Abstract: In the context of the global increase in displaced people, spiking to nearly 80 million in these corona times, Japan has also seen a dramatic increase in the number of applications for refugee asylum since 2010. Despite increasing numbers of applications, Japan has not increased its refugee recognition rate. Unable to return home to sure persecution when rejected, many refugees end up in Japanese detention centers once their visa expires. Like jails, hospitals and detention centers everywhere, detention centers in Japan are crowded and dangerous and unable to protect the detainees inside. Japan has been slower than many other countries to take precautions, including temporary release. This paper outlines some of the policy shifts that have led to this dangerous situation, the conditions of anxiety inside the detention centers themselves in Tokyo and Ibaraki and the problematic situation of “provisional release” of some detainees into a corona-infested Japan without any safety net or protection. We hope to not only point out the immediate danger of infection under COVID-19, but also the larger dynamic of using detention to manage a refugee asylum system that has proven to be ineffective and unjust.

Key words: COVID-19, vulnerable populations, refugees, detention center

Infected detainment

The bitter irony of dying of COVID-19 in the “Shinagawa Detention Center” is not lost on the many refugee asylum seekers who have been detained there.1 Patrick, a Cameroonian man, was a labor activist with scars over his whole upper body from torture. He escaped two years ago from his home country and fled to Japan; like so many others, he is still awaiting the results of his refugee hearing. He is a brave and proud man but in detention, he has been reduced to desperation.

The Tokyo Regional Immigration Bureau (東京出入国在留管理局), commonly called “Shinagawa Immigration” by most asylum seekers, is one of 17 such offices in Japan, a place that most foreigners living in Kanto have been to at some point. Now, they have some of the longest lines since the 2011 earthquake, snaking out of the building around the corner. They are practicing social distancing, so they limit how many people can enter at once. But if you take the elevator up to the 7th floor, you will find another world, one where there’s no chance of social distancing, one where the frustration and exhaustion we have all been feeling with the COVID-19 crisis has been replaced by fear and panic, the detention facility. Just as jails that house criminals, detention centers around the world housing refugee asylum seekers and others guilty of nothing more than visa infractions, are experiencing mass infection. Wherever we see forced detention, we are witness to conditions that are sparking calls from activists who point out the gross and unnecessary human rights violations because of the failure of the detention centers to protect detainees from infection (International Detention Coalition, 2020). Even poplar media sources are sounding the alarm. In April, The Washington Post (Lang, 2020) pointed out the potential danger in the US, calling the facilities a “time bomb” (10), a tragedy waiting to happen. The Guardian (Levin, 2020) calls detention facilities in the UK “death traps.” So dangerous are the conditions inside the detention centers that even facilities run by the ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement), well-known for its zealous, even brutal methods, have begun releasing hundreds of detained immigrants throughout the US (Katz, 2020b). Japan is not immune. More than 10 infections had already been reported at correctional facilities in Japan as early as April 21 (Osumi, 2020). One detainee responded when he heard about the situation in the U.S.: “So Japanese Immigration is actually worse than the ICE in America? That is pretty bad.”

Unlike some other populations that have become particularly vulnerable in the age of COVID-19, those in the detention centers are deliberately collected under conditions that are known throughout the world to be dangerous, and even deadly. They have been put at risk not as an unintended consequence or even heartless neglect but through a progressively more punitive policy of using prolonged periods of detention to criminalize asylum seekers who come to Japan fleeing persecution in their home countries. This practice has a long history in Japan (Global Detention Project, 2013). Today, there are more asylum seekers in the different detention centers in Japan than ever before, producing the sort of crowded conditions inside that makes any serious preventative action meaningless; in these enclosed contexts, more hand sanitizer or masks have not, indeed, cannot, prevent infection if a virus such as COVID-19 penetrates its walls.

In an effort to explain how these dangerous conditions came about, this paper outlines some of the policy shifts that have led to this situation, the conditions of anxiety inside the detention centers themselves in Tokyo and Ibaraki, and the problematic situation of “provisional release” (Immigration Services Agency of Japan, n.d.-a) of some detainees into a corona-infested Japan without any safety net or protection. We hope to not only point out the immediate danger of infection under COVID-19 inside the detention centers, but also the larger dynamic of using detention to manage a refugee asylum system that has proven to be ineffective and unjust.

The refugee contacts for this paper were established at the Shinagawa Detention Center through the Sophia Refugee Support Group whose members have been visiting the detainees 4-5 times per week for the past two years. As fears of infection grew in 2020, regular visits were canceled, and the authors visited as individuals. In addition, Babaran made regular visits to the detention center at Ibaraki until visitations were closed there also. After that, interviews were conducted by telephone. As some detainees were released, we resumed interviews, both face to face and by telephone. (See Barbaran & Slater 2020).

