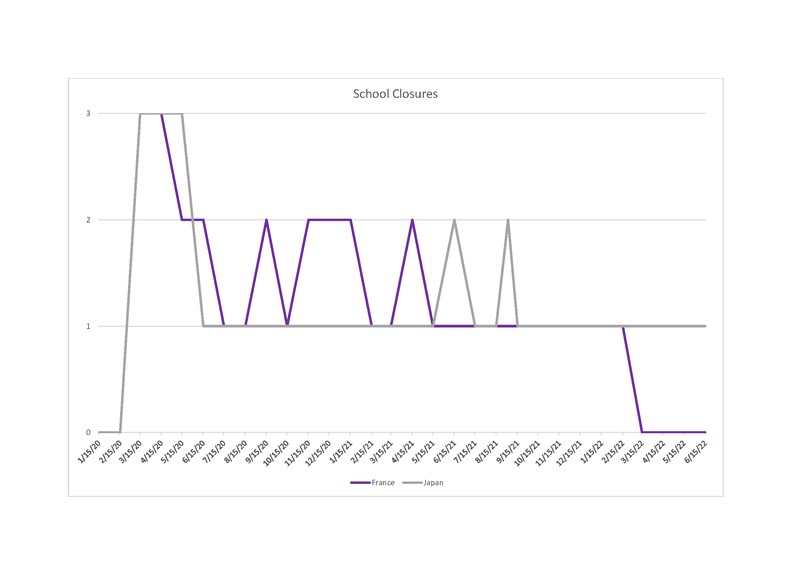

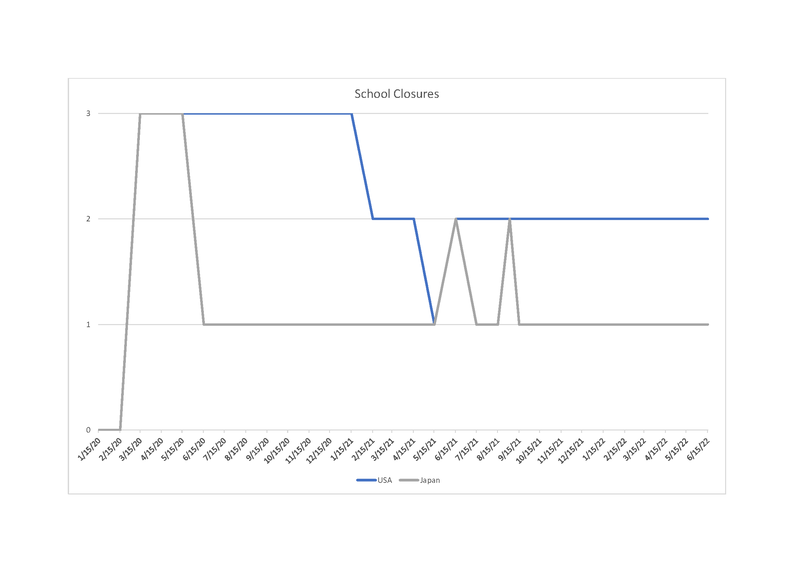

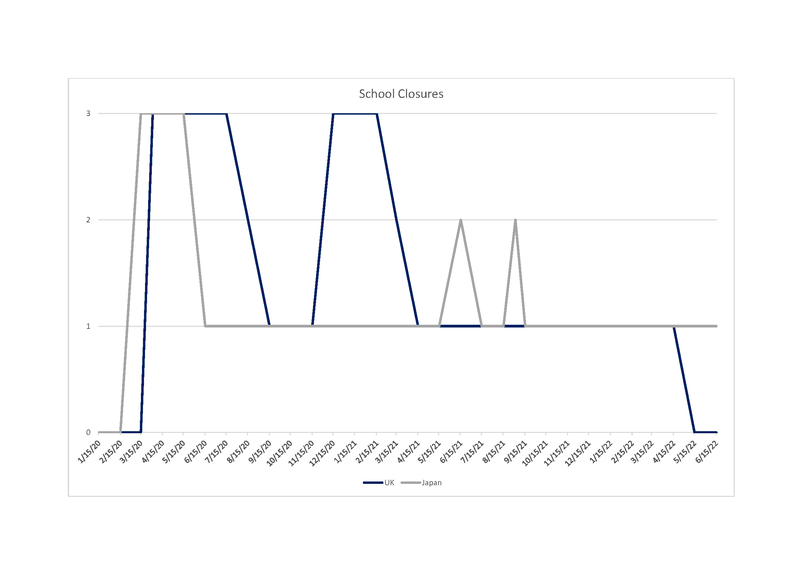

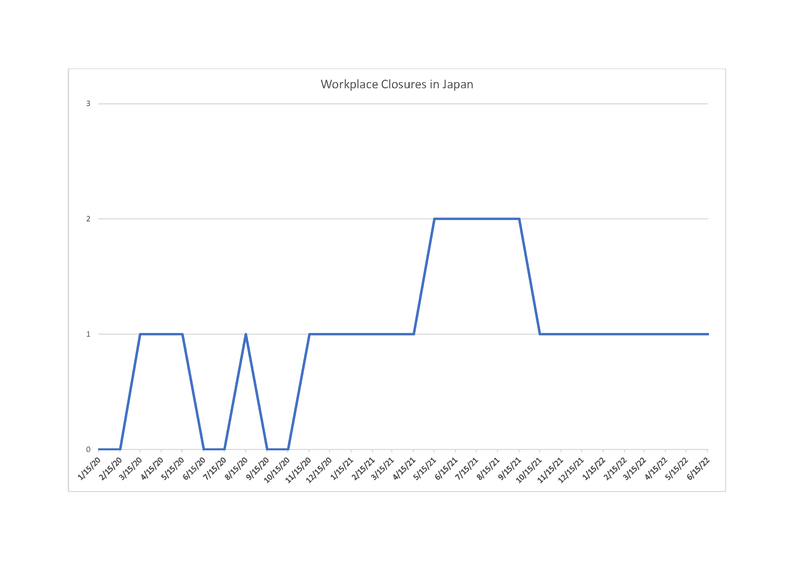

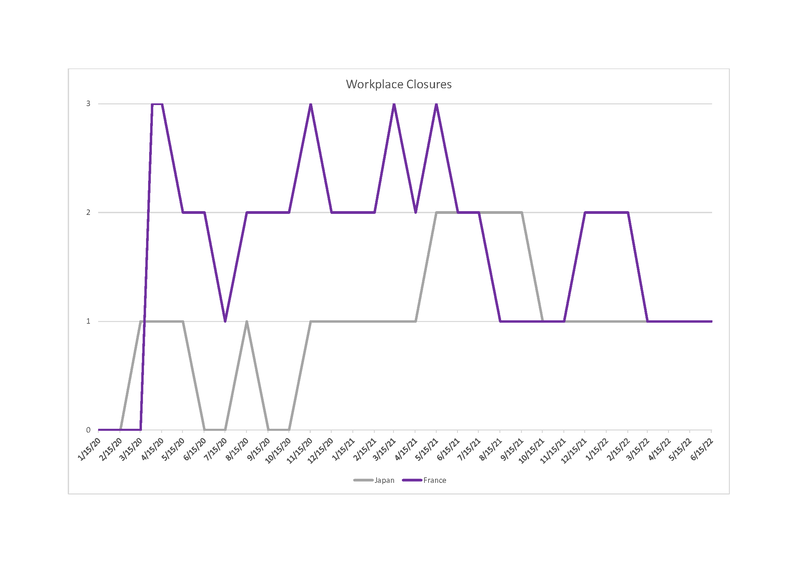

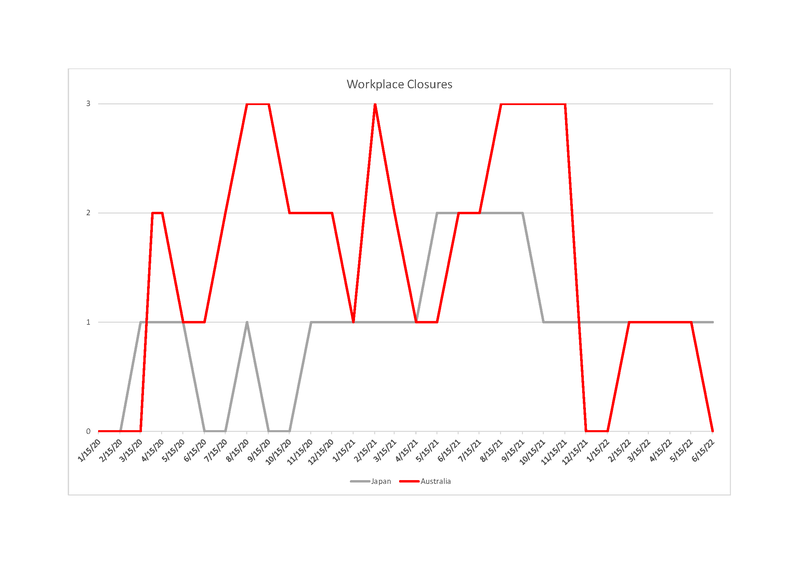

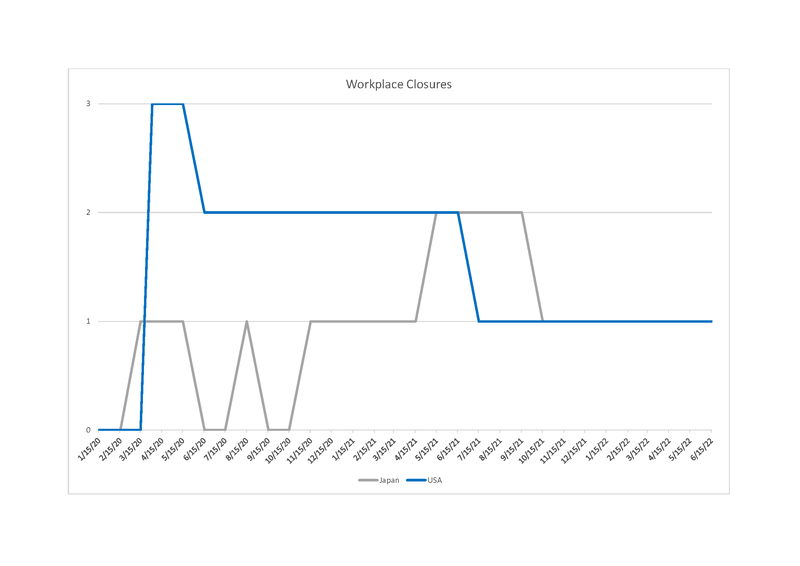

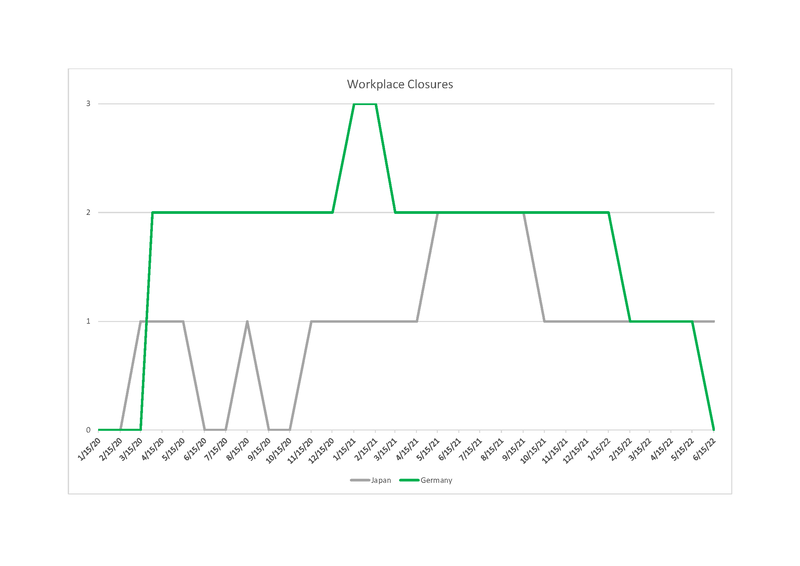

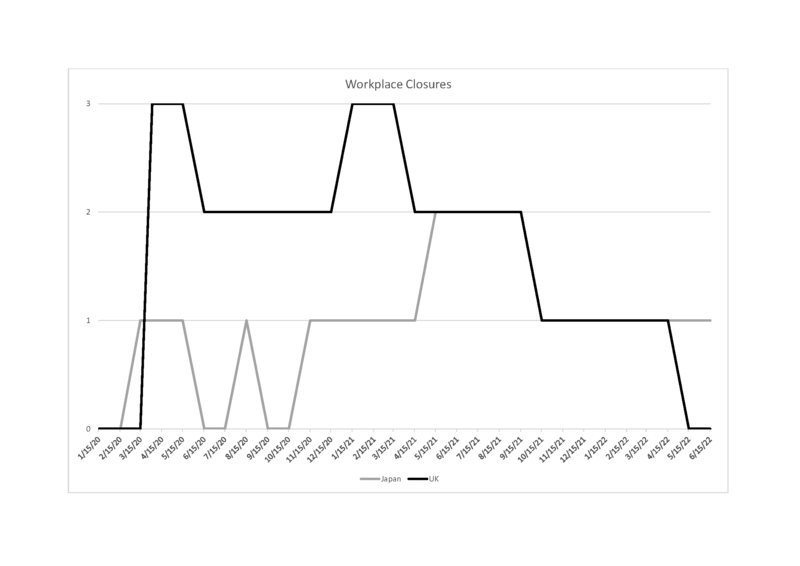

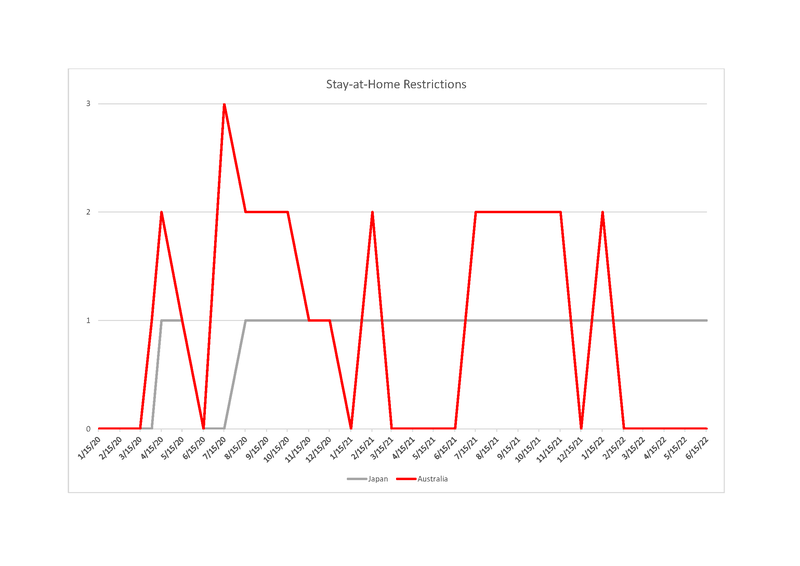

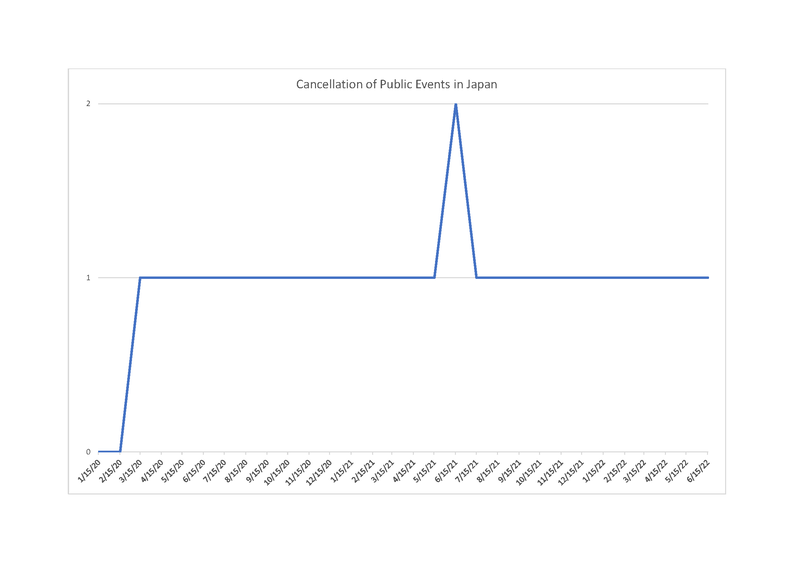

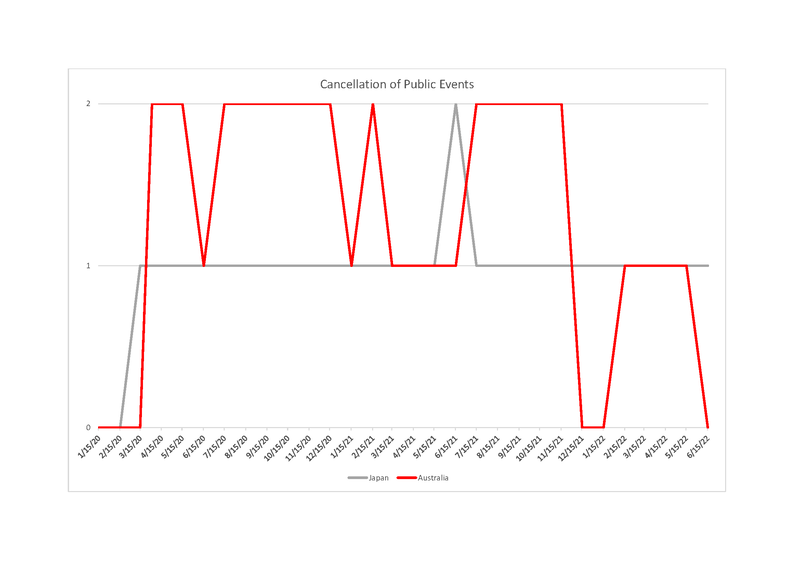

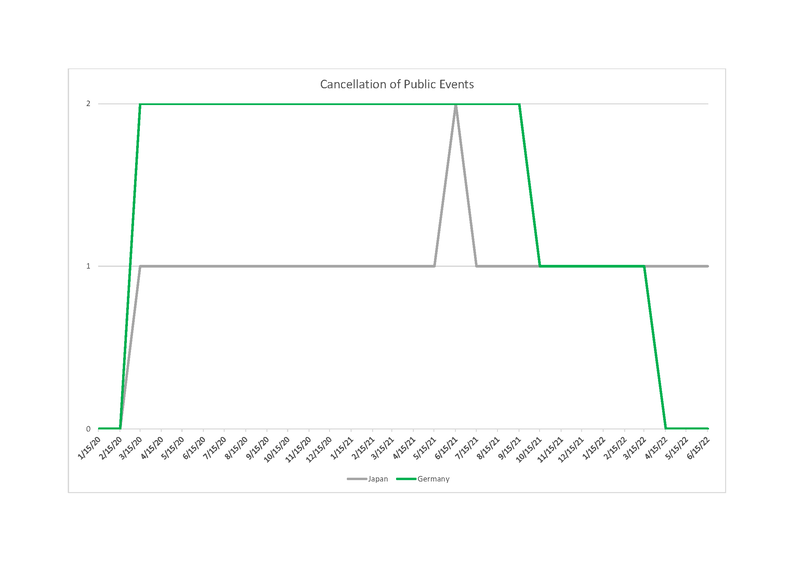

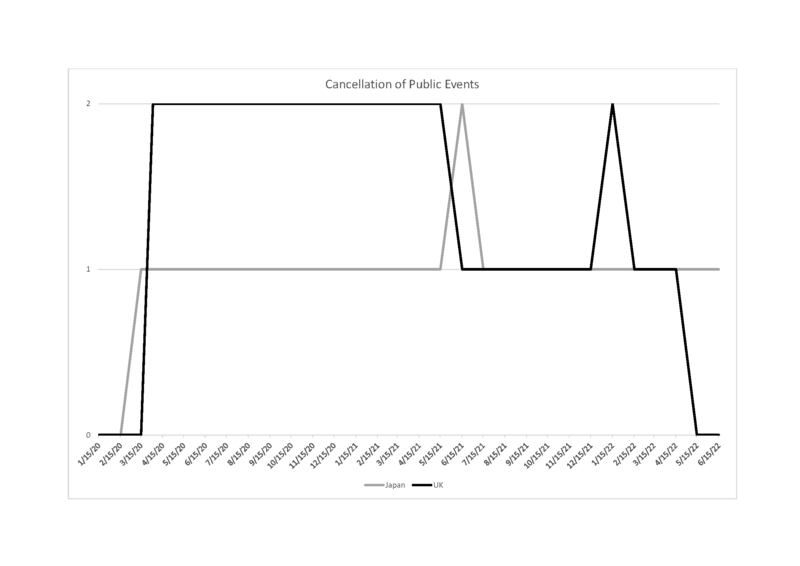

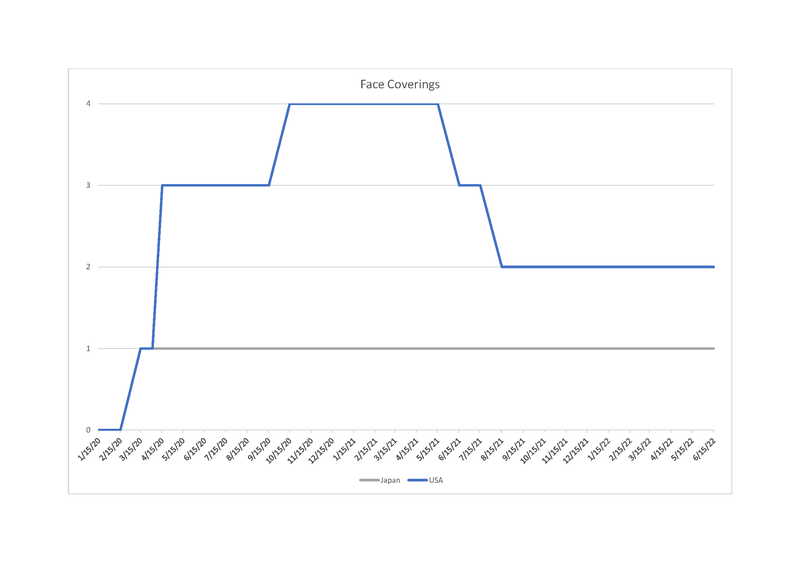

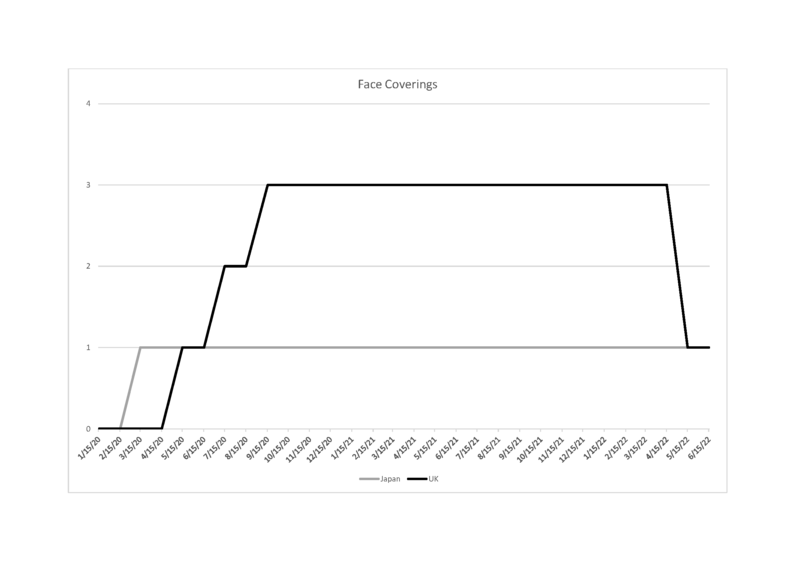

In contrast, if we compare ‘government stringency’ indices in combatting the pandemic in Japan with five other countries—the United States, United Kingdom, France, Germany, and Australia—we see that Japan was lenient in enforcing certain policy measures that had been undertaken with more severity by other nations.2 On metrics of school closures, workplace closures, stay-at-home restrictions, and cancellation of public events, Japan appears in all cases to be less stringent, with mainly optional, or ‘recommended’ policies. Schools closed briefly in spring of 2020 but re-opened and mainly remained open (see Appendix 3). Workplace closures were also optional (see Appendix 4). Stay-at-home orders were also ‘recommended’ (Appendix 5). And, except for the summer of 2021, during the Delta surge, cancellation of public events was not mandatory (see Appendix 6). Though masking was never mandated by law, masking became near universal, reflecting the extent to which masking is considered a social norm signifying hygiene and etiquette (though these norms appear to have emerged relatively recently, since the 1950s [Gordon 2020a]) (see Appendix 7).3

