Abstract: The Meiji era (1868–1912) marks the initial process of Japan’s passage into modernity through Westernization, and its identification as a modern nation-state. As part of the process of identifying with European discourses, of altering its position in Asia, and of adopting Western models and values, Japan changed its political, social and cultural dispositions towards industrialization and capitalism, as well as towards nationalism and colonialism, cultural and artistic creation.

Over the course of modernization, and of adapting various Western discourses on science and culture, Japan accepted several new approaches, especially those setting Europe apart and above from the rest of the world. As a result, Japan saw the rise of racial discourses, which eventually contributed to the state’s imperial expansion into Asia.

Japan’s path to modernity was a twofold movement: on one hand, it was an internal struggle for association with Western civilizations and adoption of their modernity. On the other hand, Japan sought to conceptually distance itself from Asia, only to return a few decades later as a conquering and imperial power. In the Japanese imagination, European cultures served as a perfect model for its own reformation, yet, at the same time, Japan found itself on a pendulum movement between Europe and Asia. Japan distanced itself from what it perceived as a primitive, underdeveloped region and its cultures, while simultaneously seeking to include China and India in its vision of a unified Orient, a stronghold of Asian cultures positioned against the Occident. Ultimately, Japan’s self-definition came about through the notion of Otherness: the concept of “Japan” was defined primarily against the background of European civilization, but also, against a range of other cultures, including China and the United States, as well as its own immediate past of Tokugawa Japan.

In the first stage, the primary task was to set Japanese culture apart, and essentialize “Asia” as its Other. The desire to associate Japan with the West then led to a sense of Japan’s “inferiority” (especially in terms of technological and scientific achievements), at the same time that Japanese leaders adopted a Western position in claiming “superiority” over Asia. The double movement of association (with Europe) and disassociation (from Asia) produced a new subtext to the binary opposition between the advanced and sophisticated, versus the primitive and simple-minded. This double movement, much like the binary logic that drove Western colonialism, laid the foundations for racial ideologies and imperial practices in Hokkaidō and Ryūkyū, Korea and Taiwan, Manchuria and China, as well as the South-Pacific Islands and Southeast Asia.

The articles in this issue look at the roots of the discourses on race in the Meiji era, in tandem with the Japanese empire’s development in the latter part of the 19th Century. These concepts of race and empire lay at the center of Japan’s racist ideologies and imperialist fantasies, and now serve as the focus of our discussions.

Keywords: Race, Empire, Meiji Japan, Modernity, Capitalism, Industry, Colonialism, Imperial Japan

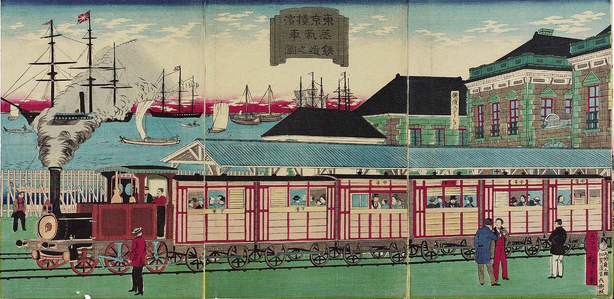

Figure 1: Hiroshige III (1842-1894) Illustration of the Steam Train Railroad between Tokyo and Yokohama「東京横濱蒸氣車鉄道之圖」Woodblock print (nishiki-e), ink and color on paper Vertical ōban triptych; 36.5×72 cm. @ Jean S. and Frederic A. Sharf Collection, Museum of Fine Art, Boston.

2018 marked the 150th anniversary of the Meiji Restoration, and Japan’s embarkation on the road of intensified modernization. This process entailed continuous adaptation of European and American practices, values, norms, ideologies and technologies. On the occasion of the sesquicentennial celebration, we had the enormous pleasure to organize the Israeli Association of Japanese Studies (IAJS) Thematic Conference, which commemorated this crucial moment in Japanese history and its impact, still felt today, on the course of Japanese history, lives and events. The conference took place at Tel Aviv University under the title The West in Japanese Imagination/ Japan in Western Imagination, and its purpose was to look at the cultural, political, societal, and artistic exchanges that accompanied the process of modernization.

