Abstract: Freelance work has proliferated in Japan over the last decade due in part to the Abe administration’s encouragement of work style reform to reinvigorate the economy. However, freelancers have heavily criticized the government for treating them unequally in their compensation program for workers affected by the coronavirus. The COVID-19 pandemic and emergency declaration have exposed freelancers’ employment insecurity and lack of access to a social safety net during an economic crisis. Intense debates have erupted on social media about how much companies and the government should be responsible for freelance workers’ welfare. Defenders of providing lower levels of compensation to freelancers draw on pre-existing neoliberal arguments that freelancers, like other irregular workers, are personally responsible (jiko sekinin) for themselves. However, many freelancers have pushed back by arguing that freelance work has become so mainstream that it no longer makes sense to treat it as some unique and separate work category. Being technologically savvy, freelancers have quickly leveraged their familiarity with social media platforms to criticize the unequal economic compensation and to demand increased benefits and recognition for their work in a surprising act of political defiance.

Keywords: COVID-19; vulnerable populations; freelance; precarity; self-responsibility (jiko sekinin); freeters.

Many of Japan’s freelance workers are struggling. Writing in the online lifestyle website, Mi-Mollet, freelance fashion editor, Takahashi Kanako, explains that her work is rapidly vanishing. She writes, “ever since the emergency declaration was announced, all my photoshoots planned this month had been canceled. Not only projects with Mi-Mollet, but with other fashion magazines, and books in progress…in total seven photoshoots were canceled!!” For Takahashi, this situation is unprecedented. She explains that “I’ve been working as a freelancer for a long time, but this is my first time experiencing something like this” (Takahashi 2020).

The Covid-19 pandemic has had a sudden and dramatic impact on freelance work in Japan. According to an Intloop survey, 85% of freelance workers answered that “their work has been reduced,” and 77% reported that they “feel the aftershock” of the COVID-19 pandemic (Intloop 2020). According to another survey from CrowdWorks Inc, an online crowdsourcing service for freelance workers, more than 30% of freelance workers have reduced their income about 50,000 JPY per month, while more than 15% report that their monthly income has reduced by at least 100,000 JPY (CrowdWorks 2020). Overall, Japan’s unemployment rate for March and April is about 2.5%, which is quite low by international standards, but the highest rate in Japan since 2017. Some projections see the unemployment rate rising to as high as 4% in the next few months which will put pressure on the Abe administration to respond since any rise in the unemployment rate is politically sensitive (Reuters 2020). The more significant shift in the Japanese labor market is that roughly seven million workers, about 9% of the workforce, were on leave (kyugyo) in March and April, including furloughed employees and those on parental leave (Nikkei 2020), the highest number since 1967 (News Week Japan 2020). It is possible that up to one million jobs will be lost by the end of the year (Japan Times 2020).

However, the unemployment rate and reports about workers on leave alone do not tell the whole story. As some freelance work disappears under the emergency declaration, new freelance jobs, often ones with more direct personal risk, are increasing. Freelancers must abruptly change course, requiring maximum personal flexibility, to respond to the economic upheaval if they want to keep earning income. For instance, a DJ based in Osaka writes on his blog that since April, his life has been basically turned upside down by Covid-19. Narrating his experiences, he writes that “ever since the postponement of a club event at Kyoto Metro on March 13th, all of my work has just disappeared. Since this was my primary job, I basically lost everything” (Sekitova 2020). He’s had little choice but to take new part-time jobs as a security guard, as a remote data entry clerk, doing food delivery, and picking up small side jobs related to music. Although he’s been able to find new employment, he remains anxious about whether these temporary solutions will become permanent. He explains that “although there are part-time jobs available, I never know when they might end too…I’m anxious about whether I will be able to return to music as my main source of work.”

The pandemic has quickly and quite dramatically exposed freelancers’ vulnerabilities in the labor market. Before the pandemic, working remotely was one of the main advantages freelancers enjoyed over salaried workers. Unlike full-time employees who typically worked long hours in offices, specific categories of freelancers like writers, artists, designers, and consultants could work from home according to their own schedules. However, in the upheaval of the pandemic, many freelancers are watching in dismay as their work vanishes as full-time employees (seishain) for big companies transition to telework from home. Some mid-sized to small companies (chusho kigyo) are also following the larger corporations’ example in encouraging teleworking. Japanese companies have not responded uniformly, with some stubborn holdouts remaining committed to having employees still report in person to their office during the pandemic (Washington Post 2020; Yahoo News 2020a). Yet it appears that many freelancers are being cut off as companies quickly reorganize in response to the emergency declaration by prioritizing their salaried workers. The flexibility that freelancers enjoyed during better economic times also concealed their precarity. The pandemic has rapidly revealed freelancers’ fundamental employment insecurity and lack of safety net. Consequently, the situation has set off a vigorous online debate about how much Japanese society values freelancers, whether freelance work is sustainable, and unexpectedly, its potential as a form of political resistance.

The Growth of Freelance Work

The Japanese government defines a freelancer as “a person who uses their expertise and skills to receive compensation independently without affiliation to a specific company or an organization” (METI 2018, 5). Freelance work has increased significantly in Japan in the last decade. According to the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare’s 2018 Freelance White Paper, there were reportedly over 10 million freelancers (including those with side-jobs) in Japan in 2018 (Freelance Association 2018, 3). In 2019, freelance work increased by five percent in just one year to 11.2 million workers. It is estimated that one in six of the total number of the domestic labor force are now freelancers (Ozy 2019). According to a top Japanese crowdsourcing service, by 2027 more than half of the population is expected to be freelance workers (The Atlantic 2018)—a staggering projection indicating a sharp departure from the more normative “lifetime employment” system of Japan Inc.