Refugees coming to Japan2

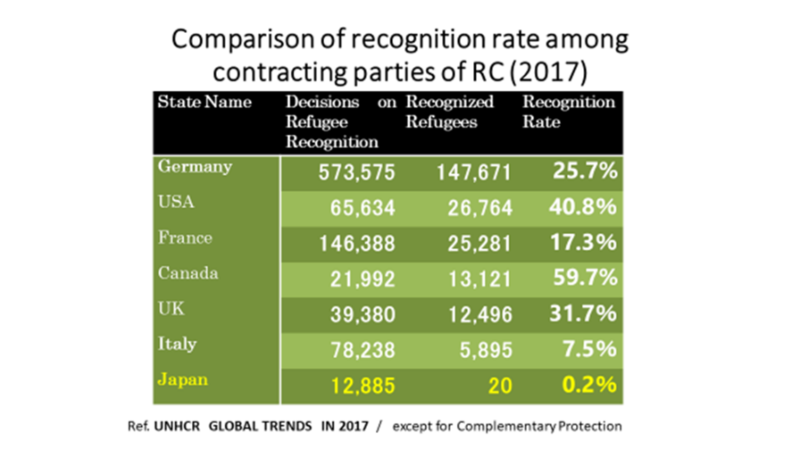

While Japan has a regulatory procedure for refugee recognition (Immigration Services Agency of Japan, n.d.-b; UNHCR, n.d.), it has not been welcoming to refugee asylum seekers.3 Since 2010 and the explosion of the global refugee crisis, there was a steady increase in the number of asylum applicants into Japan, as in many other counties around the world. They flee persecution, usually in their home countries and seek asylum elsewhere, hoping to be recognized with refugee status as outlined in the 1951 Refugee Convention (UNHCR, 2020). While there were only 12,020 asylum applicants in 2010 to Japan, by 2017, the number of asylum applications rose to 19,628. Rather than opening its doors to this new flow, Japan responded by accepting a smaller percentage. Japan is so out of step with most of the other larger economies around the world that the numbers almost defy comprehension. In 2017, there were a total of 12,885 applications processed but only 20 applicants were recognized as refugees. This is an acceptance ratio of less than 0.2%. In comparison, in 2017 Germany recognized 147,671 out of 573,575 cases for a rate of 25.7%; Canada accepted 13,121 out of 21,992 applications processed for a rate of 59.7%.4 This despite the fact that both of these countries have smaller economies and smaller populations than does Japan—two metrics often used to evaluate a county’s capacity to accept refugees (UNHCR, 2002). In fact, using these metrics, Oxfam (2016) estimated that had Japan taken their “fair share” of Syrian refugees, it would be reached almost 50,000—just of Syrians—a year when Japan recognized 28 refugees in total.

In part as a response to the increase in those applying for refugee status, and on the assumption that among those applications there were many who were abusing the application system (濫用・誤用的な難民認定申請) the Ministry of Justice passed two sets of resolutions, one in 2015 (Ministry of Justice, 2015) (see here for summary chart), which was revised in 2018 (Ministry of Justice, 2018) (summary chart). Under the new system, MOJ began sorting applications into 4 preliminary categories, based on prima facie changes of approval. Thus, Tanaka (2018) in the Japan Times wrote that the new system was designed to “identify those who are genuinely in need of protection and discouraging those who don’t from applying”.7 For those who are initially sorted into the likely pile, those they sometime called real or “true refugees” (真の難民),this new system is supposed to facilitate the fast tracking of refugee recognition. This new system was also designed to allow immigration officials to identify those they often refer to as “so called fake refugees” (いわゆる偽装難民).5 Tanaka concludes that the official view is that this policy was working as designed based on the fact that the number of withdrawn applications increased, and the number total applications plummeted to almost half the following year.

Yet, even at the time of proposal, the claim of fast-tracking was perplexing because the criteria of recognition had not changed, and thus there was little reason to imagine that this new procedure would result in any higher rates of refugees being recognized. And in fact, it did not. In 2018 there were 48 applications gaining recognition status, and then back down to 44 in 2019, a small fluctuation that has never raised the acceptance ratio above 1%. If the goal was to increase the number of acceptance of refugees, this policy has been a failure.

The second stated goal of this truncated preliminary sorting was to better differentiate real from “fake” refugees.6 In this case, the policy seems to be a failure not only in execution and result, but also in design. While, this new procedure might be expeditious for the Immigration officers, it provides insufficient time to allow almost any refugee to gather the materials necessary to support their persecution claim—a file that ends up containing hundreds of documents. As is often pointed out, when a refugee flees danger, they do not have time to get a police report (a document much favored by immigration officials the world over, including Japan). This is especially true when it is the police who are the agents of persecution, as is characteristic in circumstances of own-state persecution. This shortened time frame is also probably a violation of the 1951 Refugee Convention, a document Japan signed in 1981, ensuring the rights of all asylum applications to a full and timely review of their application. As such, the procedures are ineffective, at least insofar as their ability to distinguish between real and “fake” refugees because there is no chance to document these differences through a review of applications. For many, it is worse. As one Iranian refugee explained to us, “it does the exact opposite of what they say” it is supposed to do because the only applicants “who could possibly show up with full documentation are surely fake.” He continues, on the other hand, “for people like me, people who are escaping [from persecution] cannot get documents as they flee the country.” So, he continues, “Japan is actually punishing the real refugees.”

