Abstract: Shortly after the Meiji government assumed administrative responsibilities in 1868, the Iwakura Mission left Japan to circumvent the globe, searching for information on institutions that could centralize a divided archipelago. In so doing, it encountered a world embarking on a new phase of imperial expansion. While the majority of the Mission’s participants returned with visions of a large, expansion-oriented Japan, others saw their country’s future as a small, neutral state. Debates over the suitability of either vision continued throughout the Taisho period, especially as Japan incorporated territories at its peripheries, including Ezo (Hokkaidō), the Ryūkyū Islands (Okinawa), Taiwan, and Korea. This paper examines the impact of the Mission participants’ perspectives, which were informed by their first- and second-hand experience of American and European amalgamation of peoples of diverse cultural, ethnic, and racial origins. How did the participants’ experiences influence their views on Japan’s future as an expansionist state? What did their experiences teach them about the assimilation of peoples of diverse backgrounds? This paper identifies the legacy of these debates as extending to the present, where Japan seeks to rescind postwar restrictions against extending military powers beyond its borders.

Keywords: Foreign Policy, Large/Small country, Iwakura Mission, Neutrality, Invade Korea debate, Miura Tetsutarō

Within a body under autonomous rule (jishū dokusai), it is not debated whether a country is big or small, strong or weak. Its independent, absolute rule is based on whether there are places in the empire where the king’s orders do not reach. Though the country might be large, if the orders do not extend throughout (his realm), if political orders are different in every place, if the orders given are different from the king’s orders, the country suffers from divided sovereignty (han shukoku). Even a big country like China has not fallen to such a state; on the other hand, it is possible for a small country like Holland to lose its autonomy.1

Figure 1: Iwakura Tomomi

The above passage, delivered by Prince Iwakura Tomomi (1825—1883), who led a Meiji-era tour of 103 Japanese government officials, scholars, and students on a fact-finding mission that circumvented the globe, reflects a formidable challenge that the nascent administration confronted: reconfiguring a collection of pseudo-independent Edo-era domains (han) into a centralized nation. Iwakura’s statement clearly delineates the Mission’s goal as investigating ways to ensure that the emperor’s voice was heard, recognized, and obeyed by the people residing within “Japan”: then Honshū, Kyushū, and Shikoku, as well as the newly annexed island of Ezo (just recently renamed Hokkaidō). A future consideration was whether this voice would extend to peoples of other annexed territories, and if so, the extent to which they would be subjected to the “king’s orders.”

The new Meiji government commenced its administrative duties in the recently renamed city of Tokyo (formerly Edo), and on December 23, 1871, the Mission departed from Yokohama, leaving behind a skeleton government that was instructed to handle routine matters but warned not to initiate new policies. The participants’ course was truly ambitious for any time period, much more so for the late nineteenth century: They sailed across the Pacific Ocean to the United States; traveled by train from the west to the east coast, where they toured Washington, D.C., Boston, and New York City; crossed the Atlantic Ocean to tour fourteen European countries; and along their return route, made brief stops at Ceylon (presently Sri Lanka), Hong Kong, and Shanghai to complete their trip around the world. En route they toured the citadels of civilization in the western world, inspecting institutions of education, military, industry, politics, and punishment. They held court with the architects and minders of these institutions in search of information useful for molding their own institutions in the new Japanese state. Additionally, the Mission delivered Japanese students, including six young girls, to educational institutions along the way.

The timing of the tour, and its potential influence on Meiji-era Japanese expansion, cannot go ignored. Along the Mission’s route were vivid signs that the world powers were set on initiating another wave of national expansion, through extending a hegemonic culture both within and beyond what these states recognized as their sovereign territory. This wave, in part, was encouraged by developments in the wake of two recent wars on either side of the Atlantic Ocean: The Reconstruction Era that followed the United States Civil War (1861—1865), and the wave of overseas colonialism precipitated by the Franco-Prussian War (1870—1871). The tour encountered efforts by states to expand and centralize their constituencies. (Prussian ambitions to consolidate a German nation closely resembled those harbored by Meiji Japan). However, with few exceptions, the tour concentrated its travels on the global powers, and avoided territories they had, or soon would annex. The occasional mentions of Japan’s future expansion in the tour’s True Account2 suggests that this expansion was a topic of discussions between tour members and the people they encountered along their long journey. Tour members were also most likely exposed to counter-arguments in states not engaged in this expansion, but which championed neutral (small state) diplomacy that avoided matters of territorial expansion beyond their borders.

Within a matter of decades, Japanese efforts succeeded in creating a state where the voice of the center—the emperor—carried to all corners of the realm. In this regard, the domestic goals set by the tour were met with remarkable success. However, from evenbefore the Mission’s departure, Japan had also begun to develop as a “large” state, one that extended its influence into territories in its immediate peripheral areas, and threatened others that extended beyond these annexed territories. Though the Mission was introduced to the trials and tribulations of both large and small states, in the end, Japan opted to continue to develop as a large, expanding state—a Prussian model instead of a Swiss one—in its quest to develop a “rich country [protected by a] strong military” (fukoku kyōhei). Drawing on the True Account, this article considers how the Mission observed and responded to both options. To what extent did their travel experiences influence the Mission participants’ views on the choices open to Japanese over the direction of their country’s diplomatic future?

Edo-era Influenced Colonial Expansion and National Security Rhetoric

It has been argued that Japan’s imperial history commenced with its victory in the Sino-Japanese War (1894—1895), when the peace treaty ceded Taiwan and the Pescadores Islands to Japan.3 However, the argument that a state’s national security required it to incorporate peripheral buffer territories can be found as early as the late eighteenth century, as a counter to intrusions by Russian explorers, who crossed Siberia to explore Ezo and the neighboring Kurile Islands. In response, the Tokugawa bakufu assumed control over the island and attempted to assimilate its indigenous Ainu inhabitants as Japanese.4 The administration soon abandoned this plan, but the potential threat that certain Japanese scholars saw in this Russian advance encouraged some to use the intrusion as the basis for the island’s annexation and fortification, specifically as a means of protecting the archipelago. In his 1798 book, A Secret Plan of Government (Keisei hisaku), Honda Toshiaki (1744—1821) described how Russians explorers fit a common pattern of imperial expansion: The colonizers first “inspire an affection and obedience [among the natives], like the love of children for their parents,” in preparation for assuming total control over the targeted area. In defense, Honda advised, Japan must absorb Ezo and situate one of its three national capitals (the other two being Osaka and Edo) on the island.5