In 2016 the Japanese government formed a labor reform panel and produced “The Action Plan for the Realization of Work Style Reform” (Hatarakikata Kaikaku). At the center of the reforms was a promotion of “flexible work styles.” The plan encouraged companies to remove the common practice of banning moonlighting for their employees, reforming rules around telecommuting, and increasing the number of freelance positions (Council for the Realization of Work Style Reform 2017). The reforms also included “Japan’s Plan for Dynamic Engagement of All Citizens (Ichioku Soukatsuyaku Kokumin Kaigi),” which called on every Japanese citizen to find fulfillment through work as the path towards national economic regeneration:

The greatest challenge towards the revitalization of Japan’s economy is work-style reform. How we work is a synonym for how we live. Work style reform is at the heart of Japan’s corporate culture and is rooted in the lifestyle of Japanese people and Japan’s way of thinking in regards to work…Work style reform aims to enable every worker to have the hope of a better future (The Council for the Realization of Work Style Reform 2017, 2).

Although the government’s messaging on work reform strikes an optimistic tone, what constitutes “a better future” remains a vaguely defined promise justifying the reorganize of the employment system. Former Minister of Economy, Trade, and Industry (METI) Hiroshige Seko explained that “‘Work style reform’ (hatarakikata kaikaku) is the biggest challenge for the Abe Administration. Flexible work–not measured by time, place, and contract–such as ‘side-jobs’ and ‘freelance’ will be the key to work style reform” (METI 2018). Seko continued, “to make the Japanese economy grow, we cannot depend only on the ‘Japanese Employment System,’ but also need those working ‘side-jobs’ and as freelancers” (METI 2018). While often considered outside of the “regular” track and indeed labeled as irregular labor (hiseki), in fact, the goal of these reforms was precisely to develop this new sort of labor. Although the Japanese Employment System centered on the salaryman model, it never actually applied to most Japanese workers. Nevertheless, here we see an image of economic revitalization that is not premised on the redoubling of individual sacrifice directed to the corporation–a very Japan Inc. model. Instead, what we see is, in many ways, the opposite; encouragement of the individual to pursue their own “better future” through a work style that brings the individual away from the obligation and protection of the company.

These reforms promised better work-life-balance. The managers of large corporate companies were encouraged to reduce the amount of overtime work they typically demanded of their full-time employees in exchange for an increased supply of freelance workers under relaxed labor regulations. One estimate is that freelancers could save companies as much as 30 percent per year and reduce the businesses’ risk since freelancers are not official employees (Ozy 2019); as a result, freelance opportunities expanded rapidly under the government guidelines. While the wage will depend upon the particular job, the overall savings comes from the fact that benefits, including retirement premiums and health insurance, are not paid for by the company.

Freelance opportunities expanded rapidly under government guidelines. Between 2015 and 2018, freelance work grew by 23 percent (Zoho 2018; Lancers 2018b). Full-time workers, too, with more free time as a result of reduced over-time work, also began to work as “side-hustlers” (Fukugyo), to earn extra money. In 2018, there were an estimated 2.7 million people who were supplementing their income, working mostly from personal computers, writing articles, inputting data, or selling their expertise, etc. (Mizuho 2018). This is in effect a sort of familiar trade-off; the salaried elite (full-time workers) get reduced hours as the workload is shifted to cheaper and more flexible work contracts–more flexible for the corporation. This is consistent with the sort of labor shifts we see occurring in neoliberal economies where the governance structure aids and abets market deregulation, leading to more precarity.

Lancers, one of the top crowdsourcing services for freelance workers in Japan, surveyed freelancers asking them to describe some of their work’s defining characteristics (hatarakikata). What they reported was that freelancers in the survey used the terms’ freedom’ (jiyu), ‘professionalism’ (purofesshonaru) and ‘rewarding’ (yarigai), in addition to ‘self-responsibility’ (jiko sekinin) and ‘unstable income’ (fuantei) (Lancers 2018a). Lancers interpreted these responses to mean that “many of the freelance workers believe that to enjoy freedom in their work, it requires self-responsibility (jiko-sekinin), such as learning skills by themselves.” The Lancers report accentuated “self-responsibility” and hard work as the qualities needed to win their freedom by drawing on the following examples:

I can freely work based on my own decisions, and if I succeed, there’s going to be a big payday. But, I need to search for my work constantly, so I think it’s the type of work that is very difficult to keep a stable income (Male, 30s, Side-job Freelancer).

As we can see, the other side of freedom is not just hard work but also a risk, the ability to tolerate risk, and the commitment to continually search for work.

This is a way of life that does not rely on a company. I can work by managing myself with my own decisions. The achievements are very different. I am still learning about them, and still don’t have all of the results, but it would be great if I can achieve them (Male, 60s, Freelance Worker (Jiyuugyo-kei Furii Waakaa).

It also requires that the self becomes the site of continual refinement, a sort of project that is the focus if results are to be achieved, in this case, even at 60 years old.

