Abstract: In 1969, a group of Japanese veterans returned to New Guinea to find the remains of their comrades and conduct funeral rites, one of many such postwar missions to former battlefields. The group documented its search in photographs and published a book of these photographs in 1970. This article shows how the visual cues of the photographs functioned to blur the temporal distance from war and encouraged an emotional response in the viewers by contrasting the recognizable, shattered remains of the dead with the peaceful and ostensibly timeless environment in which they were now found. The photographs also reveal unequal power relations between Japanese veteran visitors and their New Guinean hosts, and the enduring nature of the veterans’ colonial viewpoints. This article argues that the aim of the veterans in presenting these photographs to the greater public was to contribute an emotionally engaging argument against forgetting the sacrifice of veterans in the war, underlining the powerful mechanisms that allowed conservative alliances of veterans, bereaved families and politicians to bypass debates about war guilt by appealing instead to emotions connected to grief and mourning.

Keywords: war remains; Japan; veterans; World War II; New Guinea; commemoration; photographs; ikotsu shūshū (“bone-collecting”); fallen soldiers.

Introduction

In October 1969, a group composed of the members of the Japanese veteran association Tōbu Nyūginia Senyūkai (the East New Guinea Veterans Association), government officials and journalists traveled to Eastern New Guinea to locate the remains of Japanese war dead. The participants documented their four-week mission in photographs, and shortly after their return, in 1970, published a book that presented selected photographs of the mission to the greater public. The book is large format, the size of a coffee-table book or a photograph album. This article focuses on these photographs because, unlike the large bulk of other writing on missions of recovery, in this case veterans narrated their journey and experiences though a visual medium. They deployed the affective power of photography not just to document their own efforts, but to engage their domestic audience in the importance of their mission.

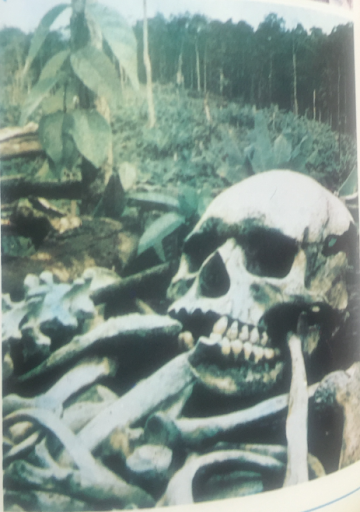

Figure 1: Tōbu Nyūginia senyūkai 1970, 74.

This article analyses the contents of this collection as an attempt to translate the war experience for an audience at home in immediate and emotionally engaging ways. The book was published just a few months after the mission itself. The first few pages consist of an overview of various battlefields in Eastern New Guinea over the three years of the fighting, authored by former Colonel Tanaka Kanegorō (Tōbu Nyūginia senyūkai, 1970). The larger proportion of the book is taken up by the photographs themselves, captioned only by a short sentence if at all, over some 130 pages containing one to three photographs each. They depict the search party, the New Guinean villagers who helped them, and amongst landscapes, animals and plants, also the bones of the dead. The photographs demonstrated the importance of the collection of remains as tangible evidence of the past, and yet, they also symbolically detached the reader from the war and its experience by marking both temporal and geographical distance through a range of devices. Caroline Brothers argues that:

Photographs are yet evidence precisely of the interplay of historically deeply rooted power relations which generate such images and make use of them. The conditions of their production and the context in which they are used determine the meanings they transmit (1997, 17, emphasis in original).

The recovery mission, and the photographs themselves, were the product of postwar tensions over the meaning of the war, the nature of the wartime soldiers’ sacrifice, and the legacy of this sacrifice for a pacifist postwar Japan.

Throughout the book, the war remains themselves acted as the hinge on which the past and the present were connected. War remains are so-called “sticky objects”: in Rumi Sakamoto’s analysis of portraits of young tokkōtai (“Kamikaze”) pilots at the Yūshūkan, the war museum attached to the Yasukuni Shrine, she argued that some objects (in that case, the portraits of young men killed in suicide missions) acquire “stickiness,” by which she means the ability to arouse emotional reactions in those who see them (2015). Building on the work of Sara Ahmed and William Conolly, Sakamoto examines the “affective economy” of such objects, drawing attention to the power they gain by being embedded in both cultural contexts and political hierarchies. Sakamoto suggests that scholars of postwar Japanese history have undervalued the power of affect in postwar memory debates in Japan (2015, 163).

|

| Figure 2: Two photos presented on the same page. The caption to the one above reads: “Mementos of the past.” The one to the photo below reads: “while crying …” (Tōbu Nyūginia senyūkai 1970, 93). |

This conceptual framework is particularly useful to the study of discourses and debates about the repatriation of remains. War remains are “sticky objects” par excellence: they prompt from their viewers a somatic response embedded in complex layers of meaning, shaped by cultural and historical frameworks. Somatic responses can be complex and contradictory: shattered, dirty, hollow-eyed skulls, or the stains of rotting flesh on tattered remnants of fabric can provoke sadness and grief, but also a physical reaction, perhaps an averting of the gaze, a shudder of revulsion, or a sharp intake of breath. The affective reach of remains passes through viewers and beyond: the tears of a mother clutching the box containing the remains of her son can engender a somatic response in those who see her crying. The affective power of war remains is similarly transmitted through the photographs that depict them. As Susie Linfield writes, “photographs excel, more than any other form of either art or journalism, in offering an immediate, viscerally emotional connection to the world” (2010, 22). Emotionally engaging photographs of emotionally disturbing remains thus functioned even more powerfully to engage viewers. They demanded an acknowledgment of the sacrifice of wartime soldiers in ways that bypassed broader arguments about war guilt, and in ways that might disrupt a younger generation’s perceived indifference to the wartime generation’s suffering.