Beginning on 7 April 2020, a series of ‘states of emergency’ (kinkyū jitai sengen) were declared by the cabinet, including in the periods between 7 April and 25 May 2020, 8 January and 21 March 2021, and 25 April and 30 September 2021, which targeted shifting areas. Recommendations became more restrictive, including requests for early closure of bars and restaurants (last order at 7pm and closure at 8pm) and, in some cases, prohibiting the service of alcohol, giving rise to the expressions such as ie nomi (‘drinking at home’) and koen nomi (‘drinking in parks’). However, even these guidelines were made as a ‘request for cooperation’ (kyōryoku yōsei) rather than proper orders. The Japanese cabinet attempted to incentivize shops and businesses impacted by the state of emergency early closure recommendations (Farrer 2020), and it seems that many (or even most) businesses complied with the government’s request.4 In January 2021, two legal amendments were passed which put more teeth into the state of emergency ‘requests’, making it possible to criminally punish those who disobeyed early closure mandates, but it is difficult to know to what extent the laws were enforced.5

We still do not precisely know the mix of factors that allowed Japan to escape with relatively low case numbers thus far. Some scientists have suggested that Japan’s relatively low infection rates may have been caused by biological rather than social factors, for example prior exposure to other coronaviruses, which may have created ‘neutralizing antibodies’ against Covid-19 (Kaneko et. al. 2022). Furthermore, it is important to recognize that Japan’s measures cannot be described as mere ‘requests’ in all cases. For example, the police heavily patrolled nighttime entertainment areas and targeted certain drinking establishments, particularly less expensive ones, including host and hostess bars, lounges, snacks, and cabarets, with devasting economic consequences on a community of precarious workers who work essentially on commission with no benefits or health care (Giammaria 2020; Lee 2020).6

Nonetheless, in this essay I would like to explore this approach to Covid-19 containment from a social and ethical point of view. In what follows, I focus on three areas: public health messaging; contact tracing undertaken by civil servants; and person-to-person policing, surveillance, and peer pressure motivated by the ideology of ‘self-restraint’ (jishuku).

It is fascinating that in the Japanese case, the state’s lighter touch was supplemented, and arguably made possible, by the work that society itself was doing. The approaches I have described reflect a pattern of governance that historian Sheldon Garon (1997) has described as ‘social management’: the use of social persuasion and appeal on moral and spiritual grounds for citizens to comply with desirable national goals. This management of the people has roots in the Meiji era (1868–1912), as the government sought to create a strong, prosperous, and cohesive society, while avoiding the creation of a welfare safety net. The state encouraged industriousness, hygiene, thrift, and temperance, relying on citizens groups themselves to promote desirable behavior (Garon 1997). Through campaigns to improve daily life behavior and ‘moral suasion’, the state reached deeply into the private lives of individuals and molded their beliefs and behavior. Government saw society as a sphere to be cultivated and shaped to produce prosperity, social order, and national loyalty.

We can see resonances between Covid-19 containment measures beginning in 2020 and other public health management measures in recent years—specifically, an emphasis on social control through education, consciousness-raising, and ‘guidance’ (shidō), and a focus on daily life habits (seikatsu shūkan) and ‘health management’ (kenkō kanri). For instance, policies concerned with curbing chronic illness for an aging population have also focused on maintaining life habits and the standardization of healthy behavior (Borovoy and Roberto 2015; Borovoy 2017; Manzenreiter 2012). While public health activists in the United States have frequently emphasized the need for government regulation, Japanese public health activists have often worked around the state, for example in the case of anti-smoking activism, which has emphasized the discourse of ‘manners’ and the burden of cigarette smoke to others (Feldman 2001). There is a strong orientation here to managing health through behavior change, which is brought about by socialization and disciplining of the self through habit-formation, record-keeping, and a positive valuation of social acceptance. These ‘softer’ forms of social control raise fascinating questions, because even while they avoid more centralized, legal, or coercive forms of power, they press individuals to abide by social norms in ways that are keenly felt and difficult to resist. Scholars of Japanese education, particularly early education and socialization in the classroom, have observed these dynamics shrewdly (see for example, Cave 2004, 2016; Peak 1989; Rohlen 1989; White 1987).

Refraining from legally mandated lockdowns reflects postwar citizens’ distaste for the state’s direct impingement on personal freedoms, which has forced the state to rely on heavy-handed mechanisms of persuasion, pressure, and ‘self-control’ (Gordon 2020b; Wright 2021). But in relying on social management, messaging, the invocation of social norms, and the ideal of a common good, these policies also invited a harsh social scrutiny, social surveillance, mutual policing, and pressure to defer to social norms. Thus, while voluntary compliance and deference to social norms and public expectations allowed citizens to avoid the authoritarian touch of the state, these same mandates carried their own forms of coercive pressure, informal policing, bullying, scapegoating, and in some instances discrimination against those infected with the virus themselves.

In a short 2020 essay titled ‘The COVID Exception’, anthropologist Arjun Appadurai has written that Covid-19 has upended assumptions about the power of the state itself and revealed the limits of even wealthy, powerful nations to contain it. States must rely on society for implementing norms and protocols, and this was even true in the case of China, ‘where the dramatic lockdown of Wuhan did nevertheless require public compliance with the state’ (Appadurai 2020: 222; see also Ni et al. 2020). In Appadurai’s words: ‘[T]he arrogance of the nation-state has been dealt a massive blow by the rediscovery of the social resources that managing this crisis requires.’

But what is meant by ‘the social’ in this context? What are its operations? How is it persuasive and compelling? How is it effective—and how is burdensome, or even harmful? Who is included and excluded? (Adams et al. 2019: 3; Nelson 2020).

Reflecting on the early months of the pandemic as it unfolded in Japan, Alexis Dudden (2020: 50–52) commented on the relative absence of the state, represented by then Prime Minister Abe Shinzo’s gesture of sending two (low quality, poorly-fitting masks) to every Japanese household. While Western European nations imposed extended lockdowns, Japan, like the United States, declined to impose national orders and placing the burden of containing infection on citizens themselves.

At the same time, we know that statements by the national government were supplemented by many measures, including a heavy dose of ‘guidance’ and public messaging from the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare (MHLW) and from local governments, institution-specific rules and ‘requests’, prefectural and municipal rules, and community health care. Indeed, Covid-19 restrictions were felt in most aspects of daily life despite the government’s permissive posture. Regimes of social norms, public health messaging, and informal policing turned out to be so influential that the imposition of legal punishments was perhaps less necessary. I am interested in the operations of those supplementary measures of social control, in what made them persuasive, and in reflecting on their effectiveness and costs.

The public health emphasis on individual compliance with government guidance created social pressure, anxiety, and stress in ways that were in some ways parallel to the responsibility placed on individual citizens in the wake of the triple disaster and nuclear meltdown at the Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant (for instance, see Abe 2016 and Kimura 2016).7 The emphasis on individual comportment and culpability also fueled long-standing prejudices, including against professions considered undesirable and ‘dirty’ or promoting contagion, specifically the sex trades (Giammaria 2020). It arguably invited stigma against infected individuals themselves. A Covid-19 containment policy which kept businesses open protected some workers but also put others, who lacked basic protections, at greater risk (Ando 2020; Giammaria 2020; Slater 2020; Slater and Barbaran 2020; Tanaka 2020; Tran 2020). In other words, Japan’s case shows us that the policies which avoided the harms associated with complete lockdowns did not come for free.

My focus is on the first year of the pandemic, before the development of the Covid-19 vaccine, as governments frantically developed policies to contain the spread of infection. Japan’s response then remains relevant to understanding vaccine uptake and continued masking, both practices that are important in attempting to contain the spread of the evolving variants (see Gordon and Reich 2021).

Research for the article was conducted without visiting Japan and cannot offer ethnographic analysis of what it was like to experience the pandemic, as other articles have done, including in this journal (Farrer 2020; Giammaria 2020; Slater and Barbaran 2020; Tanaka 2020; Tran 2020). My research consists of surveying the mainstream news media at regular intervals beginning in February 2020 (focusing on the Mainichi Shinbun, Asahi Shinbun, including features and first-person testimonials, and the Asahi photobank), checking local prefectural and city government websites, following statements by Japanese scientists who were advising the MHLW, researching contact tracing training and protocols, and looking at Red Cross public health advice, in addition to Zoom interviews with friends and colleagues in Japan. While the Covid-19 puzzle in Japan is something that has been widely commented on, perhaps it is useful now (though the pandemic is ongoing) to consider both the benefits and costs of Covid-19 containment policies from a distance.

Public Health Messaging: ‘Density’

Michael Reich (2020) has written that a key aspect of ‘pandemic governance’ is ‘the use and clarity of information’. The public health messaging to contain coronavirus transmission in Japan focused from the beginning on the idea of avoiding ‘density’. The message was science-based and memorable. It also placed a great deal of responsibility on individuals and institutions to re-organize social behavior beyond social distancing, including online sociality, off-peak commuting, and seeking separation in dense urban places where space was short.

Messaging from the MHLW and the Prime Minister’s cabinet office from February 2020 converged on a shared and science-based message to urge people to modify their behavior. This messaging cautioned people to avoid ‘three kinds of density’: enclosed spaces with poor circulation (kanki no warui, mippei kūkan); crowded spaces and spaces where large numbers gather densely (ooku no hito ga misshū suru basho); and close interpersonal interaction or ‘proximity’ (missetsu bamen), or settings where conversation takes place at close range (kinkyori de no kaiwa, hassei). The ‘three densities’ (mittsu no mitsu) was a message rooted in a mnemonic repetition—highly digestible and memorable. All three phrases used the same character, ‘mitsu’ (密). Furthermore, the word for ‘three’ (mittsu) in Japanese is a homophone for the Japanese reading of the character for ‘density’ (mitsu) itself.

Posters carrying the message designed by community health centers, city governments, and the MHLW were found on prefectural and city government websites, hospitals, neighborhood association (jichikai) poster boards, and public transportation. The same message accompanied the two masks notoriously sent out by Prime Minister Abe’s office in April 2020 and was also promoted on the Japan national broadcasting channel (NHK), other TV advertising, in banners over commercial streets, flyers given out by universities, and via social media. There is evidence that the message raised public awareness about ‘closeness’ and ‘density’. In 2020, the ‘three mitsus’ was selected as the ‘internet buzzword of the year’ and the Chinese character of the year by the Japan Kanji Aptitude Testing Foundation.

The message was so ubiquitous that it soon became an internet meme. After Tokyo Governor Yuriko Koike held a press conference in April 2020 where she repeated the phrase ‘mitsu desu!’ (‘Too close!’) to caution the press to keep their distance, DJ Barusu (DJばるす) sampled her words in an EDM track titled Mitsu desu beat, which closed with Yuriko’s exhortation ‘Everyone: let’s overcome this together!’ (DJ Barusu 2020). At the time of writing in November 2022, this YouTube video had received 7,347,963 views. Other YouTubers also set the words to music and invoked public health sound bites in skits. Some video games did the same, including one featuring Governor Koike, flying over Tokyo, super-hero style, landing to bust up clustered individuals with her martial arts-style moves with a sampled voice-over (Mitsudesu 3D 2020). The remix and games are playful but not exactly satirical. Koike was re-elected as governor by a wide margin in July 2020.

Figure 1: DJ Barusu’s remix of Governor Koike Yuriko’s April 2020 interview with the press. Source: DJ Barusu 2020.

Figure 2: A video game called Mitsu desu 3D: Mitsu shūdan o kaisan seyo [Mitsu Desu 3D: Break up the Groups!]. Source: Mitsudesu 3D 2020.

When I interviewed a teacher at an English language cram school in Kanagawa Prefecture (outside of Tokyo) in March 2021, she told me that her protocols revolved around the fundamental principle of ‘avoiding mitsu’ (mitsu o sakeru). This included handwashing, measuring body temperature, air flow control and purification, and seating students in ‘zigzag fashion’ (seki o barabara) around a table, so that students did not directly face one another. A kindergarten teacher and middle school counselor also both told me that students eat lunch in a line facing forward rather than around tables opposite one another. Students are instructed to eat silently (mokushoku), and it seems that this guidance continues in many schools.

|

|

Figure 3: Left: Posters exhorting to ‘avoid the three kinds of mitsu’ from the website of Akita City;8 Right: ‘A New Lifestyle’, published by Fukushima Prefecture as part of its ‘New Normal’ campaign.

