Abstract: This paper examines how the Asia-Pacific War is presented in the new textbooks for the recently upgraded “special subject” of moral education in Japanese elementary schools. Three stories are analyzed to show the discursive strategies utilized by the authors and the moral values presented. As the analysis reveals, the image of the war created by the stories is highly selective and profoundly revisionist.

Keywords: moral education, historical revisionism, nationalism, Asia-Pacific War

Introduction

By upgrading moral education to a formal school subject in elementary schools (2018) and junior high schools (2019) the Abe administration and its allies in the Japanese establishment1 reached an important milestone in realizing their vision of Japan as a “beautiful country” (utsukushii kuni). In their view, this “beautification” will be achieved by replacing the postwar legal order with a semiauthoritarian constitution (Repeta 2013) and by overcoming what they deem a “masochistic view of history” (jigyaku shikan). They blame the latter for a lack of self-confidence among Japanese youth which leads to social pathologies such as bullying and child suicide (Abe 2007). This is the rationale behind the conservatives’ relentless pursuit of educational reform and support for a revisionist understanding of the Asia-Pacific War.

While rewriting history to accommodate new findings and research interests is a normal process, historical revisionism re-interprets history from a decidedly political logic and denies any knowledge that does not fit pre-defined aims (Richter 2008; 47; Saaler 2005, 23–25). In the Japanese case these aims are the strengthening of national pride and allegiance to the state. To attain this, revisionists construct a “‘bright’ narrative” (Saaler 2005, 24) of Japanese history, including the Asia-Pacific War. They claim that the war was a glorious struggle for Asian liberation and omit the dark sides of Japanese colonial rule as well as the war crimes committed by the Japanese military in Nanjing, Okinawa and elsewhere. Obviously, revisionist ideas overlap considerably with nationalist and conservative thought, as well as with nihonjinron – a bundle of theories revolving around the idea of Japanese uniqueness and superiority (Saaler 2005, 24). An important strategy of revisionists is to utilize a deep-rooted ‘victim consciousness’ with respect to the war – as symbolized by the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the air-raids on Tokyo and other major cities – to push aside ‘dark memories’ thereby enabling the ‘bright narrative’ of a just war (cf. Takahashi 2004). Following this logic, there is a striking absence of the ‘Asian others’ in revisionist narratives (Richter 2011, 197).

School textbooks play a central role in Japanese historical revisionism. The struggle over education and textbooks goes back to the 1950s when the conservative government promoted patriotism as a counter to the labor movement and to facilitate rearmament (Ōmori 2018, 181–195). Moral education was reinstalled in 1958 even though its predecessor before and during wartime had been widely blamed for spreading militarism and ultranationalism. State control over textbooks was also restored; by the mid-1950s, the Ministry of Education (henceforth MoE) began censoring them for treating Japan’s modern history in a way they deemed too “scientific”; this meant that they provided information about the Asia-Pacific War that was not conducive to patriotism (Nozaki and Selden 2009, 5–6). Instead, a narrative of national victimhood was encouraged in order to deflect attention from Japan’s war atrocities. This was the starting point of a decade-long discursive struggle between the conservative establishment and the mostly progressive teachers, with textbooks serving the former group as “weapons of mass instruction”2.

The slow demise of socialist opposition since the 1970s and a corresponding shift to the right in Japanese society brought about calls for a “healthy patriotism” in the 1980s (Hood 2003, 78–84). This facilitated education reforms in the 1990s and 2000s such as the obligation to display the national flag and sing the Kimigayo (national anthem) in school and university ceremonies, the creation of a moral education textbook series by the MoE called Notebook of the Heart (Kokoro no nōto) and a history textbook series based on ‘alternative facts’ about Japanese modern history (Atarashii rekishi kyōkasho). The latter was written by Tsukurukai, a private organization with close ties to LDP politicians (Saaler 2016, 4). Despite the LDP’s dominance and the MoE’s sympathy for these reforms, the attempt to gain control over the discourse in Japanese classrooms failed, as usage of the Notebook of the Heart could not be enforced. Schools used their freedom to choose other history textbooks and the New History Textbook secured only a miniscule market share.

However, the LDP managed to turn the tide in 2006 when it pushed through a revision of the Fundamental Law of Education (kyōiku kihon-hō) thereby establishing patriotism as a compulsory element of Japanese school education (McNeill and Lebowitz 2007). In Abe’s second term beginning in 2012 he continued the pursuit of education reform emphasized by the slogan “Taking back education!” This meant further strengthening state control over schools and diminishing the influence of teachers and the Japan’s Teacher Union (LDP 2012, 9–10).

This resulted in the new moral education subject which features two new control mechanisms. Firstly, an evaluation of the students’ performance that pressures them into adopting the ‘correct’ moral convictions, the so-called moral items (tokumoku) as laid out in the curriculum guidelines (gakushū shidō yōryō) (Ōmori 2018, 29–33). Secondly, a new generation of compulsory state licensed textbooks (kentei kyōkasho) was introduced. Both reforms limit the teacher’s ability to use self-prepared educational material – a strategy which in the past had enabled teachers to undermine the state’s effort to instill conservative ideas (Cai 2008, 189).