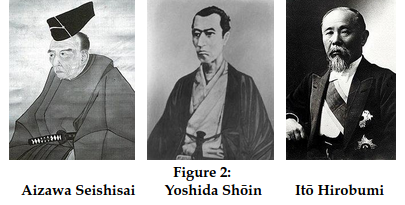

The Mita domain scholar Aizawa Seishisai (1782—1863) joined a growing number of Japanese, who, influenced by the writings of Honda and others, issued strong warnings about the dangers that encroaching foreign powers posed for Japanese security. In his 1825 New Thesis (Shinron), Aizawa warned that encroaching powers would use the less advanced northern islands as a bridge to invade Honshū. He laid out a two-part plan to strengthen Japanese defense lines: it would first consolidate and then “tak[e] the offensive.” By this latter objective, he meant expansion: “We should annex the Ezo Islands and absorb the barbarian tribes on the continent; we should roll back the tide of barbarism and extend our frontiers ever forward.”6

Aizawa’s thinking in turn inspired the Chōshū intellect, Yoshida Shōin (1830—1859), who visited the aged scholar six times while traveling through the Mita domain. Yoshida’s vision of an expanded Japan also targeted Russia as Japan’s most immediate concern, but he eclipsed his mentor’s plan by extending Japanese influence over to the Asian continent. In 1855, he made the following ambitious proposal:

As we have already established amicable relations with Russia and America, no untoward event whatever must occur on our side. Carefully respecting the regulations and with attention to our promise, we must give them no cause for arrogance. Taking advantage of favorable opportunities, we will seize Manchuria, thus coming face to face with Russia; regaining Korea, we will keep a watch on China; taking the islands of the South, we will advance on India. Planning on all three, we must determine which is the easiest, and put that into effect first. This is an enterprise which must continue eternally so long as the earth shall exist.7

Yoshida was executed at the tender age of 29 by the Tokugawa regime for his participation in a plot to assassinate a government representative. However, the successful, post-Meiji Restoration careers of a number of his students, the most prominent being Itō Hirobumi (1841—1909), carried many of Yoshida’s ideas into a Meiji era that ended with Japan controlling a number of territories in its immediate vicinity. As many as four of Yoshida’s students, including Vice-Ambassador Itō, traveled with the Iwakura mission.8 One influential figure who was not included on the tour, Yamagata Aritomo (1838—1922), had been influenced by European military practices during an 1869 trip to Prussia and France the year before the two states were to meet on the battlefield.9

By the time of the Mission’s departure, the Japanese state had already accomplished the primary goal proposed by Honda, Aizawa, and Yoshida, as late Edo-era officials had negotiated with Russia for Japan’s possession of Ezo and neighboring islands. The nascent Meiji government quickly resumed the aborted program initiated by the Tokugawa regime to assimilate the region’s indigenous peoples. In addition, the government also embarked on the more difficult enterprise of securing the Ryūkyū Kingdom. Gaining control over this territory meant competing with China, which had also long exercised suzerainty over the islands. A third diplomatic effort involved “modernizing” Japan’s diplomatic relations with another peripheral territory, the Kingdom of Korea. Rather than annexing the peninsula, at this early stage, Japan’s efforts centered on simply altering the “unequal,” Edo-era arrangement that forced Japan to rely on officials from the island of Tsushima to conduct business with Korea. The Koreans restricted these representatives to the Pusan wagwan (house of Japan); they did not allow them to advance to Seoul, the capital. Korean envoys, on the other hand, were able to travel to Edo, which they did on twelve occasions, primarily to acknowledge the enthronement of a new Shogun. The Korean government refused to entertain Meiji Japan’s demands to negotiate the two countries’ diplomatic relations. Their refusal perpetuated a vicious debate in Japan, the Seikanron (invade Korea debate), over how Japan should respond to this Korean “insult” of not accepting Japanese envoys.

The Mission’s departure coincided with a moment in history when a number of governments across the United States and Europe initiated major policy changes that transformed both their domestic and diplomatic fabrics. Much of this change resulted from the Western powers’ direct and indirect involvement in the above-mentioned wars in the United States and Europe. These wars encouraged a new wave of expansion that included efforts to centralize peoples within their borders through hegemonic political and cultural forces (internal expansion), to annex neighboring territories and peoples (peripheral expansion), and to incorporate territories and peoples in geographically distant lands (external expansion). These efforts required different levels of colonial administration: those peoples subjected to internal expansion were to be incorporated as national subjects or citizens; those residing in peripheral lands as imperial subjects administered by a gradual assimilation policy; and those residing in distant territories simply treated as human resources to be exploited for their labor, but not assimilated to any degree beyond what was necessary for securing their cooperation.10

Iwakura Mission Lessons on Expansion

The Mission’s timing provided the participants with a ringside seat to both observe this expansion and engage its agents in discussion. The Mission’s True Account classified peoples according to their level of civilization, which, in turn, was based partially on their levels of production and education, as well as the degree in which they enjoyed national sovereignty.

Figure 3: Leaders of the Mission Surrounding Iwakura Tomomi.

Figure 4: Five of the six female participants on the Mission.

The three categories, “civilized” (bunmei), semi-open” (hankai), and “barbarian” (yaban) roughly coincided with the internal, peripheral, and external levels of expansion. The Japanese delegation, perhaps identifying themselves as members of this middle group, embarked on the tour to gain from “civilized” peoples the knowledge that would allow them to advance to this highest group. Just as important was their hosts’ recognition of them as a people capable of making this advancement. They were not, as their hosts generally categorized Asians, “barbarian.” The Mission’s ambition is reflected in the five-volume account of the tour, as compiled by the historian Kume Kunitake. In Washington, D.C., Kume recorded the advances that “colored” peoples had made since being liberated from slavery. At this time, he noted insightfully that, although the people’s “ugliness is extreme,” their skin color

has nothing to do with intelligence. People with insight have recognized that education is the key to improvement, and they have poured their energies into the establishment of schools. It is not far-fetched to believe that, in a decade or two, talented black people will rise and white people who do not study and work hard will fall by the wayside.11

