Abstract: This essay suggests that the renewed politicization and militarization of the maritime sphere is a product of the increasing need to re-legitimise the current state-based political order. Order can be understood as particular configurations of boundaries as they define political communities through various practices of inclusion and exclusion: East Asian seas have become one of the final frontiers for sustaining national developmental projects, they mark the boundaries between the Chinese, Japanese, and South Korean nation-states, and are also borderlands in the global order as they separate ‘East’ from ‘West’ and thereby differentiate the ‘civilized’ self from the ‘barbarian’ other.

Keywords: Maritime Politics, Danger, Boundary, Order, China, Japan, South Korea

Introduction

The hallmark of East Asia is the pace and pattern with which regional economies have been growing since the 1950s. This development has been so impressive that the World Bank famously named it the East Asia Miracle. Rapid economic development is still raising questions about the future of the region today. After the emergence of Japan Inc., Korea Inc., and the Small (Asian) Tigers Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore had led to the notion of the Asia-Pacific Century in the 1980s and 1990s, respectively, China’s rise prompted predictions about an impending Asian Century in the 2000s. This geopolitical gaze has over the last decade gained hegemonic status in the debates about the future of East Asia, the Asia-Pacific, and, most recently, the Indo-Pacific.

The maritime sphere is the centre stage on which these debates unfold. But why and how in the era of the globalized economy and the Cold War over for three decades, has the maritime sphere become imbued with increasing levels of danger again? What made maritime territorial disputes heat up, and what drives anxieties over sea lane security? Why are the connecting elements of the maritime sphere and the ocean as ecological system absent from the discourse and practice of (international) politics?

To answer these questions, it is necessary to adopt a regional perspective for transcending the separation of economics from politics and to avoid essentialising geography, regime type, or stages of economic development. This is particularly significant as seemingly disparate issues get politicized and recruited into meta-narratives of regional and global (maritime) security, such as the power shift thesis and the (liberal) rules-based order narrative. This study suggests that the renewed militarization of the maritime sphere as it follows the discursive portrayal of ocean-related issues as existential national security threats, must be seen as an outflow of the increasing need to re-legitimise current state-based political orders.1

Modernity, Orders and Borders

To understand what is at stake, it is useful to think in categories that encompass social and political transformations over longer historical periods: modernity or modernities. Modernity, as it continues to define the social and political orders in the 21st century, entails several dimensions: “an idea of scientific knowledge, the necessity for a vastly extended state and its armed forces, a temporality of progress (modernization), and, as complement to hugely extended state power, the state’s legitimacy through its claim to represent a people”.2

Accordingly, the world, particularly the realm of international politics, is conceived as being dangerous; only a strong state is able to improve the “solitary, poore, nasty, brutish and short” nature of human existence.3 Therefore, inside the territorial borders all individuals have to cede their natural rights to a strong sovereign authority, the Leviathan, in order for the state to enforce the social contract among people. Outside, life remains dangerous and insecure. In essence, as David Campbell points out, this means that “when one confronts the fear of early and violent death, one becomes willing to regulate oneself and to accept external regulations that will secure life against its dangers. The fear of death pulls the self together.”4

As a consequence, “ironically, then, the overcoming of fear requires the institutionalization of fear”, in the form of external threats and the institutions that identify – that is, first define and then defend – the national community from these threats.5 The maintenance of authority necessitates the separation of inside from outside. In other words, “Borders are set up to define places that are safe and unsafe, to distinguish us from them”.6 Danger constitutes the boundaries between the ‘self’ and the ‘other’, and at the same time disciplines the ‘self’.

In modern and contemporary Northeast Asia, these dangers came in the form of repeating cycles of invasion and occupation, first in the form of European and U.S. imperialisms, followed by Japanese imperialism directed at China and Korea and, later, in the form of Soviet, Chinese, North Korean and US threats, respectively. According to these state-centred historical narratives, political and economic weakness invites disorder and destruction. Hence, ‘catching up’ with the great powers of the time, in terms of socio-economic and military development, has been imperative. Since the late 19th century, Chinese, Japanese and South Korean elites have, therefore, all been striving to build ‘rich nations and strong armies’. Even after the primary sources of danger disappeared at the end of the global Cold War, the need for socially engineered rapid economic development and technological progress persisted in the minds of the elites while being preserved in state institutions. And the much shorter period in which this “compressed development” has occurred relative to the European and North American experiences also implies that the consequences of rapid economic development have become accentuated.7 Hence, socially constructed threats in the maritime sphere have become increasingly important for political elites to uphold the levels of danger required to legitimize the continuation of their long-standing national modernization projects, including for disciplining the people to sacrifice for them. The need to pull the self together in the face of dangers from the seas, stabilizes states’ ideational and institutional underpinnings. These processes unfold through bordering practices at three levels or scales.