Soldiers’ remains in postwar Japan

The 1969 mission to repatriate the remains of the dead from New Guinea was one of many missions that took place in the aftermath of the war. Some veterans’ efforts have caught domestic and international attention: Nishimura Kōkichi, who looked for the remains of comrades in New Guinea throughout the period between 1979 and his death in 2015, was the subject of a biography by Charles Happell, The Bone Man of Kokoda (Happell 2009; MacNeill 2008). From the Japanese defeat in 1945 until 2020, the Japanese government, community groups and individuals have worked to find the remains of Japanese soldiers fallen in the battlefields of the Pacific, Southeast Asia and the former prison camps of Siberia. The recovery of remains has constituted an effort on a grand scale and across vast geographical spaces: the Japanese government estimates that of the total 3.1 million war dead between 1937 and 1945, 2.1 million military men and 300,000 civilians died outside of Japan proper (Kōseishō 1997, 118). Japanese efforts to locate and repatriate the remains of fallen soldiers overseas have waxed and waned over the years. They have been resurgent since the 50th anniversary of defeat in 1995, in lockstep with acrimonious debates about historical revisionism, remilitarization, international tensions about war guilt and apologies, and the growth of the right-wing group Nippon Kaigi (Tawara 2017).

The repatriation of war remains continues to have relevance in contemporary politics: in 2016, following a scandal regarding the misidentification as Japanese of repatriated remains from the Philippines and Russia, the Japanese government reiterated its duty to repatriate fallen soldiers, enshrining this time in law its responsibility to complete this process by 2026 (Government of Japan 2016). The heated debates about the nationality of repatriated remains, and about the duty of the Japanese government to find and bring home fallen soldiers of the Asia-Pacific war, draws attention to their cultural and political significance. As Thomas Hawley has shown in the case of American soldiers lost in Vietnam, the organic matter of remains becomes imbued with meaning much larger than that held by the long-dead individual. Soldiers’ remains channel not only personal and communal grief, but they also make meaning of past wars in complex, symbolic power plays, validating some experiences over others, and legitimizing some emotions over others (2005).

In Japan, the collection of remains shaped, and was shaped by, domestic debates about how the war should be remembered, and by whom, especially in the first thirty years after the war. The landscape of war memory in Japan is often presented in easy dichotomies of victor/vanquished, perpetrator/victim, conservative/progressive, pacifist/nationalist. Veterans, fallen soldiers, and thus war remains, sit uneasily across these dichotomies, as does the appropriate way to commemorate Japan’s war dead, especially since so many of them died in unmarked graves overseas. Writing about an Australian cemetery in Japan, Joan Beaumont has stated that national war graves “speak to an implied contract between the state and its military forces: namely, that the nation will never forget anyone who dies in its defence” (2017, 171). This idea underpins the commemoration of soldiers of all nation states in the 20th century. It is entirely normalized in many societies, especially the nations that emerged victorious from the conflict, but this is not the case for Japan. In Japan, the process of celebrating the sacrifice of the tangible (human lives) for the imaginary (the nation) was disrupted, because dead bodies and grieving families were the result of a sacrifice in the service of an imagined nation now rejected, at least symbolically, by the reimagined postwar nation. In other words, in Japan, the “implied contract” between the state and the military forces has been questioned since the defeat: postwar political reforms, including the abolition of the Imperial military institutions, led to the discreditation of Japan’s war effort in a range of subtle and unsubtle ways.

It is precisely the tension over the meaning of this implied contract that is at issue in veterans’ efforts to repatriate remains, and in the photographic documentation of the 1969 search. Neither the defeat nor the disappearance of the wartime military institutions removed the need for Japanese veterans, families and communities to find, mourn and commemorate their dead. The 1969 mission to New Guinea was one of many such missions throughout the region. The “searchers,” those who devoted time and effort to locate remains in and near former battlefields, undertook their missions and documented them within these broader political and discursive contexts.

Veterans, New Guinea, and forgotten battlefields

As the veterans made clear, the search for remains in New Guinea was complex for two reasons. The first is that the nature of the war and the environment in New Guinea made finding remains difficult, especially twenty-five years after the Japanese defeat. Deaths in New Guinea were only partly due to fighting. Illness and starvation killed just as many soldiers as battles did. Veteran narratives of the war in New Guinea emphasize this point constantly: the initial delight at the arrival in a tropical paradise, especially after the harsh conditions of Manchuria where many had been stationed, is quickly replaced with anxiety about the number of men disabled by malaria and other tropical illnesses, about growing food shortages, and over time about the increasing atomization of troops as these combined elements destroyed military organization (Nukuda 1987, 57; Onda 1977, 122–123). Attempting to find remains two and a half decades later was a process rendered more complex by these conditions. Increasingly isolated and dwindling battalions had been on the move constantly, and soldiers often died alone while others moved on. Their remains were scattered across a large area and in an environment that hastened decomposition. In 1969, searchers had some success uncovering remains at the site of the former field hospital at Salamaua, or in some of the former battlefields in Finschhafen and Sattelberg. In other places along the Kokoda track or along the Markham River, they found nothing. The landscape itself had transformed since the war, and the marshy terrain and jungle environment not only disintegrated bodies, but it had over time completely hidden traces of battle and was making access difficult (Kōseishō 1997, 228).

The second reason for the complexity of the search for remains is one that the veterans themselves felt keenly and that had more to do with postwar Japan than wartime New Guinea. In the veterans’ view, New Guinea had been a crucial battlefield of the war, and three years of fighting had caused 127,600 deaths. And yet, it seemed to them that the battle of New Guinea had lost all meaning for the people of Japan in 1969. The editors of the photograph collection argued in their foreword that not only had the Japanese forgotten the war in general and the battle of New Guinea in particular, but they also failed to pay attention to the dwindling number of surviving veterans: in 1969, according to the Association, there remained only 7,000 survivors of the New Guinea campaign. The foreword to the book suggested that the damage of the fighting had reverberated through those who had survived the battle “like a terrible epidemic” (Tōbu Nyūginia senyūkai 1970, ii). In other words, it was not just the battle itself that had killed soldiers, but its legacies during life in postwar Japan. In that sense, the editors of this book rehearsed for the battle of New Guinea the theme of the “forgotten war” and “forgotten sacrifice,” a theme common throughout the postwar period in veteran memoirs and particularly in those who engaged in the search for remains. Palau veteran Funasaka Hiroshi utilized the same tropes of forgetting and abandonment to describe his compulsion to find remains on N’gaur and Peleliu, as did former volunteer nurse on Saipan Sugano Shizuko when she explained to her readers why commemorative expeditions to the Marianas were necessary (Funasaka 1977; Sugano 1965).

