Abstract: This paper examines the little-known and long forgotten overseas deployment of Japanese minesweepers to North Korea in 1950 and the events that led to postwar Japan’s only known deployment to a combat zone that led to the loss of Japanese life.

Keywords: Korean War, Minesweeping, Japanese Self-Defense Forces, desertion

Minesweeping in Early Postwar Japan

This paper examines the little-known deployment of Japanese minesweepers in the service of United Nations maritime operations during the Korean War. In October 1950, the Japanese government under direct pressure from the United States Navy (USN) ordered sailors of the Maritime Safety Agency (MSA), the precursor to the Maritime Self Defense Force (MSDF), to clear mines off the coasts of North and South Korea. As part of this operation one of a number of MSA squadrons was deployed to a live combat zone off the North Korean port of Wonsan. For many sailors and officers alike, their mission provoked enormous disgruntlement and fears of participating in an unconstitutional military deployment that would place them in an active combat zone. Despite reassurances that they would not be subject to combat, their fears proved to be valid. The MSA’s deployment to Wonsan resulted in the loss of Japanese life due to enemy action – the only known instance of Japanese citizens in government service dying in a warzone in the postwar era. To this day, the details of the MSA’s deployment to Wonsan as well as other parts of the Korean peninsula remain largely unknown by Japan’s public due to deliberate obfuscation by the Japanese government.1 The details of the MSA’s deployment to Wonsan and the experiences of MSA sailors offer a disturbing account of how one group of Japanese citizens found themselves heading back to war just five years after Japan’s defeat in 1945.

Japan’s participation in Korean War naval operations was rooted in the incomplete demobilization of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) during the early stages of the occupation of Japan. At the start of the Allied occupation, tens of thousands of Japanese and Allied mines threatened Japanese ports, coastlines, and key shipping channels.2 Between 1945 and 1953, some 90 vessels sank due to mines, at times only a few hundred feet from Japan’s shore. In total, postwar collisions with mines accounted for 2,294 killed and 424 injured in these years.3

By the war’s end, the IJN had placed 55,347 mines around the Japanese coastline to hinder Allied invasion efforts. In addition, US Navy submarines and airplanes had dropped 6,546 motion detector mines in key shipping channels and ports in order to interdict Japanese shipping.4 Indicative of how seriously the Allies took the threat of these mines, on September 2, 1945, the Occupation issued General Order Number 1, which, in addition to calling for the dissolution of the Imperial Japanese military, ordered the Japanese government to retain capabilities for clearing mines around the Japanese home isles.

Responsible Japanese or Japanese-controlled Military and Civil authorities will insure that: (a) All Japanese mines, minefields, and other obstacles to movement by land, sea, and air, wherever located, be removed according to instructions of the Supreme Commander for Allied Powers…5

This was followed by the Supreme Commander for Allied Powers Instruction Note (SCAPIN) Order Number 2 on September 3, 1945, which included instructions for the Japanese government to take charge of all minesweeping duties in Japanese and Korean waters.6

The Japanese Imperial General Headquarters will insure that all minesweeping vessels immediately carry out prescribed measures of disarmament, fuel as necessary and remain available for minesweeping service. Submarine mines in Japanese and Korean waters will be swept as directed by designated Naval Representatives of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers.7

Execution of the Occupation’s orders for clearing mines necessitated the retention of IJN sailors and officers. This was not particularly unusual under the framework for the then ongoing demobilization of the IJN. Japan’s Navy Ministry oversaw the demobilization of all IJN personnel.8 By the time of its dissolution in December 1945, the Navy Ministry demobilized the vast majority of IJN personnel within Japan. However, many sailors stationed abroad at war’s end were not demobilized prior to their repatriation to Japan. Due to the need to repatriate overseas Japanese soldiers and sailors to Japan from across Asia and the Pacific, the Navy Ministry delayed the demobilization of thousands of IJN personnel in order to crew transports provided by the USN and specially disarmed Japanese warships converted into ad hoc transport vessels between 1945 and 1947.9 Critically, whereas the IJN personnel who crewed repatriation ships were ultimately demobilized, IJN personnel assigned to postwar minesweeping duties never underwent any form of proper demobilization, instead becoming the nucleus of Japan’s future MSDF.

On September 16, 1945, the Japanese government established the Minesweeping Bureau in the Navy Ministry’s Military Affairs Office. This was followed by the creation of six regional commands that oversaw a force of 10,000 IJN sailors and 385 minesweeping vessels of varying types.10 Commanding minesweeping operations were mine warfare specialist, Captain Tamura Kyūzō, and 713 other IJN officers who were granted special protection from the Occupation’s purge of military officers from public service in 1946.11 At a time when Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) and IJN officers underwent demobilization or were purged from public service, the Minesweeping Bureau provided a rare refuge for these officers and enlisted men.

Sources are unclear as to precisely why the Allied Occupation government and the USN did not take direct control of postwar mine clearing operations. However, it is possible to surmise why the Occupation chose to rely on Japanese personnel for minesweeping duties in Japanese waters. Mine sweeping is a laborious, time consuming, and above all, dangerous task. Many Japanese sailors lost their lives after the war clearing mines. Moreover, it was assumed that the IJN had the best information on the location of many mines in Japan’s vast waterways. Moreover, following Japan’s surrender, American tolerance for further casualties all but evaporated, while families of service members along with active service members waged a campaign calling for immediate demobilization. The Occupation’s decision to order Japanese sailors to engage in minesweeping was both an expedient decision to save American lives from dangerous work and acquiescence to demands for demobilization by American voters and service members.

In 1948, Japan’s Minesweeping Bureau was significantly reduced in size to just 1,508 personnel and 53 boats when it was placed under the control of the Maritime Safety Agency (MSA), the predecessor to Japan’s MSDF. Tamura remained the head of minesweeping operations, while his personnel were still mainly former IJN sailors.12 By 1950, after nearly five years of clearing Japan’s waterways, Tamura and his crews were arguably the most experienced minesweepers in the Western Pacific.13 This fact would not escape the attention of the USN in the early months of the Korean War.

“Please Keep It Secret”

On June 25, 1950, North Korean soldiers and tanks crossed the 38th parallel into South Korea. Despite more than a year of cross border skirmishes between both Koreas, North Korea’s invasion caught both the South Korean and American governments by surprise. Within days, South Korean forces were either surrounded or in headlong retreat. The ability of South Korean soldiers to fight was severely undermined by poor training and the lack of effective antitank weaponry By July 1950, North Korean forces surrounded South Korean forces along with a growing number of American and United Nations’ units in a “pocket” bordered by the Nakdong river to the north and the port city of Busan to its south. At the brink of defeat, South Korean and American forces successfully mounted a defense that staved off collapse. Exploiting the North Korean military’s exhaustion, South Korean and UN forces went on the offensive. On September 15, 1950, US Marines landed at the port of Incheon, and rapidly advanced on Seoul. Alongside US and South Korean personnel, Japanese merchant marine sailors also participated in the Incheon operations in the capacity of ferrying and landing US Marines on Incheon’s beaches. In some cases, Japanese sailors witnessed combat between US and North Korean forces.14 However, no Japanese personnel participated in sweeping Incheon Bay of mines in September 1950. Concurrent with the Incheon landings, South Korean and UN forces broke out from the Busan pocket and rapidly advanced up the Korean peninsula. By the beginning of autumn 1950 North Korean forces were in full flight – once more crossing the 38th parallel, but now in reverse.