Securing Society

The stability of modern society and, with it, the stability of the state, is predicated on a social order based on the nuclear family, general education, full employment, and social insurance coverage.8 Economic prosperity is crucial for the maintenance of these social structures. Therefore, in their efforts to boost national economies and alleviate the vast array of mounting social – and political – problems, the Chinese, Japanese, and South Korean governments have come to place more and more emphasis on the oceans.

Often under the ‘blue economy’ heading, developmentalist discourses have been emphasizing the ‘rich’ and ‘abundant’ natural resources offered by the oceanic container and stressed the limitless business potentials waiting to be exploited through the commercialization of the vast seas and the exploitation of the immense market potentials beyond. As a consequence, marine ecosystems are commodified to create opportunities for employment and consumption. As the promotion of new visionaries such as the ‘Ocean State’, ‘Ocean G–5’ and ‘Maritime Power’ since the early 2000s indicates, these policies have been supporting long-standing national modernization projects and helped to maintain pertaining social and political structures. They serve to uphold the fiction of never-ending and universally beneficial progress. Thus, the danger of societal and political disorder spurred ocean development and thereby reinforced the boundary between the inside of the safe and peaceful (orderly) modern society on one side, and the dangerous and wild, disorderly ocean on the other. In extreme cases, these boundaries have materialised in the damming of reclaimed areas and were cast into the concrete of coastal breakwaters or sea walls. Very tangibly, massive construction projects boosted the industrial sectors linked to the very economic, bureaucratic and political interest groups who had been promoting national modernization projects for decades (Fig. 1). As such, developmental discourses frequently marginalize the questions of social and ecological sustainability that are crucial for future prosperity.

Yet, endeavours to exploit the ostensible riches of the oceans go far beyond shorelines. They have spurred efforts to expand national territory through the generous drawing and redrawing of baselines which, according to the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, mark the land-sea boundary, from where the 12 nautical mile-wide territorial sea and 200 nautical mile-wide the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) extend. Due to their retaining of vast overseas possessions, the former colonial powers of Australia, France, the United Kingdom and the United States, benefitted most. Having obtained relatively minor stakes and getting increasingly anxious about the future of their developmental trajectories, the view of the oceans as treasure troves or gold mines gained traction especially among Chinese, Japanese and Korean elites eager to rejuvenate their nations. These views gave rise to legally controversial projects of building up lone shoals, reefs and rocks into EEZ-generating islands, notably in the case of China. Moreover, official efforts to control as much marine resources as possible also created, and escalated, disputes over the delimitation of the many overlapping EEZ claims in the semi-enclosed seas of East Asia. These are, in turn, inextricably linked to disputes about territorial sovereignty over maritime features. There, material concerns about access to natural resources reinforce overwhelmingly symbolic concerns about national independence and sovereignty.

Securing the Nation

Danger does not exist “independently of those to whom it may become a threat”.9 It is mutually produced. Since the mid-1990s, levels of danger have markedly increased in the form of challenges to China’s, Japan’s, and South Korea’s sovereign control over disputed maritime territories and zones. These national boundaries between the insides and outsides of national political communities, projected onto two-dimensional cartographic maps, became both more relevant and increasingly contested. Hence, discourses of danger as they originate from and at the same time perpetuate territorial disputes, reproduce a given political order. And that order remains deeply conditioned by the traumatic events of the first half of the 20th century.

This insight concerns all maritime disputes that China, Japan and the Koreas have among themselves and with other neighbouring countries. An emblematic case is the contention over the Dokdo/Takeshima rocks in the Sea of Japan/East Sea that continues to divide two of the US’ closest democratic allies; Japan and South Korea. Bitter disagreements over Imperial Japan’s colonization of the Korean peninsula and pertaining atrocities such as forced labour in factories and systematic abduction of women to serve in wartime brothels crystallizes at these rocks. The dispute poisons the bilateral relationship to an extent that it even hampers trilateral security cooperation over North Korea and China. Importantly, the focus on these rocks blanks-out the violence that the respective elites inflicted on their own people – for both, waging war and for achieving economic development at break-neck speed throughout the post-war years.