The Abe administration employed elaborate strategies to overcome resistance: The new textbooks were not directly written under the auspices of the MOE like the preceding Notebook of the Heart (and its revised edition Our Morals), but instead were published by eight private publishers. Moreover, the right to choose one of the eight textbook series that were licensed by the MOE remains with local school authorities which provides a semblance of free choice. Furthermore, the new textbooks’ contents appear to be less controversial than their predecessors. While Notebook of the Heart was criticized for neglecting liberal and democratic values (Miyake 2003, 125, 130–1), the new textbooks contain colorful images seemingly reflecting diversity and gender-equality.

However, as the following analysis reveals, the authors use subtle discursive strategies to convey nationalist and revisionist messages in several of the stories. It demonstrates that the new moral education subject is not only used to control the discourse on morals but also on history as the textbooks glorify Japanese military conduct in the Asia-Pacific War in biased and misleading ways. After the failure of the New History Textbook, a new strategy with regard to history education becomes apparent. The new moral education in elementary schools provides a strategy to subject children to revisionist messages at an early age.

To identify the discursive strategies applied in the textbooks and to understand their intended effects, I analyze the three stories about the Asia-Pacific War featuring the Tokyo Shoseki textbook series New Morals (Atarashii dōtoku) for elementary schools, which is one of two textbooks with the highest market-share.3 For this examination, I use critical discourse analysis (CDA) as laid out by Jäger & Maier (2009). Two concepts of CDA are especially useful for analyzing textbook stories: Firstly, it allows for inclusion of pictures and illustrations that play a big role in elementary school textbooks (Friedrich & Jäger 2011). Secondly, its concept of “discursive entanglements” makes it possible to identify strategies that are related to the thematic structure of the text (cf. Jäger & Maier 2009, 47). This concept is derived from an understanding of discourses as “flow[s] of knowledge through time” (Jäger & Maier 2009, 35) that can become entangled by discourse participants to create certain effects. While this analysis makes heavy use of the drawings and pictures, the right to reproduce them could not be obtained from the publisher. It has therefore been necessary to provide detailed descriptions of the material.

Story I: The Great Ginkgo Tree that Defended the Hometown4

The first story about the Asia-Pacific War in the Tokyo Shoseki textbook series is a third- person narrative in the book for the fourth grade. Its protagonist is an ancient ginkgo tree, which, together with other trees, prevents a fire disaster after a US air raid on Tokyo. The story mixes fact with fiction as Tobiki is a real tree standing on the premises of the Tobiki Inari Shrine in Oshiage (Sumida district), and was in fact damaged during an air raid. The story is put into the category “Good things about the country (kuni) and hometown (kyōdo)”, that corresponds to the guideline’s moral item patriotism (“loving attitude toward the hometown and the country”) (MoE 2017, 169).

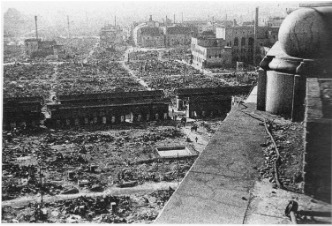

After the Bombing of Tokyo, March 10, 1945 (public domain)

Summary

The story revolves around a ginkgo tree at the Tobiki Inari shrine which “is already living for more than 500 years”. The reader learns that there is a “legend” (iitsutae) about it: Tobiki – literally meaning “flying tree” – once grew out of a stick that was left stuck in the ground after a windstorm. The locals interpreted this as a good omen and built a shrine that was later named after the “flying tree”. Below the text, a photograph shows the sturdy trunk and darkened bark of the real tree. Below the treetop is a white shide, a paper streamer that is often used in Shintō to demarcate a sacred or ritual space, spanning the tree. In the background, we see a fence and parts of a shrine building.

The next paragraph mentions that the tree’s trunk is blackened by fire yet many branches continue to grow out of it. The question is raised why it looks that way. The answer is given by a painting below showing several trees amidst raging fires. On a closer look, house roofs can be identified in the flames. The sky, consisting of a thin line of gloomy blue above the red blaze, reveals the fire’s origin: several black airplanes dropping bombs.

The text goes on to explain that Japan was in a war in “1945 (Shōwa 12)” and that many buildings in Tokyo were destroyed by the Great Tokyo Air Raid (Tokyo daikūshū) on March 10th. The reader learns that most bombs were specifically designed to cause fires which spread quickly among the wooden buildings, however, Tobiki extinguished the flames with the help of several other trees thus preventing the fire from spreading to the shrine and neighboring buildings.