The Japanese delegation, too, learned that although they were behind as a people, they could catch up if they poured their energies into education and similar institutions.12

Such rhetoric, no doubt influenced by post-Civil War Period of Reconstruction efforts, suggests that the Japanese delegation considered the possibility that former slaves might one day assume a social rank equal to that of white America, if the government were to create and fund institutions appropriate for increasing their social capital. Given that the schools they observed were no doubt segregated and inferior in terms of facilities, Kume’s lofty predictions would likely have been difficult to manifest. Had the Mission had the chance to observe the trying conditions of the Black schools in the American South, it most likely would have had to adjust its rather optimistic predictions of Black America’s future.13

At the time of the Mission, America’s Black (and Native American) population had less than peripheral status in the United States. A defining characteristic of a “large country,” the Mission concluded, was the government extending its influence over these peoples to incorporate them as imperial (semi-open), rather than national (civilized) subjects. Throughout late Edo, a number of Japanese scholars expressed concern that their country’s most immediate threat, Russia, aimed to subjugate them as peripheral subjects. In this sense, their observations of less developed peoples generated an understanding of characteristics they needed to avoid in order to increase their likelihood of being recognized by the world powers as a civilized people. In Scotland, the Mission saw an example of a people divided between this middle and upper grouping. Whereas the True Account’s assessment of the Scottish generally glossed over their ethnic differences with the English, which had by the early eighteenth-century negotiated “unions” with Scotland along with Wales, and Ireland to form the United Kingdom, the Mission’s travels through the Scottish Highlands exposed its members to a people they saw as holding a peripheral or marginalized status. The language they spoke, in particular, proved to be difficult to understand, and their customs and mannerisms seemed rather primitive to the travelers.

Most of the people who live in the Highlands are of the Celtic race and speak the Gaelic language… There are over three million people of this race in Scotland. Their customs are simple and unrefined, and their dress picturesquely antique. Scottish soldiers wear Highland dress as their uniform.14

The travelers interpreted these differences as examples of “the ancient customs of a people being preserved unchanged in poor villages in remote mountain districts” to stifle development.15 As Japan prepared to annex Korea in the first decade of the twentieth century, commentators often compared these unions as examples of the arrangements they hoped to secure with the Korean peninsula. The Japanese delegation found England’s seemingly tranquil relations with Scotland a viable model for their own country, in sharp contrast to the more tumultuous relations England had with the Irish, then battling their subjugators for independence.16

At this early point in time, the True Account emphasized few connections between European expansion and Japan’s potential as an imperial power. This was despite the fact that Japan had already taken steps in this direction through its acquisition of Hokkaidō, and the ambitions it displayed toward annexing the Ryūkyū Kingdom. The French expansion into neighboring Algeria, however, produced one of the few mentions of Japan’s relations with another peripheral territory, Korea. At the conclusion of the Franco-Prussian War, France had replaced its military rule in Algeria with a civilian rule that emphasized an assimilation policy. Though the Mission did not visit Algeria, it is very likely that it engaged the French in discussions of this transformation, then in progress. The True Account applied this example in the Korean context to gesture at a possible imperial extension, observing that “Algeria faces France across the Mediterranean Sea in the same way that Japan and Korea face each other,” and that the people, as “followers of Islamic faith do not submit to French culture.”17 Decades later, Japanese colonial thinkers would raise the French-Algerian relationship as another example to guide its administration of Korea. At this time, with the assimilation experiment in Algeria still in its infancy, the Mission drew on a different dimension of the French-Algerian relationship: the colony’s economic value to France, particularly against the latter’s rival, the British empire.

The purpose of this [colonial] commerce is to enable private companies from their own country to exert a monopoly over the profits made from both cost and retail prices, enabling them to make huge gains by the time a product’s market value levels out, and guaranteeing continuing returns even at the lowest selling price. This is why Britain and France restrict trade from their colonies and prevent commodities from being exported to anywhere other than their own lands. Independent nations must always remain alert to these conditions and not squander any chance to take advantage of such opportunities as may arise.18

The True Account is silent as to whether the tour members deliberated with their hosts or amongst themselves over Japan’s future as a player in the large state diplomatic game of territorial monopoly procurement. Surely, however, they were aware that the lands on their periphery were quickly disappearing into the empires of one or another of the world powers. They probably realized the value of national expansion as a means of joining the large-country haves and escaping the ranks of small-country have-nots. Though not yet evident, the world powers’ efforts to monopolize their colonial markets would serve as a major cause for the two world wars in the next century. These consequences led to demands that the imperial nations voluntarily dismantle their colonial empires.19

Previous Japanese visits to the United States and Europe had introduced the value of display in instructing people in national development, as well as instilling in them a sense of place within racial hierarchies. The Mission, aware of this purpose and value, frequently added museum visits to their daily itineraries.20 The True Account included a lengthy discussion of their value after a visit to one of the world’s premier museums, the British Museum. Here, the visit impressed upon the Mission the museum’s capacity to record the state’s development across the ages. This observation offered the travelers guidance on the museum’s potential for tracing the development of their future state:

No country has ever sprung into its existence fully formed. The weaving of the pattern in the nation’s fabric is always done in a certain order. The knowledge acquired by those who precede them is passed on to those who succeed; the understanding achieved by earlier generations is handed down to later generations; and so we move forward by degrees. This is what is called “progress.”…. In the forming of a nation, therefore, customs and practices arise whose value is tested by constant use, so that when new knowledge arises, it naturally does so from [existing] sources, and it is from these services that it derives its value. Nothing is better than a museum for showing clearly the stages by which these processes happen.21

At the South Kensington Museum (presently the Victoria and Albert Museum), the Japanese delegation connected England’s prosperity with its industrial development and overseas expansion. England had gained an advantage over its European rivals early in the nineteenth century by avoiding the turmoil caused by the Napoleonic Wars, at which time England “began to acquire its overseas territories and to lay the foundations of its national prosperity” over a rather short four-decade timespan. The country’s efforts were aided by the invention of “steamship lines and railways in the 1830s [that] utterly transformed the trade of Europe.”22

The delegation’s experiences in England also introduced the travelers to a negative view of expansion. While visiting an arsenal in Woolwich, members of the Mission commented on the sheer quantity of weapons on display at the facility’s museum. They concluded that the display reflected the British people’s concern that their country “was beset by enemies on all sides.” Their host, General David Wood, offered a different perspective in suggesting that the “sole purpose of all these things is … the spilling of human blood. How can they be for the good of a civilized world?”23 Late nineteenth century England, with its vast colonial holdings, hardly represented a bastion of small-state diplomacy. But the True Record account of this experience reveals that even here, the Mission saw glimpses of the dark side of large-state thinking. Rather than elaborate on the pros and cons of this approach, however, the True Account simply continued its narrative by noting the lunch that the general hosted in their honor.