As part of its mobilization and development, Japan faced the rise of newly adopted discourses and practices, which included the shift into industrialization and capitalism, the emphasis on scientific research and academic knowledge, and the fortification of nation-state and national sentiment as leading political discourses, which eventually became associated with imperialism and colonialism. Imperialism is often understood as the acquisition of lands for power and economic growth, driven by the need for extra land to support and boost agricultural and industrial processes, namely, by exploiting raw materials and other resources from conquered lands. On the other hand, colonialism is a process where the inhabitants of the colonized lands are forced to adopt the rulers’ ideologies, culture, practices and purposes.

With industrialization taking firm hold in Japan, and capitalist practices informing the main financial and social approaches across government and financial institutions, other ideologies such as nationalism and colonialism – the latter a process initiated in the late days of the Edo period (bakumatsu) – gradually took root, linking modernity with the signs of the newly formed nation-state, and justifying expansion into territories overseas. There was one more important aspect that fueled the process of modernity (with its attendant processes of nationalism, colonialism, industrialization/capitalism): with scientific and historical research at its core, racism became the accepted logic of political acts and practices, separating human beings under racist values and categorizations. Europe, in particular, fostered a sense of superiority as the “white man” over the “natives” of colonized lands in Asia, Oceania, Africa and America – an attitude that went hand in hand with the massive amounts of power and greed behind capitalist, nationalist and imperialist practices, and that was subsequently endorsed by cultural, racist worldviews justifying exploitative practices across colonies under European colonial power. These worldviews made much use of scientific research, usually in the form of physical anthropology and its widespread axioms.1

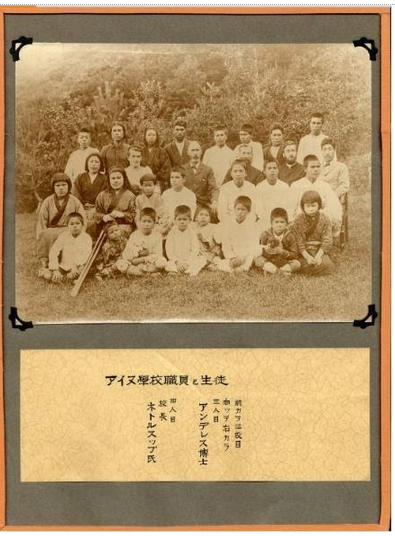

Figure 2: Shiina Sukemasa, Yachigashira (Hakodate) Ainu School with Charles Nettle (seated, centre third row) and his wife (seated, third row, second from left), Rev. Walter Andrews (seated, third row, third from right), and Rev. George Cecil Niven (seated, third row, second from right), 1897. 9.5 X 13.5 cm. @ Hakodate Central Library.

Figure 3: Soldiers of the Japanese expedition under Commander-in-chief Saigō Jūdō (西郷 従道 1843-1902), pictured with leaders of Seqalu (Native tribe of Taiwan), 1874 @ Yasukuni Shrine archives.

Japan’s process of modernization was accompanied by the adoption of these ideologies and practices, driving Japan’s leaders to establish their nation-state, the imagined community of “Japan,” and to follow the racial discourse dominating the political sphere, with a small twist: although Japan had been grouped with other Asian nations in the prevailing discourses of race, it nevertheless strove to associate itself with the white, European/Western race. Leaders and ideologists, for example, assigned inferior racial attributes to the different groups and ethnicities on or around the Japanese islands, gradually pulling Japan away from Asia, and closer to Europe. The Meiji era (1868–1912), therefore, saw Japan’s passage into modernity and identification as a modern state first within its own boundaries, and then, in terms of broader affiliations and international relations, Japan’s efforts to associate itself with Euro-American processes, developments and racial discourses, simultaneously distancing itself from Asia in general, China (and Korea), in particular.2

Figure 4: General Kuroki Tamemoto (黒木 為楨1844-1923) and his army, on the balconies of the Changdeokgung Palace (昌德宮) in Seoul, 1905.