Just as troubling as the decision process is the treatment of those rejected in their application—which is more than 99% of all applicants. While some applications are supposed to be fast-tracked, those applications that did not have sufficient documentation from the start can be taken out of the review process. At that point, their application process is over, and, as noted by Tanaka (2018), applications that do not “fall under the definition for refugee status now face immediate deportation” (para 15). For a fuller explanation of the whole deportation procedure see Immigration Services of Japan, n.d.-c). Deportation back to one’s home country means for most refugees that they are being returned to the situation that is the source of danger and often even death. This surely is a violation of one of the core principles of the Convention, that of “non-refoulement”, or the prohibition against returning any asylum applicant to their country of persecution (UNHCR, 2007). For many refugees, and especially those facing the deadliest threats, this is exactly what the Japanese government is doing in deportation procedures. Patrick explains the prospect of being returned to Cameroon, “I have to be deported, they say. But if I have to return to Cameroon, I’ll be killed. I will be killed before I get out of the airport in Douala.”

The whole system is difficult to understand from the point of view of a refugee asylum seeker. As one African man who has been in detention for more than 2 years, asked,

Another refugee who is still awaiting an appeal explains his situation in this way. “Japan is such a safe and orderly country. They have made it so beautiful. I love being here. In fact, many Japanese have been very kind to me. But now the government wants to send me back where it is so dangerous. Can they hate me so much? But why? Just because I am a refugee?”

Those who refuse a deportation order are put into detention.

Entering the Detention Centers

There are many ways to get put into the detention center but committing a crime as outlined by Japanese law is not one of them. A refugee who commits a crime is put in prison, not the detention center, just like any Japanese. The detention centers are for those who violate the conditions of their visa. For some, this occurs when immigration turns down their refugee asylum application, in which case they are in violation if they have no other visa. Many others do not get that far, as they never get a chance to file an application before they are detained because the immigration official’s refusal to accept the application. (Note, the acceptance of an application is different from the eventual recognition of an asylum claim. The acceptance of the claim enables the whole refugee recognition process to begin. If an immigration official refuses to accept the application itself, then there is no possibility of an evaluation of the refugee’s case.) Many of the refugee asylum seekers have been placed in the detention center upon their arrival into Japan, directly from the airport, if they are deemed by the immigration official to lack sufficient document to even apply for asylum. (We have never been able to ascertain exactly what counts as enough or proper materials to allow the acceptance of an application as the situation of those who are put into detention in this way are wildly various.)

The refusal to even accept an application is a rather dramatic departure from the practice around the world, where usually self-declaration of refugee status and an expressed desire to seek asylum begins the process of asylum review. But as Sarah from Nigeria explains, it does not always happen that way at Narita. In her case, the “immigration official at the airport decided I did not have the right paperwork [to apply for asylum], even though I told him I was a refugee. And I did not have any visa o stay in Japan.” She was brought directly to the detention center in Shinagawa (separated from her child who was put in a separate care facility). As the procedures have grown more stringent over the last few years for those who are in Japan, awaiting the outcome of their asylum application, an increasingly large percentage end up in a detention center due to some small infraction in their regular renewal process, a missed deadline or failure to report a change of address.

Once inside the detention center, some detainees re-think their choices. (This is not usually the case with refugee asylum seekers who cannot return home but applies to others in the detention center who have simply overstayed their visa). The treatment at the detention centers can be quite extreme. “This place is just a prison,” explains one Syrian. “They try to kill you with bad food and let you die with too many medicines.” If the detainees think they can find some way to return to their home country, it is possible to repatriate— “self-deport,” as is sometimes said. But this process is undertaken at their own expense; they pay for the flight, and usually, must pay a bond of between 100,000 to 300,000 yen. Moreover, they usually also need to find and hire a lawyer to file the paperwork. For the vast number of those in detention, unable to work to get money and isolated from any support network that might help to raise this money, this is not possible. Most refugees inside the detention center are also looking for some support such as a lawyer they can afford, often not to return home but in order to appeal a failed application result. Under the COVID-19 conditions, even if detainees want to find a way to leave Japan that is not possible due to the travel restrictions.

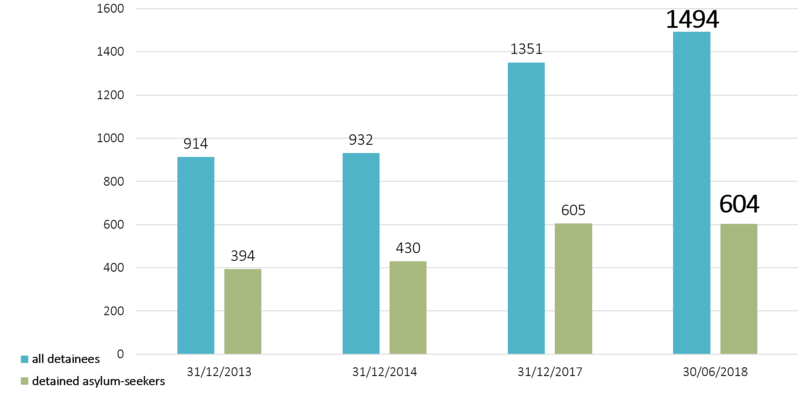

The predictable result is an increase in the number of people who are sent into the detention center. Here is a chart that shows the steady increase in the use of detention as a way to address these issues.