The Mission participants also gained insight into national character through display at the Vienna Universal Exhibition, which opened in May 1873. The third iteration of these exhibitions expanded on the previous two (which limited exhibitions to those from France, England, and their empires), and included exhibitions from 22 countries. Kume’s observations in the True Account echoed those of Iwakura quoted at the top of this paper: the products on display demonstrated the depth of the “spirit of independence in the people,” regardless of whether from a large or small state.

So far as each people’s earning an independent livelihood is concerned … the larger countries are not to be feared and the smaller ones are not to be despised. In both Britain and France, for example, civilisation flourishes and industry and commerce prosper together. However, when one looks at the products of Belgium and Switzerland [one is aware that] the achievements of their peoples in attaining independence and accumulating wealth would impress even the largest nation.24

A country could be large in geographic size, but small in diplomatic influence. One such country was Russia, the state that had struck fear among Japanese officials and scholars from the late eighteenth century. The Mission now saw Russia as a geographically large state that “cannot stand alongside the smaller nations.” Overwhelmed by the scale of the Exhibition, the True Account offered detailed evaluations of the displays assembled by the European states. It did not, however, have much to say on those prepared by colonized nations.25

Commentary from people that the Mission encountered during its tour provided yet another source of information, though these encounters received limited attention in the True Account. One exception was the tour’s meeting with Prussian Chancellor Otto von Bismarck. More than the established European powers, it would be Prussia that would wield the greatest influence on the Japanese travelers due to the similarities between the two countries’ respective situations, a point that the chancellor emphasized in the inspiring lecture he delivered before his guests.

Figure 5: Otto von Bismarck

Here, Bismarck highlighted the frustrations his country felt as a “small state” attempting to navigate international law. He lamented:

From the very beginning, the so-called international law, which was supposed to protect the rights of all nations, afforded [Prussia] no security at all. In cases involving a dispute, a great power would invoke international law and stand its ground if it stood to benefit, but if it stood to lose, it would simply change tack and use military force, so that it never limited itself to defense alone. Small nations like ours, however, would assiduously abide by the letter of the law and universal principles, not daring to transgress them so that, faced with ridicule and contempt from the greater powers, we invariably failed to protect our right of autonomy, no matter how we tried.26

Bismarck explained that his country “made great efforts to promote a patriotic spirit with a view to becoming a country which merited due respect in diplomatic affairs.”27 Finally, he proposed that due to his state’s “the respect in which we hold the right of self-government,” it would be wise for Japan to prioritize friendly relations with Prussia over other states, with which Japan might, at the moment, be enjoying “amicable diplomatic relations.”28

The Japanese delegation in attendance no doubt identified with the chancellor’s bitterness: had they not experienced similar frustrations in their attempts to renegotiate the “unequal” treaties that the Western powers forced upon them from the 1850s?29 Contemporary Prussian efforts to unify the Germanic states and expand its influence into peripheral territories – such as Austria, along with the Alsace and Lorraine territories it had acquired from France as war trophies – also resonated with the Mission’s goal of developing and strengthening institutions for reorganizing the former Edo-era domains, and incorporating the annexed northern Hokkaidō territory and the soon-to-be acquired Ryūkyū Kingdom. Like the cases of Algeria and Scotland, Prussia’s recent acquisitions would later serve as examples of how Japan might administer the Korean peninsula.

Whereas in Prussia the Mission witnessed a self-defined “small state” with large state ambitions, in Switzerland the Mission encountered a state that prided itself on both its “small state” status and its industrial accomplishments. It was thus a “rich state with a strong military” that refrained from diplomatic and military activity beyond its borders. The True Account summarized the three objectives that guided Swiss national policies as follows: “to safeguard the country’s rights; to refrain from interfering with the rights of other countries; and to prevent other countries from interfering with Switzerland’s rights.” The Mission identified the state’s vow and practice of strict neutrality as the core of its diplomacy:

Switzerland also fosters its military strength. Should there be any upheaval in a neighboring country, Switzerland follows a policy of strict neutrality and does not permit a single [foreign] soldier to come within its borders. If an enemy invades, he is driven back. And since Switzerland also respects the rights of other countries, once a retreating enemy has crossed the Swiss frontier he is pursued no further. The Swiss would never send troops into another country’s territory.30

The True Account acknowledged that geographically, a country surrounded by mountains provided it with a natural protective barrier. Additionally, it recognized Swiss patriotic spirit and the people’s superior craftsmanship as instrumental to the country’s success. The people were also highly skilled in mountain warfare and

would willingly fight to the death to defend the country from foreign invasion, as though fighting a fire. Every household provides a soldier with rifle and uniform…. If a neighboring country threatens invasion, all the people become soldiers…. Despite its small size, therefore, the country’s military strength is regarded with the highest respect among the great powers, and no country would dare try to conquer it.31

Additionally, Swiss women “serve in the commissariat or nurse the wounded.”32

The True Account also noted the state’s superior educational institutions that instilled a sense of patriotism in its people; they cultivated that which is admirable in their history “to foster the spirit of patriotism by indelibly implanting in [the people’s] minds [an understanding of] the process by which the aspirations of earlier generations have been handed down, leading each new generation towards the cultivation of what is admirable.”33 This pride was reflected in the people’s industrial capacity, particularly in areas for which the Swiss had gained a reputation of excellence: watches, jewelry, and textiles. The True Account applauded these talents, as well as Switzerland’s success in creating a society that boasted “an even distribution of wealth among the people of this country, [in which] there are very few poor households.”34

Still, it was Switzerland’s majestic scenery, rather than its unique politics, that impressed the Mission. The True Account devoted a full chapter to descriptions of its mountain terrain, through which the tour had passed.35 The Japanese delegation met frequently with their guide, Hefner Siber, a merchant who had served as Swiss deputy consul to Japan in the years leading up to the Meiji Restoration. The True Account was silent over any advice the tour might have received from Siber or other Swiss officials, particularly with regard to the virtues of small state neutrality. Though recognizing the protection that the Swiss Alps provided the country, it made no mention of whether the Mission saw the seas surrounding the Japanese archipelago as serving a similar function. We do see possible hints of Swiss small-state influence in the tour’s immediate aftermath, when participants took up instrumental roles in overturning plans for an invasion of the Korean peninsula. Additionally, the writing of one student on the tour, Nakae Chōmin, suggests a debate evolving among Japanese intellectuals in the 1880s, specifically over whether their country should adopt large or small state diplomatic practices. However, it is clear that by the end of the century, those who supported the model of a large, expanding state had all but silenced the voices of the minority in favor of the small-state model.

