Abstract: The Tokyo Games have had mixed success on the compactness and sustainability fronts. The financial news, however, has been uniformly disappointing. Interest groups play a clear role in prompting governments to pursue the Olympics. While the population as a whole experiences little or no net benefit, specific groups, such as the local hospitality industry and construction unions, stand to gain a great deal. These groups spend heavily to elect politicians who support their pursuit of the Olympics.

Introduction

It all seemed so promising on September 7, 2013 the day that the International Olympic Committee (IOC) awarded Tokyo the right to host the 32nd Olympiad. The Games were going to be compact – with virtually all events taking place within Tokyo – environmentally responsible, and, most of all, profitable. In its bid to the IOC, The Tokyo Organizing Committee of the Olympic Games (TOCOG) had projected expenses of $2.5 billion and revenues of $3.3 billion. The macroeconomic stimulus anticipated from the infrastructure construction and influx of tourism led some observers (e.g., Harner, 2013) to refer to the Olympics as “Abe’s Fourth Arrow,” a play on the three arrows of Prime Minister Abe’s economic revitalization plan.1

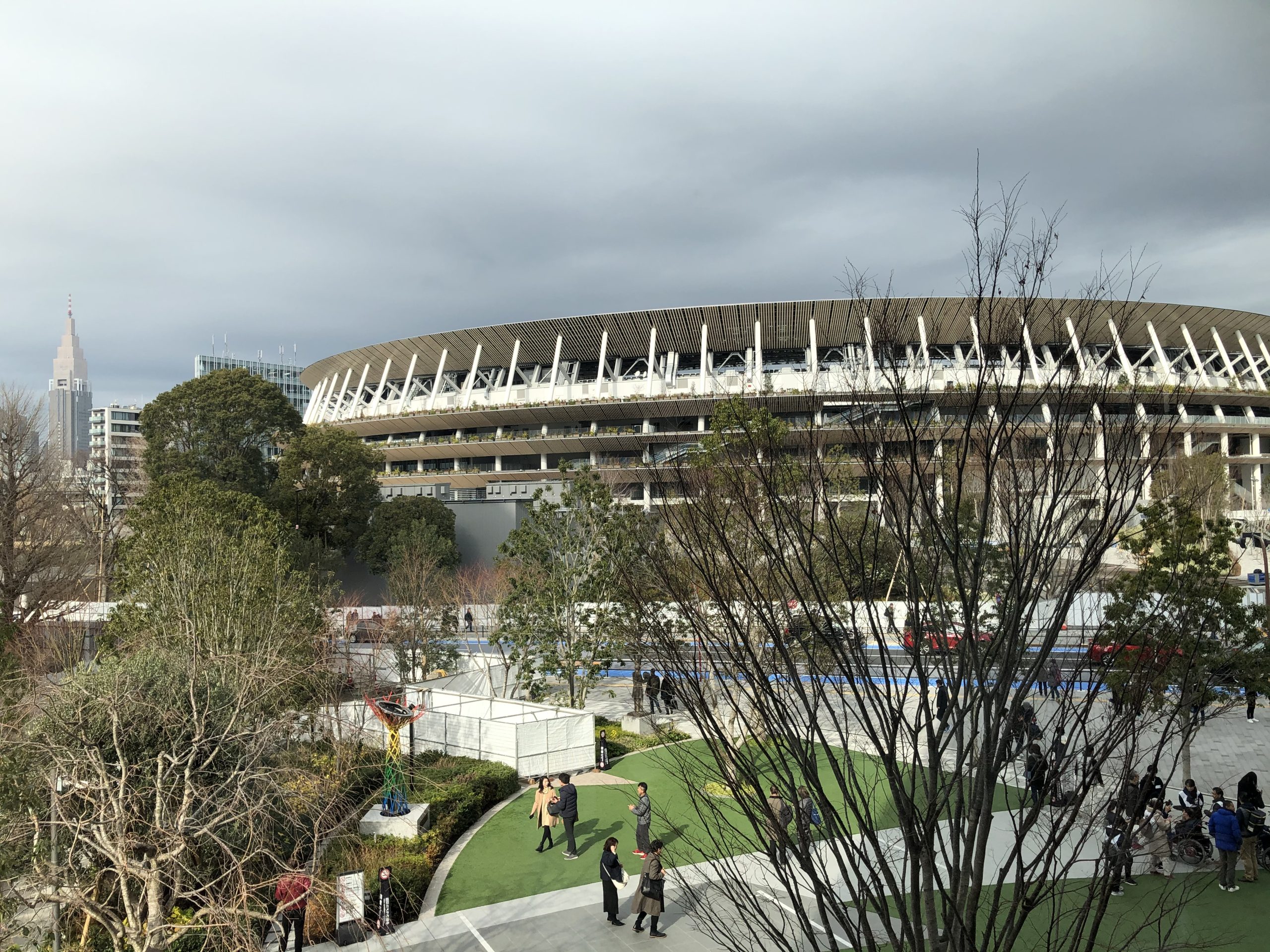

The Tokyo Games have had mixed success on the compactness and sustainability fronts. The financial news, however, has been uniformly disappointing. Despite strong advance ticket sales and better-than-expected revenue from sponsorships, costs have far outpaced revenues. Some of the problems are self-inflicted wounds. For example, the cost of constructing a new National Olympic Stadium, about $1.5 billion, is roughly 40 percent over budget and more than 1.7 times the cost of the stadium London built as the centerpiece of the 2012 Games.2 However, many of the problems that Tokyo faces are unavoidable consequences of hosting the Olympic Games.

The Winners

When asking whether the Olympics will be profitable, it is important also to ask for whom they are profitable. Of the three main participants in staging the 2020 Games, the IOC, TOCOG, and Tokyo Metropolitan Government (TMG), only the first two are sure to gain from the Games.