The veterans’ introduction to the 1970 book on the New Guinea search faithfully reflects these themes, describing veterans, most now in their mid-50s, as “almost at the beginning of old age, carrying backpacks in the heat, looking for their friends, your son, husband, father…” (Tōbu Nyūginia senyūkai 1970, ii). The introduction thus highlights the double sacrifice of the veterans for Japan, the first as soldiers in their youth in an awful battlefield, and the second made again on behalf of families in Japan, despite the veterans’ advancing age and the physical toll of the search in tropical heat. This second sacrifice was also made on behalf of the dead themselves: as the introduction states, “going back to visit our dead comrades, whose graves are covered in moss in the middle of the jungle, is the duty of the survivors, and the fulfilment of the oath we took.” The duty of survivors to the dead is a common theme of the accounts of those who searched for remains (Happell 2009; Trefalt 2015), and it speaks to their attempt to fulfill the terms of the “implied contract” between Japan and its war dead mentioned earlier.

|

| Figure 3: The short caption to this photograph tells us that the fifty-five members of the mission visited Yasukuni Shrine on 3 October 1969, before their departure (Tōbu Nyūginia senyūkai 1970, 15). |

The searchers themselves were veterans, the last remaining members of a few battalions of the 18th Army, accompanied by four journalists from prefectural newspapers in Gunma, Ibaraki and Tochigi prefectures. The searchers represented both former soldiers and officers, and varied military roles in infantry, engineer corps, field hospitals and leadership (Tōbu Nyūginia senyūkai, 1970, back page). The mission members were referred to and listed entirely as men, although the photographs in the book also include occasional depictions of Japanese women. We are not told who they are: they appear as part of the audience in commemorative services (Tōbu Nyūginia senyūkai, 1970, 55). With some exceptions, such as Sugano’s experience on Saipan mentioned earlier, the search for remains is a predominantly masculine endeavor, as is the experience of the battlefield in general, even if the broader domain of mourning and grief in Japan is more often presented as domestic and feminized. As for the remains themselves, it is likely that the great bulk of the bones unearthed during this mission were ritually cremated, and only a small portion of the remains themselves, most likely as ash, was symbolically repatriated. The war memorial at Chidorigafuchi in Tokyo has been the (albeit contested) destination of such remains (Trefalt, 2002).

The return of these veterans to New Guinea in 1969 as part of a mission facilitated by the Ministry of Welfare’s Bureau of Repatriate Welfare highlights the ongoing connections between veterans and the postwar government, and particularly the membership of the Bureau of Repatriate Welfare. This Bureau was a direct descendant of the early postwar Demobilization Ministries Numbers 1 and 2, which were the remnants of the former Imperial Ministries of the Army and the Navy, dismantled during the Occupation of Japan in 1945. When, in 1947, the Demobilization Ministries were themselves abolished, all outstanding issues of repatriation and veteran support, including eventually the search for remains, became the responsibility of a special office for Repatriate Affairs, which was in time placed under the aegis of the Ministry of Welfare (Kōseishō 1997, 144–146). There were thus many bureaucratic, administrative and personnel continuities between the wartime Imperial forces and the postwar Bureau of Repatriate Welfare.

The personal and personnel connections between wartime and postwar military and government bodies can be illustrated by the life-course of Horie Masao (1915-2022), a famous veteran of the New Guinea campaign. Horie was perhaps best known in Japan for being a paragon of active and healthy old age until his death in 2022, but he had also campaigned for the repatriation of war remains for many years. Although Horie was not part of the 1969 mission, he was a central figure in the fight for the repatriation of remains. After fighting as a lieutenant in New Guinea, a member of the 239 battalion of the 18th Army, Horie became a member of the postwar military forces, first in the ranks of the National Police Reserve, and then in the Self-Defense Forces (SDF). Upon retiring from the SDF with the rank of Lieutenant General (and as Superintendent General for the Western Army, one of five ground armies of the Self-Defense Forces), Horie was elected to Parliament in 1977 to represent the Liberal Democratic Party. He continued to work as a central spokesperson for the movement to repatriate remains even after leaving parliament in 1989 (NHK 2009; Viewpoint 2020).

The movement for the repatriation of war remains had important backers in Japanese postwar governmental and military institutions: when the New Guinea Association was fund-raising for the 1969 mission, it was able to list, among its advisers, Minister of Finance Fukuda Takeo (later Prime Minister, 1976–78), Foreign Minister Aichi Kiichi, Minister of Defense Arita Kiichi, members of the Upper House, members of the Lower House, representatives of national associations of prefectures and municipalities, as well as important private backers from major railways, banks, the Yasukuni Shrine, and famous figures from the entertainment industry such as wartime and postwar songstress Watanabe Hamako (Tōbu Nyūginia senyūkai 1969). Despite the international reach of the searches for remains, there is no evidence that the New Guinea Association asked for funding outside of Japan. The list of participants in the 1969 mission include a Japanese employee of the Australian Airline Qantas, the airline most likely to service New Guinea at the time, but the terms of his participation are unclear. The colonial administration of New Guinea, the Australian government, certainly acquiesced to the Japanese veterans’ visit, especially since preparations for New Guinea’s planned 1975 independence included consideration of the potential of Japanese investments in various local industries (Doran 2006).

The personal circumstances of individual participants differed, and the kind of unbroken connections to the postwar military and government represented by a veteran such as Horie were not replicated across the board. One of the participants in the 1969 mission was Nukuda Ichisuke, who had fought in New Guinea after several years of military service in China and Manchuria, and who was already in his mid-thirties during the war. After his demobilization, he worked as a high-school physical education teacher in Nagano Prefecture. Nukuda was able to join the mission in 1969, as he noted in his memoir, thanks to the support of the Veterans’ association, and he was grateful to be chosen to participate. When Nukuda took part in the mission, he was already battling ill-health. He was able to write his war memoir before dying of cancer in 1973 at the age of 66. These memoirs, published posthumously by his son in 1987, include a short reflection on his participation in the 1969 mission (Nukuda 1987). Though Nukuda was one of the older participants in the mission at the age of 62, he was still working, and his younger counterparts were also all employed. They were able to get special leave because the New Guinea Veterans’ Association, with its powerful backers, wrote their employers directly to request their support, affirming their employee’s crucial role in performing a national duty (Tōbu Nyūginia senyūkai 1969).