Post-Mission Influences on Japanese Diplomacy

The Iwakura Mission ended prematurely when the tour members received word that the caretaker government they had left in Japan was planning to punish Korea over its negative responses to the Meiji government’s overtures for modernizing the two countries’ diplomatic relations. The new Japanese government had dispatched envoys to the peninsula with a letter from the Meiji emperor, announcing the revolutionary change in Japan’s government and proposing that the two governments revise their diplomatic relations, a gesture that the Korean government rejected.36 In response to this “insult,” government officials secured the emperor’s support for a punitive invasion of the peninsula.37 Objections from members of the Mission initiated what came to be known as the Seikanron, or invade Korea debate. The members’ success in blocking the operation drove Saigō Takamori out of government and back to his homeland in Satsuma (Kyushu), where he led the ill-fated battles of the 1877 Seinan War (sometimes referred to as the Satsuma Rebellion). This revolt reflected a general dissatisfaction among former samurai from this domain, particularly over the direction that the Meiji government was leading the country, as evidenced by the split over the Korean issue.

Mission participants’ refusal to support this operation hints at their favor for a small state diplomacy that they apparently developed during their travels. This opposition to overseas aggression, however, was short-lived, and more indicative of their understanding of Japan’s weak global position compared to that of the states they visited. To embark on such an operation would threaten Japanese sovereignty: it would further increase Japan’s economic dependency on, and possibly invite further intrusion by, the Western powers. The diary of one Mission participant, Kido Takayoshi, reflects the evolution of this thinking. Kido supported invasion at the time of the initial Korean “insult” in 1868. His thinking was less assertive in September 1872, when he learned through the New York Times that the Korean government had detained a Japanese envoy. Even at this time, he supported punishment, but in a more prudent way: Japan must remain “polite and considerate, and explain our intentions fully.” If affronted, however, they needed to act accordingly: Korea “must be opened eventually, even though we might have to resort to arms to affect it.” He reasoned that Japan could adjust the annual costs of such an altercation, which would run between 300,000 and 700,000 yen, to “suit our convenience.” Additionally, he felt that any “trouble [that arose] outside our boundaries” would accelerate Japan’s progress as a nation. He presented these ideas before Vice Minister of War Ōmura Masujirō, who initially “doubted [this] wisdom,” but became a supporter after Kido explained the plan in detail.38 Nearly a year later, however, Kido’s diary reveals a further evolution of his thoughts on the Korea issue. By this time, he confessed to being “deeply disturbed” by the government’s plan to “send an expedition to Taiwan and to subdue Korea,” citing Japan’s unstable domestic situation as the reason to avoid such an operation:

At present, our common people are undergoing hardships; they are bewildered by a myriad of new ordinances, and several times since last year they have risen in revolt. The government apparently regrets this as a moral condition. To speak of planning for the present, nothing is more urgent than proper management of domestic affairs.39

Another Mission participant, Ōkubo Toshimichi, explained his objections to the invasion in terms of the diplomatic crisis it would create. His reasoning suggests influence from his travels across the United States and Europe, and revived the Edo-era fear of the threat Russia posed should Japan engage Korea in war.

Turning to foreign relations, we note that for our country, Russia and England occupy the position of foremost and greatest importance. Russia, situated in the north, could send her troops southward to Saghalien [Sakhalin] and could, with one blow, strike south…. Thus, should we cross arms with Korea and become like two water-birds fighting over a fish, Russia will be the fisherman standing by to snare the fish.

Ōkubo next pointed to the economic debt that Japan already owed England, and how a war with Korea would further inflate this debt, which in turn, would threaten Japan’s national sovereignty.

England’s influence is particularly strong in Asia. She has occupied land everywhere and has settled her people and stationed her troops thereon. Her warships are poised for any emergency, keeping a silent watch, and ready to jump at a moment’s notice. However, our country has been largely dependent on England for its foreign loans. If our country becomes involved in an unexpected misfortune, causing our stores to be depleted and our people reduced to poverty, our inability to replay our debts to England will become England’s pretext for interfering in our internal affairs, which would lead to baneful consequences beyond description.40

He pointed to a third reason to abandon the operation: the urgency underwriting the need to renegotiate, on more equal terms, the treaties that late Edo Japan had signed with the Western powers. Japan, he argued, should focus first on correcting these injustices.

The treaties our countries has (sic) concluded with the countries of Europe and America are not equal, there being many terms in them which impair the dignity of an independent nation…. The time for treaty-revision is well-nigh at hand. The ministers in the present government, by giving their zealous and thorough attention, must evolve a way to rid the country of its bondage and to secure for our country the dignity of an independent nation. This is an urgent matter of the moment.41

Iwakura Mission participants like Kido and Ōkubo, who had witnessed the advance of the Western world firsthand, focused their thoughts here on quelling immediate challenges that Japan confronted rather than argue for Japan’s long-term diplomatic strategy. Japan’s opportunity to pursue a diplomacy of expansion would come soon enough, specifically in May 1874, when the Japanese military crossed over to Taiwan in retaliation for the murder of 54 shipwrecked Ryūkyū sailors, who had been killed by members of the Paiwan tribe. This operation was a clear attempt on Japan’s part to stake claim on the island group, even though its control over the archipelago was in limbo at the time.42 In 1876, the Japanese adopted “gunboat diplomacy” against the Korean government, through which the intruders forced the kingdom into a treaty with unequal political and economic measures, similar to those that the Western powers had forced upon the Edo government – measures that the Iwakura Mission had ambitiously attempted to revise in its dealings with European nations during its world tour.