The securitization of the maritime sphere in public discourses and subsequent militarization through actual troop presence became even more pronounced in places where bordering practices at multiple scales overlap. This is the case in the East China Sea where China and Japan (and South Korea) not only fight over the delimitation of EEZ for the rights to exploit natural gas, but where China, Japan (and Taiwan) also dispute one another’s claims to sovereignty in the Diaoyu/Senkaku islets. Despite frequent invocation as the drivers of increasing tensions, pertaining economic benefits are negligible as these sovereignty disputes are primarily rooted in nationalist historiography.

In the East China Sea, the threat from rising China to Japan materialized, since the mid-1990s, in steadily increasing Chinese oceanographic research and naval activities around the contested islets. Especially after two controversies in September 2010 and September 2012 accelerated the downward spiral in bilateral relations, the increasing frequency of Chinese flotillas transiting through the Okinawa island chain to the Western Pacific aroused concern. Even when not challenging Japanese claims and conforming to Japanese interpretations of the law of the seas’ navigational regimes, these activities were understood as signifiers for the threat of China.10

Amid the deterioration of Sino-Japanese and Sino-US relations, exemplified by the growing number of Chinese “incursions”, into Japan’s Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) – first established to protect US military installations there – rose considerably. Without a basis in international law, serving exclusively military purposes, and reaching far beyond even claimed territories, ADIZs are thus one of the clearest manifestations of how danger is mutually produced, rather than objectively given. The statistics of danger show that Japan Air Self-Defense Force fighter jet dispatches to identify and intercept Chinese aircraft that crossed the ADIZ’s security-political boundary outnumbered those against Russian aircraft for the first time in 2012.11 The Chinese declaration of its own ADIZ over the East China Sea in November 2013 raised the levels of danger yet another notch (Fig. 2).

At the same time, Chinese sources hinted at establishing another of these zones over the South China Sea. Together with the international, especially the US response, this points to the larger geopolitical calculations at play. Understanding these geopolitical bordering practices is crucial for explaining the escalation that would lead to the 2016 arbitral award against China in favour of the Philippines, and that prompted the Chinese leadership to embark on large-scale land-reclamation in the Spratly area from 2014 onwards.

Securing the Civilization

Not only the gold rush for marine resources and antagonistic constructions of national identities, but also efforts to stabilize the mental maps that order the world, have inscribed new divisions into the maritime sphere.

Perceiving a ‘power shift’ from ‘West’ to ‘East’, from the U.S. to Japan in the 1980s and early 1990s, and to China since the late 1990s, strategists in Washington have been anxious about the shrinking of their sphere of influence. Long before the reinvention of the Indo-Pacific as a strategic space to counter Chinese influence, they sought to preserve primacy in East Asian seas, including through the anchoring of associated roles for their Japanese and Australian allies. At the same time, Chinese leaders have been anxious to regain their status as a great power or regional hegemon, as imagined retrospectively, and projected back into the past.

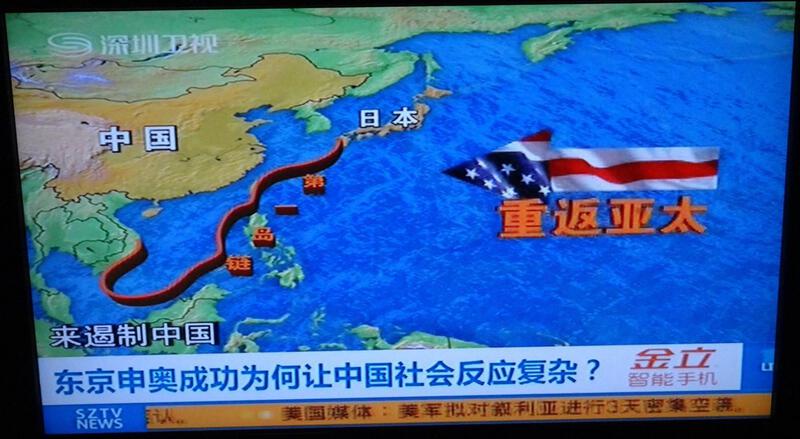

The danger produced from this antagonistic interaction reinscribed the boundary between ‘East’ and ‘West’ along the former perimeter of defence against the Communist Threat, originally drawn by former U.S. Secretary of State Dean Acheson in January 1950.12 Hence, the Korean Peninsula, the East China Sea, Taiwan – and the South China Sea – continue to be contested frontiers in the ostensible civilizational struggle. This bordering effect became visible in the way the Obama administration implemented its pivot to the Asia-Pacific, and in how it was perceived by the leadership in Beijing (Fig. 3).