During the preparations for the 1969 mission, members of the New Guinea Veterans’ Association contemplated the potential power of the photographs of the remains of the dead, and considered how to present them to the public. In a file dated April 1969, a handwritten document elaborated on how such photographs would be presented to the public. The book of photographs was planned, with a production estimated at some fifteen to twenty copies, and there are notes about how to enlist, for public relations, the cooperation of newspapers, of prefectural chapters of the Bereaved Families’ Associations, and of each of the political parties. The notes also detail plans to hold public exhibitions of these photographs in department stores, community halls and cultural centers (Tōbu Nyūginia senyūkai 1969). The members of the Association thus understood the potential impact of the photographs and clearly planned for their dissemination to the broader public, because they were engaged in a project of memory recovery that was predicated on the emotional impact of the photographs of the dead. It is not clear whether it was the role of the accompanying journalists to take the photographs or whether the veterans themselves had access to cameras. Since the mission split up to search different areas, it is likely that there were several photographers. Nor do we have more information on the process of curating the photographs for publication within the Association’s editorial committee. It remains also unclear whether and in what circumstances the photographs were exhibited as the Association had planned before the trip.

The photographs: measuring the distance between then and now

In the photographs, the war remains themselves provide the symbolic link between the war and the postwar, and the layout of the photographs highlights the attempt by veterans to translate the experience of the war itself and of the search in New Guinea. Three striking contrasts in the book speak to the search mission’s concerns and impressions. The first is the veterans’ perception of the distance between the war and their own present in 1969, symbolized by the juxtaposition of monochrome wartime images with the colorful representation of the same landscape as photographed by the veterans. The wartime photographs are pictures taken by Allied armies: aerial shots of impenetrable mountain ranges, or landscape depictions of swampy river mouths. The veterans took color photographs, twenty-five years later, of similarly impenetrable forests, of fast flowing rivers, and muddy flats, sometimes replicating closely the vista presented by the earlier wartime photographer. The depiction of New Guinea as a hostile natural environment during wartime serves to remind readers of the conditions in which soldiers served at the time, illustrating the common theme in New Guinea veteran memoirs that their enemy was the environment as much as Allied soldiers.

Presenting this vista in color to readers in 1970 was a means, enabled by recent technological advances, to provide immediacy for those seeing the photographs. They could imagine the color of New Guinea at the time of the war, as immediate perhaps as the environment they could see with their own eyes in the present, rather than as a distant past indexed by old technology that rendered images monochrome. The presentation of historical photographs in black and white symbolically creates a world different to that available through human eyes. When the veterans showed the same landscape in monochrome and color, their choice of layout functioned both to acknowledge the distance of the wartime past, but also to redefine that distance as, perhaps, not as great as readers might have imagined. After all, the veterans themselves, and the comrades whose bodies they were searching for, had lived through that past and seen it with their own eyes, in its beautiful but also gory and terrifying colors. There could be no possibility of forgetting for the veterans, and the photographs enjoined the readers to resist forgetting, to prevent that past from sliding into the black and white that cannot be imagined as real.

In addition, the contrast between wartime photographs and colorful contemporary photographs was a way to highlight a recurring theme in Japanese memoirs of the war in the Pacific: that this hellish war had taken place in a heavenly environment, a lost paradise. In the book, the remains themselves function as the device that ties the monochrome to the colorful, and so the past to the present. The 1969 photographs of skulls, bone fragments and pieces of military equipment excavated during the mission are largely monochrome, not because of the choice of photographic film, but because all color had been leached from the remains through decades of burial. The photographs show a combination of dull white and dark dirt, as in the contrast below between the monochrome of the skulls and the striking green of the leaf on which they rest.

Figure 7: The short caption to this photograph reads:

“Young lives, protecting the nation…..” (Tōbu Nyūginia senyūkai 1970, 94).

A similar contrast was made in Illustration 1, with dull bones presented against the background of a brilliantly green forest. In that sense, the remains themselves bridged the gap between the monochrome photographs of historical landscapes and the colorful photographs taken by the searchers, or between the past and the present and heaven and hell.

But while the bones are presented in the book as the tangible black and white objects that link the colorful present to the past, they were only rarely discovered in the way depicted to the viewers of the book. Most of the searches were fruitless or yielded a much less powerful reminder of the unacknowledged death of Japanese soldiers than symbolized by universally recognizable and shocking remains such as skulls. Writing just a couple of years after his participation in the mission, Nukuda narrates his dogged and increasingly desperate search for the remains of comrades he helped bury in 1945, in a place that he knew intimately during the war, but that he had trouble recognizing in the present. The name by which the village was known by Japanese soldiers during the war did not match that used by New Guineans in the present. It took several visits, long and exhausting treks on rough tracks in vehicles that got bogged down, and eventually the kind help of the local village headman to find it. To locate the precise spot, Nukuda even had to retrace on foot a path, now overgrown, that he had walked regularly during the war (1987, 172).

Once the approximate grave site was found, the dig started over an area of four-square meters, using the paid labor of local young men. But the dirt yielded nothing. Nukuda wrote: “I felt like crying; I remembered the day of their burial, twenty-four years earlier, and I could not help thinking that this must be the place (1987, 173).” Promising the laborer’s additional pay, he urged them to dig a bit deeper.

Using a magnifying glass, I crawled around in the dirt, searching, but I could not find anything. After another hour and a half of digging, a young man held up something that glinted like gold. It was part of a watch. That’s right, I remembered, we buried the men with their watches. At last, this was it. The bones had disappeared after twenty-five years, but the spirits of 366 war dead kindly guided me to their dwelling place with this small watch part. And so they too could finally go home to their ancestral land. I sat down, overcome with emotion. Repeating ‘thank you, thank you, thank you” over and over again, I knew in my heart that I had, just now, completed a duty that had been pending for twenty-five years (ibid.).

Nukuda then created a makeshift altar, decorated it with the Japanese flag and Bougainvillea flowers, placed on its offerings of fruit and tobacco, and invited the young laborer’s to offer incense as well. For the first time in a long time, he felt that his own soul was at peace (Ibid.).

Although the traces of remains were often non-existent, or only faint as with a small watch part, as Nukuda’s account makes clear, the book of photographs, in contrast, centered on the successful disinterment of bones clearly recognizable as human. In that sense, they consciously engaged a set of emotions which would have more meaning, in the eyes of the viewer, than a small piece of metal. That piece of metal only had meaning for someone with Nukuda’s experience, who remembered burying one of his comrades still wearing his golden watch. By contrast, the hollow-eyed skulls create in all viewers the kind of visceral response that Linfield suggests is at the core of the power of photographs: she notes that photographs, more than words, “we approach […], first and foremost, through emotions” (2010, 22). If the aim of the book was to remind viewers in Japan of the sacrifice of soldiers, the prominence of recognizable human bones was a potent device. As the caption for the photograph below makes clear, the bones represent people so eloquently that readers are urged to imagine them having a conversation, now that they are congregated in the same space. It is, the caption suggests, enough to make one cry.