Tobiki’s burnt bark is described as a consequence of this heroic deed. The next picture shows the tree’s black trunk against the morning sky; on a patch, the bark is shining in a blueish- green and five shoots are growing out of it. In front of it, three children stand in awe: a little girl who is pointing her finger toward the shoots, behind her a little boy and a taller boy wearing a black school uniform.

The text explains that Tobiki came back to life because its roots had remained undamaged. Seeing the unexpected growth, the people – who were “on the brink of losing hope” – happily exclaimed: “The big ginkgo tree is coming back!”. On the last page, a resident is quoted saying: “Let’s follow the big ginkgo tree’s example and rebuild our hometown (furusato)!”

Thus, Tobiki encouraged the inhabitants to rebuild their ward (machi). Below is another photograph of today’s Tobiki, leading back to the story’s beginning. This time it is taken from a distance showing the big trunk dwarfed by a huge tree-top. Two shrine buildings can be seen, one on each side of Tobiki. The final paragraph informs the reader that Tobiki is a “designated natural monument” of Sumida and is held in high regard by the locals as a symbol of the defense of the hometown.

Analysis

“The great ginkgo tree that defended the hometown“ is a story of the category “good things (yoi tokoro) about the land and the hometown” reflecting the curriculum’s moral item patriotism. While a story about the “good things” of today’s Japan would be an obvious choice – for example a story about people helping each other after a natural disaster – the authors instead chose a historic narrative about the war. This alone suggests that the war was a “good thing”, which is in line with the revisionist ‘bright narrative’ of a just war.

Since moral education is mainly about exemplifying moral behavior, how is patriotism portrayed in the story? It is embodied in the trees’ self-sacrifice for the greater good: Tobiki and his arboreal comrades quench the fire with their own bodies in order to protect the furusato. In defending it, they perish. It is only Tobiki, the holy tree, who comes back to life. This can be interpreted as a reference to prewar and wartime militaristic education as expressed in the Imperial Rescript on Education (1890) with its commandment “Should emergency arise, offer yourselves courageously to the State”. As the illustrations suggest, the furusato – representing Japan – entirely consists of shrine buildings and is thus a sacred place. It thereby reproduces the ultranationalist image of Japan as a land of the gods (kami no kuni) and equates Japan with the Shintō religion. The story thus creates a discursive entanglement not only between patriotism and the war but also with the Shintō religion. This is emphasized by the photograph of Tobiki decorated with the shide. For the children, this provides an allusion to the Asia-Pacific War as a “holy war” (seisen).

The following discursive strategies can be identified in the story. Firstly, the omission of Japanese soldiers, for example military police or air-raid defenses. This has been identified as a strategy in prior research on Japanese textbooks (Barnard 2003, 58–62). Even in the postwar scene that shows people mourning for the burnt trees, the Japanese are represented exclusively by children, thereby underlining their innocence.

Secondly, the authors provide no historical context, especially with regard to the question why and how Japan was in a state of permanent war in the years 1931-1945, beginning in China and Manchuria and continuing across the Asia-Pacific. This is a more general problem. As there is no history education in elementary school the children are unlikely to have any prior knowledge about the Asia-Pacific War. This makes them susceptible to revisionist messages.

Here the Asia-Pacific War is presented exclusively as a conflict in which Japan was attacked by nameless foreign enemies who bombarded a defenseless Tokyo. This historical vacuum may be contrasted with the specificity of the event’s description, as the Great Tokyo Air Raid is vividly portrayed. This is another strategy that accentuates the relevance of these selective facts. Through the entanglement of the discourses on Shintō, patriotism and war, the children further learn to associate Japan with the Shintō religion as well as to value the self-sacrifice of the Japanese people underlining a victim consciousness in the Asia-Pacific War.

Story II: The Girl with the White Flag5

The second story about the Asia-Pacific War comes from the sixth-grade textbook of the series and is a short version of the well-known autobiographical story The Girl with the White Flag (shirahata no shōjo) written by Higa Tomiko in the late 1980s and published in Japanese (1989) and English (1991). It covers the author’s traumatic childhood experience of the Battle of Okinawa, her becoming the motif of a famous war photograph, and the reunion in 1988 with the American photographer who had taken it. Curiously, the name of the original author, who is also the protagonist, is not mentioned in the text. It is only through the photograph that the reader understands that the story is based on real events. It is allocated to the category “international understanding – international friendship” (kokusai-rikai, kokusai-shinzen) – a phrasing that is identical with the corresponding moral item in the curriculum guideline (MoE 2017, 169).

The Girl with the White Flag, John Hendrickson, June 25,1945, (public domain)

Summary

The story begins with the nameless first-person narrator – her first name Tomiko is only mentioned later – describing her participation in a peace demonstration in New York in 1988. We learn that she held a placard with a black-and-white photograph on it showing a little girl clad in mompe (Japanese farmer’s pants) and waving a white flag. She reveals, that this girl is herself in 1945 at the age of seven. Below this paragraph is a drawing of a young woman wearing a colorful yukata and holding a placard with the above-mentioned photograph on it, captioned with the English words “Searching for this photographer”.