While it would be impossible to thoroughly examine the enormous changes that took place over the course of this period, the articles in this issue aim to highlight some cases and questions at the center of Japanese engagement with concepts of race and empire, as well as how these ideas came to shape ideology and political practices in the Meiji era. Each of the articles tackle these issues through explorations of Japan’s direct (at times, personal) exchanges with European leaders and ideologists, invited specialists, missions, journeys and individual encounters in Europe and the USA. Such exchanges had been designed as opportunities to learn, explore and adapt Western ideologies, technologies, practices, political and financial systems, industrial and scientific knowledge, with the end goal of situating Japan on a new stage of development paralleling that of Europe, where the Japanese “race” was equivalent to the “white race” of Europe.

Figure 5: The Iwakura Mission. Tomomi Iwakura (岩倉 具視 1825–1883), Head of the Mission, is seated at the centre, in traditional clothing, London, 1872.

Mark E. Caprio’s article discusses the question of making Japan equivalent to the “white race” in his analysis of the Iwakura Mission’s visit to the United States and Europe (1871-1873). One of the first, most involved encounters between Japanese officials and the West, the Mission left Japan just after the Meiji government had assumed administrative responsibilities in 1868, seeking information on institutions that could reorganize Japan’s geographical boundaries, as well as its governmental bodies and prefectural relations. Through its travels, the Mission also encountered nations embarking on a new phase of imperial expansion, which set off a debate among the Mission’s participants: while the majority returned with visions of Japan becoming an empire, others saw their country’s future as a small, neutral state, following the example of Swiss diplomatic neutrality. The debate over these visions carried over into the Taishō period as Japan incorporated territories at its peripheries, including Ezo (Hokkaidō) the Ryūkyū islands (Okinawa), Taiwan, Sakhalin (Karafuto) and Korea. With these developments in mind, Caprio’s article examines the impact of the Mission participants’ views, which were informed by their first- and second-hand experiences of American and European amalgamation of peoples of diverse cultural, ethnic, and racial origins. Such experiences shaped the participants’ views of Japan’s future as an expansionist state, and taught them about the possibilities of turning assimilation into a centralized Japanese discourse.

Tarik Merida’s article adds another layer to the discussion on Japan’s engagement with racial beliefs and practices in the West, analyzing the time when Japan, already advanced and modernized, was seen as a racial other from the American perspective, even as Japan’s international relations had become interracial and complex in its identification with Asia. Since the age of exploration, “scientific” and geopolitical development had become mutually reinforcing concepts, propping up the idea of a superior “white race” meant to rule over various “nonwhites.” The problem was fitting Japan into this set of relations, a task that was becoming increasingly difficult. Officially “yellow” on paper, the Japanese people had, by the end of the nineteenth century, reached the “standard of civilization” – that is, the prerequisites that marked a modern nation, and that were seen as default and exclusive identifiers of the “white race.” Japan reaching the “standard of civilization” therefore generated the anomaly of a “colored race” exhibiting qualities otherwise understood as beyond their capacity. In response, United States President Theodore Roosevelt (1858–1919) devised a space of negotiation, where Japanese people were granted privileged racial status, allowing them to temporarily circumvent the prejudices that beset other “colored races,” particularly the Chinese and Korean immigrants in California – the very same communities from which Japanese immigrants wanted to dissociate themselves.3

When Japan embarked on the process of modernization – bolstered by the nationalism and racism that were, in turn, shaped by 19th Century scientific research – it was led by concepts of classification and categorization. As a result, racial discourses gradually became mainstream knowledge and attitude, with Japan struggling with its own position between Asia and Europe.4 One strategy that helped position Japan closer to Europe and “white (race) supremacy” was the act of identifying nations and ethnic groups that were “lesser,” or “inferior” to Japan, and in doing so, marking Japan’s practices and policies as superior and more European.