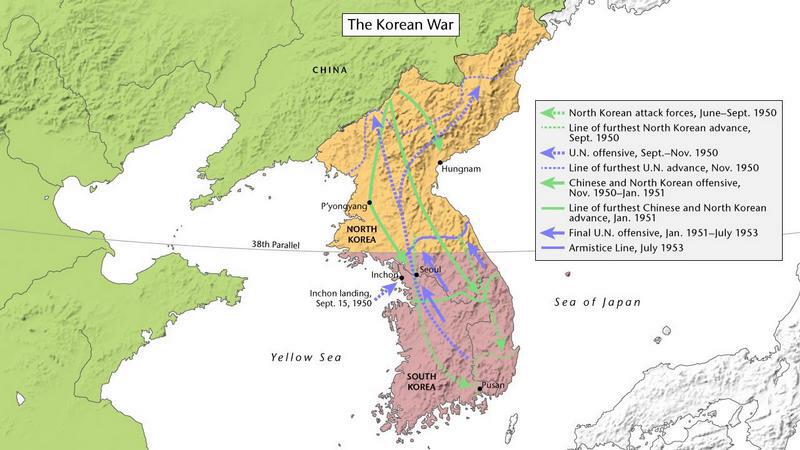

Figure 1: Map showing major advances by both UN and Communist forces during the Korean War. Map of South Korea. Image from PBS.

With the North Korean military in full retreat, American and UN forces began planning for an amphibious landing in October at Wonsan, a city on North Korea’s eastern coast. This operation required significant minesweeping capabilities, which UN forces lacked in theater. In 1946, the USN had transferred its minesweeping force from Japan to California, rendering it too far away to be of much use. By the autumn of 1950, the USN had managed to only redeploy ten minesweepers to the vicinity of the Korean peninsula.15 By comparison, the USN possessed just 12 minesweepers in the entire far east.16

USN Vice Admiral Arleigh Burke, commander of USN operations in Korea, was deeply troubled by the shortage of minesweepers for Wonsan and subsequent operations. Burke was aware that at the time Japan’s MSA possessed 79 minesweepers, making it the largest force of its kind in the Pacific.17 Burke was determined to secure Japanese minesweepers for the Wonsan operation, and so unilaterally decided to speak with the Japanese government about releasing MSA vessels for use in Korean waters.18 Stunningly, Burke had not received permission for his scheme. According to Burke, he deliberately did not inform the USN, General Douglas MacArthur, the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers in Japan, or the US Department of State about his conversations with the Japanese government.19 Only after securing the Japanese government’s consent, described in the following pages, did Burke obtain MacArthur’s retroactive approval for Japanese participation in naval minesweeping operations in the Korean War. Burke later justified his actions by claiming that he believed either MacArthur or the US government would have rejected Japanese involvement in US naval operations if he had followed the correct chain of command for implementing his plan.20

On October 2, 1950 Burke invited Ōkubo Takeo, head of the MSA, to meet at his headquarters.21 Burke took Ōkubo on a personal tour, showing him one large map after another hanging from his headquarters’ walls displaying classified information on unit dispositions and the overall war situation. After explaining that North Korean mines had stymied UN amphibious operations, Burke turned to Ōkubo and asked the MSA for help. “Japan’s minesweeping force is superb; I have deep faith in it.”22 To Burke’s surprise, Ōkubo rejected his demand for use of the MSA in Korea. Citing Japan’s constitution and the South Korean chain of command, Ōkubo responded, “I am afraid I cannot do that. From the standpoint of [Japan’s] constitution, it is not permissible, and, moreover, I lack the authority.” Burke found Ōkubo’s refusal particularly grating.23 Yet, Ōkubo had solid ground for refusing Burke’s extraordinary request.

Figure 2: An undated photo of Tamura (center) and Ōkubo (right) taken presumably several decades after the Korean War. Chōsen dōran tokubetsu sōkaitai-shi (Tokyo: Sewajinkai, 2009), 14.

Under Article 9 of Japan’s postwar constitution, Japan was prohibited from participating in an overseas war or maintaining an official military. Since Ōkubo well understood the fact that Korea was an active warzone, he could not personally authorize the deployment of personnel to Korean waters.24 Most importantly, however, was the issue of the MSA’s official status. Article 25 of the MSA Law was unambiguous about the MSA’s status as a non-military entity. The law stated: “Nothing in this act shall be construed as authorizing the Maritime Safety Agency or its personnel to be organized or trained as a military force or perform military functions.”25 Article 25 of the MSA Law, therefore, left little room for interpretation by Ōkubo. Recognizing this fact, Ōkubo would later recall for the author of a 1981 book on Japan’s rearmament: “It [amounted] to participation in a war. The issue was serious, but it was not a problem that could be decided by just me.”26 The person who could decide this matter was Prime Minister Yoshida Shigeru.

It is at this point that the chronology of events becomes slightly muddled. Both Ōkubo and Burke arranged separate meetings with Yoshida to discuss the MSA’s potential deployment to Korean waters. However, it is not altogether clear who met first with Yoshida following the Burke-Ōkubo October 2 meeting.27 I am inclined to believe that Yoshida met with Ōkubo first, since Burke’s recollections depict a Yoshida who seemed reluctant and in need of some convincing before consenting to Burke’s request.28 It is also once more worth reflecting on the fact that Burke at no point possessed the authority to negotiate with Ōkubo or Yoshida. Whether Ōkubo and Yoshida understood Burke to be acting in an autonomous capacity or they believed he spoke on behalf of MacArthur, or the US government is unclear.

Following his meeting, Ōkubo met with Yoshida to receive further guidance on how to respond to Burke’s request. To Ōkubo’s surprise, Yoshida reversed his position on aiding UN forces in Korea. “I have said that cooperating with the UN forces is the primary policy of the Japanese government,” Yoshida instructed Ōkubo to comply with Burke’s request. “…Because it is an extremely delicate time, go for it.” Yoshida then warned Ōkubo: “This, Ōkubo, is top secret. Please keep it a secret.”29 Yoshida was well aware of the political backlash which would have emerged if his decision were to be known by opposition politicians or the Japanese public.

Why was Yoshida willing to deploy the MSA to help USN military operations in Korean waters despite Japan’s Constitutional position of non-intervention? Above all, Yoshida would have been unwilling to jeopardize ongoing negotiations for a peace treaty that he hoped would end the occupation and restore Japanese sovereignty.30 This was the background to the MSA’s deployment as well as subsequent forms of assistance Japan rendered to the UN’s war effort.