The narrator explains that she came to New York to find the military photographer who had taken the picture when she “surrendered with a white flag in her hand on Okinawa island at the end of the Pacific War”. She first saw the photograph in 1977 when she accidently “met her seven-year-old self” in a photobook. The black-and-white photograph shows a skinny girl in baggy clothes standing barefooted in front of a heap of rubble. Her left arm is caught in movement as if waving or shielding her face. Her right hand tightly grips a crooked stick with a white flag attached to its top.

In the text below, the narrator remembers the war. She explains that she dwelled in a cave together with an elderly couple – an old man who had lost both hands and legs, and a blind elderly woman. They made the flag for her, while she cried continuously. She explains that she had met them after wandering around alone, exhausted, hungry and having lost the will to live. The text continues with her inner voice: “Let’s not live any longer. Yes. If I’m going to die anyway, let’s find a nice cave and sleep in it. I haven’t eaten for three days so I can die in my asleep.”

Below, another drawing depicts the moment, when the girl receives the flag from the elderly couple – her eyes wide open with surprise and anxiety. Defying his mutilations, the old man’s posture is upright; his tanned face has a calm and friendly expression. In contrast, the woman is shown in the background, stretching out her hands towards the girl as if to hold her back.

The scene is explained in the text above. After several days in the cave, they heard an announcement of the American forces instructing all refugees to come out at once – otherwise they would be bombed. Instead of leaving together, the couple prepared a white flag for the girl, so Tomiko – named here for the first time – could leave safely. She asks them to go with her but “the two physically handicapped chose to stay”. Tomiko mentions that she didn’t speak about these events for a long time because she felt guilty about having left the elders.

As the years passed, she wished to speak about the “friendliness of the elderly couple” and in 1987 made the story public.

The narrative than takes a somewhat abrupt shift. Tomiko states that she started to think about the photographer at that time and wanted to meet him. This opportunity arose in 1988, when she travelled to the US to take part in a peace demonstration in New York.6 Thus, Tomiko’s story circles back to its beginning. She states that “through cooperation of many people” she could identify the photographer, adding “God didn’t forsake me”. The final pages of the story describe the reunion of Tomiko and the photographer John Hendrickson, whom she wanted to meet to express “heartfelt feelings of gratitude”. When they meet – Tomiko went all the way to his home in Texas – Hendrickson asks her, why she had been waving at him, when he took the picture. Tomiko explains: “My father told me that I should wave and smile happily in the last moment of my life when somebody was shooting at me”. Hendrickson apologizes for having scared her and takes out his camera with the words: “This is the camera that scared you”. When Tomiko bursts into tears, Hendrickson apologizes again with a “shaking voice and shaking hands” for making her remember the war. He then asks Tomiko if he could take another picture and instructs her to wave as she did back in 1945. When Hendrickson takes it, Tomiko says that she feels “as if a weight of 43 years fell from my shoulders.” Nevertheless, she adds that “my Okinawa war has not ended” and expresses her determination to share her story to prevent such “unfortunate events” from occurring again in the future.

Analysis

As mentioned above, this story is drawn from a much longer original. While the textbook version spans only six pages, the original is a book of 205 pages. Both are told from Tomiko’s perspective as a first-person narrative. The textbook authors use Higa’s first-person voice to tell their modified and highly selective version of the story to convey a revisionist message.

A close reading of the textbook and the original book reveals no major discrepancies with regard to the main story. However, several subplots are omitted which significantly distorts the meaning of the narrative. These omissions are in line with the revisionist strategies identified above. For example, in the original story a Japanese soldier tries to kill Tomiko to prevent surrender (Higa 1991, 73–4). This comfortably fits the construction of a benign Japanese self-image as well as concealing the role of Japanese soldiers. The textbook authors use Higa’s story to present the Japanese military and civilian populations as heroic (smiling and waving in the face of death) and selfless (the elderly couple). This starkly contrasts with the original, in which Higa writes that she witnessed the killing of an innocent mother by a Japanese soldier, leading her to conclude that “War makes people crazy” (Higa 1991, 94).

The textbook narrative is especially problematic as it glosses over the fact that many Okinawan civilians were murdered or forced to commit mass suicide (shūdan jiketsu) by Japanese soldiers during the battle (Aniya 2008). The story likewise ignores the fact that Okinawan war memory differs in fundamentals from that of many Japanese and should be treated separately (Takahashi 2004, 6–7).

It is surprising that this story was chosen for elementary grade moral education. Firstly, the tragedy of the story stirs up emotions which are likely to provoke questions that are not answered in the text. The children are left alone with deeply unsettling impressions about the Battle of Okinawa and the fate of children and citizens. Secondly, the story seems too difficult because of the lack of context, its dual plot and multiple leaps in time. For example, it is not explicitly mentioned in the beginning that the photographer is an American. While adults can use their contextual knowledge to infer this information, the children are likely to be puzzled when Tomiko states that she went to the US to find the photographer. Moreover, the children do not necessarily know the meaning of war photography. In their Lebenswelt, taking pictures is a leisure activity generally associated with happy or commemorative occasions. In this light, Hendrickson might appear as a selfish person and his act of taking the suffering girl’s photograph deeply inappropriate. That Tomiko wants to visit him to thank him might appear incomprehensible from this perspective.