Although it is officially a not-for-profit organization, the IOC generates a huge amount of revenue from the Games. The revenue begins to flow even before the IOC names a host city. TOCOG, along with organizing committees from Baku, Doha, Istanbul, and Madrid, had to pay the IOC $150,000 just to apply to host the 2020 Games. Istanbul, Madrid, and Tokyo advanced to “candidate” status, which required an additional $500,000 payment per city. The IOC thus took in over $2 million just from the application process.

The IOC’s greatest sources of revenue are broadcast rights and sponsorships. The broadcast rights for the 2018-2020 Olympic cycle (which includes the much smaller 2018 Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang) should bring in over $4.5 billion. This is about $500,000 more than the preceding cycle and represents enormous growth from the $1.25 million that the 1960 Winter and Summer Games generated.

As TV revenues have risen, the fraction of revenue that the IOC shares with the local organizing committees has fallen. Finally, in 2016, the IOC switched to a flat payment of $1.5 billion to the local organizing committee. (Zimbalist, 2015 and Shirinian, 2014)

The IOC also collects the revenue from the highest level of sponsorship, “The Olympic Partner” (TOP) program. Begun in 1985, TOP generated over $1 billion in revenue for the 2013-16 Olympic cycle. The sponsors also provide an array of goods and services to the Games. The goods and services include such items as IT support from sponsors like AliBaba and Atos, tires for Olympic vehicles from Bridgestone, and personal grooming products for the athletes from Proctor & Gamble. (International Olympic Committee, 2019) In exchange, the sponsors get the exposure and branding that come with being associated with the Olympics.

The organizing committees also do quite well financially. In fact, as we shall see, it is impossible for an OCOG to lose money on an Olympics. TOCOG appears to be particularly well-situated for three reasons.