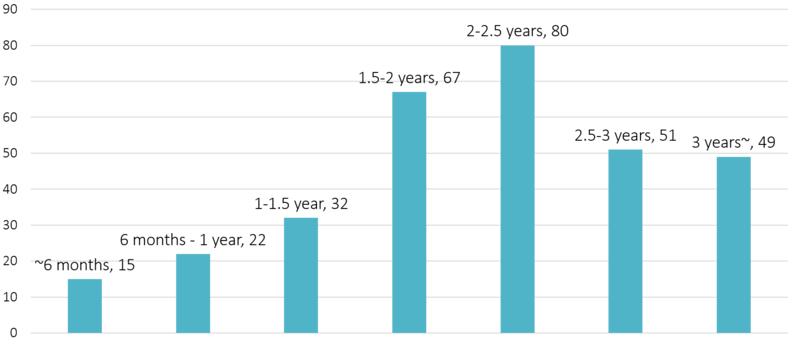

The crowded conditions of so many people being placed in detention centers each year is compounded by the fact that the length of detention is increasing. Here is a chart that shows the number of detainees and how long they have been detained at the detention facility in Ibaraki.

Note that these numbers do not include the length of detention before the detainees receive deportation orders (60 days max.) Also, they do not indicate the final or stipulated length of sentencing. Unlike many other countries, and even unlike the situation for many criminals who are incarcerated in Japan, those in the detention center are not given any period of sentencing when they enter. They never know how long they will be forced to stay there. Most of them only know that the length of time is increasing. Thus, these figures are not the actual length of detention that any detainee will end up serving. These figures represent the length of time served so far of those people who are currently incarcerated.

While there have been calls from international watchdog groups (Human Rights Now, 2019; Human Rights Now, 2020), advocacy groups (The Japan Times, 2019; Mainichi Japan, 2020b) as well as calls in the Japanese popular press (Mainichi Japan, 2019a; Mainichi Japan, 2019b), these periods of “indefinite detention” themselves represent a human rights violation. In effect, Japan is using detention not as a temporary location until a trial or repatriation become possible, but as a punitive measure, to punish already persecuted refugees for the mistake of seeking asylum in Japan.7 It also serves as a preemptive measure to discourage others from coming. Even in the best of times, Japanese detention policy involves profound human rights issues for the length of time and treatment of detainees; in the age of COVID-19, it is immediately life threatening for many people within the detention center.

Fear of Closed Spaces

Inside the detention center, proper safety measures, even if followed, are not enough to keep detainees safe. To be detained is to be unable to move about, and when so many others are detained in a narrow and enclosed space, infection spreads easily. The danger at the Shinagawa Detention Center is apparent just from looking at the layout. There are two room sizes, one for 4 people and one for 8, with as few as only 2 tatami mats per person in each room.

From late afternoon until morning, the detainees are locked in their rooms in these particularly close conditions. As one woman from Uganda explained, there is “not enough space to even walk around. When you lie down you are next to at least two other people. It is like living in a sack.” Someone joked, “we are breaking Koike-san’s rules (Tokyo Metropolitan Government, 2020) all night long.” One man explained that “when you cough or sneeze, the germs are in the dead air. It never circulates. It just falls on you. The windows are always closed—many of them do not even open at all. We’re all trapped inside here, and we can’t breathe.” He added, “and you know where it strikes—in the lungs.” But even when they are allowed out of their rooms into the shared spaces of the block, it is not much better. One detainee, pointing to the counters and the food, said, “everything you touch, you have to think, is it safe? Can I touch the door handle, can I sit on the sofa? Will this infect me?” He pointed out, “this is a captive population, and if COVID-19 gets in, it will spread like wildfire.” Patrick explained, “in the final analysis, if anyone got sick, the whole block would go down. Probably the whole Detention Center.”

If the seal around the detention center were tight, at least that would provide some security. But in fact, as we are told repeatedly, there is a steady flow of people coming in from outside—not only guards and service personnel, but also new detainees. As one detainee who has been inside for 3 years now explained, “if we cannot get out, at least we need to make sure that those who come inside are healthy.” In late March, after seeing what was happening around the world on TV, a group of detainees called for a meeting with the head guard, requesting that no other detainees be transferred in, or if they were still allowed in, they should at least be quarantined for two weeks. “It was not a strike or anything like that—we just wanted to talk.” While the guard sounded sympathetic, the flow of people, including new detainees, continued until Prime Minister Abe’s emergency declaration on April 6. After that, visitation rights were suspended, but the service people and even some new detainees were still trafficking in and out.

Testing is a subject that many detainees talk about. A detainee from Peru noted that testing is probably impossible for most of those inside: “None of us have health insurance, they don’t give us health insurance, and there is no way we can pay for the test.” One older man who asked that his home country not be mentioned, “just say, Middle East,” is similarly pessimistic. He explains, “some of the younger ‘hot heads’ think that if you protest, you can change things. That is crazy. We usually cannot change anything, at least not in normal times.” But this time, with this threat of COVID-19, even he thought things would be different. He said, “I understand that Japan cannot test everyone, and maybe those who are not sick do not need to be tested IF they are outside … But if they come inside the Detention Center, it is different. They could be carriers or almost sick or anything—you do not know for at least two weeks, right? If that virus gets inside, we cannot get it out, and we cannot live with it. We cannot isolate ourselves or practice safe living inside.” He slumped down in his chair in the visitor’s room, with nothing more to say.

Dangerous Information

During this crisis, we are all struggling to get the right information in time to make the right choices, but detainees are given almost no information. They have no access to computers or phones. Ishikawa Eri, board chair of the Japan Association for Refugees, says the information that is provided is inadequate both inside and outside (Tamura, 2020). “Not knowing what is happening makes you crazy and terrified because you don’t know what to believe,” says Paul, who has been in detention for a few months after his refugee application was rejected and he could not afford a lawyer to appeal.