Finally, the textbook’s version of Higa’s story is not an obvious example for international friendship as there is no prospect for a meaningful relationship between the two in the future; the reunion between Tomiko and Hendrickson is primarily valuable for remedying Tomiko’s trauma, which had been caused by the foreign side in the first place. Elementary school students, unfamiliar with the concept of catharsis, will not understand her feelings of relief when Hendrickson takes a picture of her for the second time.

Why, however, was this story chosen by the textbook authors and accepted by the MOE regulators despite these issues and ambiguities? I argue that it was chosen because the story serves a dual purpose, which is mirrored in its dual structure: while the episode of Tomiko’s reunion with Hendrickson is used for the purpose of teaching “international understanding – international friendship” – the second, hidden function of the story is to teach a revisionist view of the wartime episode. As in story one, in the absence of any discussion of the origins and reasons for the war or the Japan-Okinawa-US relationship at the time, Japan, and specifically Okinawa, are presented as innocent victims of foreign aggression. Furthermore, the discursive entanglement of “international understanding” and the war in the story enables the authors to connect Japanese/Okinawan victim consciousness to the area of international relations.

To achieve this, the Japanese side is represented by Tomiko, an innocent child, while the US side, represented by Hendrickson, is portrayed in a positive if perhaps ambivalent light. On the one hand, the harmony of their meeting and Tomiko’s relief at finding the photographer emphasize that the hostility between the two nations has been replaced by friendship. The peace demo in New York further reinforces the image of the peaceful Americans in harmony with Japanese striving for international peace. On the other hand, however, the story presents a view of the US as a cruel enemy in the past who invaded Okinawa for no specific reason.

Moreover, the fact alone that the peace demonstration takes place in New York (not in Okinawa or Tokyo) might suggest that US aggression still needs to be held in check by vigilant activists. Secondly, Tomiko’s act of surrender suggests that even civilians were not necessarily safe from the American soldiers. Only an unmistakable signal – the white-flag – permitted a safe capitulation. This leads us to a major omission with regard to the original book. As a photograph in it reveals, Tomiko was not alone in her moment of “surrender” but was in fact walking with a group of capitulating Japanese soldiers (Higa 1991, 109).7

Again, not only soldiers, but all Japanese adult men are absent in the story (with the exception of the old man who is obviously not “fit for action”). Instead, readers are shown innocent civilians who pose no threat: a couple that is not only elderly but also handicapped, and a little girl. This emphasizes Japanese victimhood and implies that the relationship with the US is – or should be – based on Japanese forgiveness and American remorse as symbolized by Hendrickson’s apology he makes with “shaking voice and shaking hands”.

The dual structure of the story is reflected in the moral values presented in it. As mentioned above, the central value of the episode of the reunion of Tomiko and the American photographer is international friendship. The wartime episode, on the other hand, might be an example of self-sacrifice on the part of the elderly couple who forfeit their lives to let the young Tomiko survive. In contrast to story one, whose protagonist and helpers are humanized trees, in story two the elderly couple are presented as human role models.

Courage and heroism are also important moral values in the story, as the reader recalls Tomiko waving and smiling in the face of death, perhaps inspired by her father’s words conveying the message that emotions – such as fear – have to be suppressed. Perhaps the story provoked these questions in the children’s minds: if an enemy soldier was about to kill me, would I have the courage to smile and wave instead of running away? Would I be able to smile instead of crying?

Story III: In the Midst of the Great Tokyo Air Raid8

The third war story revisits the Great Tokyo Air Raid of 1945 and can also be found in the sixth-grade textbook. This time the topic is categorized as “irreplaceable life” (kakegae no nai seimei) reflecting the curriculum’s moral item: “preciousness of life” (seimei no tōtosa). Like both previous war stories, it is based on historical events. It was first published in the 1971 book The Great Tokyo Air Raid. Records of March 10th Shōwa 20 by the writer and activist Saotome Katsumoto (1971, 76–89) and is based on an interview with Musha Miyo, the protagonist of the story. It is one of the longest stories in the textbook series, six pages. The first part is told by an anonymous third-person narrator; the second part comprises two first- person narratives by Musha and head nurse (fuchō) Yamada.

Nakamise shopping street in Asakusa, March 10, 1945, Saotome Katsumoto, ed,

The Collection of Tokyo Air Raids Photographs.