First, TOCOG has generated a record level of revenue from its domestic sponsorship program. Unlike the TOP sponsors, who are largely multinational companies with no ties to a particular host city (though Alibaba was particularly attracted by the fact that the 2018 and 2022 Winter Games along with the 2020 Summer Games would all be held in Asia), TOCOG’s domestic sponsors are largely local companies that agree to support the 2020 Games. Thus, the domestic sponsors for Tokyo 2020 include such companies as Canon at the top “Gold Partner” level, Japan Airlines at the “Official Partner” level, and Kokuyo at the “Official Supporter” level. Overall, TOCOG has generated over $3 billion in domestic sponsorships from more than 60 companies. (Grohmann, 2019) This sum is close to double the $1.6 billion that the Rio Olympics drew. Domestic sponsorships are particularly valuable for organizing committees because, unlike the money from the TOP program, revenue from domestic sponsorships stay with the OCOGs.

Second, like the organizing committees before it, TOCOG is responsible only for operating the Olympic Games. This includes the cost of staging the events and providing security for the Games. However, the agreement to host the Olympic Games specifies that host cities must “ensure the financing of all major capital infrastructure investments required to deliver the Olympic Games.” This means that all spending on building new facilities for the events or building new roads, airports, and mass transit systems for the visitors falls on the host city and country.

Because the Tokyo Metropolitan Government (or the Japanese Diet) must cover all capital expenses, the costs reported by TOCOG are only a fraction of the full cost of the Games. The distinction between operating expenses and capital expenses has often created confusion regarding the cost of Olympics. TOCOG currently reports that the cost of staging the Games will come to $12.6 billion, though Japan’s National Audit Board says that the full cost is much higher. The total cost of the Games is almost twice as high, as Japan reports public spending of close to $10 billion. (Associated Press, 2019a and JIJI, 2019)

Finally, the agreement to host the Games also specifies that any shortfall in revenue by the organizing committee must be made up by the host city. If the city cannot afford the expense, then the host country must make up the difference. It is therefore legally impossible for the local OCOG to lose money on an Olympics.

Do Cities Benefit from Hosting the Games?

With such massive expenses, it seems unlikely that cities can profit from the Olympics. Cities, however, do not regard such projects from a strict revenue and cost perspective. Indeed, doing so would be to misunderstand the role of government in the local economy. Unlike firms, local governments do not maximize profit. Instead, they have the more amorphous task of maximizing the well-being of their residents. Thus, even if a government loses money on the event itself, hosting the Olympics could still be worthwhile if it increases employment or incomes sufficiently.

At the risk of some oversimplification, I identify four ways in which a city can benefit from hosting the Olympics:

- Construction jobs

- Infrastructure improvement

- Tourism during the Games

- Legacy effects, such as branding

Construction of Facilities

The construction jobs associated with hosting the Olympics are of limited duration. They start appearing about five years prior to the Games and largely disappear by the time the Games begin. The degree of job creation is limited by two factors.

The most obvious limitation is the need for new facilities. Highly developed cities like London, Tokyo and Los Angeles, which rely heavily on existing structures, will see relatively little new construction and few additional construction jobs. Unlike the Tokyo of the early 1960s, which was transformed by the massive construction projects that accompanied the 1964 Olympics, contemporary Tokyo needs far fewer new athletic facilities and far less infrastructure investment.

Another limiting factor is the availability of unemployed labor. If an economy does not have a pool of unemployed, skilled construction workers, it will have to pull workers away from other construction jobs to build Olympic facilities. With an unemployment rate that has been below 3.5 percent since 2015, it is likely that Japan has had to reshuffle already-employed workers rather than expanding opportunities for unemployed workers.

Japan has met this shortage by importing up to 55,000 foreign workers. In addition to filling vacancies, using foreign workers has kept the pay of Japanese workers from rising due to the increased demand for labor. Foreign workers earn between one-third and one-half the wages paid to Japanese workers. (Associated Press, 2019b)

Even if the host city boosts employment from constructing new athletic facilities, such gains are effectively a “sugar high” that boosts the economy briefly but has no lasting effect, as most of the facilities have no lasting economic use. Even when a city finds a later use for a facility, as was the case when London sold its Olympic Stadium to the West Ham United Football Club, the city might not come out ahead. To make the stadium suitable for soccer, London had to spend over $350 million in conversion costs. (Gibson, 2016)