The three points I would like to emphasize about this public health message are: 1) it was a science-based message which turned out to be digestible, accurate, specific, and actionable; 2) it sensitized individuals to a high degree concerning issues of ‘air’, ventilation, and proximity in ways that the American guidance of keeping ‘six feet’ (or two meters) of distance did not; and 3) it also placed a burden on individuals to avoid comportment that could lead to infection and sometimes led to stress and conflict.

Behind the san mitsu public health sound bite was a scientific theory which determined the public health response and shaped the landscape of Covid-19 sociality. According to Hitoshi Oshitani, a respiratory disease specialist and member of the government task force who became an outspoken voice in educating the public, emerging science was in part informed by the story of the Diamond Princess, the outbreak on a large cruise ship docked in the port of Yokohama in February 2020, in which 712 of the 3,711 people on board, as well 9 quarantine officers and health care workers who intervened to manage the outbreak, became infected. Since these workers would have taken basic hygienic precautions as experts in disease control, it seemed unlikely that large respiratory droplets (fluid droplets expelled from the respiratory system) could be the main cause of infection, as some had suspected. In addition, early contact tracing suggested that certain individuals were hyper-infectious. With the virus spreading quietly, asymptomatically, and ‘stealthily’, Oshitani and colleagues agreed that containment through lockdowns would not be possible or would come at too high a social and economic cost. Citizens would need to ‘live with Covid-19’—in the sense of keeping society open while coping with the virus. This realization gave rise to the message of avoiding the three forms of density (Oshitani 2020). As Oshitani said in a presentation at Tōhoku University Medical School: ‘Everyone in Japan should look at your own actions and change them. The message is: behavior modification, behavior modification, behavior modification!’ (Kōdō henyō! Kōdō henyō! Kōdō henyō!) (Oshitani 2020b, slide #55).

The social messaging around mitsu sensitized people to the dangers of proximity, closed spaces, and exchange of air, even while workplaces remained open and people were expected to commute to work. It put pressure on Japanese citizens to behave in appropriate ways and invited others to observe and criticize individual behavior, particularly in the context of crowded public transportation. The term ‘corona harassment’ (korona harasumento or korohara) came to be used to describe the public policing of etiquette and masks. Stories in the mass media and videos posted on social media captured tense scenes. In February 2020, NHK reported that someone pushed the emergency button on a train in Fukuoka and the train stopped, because a passenger was coughing violently without a mask (NHK 2020a). A video posted on Twitter captured a tense scene in which a man expressed outrage after a woman sneezed on a crowded train, while another man loudly confronted the first man for being inappropriate (@__Aerials 2020). In another incident that occurred on 16 June 2022, the JR Yamanote-line stopped for 47 minutes for a quarrel in the train regarding someone clearing their throat (sekibarai) (Mainichi Shinbun 2022). Japan TV reported that complaints were rising about those not following masking protocol on public transport. A survey conducted by the Japan Association of Private Railways in December 2021 reported that passengers were concerned about those violating mask protocols (74.4 per cent), nearby conversations (shūi no kaiwa) (55.0 per cent), the proximity of the next passenger (tonari no hito no kyori) (47.6 per cent), and the issue of ventilation (shanai no kanki) (41.8 per cent) (Japan Private Railway Association 2021).

While the MHLW also used the language of ‘social distance’ (as did Koike Yuriko), it offered additional recommendations as well (see Figure 3). It recommended embracing a new ‘lifestyle’ approach (atarashii seikatsu yōshiki), including avoiding face-to-face interactions, paying attention to levels of infection in places one visits or works, thorough ventilation, ‘cough etiquette’ (seki echiketto), hand hygiene (shushi eisei), measuring one’s body temperature before leaving the house, keeping a memo of whom one meets and where, engaging in online sociality, shopping in small numbers, resorting to credit card or digital payments (rather than cash transactions), ordering take-out food, eating on individual plates (rather than sharing large dishes from serving plates as is customary), keeping conversation brief (kaiwa wa hikaeme), telecommuting, off-peak commuting, and using a contact tracing app. Other posters illustrated how to wear a mask and ‘three ways to cough’ (with a handkerchief, in one’s elbow, or with a mask). MHLW campaigns also targeted young adults under 30 (who comprised 40 per cent of infections) through social media, including the mega-platform LINE.

It is worth contrasting this message with the standard guidance circulated in the United States and Europe, which was to leave six feet (two meters) between oneself and another—a message that was also used in Japan, but together with the discourse of san mitsu. ‘Six feet’ turned out to be ambiguous and misleading in key respects. Its origin seems to lie in the initial belief that the coronavirus was spread through respiratory droplets which would travel in the air no further than six feet. However, as it became clear that the virus was transmitted through much smaller aerosolized particles which travel greater distances and can float and circulate about a room, the guidance became less useful. While American public health guidance remained focused on sanitizing surfaces and avoiding large-scale events even outdoors, evidence mounted that most transmission was taking place in enclosed spaces through the air.

Eventually, engineering firms and experts in buildings systems who consulted for the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) showed through simulations that ventilation is key to diminishing the concentration of airborne contaminants. They showed that in a typical pre-pandemic classroom, 3 per cent of the air that each student breathes was exhaled by other students. A combination of air filtration and ventilation dramatically reduces the density of contaminant. The theory of respiratory droplets created a misplaced emphasis on cleaning surfaces. It focused on the metric of ‘six feet’, even though six feet may not be safe in an enclosed environment. Conversely, in an environment with proper ventilation, or outdoors, less than six feet may be safe.9 In March 2021, New York City changed its rule from six feet of social distancing to three in elementary and middle schools (assuming transmission is low), citing a study which compared schools with three feet and six feet of distance and found no significant difference in levels of transmission (van den Berg et al. 2021). Later the CDC dropped its metric of ‘six feet’ entirely.

Japan’s public health guidelines more actively embraced scientific knowledge from an early moment, even though scientific understanding of the virus—its structure and transmission—was shared internationally through working papers and public disclosure of laboratory findings. Societies responded and acted on that information differently, and Japan’s ability to embrace and act on the message of ‘density’ (despite the fact that 91 per cent of its population lives in urban areas characterized by high levels of population density and crowded transit stations, streets, and schools) reflects the compliance of its society. As early as March 2020, socially distanced entrance ceremonies for large numbers at school and companies were taking place, young children were asked to eat silently, and restaurants were separating customers with acrylic sheets. Compliance with masking was widespread (see Figure 4). Absorbing this message placed a significant burden on social organizations, schools, workplaces, commercial venues, and individuals.

In response to the question of why the CDC delayed acceptance of the finding that the virus was usually spread through aerosolized particles rather than respiratory droplets, some have suggested that one reason was that ‘our institutions weren’t necessarily set up to deal with what we faced’ (Tufekci 2021). Health-care facilities, which are already well-ventilated, prioritized handwashing as a measure of bacterial control. Other public facilities tend to be sealed as a means of insulation. Masking, ventilation, and avoiding loud vocalization are the most effective means of containing transmission in that context, but these were difficult to embrace and to impose universally (Tufekci 2021).

Many of the norms and protocols that were imposed on Japanese people and residents during the first year of the pandemic have now become engrained in public life, normalized and facilitated by automated technology, including visible cameras which check to make sure customers are masked before entering a store, or thermometers at the entry to public spaces such as libraries or schools. (In some cases, if an individual is not wearing a mask, an automated voice will request that they put one on.) Prefectures have incentivized businesses to comply with public health guidelines through a certification system (ninshō seido) which shows that the shop is complying with MHLW guidelines including masking, sterilization, proper air circulation, and use of plastic shields (akuriruban) between customers.10

Figure 4: Employees undergoing a socially distanced entrance ceremony for Nishi-Nippon Bank in Fukuoka City. Source: Takahashi et al. 2021.

Japan’s response reflected shared scientific findings. Those findings demanded compliance with new forms of social behavior and social organization. Compliance was imposed by workplaces, schoolteachers and counselors, and embraced by individuals in public in ways that at times became stressful and contentious. Nonetheless, the emphasis on ‘closeness’ and ‘density’ was arguably more effective than the metric of ‘six feet of distance’ that was ubiquitous in the United States.

Contact Tracing: Surveillance, Empathy, and Persuasion

In the first year of the pandemic, Japanese scientists focused on contact tracing as a solution to reducing transmission. They relinquished testing as a form of containment, and instead mobilized Japan’s public health infrastructure to undertake a labor-intensive and demanding form of public health education and surveillance through extensive contact tracing. Their logic was that PCR testing was an impractical solution. SARS-Covid-2 (Covid-19) was a different disease from SARS-Covid-1, the pathogen that had caused a deathly outbreak in China in the early 2000s. SARS caused by that pathogen usually manifested in severe illness within 2 to 14 days. In contrast, Covid-19 was spread asymptomatically. To find asymptomatic spreaders, one would have to test every person in a chain of infection (kansen rensa). PCR testing was a weak tool to contain the threat of infection ‘clusters’—those who might have been exposed and might expose others before they became symptomatic (Oshitani 2020a and 2020b).11

Contact tracing was handled by a competent, highly trained, and experienced body of workers: Japan’s public health nurses (hokenshi), many of whom are trained civil servants who work at local community health centers (hokenjo). Public health nurses pass both national examination for civil servants and also a more specific one for their municipal area. They are outward-facing and responsive to community needs and education concerning chronic illness, mental health, prevention, and screening. The hokenjo is a source of information, ‘health management’ (kenkō kanri), and ‘guidance’ (hoken shidō). Hokenshi are also supposed to be a deeply rooted (nezashita sonzai) presence in the community and possess ‘intimate’ connections with residents (jūmin no mijika na sonzai) as they engaged in activities of health promotion and support including education and screening (Borovoy and Roberto 2015).

The hokenshi were delegated the work of contact tracing in part because of their experience in handling infectious disease outbreaks including TB, Hepatitis A, chicken pox, and the seasonal flu. They are the ones responsible for managing outbreaks in public schools, mapping cases, and making decisions about classroom or school closures.

Public health nurses are known figures in Japan; they are often described as efficient, knowledgeable, and brusque. The nurse may visit a home in the neighborhood after a baby is delivered to confirm the health of the newborn and mother and to offer support. While there, they will also check that the home environment is suitable for the baby and free of signs of abuse or neglect. The public health nurse is known to be polite, ‘efficient’ (tekipaki shite iru), and a little like a ‘nosy grandmother’.

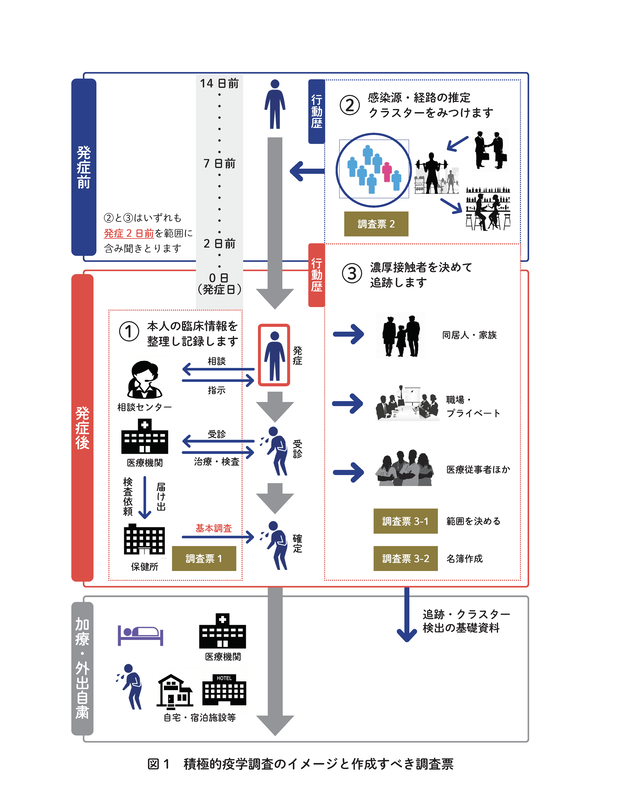

In what follows, I describe the work of contact tracing based on a cabinet level report published by the Coronavirus Task Force of the MHLW (2021). This report contains a manual with detailed written protocols for hokenshi on how to conduct the contact tracing interview (Yoshikawa et al. 2020).