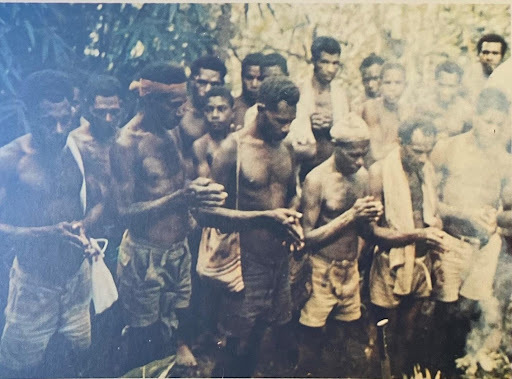

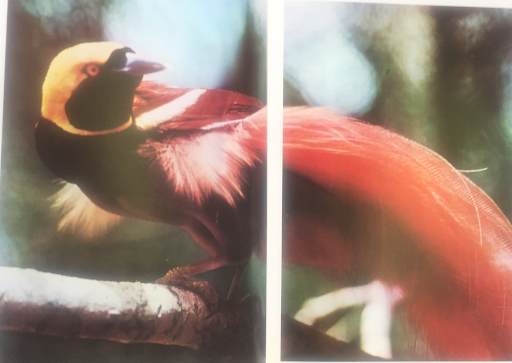

A second important contrast in the photograph book is the one made between Japan and New Guinea, a geographical superimposed on a temporal one, rehearsing again the idea of New Guinea as an innocent paradise. This contrast is made explicitly in a caption comparing a wartime photograph of a bare-breasted woman in traditional attire with the veterans’ own photographs of a young bare-chested woman holding a naked child, and a young man with an elaborate hairdo: “Local customs have not changed even now” (Tōbu Nyūginia senyūkai 1970, 44). The fascination with the “primitive” that Robert Tierney explored the narratives of prewar Japan is clearly replicated here (2010); as Lamont Lindstrom and Geoffrey White have argued, this fascination was also visible in American wartime photographs of the Pacific (Lindstrom and White, 1990). However, in the rest of the book the contrast is generally implicit, and it reflects the veterans’ gaze as tourists as well as searchers. The focus of these photographs is on the exotic landscape: flora, fauna and inhabitants are presented as colorful and beautiful, but also fundamentally different. The book opens with a two-page photograph of the colorful bird Kumul (Raggiana Bird of Paradise, now symbolized on the national flag of Papua New Guinea (PNG), and also known literally as a bird of paradise in Japanese), as shown in Illustration 9. Then, throughout there are photographs of lush forests, colorful busy markets, coconut trees and papaya trees laden with fruit, brilliant bougainvillea, and perhaps predictably, bare-breasted women and naked children (Illustration 12). These photographs provide a context for the purpose of the searchers: they are interspersed with photographs of the guides carrying the Japanese flags; a memorial covered in flowers and fruit offerings; the search party praying to the war dead.

Figure 10: The photograph goes across two pages, with a simple caption:

“Bird of Paradise” (Tōbu Nyūginia senyūkai 1970, front page).

Figure 11: A memorial to Japanese fallen soldiers overlooking the port of Madang

(Tōbu Nyūginia senyūkai 1970, 55).

Figure 12: “Women and children of Sonamu village” (Tōbu Nyūginia senyūkai 1970, 55).

For all the grief and mourning that prompted the 1969 mission, it was also in part experienced and presented as tourism, a point which reflects the tension between military deployment and its opportunities for travel. This tension has been explored extensively in research on the deployment of American troops in bases across the world, noting the cognitive dissonance between the imposition, implicitly or explicitly violent, of military occupation, and the pleasurable exploration of other cultures as a leisure activity (Gonzalez, Lipman and others 2016). Debbie Lisle draws attention to the impact of broader global transformation and accompanying discourses on soldiers’ experiences of local populations, a point she illustrates with American soldiers’ exploitation of women and children during the Cold War (2016, 127). The way in which photographs demonstrate the gaze of privileged individuals at once as soldiers, tourists and voyeurs has been explored by Carolyn O’Dwyer’s analysis (2006) of an American album of wartime photographs taken in Saipan. The visit of Japanese veterans to New Guinea in 1969, and their gaze as tourists, resonates with these analyses to some extent, not least because of the way in which New Guinean women’s bodies are presented.

However, while the photographs presented here allude to the experience of tourism to an exotic destination, they need to be understood separately from the genre of travelogue, or from research on dark tourism: their prime purpose was to make an argument to people at home about the proper acknowledgement of their dead comrades. The vicarious travel they allowed their reader to experience aimed to change the resonance of the war at home. While Nukuda, the searcher who found the small watch part, noted both his economic privilege as a Japanese visitor, and his pioneering visit in an as yet undiscovered charming location, he commented on New Guinea’s emerging potential as a peaceful and beautiful destination for travel as an aside: his central aim was depicting the pathos of these forgotten remains (1987, 175). The tensions in postwar Japanese experiences of tourism as members of a nation defeated in the Asia-Pacific War are certainly important to note: Nishino has explored these contradictory elements in a number of travelogues and memoirs (Nishino, 2017a; 2017b; 2019). Yaguchi and Yamaguchi have reflected on the awkward relationship between war memory and Japanese tourism in Hawai`i and Guam respectively (Yaguchi 2011; Yamaguchi 2006). But in the case of the photographs presented here, the identity of the searchers as veterans, and especially as veterans who feel that they have been forgotten by their own country, shapes their engagement with the landscape differently than if they were purely tourists. Beaumont argues that for Australian tourists, Kokoda has become an “extra–territorial site of commemoration’ (2016). In contrast, in 1969, when tourism was still a rare and expensive pastime, the veterans were not focusing on the creation of New Guinea as a commemorative space as much as they wanted their readers to appropriate and acknowledge the veterans’ wartime experience of New Guinea.