Despite the government’s push to expand freelance work, there are many reported problems associated with it. Freelancers complain that companies take advantage of them (Deutsche Welle 2018). Companies do not provide freelancers with benefits or social insurance, thereby reducing their employment costs and minimizing risks in having to support their workers during economic downturns (Zoho 2020). Instead of being treated as professionals with specialized skills, companies sometimes use freelancers more as a source of cheap labor or underpay for their skill set. Verbal agreements, instead of formal contracts between freelancers and companies, often the norm, can lead to misunderstanding or abuse. A staggering 62% of freelancers report that they have been subjected to “power harassment” (Ozy 2019). Freelancers also suffer from credibility problems. Companies often avoid hiring former freelancers into full-time positions, judging them as less reliable. Banks and financial institutions often see them as too risky to secure business or personal loans (Japan Times 2017). Despite the government’s promotion of freelance work, the Japanese corporate work culture does not reward freelancers in the same way it does with full-time employees.

Millennial Workers

Most everyone–politicians, youth, and older workers–agree that the Japanese labor market and corporate culture need reform. The Action Plan for the Realization of Work style Reform rightly acknowledges many points of friction within the employment system requiring change, including long working hours, uncompensated overtime, and a rigid hierarchy that is often seen as discouraging innovation. While the work-style reforms improved full-time employees’ work-life balance in reducing overtime, opening up the possibility of working side jobs, and making telework a possibility—as well as opening opportunities for rewarding leisure or family and life—it affects the freelancers, most of them being younger workers, who are paying the price.

Many of the freelancers are Millennials (b. 1980-1994) with some born after the bursting of Japan’s economic bubble in the early 1990s and growing up during the lost decades of the 1990s and early 2000s (ushinawareta 20 nen). Disasters have typified this younger generation’s lives. They experienced growing up through two significant earthquakes in Kobe in 1995, and the 3.11 Tohoku Earthquake, tsunami and Fukushima Nuclear disaster in 2011. This generation has also suffered two global economic crises with the Lehman Shock in 2008, and now the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020. The normative “salaryman” model of working in the same company until retirement more familiar to their parent’s generation’s aspirations is something beyond reach for most younger workers just entering the labor market. These youth orient themselves toward gaining work experience and learning special skills to navigate an unstable work environment. Unlike their parent’s generation, job-hopping, head-hunting (tenshoku), and working for themselves are how they move through the labor market. Working as “nomads” or “freelancers” with a laptop in co-working spaces has snowballed in urban areas in the late 2010s in part in response to “The Action Plan for the Realization of Work Style Reform.” Moreover, young workers often idealize images of young, successful IT company CEOs and entrepreneurs. Some dream of becoming the next Steve Jobs or Elon Musk as the way to escape their toxic bosses and the many mind-numbing years they expect to endure to achieve success (Uno 2017).

State Management of “Self-Responsibility” (Jiko Sekinin):

Conflating Work with Citizenship

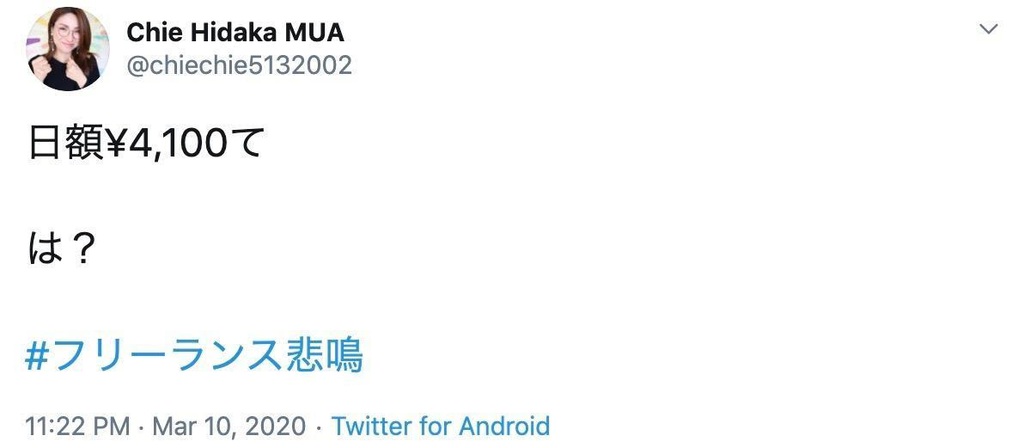

Although younger workers have adapted to a more precarious labor market without any significant revolt, the government’s public aid response to the coronavirus pandemic might be a turning point. The Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare offered a leave compensation program for workers who needed to take time off to care for their children. This was because of the nationwide closure of schools during the emergency declaration. However, the aid was uneven, greatly disadvantaging a large and growing number of non-regular workers. The Ministry compensated companies up to 8,330 JPY per person per day from employment insurance (Asahi Shimbun 2020a). However, freelancers, ineligible to receive subsidies through companies, could apply to the government to receive only up to 4,100 JPY per person per day, and up to 200,000 yen in emergency loans (Asahi Shimbun 2020b). Moreover, those working in nightclubs, entertainment venues, restaurants, and the sex industries were initially completely excluded from receiving any public funds (Mainichi 2020). After some controversy they became eligible to apply under certain conditions (CNN 2020). The unequal distribution of government aid was quickly denounced as discriminatory by critics and seen as communicating a value judgment on the relative value of workers based on their varying levels of entitled benefits. Many freelancers took to Twitter to criticize the government’s response.

|

¥4,100 per day. What? #Cry of Freelance. (Twitter: @chiechie5132002, March 10, 2020) |