Tokyo: Bensei Shuppan, 2015, 278 (public domain)

Summary

The first page shows a colored drawing of a woman with her newborn in a hospital bed. A nurse is standing next to her, carefully tucking in her blanket. The room is dark; only a light- cone shines on the bed from above. The story’s first paragraph provides the background for this scene: three years after the onset of the “Pacific War” in 1945, Tokyo was bombarded for several days by American B29 bombers and was transformed into “a devastated landscape as far as the eye could see”. The air raids before dawn on March 10th alone “burned 26,000 buildings and more than 80,000 people died.” Musha’s story is narrated in the same factual style. She checks into the Aioi hospital at 3:00 p.m. on March 9th to give birth. After nightfall, the air raid siren sounds and “hostile planes” approach. When all windows are covered and the lights switched off, Musha is about to deliver her child. As there is a “breathtaking uncertainty whether the delivery or the air raid would occur first”, hospital director Eguchi and head nurse Yamada calm her. Finally, Musha’s child is born shortly before the hospital is engulfed by a “rain of bombs”. Musha and the newborn are transferred to a stretcher before eight patients and fourteen nurses form a group to evacuate together. A patient, walking next to the stretcher, helps secure the baby. In the final segment of the first double page, Musha and head nurse Yamada narrate the group’s escape.

The second double page shows a large colored drawing depicting the group as it makes its way through the burning ruins. The stretcher with Musha and her newborn is shown in their midst along with two patients. Their brown clothes contrast with the nurses’ white gowns. Next to the stretcher a man with a white helmet is identified as doctor Eguchi. Everybody is wearing a head protection except Musha, whose vulnerability is thus accentuated. Flames are visible in the background and on the left. Two of the nurses leading the group have a terrified look on their faces, while another nurse in the center of the group displays a determined expression.

Musha tells the reader that she still remembers her worries about her child. Her primary concern, however, seemed to be the weight of the stretcher and therefore her being a burden to the group (“The futon alone had a considerable weight. I was worrying about that constantly”). She says: “Doctor, it would have been alright if you had left me in the hospital.” Dr. Eguchi in turn alludes to his own death: “Can a doctor live on if he kills his patient?” Yet Musha insists and urges the group to abandon her and flee. It is only when Eguchi pulls the blanket over her head that she accepts the situation. Finally, she concludes her story by mentioning that the group found shelter near Ryōgoku station and states how grateful she was for being saved.

In the next segment, head nurse Yamada states that the stretcher indeed was heavy and that the group carried it for more than five hours. When they stopped at a railway underpass, a new danger arises in the form of a crowd of refugees. The nurses worry that the crowd might accidently hurt Musha and the child. They call out: “Here are patients. A newborn and her mother!”. Thus, they save their lives once more. Below are two illustrations: one a colored drawing showing white-clad nurses surrounding the stretcher and spreading their arms to shield it from the dark mass of refugees. The other on the final page is a black-and-white photograph showing Tokyo’s devastated cityscape.

Analysis

Exhibit three offers striking similarities with that of story one. Although the narratives are in different categories (story one: “good things about the country” and story three: “the irreplaceable life”), both revolve around the air raids on Tokyo, have a factual basis, and primarily extoll the value of self-sacrifice. Considering that there are only three wartime stories in the books, the repetition of tales pertaining to the Great Tokyo Air Raid puts strong emphasis on the topic.

Given the relatively older age of the pupils, usually twelve years in the sixth grade, there are two major differences from the first story. Firstly, they are presented with greater specificity: while the origin of the bombers in the first story remains unclear, it is here made explicit that the attackers are Americans – the same enemy that invaded Okinawa, as learned from the second story. Secondly, the protagonist and the main characters are humans, not trees, and can thus serve as role models.

The official moral item of this story, the “irreplaceable life”, is shown through the tireless efforts of Dr. Eguchi and the nurses to protect Musha’s and the newborn’s lives. However, self-sacrifice remains central since two out of three main characters – the protagonist Musha and Dr. Eguchi – speak about their readiness to sacrifice themselves in order to protect others.

Further moral values in the story presented as emblematic of the Japanese people are cooperation, courage and endurance (carrying the stretcher for five hours).

Again, all military personnel are excluded from representation, again reinforcing the image of Japan as a victim of foreign aggression. The story’s only male character, Dr. Eguchi, is associated with healing.

The newborn is serving three purposes in this context: its vulnerability further underscores the tragedy and horrors of war, the innocence of the Japanese and the cruelty of the enemy.

Instead of fighting and killing – as the Americans do – the Japanese are depicted as giving birth, caring for and protecting each other and willingness to sacrifice for the group.

No mention is made of the fact that the real Musha lost fifteen family members that night (Saotome 1971, 81), indeed, the story was utilized for a completely different purpose in an article in the communist newspaper Akahata: “Burnt bodies piling up like mountains became the tragic end of the people who fell victim to a militarism that had headed straight to war. Despite their old age the survivors continue to tell about their experience so that such a tragedy will never repeat” (Akahata, 2018).