Alternatives to “Japan as a Large Country” Arguments

From the late nineteenth century, the Japanese government’s military and expansion policies enjoyed popular support among its constituents and the media, suggesting the country’s general approval of large state diplomacy. However, the writings of Nakae Chōmin (1847—1901) depict an active debate on this issue less than a decade prior to the outbreak of the first Sino-Japanese War. One of the students in the Iwakura Mission, Nakae was dropped off in Lyon, France, where he studied until May 1874. After returning to Japan, he started a French language school and participated in the founding of the Tōyō Jiyū shinbun (Oriental Free Press). Moreover, he translated the works of French philosophers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Nakae assumed an important role in the minority Jiyūtō (Liberal Party), which was among the leading political voices calling for pan-Asian unity among Japan’s northeast Asian neighbors, particularly China and Korea. In 1887, he published A Discourse by Three Drunkards on Government (Sansuijin keirin modō), which summarized the two popular discourses about Japan’s diplomatic relations, before introducing a third, alternative view.

Figure 7: Nakae Chōmin, A Discourse by Three Drunkards on Government

(三酔人経綸問答Sansuijin keirin mondō), 1887.

Nakae characterized the debate over Japan’s foreign policy as between followers of a diplomatic (small) or militaristic (large) approach. He argued that neither approach would grant Japan the national security it desired. His discussion introduced these options in the form of a disjointed dialogue between three drunkards. He named the first drunkard Mr. Gentleman. Outfitted in European attire, Mr. Gentleman argued that the best way for Japan to preserve its security was for it to develop strong diplomatic relations with the Western powers. Japan must accept its reality as a small nation and develop its foreign policy accordingly.

Why shouldn’t we, a small nation, use as our weapon the intangible moral principles our opponent aspires to but is unable to practice? If we adopt liberty as our army and navy, equality as our fortress, and fraternity as our sword and cannon, who in the world would attack us?43

Japan should establish “precedent” by refusing to join the arms race and foregoing attempts to match the military power of its opponents. Joining in this game would invite armed invasion, which could result in foreign occupation. When challenged over what a nation should do if attacked, Gentleman retorted that in such an unlikely occurrence, the unarmed nation would “calmly state, ‘We have never committed any incivility against you. …. We have no internal disputes in the harmonious workings of our government. We do not want you to disturb our country. Please go home immediately.’”44

The second drunkard, Mr. Champion, attired in native Japanese dress, was beside himself in laughter over Gentleman’s “simple-minded tale.” Japan faced constant threat “unless we build up the number of soldiers and battleships, increase our nation’s wealth, and enlarge our land. Haven’t you learned from the examples of Poland and Burma?”45 His realpolitik-laced argument continued with his promotion of a large-country diplomacy that depended on expansion to preserve Japan’s national sovereignty.

If we are willing to give up our nation’s savings, we should be able to buy at least several dozen to several hundred battleships. If we send soldiers to fight, merchants to trade, farmers to cultivate, artisans to manufacture, and scholars to teach, and if we take a half or a third of [a certain large, but weak, country] and make it part of ours, our nation will suddenly become large.46

As for the Japanese islands, “we will let a foreign country take [them] if anyone cares to.”47

Master Nakai, no doubt Nakae himself, found flaws with both arguments, which he saw as being “poles apart”:

Mr. Gentleman’s ideas are pure and righteous; Mr. Champion’s ideas are uninhibited and extraordinary. Mr. Gentleman’s ideas are strong liquor that makes me dizzy. They make my head spin. Mr. Champion’s ideas are harsh poison that rends my stomach and rips my intestines.48

Nakai proposed a third option that reflected Swiss influence, though it also strayed from the Mission’s impression of neutral diplomacy. He advised that Japan should forge alliances with its neighbors. Domestically, he advised the creation of a bicameral upper and lower house parliament, similar to the one that Japan would establish in a matter of years. In response to the polemics proposed by Gentleman and Champion, Nakai put forth the following as the ideal approach for Japan’s diplomatic affairs:

In framing diplomatic policy, peace and friendship should be the basic rule. Unless our national pride is damaged, we should not act in a high-handed manner or take up arms. Restrictions on speech, publication, and other activities should be gradually eased, and education, commerce, and industry should be gradually promoted. Or something like that.49

His one detour from the idealist vision of Swiss diplomacy better reflected his country’s present reality in suggesting that the Asian states form an alliance: Japan should ally with China to guarantee its national security concerns, on the condition that the two states “become brother nations sworn to help each other in an emergency.”50 This last point reflected the pan-Asian thinking espoused by members of his minority Liberal Party at the time.51

Conclusion

The Iwakura Mission participants returned to Japan with plans for instilling people with the industriousness and patriotism necessary for nation building. As Iwakura observed at the beginning of this paper, this ambition was possible regardless of whether the state remained small and neutral, or whether it expanded its influence outside its borders. As the Mission observed in Switzerland, the two characteristics were linked: An industrious people also developed a reverence for their country, which would, in turn, encourage them to protect the state should outside forces threaten its sovereignty. Kido Takayoshi and Ōkubo Toshimichi returned from the Mission to warn of the perils that Japan would face should it engage in large-state military activity, at least at this early stage in Japan’s development. Later, Itō Hirobumi would attempt to coordinate a less intrusive protectorate arrangement in Korea, rather than annex the peninsula outright. He would, however, come to accept annexation in 1909, when it became apparent that his approach did not provide Japan the degree of control he felt it needed.52 Nakae Chōmin’s essay captured a late nineteenth-century debate by outlining three diplomatic approaches: one alliance-centered, another expansion-centered, and a third Asian union-centered. By this time, the absolute neutrality policy that the Mission had observed in Switzerland was no longer an option for post-Restoration Japan. A little more than a decade after the Mission’s return, Japan’s first prime minister, Yamagata Aritomo, opened the new Japanese Diet in 1890 with a speech that outlined Japan’s foreign policy in two lines: a line of sovereignty (shukensen) and a line of interest (riekisen), in which he all but provided a recipe for war. In this speech, the field marshall emphasized the need for Japan to extend its line of interest in tandem with its line of sovereignty.53 We see Yamagata’s dual lines of expansion materializing in the aftermath of Japan’s victories in its wars with China (1894—1895) and Russia (1904—1905), victories that led to Japan’s further expansion onto the Asian continent.