Online arguments about what constitutes fair compensation for lost work and which workers are ultimately more deserving than others quickly coalesced around the notion of “self-responsibility” (jiko sekinin). Defenders of the lower compensation for freelancers argued that since they “chose” this style of work, they needed to take “responsibility” for the consequences, win or lose, and thus take care of themselves instead of looking towards corporations or the government for handouts. Since freelancers are independent workers managing themselves, their position is that neither the government nor companies are responsible for the workers’ welfare. The logic is difficult to catch exactly. Do they imagine that because a freelancer does not work for a company, he or she should be responsible for the effect of COVID-19 in a way that a company employee is not? Non-arguments such as these which conflate the state and corporation reveal the low esteem in which the government holds freelancers, despite their championing of these same freelancers in recent reforms

The online streaming channel, Abema TV News, owned by the Asahi TV Network, aired a program on April 21, 2020, about the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on freelance workers (Abema 2020). The program devoted a segment to the question of “self-responsibility” (jiko sekinin). Yuuki Kabumoto, the CEO of start-up StockSun, also known as “The King of Freelance,” argued that freelancers should rely on their wits for survival instead of being given handouts. Kabumoto discussed the following:

I’m a freelance worker too, and I have seen people around me see their pay reduced by 30% to 50%…And in the end, it is all about ‘supply and demand.’ If the companies cancel their contracts because the unit price they are looking for does not meet the demand, lower your unit price. Tell the companies that ‘I will work at a tenth of an hour’s wage,’ to keep your contract. If you say ‘I will work for 100 yen per hour,’ there will be so many companies hiring you!

Whatever the validity of Kabumoto’s argument in normal times, the whole premise behind supplemental government aid is that a crisis has disrupted the supply and demand cycle. For this reason, the state steps in to keep everyone from spinning into economic freefall. Takanori Fujita, who runs the NPO group “Hotto Plus” that supports the homeless and vulnerable workers, countered Kabumoto’s argument. Fujita held that doubling down on “self-responsibility” (jikosekinin) is not the best way for freelancers to weather the pandemic. Instead, he emphasized the importance of businesses and the government’s “social responsibility” (shakai sekinin). Fujita explains:

Yes, there are risks in choosing your work. But, not helping when needed, is a different story. If the country encourages freelance work, then it should not treat it differently…Even those who are unable to make money or take time to do so are also part of society and deserve support. Japan just has weak social security.

Fujita further explains that companies and the state also bear some responsibility towards freelancers and other irregular workers’ welfare in times of economic upheaval. Since the government is actively promoting freelance work, and companies are increasingly employing these workers, it is unfair, in Fujita’s opinion, to provide them with fewer benefits and support than full-time workers receive.

The Abema news program provoked an online backlash from freelancers and others upset at the characterization of freelancers as solely responsible for their financial hardships during the pandemic (Yahoo News 2020). One Twitter commentator expressed dismay at the characterization of freelancers on the program:

|

Today’s Abema TV program described ‘Freelancers as the people who pursue dreams,’ and debated whether their struggles are justified by ‘self-responsibility.’ Freelancers are now just a group of ordinary workers and not some group of dreamers. I’m shocked to see that the media coverage is too divorced from reality. (Twitter: @konno_haruki, April 21, 2020). |

The quote above shows how freelancers are challenging what many of them see as shallow characterizations that misconstrue their motivations for engaging in freelance work in the first place. Freelance work has become so commonplace in the labor market that it is just “ordinary” (普通), as the commentator above describes it, instead of being some kind of special category of workers that should be treated differently, and worse. According to this logic, the following tweet questions why freelancers should be treated any differently than other workers during the emergency declaration:

|

Theories are hanging around saying that ‘Freelancers are responsible for themselves,’ but Freelances also pay taxes, and have the right to say, ‘Do something about it….’ (Twitter: @yoppymodel, March 17, 2020) |

Arguments that freelancers should somehow be held more personally responsible for their successes and losses than full-time workers, as the debates about “self-responsibility” (jiko sekinin) suggest, are separate from the question of the coronavirus crisis. And as the comment above indicates, freelancers are fully contributing members of society and the state tax base, and as such, should not have to forfeit any rights as citizens.

Freelancers, accustomed to working with online platforms, quickly used social media to share their opinions, experiences, and outrage. The Twitter hashtag #フリーランス悲鳴 (#Cry of Freelance) began trending for this purpose. Some used the hashtag to report how much work they lost:

I’m well aware, but I chose to be a freelancer. My income was ten times greater by working relentlessly with no holidays. But my income became 1/10 because of Corona… (Twitter: @taiyaki3150, March 4, 2020).

Others used the hashtag to articulate more focused political criticisms to explain why freelancers deserved more compensation and support from the government:

|

“Some say that we should have known that becoming freelancers would ultimately depend on our self-responsibility. We wouldn’t expect anything from the company under normal circumstances, but this is more like a natural disaster. So all workers should get something from the government.” (Twitter:@ponpoko_Reverse. March 5, 2020). |

What we see here is a conflation of the market and society. First, there is a policy shift to encourage a sort of precarious labor, freeing the companies from the responsibility for the livelihoods of the people who are providing this labor. What the Covid-19 pandemic reveals is that worker’s precarity is compounded in times of crisis, but is explained away using the market logic of self-responsibility. But to deny these workers the full support that all citizens, indeed, residents, are to receive is to conflate their status as workers with their status as citizens.