A notable feature in this book is the prominence of photographs of the natural environment over those of living human beings, and of the hosts of the Japanese mission. The treatment of New Guineans in the book is respectful (though we might consider photographs of bare breasted women as voyeuristic), and the help of local villagers in finding the remains of Japanese soldiers is clearly acknowledged. Nukuda’s memoir similarly acknowledges the crucial help of local men, and his ability to pay for their laboring services (1987, 172-173). However, while local people were certainly not marginal in the Japanese attempts to recover the remains, they do remain rather marginal in the photographs. There are far more photographs of landscapes, plants and birds than there are of people. This absence may be partly a reflection of the marginal position local New Guineans (or any local people) continued to have in veterans’ war memoirs as a whole. As Nishino notes, most recently in an analysis of travel writers to battle sites in the Pacific, Japanese postwar touristic encounters with former battlefields evidence more inward-looking reflection than objective assessments of the extent of the damage wrought by Japanese soldiers on these people during the war: he argues that many of these travelogues create an experience of the war as an overwhelmingly Japanese experience, though they also depict at times revelatory meetings with New Guineans and a reminder, if not a discovery, of the wartime suffering of local people (2020, 162).

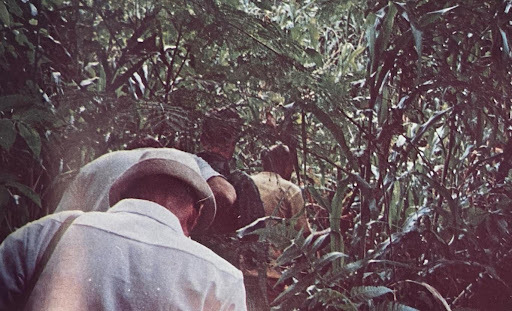

The introspection of Japanese veterans’ memoirs is not of course the exclusive domain of Japanese war memories. For example, the Australian government only relatively recently changed aspects of its sponsored museum at so-called Hellfire Pass on the Burma-Thai Railway in response to criticism that it focused too strongly on the Australian POW experiences on the railway: it now includes also references to the much greater number of Asian laborer’s who were enslaved and perished on the railway (Australian Government 2020). Nevertheless, the representation of New Guineans in the book of photographs from the 1969 mission, and in Nukuda’s memoirs as well, demonstrates their roles for the Japanese mission as guides, carriers and laborer’s, as in the illustration below.

Figure 13: The caption notes: “In the region of Boikin, this is how we

went to find the dead every day” (Tōbu Nyūginia senyūkai 1970, 92).

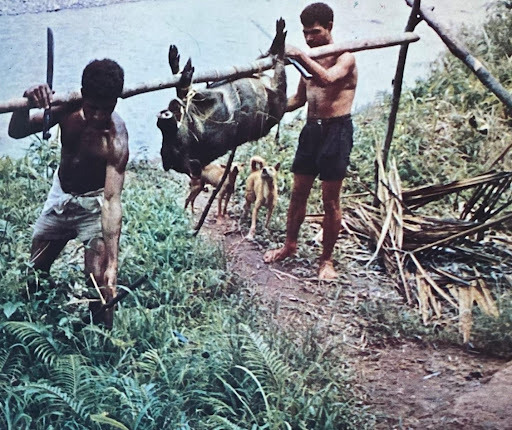

The replication of wartime roles in postwar photographs also resonates with how many other postwar memoirs rehearsed the hierarchies of race that shaped the Japanese administration of all occupied territories during the war (Trefalt 2018, 255). In these territories, ethnic Japanese stood at the apex of a descending order of ethnicities: Okinawan, Korean, Chinese, and Pacific Islanders. The depiction of New Guineans in the book of photographs rehearsed them in their “wartime” guise as porters, guides and laborer’s, and thus it provides evidence of an unchanging and uncritical assumption about racial hierarchies on the part of the photographers, at the same time as it depicts a genuine sense of appreciation for the assistance provided to the searchers. The depiction of two local men transporting between them a pig strung to a pole encompasses all these elements of the photograph book’s depiction of New Guineans: exotic, living in “traditional” or “primitive” circumstances, and used to manual labor. Such a contrast between New Guinea and Japan also positions Japan as much further advanced on the scale of modernity, an assumption that Justin Aukema explores in his article in this collection (Aukema, 2022).

Figure 14: New Guinea men carrying a pig carcass.

The caption notes only “Local customs”

(Tōbu Nyūginia senyūkai 1970, 78).

The irony in the inclusion of this image is that Japanese soldiers’ theft of pigs and other precious commodities was a central source of wartime conflict between New Guinean people and Japanese soldiers and resulted in violence in which the Japanese soldiers usually had the upper hand (Samare). It is unlikely that the veteran who took the photograph was unaware of this fact, but as neither this nor other photographs were captioned in any detail, the historical reference remained unacknowledged, at least in writing. No doubt it resonated with the memories of other Japanese New Guinea veterans, and thus belied the simplistic assumption that New Guineans had always been friendly collaborators of the Japanese. Ryōta Nishino has demonstrated how slow and discomforting the gradual recognition of this ambivalence was for Manga artist Mizuki Shigeru: as a soldier, he had frequently visited a village in New Britain, and returned to the island over several postwar journeys. His comics and essays describe Mizuki’s difficulties in reconciling the warm welcome he experienced during the war and after with his realization of the extent of the villagers’ resentment of the Japanese. He also came to understand he was welcome only because of his comparative wealth and friendship with the village head (2019). Many Australians, as Seumas Spark notes, have held similarly simplistic assumptions about the collaboration of New Guineans, largely leaving unquestioned the racism underlying sentimental references to “Fuzzy-Wuzzy Angels” (2019). Many Australians are also likely to forget or gloss over Australia’s colonial history in New Guinea (Ferns 2015).

The photographs that placed the search for remains in exotic communities and lush tropical landscapes were also a signal for their viewers that in New Guinea, life had gone on unchanged after those terrible battles; that the forest had regrown; that the bird of paradise was still flashing its colorful plumage through the trees; and that the people of New Guinea, while happy enough to help the veterans find their comrades, clearly had their own lives to lead. It was perhaps thus only the fate of the veterans, and of the families of the dead, to live a shadowy mournful postwar life while others, both Japanese and New Guinean, moved on. The focus in the book of photographs on the natural albeit exotic environment, and to a lesser extent, on its “exotic” inhabitant, served to highlight the pathos of the many lives lost in battlefields now overgrown. In the image shown below, a disinterred skeleton, in a burial place now clearly embedded in the developing root system of a nearby tree, marks the passage of time through the growth of vegetation, and suggests the gradual disappearance of the bodies.