Conclusion

The analysis of the three stories about the Asia-Pacific War shows that they are designed to evoke emotions and consciousness of Japanese victimhood and to obscure the Japanese role in the road to empire and war in line with the revisionist ‘bright narrative’.

This is primarily achieved by reducing the Asia-Pacific War to the last year only. It is presented as an attack against the inhabitants of Tokyo (story one and three) and – in story two – as an American invasion of Okinawa. The colonization and war in Asia are omitted. By this reduction, the stories convey a sense that Japan was an innocent victim of Western aggression.

Accordingly, the stories exclusively focus on the Japanese “self” (notably including Japanese children) and omit the perspectives of Asian “others”, especially the victims of Japanese aggression or non-Japanese imperial subjects such as Koreans, Chinese, Indonesians, Malaysians and Pacific Islanders. The Okinawan case, however, is an intermediate case.

While being a part of Japan, the Okinawan war experience was unique. Not only was it the only battle fought in Japan, it was also a conflict that was not limited to American and Japanese forces but also involved large numbers of Okinawan and Korean troops. In addition, the issues are complicated by the role of the Japanese military in relationship to the Okinawan population, notably the imposition of forced mass-suicide and in some cases the killing by Japanese soldiers of Okinawan civilians. Our discussion of the textbooks pays particular attention to the omission of these sensitive issues which distort the role of the Japanese military in Okinawa.

Following the premises of historical revisionism, “peace” is rarely mentioned in story two and is nowhere discussed explicitly as a value. While all three stories illustrate the horrors of war, war is simultaneously presented as a time of glory in which the Japanese displayed their superior moral qualities, as illustrated by the nurses in the third story. The war is presented as a matter of pride as the first story indicates (“Good things about the country and hometown”). This is also apparent in story two in its textbook form: by contrast to the original narrative in the book, which interprets the war as a catastrophe that brings out the worst in people, the textbook version uses the story to present the Japanese – represented by Tomiko and the elderly couple – as virtuous, caring and heroic (smiling and waving in the face of death).

The revisionism in the current generation of textbooks – here represented by the Tokyo Shoseki series – embodies a certain subtlety. One reason is, somewhat paradoxically, the omission of both Japanese soldiers and Asian ‘others’ in the framing of the war. With these omissions, the Japanese military is not glorified directly. Equally, the American and Asian ‘others’ are not explicitly portrayed negatively. Furthermore, the tennō and other symbols of Japanese ultranationalism such as Yasukuni shrine, are not mentioned in these textbooks.

The findings further suggest that revisionist elites in politics and bureaucracy (mis-)use the “special subject” moral education to shape children’s historical consciousness at a young age prior to and outside of history education in middle school. I suggest that this should be seen in light of the earlier failed attempt to establish the dominance of the revisionist New History Textbook in Japanese schools.

Another problematic finding is that the three war narratives present self-sacrifice as an important moral value. This stands in stark contrast to the proclaimed goal of reducing child suicides and alludes to the militarist education of prewar Japan that centered on the glorification of self-sacrifice for the tennō.

While it is impossible to determine to what degree children will be influenced by this, the promotion of revisionism in the educational system could have long-term implications for essential matters such as constitutional revision. The suppression of the ‘dark memories’ of modern history, especially the history of empire and war, might even work toward a comeback of Japanese militarism. That the Ministry of Defense recently published a “Defense White Paper” for children reveals the determination of right-wing elites to influence children even further in this direction.9

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank the editor and my colleague Stanislav Reichert, M.A. for valuable and constructive suggestions on this paper. Many thanks also go to Tanja Budde, M.A. of the academic writing center at Tübingen University.

References

Abe Shinzō, Policy Speech by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe to the 166th Session of the Diet, 2007.

Akahata Shimbun, Kyō no chōryū [Today’s current], 10 March 2018.

Aniya Masaaki 2008, “Compulsory Mass Suicide, the Battle of Okinawa, and Japan’s Textbook Controversy”, The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus.

Asahi Shimbun, Jūman no inochi, ichiyoru de… mōka no naka, akachan to nigeta haha no hanashi [100 000 souls in one night … The story of a mother who fled amidst raging flames with her baby], 8 March 2018.

Barnard, Christopher, Language, ideology and Japanese history textbooks, London: Routledge, 2003.

Friedrich, Sebastian and Jäger, Margarete, “Die Kritische Diskursanalyse und die Bilder. Methodologische und methodische Überlegungen zu einer Erweiterung der Werkzeugkiste“ [The critical discourse analysis and the pictures. Methodological and methodic thoughts on an expansion of the toolbox], DISS-Journal 21, 2011, 14–15.

Higa Tomiko, The Girl with the White Flag. Tokyo: Kōdansha International, 1991.

Hood, Christopher, Japanese Education Reform: Nakasone’s Legacy. London: Routledge, 2001.

Jäger, Siegfried, Kritische Diskursanalyse. Eine Einführung [Critical Discourse Analysis. An Introduction], Münster: Unrast, 2012.