Freeters (フリーター) and Freelancers (フリーランス)

These arguments are reminiscent of debates surrounding freeters during the bursting of Japan’s economic bubble in the early 1990s, and during the Lehman shock in 2008. Freeters (フリーター) are typically understood to be young people who drift from job to job. The Japanese government defines freeters as youth aged 15-34 who work at one or more part-time jobs or at one short-term job after another (METI 1992). They have been part of the Japanese employment system since the late 1980s. It was an advertising executive working at the free employment magazine “From A” who invented the term during this period. The idea was to devise a word to convey a sense that part-time, temporary, and other non-regular jobs were a hip and fashionable way to earn some money without the substantial commitments demanded by full-time employment (O’Day 2012). When jobs were plentiful at the height of the bubble economy in the 1980s, being a freeter was an attractive alternative for some young people. At least initially, some saw freeters somewhat romantically as a group of young dreamers (artists, creatives, entrepreneurs, etc.) working side jobs to pursue alternative lifestyles. However, when the bubble economy of the late 1980s burst in the early 1990s, creating recession and then economic stagnation, freeter work mostly lost its appeal and viability because of the financial stress and social exclusion that accompanied recession.

The public imaginary of freeters overlapped with how many companies responded to the economic downturn by reorganizing their labor force as part of their competitiveness strategies (Mouer & Kawanishi 2005). Many companies moved away from hiring new graduates into permanent career tracks in favor of using more part-timers, dispatched workers and contract workers with lower personnel cost and higher employment flexibility (Honda 2005:7). Rather than mass layoffs of its full-time employees, many Japanese companies instead either stopped hiring new full-time employees altogether or significantly reduced the numbers of recruits (Abegglen 2006; Genda 2001, 2005). The opportunity to obtain a secure full-time job was reduced considerably for the generation of young people entering the workforce during this period (Brinton 2009). The full-time salaryman model was not wholly abandoned during this period, but gaining such employment became increasingly tricky (Abegglen 2006; Mouer & Kawanishi 2005). The result was that freeters and other irregular workers came to represent Japan’s “new working class” toiling in service jobs with little stability or benefits on the bottom of the Japanese labor market (Slater 2010).

After the economic bubble burst, people began to refer to the 1990s as the so-called “age of self-responsibility” (Borovoy 2010; Gluck 2009). The poor and others on the margins were often seen as responsible for their poverty, which justified rolling back social programs designed to provide them with assistance. Individual versus collective responsibility for worker’s welfare remains a subject of considerable ongoing debate in Japan, as the current debates around how much government compensation freelancers deserve under the emergency declaration suggests. However, for some freeters, the sense of having their labor exploited while also being blamed for their hardships through arguments about “self-responsibility” provoked a political response through street demonstrations, and the organization of labor unions (see below).

|

The banner reads, “I’m sick of self-responsibility!!” ([jiko sekinin] moutakusanda!!) (「自己責任」もうたくさんだ!!); 2009 Mayday Demonstration; Miyashita Park, May 2009 (Photo by Robin O’Day). |

Freeter protesters positioned themselves as Japan’s version of the global precariat (Amamiya 2007, Standing 2011). Their protests leveraged sound, music, and culture to appeal to youth (Allison 2009; Hayashi and McKnight 2005; Mōri 2005; Obinger 2013; O’Day 2012). The protest culture freeters developed in the late 2000s influenced the massive anti-nuclear protests after the 3.11 disaster (Ogawa 2013; Manabe 2014; Brown 2018). While freeters did use social media to a limited extent during their protests, the development and proliferation of social media since the late 2000s has profoundly transformed political potentialities. Social media was at the center of political protests in the triple disaster in 2011 (Slater, Nishimura, & Kindstrand 2012), during student protests against the revision of the security treaties in 2015 (O’Day 2015; O’Day 2016. Slater et al. 2015; O’Day et al. 2018). Now we see freelancers leveraging their digital literacy for political gain during the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020.

From a broader perspective, the identification of freeter with the “precariat” cast a generation’s individualized search for self-realization through irregular work as a political movement against both exploitative capital shifts in Japan but also with links around the world. From that time, it is difficult to find any of the same sorts of politicization of precarious work (although there are some exceptions—like POSSE). SEALDs, who mounted many of the largest and most publicized movements since the 1970s, had difficulty finding a common cause or even ideological linkages to the growing number of precarious workers, let alone the labor movement in general. Some SEALDs members did participate in a campaign for a 1500 yen per hour minimum wage with the group Aequitas (Kyodo News 2017). However, the minimum wage demonstrations were much smaller in scale than those opposing constitutional revision. While it would be premature to suggest any movement-level shifts, in Japan as in other places, the COVID-19 economic contraction and the state’s seeming disregard for those in precarious work have generated some critique that goes beyond blogosphere griping.

Freelancers protest for more compensation.

Many freelancers were dismayed that the Japanese government offered them so little compensation relative to that provided to full-time workers. Even the procedures for claiming these benefits put out by the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry is dense, complicated, and bureaucratic (METI 2020). Freelancers have responded using their social media networks by researching and sharing strategies to maximize their entitlements despite the barriers. The “Furipara” website, powered by the Professional and Parallel Career & Freelance Association, serves as an information clearinghouse for benefits and compensation for freelance workers who have lost income with instructions on how to apply for the 4,100 JPY per person per day, and up to 200,000 yen in emergency loans for those who qualify (Furipara 2020).