Since the start of the Korean War, Yoshida had come under constant pressure from the US to provide direct and indirect aid to the UN-US forces. Unknown to the Japanese public at the time, as early as June 1950, Yoshida provided extensive non-military aid to the UN’s war effort.31 This aid took two different forms. On the domestic front, Yoshida provided significant aid in the shape of opening military bases, railroads, and ports for rear area logistical support of the war. Japan provided additional support through manufacturing of weapons, vehicles, and other highly sought-after items thereby reducing the need to rely on shipping from the US mainland. More relevant for the MSA’s deployment, however, was Yoshida’s agreement in June 1950 to make available 138 Japanese merchant marine vessels and 7,550 sailors to ferry UN soldiers and military supplies to and from the Korean peninsula.32 This represented a significant and tangible form of direct intervention in the war. Placed alongside the deployment of Japanese merchant marine vessels and sailors, the MSA’s deployment appears to have been part of a broader policy to render maritime support to the UN’s war in Korea.

But Yoshida did not comply with all US requests for assistance for the war effort. Most notably, just a few months before his meeting with Burke, Yoshida had resisted American pressure to dispatch Japan’s newly established Keiretsu Yobitai (National Police Reserve) to the Korean peninsula on constitutional grounds. Furthermore, Yoshida was adamant that Japan not become involved in the ground war on the Korean peninsula and risk its postwar economic recovery. Yet, Yoshida’s willingness to provide maritime support to the USN’s efforts suggests he believed the rewards of rendering assistance outweighed any risks of becoming more deeply involved in the war in Korea. Of course, the question remains: why was Yoshida willing to risk the lives of Japanese citizens at sea but not on land?

Like the mobilization of merchant marine vessels, Yoshida may have seen the MSA as a convenient and relatively safe option for providing direct assistance to the UN war effort. Because the MSA would engage in clearing mines from waterways, Japanese sailors would theoretically not encounter North Korean soldiers. The MSA’s maritime operations also had an additional benefit. In the event that a Japanese vessel was sunk, or Japanese citizens were killed or wounded, the Japanese government could maintain plausible deniability since said incident would occur at sea far from the eyes of the Japanese public and the media. This perhaps allowed Yoshida to feel confident about his ability to control access to information about the MSA’s operations and maintain the fiction of indirect assistance to the UN’s war effort.

After meeting with Yoshida, Ōkubo insisted on having written orders issued specifically by the US Occupation that provided legal cover for the deployment of Japanese minesweepers outside Japanese territorial waters. On October 4, 1950, Ōkubo received the orders he had asked for.33 The US Occupation authorities reissued the previously quoted General Order No. 1 and section 13 of SCAPIN Order No. 2.

Section 13 of SCAPIN Order No. 2 specified that Japanese minesweepers would operate in “Japanese and Korean waters.” This order was issued just weeks after Japan’s surrender when Japan remained largely in control of southern Korea and thousands of Japanese and Allied mines cluttered Korean waterways. In 1950, Japan’s Imperial General Headquarters had long since been disbanded and most of Japan’s naval personnel released. But the anachronistic nature of the order was irrelevant. It provided the desired pretext for MSA vessels to resume minesweeping in Korean waters without having to specifically state that their real purpose was the clearance of North Korean mines, not leftover World War II era mines. The reissuing of SCAPIN Order No. 2 may have dispelled any lingering qualms Ōkubo harbored about the legality of the MSA’s upcoming mission. For the sailors and officers of the MSA, however, the task of persuading them of the legality and legitimacy of their mission would prove to be far more rancorous.

“We Will Not Cross the 38th Parallel.”

Coinciding with the issuance of SCAPIN Order No. 2, on October 4, 1950, USN Vice Admiral Turner Joy, Commander, Naval Forces Far East, ordered the immediate mobilization of MSA minesweepers for unspecified duties.

The Japanese Government is hereby directed to assemble twenty (20) Japanese Minesweepers [Sic], one guinea pig, and four other Japanese Maritime Safety vessel [Sic] in Moji as soon as practicable. These vessels will be prepared for such minesweeping operations as will be designated in future directives.34

Not long after Joy ordered the MSA’s mobilization, MSA captains and crews in the Inland Sea region received orders to immediately prepare for duty. These orders took MSA officers and sailors alike by complete surprise. Before October 4, there had been no indication that a mission of any significance, let alone a deployment to Korean waters, was imminent. Unaware of the reason for their mobilization, MSA vessels hastily departed for the arranged rendezvous. By October 5, all twenty MSA vessels had reached their assembly point and anchored off the town of Karato near the port of Shimonoseki (Joy’s orders called for MSA vessels to meet at Moji, but Japanese firsthand accounts indicate that the vessels ultimately gathered at Karato in Yamaguchi prefecture instead).35

Figure 3: Picture showing a typical MSA minesweeper (left) and patrol boat (right). These boats comprised most vessels deployed by the MSA in Korean waters. Chōsen dōran tokubetsu sōkaitai-shi (Tokyo: Sewajinkai, 2009), 14.

Anxiety and confusion reigned among the MSA crews at Karato. Everyone wanted to know why they were there given that they had received no information about their mission. Seeking to suppress the growing tension, the Director-General of the MSA’s minesweeping force, Tamura Kyūzō, hosted a meeting on October 6 for his fellow captains and staff officers in the wardroom aboard his flagship, Yūchidori. Ōkubo was also in attendance, perhaps as a show of support for Tamura’s leadership. Tamura began the meeting by revealing to the assembled officers the purpose for their mobilization. After relating Joy’s original orders, Tamura divulged that the Occupation authorities had issued another pair of orders to the Japanese Ministry of Transportation, which oversaw the MSA. These read in part, “The Japanese government as much as possible will newly organize a minesweeping force comprised of minesweepers and place them under the command of USN officers presently in Korean territorial waters.”36 Tamura further revealed that Joy had personally issued yet another set of orders dictating the organization of the Japanese minesweeping force. “The Japanese minesweeper force will fly the international “E” flag (used by commercial shipping) instead of the Japanese flag.”37 Additionally, Tamura related that the Japanese vessels would be redesignated Force 66, under the command of the US 7th Fleet.38 Tellingly, Tamura left out several key details of his orders. To the consternation of those listening, he said nothing about where in Korean waters MSA vessels might operate, for how long, and what might happen if any Japanese sailor was wounded or killed. As the briefing came to an end, a stunned silence fell over the wardroom.

