Abstract: This is a memoir about the hectic preparations for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics that proved to be a successful coming out party. For the Japanese, the success of the games was a source of pride. The world discovered a new Japan, one that was no longer a shunned militarist rogue regime but rather a peaceful democracy on its way to becoming a world economic powerhouse. For the citizens of Tokyo, the Olympic success was doubly important because their city was now rebranded as the capital of cutting-edge technologies.

I first arrived in Tokyo in January 1962 as a 19-year-old GI, when the city of Tokyo was in the midst of an historic transformation. The unsightly urban sprawl of rickety wooden houses, scabrous shanties and cheaply constructed stucco covered buildings that had mushroomed out of the rubble left by the American B-29 Superfortress bombings, was now being razed to the ground and in its place a brand-new city was going up. Thousands of office and residential buildings were under construction, along with several 5-star hotels and an elevated expressway network. Also being built were two new subway lines to go with the two that already existed, a multi-million dollar monorail from Haneda airport into downtown Tokyo, and a billion dollar 130-mile-per-hour bullet train between Tokyo and Osaka.

The effort to redo Tokyo’s urban infrastructure was undertaken in conjunction with a massive government plan to double GNP and per capita income by the end of the sixties through the manufacture and export of transistors, radios, television sets and automobiles. But it was made all the more urgent in 1959 when the city was awarded the 1964 Olympics, the first Asian country to be so honored.

Tokyo was already the single most populated city in the world, with residents exceeding 10 million as of 1962, more than doubling since the end of war. Thousands flowed into the city every day, many of them on shudan-sha, trains dedicated to carrying groups of job seekers, many of them teenagers fresh out of provincial junior high schools destined for the city’s factories and numerous construction sites.

The pace of life in the city was dizzying. There was, however, a lot to do to bring the city up to western standards. Living conditions were still largely primitive in most areas outside the main hubs. The harbor and the capital’s main rivers were thick with sludge from the human and industrial waste that poured into them and drinking local tap water, we were told, was unsafe. Decades later, Tokyo would be justifiably famous for its high-tech toilets, with their automated lids, music modes, water jets, blow-dry functions and computer analyses, that headlined an impressive sewerage system. But back then, despite the frantic rebuilding, less than a quarter of the city’s 23 sprawling wards had flush sewage systems at all, making Tokyo one of the world’s most primitive (and odiferous) megalopolises. Fecal matter had to be sucked out from under buildings by the kumitoriya vacuum trucks and then transported to rice paddies for use as fertilizer.

Tokyo was also rat-infested and some 40% of the Japanese had tapeworms. There were no ambulances and infant mortality was 20 times what it is today. Moreover, house theft was rampant, narcotics use was endemic, and it was considered too dangerous to walk in public parks at night. Yakuza were everywhere, their numbers at an all-time high.

Tokyo’s winning bid was fueled by an ambitious half-billion dollar budget to re-make the capital for the event, a figure that far exceeded the $30 million spent for the Rome Games in 1960. It was also facilitated by intensive wining and dining of the Olympic Committee during a visit to the capital in 1958 that reportedly included Tokyo’s finest call girls. After winning the games in 1959, however, the question many people had was, “How in the world is the city ever going to be ready in time?”

Countdown

The two shiny new subway lines had opened up— Toei Asakusa (1960), and Hibiya (1961), joining the older Ginza (1927) and Marunouchi (1954) lines—but as late as January 1963 none of the target dates for road construction had been met and the government conceded that Olympic preparations were “regrettably” behind in all aspects.

Construction on the newly elevated coastal highway leading from Haneda Airport some 13 miles into the capital was late getting started because fishermen owned long stretches of the land along the intended route and were demanding multiples of the price the government had anticipated paying. Moreover, speculators had bought up large plots of land the government needed for a second inland expressway into the city and demanded exorbitant prices. There were eminent domain laws on the books, but the government was obligated by legal precedent to pay the full asking price, and in these cases the asking price was simply too high. Further complicating the matter was the fact that the families of those owners and residents who had decided to sell, and who numbered in the thousands, had to be moved to other accommodations in the capital and such accommodations were not always easy to find in land scarce Tokyo.