Unsurprisingly, in this context, rumors circulate faster than the virus. . One day in March, we were told that there are already 2 confirmed cases of COVID-19, the next day they said 12 cases, the day after, zero cases. When you are desperate for any information, you grasp at anything, and when you have no way to confirm its truth, you do not know what to believe. Often detainees end up playing a guessing game, trying to figure out what is happening from observing any changes in routine or procedure. Mac is a Congolese asylum seeker who married a Japanese woman and has a child. She divorced him, leaving him without a valid visa, and he was put into detention. He is now awaiting a court order to allow him to see his child. He says he has noticed detainees being moved around the facility. “They are moving many people around, out of some blocks into others,” an observation we have heard from many detainees, both male and female. “We know that the place is maxed out, so crowded that every bed is full,” the man added. “This is because there was a confirmed case of coronavirus in another block.” I asked how he knew this. “I can just tell. They tell us nothing but why else would they do this, making our situation even worse by overcrowding.” These statements could be true—they made sense. But there was no official word from the guards or from the Immigration office, which made everyone even more anxious. One man, now out of the detention center and living with his Japanese wife in Tokyo, explains: “This is part of the psychological torture that they put you through. It is not that they do not think of you, just ignore you. They know. They plan it. They know that without any clear information, you cannot know. It is one way that they control you inside—through your mind.”

Incomplete Precautions

If no information is dangerous, a little information can be worse, especially when the guidelines that detainees do come across are immediately contradicted by the routines they have to follow inside. One shy and soft-spoken woman we spoke to inside the detention center explained, “Everything we come to know is from NHK.” There is a TV that is always on in the common room. “We cannot understand much” because it in in Japanese, she says, “but we watch the diagrams—about being 6 feet apart, always using hand sanitizer, wearing masks, all that. We look around here and see that these are all things we cannot do ourselves inside.” When this discrepancy is brought up to the guards, they are unimpressed.

The efforts to follow some guidelines are inconsistent and often end without any effect. Social distancing is not possible when you are living in a room with 7 other people and no partitions. Personal hygiene in such institutional settings is compromised at best. For the men, it seems that the guards have begun giving more masks if asked often enough. As a rule, the women get one mask per week. Another woman who was taken directly to the Detention Center upon declaring her refugee status at Narita Airport explained, “but the masks get dirty so almost no one wears them inside. Some of the detainees do not know that masks are important—and some do not care, saying we will all die anyway.” Then she whispers, “Some think the whole [corona] thing is fake, just a way to frighten us.” Finally, she adds, “The guards do not enforce any masks for us—but they all wear masks.”

There is one moment of mask enforcement: if detainees do not wear their mask, they cannot meet outside visitors in the visitation room (menkai shitsu). The detainee we spoke with does not know the reason for this rule, but it is odd. “I guess you can’t get any germs with that thick glass between us,” she said. “Maybe it’s just so outsiders think we are being protected…I don’t know.” Indeed, there is a 6 cm acrylic barrier. Detainees cannot get any wipes or hand sanitizer—no products with alcohol are allowed inside. If you get sick, you can take your own temperature. As one detainee from the Philippines noted, “when someone gets sick, no one does anything. We get some pain relievers, but that is only worse, because then it masks any symptoms.” That the general health care is deficient in the detention centers has long been documented Mainichi 2019) and many detainees are in varying states of ill health. As more about COVID-19 becomes known, it is clear that generally poor health and lingering illness are important pre-existing conditions that put people inside detention centers at added risk.

While the immigration bureau does not release any information on the procedures that it follows to protect detainees form COVID-19, advocacy group Ushiku no Kai reported a government official at the Eastern Japanese Immigration office in Ushiku, Ibaraki Prefecture, as saying that doctors give shinsatsu (medical examinations) to those suspected of having COVID-19. Of course, if a detainee tests positive while inside detention, it probably means that he was infested by another detainee and/or has already infected others. Neither Immigration officials nor the Department of Justice makes this data readily available.

Release

As the threat of infections grew, many called for the release of detainees (Osumi, 2020). Komai Chie, a registered attorney with the Tokyo Bar Association and former chairperson of the Foreign Human Rights Committee for the Kanto Bar Association, makes the case for release as the only humane option. “At this moment, detainees are at great risk of infection and many have made a plea for release just to save their own lives,” she says, adding that while some have been released, “the number is not enough and the risk is growing day by day.” She is not alone in her thinking. Both Amnesty International Japan and the Japan Association for Refugees have called for the release of as many of those held in detention centers as possible due to circumstances surrounding COVID-19. (It was not until August 7th that the Immigration admitted that anyone had been infected at Shinagawa—1 detainee and 4 employees at the facility (Ida 2020).)