Figure 15: This photograph is captioned:

“a body disinterred on the northern beach of Hansa bay.

It was probably an officer, the cider bottles left as they were”

(Tōbu Nyūginia senyūkai 1970, 61).

At the same time, the photograph in Illustration 15 provided proof that perhaps at least some of the dead had been buried with care and respect at the time: the position of the skeleton above suggests that he was buried at the time in a neat resting position, and with some bottles positioned near the head for the trip to the afterlife. For those who saw the photograph, and for those at home whose husband, father, son or brother was lost in New Guinea, there may have been some consolation in the idea that not all the dead had been left to rot where they lay, and that some at least had been buried with care and respect as suggested here.

Conclusion

The mission to recover war dead in New Guinea in 1969 provides an insight into the ongoing grief and mourning that shaped the postwar life of veterans and the families of the war dead. Such grief might have been assuaged, this book suggests, by finding and repatriating the bones of the dead, treating them with respect, and thus fulfilling the symbolic implied contract of their conscription, that is, that neither the state nor society would forget the sacrifice of fallen soldiers. The 1969 mission was part of a broader and complex trend of commemoration through the retrieval of remains that continues to this day, albeit with very different participants and fewer direct connections with the dead (Trefalt 2017). The photographs of the 1969 mission draw our attention to the emotional elements of the searches for remains, and ways in which veterans and the families of the dead attempted to engage what they perceived as an uncaring or ambivalent audience at home. The photographs were embedded not just in discursive economies about the virtue of sacrifice during the war, the masculinity of war and commemoration, or the relative position in economic wealth and development of postwar Japan and postwar New Guinea. They were also embedded in affective economies of mourning, grief, and loss. For many veterans and bereaved families, a pacifism that did not recognize the sacrifice of the dead was a shallow and meaningless concept. Sugano Shizuko, who experienced the war as a volunteer army nurse in Saipan, told her readers repeatedly that a true appreciation of peace, and therefore of pacifism, must be based on an appreciation of the reality of the soldiers’ sacrifice, rather than on empty euphemisms (1965, 84, 155). The veterans of the 1969 mission used the ‘sticky objects” of bones, and their mediation through photographs, to make a similar point, in a book that enjoined its readers not to forget, despite the ever-receding past in which the war had taken place. The photographs utilized the pictures of the bones for their powerful emotional leverage. Their planned exhibition in community centers and department stores across Japan represented an appeal not to allow the sacrifice of wartime soldiers fade from the memory of the Japanese population.

How the war dead, veterans and Bereaved Families shaped postwar discourses on the war, on citizenship and on national identity is a topic that deserves more attention, not least because it offers part of the explanation for the enduring appeal of postwar conservatism and the failure of progressive explanations of the war. This failure has been exemplified by the popularity of infamous cartoonist Kobayashi Yoshinori (Shields 2013) and critic Katō Norihiro (2005) who aroused controversy over historical revisionism. It is worth paying attention to how this conservatism was shaped not only by debate about political ideologies, but also by the ability of political parties in government to support specific causes and gain from their emotional power. The backing of successive postwar governments of search missions to find and repatriate remains reminds us to consider more carefully the many elements that shaped the postwar Japanese public sphere, including the grief and mourning that the veterans prompted readers to experience through the photographs discussed here.

Acknowledgments

When I first encountered the book at the center of this article, I did not think it centrally relevant to my research, but I took a few of my own photographs of it to remind myself of its contents. My dismissal of the evidence these photographs presented, and my concern with written narratives over images, made me exactly the kind of historian condemned by Caroline Brothers for failing to appreciate the power of photographs (1997). Under pandemic lockdown conditions in Melbourne for several months in 2020 and with no access to other primary sources, my careless record was the start of this article. A draft was first presented at the conference “Re-examining Asia-Pacific War Memories,” organized at the Nichibunken in Kyoto and held online in December 2020. I wish to thank the organizers of the conference for prompting research during this global crisis, and for enabling such a critical and collegial research forum. I thank Ryōta Nishino, Daniel Milne, Justin Aukema, Mahon Murphy and Lamont Lindstrom for their thoughtful comments on this article, as well as their patience during my ongoing struggle to access sources. A fortuitous, last-minute trip to the National Library of Australia in Canberra, where a fragile copy of this book is kept, and the kindness of its librarians in organizing its delivery from the stacks in record time, allowed me to finalize the manuscript. I wish to express my gratitude for the invaluable and generous help of Australian studies specialist Dr Yoko Harada in research assistance in Tokyo. I also thank the Japan-PNG Association for its careful preservation of the documents left in its care by the Tōbu Niūginia senyūkai and its valuable cooperation with researchers in difficult pandemic times. Finally, I thank the last survivor of the New Guinea Veterans’ Association, Horie Masao, who was kind enough to communicate his permission to reproduce the photographs presented here, and his son, Takahashi Masazumi, who assisted in email communications.

References

Australian Government, Department of Veterans’ Affairs. 2020. “Hellfire Pass Interpretive Centre and Memorial.” 17 November. (accessed 15 April 2021).

Beaumont, Joan. 2016. “The Diplomacy of Extra-territorial Heritage: The Kokoda Track, Papua New Guinea.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 22 (5): 355-367.

Beaumont, Joan. 2017. “The Yokohama War Cemetery, Japan: Imperial, National and Local Remembrance.” In Patrick Finney (ed.) Remembering the Second World War. New York: Routledge, 158–174.

Brothers, Caroline. 1997. War and Photography. London: Routledge.

Doran, Stuart (ed). 2006. Australia and Papua New Guinea, 1966–1969. Canberra: Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

Kōseishō Shakai-Engokyoku 50-nen shi henshū iinkai (ed). 1997. Engo gojūnen shi [50 Years of Welfare]. Tokyo: Gyōsei.

Ferns, Nicholas. 2015. “PNG marks 40 years of independence, still feeling the effects of Australian Colonialism.” The Conversation, 15 September.

Funasaka, Hiroshi. 2000. Hitsuwa Parao senki [Belau Secret War Memoir]. Tokyo: Kōjinsha. First published as Gyokusai sen no kotō ni daigi ga nakatta [No Good Reason for a Suicide Battle on a Lonely Island (1977)].