An even bigger problem looming ominously over the city was a dire shortage of water in the capital caused by an abnormal lack of rainfall in the wet season preceding the 1964 Games. Tokyo’s reservoirs had been emptying for three months and as the summer began, the municipal government instituted water rationing. Bathhouse hours were restricted, swimming pools closed and on narrow side streets, police water trucks, usually employed to quell leftist riots, filled housewives’ buckets with water hauled in from nearby rivers. Soba shops cut down on their cooking, while Ginza nightclubs urged thirsty patrons to “drink your whiskey without water and help save Tokyo.”

Drilling crews dug emergency artesian wells while other work crews excavated canals to bring in water from nearby rivers. Japan Self-Defense Force planes dumped dry ice on overhead clouds, while on the shores of the Ogochi reservoir outside the city a Shinto priest in the mask of a scarlet lion writhed through a ceremonial rain dance. Townsmen were warned not to expect miracles. As the priest explained, “It will take two days for the message to get through to the dragon god.”

As the deadline for the Games approached, (sensibly they had been shifted to October because of Tokyo’s oppressive summer heat) there was an enormous, frantic rush to finish everything on time. Construction continued around the clock, seven days a week. Bulldozers rearranged the landscape and dump trucks loaded up with dirt for land reclamation projects in Tokyo’s fetid harbor rumbled back and forth in unbroken streams.

At night, after the salarymen had gone home and the traffic thinned out, the city stepped up construction. Blinding work lights and diesel compressors switched on, traffic on Tokyo’s main thoroughfares was rerouted, and new sets of air hammers and pile drivers were put to work opening up those streets. This went on until dawn when the avenues were covered with temporary wooden planks and traffic resumed. Most of Tokyo’s citizens stoically put up with the annoyances, using black curtains and earplugs to block out the light and noise. I did the same when I stayed overnight in the city. But I clearly remember a newspaper item in one of the English language dailies about a college student who was unable to study because of the constant pounding near his rooming house and became so agitated that he marched down to the construction site, put his head underneath the offending pile driver and ended his misery.

Three months before the games were scheduled to begin, glimpses of the New Tokyo began to appear, including long finished stretches of the raised expressways. You could even take a ride on a section of the new overhead highway from Shimbashi to Shibaura for ¥50 (about 15 cents) and many people did just that to see what it was like, including me, with a new acquaintance, a Dr. Sato who took me along for a spin on the two mile run in his brand new Nissan-Z Fair Lady roadster (his “weekend car” as he put it) , oohing and aahing at the smoothness of the road, while listening to I Wanna Hold Your Hand, by a new group called the Beatles, on the radio.

“I like the smell of freshly dried asphalt, ” he exclaimed, “It means progress.”

Bullet Train

The much-ballyhooed Monorail from Haneda International Airport into Tokyo began operations on September 17, 1964; it would go on to become the busiest and most profitable monorail line in the world. On October 1, ten days before the Games were scheduled to begin, the putative crown jewel of the Olympic effort, the Japanese bullet train, started operations between Tokyo and Osaka. The Shinkansen, the fastest train in the world, transported its passengers 320 miles in about four hours. The train followed the picturesque route of the old Tokaido Line, along the earthquake-prone Pacific coastline. The New Tokaido Line would become the busiest commuter corridor in the world, busier even than the one that ran between New York and Washington D.C. The trains’ arrival and departure times were so reliable that people could set their watches by them, the average delay being half a minute.

During this period the wraps were taken off the last of the gleaming new buildings constructed in the center of the city, among them the glamorous Hotel Okura–modeled after an ancient Kyoto temple, the 17 floor Hotel New Otani built next to a 400-year-old garden, and now the tallest building in the city with Tokyo’s first revolving roof, and the 1,600 room Shiba Prince Hotel. To meet construction deadlines, the Otani builders and the Toto Corporation (the world’s largest toilet manufacturer) developed the unit bathroom: toilet, sink and bathtub in one neat box installed by crane from the outside. Then one after another, the athletic fields, arenas and halls to be used in the Olympiad were completed. They included the space age Olympic Park complex for volleyball and soccer; the winged Budokan for the martial arts; the National Stadium for track and field; and Kenzo Tange’s swooping, wave shaped National Gymnasium complex for swimming and diving. Melding modern engineering techniques with traditional Japanese forms, Tange’s work would later win the Pritzker Prize for architecture, while the stadiums he designed remain iconic landmarks of Tokyo.