Freelancers’ online collaborative efforts are becoming increasingly forceful in demanding that their benefits are increased and extended. Their political critique has become more pointed as the following tweet indicates:

|

This is not the first time the Abe Administration has been cold towards medium/small companies (chusho kigyo), sole proprietors (kojin jigyo nushi) and freelancers, etc. They have given us the cold shoulder for more than seven years. But the government has given tax breaks for large companies (daikigyo). This is the fundamental nature of the Liberal Democratic Party. So, we shouldn’t vote for the LDP and we need to vote (Twitter: @wanpakuten April 10, 2020). |

Some politicians from the ruling and opposition parties have also taken notice of the social media chatter and expressed support by tweeting about maintaining benefits for business owners and freelance workers. A member of the House of Councilors even posted videos directed at freelancers about how to apply for the current benefits they are eligible for (Twitter: @yamadataro43, May 4, 2020).

Freelance protests also erupted online, arguing to be recognized as victims of the state of emergency. Under Japan’s state of emergency declaration, governors only requested that people stay home and avoid going out at night because of the risk associated with going to bars and restaurants in spreading the virus (New York Times: 2020). Although not mandatory, the voluntary regulations to stay home devastated many restaurants, bars, and nightclubs. The hashtag, “#SaveOurLife” on Twitter, emerged from the “#SaveOurSpace” movement to bring awareness to the fact that music bars, live-houses, and nightclubs were going bankrupt from the voluntary regulations (SaveOurLife 2020a). The #SaveOurSpace movement articulated their grievance as follows:

We have witnessed that many petitions and voices are being heard by different categories of people suffering financially from the pandemic. We have noticed that it is not only laborers and businessmen but also many others who are suffering with no end in sight…We demand continuous support to protect our livelihood and work for people living in Japan” and demand that “Voluntary Regulations and Compensation must come in a set. (Twitter: @Save_Our_Space_, May 5, 2020)

In addition to the hashtag, “#SaveOurLife,” the hashtag, “#Protect Our Life and Work” (Inochi to shigoto wo mamorou), also began trending online. The “Protect our Life and Work” hashtag emphasized both the material losses (such as space, money, and jobs), in addition to drawing awareness to how livelihood and work are intertwined, and how the circulation of labor power is connected to the nation’s economy more broadly (Dommune 2020). One of the organizers of the movement, Miru Shinoda, explained the meaning behind the hashtag as follows:

The life of people living in this country, this society, are under threat, including freelance, irregular laborers, foreign laborers, homeless, sex workers, social workers, and medical professionals. While the city is silent under the emergency declaration, sad voices are echoing through this society at the same time (Save OurSpace 2020a).

Critiquing the “Stay Home” campaign in major Japanese cities, the group argues that the regulation has caused the loss of many jobs. At their press conference, they included a bar, club and cinema owners, theatrical company organizers, nursery teachers, and others to share their stories about job losses due to the emergency declaration (SaveOurSpace 2020b). They also invited politicians from both the ruling and opposing parties to share their plans for increasing benefits. Using social media to promote their activities, petitions, and press conferences one politician from the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), Hiroshi Ando, actually joined their press conference to announce that he would work towards advocating for freelancers (SaveOurSpace 2020c).

It is unusual for a member of the ruling party to join an online political protest. Part of the credit must go to the freelancers themselves in their ability to rapidly organize and gain enough public visibility to make politicians take notice. Another aspect of this may also speak to how pervasive fragmented labor has become in Japan. Although freeter protests for fair treatment remained mostly on the political fringes, where mainstream politicians mainly ignored their demands, there may be a sense among some Japanese politicians that the rising numbers of freelancers will ultimately matter at the ballot box. Why otherwise would they appear to support these protests?

Conclusion

The Covid-19 pandemic caught many freelance workers off-guard by quickly and dramatically exposing their vulnerabilities in the Japanese labor market. Under the Abe administration’s leadership, freelance work has expanded rapidly under the promise of labor reform. Almost everyone agrees that Japanese corporate culture and workplaces need reform. Still, it is becoming increasingly hard to see how the drive to maneuver higher numbers of workers, especially the younger ones, into irregular forms of employment benefits anyone except businesses and governments who can argue that they are no longer responsible for these workers’ welfare when times get tough. The message was read by many that a freelancers’ labor is less valuable than a full-time worker’s labor. The lower levels of compensation offered under the emergency declaration, situated freelancers as not only less valuable workers but also less entitled to the full benefits available to all citizens. This sparked an outpouring of anger and disbelief on social media platforms. Freelance work has become ubiquitous for many workers that some found it hard to believe that they belonged to a structurally marginalized group. Freelancers have moved faster, in large part due to their digital literacy, in organizing and demanding better treatment than other marginalized workers–most notably in contrast to freeters in the early 2000s. Freelancers have publicly demanded more, and as a growing segment of the workforce, they might get it through organized online protests in ways that street protests never fully delivered for freeters.

Bibliography

Abegglen, James C. 2006. 21st-Century Japanese Management: New Systems, Lasting Values. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire; New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Abema TV. 2020. Arguing against daily wage 4100 JPY. “Freelance and Office workers” Why the gap for paid compensation for school closure? People on the verge under Corona. (日給4100円に反論”フリーランスと会社員”休校補償になぜ格差? コロナで追い込まれる人たち). April 21.