The sad fact is that most Olympic facilities go unused after the Games. Beijing’s “Bird’s Nest,” constructed for the 2008 Games and hailed as an architectural marvel, is now an empty “museum piece” that requires $11 million in annual upkeep. (Weissman, 2012) If the host city fails to maintain the facilities, they can quickly become eyesores, as happened with Greece and, more recently, Brazil. Mane Garrincha, built at a cost of $800-900 million for the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Olympics, is the second most expensive soccer stadium in the world. After hosting seven World Cup matches (including a quarterfinal game) and ten Olympic matches, the 72,788-seat stadium now serves as the world’s most expensive bus depot in Brasilia. (Douglas, 2015)

Infrastructure Improvement

Fortunately, cities often build much more than stadiums when they host the Olympics. New or improved airports, roads, and mass transit systems all have lasting effects on the host nation’s economy. Rio de Janeiro, for example, promised its residents a wide array of public improvements, ranging from airports to roads to the city’s power grid. (Genasci, 2012)

Indeed, one of the main justifications for hosting the Olympics is that it focuses a nation’s attention on infrastructure improvements that it should be making but might not otherwise have the political will to implement. Again, however, the benefits from infrastructure can be limited.

As with stadium construction, some cities, particularly from wealthy countries, might not need much additional or updated infrastructure. Poorer countries, such as Greece or Brazil, often have such a hard time financing the sports facilities that they cannot make good on the promised investments in other goods. Brazil was in such financial straits that even essential government services had to be curtailed. (Gomez, 2016) In addition, much of the transportation infrastructure is often oriented toward transporting people to Olympic venues. Such investment is of limited value to the general population once the Games are over.

Tourism

With hundreds of thousands of visitors coming from all over the world, the one certainty would seem to be that tourism thrives during the Olympics. Indeed, it seems to be a matter of simple arithmetic. Tokyo expects 600,000 tourists for the Olympic Games. (Richarz, 2019) If, on average, each tourist stayed in Tokyo for 10 days and spent $500 per day, then the Olympics should generate $3 billion in tourist spending.

Unfortunately, arithmetic must give way to economics. To figure out the net impact of Olympic tourism, we must first account for the fact that Olympic tourists crowd out other tourists. Both organized meetings, such as conferences, and individual visits are cancelled or re-directed for the duration of the Games.3 The net result is that, at best, host cities typically see modest increases in tourism, as was the case for Vancouver in 2010 and Rio in 2016. Often, however, they experience a decline in tourism during the Olympics, which happened for Beijing in 2008 and London in 2012.

Moreover, Olympic tourists differ from other tourists. Rather than visit historical or cultural centers, they focus – and spend their money – on a very narrow set of goods and activities centered on the Games. This leads to windfall profits for food and memorabilia vendors in the immediate vicinity of the Olympic venues. However, the lack of interest of Olympic tourists in the broader culture and economy of the host city and country, combined with disrupted travel patterns, often creates significant hardships for other merchants.

Given the high costs and the limited benefits, it should not come as a surprise to learn that very few economic studies find large or lasting impacts on host cities. Of eight studies surveyed by Baade and Matheson (2016), only one – for the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta – find a strong positive impact on the local economy (Hotchkiss et al. 2003), and even that finding has been challenged by a later study (Feddersen and Maennig, 2013). In sum, the short run impact of hosting the Olympics appears to be short and fleeting. That has led advocates to turn to the long-term benefits of the Olympic legacy.

The Olympic Legacy

Advocates claim that hosting the Olympics continue to bring benefits long after the flame has been doused. They point to increased tourism and media exposure as important tools for reshaping a country’s “brand” and making it more attractive for both tourists and investors. Many host countries have used the Olympics as a “coming out party” to announce themselves to the world. In some cases, the purpose can be political, with the host country staking its claim to be a world power, as was the case for Germany (1936), China (2008), and Russia (1980 and 2014). In other cases, such as Japan (1964), South Korea (1988), or Spain (1992), the host countries have used the Games to declare themselves as open for business, be it tourism, trade, or investment.