Of special significance to the Japanese was the completion of the Olympic Village, a renovated complex that had housed U.S. military officers and their families since the end of the war and would now host the 6,624 athletes and their coaches and trainers during the Games. The area, then known as Washington Heights, was located next to the Meiji Shrine and had been the site of a barracks and parade ground for the Japanese Imperial Army before the war.

But not quite everything was finished, including six of the planned expressways, as well as a fleet of mobile public toilets the government ordered at the last minute. In an effort to put a stop to the common male practice of relieving themselves on side streets, signs in the subways were put up that said, “Let’s refrain from urinating in public.”

Foreign Wave

A full week before the October 10th Opening Ceremony, Olympic athletes began arriving at Haneda Airport – the Russians on Aeroflot, the Americans via Pan Am, the British via BOAC – with welcoming press conferences arranged right on the tarmac. Along with the athletes came the first waves of international tourists. Many Japanese said they were seeing gaijin for the first time in their lives.

The transformed city was almost unrecognizable compared to what it was when I first arrived in 1962. Construction had halted and everywhere you looked, you saw a glistening new building. There were flags all over the city honoring the 94 nations participating in the games – 7,000 of them said the papers, each one of them tended to by a Japanese boy scout. The Hotel Okura displayed the flag of every participating nation outside its main entrance

Menacing yakuza had virtually vanished from the streets. At the request of the government, gang bosses had ordered the more “unpleasant looking” mobsters in their ranks to leave the city for the duration of the Games and undergo “spiritual training” in the mountains or seashore. The beggars and vagrants who had occupied Ueno Park and other parts of the city, had also magically disappeared, as had the streetwalkers who normally populated the entertainment areas. As an added bonus, the city’s 27,000 taxi drivers had been persuaded by the authorities to stop honking their horns, all in the interests of making Tokyo sound as sedately refined as a temple garden hung with wind chimes. At many intersections, there were containers of yellow flags, put there for pedestrians to use while crossing the street, a necessity given the humongous traffic jams that clogged Tokyo’s main avenues.

The citizens of Tokyo had been trained to accord the highest courtesy and hospitality to the athletes, officials, journalists and spectators who converged on the capital. Smiling interpreters, organized by the municipal government, roamed the city in special cars, searching for bewildered looking foreigners to help – and they were not hard to find. In the Ginza, at the big shrines like Meiji Jingu, at cafes, clubs and restaurants, there was never a shortage of loud talking foreign tourists anxiously poring over their guidebooks and maps, attempting to decipher Japan’s arcane address system. During that time, I found it nearly impossible to walk down a street in any of the main shopping and entertainment areas without being stopped by someone and asked if I needed help finding my destination.

Even when no volunteer raced up to offer you guidance, it was still hard for the foreign visitor to get lost. No matter where you were, on the sidewalk, at the train station, in Japan’s labyrinthine underground pedestrian walkways, there were signs posted in English pointing the way.

There were also signs in Japanese reminding the citizenry to be on its best behavior, along with others warning young girls not to be taken in by the lady-first etiquette practiced by foreign men. “Do not mistake this as an expression of love” said one that I remember with particular fondness.

On October 9th, one day before the start of the games, as if ordained by the Shinto gods, a heavy rain visited Tokyo and washed away all the dirt and dust and air pollution, cleansing the city for the big event.

Opening Ceremony

The opening ceremony was presided over by Emperor Hirohito, the man in whose name the attack on Pearl Harbor and the invasion of Southeast Asia were undertaken by the Japanese Imperial Army some 25 years earlier. Back in 1946, General Douglas MacArthur, head of the Allied occupation forces, ensured Hirohito wasn’t prosecuted but he did have to renounce his divinity and relinquish all political power. He appeared not as the head of state as normally required by the IOC, but in his capacity as “patron” of the Tokyo Olympics, to use the term concocted by the Organizing Committee with the assistance of the Ministry of Education.