Jäger, Siegfried and Maier, Florentine “Theoretical and methodological aspects of Foucauldian critical discourse analysis and dispositive analysis”, in Ruth Wodak and Michael Meyer, eds, Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis, London: Sage, 2009, 34–62.

LDP [Jiyū Minshutō], Nihon wo torimodosu. Jūten seisaku 2012 [Taking back Japan. Core Policies 2012], 2012.

McNeill, David, “Back to the Future: Shinto, Ise and Japan’s New Moral Education,” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus.

McNeill, David and Lebowitz, Adam, “Hammering Down the Educational Nail: Abe Revises the Fundamental Law on Education”, The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus.

Miyake Akiko, “‘Kokoro no nōto’ no tekisuto – imēji bunseki” [Analyzing the Text and Pictures in ‘Kokoro no nōto’], Gendai shisō 4, 2003, 122–138.

MoE (Ministry of Education), Gakushū shidō yōryō [Elementary School Curriculum Guidelines], 2017.

Nakahodo Masahiko, “Okinawa-sen o meguru gensetsu: ‘shiroi hata no shôjo’ o megutte”, Nihon Tôyô bunka ronshû 15, 2009, 9–39.

Nozaki Yoshiko and Selden, Mark, “Japanese Textbook Controversies, Nationalism, and Historical Memory: Intra- and Inter-national Conflicts”, The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus.

Ōmori Naoki, Dōtoku kyōiku to aikokushin: ‘dōtoku’ no kyōkaka ni dō mukiauka [Moral education and patriotism: How to face the moral education school subject], Tokyo: Iwanami, 2018.

Repeta, Lawrence, “Japan’s Democracy at Risk – The LDP’s Most Dangerous Proposals for Constitutional Change”, The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus.

Rich, Motoko, “The Man Who Won’t Let the World Forget the Firebombing of Tokyo”, The New York Times Magazine, 9 March 2020.

Richter, Steffi, “Historical Revisionism in Contemporary Japan”, in Steffi Richter, ed, Contested Views of a Common Past. Revisions of History in Contemporary East Asia. Frankfurt: Campus, 2008.

Richter, Steffi, “The ‘Tokyo Trial view of history’ and its revision in contemporary Japan/East Asia”, in Gotelind Müller, ed, Designing History in East Asian Textbooks, London: Routledge.

Saaler, Sven, Politics, Memory and Public Opinion. The History Textbook Controversy and Japanese Society. Munich: Iudicium, 2005.

Saaler, Sven, “Nationalism and History in Contemporary Japan”, The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus.

Sankei Shimbun, Shōgakkō dōtoku kyōkasho-shea toppu ha Tōkyō shoseki to Nichibun [The share of moral education textbooks – Tokyo shoseki and Nichibun at the top], 7 November 2017.

Saotome, Katsumoto, Tōkyo Daikūshū. Shōwa nijūnen sangatsu tōka no kiroku [The Great Tokyo Air Raid. Recordings from March 10th Shōwa 20], Tokyo: Iwanami, 1971.

Sugano Tamotsu, Nipponkaigi no kenkyū [Research on Nippon Kaigi], Tokyo: Fusōsha, 2016.

Takahashi Tetsuya, “The Emporer Showa standing at ground zero: on the (re-)configuration of a national memory of the Japanese people”, The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus.

Tawara Yoshifumi, “What is the Aim of Nippon Kaigi, the Ultra-Right Organization that Supports Japan’s Abe Administration?”, The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus.

Tsujita Masanori, Monbushō no kenkyū: ‘Risō no nihonjin-zō‘ wo motometa hyaku-gojūnen [Research on the Ministry of Education: 150 years of searching for the ideal Japanese], Tokyo: Bungei shunjū, 2017.

Watanabe Michiru et al., eds, 2020, Atarashii dōtoku [New Morals]1–6, Tokyo: Tokyo Shoseki.

Yuan Cai, “The Rise and Decline of Japanese Pacifism”, New Voices 2, 2008, 179–200.

Notes

Chief among these allies are the elites of the bureaucracy, business lobby groups and right-wing grassroots organizations like Nippon Kaigi.

According to a Sankei Shimbun article, two textbook series had the highest market share in 2017 with 21.3 % each: The Tokyo Shoseki series New Morals (Atarashii Dōtoku) and the Nihonbunkyō Shuppan series Zest for Life (Ikiru Chikara) (Sankei, 2017).

The text provides no details about the demonstration or how she was able to participate in it. Higa’s book, however, describes it as a Peace March in connection with the UN General Assembly on Arms Reduction (Higa 1991, 121).

This naturally gives rise to the suspicion that the white flag might have been prepared by Japanese soldiers who used Tomiko as a human shield to be able to capitulate safely. This interpretation, however, has been rejected by Higa in the afterword of her book where she claims to have met the soldiers accidently (cf. Higa 1991, 121; Nakahodo 2009, 33).