On May 1, the Immigration Services Agency announced it would begin to allow “provisional release” and a two-week quarantine of some detainees under restricted circumstances, though there was no acknowledgement of how many would be released (The Japan Times, 2020). According to the detainees we spoke to it appears that 50 were released from each Ibaraki and Shinagawa almost at once, with no warning and no support, and thus no way for the detainees to prepare at all

The news of release was greeted with great enthusiasm among the refugee support community of lawyers, advocates, and supporters, even with the restrictions imposed. Despite the emergency status, those released were still expected to post bond and were subject to limited movement. Priority was given to those seeking medical treatment although there was no notice that any of the detainees had tested positive to the virus. (This could also be because none of the detainees we spoke to either inside or outside after release had been tested. Also see The Japan Times, 2020b). In the words of one detainee, the sudden provisional release “this was basically an admission that they could not keep us safe inside. It was also a way to avoid having anyone die while they were inside.” That is clearly true—no detention center wants to be responsible for the death of detainees, least of all if that death could have been so easily predicted by events abroad. . In this way, detention centers in Japan are not different from any others around the world. There is, in fact, no way to keep anyone in captivity—detention, imprisonment, or hospital—safe in the face of a viral outbreak. Yet, at the same time, it was also a strategy that the detention centers in Japan have used in the past to avoid responsibility for sickness and deaths during the different hunger strikes that have recurred during past decades (The Japan Times, 2014). When a hunger striker gets so weak that they are close to death, rather than negotiate some resolution to the grievance, they are usually “provisionally” released (Fritz, 2019). Release can last a few weeks, until they regain some of their health, and then they are re-detained (Ida, 2019). In the words of one activist, it is a “treacherous” strategy, but also brutally effective, because very few detainees will turn down the chance to be released, especially when ill. The immigration staff are experienced in the strategic use of provisional release (Nomoto, 2020).

While the release of some detainees would ease crowding and reduce the risk of viral outbreaks inside detention centers, being let out in these conditions on short notice without any resources has its own set of problems. So much so that some detainees have chosen to preemptively withdraw their application for provisional release and stayed inside the detention center. This calculation is of course a difficult one. Even recognizing the risk of leaving, one detainee we talked to was also aware that he could be jeopardizing his own application for future release. He does not know if he can resume his application once the emergency has passed or if he “goes to the end of the line.” Perhaps he has lost the chance to ever reapply. Being under indefinite detention—as they all are—only makes the situation worse. No one knows, but as one Nigerian who spent time in the detention center two years ago explained, this is part of the systematic attempt to keep asylum seekers always off balance and fearful, and to encourage them to “self-deport.” During this research, we have come to see predicaments such as these emblematic of the sets of bad options that every refugee faces before, during and after seeking asylum anywhere. In Japan, these bad options are largely a result of intentional policy decisions, as we have seen above.

Those who do opt to leave the detention center—which is almost everyone who is given the opportunity and with means to make it happen—have no medical insurance. As an asylum applicant, they are not eligible so despite the fact that they are leaving a situation due to the threat of infection, and entering a country in the middle of a pandemic so severe that the country is under a “state of emergency,” they are not tested nor are they able to get any treatment if they get sick. They cannot pay for their own health care because they are released without any money, and they cannot work to earn money because they have no work permit. Their movements are strictly monitored, so much so that if they cross prefectural borders to seek support without prior written permission (for example, to seek out the limited support resources that are still available for refugees), they risk immediate re-detention. In these corona times, most of the few groups who still provide support refugees are not fully functional, and the ones that are functional, are hard to find. In the past, due to the inability to find support, we have often met refugees who end up sleeping on the street for some period, usually upon arrival into Japan but also just after being released, a situation that posed serious hygiene problem. But as we were told by one Eastern European, “we cannot even sleep on the curb anymore because the police are everywhere, shoo-shooing you away.” Many public spaces that were once available for rough sleepers are no longer so. Provisional release is both limiting and stressful in ordinary times, but in the face of COVID-19, the conditions of being released are, as he explained, like going from prison to prison.

In a country like Japan, where social support for refugees is so weak, much of the help that anyone can get must come from personal social networks. But being “inside” for an extended period usually results in the deterioration of friendships—and potential personal support networks—on the outside. (As soon as detainees began to be released, Barbaran began receiving 10-20 calls every day from refugees we barely knew, friends of friends, desperately looking for any bit of support or contact, material or human.) Depending upon the ethnic group, and the number of compatriots near Tokyo, there are communities scattered through the Kanto region, but unlike earlier generations of immigrants (such as Chinese, Korean or Brazilian, who have established some community of support, most of the Africans or Middle Easterners do not). Most vulnerable are those who were detained directly from the airport, never having set foot in Japan, and having no knowledge of the language, practices, or culture, and never having developed any networks. There are some shared houses, usually for those from the same country, that also welcome those just released from detention to stay for a while. But during COVID-19, many of those refugees are too frightened to open their doors to others, especially to those coming from detention. For those whose home country is in civil war, and where refugees from both sides have fled to Japan, they also run the risk of reigniting domestic conflicts that were the very reason they fled in the first place. In instances where the persecution is particularly state directed, such as in Syria and Uganda, the danger of spies and surveillance in Japan is very real. (In this case, the last person you might want to meet is someone else from your own country.) The poor level of support in Japan makes refugees all the more vulnerable to these conditions.