This escalation would hardly have been possible without recourse, by all sides, to the narrative of sea lanes of communication (SLOC) security. In stark contrast to the reality of globalized production chains and transnationalized maritime transport, actual and aspiring great powers created geopolitical imperatives for enhancing control over spheres of influence while forging new alliance relationships. Despite great power conflict being the greatest danger to the public good of free-flowing maritime transport, Japanese officials have been seeking to secure their nationally conceived SLOC (Fig. 4) mainly against potential Chinese aggression, and Chinese officials, conversely, against the possibility that the US and Japan would block them to strangle their national economy. These policies have produced the effects that have long been researched as security dilemma or security paradox.

On the one hand, China’s economic catching up shifted and challenged the cognitive boundaries that had long differentiated the developed ‘West’ from the developing ‘East’. Established actors’ resistance to this reordering of the mental map accentuated bordering practices that aimed at reinscribing the ‘East’-‘West’ division. This, in turn, strengthened the Chinese leadership’s resolve to accelerate the ‘rejuvenation’ of the country, such as through the proclamation of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013. It also triggered the decision to embark on massive land reclamation in the Spratlys with the aim of creating a military buffer zone in the South China Sea. On the other hand, the US and especially its Australian and Japanese allies, worried about Chinese moves and, anxious about declining US power, reached out to new partners. To India in particular. Various initiatives for militarily securing ‘freedom’ and ‘openness’ across the ‘Indo-Pacific’ emerged. Following, countering, and mirroring the BRI, these came to encompass strategies for infrastructure development throughout Asia, extending to Africa.

Conclusion

The reinforced emphasis on ‘security’ and ‘stability’ that informs the discussed bordering practices does not mean that all things remain unchanged, however. Rather, they indicate that previously taken-for-granted realities have become increasingly questioned. The ensuing revelation of the contingent nature of order increases levels of uncertainty because it opens space for thinking a range of alternate courses of action. Hence, the maritime sphere has become a battle ground for the contest between progressive and conservative forces, not only in shaping new global or regional orders. Increasingly repressive practices at home also point to the precariousness of the post-war era growth paradigms and the pertaining social and political institutions, in Northeast Asia, and elsewhere.

This essay contextualizes key arguments from Danger, Development and Legitimacy in East Asian Maritime Politics: Securing the Seas, Securing the State (Routledge Asia’s Transformation series, 2018) in current debates about maritime security and order in the ‘Indo-Pacific’. It has been funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) – Projektnummer 449899997.

Selection of related articles in the Asia-Pacific Journal Japan Focus

McCormack, Gavan. Japan, Australia, and the Rejigging of Asia-Pacific Alliances.

Kingston, Jeff. The Emptiness of Japan’s Values Diplomacy in Asia.

Maedomari, Hiromori. Okinawa Demands Democracy: The Heavy Hand of Japanese and American Rule.

Wada, Hiruki. Overcoming the San Francisco System: One Japanese Person’s View.

Paik, Nak-Chung. South Korea’s Candlelight Revolution and the Future of the Korean Peninsula.

Tanter, Richard. Touring the American empire of bases with the Marines.

Hara, Kimie. Okinawa, Taiwan, and the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands in United States–Japan–China Relations.

Hara, Kimie. The San Francisco Peace Treaty and Frontier Problems in the Regional Order in East Asia: A Sixty Year Perspective.

Notes

This argument is summarized in Christian Wirth, “Securing the Seas, Securing the State: Hope, Danger and the Politics of Order in the Asia-Pacific”, Political Geography vol. 53 (2016): 76–85.

Stephan Feuchtwang, “Civilisation and Its Discontents in Contemporary China”, The Asia-Pacific Journal vol. 10, iss. 30, no. 2 (July 2012).

Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan, or, The Matter, Forme, and Power of a Common Wealth, Ecclesiasticall and Civil, printed for Andrew Crooke, edited by McPherson C.B. (Harmondsworth: Pelican Books, 1968), p. 186.

David Campbell, Writing Security: US Foreign Policy and the Politics of Identity (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1992), p. 65.

Hugh D. Whittaker, Tianbiao Zhu, Timothy Sturgeon, Mon Han Tsai, and Toshie Okita, “Compressed Development”, Studies in Comparative International Development vol. 45 (2010): 439–467.

Ministry of Defense of Japan, p. 176; “ASDF Scrambles against China Hit Record, Exceeding Russia”, Asahi Shimbun, 18 April 2013,

Kimie Hara, Cold War Frontiers in the Asia Pacific: Divided Territories in the San Francisco System (New York: Routledge, 2006).