Allison, Anne. 2009. The Cool Brand, Affective Activism and Japanese Youth. Theory, Culture & Society 26(2-3):89-11.

Amamiya, Karin. 2007. Precariats: The Unstable Way of Life of the Digital Day Labouring Generation (プレカリアート―デジタル日雇い世代の不安な生き方). Tokyo: Yosensha.

Asahi Shimbun. 2020a. “Subsidy for parental leave, 8330 yen per day upper limit. Not applicable for self-employed.” (保護者休業の助成金、1日8330円上限 自営は対象外) March 3.

Asahi Shimbun 2020b. “More policy aid needed for those feeling the pinch of the virus.” March 13.

Brinton, Mary. 2011. Lost in Transition: Youth, Work, and Instability in Japan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brown, Alexander. 2018. Anti-Nuclear Protest in Post-Fukushima Tokyo: Power Struggles. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

Borovoy, Amy. 2010. “Japan as mirror: Neoliberalism’s promise and costs.” Ethnographies of Neoliberalism. edited by Carol J. Greenhouse, 60-74. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

CNN 2020. “Japan is offering sex workers financial aid. But they say it’s not enough to survive the coronavirus pandemic.” April 20.

Council for the Realization of Work Style Reform. 2017. “The Action Plan for the Realization of Work Style Reform.” March 28.

Crowdworks. 2020. “About 70% of Freelancers have lost income due to the spread of new coronavirus. Emergency national survey conducted on 1,400 freelancers-Proposal: Cash payment to wider range of freelancers” (新型コロナウイルス感染拡大の影響により、収入が減ったフリーランスは約7割 1,400人のフリーランスに対し緊急全国調査を実施 ~提言:幅広い層のフリーランスへの現金給付を~). April 6.

Deutsche Welle. 2020. “Japan’s freelancers go rogue, shun salaryman tradition.” March 3.

Dommune. 2020. “SUPER DOMMUNE 2020/05/07 ‘#SaveOurLife’”. YouTube Video. 4:38:55, May 10, 2020.

Freelance Association. 2018. Professional working style: Freelance White Paper 2018 (プロフェッショナルな働き方・フリーランス白書 2018).

Furipara. 2020. “Furipara Freelance and Parallel Careers: To all sole proprietors who were influenced by Corona.” April 25.

Gluck, Carol. 2009. Sekinin/Responsibility in Modern Japan. In Words in Motion: Towards a Global Lexicon. Carol Gluck and Anna Tsing, ed. Pp. 83-106. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Hayashi, Sharon, and Anne McKnight. 2005. “Good-Bye Kitty, Hello War: The Tactics of Spectacle and New Youth Movements in Urban Japan.” Positions 12(1):87-113.

Honda, Yuki. 2005. Freeters: Young Atypical Workers in Japan. Japan Labour Review 2(3):5-25.

Intloop. 2020. “Survey on the effects of new coronavirus on freelance.” (新型コロナウイルスのフリーランスへの影響 実態調査を実施). April 6.

Japan Times, 2020. “Coronavirus might cost Japan over 1 million jobs, economists say.” May 14.

Japan Times. 2017. “Can Japan, land of lifetime employment, handle the rise of freelancers?” May 15.

Kyodo News. 2017. “Young people mount campaign to raise minimum wage, end poverty in Japan.” June 11, 2017.

Lancers. 2018a. 2018 Freelance Survey (フリーランス実態調査 2018年版を発表). April 4.

Lancers. 2018b. “Evolving Future of Freelance: Freelance Fact Finding 2018.” (進化するフリーランスの未来ーフリーランス実態調査2018ー).

Mainichi 2020. “Japan’s exclusion of adult entertainment workers from public aid blasted as discrimination.” April 3, 2020.

Manabe, Noriko. 2014. “Uprising: Music, youth, and protest against the policies of the Abe Shinzō government“, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 12, Issue 32, No. 3, August 11.

METI (Ministry of Economics, Trade, and Industry). 2020. “Accepting consultation on financial support and sustainable benefits for small and medium-sized businesses affected by the new coronavirus infection” (新型コロナウイルス感染症により影響を受ける中小・小規模事業者等を対象に資金繰り支援及び持続化給付金に関する相談を受け付けます).

METI (Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare). 2018. Working Professionally, Freelance White Paper (プロフェッショナルな働き方・フリーランス白書 2018).

METI (Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare). 1992. White Paper on Labour-1991. (労働白書平成3).

Mōri, Yoshitaka. 2005. Culture = Politics: The Emergence of New Cultural Forms of Protest in the Age of Freeter. Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 6(1):17-29.

Mouer, Ross E., and Hirosuke Kawanishi. 2005. A Sociology of Work in Japan. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press.

News Week. 2020. “Unemployment rate was 2.6% in April, the highest level in 2 years and 4 months” (完全失業率4月は2.6%、2年4カ月ぶり高水準 コロナで休業者過去最高). May 29.

New York Times. 2020. “Japan Declared a Coronavirus Emergency. Is It Too Late?” April 7.

Nikkei. 2020. “6 million workers on leave in Japan as coronavirus takes toll.” May 30.

Obinger, Julia. 2013. Amateurs’ Riot! Alternative Lifestyles as Activism in Urban Spaces of Japan (Aufstand der Amateure! Alternative Lebensstile als Aktivismus in urbanen Räumen Japans). PhD Dissertation. University of Zurich.