Of course, international attention can be a two-edged sword. In addition to all the positive feelings generated by the 2008 Olympics, the Beijing Games also brought the repression of Tibet and China’s severe environmental problems to light. (See, for example, Ramzy, 2008.) Similarly, the news reports that accompanied the 2016 in Rio were just as likely to feature corruption, violence, pollution, and the Zika virus as they were to focus on hot tourist spots. (Zimbalist, 2017)

The different nature of Olympic tourism also limits the tourism legacy. With their narrow focus on the athletic events, visitors during the Games can say little about the host country that would make others want to visit. Unfortunately, according to the European Tour Operators Association, such “word of mouth” is the single biggest spur to tourism. (Zimbalist, 2015). Thus, even the modest bump in tourism quickly dies away.

Barcelona is the major exception to this general rule. Prior to the 1992 Games, Barcelona was largely an afterthought among tourists, ranking a distant second to Madrid as a tourist destination in Spain. Since the Games, it has become the fifth most-visited city in Europe. (Baade and Matheson, 2016) While the Olympics might have spurred Barcelona’s tourism and development, the city benefitted from a confluence of forces that coincided with the Olympics.

First, like the rest of Spain, Barcelona benefited from the country’s return to democracy in the late 1970s after four decades of fascist rule. Further, Spain’s joining the European Union in 1986 helped spur two decades of economic growth. The impact of these events was particularly strong in Barcelona, which, as a center of opposition to the dictator Francisco Franco, suffered decades of repression and neglect.4

Second, the 1992 Olympics were part of a larger plan for the city’s development. The city used existing facilities wherever possible and constructed new facilities with post-Olympic usage firmly in mind. This enabled Barcelona to focus on non-sports infrastructure, which constituted 83 percent of investment spending prior to the Games. (Zimbalist, 2015) This stands in stark contrast to other host cities.

Even if tourism fades, the Olympics could still provide a positive legacy if, as some claim, it signals to the outside world that the host country is opening its economy to trade and investment. (See, for example, Rose and Spiegel, 2011.) Indeed, it is true that countries that have hosted an Olympics enjoy greater trade and foreign investment than countries that have not been hosts. However, it is also true that host countries, being generally wealthy with highly advanced economies, also experienced greater trade and investment before the Games took place. Once one accounts for an economy’s “openness” prior to the Olympics, no relationship between the Olympics and international economic engagement appears to exist. (See Billings and Holladay, 2012; and Maennig and Richter, 2012.)

Why Do Cities Bother?

If hosting the Olympics provides limited, short-term benefits, why do cities bother going to the expense and trouble of hosting the Olympics? One possible explanation comes from the behavior of interest groups. An interest group is a relatively small collection of people that stands to gain a great deal interest from a specific policy. While most voters may be harmed by the policy, they do not have an incentive to oppose the interest group because the harm done to any individual is relatively small, while the gains are highly concentrated. The existence of interest groups helps explain why national governments impose tariffs that raise the prices that consumers pay but help protect specific businesses and workers.

Interest groups play a clear role in prompting governments to pursue large-scale events, such as the Olympics. While the population as a whole experiences little or no net benefit, specific groups, such as the local hospitality industry and construction unions, stand to gain a great deal. These groups spend heavily to elect politicians who support their pursuit of the Olympics. Other voters do not share the interest groups’ laser-like focus and often fail to make their voices heard.

While the influence of interest groups remains powerful, opposition to spending money on the Olympics has grown in recent years. This has caused he number of applicants to decline steadily. (Zimbalist, 2015) It has also affected the types of countries that bid to host the Games. The bidding process for the 2022 Winter Games yielded only two applicants, Kazakhstan and the People’s Republic of China, neither of which is a paragon of democracy. Without significant reforms, future Olympics my increasingly be hosted by despotic countries whose rulers are willing to spend freely for their own satisfaction.