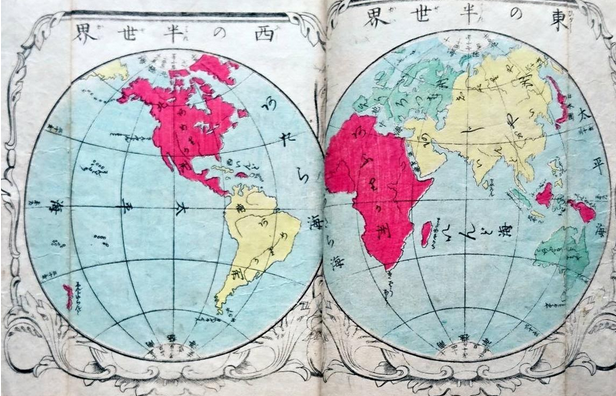

Figure 6: Fukuzawa Yukichi’s (福澤諭吉 1835-1901) Sekai Kunizukushi (世界国尽) Originally published in 1869.

In Elena Baibikow’s article, we learn how the education system worked towards this goal, and how values of the newly modern, Europe-oriented Japan were taught to children. Baibikov’s research looks into Fukuzawa Yukichi’s (福澤諭吉 1835-1901) educational geography textbook, which was written for children. Originally published in 1869, it was recently upgraded and republished in 2017. It is clear that this book played an important role in determining early Meiji concepts of geography and the subsequent organization of the world’s population. In the field of textbook research, argues Baibikov, it has been long established that schoolbooks are culturally determined, functioning not only as pedagogical apparatus, but also as cultural texts that expose deeper trends and educators’ visions for the next generation. Recent socio-historical scholarship of early Meiji textbooks provides insights into the formation of social consciousness and the transformation of Japan’s position vis-à-vis its geopolitical Others at the time, developments that came about inter alia through hierarchy-based discussions of race and civilization. Fukuzawa’s elementary geography book Sekai kunizukushi (All the Countries of the World) was one of the most influential Meiji textbooks. Some 150 years after Sekai kunizukushi‘s initial publication, a more recent edition was published under the title Learning about the World through Fukuzawa Yukichi’s Sekai kunizukushi, which was accompanied by commentary, gendaigoyaku (translation into modern language) and other extra-textual features. Baibikov takes a constructionist approach to the hierarchy of images depicting race and civilization, as introduced in the original textbook, and compares them to their “recycled” versions.

The discourses of race and empire were central to the making of the modern Japanese state and modern Japanese identity, having significantly shaped the core ideologies behind Japan’s expansion policies, which were first enacted in the neighboring territories annexed to Japan. By the late Edo period, Japan had already annexed Hokkaidō, as well as the Kuril Islands just north of the island, specifically through treaties Japan had negotiated with Russia. Subsequently, the Ryūkyū Kingdom was gradually occupied, until its formal annexation in 1879, which indicated the kingdom’s successful colonization. Afterwards, Japan gradually moved into other territories (Taiwan, Southern Sakhalin and Korea), before embarking on a full-scale war in north-east and south-east Asia, driven by an imperial and colonial desire.5

Yet, as has been commonly understood in recent decades, it was largely ideology, imagination, repressed desires, and greed at work in this process.6 Far from the image of “scientific truth” or “proven knowledge,” Japan’s expansionist practices, as well as its efforts to align itself with Europe marked ideological, practical steps towards “leaving Asia.”7 At the same time, the likelihood of obtaining the same status as Europe seemed slim, as European nations, along with the United States, showed clear signs that they would not accept Japan as one of the elite, leading powers, nor did they do so even decades later.8 Japan was ultimately accepted to the League of Nations, but then experienced a second round of what the Japanese administration saw as “unequal” treaties. The tensions between the desire to leave Asia behind and the uncertain prospect of equality with Europe underlie many of Japan’s decisions during those years.9