A valuable witness to the subsequent debate and deployment of the MSA was deputy commander Tajiri Shōji, the head of the largest minesweeping contingent based out of the port of Kure.39 Tajiri was struck by his colleagues’ shock and dismay in response to Tamura’s presentation. “Everyone was skeptical of the Director-General’s (Tamura) explanation. But not a single person asked a question.”40 No longer able to stand the silence, Tajiri pressed Tamura for more answers.41

Director-General! What is our real mission? What is our destination? What is the basis for our actions? Overseas, what will our status be if we are placed under command of the US military? In case of emergency, what kind of compensation will there be?…42

Tamura offered no substantive answer to these questions. “Not one clear answer escaped the director general’s mouth,” recalled Tajiri. Adding further, “a strange air began to float among the [meeting’s] attendees, and then a [palpable sense of] malaise and doubts suddenly exploded from the bottom of [everyone’s] hearts!”43

Like Tajiri, many of the other captains wanted to know the real reason for and status of their deployment. One after another, they peppered Tamura with questions and demanded specific details on the parameters and nature of their mission. Yet another eyewitness to these events was Captain Nose Shōgo, a former commander in the IJN and second most senior officer present at the meeting.44 Nose recorded some of these comments as well as Tamura’s responses in an essay years after the Korean War. His recollections reveal the intensity of the debate. One anonymous captain asked, “In which sea will we be clearing mines?” Another followed up: “If we are placed under the command of the US Navy commander in Korea, doesn’t this mean we will be forced to participate in the Korean War? If so, isn’t that unconstitutional?” Yet another, seeking reassurances they would not enter North Korean waters inquired: “Will we cross the 38th parallel? Will we not cross it? If we cross it, we cannot participate.”45

Seeking to suppress the mistrust and anxiety among his subordinates, Tamura replied: “You will not enter hazardous operational areas. We have an agreement with the US Far East Military Headquarters that you will only conduct minesweeping in safe places.”46 At this point, few if any of the assembled captains were willing to accept Tamura’s reassurances as it became increasingly clear that their mission was in a war zone with no clear limits and dubious legality.

A new wave of questions followed Tamura’s remarks. “What will you do if that is not the case?” demanded an irate captain. Imagining the potential risk to life a deployment might involve, another captain added, “What will you do if an unthinkable accident occurs?”47 The meeting continued in this fashion for two long hours. By the meeting’s end, many questions remained unanswered. Tajiri notes that it was unclear whether Japanese or US officers would take responsibility for what occurred during the MSA’s deployment. More troubling, if Japanese vessels did not sail under the Japanese flag, then what exactly would their status be? Were the sailors temporarily no longer Japanese citizens, but stateless contractors in the employ of the US Navy? Tamura could not answer these questions.48

Up until this point Ōkubo had sat through the meeting in silence. He then provided the gathered officers their only explanation of the mission’s political justification. “For the sake of Japan’s independence, we must overcome this challenge and [make an international contribution].” Seeking to play up the stakes of the MSA’s deployment, Ōkubo concluded: I believe that later generations of Japanese looking back on history will surely appreciate your actions.”49 Finally, the MSA sailors received an official justification for the MSA’s deployment. Vague references to fighting for Japan’s independence from occupation and histrionic allusions to winning the praise of future Japanese generations were the only reassurances they received. To what extent Ōkubo’s words resonated with the assembled officers is impossible to ascertain. Notably, neither Tajiri nor Nose mention Ōkubo’s comments in their accounts. Ōkubo, who also wrote an account of this meeting, devoted a single sentence to the events and did not record his own words. It is therefore tempting to conclude few if any MSA personnel found Ōkubo’s speech particularly memorable.

Before the meeting concluded, Tajiri recounted that several captains informed Tamura that the lack of formal orders detailing the scope and parameters of their upcoming mission was unacceptable for them and their crews. They convinced Tamura to help them draft a memorandum outlining four principles that stipulated the conditions under which the MSA was prepared to accept while operating in Korean waters. The conditions were as follows:

- Disposal of mines laid by US and Japanese forces to be considered as an extension of navigable route clearance operations in accordance with General Order No. 1 and SCAPIN Order No. 2.

- Minesweeping will be conducted in harbors within waters south of the 38th parallel where there is no fighting.

- Operations will be executed with due regard for the safety of minesweeping vessels.

- The government will fully guarantee the rank, salary, compensation, etc. of crew members.50

These four points sought to ensure the safety and well-being of MSA crews. By declaring that MSA vessels would neither operate in combat zones nor north of the 38th parallel, nor would they clear mines not originally laid during World War II, the authors of this document sought to hold Tamura to his word, and by extension, the USN as well. Of course, these conditions had no legal force. Moreover, there is no evidence that the document was forwarded to either the USN or Ōkubo, or that either party was aware of its exact content.

Emotions still ran high after the meeting adjourned. For many participants, the political reasoning for the mission remained obtuse. Nose recalls that one captain expressed what many of his colleagues were thinking. “Why must we enter the Korean War and clear mines? Isn’t it a US operation against a third country? It is not the duty of the Japanese minesweeping force to go and clear mines in the Korean War.”51 As second in command, however, Nose was determined to follow Tamura’s lead. Seeking to set an example for his colleagues, Nose openly declared his support for the mission and pledged to face the same dangers as the men under his command. Nose’s remarks ignored the concerns of his fellow officers: why was the MSA obligated to clear mines as part of a US-led war effort? Apparently, Tamura could offer no satisfactory explanation. Instead, as Nose recorded, Tamura merely restated his vow that, “We will not cross the 38th [parallel].”52

As news spread of the MSA’s impending mission to Korean waters, frustration spread among regular sailors at Karato. Like their officers, these men expressed deep doubts about the constitutionality of their mission. As one anonymous MSA sailor put it:

Since Japan abandoned war due to its newly established constitution, at this time there is no reason to expose our lives in dangerous places for the sake of another country’s war. Moreover, we are no longer servicemen, [we are] state public servants and administrative officials… [With] the mission to rebuild Japan, [we] have willingly striven to carry out domestic minesweeping missions for reconstructing Japan. [We] cannot assent to going to war for clearing mines in another country.53

Although many personnel were former IJN sailors, they were firm believers in postwar Japan’s new identity as a pacifist nation and sought to uphold their new constitution. For these men, going to war again was not only inconceivable, but a violation of their nation’s postwar identity and constitution.54 Having survived one terrible war, the realization that they were about to possibly head back into a warzone must have felt like an impossible nightmare with no way out.

Unlike the IJN, the MSA was not a military organization and MSA personnel were not subject to any military code that might compel their obedience. Losing one’s job was the worst punishment that could legally be meted out to MSA personnel. Yet in most cases, this punishment was enough to convince many to stay despite their fury at deploying overseas. Quitting meant sending their families potentially into destitution. Moreover, minesweeping paid comparatively well because of the job’s inherent danger.55 In the end just one engineer and one staff attaché quit after citing concerns with regards to their household situation.56

Despite the MSA’s attempts at secrecy, Nose notes that a number of wives tracked down their husbands to Karato on the eve of their departure and learned that they were heading to Korean waters. One determined wife implored her husband to stay behind. “Dear! Get off the boat! I beg you not to go to Korea, please quit the minesweeping force and return home!” Yet another sailor’s wife, holding her infant child, made an even more impassioned plea: “If you insist on going, I will throw this child into the sea and die too!” To no avail. Nose says little about the emotions running through the minds of MSA sailors as they listened to these earnest pleas, but it is easy to imagine the emotional conflict and distress that many must have felt. Under a pall of mistrust and conflicted emotions, the men of the MSA prepared to once more head off to war.