The objectives of the 30-minute interview or ‘active epidemiological investigation’ (sekkyoku teki ekigaku chōsa) were to: 1) Obtain a detailed history of the individual’s activities going back two weeks as the starting point of the investigation; 2) Attempt to determine the origin of the infection and guess its path; 3) Identify close contacts (nōkō sesshoku, literally ‘thick contacts’) and preventing them from having contact with others through voluntary but expected quarantine (gaishutsu jishuku); and 5) Identify any potential sources of cluster infection in order to stop the chain of infection (kansen rensa). These tactics make it difficult for the individual to resist the hokenshi’s work to gather information and control individual behavior.

Japan’s contact tracing seemed distinctive in certain ways. Contact was made person-to-person via telephone, not a digital app. Individuals were required to keep in touch with the hokenshi by checking in or replying to texts and to provide an account of all their movements going back 14 days prior to the date of diagnosis to ascertain close contacts (ushiromuki no tsuiseki). The active epidemiological investigation could be described as pedagogically informed public health education in real time through surveillance, nudging, empathy, ‘cooperation’, and education. It is a form of social control that relies on the presumption that the nurse is acting in the interests of the patient, a presumption not entirely false as the hokenshi’s stated purpose is to educate and support.

The MHLW report contains the hokenshi’s interview script, a script that seems designed to elicit cooperation while also expressing empathy. The hokenshi begins with a self-introduction using formal speech: ‘My name is xx from xx hokenjo. How are you feeling today? I’m calling today because we received confirmation of your positive Covid-19 diagnosis. I’d like to talk to you about your current situation and your recent activities and movements. The conversation will take 30 minutes. Is this a good time to talk?’ They explain that the hokenjo has been notified of the individual’s positive Covid-19 test result and explain the goals of the investigation. If the interviewee cannot speak at the present time, the hokenshi will ask for a preferable time to call back, but the person is not given the option to decline the interview.

The hokenshi should seek ‘understanding’ (rikai) from the interviewee of the essential nature of the interview for stopping the spread of infection (kansen kakudai o fusegu). The request for ‘consent’ (nattoku) and ‘understanding’ seeks the interviewee’s buy-in, but the line between voluntary and enforced compliance is fine. In addition, the hokenshi is reminded to be empathetic in the interests of soliciting cooperation. The guide suggests using the following phrases: ‘This has been difficult, hasn’t it?’ (tsurakatta desu, ne?) and ‘You must be anxious about what might happen, isn’t it?’ (kono saki dō natte shimau ka, shinpai desu ne?). The manual states: ‘To the extent possible within the allotted time frame, express sympathy in response to the patient’s anxiety, while continuing to request his/her cooperation’ (Kagirareta jikan no naka de kanja no fuan ni kyōkan shitsutsu mo kyōryoku o irai suru). The manual also instructs the hokenshi to listen by repeating the interviewee’s words at each pause and interjecting short verbal acknowledgements (aizuchi o tataku), in order to encourage the interviewee and solicit cooperation.12

Figure 5: A contact tracing guide. ‘A patient tests positive and the active epidemiological investigation begins: trace the person’s activities backwards for 14 days; find the origin and estimate the path of infection (kansen keirō no suitei); and pursue and notify close contacts (nōkō sesshokusha) including family members, health care providers, and other private gatherings.’ Source: MHLW 2021.

A sample of the questionnaire that hokenshi are asked to complete is provided below (see Figure 6). For each day beginning with 14 days before the onset of symptoms, the individual is asked to report on his or her activities, including time and place, contact with others, conditions (whether it involved contact with others, scale of event, presence of others who were not feeling well), and others who accompanied the individual.

Figure. 6: Sample 14-day contact tracing form. Source: National Institute of Infectious Diseases (click on chōsahyō 5/29/2020 for revised questionnaire).

In this sample, the individual being interviewed attended a live music club and two colleagues from ‘Sales Division 2’ accompanied him. Three hundred people attended the music event which was standing room only. Later he rode a tourist bus (the sample notes the bus company’s phone number) with his wife and two children (‘Tarō’ and ‘Hanako’). There were 20 passengers and one felt ill. Later in the afternoon, he had a conversation with a friend in front of the station for 30 minutes while he was not wearing a mask. The form contains a column for names for those who were present in high-risk situations.

Some scientists described the decision to track clusters rather than test individual cases as a uniquely Japanese approach (Kakimoto et al. 2020; Oshitani 2020a and 2020c), and the pandemic gave rise to a good deal of public health nationalism. ‘Cluster-busting’ was also criticized for its unevenness and potential to target certain areas or populations (Yano 2020; Lee 2020). When the first state of emergency was declared over on 25 May 2020, Prime Minister Abe Shinzō addressed the people at a major press conference, championing the power of Japan’s ‘unique model’ in containing the virus (Nippon moderu no chikara) (Prime Minister’s Office of Japan 2020). Abe began by reporting on the mandatory lockdowns in other countries and said that the Japanese Government had not and could not impose limits on individual mobility enforceable by punishment, even in the context of the state of emergency measures. However, the ‘Japanese way of doing things’ (Nippon nara de …no yarikata) had brought the current wave of infections under control in just one month and a half. This was because of the cooperation of all citizens (kokumin no minnasama no gokyōryoku) and their ‘tenacity’ (konki) and ‘endurance’ (shinbō), as well as the sense of duty of health care providers and public health nurses.

In fact, it is difficult to measure the effect of contact-tracing initiative activity, since many other measures were also in play, including the widespread use of masks. It was likely less meaningful in large cities, where the path of infection is more difficult to trace. And one might argue that contact tracing was basically the only thing that Japanese authorities could do in response to the sudden onset of the virus, when PCR tests were available in only limited quantities and setting up mass testing sites created logistical headaches.

Nonetheless, it seems likely that this measure had an effect on public health consciousness. Interviews themselves were a form of surveillance, reminding individuals that engaging in risky behavior would elicit unwelcome and prying investigations. Furthermore, the interview worked as a form of social persuasion, made hearable by empathic listening. The hokenshi uses the inclusive, first-person plural, ‘we’ and its imperative form, ‘let’s’, to convey a sense of shared purpose. The script makes a plea for ‘cooperation’ (kyōryoku) and includes statements such as ‘Please, let’s work together to avoid further spread of the virus’ (zehi kyōryoku shite itadaki, uirusu no kansen kakudai o fuseide ikimashō). The script encodes a combination of empathy and persuasion, an effective means of eliciting compliance and diminishing resistance.

The community health system shouldered considerable affective labor in educating and socializing the public to contain the spread of infection. The burden of this emotional labor is addressed explicitly in the manual. The appendix of the manual provides suggestions for self-care, such as notice your stress, support one another (sōgō shien), job rotation, perform stress checks, and hire a psychiatrist or psychologist as consultant. First-person stories recounting exhaustion and overwhelm were published in nursing bulletins (Kawanishi and Murai 2020a). The guide also provides guidance for dealing with angry, non-compliant individuals (‘Try to listen and understand their feelings’; ‘Make a plan within the office to deal with a difficult individual’; or ‘Have a male person go to the phone’).

It seems likely that consistent, pervasive, and science-based messaging contributed to effective containment of the virus. And while we do not know how effective contact tracing was per se, it too contained an educational element and functioned as a soft form of social control that was paternalistic and difficult to oppose. The focus on individual behavior modification helped avoid the need for legally imposed lockdowns. In a sense, society was supplementing the work of the state and bore the burden of controlling the people. In what follows, I explore the power of this form of social control and self-control and its darker sides.

Moral Governance: Harassment, Discrimination, and the Self-Restraint Police

In encouraging people to stay at home during the first state of emergency, telework, and socialize through online platforms, the cabinet’s task force consistently used the phrases ‘gaishutsu jishuku’ and ‘idō jishuku’: voluntary self-restraint, self-discipline, or self-imposed control. This discourse reflects the government’s reliance on a language of persuasion, which links social behavior to moral character and addresses itself to the psyche and spirit of the citizen. It also mobilizes citizens to watch and motivate one another (Garon 1997).

The discourse of jishuku (‘self-restraint’, as translated above) is associated historically with wartime restrictions on consumption and national events such as the death of emperors Meiji (Iijima 2021; Watanabe 1989). The term is composed of the characters ji (self) and shuku, meaning ‘solemn’, ‘quietly’, or ‘softly’ (Wright 2021: 462). James Wright describes the way the word seeks to elicit sacrifice and solidarity. While it is often used to request institutions or individuals to compromise their constitutionally granted rights or freedoms (for example requests to companies to refrain from investments in South Africa during apartheid) in order to accommodate a political request, the language implies that the act is self-initiated and voluntary (Wright 2021: 462–63). Wataru Iijima (2021: 294) has defined the term as the ‘disciplined pressure of collectivism’.

A newspaper database search on the term turns up articles from the 1930s and 1940s recommending modesty and restraint. These articles show the way in which compliance or non-compliance with self-restraint and government guidelines is linked to the discourse of morality, proper comportment, and inner character. Thus, violating guidelines might invite judgement or reprimand, as it did in the case of Covid-19. For instance, one article from 27 July 1939 recommends ‘jishuku’ summer hairstyles (jishukukata no natsu no kami) and illustrates an ‘easy-to-tie summer bun’ (tegaru na yuiage) which ‘anybody can do in just 5 minutes’. The piece goes on to say: ‘It’s not just that time-consuming and elaborately decorated (gota gota sōshoku) hair-dos are not summer-like, but it also symbolizes a lack of inner awareness of the current situation’ (ninshiki busoku o sono mama shōchō suru you na mono desu).13

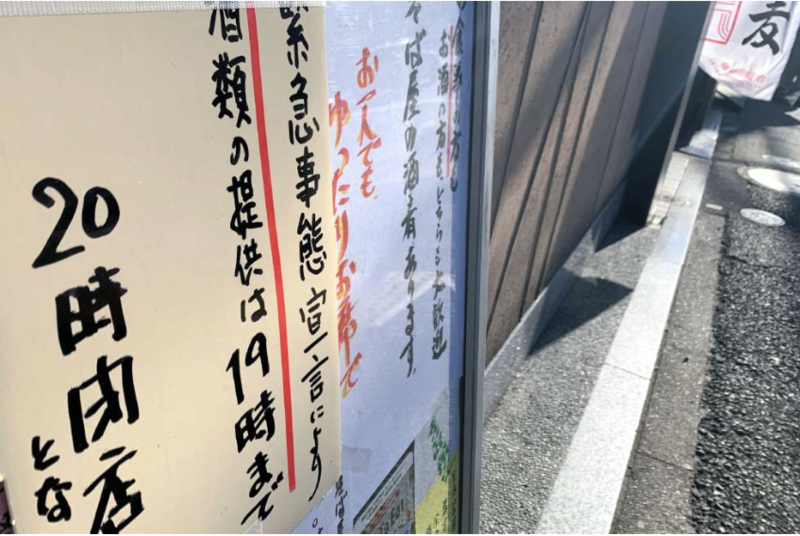

What makes the term interesting is that it constitutes a request for the suppression of desire and constitutionally granted freedoms in the service of a common good which is presumed to be universally shared. Jishuku is constructed as a voluntary act of self-restraint (rather than obedience to the law under threat of punishment). The element of social obligation becomes paramount: the idea of jishuku harnesses the power of social acceptability and social acceptance to do the work of legal sanction. For that reason, the discourse is considered by some to be a suffocating one, and liberals in Japan have a strong aversion to it.14 The voluntary embrace of patterns of behavior (because of social pressure) is particularly troubling to them. Criticism is stifled and resistance made difficult under the presumption of unanimity, shared values, and inner ascent (see Ida 2015; Matsubara 2021; Nishi 2020; Watanabe 1989: 276; Iijima 2021). What has worried some scholars is the way in which, in the case of Covid-19 containment, most restaurants and drinking establishments complied with government requests for shorter hours despite minimal legal enforcement (see Figure 7). They also worried that public opinion seemed to support the government’s message that going out unnecessarily was an anti-social activity (Itō-Morales 2022: 82). And, additionally, Japanese politicians including Abe Shinzō and Finance Minister Aso Taro made statements suggesting that compliance with guidelines could be attributed to a shared ‘culture’ or ingrained social solidarity (Iijima 2021: 285, 293).