O’Day, Robin, 2016. “Student Protests Return to Tokyo.” In Anthropology News, American Anthropological Association. Volume 57: Issue 1-2: 11-12.

O’Day, Robin, 2015. “Differentiating SEALDs from Freeters and Precariats: The politics of youth movements in contemporary Japan“, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 13, Issue 37, No. 2, September 14.

O’Day, Robin. 2012. Japanese irregular workers in protest: freeters, precarity and the re-articulation of class. PhD Dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of British Columbia.

O’Day, Robin; Slater, David H.; and Satsuki Uno, 2018. “Mass Media Representations of Youth Social Movements in Japan.” Social Movements and Political Activism in Contemporary Japan: Re-emerging from Invisibility. edited by David Chiavacchi and Julia Obinger, Social Movements, Protest, and Culture Series. London and New York: Routledge. Pp. 177-197.

Ogawa, Akihiro. 2013. “Young precariat at the forefront: anti-nuclear rallies in post-Fukushima Japan.” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 14 (2), 317-326.

Ozy, 2019. “As Japan’s Work Culture Changes, Freelancers Bear the Brunt of Abuse.” December 17.

POSSE. 2020. NPO Posse.

Reuters. 2020. “Japan’s March jobless rate rises to one-year high as coronavirus hits economy.” April 28.

SaveOurSpace. 2020a. “#SaveOurLife.” Lastly modified May 22, 2020.

SaveOurSpace. 2020b. “#SaveOurLife Press Conference – Miru Shinoda (Musician/SaveOurSpace) Summary of the Press Conference” (#SaveOurLife 記者会見より ー 篠田ミル(音楽家 /SaveOurSpace) 会見趣旨). May 18.

SaveOurSpace. 2020c. “#SaveOurLife Press Conference – Hiroshi Ando, member of the House of Representatives (LDP)” (#SaveOurLife 記者会見より ー 安藤裕 衆議院議(自民党). May 16.

Sekitova 2020. “Recent report after April 6th.” (4月6日以降の近況報告). Note. April 20.

Slater, David H. 2010a. The Making of Japan’s New Working Class: “Freeters” and the Progression From Middle School to Labor Market. The Asia-Pacific Journal, 1-1-10, January 4th.

Slater, David H.; Nishimura, Keiko; and Love Kindstrand, 2012. “Social Media, Information, and Political Activism in Japan’s 3.11 Crisis,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol 10, Issue 24, No 1, June 11, 2012.

Slater, David H.; O’Day, Robin; Uno, Satsuki; Kindstrand, Love; and Chiharu Takano, 2015. “SEALDs (Students Emergency Action for Liberal Democracy): Research Note on Contemporary Youth Politics in Japan“, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 13, Issue 37, No. 1, September 14.

Standing, Guy. 2011. The Precariat: The New Dangerous Class. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Takahashi, Kanako. 2020. “Losing income from Corona! Freelance Editor’s now and the future” (コロナで収入激減!フリーランス編集者の今とこれから). Mi-Mollet. April 11.

The Atlantic. 2018. “Are Japan’s Part-Time Employees Working Themselves to Death?” August 8.

Twitter: @chiechie5132002, ¥4,100 per day. What? #Cry of Freelance. (日額¥4,100ては?#フリーランス悲鳴). March 10, 2020.

Twitter:@konno_haruki. April 21, 2020. “In today’s Abema TV program…” (今日のアベマTV…).

Twitter: Twitter:@ponpoko_Reverse. March 5, 2020. “Some say that we should have known that becoming freelancers would ultimately depend on our self-responsibility…” (救済なしの自己責任を承知でなったんだろ…).

Twitter: @Save_Our_Space, May 5, 2020. “Notice of Press Conference” (記者会見のお知らせ).

Twitter: @taiyaki3150, March 5, 2020. “I’m well aware but I chose to be freelance.” (百も承知でフリーランスを選んだ.)

Twitter: @wanpakuten, April 11, 2020. “This is not the first time the Abe Administration has been cold…” (安倍政権が中小企業、個人事業主、フリーランス等に冷淡なのは今に始まったことではないよ).

Twitter: @yamadataro43, May 4, 2020. “How to apply for maintained benefits up to two million yen” (【第四弾】中小企業・個人事業主・フリーランスの方必見。最大200万円持続化給付金!申請方法給付金額等ご説明します).

Twitter:@yoppymodel, March 18, 2020. “There are theories hanging around saying that ‘Freelances are self-responsible,’” (「フリーランスは自己責任だろ」みたいな論がありますけど).

Washington Post. 2020. “Work from Home, they said. In Japan, it’s not so easy.” April 6.

Yahoo News 2020a. “Despite corona, is having a good reputation worth going to work?” コロナでも「出勤すれは好評価」でいいのか? 日本社会の深すぎる闇. April 22.

Yahoo News 2020b. “The voice of ‘self-responsibility’ for freelancers suffering from corona shock.” (コロナショックで苦境に立たされるフリーランスに“自己責任”の声…安心して選択できる働き方にするためには?). April 23.

Uno, Satsuki. 2017. “The Cost of Starting-Up: The Field Study of Innovation of “work” by Student Start-Ups in Tokyo.” M.A. Thesis. Graduate School of Interdisciplinary Information Studies Information, Technology, and Society in Asia, University of Tokyo.

Zoho. 2020. “The Big Gig: Japan, the land of the rising gig economy.” February 26.