“We Were Tricked”

Unofficially dubbed the “Japanese Special Minesweeping Force (Nihon tokubetsu sōkaitai),” the minesweepers at Karato were divided into four squadrons. On October 7, each squadron received orders outlining its area of operations. In accordance with Tamura’s pledge, First and Fourth Squadrons received orders to deploy below the 38th parallel to the ports of Incheon and Gunsan on October 7 and 17 respectively, while the Third Squadron was placed in reserve at Karato.57 However, the seven vessels of Second Squadron (commanded by Captain Nose), as well Tamura’s flagship Yūchidori, received a different set of orders: Nose’s squadron and the Yūchidori were to rendezvous with American warships on their way from the Japanese port of Sasebo in northern Kyūshū on October 8 and await further orders.58 Posted on the Yūchidori, Tajiri found the omission of an area of operations for Second Squadron and the Yūchidori to be especially ominous. Tajiri glumly concluded that “…if [the destination] is Wonsan, then the conditions of yesterday’s agreement (four points agreed between Tamura and captains) will not be met.”59

On October 8 at 4pm, Second Squadron arrived at its assigned rendezvous point in the Sea of Japan. Shortly thereafter, a USN 7th Fleet tug arrived and conveyed the long-awaited orders to the Yūchidori. The laconic orders got straight to the point: “Destination: Wonsan.” They further instructed the Japanese vessels to immediately cease all wireless communications of any kind, thereby putting them out of contact with each other and the Japanese mainland, as well as to enforce a total ban on sound and the emission of any light during nighttime for safety.60 As a civilian force, the MSA had no blackout curtains. Sailors rushed to cut up their blankets to cover all windows and light sources. The sailors of Second Squadron now understood without a shadow of doubt that they were heading north of the 38th parallel, contrary to Tamura’s promises.61

The following day, Second Squadron’s vessels received one final communication, a telegram from Yoshida Shigeru. Addressed to the sailors of the Special Minesweeping Force, Yoshida provided the first justification of the MSA’s mission from an elected official as well as addressed concerns that had Tamura had left unanswered. It began: “For the sake of our country’s peace and independence, the Japanese government will cooperate with the United Nations forces’ minesweeping operations in Korean waters.”62 This operation was not about Japanese security, but about the politics of Japan’s occupation and the importance of being seen as a partner in the new postwar US-UN international order. The telegram continued:

Special Minesweeping Force personnel, you will be considered to be temporarily employed by the US military from the time you leave port [in Japan] until the time you return to port. However, for the purpose of service records, you shall be treated as if you had continued to work as a government employee.63

Yoshida had addressed some of the concerns raised by captains during the meeting with Tamura on October 6. However, the announcement that Japanese vessels and their crews would be transferred to USN command implied that they were “mercenaries” of a sort; their services merely transferred back and forth as if they were commodities to be traded.

The final section of the telegram dispelled whatever lingering questions sailors had about the possibility of being exposed to danger. Addressing prior concerns about pay, Yoshida stated that sailors heading beyond the 36th parallel would receive a 150% pay rate and would receive further bonuses for each voyage, and for each voyage in which they came under enemy attack. This was the closest that any Japanese government official had come to admitting that MSA sailors should expect to face a combat situation. Reflecting on this remarkable set of orders, Tajiri noted with some distress that “…nothing was mentioned about any measures to be taken in case of emergency (such as someone being killed or wounded by enemy fire).”64 Coming to grips with Yoshida’s words, Tajiri reflected: “At last, tomorrow, Wonsan! It is a battlefield!” Perhaps to his surprise, Tajiri noted that “he was not nervous” about the possibility of facing battle despite his deep misgivings about the mission.65 Yet Tajiri found himself pondering whether he and his comrades would face the same dangers they experienced fighting the Americans. “Would there be air attacks? Perhaps we will come under naval gun fire or surprise attack?”66 As Second Squadron neared Wonsan on the night of October 9, numerous other sailors may have been wracked with similar anxieties as they realized that they were heading off to war.

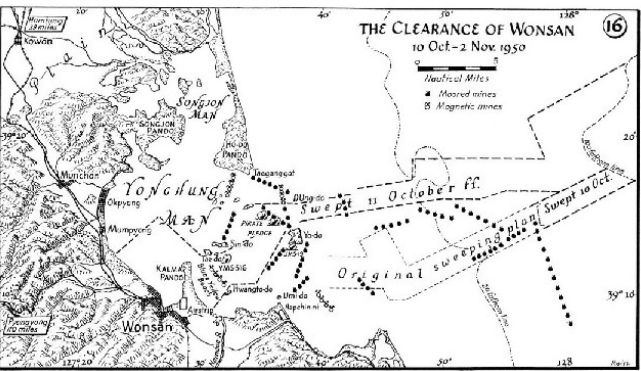

Figure 4: Map showing Wonsan Bay and locations of Soviet minefields and the channel that MSA subsequently cleared. Shōgo Nose, “Chōsen sensō ni shutsudō shita nihon no tokubetsu sōkaitai,” (March 1978): 1.

On October 10, Second Squadron arrived at Wonsan Bay. After reaching station, Nose and Tamura met with their USN counterparts and received a briefing on the scope and purpose of the upcoming operation.67 Following on the success of the landings at Incheon in September 1950, UN forces sought to land US Marines and South Korean soldiers at the North Korean port of Wonsan. The goal of this operation was the interdiction of retreating North Korean forces and the creation of a logistical staging ground for further incursions into North Korean territory. Ironically, the operation was redundant from the moment it began. Already on October 10 South Korean ground forces had entered Wonsan and captured its vital airfield, thereby eliminating the reason for the Wonsan landings. Whether due to injured pride or sheer stubbornness, the USN insisted that the landings occur anyway. In order to facilitate the landings, the USN’s minesweepers along with their Japanese and South Korean counterparts, would manage the clearing of mines, a task that USN planners anticipated would be accomplished quickly.

However, things did not go as planned. On October 12, the discovery of what ultimately amounted to 3,000 mines68 necessitated the postponement of the landings until October 26.69 Complicating matters further was the fact that the North Korean military had situated naval shore batteries to defend the bay. Until these emplacements could be destroyed, all minesweeping would occur potentially within range of enemy guns. Under these conditions, minesweepers had to clear sufficiently sizable sea-lanes to allow transports room to safely land on Wonsan’s shoreline. Joining the Japanese squadron was an American detachment of four minesweepers and a destroyer, as well as a South Korean frigate, YMS 516.70 Far from clearing mines in a noncombat zone, as the MSA officers had been ordered to do, they and their squadron found that they were serving on the frontlines of the war.