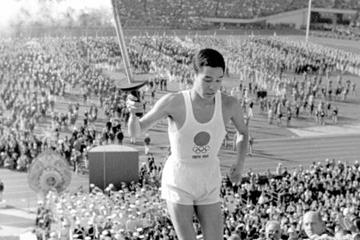

He stood there in a special box wearing a simple black suit, a thousand riot police guarding the grounds outside, as the athletes marched into the new National Stadium before a crowd of 75,000: American athletes in their big cowboy hats, Indians in purple turbans, Ghanaians in saffron robes, and the Japanese contingent, coming in last, in red blazers and white slacks, carrying the Hi No Maru flag (red disc centered in rectangular white banner), which was, along with the Emperor, another symbol of Japan’s Imperial past. Trumpets blared and cannons roared as Yoshinori Sakai, a 19 year old student athlete born in Hiroshima just hours after the atomic bomb fell on the city (and dubbed the “Atomic Bomb Boy” by the press), carried the Olympic torch up a flight of 179 steps to deposit it in its cauldron, the five-ring Olympic logo on his white T-shirt set fashionably beneath the red disc logo of the Rising Sun. Takashi Ono, a Japanese gymnast, took the athletes oath on behalf of the 5,151 participating athletes—4473 men and 678 women.

Through it all the emperor stood there alone, a diminutive 5’2”, looking for all the world like a neighborhood accountant without his wartime military uniform, medals and white stallion, watching with a demeanor that was notably more respectful than imperial. The Chicago Tribune’s Sam Jameson, who sat in the press box on the other side of the stadium, later wrote, “I don’t think I ever saw the Emperor being the only person standing before that. I imagined in my mind that he was thanking the world for re-admitting Japan into international society.”

The broadcast of that opening ceremony, on October 10, 1964, which ended with the JSDF (Japan Self Defense Force) aerobatic skywriting team Blue Impulse tracing the five rings of the Olympic symbol in the sky with their F-86 Sabre Jets (without the benefit, one might add, of an electronic guidance system for the pilots), was watched by over 61.2% of the viewing public in Japan, and was the first such Olympic event to be telecast live internationally. It was also the first to be telecast in color.

The only thing that marred the event was the release of eight thousand doves from their cages. Intended as a symbolic finale for peace and friendship, the spectacle instead rained droppings on the athletes, causing them to run their fingers through their hair in disgust—except for the Americans who were thankful they were wearing those big hats.

+++

The Olympics were a resounding success, making worthwhile, in just about everyone’s opinion, the preceding chaos. Japan had originally been designated as hosts of the 1940 Olympics, but when war appeared on the horizon, the event was cancelled. Now, after 24 years of catastrophic events, Tokyo came to host the first Olympic games in Asia, and all sorts of records were set. They were the first Games in Olympic history that used computers to keep results, introducing new electronic timing devices. Innovations included a photo finish using an image with lines on it to determine the sprint results. Such advances thrust Japan into the forefront of global technological development, literally overnight.

The Olympics put the Seiko Watch company, the official timekeeper of the Games, on the map.

++++

For the Japanese, the success of the games was a source of pride. The world discovered a new Japan, one that was no longer a shunned militarist rogue regime but rather a peaceful democracy on its way to becoming a world economic powerhouse. The coming out party rehabilitated Japan ensuring it was now welcome in the global community. For the citizens of Tokyo, the Olympic success was doubly important because their city was now rebranded as the capital of cutting-edge technologies.

Validation came from the James Bond franchise choosing Tokyo the following year for what would become one of its most famous films, You Only Live Twice. The Hotel Otani would appear as the Osato Chemical and Engineering Co. Building, Tokyo headquarters of the infamous SPECTRE. Also featured were the adjoining garden, as well as the Tokyo subway system, the Kokugikan sumo hall and the neon-lit Ginza nightscape.

Shadows

If for some the Olympiad was a blaze of glory, it also cast some shadows. The 1964 Olympics may have been one of the greatest urban transformations in history but there was also a substantial price to pay.

The Games were in fact responsible for a great deal of environmental destruction and human misery in the city and its environs, as I can attest to as one who was there and paid attention to what was going on.