Occasionally, Japanese intellectuals would challenge the logic of this strategy. Miura Tetsutarō (1874—1972) argued that the military expense increases in the wake of the two wars had led to devastating budget cuts. These increases in spending had severely depleted the state’s capacity to advance its subjects’ livelihood. Clearly an advocate of a smaller and less intrusive Japan, Miura concluded his essay by describing the fantasy underwriting the policies – a fantasy that had ensnared people within a “grand illusion” of large Japanism or Dainipponshugika.

Figure 8: Miura’s Dai Nihonshugi ka ko nihon shugi ka.

Ralph Norman Angell once argued that countries have become caught up in the grand illusion that war increases a state’s wealth and power, that it serves as a measure of a nation’s development. His thinking continues to have a big influence on world thinkers. However, we judge the impact of the two great wars, in which our country has fought, on the basis of the management of new territories acquired. This grand illusion has served in thought, politics, and economics as a massive foundation that has advanced a policy of large Japanism. Also, such a policy is vigorously advanced to the issues of military affairs and new territory management. This argument is one that [the Tōyō Keizai shinbun] has appropriately entertained many times. We will return to this on another day, but here, we simply point out the damage of large-Japanism in the hopes that it provokes serious reflection [on the direction that Japan’s diplomatic policies have led the country].54

Miura would live to see Japan’s dainihonshugi expand ever deeper into the Asian continent, and nearly lead to his country’s complete destruction by war. He no doubt welcomed the 1945 Potsdam Declaration that redrew postwar Japan as a small state limited primarily to its four main islands—Honshu, Hokkaido, Kyushu, Shikoku—while leaving open the possibility of minor islands being added the Japanese territory in the future. He most likely drew a sigh of relief upon reading the “peace” constitution that (on paper) eliminated the potential for Japan’s overseas military activity.

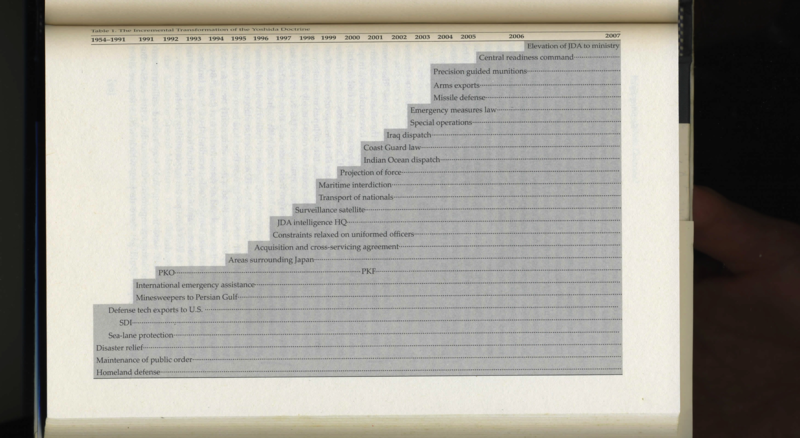

Any optimism Miura might have felt in the immediate postwar period surely would have dissipated by the time of his death in 1972, as Japan gradually peeled away the military constraints that had been entered into this constitution. The United States begun to push for Japan’s remilitarization from 1948 onwards, as U.S.-Soviet relations deteriorated and Cold War tensions rose. These efforts gained momentum with the outbreak of the Korean War in June 1950, when the Japanese government formed the National Police Reserve, the forerunner to the Self-Defense Forces. Miura did not live to witness the more recent increases in military budgets and weapon advancement, nor the deployment of Japanese troops overseas. The past seven decades of postwar Japan resulted in strong military ties between the U.S. and Japan under the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security (first signed in 1952), the strong military presence of U.S. bases spread across the archipelago, and general Japanese subordination to U.S. power.55 These developments have resulted in a gradual, but steady, hollowing out of Japan’s image as a peaceful country, to return it to the large-state politics introduced over the Meiji-era, albeit in a contemporary context.56 Conservative governments continue to argue the need for the archipelago’s resurrection as a “normal [large] country,” in former Prime Minister Nakasone Yasuhiro’s words an “unsinkable aircraft carrier,” armed with the capacity to defend its national interests on both domestic and international fronts. The current bearer of this ambition, Prime Minister Abe Shinzō, battles popular opposition to fully return Japan to its prewar status, namely by relieving it of the thin constraints remaining from Article 9 of Japan’s postwar constitution.

Figure 9: “Article 9’s Slow Death,” Samuels, p. 93

Click to expand.

Notes

Iwakura Tomomi quoted in Igarashi Akio, Meiji ishin no shisō (Ideology and the Meiji Restoration) (Yokohama: Seori shobō, 1986), 145.

Kume Kunitake. The Iwakura Embassy, 1871–73, a True Account of the Ambassador Extra-ordinary Plenipotentiary’s Journey of Observations Through the United States and Europe. 5 vols. Edited by Graham Healey and Chūshichi Tsuzuki. Chiba: The Japan Documents, 2002.

For example, Akira Iriye, Pacific Estrangement: Japanese and American Expansion (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1972), 35.

Brett L. Walker, The Conquest of the Ainu Lands: Ecology and Culture in Japanese Expansion, 1590—1800 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001), 227-28.

A partial translation of Honda’s work is found in Donald Keene, The Japanese Discovery of Europe, 1720—1780 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1968), 180, 203.

See a translation of this work in Bob Tadashi Wakabayashi, Anti-Foreignism and Western Learning in Early-Modern Japan: The New Theses of 1825 (Cambridge, Mass: Council of East Asian Studies at Harvard University, 1986), 250.

Quoted in David M. Earl, Emperor and Nation in Japan: Political Thinkers of the Tokugawa Period (Seattle: University of Washington, 1964), 174.

The other three were Kido Takayoshi (Vice-Ambassador), Nomura Yasushi (Foreign Ministry), and Yamada Akiyoshi (Military Affairs).

Roger F. Hackett, Yamagata Aritomo in the Rise of Modern Japan, 1838—1922 (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard East Asian Series, 1971), 51-54.