From the start, minesweeping at Wonsan proved to be deadly. On the morning of October 12, the minesweeper, USS Pirate, approached the entrance of Wonsan Bay at the head of a column of US vessels in preparation to commence minesweeping. About 3,000 meters behind the USS Pirate was the Yūchidori, which had slowed down considerably after spotting several floating mines. Observing the events from aboard the Yūchidori, Tajiri recorded what happened next.

The time was 11:15am when the lead ship (USS Pirate) entered the bay. Together with a loud reverberating ‘boom’ the lead ship was covered in water. They were hit! A mine! Everyone present on the bridge [of the Yūchidori] watched in silence…[T]he water column disappeared after 10-15 seconds. With its bow down, I could see the boat sinking rapidly. In turn the boat’s hull submerged below the sea, and it probably was another 3 minutes before the mast disappeared from sight…71

The mine blast instantly killed six of the Pirate’s crew. The 60 surviving crew members came under fire from North Korean batteries hidden on islands in the bay. The minesweeper, USS Pledge, set out to rescue the Pirate’s surviving sailors, but also came under intense fire. While taking evasive maneuvers to dodge incoming shellfire, the Pledge collided with another mine and sank.72 Five more sailors were killed in this incident. By now, the large guns of USN warships furiously returned fire at the North Korean batteries.73 Coming to the aid of the now stricken survivors of the Pirate and Pledge was the USS Redhead, which suffered extensive damage before successfully extracting the stricken USN sailors from the sea. Soon afterwards, the USN issued an order for a general withdrawal. In total, 12 Americans were killed and 92 wounded.74 The first day of mine clearing was a debacle. The significant loss of life and ensuing fighting was demoralizing for the MSA sailors. Writing about the day’s subsequent fighting, Tajiri spoke for many of his fellow sailors when he expressed a deep sense of foreboding and anxiety: “I hope that the fears I had before leaving port do not become reality…Will the continuation of minesweeping needlessly make casualties of the minesweeping force ?”75

The goal of clearing Wonsan Bay of mines in time for the commencement of amphibious landings on October 15, now looked like wishful thinking.76 North Korean resistance was unexpectedly tenacious as USN warships and North Korean batteries exchanged fire through the night of the 12th and into the following morning. It was only on October 13 that the USN finally silenced the remaining North Korean guns. With half of the American minesweeping force either sunk or critically damaged already on the first day, much of the minesweeping duties fell to the MSA. The MSA vessels waited all of October 13 for orders, but none ever came. Finally, on October 14 the USN ordered the resumption of minesweeping activities. That morning, MSA minesweepers reentered Wonsan Bay and began clearing safe channels for the USN’s landing ships. With the North Korean Shore batteries destroyed, there was no longer danger of enemy shore-based fire. Yet there remained fears that there could still be undetected North Korean forces. With memories of the disastrous events of October 12 still fresh, the Japanese crews remained on edge.77

Just five days after the sinking of the Pirate and Pledge, disaster struck again in Wonsan’s troubled waters. October 17 had begun promisingly. After four days without incident, MSA sailors were beginning to feel somewhat at ease. “Who [on this day],” as Tajiri later wrote, “would have thought that it would be a fateful day?”78 At 2:30 PM, the USN ordered the eight MSA vessels to begin sweeping for mines in Wonsan Bay. At approximately 3:30 PM, Japanese minesweeper, MS 14 collided with a mine. Again, Tajiri recorded what happened:

Along with a loud reverberating ‘boom!’ that pushed upwards from beneath our feet, the minesweeper in front of us was engulfed in a column of water and smoke. This time it was one of our minesweepers. With that column of water and smoke? Certainly, there were quite a few casualties? This was serious!79

In little less than a minute, all that remained of MS 14 was its mast, poking out from beneath the water’s surface.80 The explosion took a heavy toll on MS 14’s crew. While preparing lunch for his crewmates, Nakatani Sakatarō, the boat’s cook, died instantly when MS 14 struck the mine. Along with Nakatani, two more sailors were seriously wounded, and 13 others received lighter wounds.81 Just five years after Japan’s surrender in World War II, Japanese sailors were once again dead and wounded as a result of hostile action in a war.

Figure 5: Nakatani Sakatarō in the uniform of an MSA sailor. “Sengo senshi shita nihonjin ga ita! Ani ga hajimete kataru ’71 nenme no shinsō’” Kanaroko.

After Japanese and American vessels rescued MS 14’s beleaguered survivors from the sea, the MSA squadron received orders to temporarily cease minesweeping. On the evening of October 17, Tamura called a gathering of the squadron’s officers on his flagship to discuss the sinking of MS 14.82 The meeting must have been especially uncomfortable for Tamura. Not only had he been wrong about not crossing the 38th parallel, but his force had suffered Japan’s first military casualties of the postwar era. Outraged by the sinking of MS 14, the gathered captains told Tamura that they should return to Japan immediately. “[We] do not want to get caught up any further in this war. Stop the minesweeping. [We] should return to Japan,” complained one captain.83 Reminding Tamura of the previously agreed upon conditions for taking part in the mission, another captain stated, “The four conditions for our participation and cooperation from before our departure have all fallen apart… [We] were tricked.”84 The assembled captains decided to draft and sign a statement addressing the USN commander of the Wonsan operation that expressed their fury over the MS 14’s sinking. According to Tajiri, the statement roughly read as follows:

We refuse to continue with minesweeping. Conditions are too different from what was promised before we departed Shimonoseki. If the US military or even the commander-in-chief insists on sweeping mines, we will only do so after we conduct a sweep with small boats. There will be no further negotiations beyond this. Immediately after our arrival at Wonsan, three US and Japanese minesweepers had sunk after hitting mines. Even though [MS 14] was on a combat mission under the command of US forces, its position was different. We will not accept further casualties.85

However willing their American counterparts may have been to accept injury and death as reasonable risks, this was not part of the job description for civilian employees of the MSA.86 The civilian employees of the MSA sought to accept a situation that placed their lives at risk for a mission that was never part of their original duties. Indicative of this sentiment was Captain Nose, the second-in-command of MSA forces under Tamura, who now viewed the entire operation as one that was illegitimate for the MSA and an intolerable risk to his men’s lives. Therefore, Nose decided to join his subordinate officers in their refusal to carry out further minesweeping. Reflecting on his decision after the war, Nose wrote:

Minesweeping personnel are civil servants [in Japan] and are not obligated to risk their lives to carry out their duties, so they cannot be ordered to do so… Since no suitable minesweeping method can be found for the time being, and since it is likely that further casualties will occur if the minesweeping continues, I decided that the only alternative was to suspend the minesweeping at Wonsan. Deciding to share the same fate as the captains of the boats under my command and take full responsibility for the situation, I requested Commander-in-Chief Tamura to allow me to lead three of his minesweepers back to Japan. Commander-in-Chief Tamura accepted the request, saying that he had no choice but to do so…87

Nose’s decision was a blow to Tamura’s prestige and authority as commander of MSA forces at Wonsan. By throwing his support behind his fellow captains, Nose deprived Tamura of his support in encouraging the other captains to stay the course. In all but name, Nose and his fellow captains had carried out a mutiny against their commander and signed a letter threatening to disobey orders from the American commander of the combined fleet at Wonsan. While nobody used the term mutiny at the time, Tamura clearly could no longer command the respect of his subordinates and compel them to remain at Wonsan.