Figure 7: Sign posted in the window of an eatery notifying customers that the establishment would close at 8pm and the last order would be at 7pm. Source: Karube et al. 2021. Restrictions on bars and restaurants seemed to be widely obeyed, despite the booming business which these establishments usually do late at night.

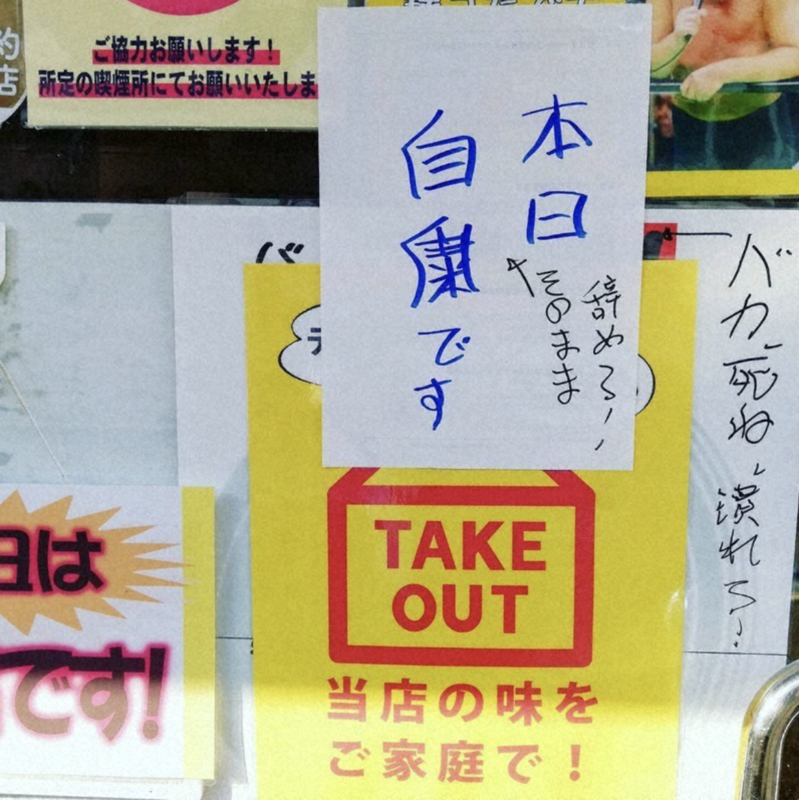

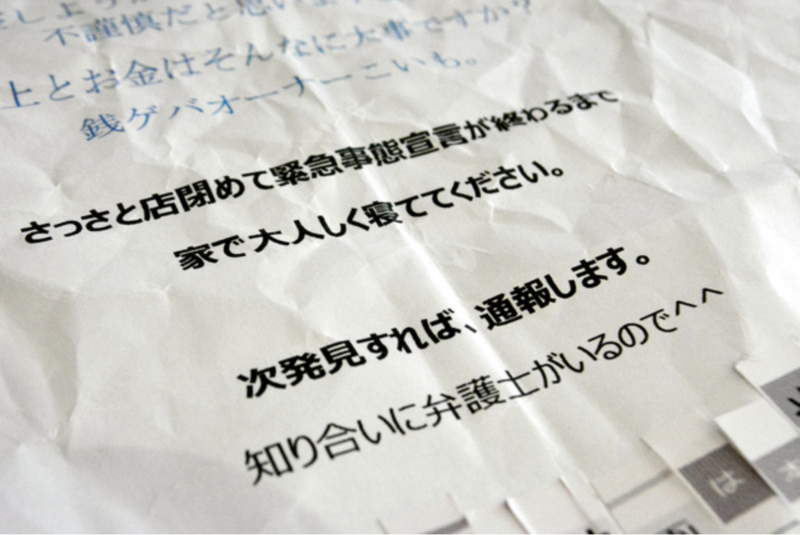

One effect of this appeal to self-restraint and social solidarity was an invitation to citizens to police one another. This was a widely noted phenomenon of vigilante-style policing (policing of social behavior by strangers) and harassment which became known as the ‘jishuku police’ (jishuku keisatsu). The jishuku police were known to undertake private tracking and surveillance of individuals, particularly through social networking sites. They exposed violations of guidelines in the attempt to shame individuals and were known also to make annoying phone calls and engage in other forms of harassment (Itō-Morales 2022). For example, a bentō (lunchbox) shop in Yokohama’s Naka Ward which had remained open for lunch had posted a sign notifying customers they would be closed for a public holiday. On the sign was scrawled, ‘As long as you’re closed, why don’t you go out of business?’ (Yametara? Sono mama) (Suzuki and Shimada 2020a). A beauty parlor in Osaka found a paper posted on the shop door saying: ‘Promptly close your shop. Until the state of emergency is over, stay at home and keep quiet, obediently. I’ll report you if I see this again. I have a friend who’s a lawyer’ (Yamane 2020).

|

|

Figure 8: Left: A vandalized sign at a bentō shop in Yokohama. Another comment reads: ‘Idiot! Die! Go out of business!’ (Baka, shine. Tsuburero!). Right: A sign in a beauty parlor window threatens: ‘Promptly close your shop. Stay home and keep quiet.’ Source: Yamane 2020.

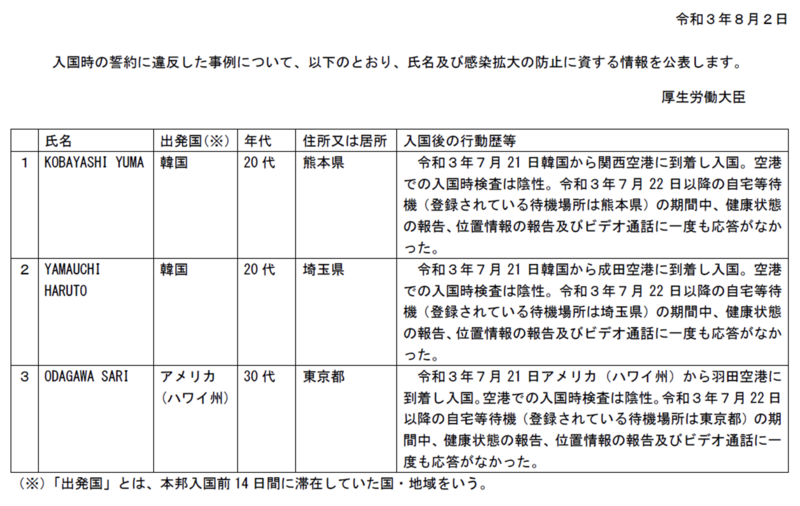

It is interesting to note that the MHLW itself engaged in a culture of peer pressure and ‘naming and shaming’ in order to incentivize compliance with quarantine regulations. Local governments publicly disclosed names of pachinko establishments which did not comply with requests for closure, for example, sanctioning discrimination against certain businesses. The MHLW published on its homepage lists of those who violated quarantine regulations upon entry into Japan by failing to fill out health checks, confirm location, or answer phone or video check-ins. There is no official penalty for these infractions, and it is unlikely those who violated their quarantine agreements were affected by this publicity, but the action deploys social pressure to produce compliance.

Figure 9: A MHLW page (now deleted) that used to publicize names of who entered Japan and violated their self-reporting commitments as a deterrent, in the name of ‘stopping the spread of infection’.

Newspapers reported widely on the stress that individuals experienced as a result of social appearances (seken no me) and the pressure of social surveillance. A public opinion survey conducted by the Asahi Shinbun received a good deal of attention when it found that 67 per cent of respondents agreed at least somewhat with the statement ‘I worry more about social appearances than I do about my own health.’ (Asahi Shinbun 2021).15

By lending legitimacy to the idea that an individual’s own behavior could lead to becoming infected, the moralizing of public health protocols also contributed to discrimination against those who were infected by Covid-19. Containing Covid-19 through informal mechanisms also invited more serious and harmful violations of individual rights, including incidents of defamation and slander (hibō chūshō), discrimination, and scapegoating. It created the possibility of locating blame in individual behavior, everyday choices, with moral character.

Incidences of stranger surveillance, harassment, and discrimination were reported widely in the media. The NHK and local newspapers published testimonials of those who had suffered due to the stigma associated with contracting Covid-19. Health care providers themselves suffered from discrimination and ostracism, as some schools floated the possibility of asking children of health care providers to stay at home (NHK 2020b). A bulletin on the Japan Nursing Association website focusing on reports from the Minamitama hokenshi described the residents’ fear that others in the neighborhood might know about their infection (Kawanishi and Murai 2020b). Nurses appearing at homes in PPE to conduct tests were often turned away, as residents worried neighbors would find out. To address the problem the hokenshi began changing into their PPE in the entryway (genkan). Nurses also consulted with companies on how to report employees’ infections on the company website to minimize stigma and secondary damage (niji higai).16

An article in the Kōbe Shinbun reported the grievances of a wife and daughter in the aftermath of the death of their father and husband, Kōichi Yokono (Kōbe Shinbun NEXT 2020). Yokono was a 72-year-old physicians and former co-director of the Kita-Harima Medical Center. After he died of Covid-19 in April 2020, the family said that he was ‘treated like a criminal’ (hanzaisha atsukai sareta). His wife and daughter were made to feel guilty after the hospital had to close temporarily, and they suffered online slander (fūhyō higai) and abuse, even though Yokono likely became ill while tending to others. Local media named the hospital and publicized that a doctor who was 70 had died, allowing viewers to identify Yokono. Rumors circulated that the man had become infected through engaging in the sex trade or by playing pachinko—statements which re-inscribed discriminatory attitudes towards sex workers and towards the Korean Japanese owners of pachinko parlors. This was despite the fact that Yokono’s death was recognized by the hospital as a workplace injury (kōmu saigai) and the family was compensated through workman’s compensation. The family said that what they read on the internet portrayed Yokono as a ‘virus-spreading killer” (uirusu o baramaku satsujinki). They also experienced other forms of harassment, including phone calls with no voice on the other end.

On the NHK First-person Testimonials webpage, a woman described how she had been unable to tell her relatives of the death of her mother after her mother’s hospitalization (Yamaya 2020). Her mother was taken to the hospital in an ambulance and her condition worsened quickly. She was never allowed to see the body before cremation or to visit the cremation site. Although her mother’s remains were now at her home, she hesitated to tell the neighbors and worried that they might smell the incense burning in the house when they came to collect monthly fees for the neighborhood association. She complained that Covid-19 infection and even death is accompanied by moral judgement: ‘Those who are infected are looked down upon’ (shita ni mite iru), and those who avoid infection are regarded as virtuous (erai).