I describe these three forms of expansion—internal, peripheral, and external— in detail in my Japanese Assimilation Policies in Colonial Korea, 1910—1945 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2009), 6-12. France was unique in declaring its intention to assimilate people in its African colonies. This produced a backlash from Social Darwinists in particular, who argued that attempts to introduce “primitive” peoples to “advanced” institutions would be futile. For these arguments, see Raymond Betts, Assimilation and Association in French Colonial Theory, 1900—1960, trans. William Glanville Brown (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1991), 64-69, 147-52.

Kenneth B. Pyle offers a comprehensive summary of the Iwakura Mission’s realization of this “catch-up vision” in his The Making of Modern Japan, second edition (Lexington, Mass.: C. C. Hearth and Company, 1996), 98-101.

See Grace Elizabeth Hale’s Making Whiteness: The Culture of Segregation in the South, 1890—1940 (New York: Vintage Books, 1998) for a discussion on Reconstruction-era black schools.

Ibid. The Japanese appeared to be overwhelmed with the Highland scenery, which occupied much of the space in that chapter.

Ukita Kazutami, “Kankoku heigō no koka ikan” (What are the Effects of Korean Annexation?), Taiyō (October 1, 1910). This observation did not reflect historical reality as the Scottish people had launched anti-English rebellions, as well, in the past.

The two most prominent voices calling for an end of colonialism were Soviet Chairman Vladimir Lenin’s 1917 publication Imperialism, The Highest Stage of Capitalism and U.S. President Woodrow Wilson’s call for “self-determination” in his fourteen points speech of 1918. Albeit unsuccessful, Franklin Roosevelt used his meetings with Winston Churchill during the Second World War, along with Joseph Stalin’s support, to implore the prime minister to liberate his country’s colonies.

The “father of the Japanese museum” was Machida Hisanari (1838—1897), who studied in Europe for two years from 1865, during which time he became familiar with the museum through visits to London’s British Museum and the Louvre in Paris. See Seki Hideo, Hakubutsukan no tanjō: Machida Hisanari to Tokyo no teishitsu hakabutsukan (The Birth of the Museum: Machida Hisanari and Tokyo’s Imperial Museum) (Iwanami shinsho, 2005).

Ibid. Colonel Eugéne Stoffel, who spent time in Prussia before the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War, argued after the war that the Prussian education system had disseminated “a strong sense of duty through the Prussian people,” and was a deciding factor in the war. See his “A French View of the Prussians,” The Nation (March 30, 1871).

The Mission may have been encouraged by the success that a Chinese mission had in revising similar treaties that they had signed with the United States. For an account of the “‘Burlingame Mission” see John Schrecker, “For the Equality of Men—For the Equality of Nations’: Anson Burlingame and China’s First Embassy to the United States, 1868,” Journal of American-East Asian Relations 17 (2010): 9-34.

Kume, The Iwakura Embassy V, 45. This view of Switzerland’s neutral foreign policy was a rather idealist interpretation that did not precisely match Swiss involvement in the recently concluded Franco-Prussian War (1870—1871), or other incidences of Swiss interaction with its neighbors. For Swiss history around this time, see Clive H. Church and Randolph C. Head, A Concise History of Switzerland (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2013), Chapter 6.

The Korean government rejected the inquiry as it came from Tokyo, rather than the Tsushima domain that handled Edo-era relations with the peninsula. It also carried the character for ko (皇) that could be used only for the Chinese emperor, as stipulated in the two countries’ Sino-centric relations.

Saigō’s arguments are found in “Saigō Takamori: Letters to Itagaki [Taisuke] on the Korean Question” appears in Sources of Japanese Tradition Vol. 2, Ryusaku Tsunoda, Wm. Theodore de Bary, and Donald Keene, eds. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1958), 147-51.

Kido Takayoshi, The Diary of Kido Takayoshi Vol.II: 1871–1874, trans. by Sidney D. Brown and Akiko Hirota, (Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press, 1985), 206.

Ōkubo’s arguments are found in “Ōkubo Toshimichi: Reasons for Opposing the Korean Expedition,” in Sources of Japanese Tradition II, 151-55.

Ibid. Other reasons offered by Ōkubo include the suddenness and incompleteness of the Restoration, the distractions the expedition would cause in delaying the government’s ability to address more immediate matters, and the impoverishment of the country that would result from the expedition.

Robert Eskildsen, “Of Civilization and Savages: The Mimetic Imperialism of Japan’s 1874 Expedition to Taiwan,” The American Historical Review 107 (2, 2002): 388-418.

Nakae Chōmin, A Discourse by Three Drunkards on Government, trans. Nobuko Tsukui (New York: Weatherhill, 1984), 51.

Nakae made no mention of Korea at this point, but just two years previous, another member of his political party, Ōi Kentarō, faced trial for his involvement in the Osaka Incident (Osaka jiken), which involved Ōi’s attempts to raise funds to support the Korean reformer Kim Okkyun as he led the Kapsin coup attempt of 1884.

Itō’s assassination in October 1909 by An Chunggŭn left many unanswered questions regarding the former Resident General’s ideas about future Korea-Japan relations. It is also difficult to ascertain the extent to which his experiences in his early travels with the Iwakura Mission influenced his views on Korea. For assessments of Itō’s tenure in Korea as Resident General, see Hilary Conroy’s The Japanese Seizure of Korea, 1868—1910: A Study of Realism and Idealism in International Relations (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1960), especially 334-82; and Peter Duus, The Abacus and the Sword: The Japanese Penetration of Korea, 1895—1910 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), especially Chapter 6.

Matsuo Takayoshi, ed. Dainipponshugika shonihonshugika: Miura Tetsutarō ronsetsushū [Big Japanism? Small Japanism? A Collection of Miura Tetsutarō Essays] (Tokyo: Tōyō Keizai shinbunsha, 1995), 145, 173-74.

Kenneth B. Pyle offers an interesting discussion on this lingering influence of the seven-decade postwar U.S. occupation on Japan in his “The Making of Postwar Japan: A Speculative Essay,” Journal of Japanese Studies 46, no. 1 (Winter 2020): 113-43.

Richard J. Samuels graphically demonstrates “Article Nine’s Slow Death” in his Securing Japan: Tokyo’s Grand Strategy and the Future of East Asia (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2007), 93.