Tamura nevertheless continued to attempt to salvage the MSA’s mission. Resisting pressure to scupper the mission altogether, he tried to negotiate a deal to allow some of his crews to go home and exchange them with fresh replacements before resuming minesweeping operations.88 The American commander of minesweeping operations agreed to this request, however, the commander of the American landing force, Rear Admiral Allen Smith, was livid. Smith threatened Tamura that either Japanese vessels resume minesweeping the following morning, or he would fire on them if they did not depart for Japan within 15 minutes of the start of operations.89 With memories of the war fresh on both sides, the threatening language of Smith’s ultimatum only enraged Tamura’s captains, who learned the news from a visibly shaken and angry Tamura.90 Learning of Smith’s threat to open fire on Japanese vessels, Nose simply said: “If you are going to shoot, shoot.”91 Smith’s words only reinforced Nose and his fellow captains’ conviction that their resolve to return to Japan was the correct course.92

Tamura had tried everything to prevent the disintegration of his command, but his efforts proved futile. To his credit, he relented in the end and acknowledged the fact that his men deserved to go home if they no longer wished to remain at Wonsan.93 This seems to have restored his standing somewhat in the eyes of his subordinates. At 2PM on October 18, Tamura ordered his flagship to hoist signal flags officially approving the departure of Nose’s vessel (MS 03) as well as two other minesweepers (MS 06, and MS 17). Smith’s threats proved to be hollow, and the Japanese vessels departed Wonsan Bay without incident. On October 20, the three ships arrived at the port of Shimonoseki. In their place, the MSA dispatched the reserve squadron held back at Karato to take over their duties at Wonsan.94

With the departure of these three vessels, the MSA’s Second Squadron was left with only one minesweeper (Tamura’s flagship) and three patrol craft ill-suited for minesweeping duties (PS 02, PS 04, PS 08). Second Squadron was for all intents and purposes rendered ineffective.95

Upon returning to Japan, Nose traveled to Tokyo to report on his decision to return to Japan. The MSA leadership and the USN were furious. On October 23, the MSA stripped Nose, three other captains (one captain served under Nose on MS 03) of their duties and expelled them from the MSA’s minesweeping force.96 By contrast, the crews of the three vessels escaped suffering any repercussions. While there was no explanation for this decision, it is likely that it was due to the MSA’s need for experienced crews and fears of sparking further insubordination among other sailors.97 News of the MSA’s mission at Wonsan and subsequent “mutiny” did not leak to the Japanese media. Neither, it seems, did the firing of Nose and the three other captains appear in any news story. Despite losing his job and leading the only known instance of successful insubordination within the postwar Japanese military, Nose’s naval career did not end in 1950. Following Japan’s independence in 1952, Nose was rehired by the MSA’s successor, the MSDF, and served in multiple senior positions before retiring.98

After Nose’s departure, Tamura, and his flagship, Yūchidori, as well as the three patrol craft recommenced MSA minesweeping operations after receiving reinforcements of five minesweepers and three patrol craft from Third Squadron on October 20.99 On October 26, Wonsan’s waters were finally sufficiently cleared to permit the landing of US and South Korean forces. But the efforts of the MSA proved to be unnecessary. South Korean army units had already reached Wonsan by land, making the entire Wonsan landing redundant. Nevertheless, Wonsan remained a dangerous battlefield.

In confirmation of the worst fears of those MSA sailors who departed Wonsan, on October 19, a mine sank the South Korean frigate, YMS 516, leaving four dead and 13 missing.100 Nearly a month later, on November 15, a transport manned by Japanese sailors collided with another mine, killing all but one of its 26 crew.101 Following the Wonsan operation, MSA vessels continued to carry out minesweeping duties around the Korean peninsula until December 1950.102 Unlike at Wonsan, these operations were not conducted in combat zones and did not result in any loss of life. However, off the southern South Korean port of Mokpo, yet another MSA minesweeper was lost after hitting a shoal. Unlike MS 14, this incident did not result in any casualties.103 Compared to the Second World War, the MSA’s deployment was relatively bloodless: one dead and 15 wounded. Yet the risk of death and injury was as real as the losses suffered by USN and South Korean sailors due to North Korean mines and shellfire.

Assessing the MSA’s Deployment in Postwar Japanese History

What are we to make of the MSA’s role in the Korean War? The MSA’s participation in the Korean War occupies an awkward place in postwar Japanese political and military history. Narratives of postwar Japan typically make a firm distinction between Japan before and after 1945. But the MSA’s activities, as well as the mobilization of thousands of Japanese merchant mariners for the Korean War reveal a picture of a Japan that participated in an internationally sanctioned conflict, this time, however, not at war with the United States, but as its vassal.

Prime Minister Yoshida believed that deployment of the MSA in the US service would help repair Japan’s reputation as a responsible stakeholder in the postwar international order and hasten the end of the occupation. This led Yoshida and Ōkubo to rationalize the violation of Article 9 of the Constitution and accept the subterfuge and the deaths of Nakatani Sakatarō and numerous Japanese merchant mariners, as well as the wounding of Nakatani’s comrades aboard MS 14. Key figures in the Japanese state believed that their sacrifices of life and limb were contributing to the rebuilding of Japan’s prestige.

Since the Korean War, Japan has served multiple times as an ally in US wars. During the Vietnam War, for instance, Japan, and especially Okinawa, then directly ruled by a US military governor, provided key bases for the strategic bombing of North Vietnam. Moreover, over the decades Japan has provided military bases, recreation and recuperation facilities, and other logistical and technological support that has helped bolster US military power projection in the Asia-Pacific region. During the Korean War, of course, Japan provided these services in support of the US/UN’s war effort. However, the deployment and actions of the MSA were fundamentally unique during the Cold War era. Whereas these previous examples represented indirect, albeit considerable support of US wars and foreign policy, the deployment of the MSA along with the extensive mobilization of merchant mariners signified the first instance in which Japan directly participated in an overseas conflict in the postwar era.