Japan’s two-pronged path into modernity therefore involved, on one hand, self-definition as “Japan” the nation-state against outside countries (外国gaikoku).10 The task of differentiating Japanese culture entailed the demarcation of Japan’s histories from those of Asia, detailing Japan’s cultural specificity,11 while essentializing “Asia” as its Other. On the other hand, the desire to adopt European values and norms, to align Japan with European cultures engendered Japan’s impulse for comparison, as evidenced by the constant comparisons between Japanese life and achievements, and their counterparts in various European countries. In the process of observing, expanding, and retaining which strategies would be useful for Japan’s modernization process, the Japanese administration came to understand a great variety of cultures and conduct simply as strong or weak. The double movement of association with Europe and distancing from Asia produced a new subtext to the binary opposition between the “advanced” and “sophisticated” versus the “primitive” and “simple-minded.” That is, the logic behind Western colonialism was re-applied to relations between Asian nations and cultures, without the explicit binaries of East and West. Ultimately, this double movement laid the foundations for racial ideologies and imperial practices.12

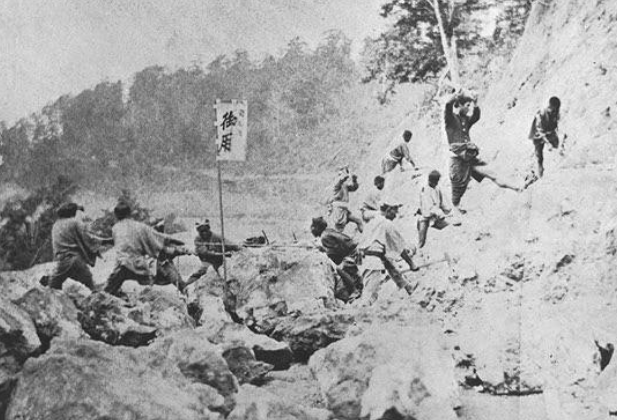

Figure 7: Tamoto Kenzō, Demolishing hard rocks for mountain road no. 737 in Musawa, Meiji 5 (1872) Albumen print 14.5X20cm. @ Northern Studies Collection, Hokkaidō University.

On one hand, Japan aspired to Western civilization standards as it harbored a sense of “inferiority” (especially in terms of technological and scientific accomplishments), and on the other, Japanese leaders adopted the Western stance of “superiority” over the rest of Asia, deeming the latter’s various cultures and peoples “inferior.”13 This perspective translated into action in Japan’s encounters with the neighboring islands of Hokkaidō and Ryūkyū, as discussed in Pia Jolliffe and Stanislaw Meyer’s pieces, as well as with Taiwan, and later, even farther Asian nations, such as Korea, Manchuria, and Mongolia, with which Japan had had long-standing cultural relations. In the process of adapting Western cultural discourses, Japanese government bodies worked to align Japan’s development with the enlightenment and progress it associated with Europe and white civilizations.14 At the same time, Japan sought to distinguish itself from Asia, especially China, a major source of influence that had significantly shaped Japanese culture over the course of the previous millennium.

Closer to home, the ideological and political leaders of Meiji Japan saw the Ainu of Ezo (Hokkaidō) in the north, and the local cultures of the Ryūkyū Kingdom in the south, as “primitive” and “underdeveloped.”15 Ezo was already known to such leaders in the Edo period, thanks to Matsuura Takeshirō (松浦武四郎1818–1888), who had traversed Ezo and Sakhalin on foot between 1846 and 1858, reaching as far as Etorofu (択捉島, Ru: Iturup) in the Kuril Islands. Matsuura recorded the names of places and Ainu sites on Ezo, publishing them in a series called, “Survey Map of the Mountains, Rivers and Geography of East and West Ezo” (1859).16 In the Ryūkyū Kingdom, Japanese rule and involvement began as early as 1607, with the Satsuma clan the first to invade and rule over the islands.17

Unlike Matsuura’s ostensibly objective land survey and research into Ezo, the early Meiji era was marked by a drastically different attitude, one that racialized Japan’s neighbors, and sought to conquer the lands of “incapable” ethnic groups. At one extreme, Meiji administrators even sought to exterminate such groups, as was the case of the Ainu in Ezo. Elsewhere, they tried to re-educate these groups on the aspects and values of Japanese culture, which was the case in Ryūkyū (now Okinawa, the name of the archipelago’s main island), as well as in Taiwan, Karafuto (South Sakhalin), and Korea. In implementing such strategies, Japan was able to subsequently identify itself as “superior” and “enlightened,” in contrast to such groups newly identified as “primitive” and “incapable.” This process was especially evident in Hokkaidō, where the land was perceived as a “blank slate” awaiting re-interpretation and the progressive movement of modern Japan.18