Peter is a case in point. He left Nigeria after he was targeted by the security police for his political activism. He came to Japan because it was the only visa he could secure on short notice. He was arrested at the airport and brought directly to Shinagawa Detention Center. He has never set foot in Japan outside of detention. He suffered greatly inside through flashbacks of his abuse and chronic illness. He thinks he was released because he was not in good health, but this is unlikely. In fact, due to the bad food, lack of exercise and poor medical attention, many others in detention are unhealthy, some of whom were released, others not. While there is a Nigerian community in Kanto, he knows none of them, and approaching strangers, even compatriots, asking for a place to stay, to increase what is often already a crowded share housing situation, is not easy. He was fortunate to find a bed at a Christian facility in Kanagawa, so he does have a roof. “I am afraid to go outside,” he explains. “I spend most of my time alone, here, although I am not really sure what sort of place ‘here’ is.” He notes, “in fact, I am more isolated now than when I was inside the detention center.” Still, he does “not dare leave. There is no place to go, and with corona… This is just like being detained all over again.”

Worse to come

The detention center represents an immediate risk to any detainees in a time when COVID-19 exists. It is unlikely that any of the precautions taken during this pandemic wave, including release, would be enough to protect them in case of a resurgence. But as grave as the infection is, in a situation that is plagued by chronic hunger strikes, unexplained or insufficiently explained deaths, it is only compounding a system where the human rights of detainees are chronically threatened and compliance with international norms of refugee recognition is tenuous. COVID-19 has drawn attention to some of these conditions, but as one long-time advocate cautions, “that happens periodically–usually when someone dies. And only if the media gets the story before the MOJ quashes it.” She added that “anyway, people forget pretty soon.”

Presented as a way to address the situation of prolonged detention, in a heartless bit of state theater, in the middle of the pandemic, the government released the latest in a series of reports (Ministry of Justice, 2020) that it called “expert report” to reform the handling of refugees. The awareness of the bad press around the issue of human rights problems caused by prolonged detention has increased (for example, a November editorial headline read, “Japan needs to tackle human rights abuses at detention centers”) (Mainichi Japan, 2019a). It seems that the government has settled on a solution: deport them out of detention, by force if necessary, back to their home country. This “solution” was found to be alarming to many media outlets, with the same Mainichi Shimbun editorial leading with the headline just a few months after the previous one: “Tightening Japan’s immigration regs no excuse to trample human rights” (Mainichi Japan, 2020c). Some activists and lawyers have called this proposal tantamount to a “full criminalization” of refugee asylum seekers, treating asylum seekers whose application is rejected as law breakers unless they self-deport right away. In substantial departures from the current system, these proposals are said to include the elimination of asylum applicants’ right to appeal their rejection of their application, and the elimination of their right to reapply for asylum, even where there is new information pertaining to their case. (No one is entirely sure because the full set of proposals have not yet been released.) Moreover, in a move that is difficult to reconcile with Japanese law let alone the very idea of due process, there is also a proposal to begin deportation procedures even while an application is pending. In a chilling swipe at the already thin legal network that represents the asylum seekers and at the civic, religious and community groups who support refugees and asylum seekers, probably even including groups such as Sophia Refugee Support Group, the report suggested that these activities should be considered those of “accomplices” to the criminal activity of the refugees, and as such, subject to criminal prosecution. The callousness and self-evident threat to human rights were pointed out by legal advocacy groups (Forum for Refugees Japan, 2020; The Tokyo Bar Association, 2020) and even mainstream media (above) almost immediately. If this report becomes policy over the next few months, the situation for refugees and asylum seekers in Japan will become much more dire by the autumn 2020, just in time for the second wave of COVID-19.

References

Asylum Insight. (2019). People in onshore and offshore detention.

Barbaran, R & D Slater. (2020, May 4). ‘If the virus gets in, it will spread like wildfire.‘ Japan Times.

Canada Border Services Agency. (2019). Annual detention statistics – 2012-2019.

Forum for Refugees Japan. (2020, June 28). Shūyō sōkan ni kansuru senmon-bu kaihōkokusho `sōkan kihi chōki shūyō mondai no kaiketsu ni muketa teigen’ e no shimin dantai iken-sho [Citizen’s group statement of opinion on the report of the specialized subcommittee on detention and deportation “Proposals for resolving deportation and long-term detention problems”].

Freedom for Immigrants. (2020). Detention by the numbers.

Fritz, M. (2019, November 25). Japan’s ‘hidden darkness’: The detention of unwanted immigrants.

Global Detention Project. (2013). Japan immigration detention. https://www.globaldetentionproject.org/countries/asia-pacific/japan

Human Rights Now. (2019, October 31). HRN releases statement calling for the prohibition of arbitrary detention in immigration facilities in Japan and related legal reforms.

Human Rights Now. (2020, January 22). HRN issues a joint statement urging the Government of Japan to accept a country visit by the UN working group on arbitrary detention.

Ida, J. (2019, September 2). Re-detention of asylum seekers in Japan, hunger strikes show strained immigration system. Mainichi Japan.

Ida, J. (2020, August 7). Nyūkan shūyō-sha de hatsu no kansen kakunin [First infection confirmed by immigration detainees]. Mainichi Shimbun.

Immigration Services Agency of Japan. (n.d.-a). Kari hōmen kyohi handan ni kakaru kōryo jikō [Points to consider regarding judgment of provisional license].

Immigration Services Agency of Japan. (n.d.-b) Nanmin nintei tetsudzuki zukai [Refugee recognition procedure diagram].

Immigration Services Agency of Japan. (n.d.-c). Taikyo kyōsei tetsudzuki oyobi no shukkoku meirei tetsudzuki no nagare [Deportation procedure and departure order procedure flow].

Immigration Services Agency of Japan. Shūyō shisetsu ni tsuite [About accommodation facility] [Online image].