There was absolutely no reason to build a high-speed train connecting Tokyo to Osaka just for the Games, since there were no events taking place in Japan’s second largest city. Yet the Shinkansen project was rushed through by JNR executives in the name of “urban improvement.” The goal was to impress the rest of the world with the high level of Japanese technological achievement, as the global media focused on the Tokyo Olympiad. Thanks primarily to the haste (and also to dirty politics and graft), the project wound up costing a billion dollars, twice what the original budget called for (and roughly one-third the total cost of the Games) and the JNR president was compelled to resign.

The funds diverted to cover the expanding costs of the Shinkansen took money away from other projects, like the Monorail, which had originally been intended to link Haneda Airport to the city center. Instead it wound up terminating in sleepy Hamamatsucho, a less convenient location far from the top hotels. There was simply not enough capital to buy the land and extend the line to a more logical location like Tokyo Station or Shimbashi.

Moreover, in order to avoid buying expensive privately-owned land for the Monorail, its builders constructed it over water on a route provided gratis by the municipal government, covering the rivers, canals and sea areas below with landfill and concrete in the process. Fishing permits held by local fishing cooperatives in these districts were revoked by City Hall and many local fishing jobs were lost. A seaweed field in Omori in the city’s Ota Ward from which a prized delicacy, Omori Nori, had been harvested since the Edo era, simply disappeared.

The lack of funds for land purchases affected highway construction as well, as it also became necessary to build overhead expressways above the existing rivers and canals. Among the many eyesores that resulted from this arrangement was the covering up of the iconic Meiji-era bridge at Nihonbashi, an historic terminus for the old Tokaido Road footpath to the economic center of the old city – and the zero point from which all distances are measured in Japan.

I remember taking a walk along the canal to see the famous bridge, shortly before the Games began. I was dismayed to see its once charming appearance was completely ruined by the massive highway just a few feet overhead, like a giant concrete lid, obliterating the sky.

The reconstruction effort for the Olympics cost Tokyo much of its navigable waterways and put an end to what had been a vibrant, commercial river culture in and around Nihonbashi. By planting the support columns of the highways and other structures in the water below, many river docks were rendered useless, costing even more jobs. Water stagnated, fish died and biochemical sludge, known as hedoro in Japanese, accumulated. Tokyo’s estuaries, many of them already polluted with industrial waste and raw sewage, increasingly became putrid cesspools. Some were simply buried with debris from construction and the tearing down of WW2 era structures. Others were filled with concrete and turned into roads.

Then there were the highways themselves, clogged as they were with stop-and-start traffic. As Chicago Tribune correspondent Sam Jameson put it, “Building an expressway system based on a mathematical formula of a two-lane expressway merging into another two-lane expressway to create…a two-lane expressway was not the smartest thing to do. It guaranteed congestion. The system had to have been designed by someone who had never driven.”

Yet another adverse effect of the Olympic effort was the depopulation of residential areas. In individual cases where cash payment offers or appeals to patriotism, failed to persuade residents to vacate their homes to facilitate Olympic construction, government officials resorted to tax harassment, public shaming or investigating minor violations. The inhabitants of more than 100 houses near the Olympic Stadium site were forced to move in order to make way for the Stadium and a surrounding car park. The greenery that covered the area was removed and a nearby river buried in concrete. Among the hardest hard-hit areas were Bunkyo and Chiyoda Wards, in the center of the city, where many small single-family residences were razed, residents relocated to charmless New Town housing developments outside the city featuring massive Soviet-style apartment complexes known as danchi.

Another casualty of the 1964 Olympics were the trolley lines, which had been a cheap, reliable and pleasant way of getting around the city. With their dedicated traffic lanes, they were the most dependable passage through the traffic congestion.

But some things haven’t changed. Tokyo remains sweltering in the summer. Thus, when PM Abe assured IOC delegates that Tokyo’s summer weather is balmy, I couldn’t help but chuckle. Steamy is the new balmy. Taking pity on the athletes, the IOC moved the marathon and race walking to far balmier Sapporo where they and spectators won’t melt. Back in 1964 there were quite a few cases of heat stroke even in October, but subjecting guests to Tokyo’ summer furnace was an unthinkable discourtesy.