The problems that arose from the annexation of Hokkaidō and the Ryūkyūs were numerous, and challenged Japanese authorities’ abilities to cope with Japan’s expanding territories, as well as with the ethnic groups that had heretofore not been considered Japanese. The authorities therefore had to debate the best way to incorporate these new territories and their assets, such as raw materials and land for cultivation, into the Japanese system. Pia Jolliffe’s article examines the role of forced labour in the context of Ezo/Hokkaidō’s colonization, drawing attention to how different groups of subaltern people – the indigenous Ainu, political convicts, indentured labourers and Korean workers – contributed to the making of imperial Japan’s first colony and the building of the modern Japanese nation state. Yet, though they worked for the same Japanese ruling class, these subaltern labourers were not united. Jolliffe highlights how their experiences were largely shaped along ethnic, gendered and generational lines.

Figure 8: King Shō Tai (尚泰 1843-1901), the last king of the independent Ryūkyū Kingdom.

Stanislaw Meyer’s article turns to the other end of the archipelago, and introduces the Meiji government’s policy on Okinawa, which has sparked heated debate among Japanese and Okinawan scholars. The controversies particularly concerned the early years of Japanese rule in Okinawa, following the Ryūkyū Kingdom’s annexation in 1879, when the Japanese government, having met with opposition from Ryūkyūan aristocracy, decided to postpone structural reforms in the prefecture for the sake of political stability. As a result, Okinawa remained the poorest and most forgotten region in Japan until the early 20th Century, frozen in the structures of feudalism. The growing gap between Okinawa and mainland Japan contributed to the emergence of negative stereotypes of and social discrimination against Ryūkyū people in Japanese society. Once the government initiated Okinawa’s integration into mainland Japan, Okinawan society was subjected to a policy of assimilation, engendering an identity crisis among many people on the islands. Seeing that Okinawa was unable to overcome the stereotype of a backward, peripheral prefecture, even the most fervent pro-Japan advocates, such as journalist Ōta Chōfu (1865–1938), acknowledged that Japan treated Okinawa like a colony. Yet, in many respects, Okinawans’ experiences of Japanese rule differ from those of the Ainu, Taiwanese and Koreans. In order to understand Japan’s policy on Okinawa, Meyer considers the following factors: Okinawa (along with Hokkaidō, the Kuril Islands and Ogasawara Islands) was incorporated during the early stages of the Japanese modern nation state’s formation. At the time, there was no clear concept of a “Japanese nation,” and it was only after the Sino-Japanese War that Japan drew a clear line of distinction between “Japan proper” and its colonies, between Japanese people and Japanese subjects. Unlike Hokkaidō, Okinawa had no natural resources and was of little value to the Japanese economy. As a result, Okinawa escaped physical colonization and mass migration from mainland Japan to Okinawa. These developments, argues Meyer, are the clues to understanding why Okinawa was nearly absent in Japanese colonial discourse, as well as why the Okinawan people were not demonized as barbarians. Had Okinawa been a rich land, Japan would most likely have coined an ideology justifying its appropriation, especially on the grounds of Japanese people’s racial superiority, as was the case in Hokkaidō. Unlike other colonial subjects, race was not a factor determining Okinawans’ status in Japanese society, although Japanese people’s attitudes towards them often bordered on racism. Crucially, there was no institutional discrimination against Okinawan people based on racial or ethnic criteria. At the same time, there was relatively little resistance in Okinawa against Japanese rule: from the 1890s, Okinawans took initiative in promoting Japanese culture and patriotism. Not only had Okinawans adopted a Japanese identity, but they also strove to establish links between the Japanese and Okinawan peoples. Seeing Okinawans’ zeal in becoming Japanese, Japan gradually changed its approach to and administrative practices for Okinawa.