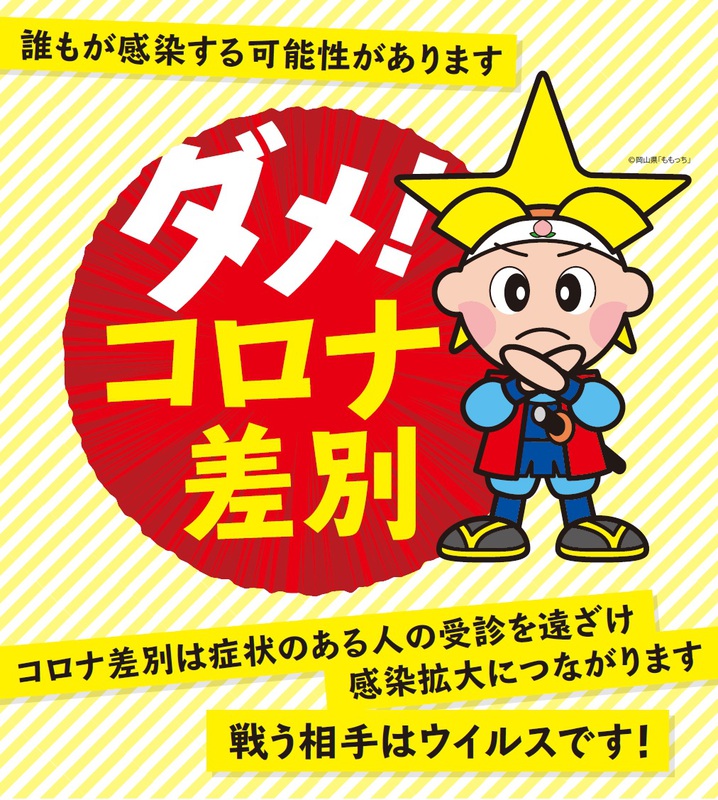

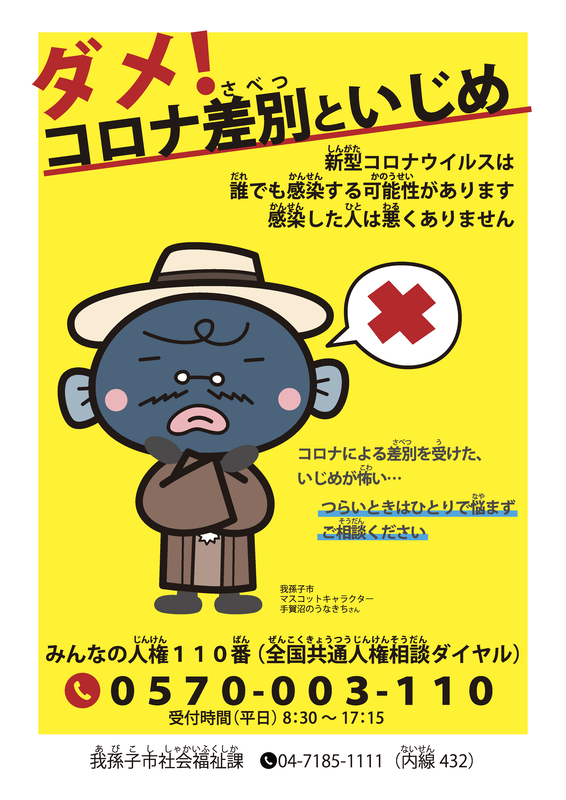

In response to the experience of stigma and harassment, the MHLW, city and prefectural governments, community health experts including the Japan Academy of Public Health Nursing, the Japanese Red Cross Society, and the Ministry of Justice created awareness-raising campaigns to curb Covid-19-related discrimination (korona sabetsu), bullying (ijime), and slander (hibō chūshō).

|

|

Figures 10 and 11: Right: A poster featuring the Abiko city mascot Teganuma no Unakichi-san that reads: ‘NO to discrimination and bullying.’ Source: Abiko City Government website. Left: A poster from Okayama Prefecture featuring its mascot Momocchi warning: ‘Anyone can become infected … . Discrimination discourages those with symptoms from undergoing examination—and can lead to spread of the virus. The opponent is the virus!’ Source: Okayama Prefecture Government website. These posters could be posted in shops, restaurants, and other facilities.

Reports of cars with license plates from outside the prefecture being scratched or drivers harassed led some cities to give out bumper stickers to protect residents who might have different license plates.

Figure 12: A sticker issued by Omachi City in Nagao Prefecture to demonstrate residency, meant to prevent vandalism and harassment. Source: Omachi City Website.

The Japanese Red Cross Society (Nihon Sekijūji) initiated a campaign against harassment, discrimination, and slander, based on their experience in educating populations in poorer nations in resilience and resisting stigma in the face of epidemic.

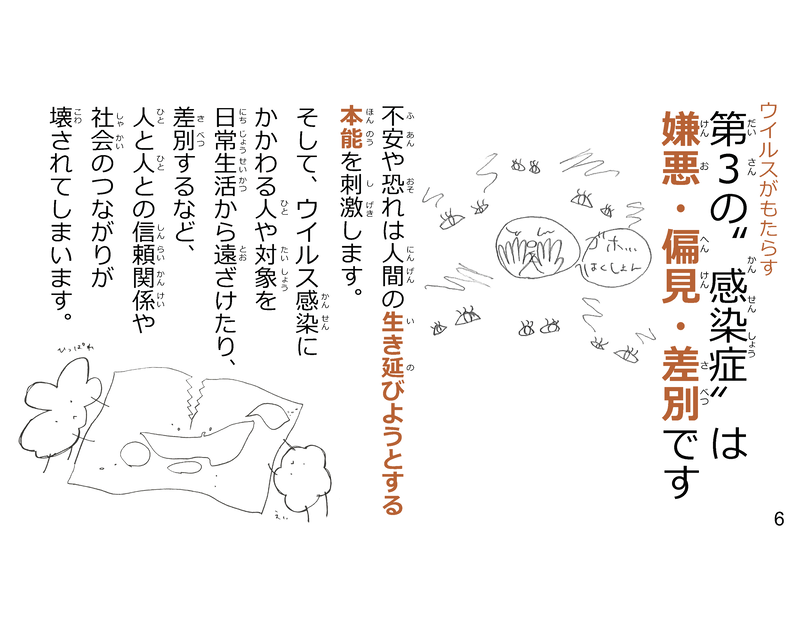

On 26 March 2020, with the virus spreading around the world, the Japanese Red Cross Society published a guide for the general public entitled ‘Let’s Get to Know the Three Faces of Covid-19! How to Stop the Negative Spiral’ (Shin koronauirusu no mitsu no kao o shirō! Fu no supairaru o tachikiru tame ni) (Japanese Red Cross Society 2020a). The book explored how a psychology of blame, alienation, and hate can be born in an environment in which an invisible enemy spreads. Written in simple prose with pencil drawings, the book explores the psychology of blame, suspicion, and fear that containing the virus had given root to. There are ‘three infections’ born of the virus (mittsu no kansenshō), the book begins: ‘illness’ (byōki), ‘anxiety’ (fuan), and ‘hate’ (ken’aku), ‘prejudice’ (henken), or ‘discrimination’ (sabetsu). These infections can slowly (shirazu, shirazu) spread when we are not aware: we direct our suspicion towards an enemy that is more concrete and visible, making them the object of suspicion; we may stigmatize certain geographic areas, certain professions (such as health care providers), certain hospitals, or those who do not wear masks. Hate and rejection might make us feel better temporarily, but we lose track of who is the real enemy (the virus).17

Figure 13: Floating sound bubbles contain the onomatopoetic sound of a cough (goho) or sneeze (hakushon), surrounded by suspicious eyes. To the left, a map of Japan is being torn asunder. Source: Japanese Red Cross Society 2020a.

The book reinforces the importance of community and social unity, social ties (tsunagari), and trust (shinrai kankei). The guide wishes to restore a sense of oneness, so that ‘everyone can come together’ (minna ga hitotsu ni natte) in order to combat the cycle of harm. It is interesting to note here that the ideal of ‘oneness’ is the proposed solution to the problem of fear, while one might also argue that the presumption of oneness and the sanctioning of community control is also a cause of the problem.

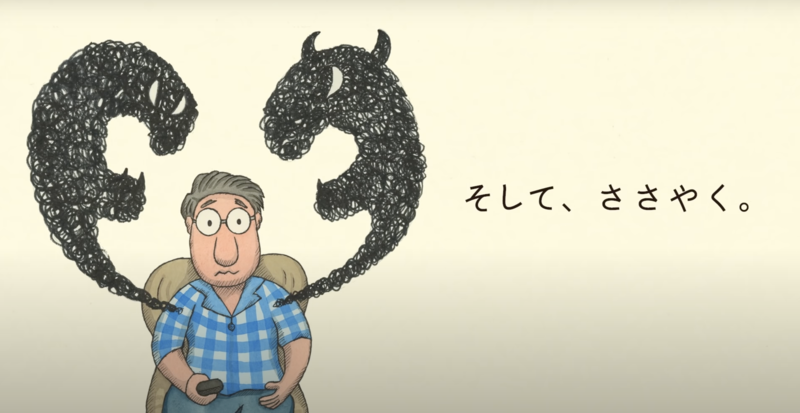

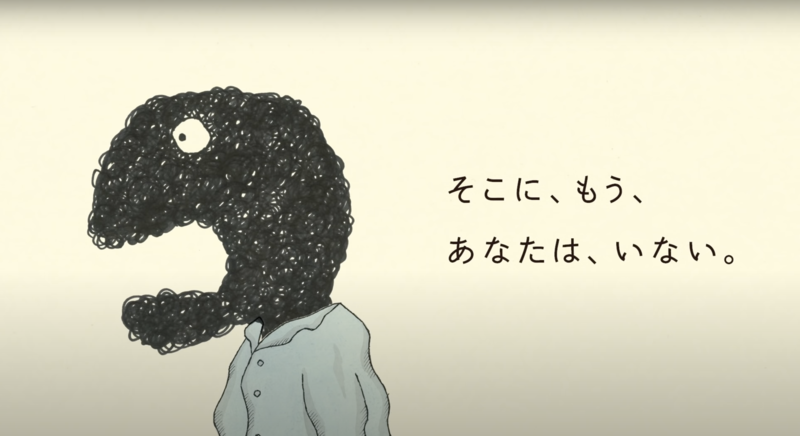

A Japanese Red Cross Society (2020b) video entitled What Comes After the Virus is also a fascinating example of a text which wrestles with the possible harms of self-restraint and social policing. The video begins with a man washing his hands under a stream of water. Handwashing decreases our risk of infection, the film narrates. However, it continues, ‘there is something lurking in our hearts which cannot be washed away.’ The video explores the dark feelings that emerge from fear and anxiety. A floating question mark takes the shape of little gray gremlin (later to become a Godzilla-like monster towering over city buildings). As the protagonist of the video gazes at menacing line graphs on his laptop, he worries, becomes suspicious, watches others as he rides the public transit and wonders who is infectious, who is to blame for another person’s infection, and who is at fault for the whole world arriving at such a situation. As the gray gremlin becomes the protagonist’s head, the film cautions that, before long, ‘When you look in the mirror, the person who is there is no longer you.’

|

|

Figure 14: Stills from the video What Comes After the Virus, released by the Japanese Red Cross Society. Source: Japanese Red Cross Society 2020b.

Although the film is meant to combat prejudice and discrimination, it also has a public health message. Stigma associated with the virus contains its own risks. It may lead people who feel symptomatic to hide their symptoms, allowing the virus to spread even more quickly.

Before the government passed legal amendments to the Act on the Prevention of Infectious Diseases and Medical Care for Patients with Infectious Diseases in January 2021, introducing the possibility of criminal punishment for individuals who refused to participate in an active epidemiological investigation (or who refused hospitalization or left the hospital without official discharge), many health and government organizations, including the Japan Nursing Association (Nihon Kango Kyōkai, which includes hokenshi), the Japanese Society of Public Health (Nihon Kōshū Eisei Gakkai), the Japan Epidemiological Association (Nihon Ekigakukai), and the Japan Association of Public Health Nursing (Nihon Koushuu Eisei Kango Gakkai), and the Japan Federation of Bar Associations, opposed the idea, arguing that criminalizing refusal to participate could discourage sick individuals from testing or seeking care, increase prejudice and discrimination directed towards the sick, and therefore contribute to further spread of the virus.

Conclusion

Japan’s success in containing the pandemic while keeping society ‘open’ has been an object of speculation and envy. And yet the reliance on social mechanisms has had costs, some of which have been morally opprobrious, including discrimination against the infected and scapegoating of specific populations, though this is not unique to Japan.

Japan’s response to the pandemic also revealed a good measure of what we might call public health nationalism and ethnocentrism—a darker side of promoting shared social norms and social order. This was seen clearly in border policies, which, unlike other G7 countries, separated citizens from foreign residents and barred foreign residents from international travel during the initial months of the pandemic, while Japanese citizens were permitted to leave and re-enter—a policy which could not be justified from a public health perspective (Dudden 2020: 56, 58–60).18 In addition, a few scientists took the opportunity to trumpet Japan’s cultural superiority when it comes to hygiene measures or suggest that special cultural or genetic qualities made Japanese people more resilient in the face of the virus.

But few nations emerged as models in the way they handled the pandemic. The power to harness society to impose public health guidelines is at once fearsome, potentially oppressive, and enviable.

A ‘harm reductionist’ approach to public health would urge us to weigh the negative effects of this social control against the costs of policies such as lockdowns (school closures, business closures, work-at-home policies). Lockdowns themselves cause considerable harm—loss of income, social isolation, unemployment, disruption for working parents, poverty, rent foreclosures, homelessness, and crime, as well as health effects including lower childhood vaccination rates, fewer cancer screenings, and other costs associated with the diminished preventative and ‘optional’ health care (Manderson and Wahlberg 2020).