Gonzalez, Vernadette Vicuña, and Lipman, Jana K. 2016. “Tours of Duty and Tours of Leisure.” American Quarterly 68 no. 3: 507–521.

Government of Japan. 2016. “Senbotsu sha no ikotsu shūshū no suishin ni kansuru hōritsu.” [Law Regarding Progress of the Repatriation of Remains of the War Dead], 1 April (accessed 4 February 2021).

Happell, Charles. 2009. The Bone Man of Kokoda: The Extraordinary Story of Kōkichi Nishimura and the Kokoda Track. Sydney: Pan Macmillan Australia.

Hawley, Thomas M. 2005. The Remains of War: Bodies, Politics and the Search for American Soldiers Unaccounted for in Southeast Asia. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Katō Norihiro. 2005. Haisengoron [Post-Defeat]. Tokyo: Chikuma Shobō.

Lindstrom, Lamont and Geoffrey M. White. 1990. Island Encounters: Black and White Memories of the Pacific War. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Linfield, Susie. 2010. The Cruel Radiance: Photography and Political Violence. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lisle, Debbie. 2016. Holidays in the Danger Zone: Entanglements of War and Tourism. Minneapolis MN: University of Minnesota Press.

MacNeill, David. 2008. “Magnificent Obsession: Japan’s Bone Man and the World War II Dead in the Pacific.” The Asia-Pacific Journal/Japan Focus 6 (7)

Nihon Hōsō Kyōkai. 2009. “Rikugun dai jūhachi gun sanbō Horie Masao-san” [Mr. Masao Horiuchi, Staff Officer, the 18th Army] (accessed 12 March 2021).

Nishino, Ryōta. 2017a. “The Awakening of a Journalist’s Historical Consciousness: Sasa Yukie’s Pacific Island Journeys of 2005-2006.” Japanese Studies 37 (1): 71–88.

Nishino, Ryōta. 2017b. “From Memory Making to Money Making?” Pacific Historical Review 86 (3): 443–471.

Nishino, Ryōta. 2019. “Better Late than Never? Mizuki Shigeru’s Trans-War Reflections on Journeys to New Britain Island.” Japan Review 32: 107–126.

Nishino, Ryōta. 2020. “Pacific War Battle Sites through the Eyes of Japanese Travel Writers: Vicarious Consumer Travel and Emotional Performance in Travelogues.” History and Memory 32 (2): 146–175.

Nukuda, Ichisuke. 1987. Chichi no senki: Tōbu Nyūginia sen [Father’s War Memoir: Eastern New Guinea War] Tsuru: Hōwa shuppan.

O’Dwyer, Carolyn. 2004. “Tropic Knights and Hula Belles: War and Tourism in the South Pacific.” Journal for Cultural Research 1 (8): 33–50.

Onda Shigetaka (ed). 1977. Ningen no kiroku: Tōbu Nyūginia sen no kiroku [The People’s Memoirs: Record of the War in Eastern New Guinea] Tokyo: Gendaishi shuppan.

Sakamoto, Rumi. 2015. “Mobilizing Affect for Collective War Memory.” Cultural Studies, 29 (2): 158–184.

Samare, Seno. 2003. Interview with Iwamoto Hiromitsu, “Remembering the War in New Guinea.” The Australian Japan Research Project (accessed 17 March 2021).

Shields, James Mark. 2013. “Revisioning a Japanese Spiritual Recovery through Manga: Yasukuni and the Aesthetics and Ideology of Kobayashi Yoshinori’s ‘Gomanism’.” The Asia-Pacific Journal 11 (47:7).

Spark, Seumas. 2019. “White Man’s War: New Guineans Experience of War 1942–1945.” Aus-PNG Network, Lowy Institute. 27 February (accessed 8 June 2021).

Sugano Shizuko. 1965. Saipan ni inoru [Praying on Saipan]. Tokyo: Shufu no tomosha.

Tawara Yoshifumi. 2017. “What is the Aim of Nippon Kaigi, the Ultra-Right Organization that Supports Japan’s Abe Administration?” The Asia-Pacific Journal/Japan Focus 15 (21.

Tierney, Robert T. 2010. Tropics of Savagery: The Culture of Japanese Empire in Comparative Frame. Honolulu: University of Hawai`i Press.

Tōbu Nyūginia senyūkai. 1969. “Tōbu Nyūginia senbotsusha irei junpai narabi ni seifu shūkotsu jigyō kyōryokudan hai shuisho.” [Pilgrimage to commemorate the War Dead in Eastern New Guinea and a Report on Bone Collection by the Government], Archives of the Japan New Guinea Association.

Tōbu Nyūginia senyūkai. 1970. Nyūginia e no michi [Road to New Guinea] Tokyo: Tōbu Nyūginia senyūkai.

Trefalt, Beatrice. 2002. “War, Commemoration, and National Identity in Japan, 1868–1975.” In Sandra Wilson (ed.) Nation and Nationalism in Japan. London: Routledge. 115–134.

Trefalt, Beatrice. 2015. “The Endless Search for Dead Men: Funasaka Hiroshi and Fallen Soldiers in Postwar Japan.” In Ernest Koh and Christina Twomey (eds.). The Pacific War: Aftermaths, Remembrance, Culture. London: Routledge. 270–281.

Trefalt, Beatrice. 2017. “Collecting Bones: Japanese Missions for the Repatriation of War Remains and the Unfinished Business of the Asia-Pacific War.” Australian Humanities Review, no. 61.

Trefalt, Beatrice. 2018. “The Battle of Saipan in Japanese Civilian Memoirs: Non-combatants, Soldiers and the Complexities of Surrender.” The Journal of Pacific History, 53 (3): 252–267.

Viewpoint Henshūkyoku. 2020. “Horie Masao-san: senyū, nantoshite mo sokoku ni.” [Mr. Masao Horie: Comrades, we will do anything to get to our motherland] Viewpoint. 15 August (accessed 12 March 2021).

Yaguchi Yūjin. 2011. Akogare no Hawaii: Nihonjin no Hawaii kan. [Hankering for Hawai’i: How the Japanese Have Seen Hawai’i] Tokyo: Chūōkōron.

Yamaguchi Makoto. 2006. Guamu to Nihonjin: sensō wo umetateta rakuen. [Guam and the Japanese: A Paradise that Buried and Built on the War] Tokyo: Iwanami shoten.