International Detention Coalition. (2020). IDC position on Covid-19.

The Japan Times. (2014, December 3). Immigrant detention centers under scrutiny in Japan after fourth death.

The Japan Times. (2019, November 27). Japanese bar association says long-term detainments of foreign nationals on the rise.

The Japan Times. (2020, May 1). Japan to release immigration detainees as centers fear virus outbreaks.

Katz, M. (2020a, February 29). The world’s refugee system is broken. The Atlantic.

Katz, M. (2020b, April 16). ICE releases hundreds of immigrants as Coronavirus spreads in detention centers. NPR.

Levin, S. (2020, April 4). ‘We’re gonna die’: migrants in US jail beg for deportation due to Covid-19 exposure. The Guardian.

Mainichi Japan. (2019a, November 11). Editorial: Japan needs to tackle human rights abuses at detention centers.

Mainichi Japan. (2019b, November 20). Intensifying rights abuses against foreigners held in detention put Japan on dangerous path.

Mainichi Japan. (2019b, July 9) Japan’s hidden darkness: Deaths, inhumane treatment rife at immigration centers.

Mainichi Japan. (2020a). `Nanmin sakoku’ wa ima [“Refugee isolation” is now].

Mainichi Japan. (2020b, June 21). `Watashi ni jiyū o kudasai’ Tōkyō nyūkan shūyō gaikoku hito ga uttae chōki-ka, retsuakuna kankyō ni kōgi demo [“Give me freedom” Tokyo immigration detainee appeals for protest against prolonged and poor environment].

Mainichi Japan. (2020c, June 22). Editorial: Tightening Japan’s immigration regs no excuse to trample human rights.

Ministry of Justice. (2015, September 15). Nanmin’ninteiseido no un’yō no minaoshi no gaiyō ni tsuite [About the outline of the review of the operation of the refugee recognition system].

Ministry of Justice. (2018, January 12). Nanmin’ninteiseido no tekisei-ka no tame no saranaru un’yō no minaoshi ni tsuite [Regarding further review of operations for the proper refugee recognition system].

Ministry of Justice. (2020). Hōkoku-sho sōkan kihi chōki shūyō mondai no kaiketsu ni muketa teigen [Report: Proposals for Resolving Repatriation and Solving the Long-Term Containment Problem].

Nomoto, S. (2020, January 13). Hunger strikes spread in Japan’s migrant detention centers. Nikkei Asian Review.

Osumi, M. (2020, April 21). Spread of COVID-19 in Japanese prisons spurs calls for releases. The Japan Times.

Oxfam. (2016). Where there’s a will there’s a way: Safe havens for refugees from Syria.

Slater, D. , Robin O’day and Flavia Fulco, (under preparation). The Collapse of the Refugee System in Japan.

Tamura, M. (2020, June 27). Asylum seekers in Japan face battle for survival in time of coronavirus. The Japan Times.

Tanaka, C. (2018, May 21). Japan’s refugee-screening system sets high bar. The Japan Times.

The Tokyo Bar Association. (2020, June 22). `Sōkan kihi chōki shūyō mondai no kaiketsu ni muketa teigen’ ni motodzuku keiji batsu dōnyū-tō ni hantai suru kaichō seimei [Chairman’s statement against the introduction of criminal penalties, etc. based on “Proposals for avoiding deportation and solving long-term detention problems”].

Tokyo Metropolitan Government. (2020, May 13). Message from Governor Koike on the Novel Coronavirus.

UNCHR (United National High Commissioner on Refugees). (n.d.). Information for asylum-seekers in Japan.

UNHCR (United National High Commissioner on Refugees). (2002). Selected indicators measuring capacity and contributions of host countries.

UNHCR (United National High Commissioner on Refugees). (2007). Advisory opinion on the extraterritorial application of non-refoulement obligations under the 1951 Convention relating to the status of refugees and its 1967 Protocol.

UNHCR (United National High Commissioner on Refugees) (2020). The 1951 Refugee Convention.

Notes

Some of this material has been published by the Japan Times in a much-abbreviated form (Barbaran & Slater 2020).

For a very good series of articles on the contemporary situation of refugees in Japan, see Mainichi Shimbun 2020a and 2020e. The Mainichi has emerged as by far the most consistent and well-informed mass media outlet covering refugee issues in Japan.

For the MOJ’s flowchart of the refugee recognition procedure, see here. For an English version of some of this information, see the summary by UNHCR and JAR, see here.

In Japanese governmental documents, the addition of the prefix “so-called” (いわゆる) is not intended to cast doubt on accuracy of the designation of “fake.” Instead in the documents it seems to usually be used to soften the harshness of the term “fake,” thereby shielding the MOJ from accusations of prejudice about applicants who have not gone through the full evaluation process.

The term “fake refugee” does not seem to have an agreed upon definition. In Japan as in many countries around the world, the discourse of “fake refugees,” is usually part of nationalist and nativist appeals. Currently, we see this discourse in France, Korea, the UK and the US, in particular, although the fear of fake refugees does not seem to drive policy in these other countries to the extent that we see in Japan. For a discussion of the dynamics of “fake” in Japan, see Katz 2020a.

For comparative figures to the U.S., Australia and Canada, see [Freedom for Immigrants, 2020; Asylum Insight, 2019; Canada Border Services Agency, 2019] respectively.