While many called for more extended lockdowns as a measure that would protect everyone, in reality lockdowns protect some more than others. ‘Knowledge workers’ are more likely to be able to work at home than front line and essential workers, who may be more vulnerable to severe disease due to a history of structural inequalities. In fact, lockdowns may disproportionately protect those who are least vulnerable, as with school closures. An analysis of a poll commissioned by The New York Times in January 2022, found that those who supported the most extreme measures to protect the population were not the most vulnerable to severe disease (The New York Times and Morning Consult 2022; Leonhardt 2022).19

Lockdowns became necessary because other forms of social control were impossible to impose or ineffective. In the United States and United Kingdom, some called masking and public health guidelines antithetical to ‘freedom’. Yet the term ‘freedom’ is perversely twisted here and was used to justify actions which might grant ‘freedom’ to one person while compromising the freedom of another. For example, those who refused to wear masks in public spaces compromised the mobility and access to those spaces for the immunocompromised. This idea has been referred to by Elisabeth Anker (2022) as ‘ugly freedoms’. Freedom can also mean the ability to move freely in a society, freedom from disease, and freedom from fear. Social control may paradoxically protect certain individual freedoms, even while it compromises others.

A strong sense of social community and identification with the public good also encourages individuals to abide by public health guidelines. Researchers studying vaccine uptake in the United States among marginalized or lower-income communities found that vaccine uptake depends not merely on understanding ‘the science’ but also on immersion in social community and contact with trusted others who can provide information. While the vaccine roll-out in the United States prioritized speed and efficiency (getting ‘shots in arms’), greater uptake may have occurred if vaccination campaigns had taken advantage of social spheres of trust including peer-led conversations, neighborhoods campaigns, or vaccines provided by trusted authorities such as community health-care providers (Schoch-Spana et al. 2021).

Vaccine hesitancy in the United States reflects the experience of alienation from the common good for many. It is an effect of failing government programs, failing trust in institutions, slashed public health budgets, and structural inequalities resulting in economic segregation (Sreedhar and Gopal 2021). Japan was able to mobilize this sense of public good. At the time of writing in November 2022, 81 per cent of the population is fully vaccinated (Global Change Data Lab, n.d.).

A recounting of Japan’s measures of public health messaging, contact tracing, and informal social control is relevant to the rest of the world, because these measures are rooted not in something unique or ‘cultural’ (an unquestioned aspect of belief and behavior) but rather in policy decisions, the mobilization of society, investments in public health infrastructure, school socialization, and education of all citizens concerning comportment and health consciousness through corporate welfare and universal health care. Even unquestioned mask-wearing cannot be considered a deeply ‘cultural’ phenomenon, as Andrew Gordon (2020) has suggested, since its history is relatively recent in Japan.

Japan’s success allows us to see that controlling such an epidemic poses stark choices. Japanese citizens and residents experienced social pressure, social stress, and informal policing. The measures above are associated with a darker, more coercive side, including the weight of public health paternalism, the pressure of social appearances, and in some instances harassment and bullying.

We also need to remember that not everyone faired equally well in the pandemic. Women suffered disproportionately, with higher reported incidences of domestic violence, as well as economic effects of job loss and coping with additional burdens at home (Gender Equality Bureau Cabinet Office 2021). Technical interns, a long-exploited underclass of industrial immigrant workers, suffered from the pressure to continue working ‘as if nothing had happened’, while receiving limited Covid-19-related social supports, as did others who faced precarity (Tran 2020; Slater 2020; Slater and Barbaran 2020; Tanaka 2020).

Yet in the United States and United Kingdom, two of the world’s wealthiest nations, citizens witnessed the highest case numbers and excess mortality in the world. Even as scientific knowledge circulated globally about prevention, these societies were ill-prepared to act on it.

What is the right balance between communitarian focus on the common good and guarantee of individual rights? How much social pressure is warranted to contain the infection? The pandemic has pushed scholars to return to these questions (see Itō-Morales 2022). Japan’s experience allows us to see the possibilities of society as perhaps one of the most effective tools we have in addressing epidemic disease. At the same time, it reminds us not to be romantic about the ideal of community or a shared common good. Perhaps other societies would not have accepted the trade-offs that Japanese citizens and residents have lived with during the pandemic. However, in not doing so, they paid a high price of failing to contain the spread of infection or succumbing to more centralized forms of social surveillance and control with their own costs.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to Peter Cave, Kimberly Hassel, Michiru Lowe, Jonathan Morduch, Ryō Morimoto, Michael Solomon, David Slater, and Sarah Strugnell for helpful comments and to Michiru Lowe and Leon Morduch for research assistance. A panel discussion with Andrew Gordon and Karen Thornber at the Harvard University Weatherhead Center for International Affairs, Program on U.S.-Japan Relations, moderated by Christina Davis and coordinated by Shin Fujihira, helped shape the ideas.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Cumulative COVID-19 Cases (per million)

Source: Our World in Data, Coronavirus (COVID-19) Cases

(https://ourworldindata.org/covid-cases)

Click to expand.

Appendix 2: Cumulative COVID-19 Deaths (per million)

Source: Our World in Data, Coronavirus (COVID-19) Deaths

(https://ourworldindata.org/covid-deaths)

Click to expand.

| Appendix 3: School Closures |

Key

0 = no measures

1 = recommended

2 = recommended (only at some levels)

3 = required (all levels)Source: Our World in Data, COVID 19: School and Workplace Closures (https://ourworldindata.org/covid-school-workplace-closures)

| Appendix 4: Work Closures: |

Key

0 = no measures

1 = recommended

2 = required for some

3 = required for all but key workersSource: Our World in Data, COVID 19: School And Workplace Closures (https://ourworldindata.org/covid-school-workplace-closures)

| Appendix 5: Stay-at-Home Restrictions |

Key

0 = no measures

1 = recommended

2 = required (except essentials)

3 = required (few exceptions) Source: Our World in Data, COVID 19: Stay-at-Home Restrictions (https://ourworldindata.org/covid-stay-home-restrictions)

| Appendix 6: Cancellation of Public Events |

Key

0 = no measures

1 = recommended cancellations

2 = required cancellationsSource: Our World in Data, COVID 19: Cancellation of Public Events and Gatherings (https://ourworldindata.org/covid-cancel-public-events)

| Appendix 7: Face Coverings |

Key

0 = no policy

1 = recommended

2 = required in some public spaces

3 = required in all public places

4 = required outside-the-home at all timesSource: Our World in Data, COVID 19: Face Coverings (https://ourworldindata.org/covid-face-coverings)

References

@__Aerials. 2020. Tweet, 28 February. twitter.com/__aerials/status/1233280600640872448.

Abe, Marié. 2016. ‘Sounding against Nuclear Power in Post-3.11 Japan: Resonances of Silence and Chindon-ya.’ Ethnomusicology 60(2): 233–62.

Adams, Vincanne, Dominique Behague, Carlo Caduff, Ilana Löwy, and Francisco Ortega. 2019. ‘Re-imagining Global Health through Social Medicine.’ Global Public Health 14(10): 1383–1400.

Alexy, Allison. 2020. Intimate Disconnections: Divorce and the Romance of Independence in Contemoprary Japan. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Allison, Anne. 1994. Nightwork: Sexuality, Pleasure, and Corporate Masculinity in a Tokyo Hostess Club. Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press.

Andō, Rei. 2020. ‘Domestic Violence and Japan’s Coronavirus Pandemic.’ The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus 18(18), no. 7. apjjf.org/2020/18/Ando.html.

Anker, Elisabeth. 2022. ‘The Exploitation of “Freedom” in America.’ The New York Times, 4 February. www.nytimes.com/2022/02/04/opinion/ugly-freedom-discrimination-racism-sexism.html.

Appadurai, Arjun. 2020. ‘The COVID Exception.’ Social Anthropology 28(2): 221–22.

Ara, Tadashi. 2021. ‘COVID-19: Statement Opposing the Bills to Amend the Infectious Diseases Act and the Special Measures Act.’ Japan Federation of Bar Associations website, 22 January. www.nichibenren.or.jp/en/document/statements/210122_2.html.

Asahi Shinbun. 1939. ‘Tegaru na yuiage: jishuku no natsu no kami [An Easy Bun: Restrained Summer Hair.’ Asahi Shinbun, 27 July.

Asahi Shinbun. 1939. ‘Koua no haru, Ima ranman wa migoro, jishuku hanami wa ok [In the Spring of Greater East Asia, a Restrained Flower-Viewing Is Ok When the Cherries Are in Full Bloom].’ Asahi Shinbun, 9 April.

Asahi Shinbun. 2021. ‘Korona kansen “kenkō yori seken no me ga shinpai” 67%: yoron chōsa [Covid-19 Infection. 67 Per Cent Reply: “I Worry More About Social Appearances than I Do about Getting Infected” According to a Public Opinion Survey].’ Asahi Shinbun, 10 January. www.asahi.com/articles/ASP196RLJNDPUZPS002.html.

Karube, Rihito, Chiaki Hagiwara, Yūsuke Nagano, Momoko Ikegami, and Yūki Okado. 2021. ‘Iryō kiki Korona Tokyo 100 days [Healthcare Crisis, Covid-19 Tokyo: 100 Days].’ Asahi Shimbun Digital Premium A, no. 13, 10 February. www.asahi.com/special/coronavirus/tokyo-100days-3rd.

Bartzokas, Nick, Mika Gröndahl, Karthik Patanjali, Miles Peyton, Bedel Saget, and Umi Syam. 2021. ‘Why Opening Windows is a Key to Reopening Schools.’ The New York Times, 26 February. www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/02/26/science/reopen-schools-safety-ventilation.html.

Borovoy, Amy and Christina A. Roberto. 2015. ‘Japanese and American Public Health Approaches to Preventing Population Weight Gain: A Role for Paternalism?’ Social Science & Medicine 143: 62–70.

Borovoy, Amy. 2017. ‘Japan’s Public Health Paradigm: Governmentality and the Containment of Harmful Behavior.’ Medical Anthropology 36(1): 32–46.

Borovoy, Amy. 2005. The Too-Good Wife: Alcohol, Codependence, and the Politics of Nurturance in Postwar Japan. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Cabinet Secretariat Government of Japan Office for Covid-19 and Other Emerging Infectious Diseases Control. 2021. ‘Kinkyū jitai sengen o fumaeta shiensaku [Support Policies Under the Declaration of a State of Emergency].’ Cabinet Secretariat Covid-19 Infectious Diseases Control, 3 February. corona.go.jp/action/pdf/shiensaku_20210203.pdf.

Cave, Peter. 2016. Schooling Selves: Autonomy, Interdependence, and Reform in Japanese Junior High Education. Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press.

Cave, Peter. 2004. ‘“Bukatsudō”: The Educational Role of Japanese School Clubs.’ Journal of Japanese Studies 30(2): 383–415.

Cohen, Roger. 2021. ‘The Entangling, Ever-Extending Labyrinth of French Lockdowns.’ The New York Times, 26 April. www.nytimes.com/2021/04/26/world/europe/france-covid-lockdowns.html.

Colgrove, James, Gerald Markowitz, and David Rosner. 2008. The Contested Boundaries of American Public Health. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

DJ Barusu. 2020. Koike Yuriko chiji “mitsu EDM” #DJ Barusu [Governor Yuriko Koike “Social Distance EDM”]. YouTube, 21 April. www.youtube.com/watch?v=5H5TejYDkTQ.

Dooley, Ben. 2020. ‘Japan’s Locked Borders Shake the Trust of Its Foreign Workers.’ The New York Times, 5 August. www.nytimes.com/2020/08/05/business/japan-entry-ban-coronavirus.html.

Dudden, Alexis. 2020. ‘Masks, Science, and Being Foreign: Japan During the Initial Phase of Covid-19.’ The Pandemic: Perspectives on Asia, edited by Vinayak Chaturvedi. Ann Arbor, MI: Association for Asian Studies.

Emanuel, Ezekiel, Ross E.G. Upshur, and Maxwell Smith. 2022. ‘What Covid Has Taught the World about Ethics.’ New England Journal of Medicine 387(17): 1542–45.

Farrer, James. 2020. ‘How Are Tokyo’s Independent Restauranteurs Surviving the Pandemic?’ The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus 18(18), no. 13. apjjf.org/2020/18/Farrer.html.

Feldman, Eric. 2001. ‘The Landscape of Japanese Tobacco Policy: Law, Smoking and Social Change.’ The American Journal of Comparative Law 49(4): 679–706.

Garon, Sheldon. 1997. Molding Japanese Minds: The State in Everyday Life. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.