In contrast, the Meiji administration’s approach to modernizing and making Hokkaidō more Japanese served as the blueprint for its colonial campaigns overseas, in Taiwan, Korea, Karafuto, and Manchuria. Mid-nineteenth century racial discourses served as the ideology behind the occupation of these nations, as well as the justification for Japan’s dissemination of ideology via the establishment of state Shintō, the construction of shrines throughout the colonies, and the promotion of Japanese language as the means of acculturating “native” populations.19 Officers and scholars who had trained and worked in Hokkaidō were recruited to carry out Japan’s policies throughout the empire, where they subsequently drew on their previous experiences.20 Race and empire were thus entangled concepts behind both theory and practice, enabling and serving to justify Japan’s process of becoming the biggest imperial super power in East Asia.

The articles in this special issue discuss different aspects of building the Japanese empire through racialization, taking comparative approaches to Europe and Asia, and Japan’s repeated efforts to associate itself with the West by adopting various European and American cultural values. This special issue further expands on the concepts of race and empire in the political, economic and administrative discourses and practices in newly annexed territories (Hokkaidō and Okinawa), as well as in the ways school textbooks conveyed such concepts to the new generation of the Meiji era. The much later adaptation, translation and re-publication of such textbooks indicate how their concepts persist to some degree even in contemporary Japan. The case studies presented here highlight how Japan wrestled with its own position and political orientations, struggling with “scientific” and ideological frameworks, as well as with debates about its imperial frontiers. Ultimately, Japan’s move to associate itself with the “white race,” to position itself among the leading nations of Europe, exacted a heavy price on the complex relationships between multiple ethnicities and identities in the Japanese archipelago itself, as well as in the lands traversed during Japan’s imperial expansion across Asia. It is particularly the latter where inequality and racism took root, yet to be fully addressed or reconciled in the present day.

Bibliography

Books

Paul D. Barclay, Outcasts of Empire: Japan’s Rule on Taiwan’s “Savage Border,” 1874–1945 (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2017).

Elazar Barkan, The Retreat of Scientific Racism: Changing Concepts of Race in Britain and the United States between the World Wars (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1992).

Hilary Conroy and Wayne Patterson, ed. Japan in Transition: Thought and Action in the Meiji Era, 1868-1912 (London: Fairleigh Dickson University Press, 1984).

Carol Gluck, Japan’s Modern Myths: Ideology in the Late Meiji Period (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1985).

Marius Jansen, The Making of Modern Japan (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002).

Michele Mason, Dominant Narratives of Colonial Hokkaido and Imperial Japan Envisioning the Periphery and the Modern Nation-State (London & New York: Palgrave-MacMillan, 2012).

Matsuura Takeshirō (松浦武四郎). Ezo nisshi (蝦夷日誌) (Tokyo: Jiji Tsūshinsha, 1962); Takakura Shinichirō (高倉新一郎), Takeshirō kaiho nikki (武四郎廻浦日記)(Sapporo: Hokkaidō Shuppan Kikaku Sentā, 1978);

__________________________. Matsuura Takeshirō zenshū (松浦武四郎選集) [Complete works of Matsuura Takeshirō] (Sapporo: Hokkaidō Shuppan Kikaku Sentā, 1996–2008).

Michael S. Neiberg, The Treaty of Versailles: A Concise History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017).

Okakura Kakuzō (岡倉覚三), The Book of Tea (茶の本) [Cha no Hon] (New York: Duffield & Company, 1906).

_____________, The Ideals of the East with Special Reference to the Art of Japan (London: John Murray, 1920).

Stefan Tanaka, Japan’s Orient: Rendering Pasts into History (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1993).

Robert Thomas Tierney, Tropics of Savagery: The Culture of Japanese Empire in Comparative Frame (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2010).

Michael Weiner, ed., Japan’s Minorities: The Illusion of Homogeneity (London: Routledge, 1997); Barbara Poisson Aoki, The Ainu of Japan (Minneapolis, MI: Lerner Publications, 2002).