References:

Associated Press. 2019b. “Rights Group Asks for Worker-Safety Probe at Tokyo Olympics,” USA Today, June 7.

Billings, Stephen and J. Scott Holladay. 2012. “Should Cities Go for the Gold? The Long-Term Impacts of Hosting the Olympics,” Economic Inquiry, 50(3), July: 754-772.

Douglas, Bruce. 2015. “World Cup Leaves Brazil with Bus Depots and Empty Stadiums,” BBC Sport, March 29.

Feddersen, Arne and Wolfgang Maennig. 2013. “Mega‐Events and sectoral employment: The case of the 1996 Olympic Games,” Contemporary Economic Policy, 31(3), July: 580-603.

Genasci, Lisa. 2012. “Infrastructure: Brazil, the World Cup, and Olympics,” Americas Quarterly, Fall.

Gibson, Owen. 2016. “West Ham Olympic Stadium deal explained: From Water City to London Stadium,” The Guardian, November 2.

Gomez, Alan. 2016. “Rio Government Declares “Public Calamity” over Finances in Advance of Olympics,” USAToday, June 17.

Grohmann, Karolos. 2019. “Tokyo 2020 Games Domestic Sponsorship Tops $3 Billion as Companies Pile in,” Reuters, June 25.

Harner, Stephen. 2013. “The 2020 Olympics: A ‘Fourth Arrow’ for Abenomics and a Second Term for Abe,” Forbes, September 10.

Hotchkiss, Julie, Robert Moore, and Stephanie Zobay. 2003. “Impact of the 1996 Summer Olympic Games on Employment and Wages in Georgia.” Southern Economic Journal, 69(3), January: 691-704.

International Olympic Committee. 2011. 2020 Candidature Acceptance Procedure, Lausanne: IOC.

International Olympic Committee. 2019. The Olympic Partner Programme.

JIJI. 2019. “Japan Has Spent over ¥1 Trillion on Tokyo Olympics and Paralympics So Far, Audit Reveals,” Japan Times, December 6.

Leeds, Michael A. 2008. Do Good Olympics Make Good Neighbors? The Impact of the 2002 Salt Lake City Olympic Games on the Colorado Economy. Contemporary Economic Policy, 26(3), 460-467.

Maenning, Wolfgang and Felix Richter. 2012. Exports and Olympic Games: Is There a Signal Effect? Journal of Sports Economics, 13(6), December: 635-641.

Owen, David. 2015. “Exclusive: IOC Set to Generate Record $4.5 Billion from Pyeongchang 2018 and Tokyo 2020 TV Rights,” Inside the Games, July 14.

Ramzy, Austin. 2008. “Beijing’s Olympic War on Smog,” Time, April 15.

Richarz, Allan. 2019. “What You Need to Know: The Tokyo 2020 Olympics,” New York Times, November 11.

Shrinian, Zjan. 2014. “Rio 2016 ‘Top Priority’ after World Cup, Pledges Brazilian President,” Inside the Games, July 11.

Wade, Stephen and Mari Yamaguchi, 2019. “Tokyo Olympics say costs $12.6B; Audit report says much more,” Associated Press. Dec. 20.

Weissman, Jordan. 2012. “Empty Nest: Beijing’s Olympic Stadium Is an Empty ‘Museum Piece,’” The Atlantic, July 31.

Zimbalist, Andrew. 2015. Circus Maximus, Washington, DC.: Brookings Institution Press.

Zimbalist, Andrew. 2017. The Economic Legacy of Rio 2016, Rio 2016. Edited by A. Zimbalist, Washington D.C.: Brookings Institution Press.

Notes

This is far cheaper than the initial stadium design, whose estimated cost was well over $2 billion.

Ironically, sport was a popular form of resistance, as supporting FC Barcelona became a way to express anti-Francoist sentiments, particularly since Franco was a fervent fan of Réal Madrid.