Just as the MSA’s deployment represented a significant development in Japanese foreign policy, so too did it represent a major milestone in postwar Japan’s military history. Although the MSA was a civilian organization, its deployment in Korean waters transformed it by providing covert support of US/UN military operations, particularly in the case of Wonsan, located in a live combat zone during the Korean War. Additionally, the MSA served as the nucleus for Japan’s later reconstituted navy, a point that retired U.S. Admiral Arleigh Burke acknowledged in an interview aired on Japanese television on July 14, 1978.104 Consequently, the MSA’s deployment ought to be viewed as a precursor to the string of high-profile peacekeeping, minesweeping, and antipiracy missions performed by Japan’s Self Defense Forces in Iraq, Cambodia, the Indian Ocean, and South Sudan among others since the 1990s.

Japan’s SDF has assiduously avoided placing its personnel in dangerous situations and regularly imposes stringent rules of engagement for its personnel in multiple UN peacekeeping missions. Due to these measures, the SDF has never suffered any casualties in any of its overseas deployments. But the Japanese state and many observers of Japan incorrectly claim that no postwar Japanese citizen has officially deployed to an active battlefield in or died as a result of war or other enemy action. But Nakatani’s death and those of other Japanese personnel during the Korean War disprove this claim. Postwar Japan’s active military history began not with the end of the Cold War, but a mere five years after the end of the Second World War.

Notes

The story of the MSA’s minesweeping operations in the Korean War remains largely absent from English language histories of early postwar Japan. However, several Western scholars have written about the topic as part of works that examine the formation of the MSDF and Japan’s little known, albeit extensive, role in the Korean War. One such prominent author is Tessa Morris-Suzuki who has done more than any other Western scholar to reveal the depth of Japan’s overt and covert participation in the Korean War. In her chapter, “A Fire on the Other Shore?: Japan and the Korean War Order” in The Korean War in Asia: A Hidden History (2018), Morris-Suzuki briefly discusses the MSA’s actions at Wonsan and provides a unique eyewitness account in the form of the experiences of Ariyama Mikio, the captain of minesweeper MS 06. The MSA’s position within the broader framework of Japanese postwar military history has been examined by Garren Mulloy’s Defenders of Japan: The Post-Imperial Armed Forces 1946-2016, A History (2021). In particular, Mulloy work provides a brief and insightful discussion of the MSA’s postwar formation and activities in the Korean War. Mulloy’s discussion illuminate the activities and losses suffered by Japan’s merchant marine during the Korean War, in addition to introducing the little-known efforts by Japan’s merchant marine to assist the US war effort in Vietnam and their losses as a result of North Vietnamese action.

“General Order No. 1 Office of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers.” Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Accessed August 21, 2022.

“SCAPIN-2: DIRECTIVE NO. 2, OFFICE OF THE SUPREME COMMANDER FOR THE ALLIED POWERS,” Nihonkenkyū no tame no rekishijōhō, accessed June 10, 2022.

In December 1945 the Navy Ministry was renamed the Second Ministry of Demobilization, the Army Ministry became the First Ministry of Demobilization.

Yōji Kasawa, “Dai yon shō chōsen sensō to nihonjin sen’in: gunyōsen nado no jōsōin toshite,” Kaiin, no 10. (October 2007): 91.

Thomas B. Buell, Naval Leadership in Korea: The First Six Months (Washington: Naval Historical Center Department of the Navy, 2002), 33.

There seems to be some disagreement in the sources over whether Burke invited Ōkubo to his headquarters or if Burke visited Ōkubo at his office. I have used Ōkubo’s version of events for this article because of the preponderance of secondary sources supporting his recollections, but according to American naval historian Thomas B. Buell, Burke insisted he visited Ōkubo. For Burke’s account of this meeting see: Buell. Naval Leadership in Korea, 33-34.

Takeo Ōkubo, Uminari no hibi: kakusareta sengoshi no danzō (Tokyo: Kaiyō mondai kenkyūkai, 1978), 208.

“Shōwa nijyūsannen hōritsu dai nijyūhachi gō kaijōhoanchōhō,” E-Gov hōrei kensaku, accessed June 5, 2022.

For a detailed record of Burke’s conversation with Yoshida, see: Buell, Naval Leadership in Korea, 35.

Wada Haruki, The Korean War: An International History (New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2018), 138.

Hisao Ōnuma, “Chōsen sensō ni okeru nihonjin no sansen mondai.” Sensō sekinin kenkyū 31, (Spring 2001): 2-4.

Shōji Tajiri, “1950nen genzan tokubetsu sōkai no kaiko,” Sōkaibutai no rekishi.” (February 2002): 5.

Yōichi Hirama, “Sōkaitei haken: Chosen sensō ji no kyōkun,” Chūōkōron 106, no. 6 (June 1991): 128.

Ibid. The reason for the unusual silence was not due to a lack of concerns or questions. Apparently, many of the captains wished to avoid showing disrespect to Tamura, who was a graduate of a more senior class from the IJN’s naval academy on Etajima.

Hidetaka Suzuki, “Chōsen kaiiki ni shutsugeki shita nihon tokubetsu sōkaitai: sono hikari to kage,” Senshi kenkyū nenpō (March 2005), 5. This quote was reproduced by the author of this article written on behalf of the Ministry of Defense. The original quote first appeared on page 98 of a 2001 book titled, “Umi no yūjō,” by Agawa Naoyuki.

Tajiri, “1950nen genzan tokubetsu sōkai no kaiko,” 13; Hirama, “Sōkaitei haken,” 129. Second Squadron consisted of four minesweepers, three patrol craft, as well as Tamura flagship, which is listed as an airplane tender. All vessels were built for the IJN during the Second World War.

Hirama, “Sōkaitei haken,” 129. It is a testament to the prodigious number of mines and the difficulties encountered in removing them that by the time UN forces landed, South Korean units had already advanced over land and secured the beachhead. Thus, the Wonsan landings proved to be redundant. However, a few months later the mine-swept waters off Wonsan would prove invaluable in permitting the evacuation of UN forces fleeing advancing Chinese forces.

Shizuo Yamazaki, Shijitsu de kataru Chosen sensō kyōryoku no zenyō (Tokyo: Hon no izumisha, 1998), 254-255.

To this day, there remains disagreement over whether Rear Admiral Smith threatened to fire upon MSA vessels. While Tamura and fellow Japanese officers claimed that Smith threatened to fire on them, other eyewitnesses claim that Smith merely told Tamura that he was “fired.” Tamura was the only MSA officer who directly heard Smith’s comments. Consequently, there is no other firsthand source in Japanese to provide corroboration evidence. Generally, all accounts by Japanese participants at Wonsan have agreed with Tamura’s understanding of Smith’s words. I have followed this interpretation, since this is what was understood to have been said at the time among Japanese personnel.

Stephen Dwight Blanton, “A Study of the United States Navy’s Minesweeping Efforts in the Korean War” (MA Thesis, Texas Tech University), 133.

Anzō Ishimaru, “Chōsen sensō to nihon no kakawari: wasuresarareta kaijōyusō,” Senshikenkyūnenpō 11, (March 2008): 35.