Henk L. Wesseling, European colonial empires 1815-1919 (London and New York: Routledge, 2016).

____________, Imperialism and Colonialism: Essays on the History of European Expansion (Westport, CT and London : Greenwood, 1997).

Yoshida Takejō (吉田武三), Zōho Matsuura Takeshirō (増補松浦武四郎) (Tokyo: Matsuura Takeshirō Den Kankōkai, 1966).

______________. Sankō Ezo nisshi (三航蝦夷日誌) (Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kōbunkan, 1970).

Articles

Michael Adas, “Imperialism and Colonialism in Comparative Perspective,” The International History Review, Vol. 20, No. 2 (1998): 371-388.

Robert Eskildsen, “Of Civilization and Savages: The Mimetic Imperialism of Japan’s 1874 Expedition to Taiwan,” American Historical Review vol. 107, no. 2 (2002): 388–418.

Fukuzawa Yukichi (福澤諭吉) Bunmeiron no Gairyaku (文明論之概略) [An Outline of a Theory of Civilization] (1875),

_______________. “Datsu-A ron,” Fukuzawa Yukichi zenshū, dai 10 kan (Tokyo: Iwanami shoten, 1970 [1885] ):238-240.

Karatani Kōjin, “Japan as Art Museum: Okakura Tenshin and Fenollosa,” in A History of Modern Japanese Aesthetics, ed. and trans. Michael Marra, 43–52 (Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai’i Press, 2001).

Nakajima Michio, “Shinto Deities That Crossed the Sea: Japan’s ‘Overseas Shrines,’ 1868 to 1945,” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies vol. 37, no. 1 (2010): 21–46.

Pekka Korhonen, “Leaving Asia? The Meaning of Datsu-A and Japan’s Modern History,” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, Vol. 11, Issue 50, No. 1, March 3, 2014. Article 4083

Morris Law, “Physical Anthropology in Japan the Ainu and the Search for the Origins of the Japanese,” Current Anthropology Vol.53, Supplement 5 (April 2012): S57-S68.

Tessa Morris-Suzuki, “Race,” in: Re-inventing Japan: Time, Space, Nation (New York: Sharpe, 1998).

Sakamoto Rumi, “Japan, Hybridity and the Creation of Colonialist Discourse,” Theory, Culture & Society vol. 13, no. 3 (August 1996): 113–28.

Suga Kōji, “A Concept of ‘Overseas Shinto Shrines’: A Pantheistic Attempt by Ogasawara Shōzō and Its Limitations,” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies vol. 37, no.1 (2010): 47–74.

Uemura Hideaki, “The colonial annexation of Okinawa and the logic on international law: the formation of an ‘indigenous people’ in East Asia” Japanese Studies vol. 23, no. 2 (Winter 2003): 213–222.

Uehara Kezen (上原兼善). “Shimazu Clan Raid of the Ryūkyū: Another Invasion (of Korea 1597-8)” (「島津氏の琉球侵略 : もう一つの慶長の役」) Ryūkyū Arc Series No. 19 (April 2009)『琉球弧叢書;19))』2009年4月。

Notes

Much had been written on the abolition of Race Science or Physical Anthropology in recent years. See, for example: Barkan (1992) and Law (2012).

The term for outside countries was borrowed from Chinese and used primarily during the Meiji period to refer to non-Asian/European cultures, which, in the Japanese imagination, served as perfect models for the remaking of its own image. Sakamoto (1996).

Okakura Kakuzō 岡倉覚三 notably attempted to identify Japan within the Asian sphere, as an opposition to the “Occident,” by using a terminology of “East” and “West.” See: Okakura (1906) and Okakura (1920). A critique of Okakura’s approach is found in Karatani (2001). For a further critique of Japan’s relation to Asia in general and China in particular, see Tanaka (1993).

See for example, Fukzawa [1875] which was influenced by François Guizot’s Histoire de la civilisation en Europe (1828; Eng. trans in 1846) and Henry Thomas Buckle’s History of Civilization in England (1872).