Abstract: There are 608 “children’s homes” (児童養護施設 jidō yōgo shisetsu) across Japan that care for children and adolescents whose parents are unable to care for them (even though in many cases, their parents are known and still in contact with them). The causes for separation vary, including financial or psychological pressures, often taking the form of neglect or abuse. Institutionalization of any kind is always difficult for both children and their caretakers. Inside the children’s homes, the situation is difficult due to limited staff and tight budgets. The onset of COVID-19 has meant a dramatic decrease in the support services, staff, and resources that these institutions can provide, putting an already vulnerable population at added risk. Based on interviews with administrators at some of the leading nonprofits working with these children, this article lays out both the immediate difficulties within children’s homes during this difficult time, and the longer-term challenges they face in providing support for these young people.

Key Words: COVID-19, vulnerable populations, children’s homes, child abuse, child poverty

Introduction

In many countries around the world, some families or single parents cannot or choose not to raise their own children. In those cases, the state or private groups often step in to assume responsibility for these children. In Japan, a loose network of non-profit organizations serves the needs of different populations of children with different levels and types of care that the state cannot provide. One characteristic these institutions share is they are all run on a limited budget, with small staff and few resources. Such precarious conditions often mean that any disruption to their work can have dramatic effects. While for most of us, COVID-19 has required that we alter our routines and practices to protect ourselves from infection and to adjust to the different mitigation orders (social distancing, staying at home orders, etc.), those who are already institutionalized are more vulnerable to infection and have less flexibility in adjusting. As all of these organizations struggle to protect and support the children, we see just how vulnerable they are on an everyday basis and how chronically vulnerable the institutions and thus the children inside are during a pandemic or similar emergency.

One of the types of institutions in Japan are called jidō yōgo shisetsu (児童養護施設), usually translated into English as “children’s homes.” The children come from families that are financially or otherwise unable to care for the children, although the children and administrators at the homes often retain some contact with the parents. These homes are residential facilities that are designed to care for children while they attend regular school until the completion of high school. They are nonprofit entities licensed by the state.

I interviewed administrators at nonprofit facilities working at or with children’s homes or their parents, asking them to share the challenges that they have faced due to COVID-19 and their experience in managing these facilities more generally. Because any institutionalized population has to be particularly careful to protect itself from infection, the homes have had to curtail almost all contact with the outside world; not only can the children not go to school, they cannot have any contact with other children or even their own parents. The administrators’ reports emphasize the fact that that preventative isolation, lack of sufficient staff support, and insufficient resources greatly increased the difficulty both for the children and staff. They often spoke about the stresses these young people face due to being physically isolated and socially cut off from school friends and family. In the longer term, they worried about the effect this isolation might have on their future opportunities as they begin to transition out of the children’s home. This article outlines the immediate precautions taken to protect the children from infection, and the efforts being made to support the children maintaining some workable routine in what amounts to a lockdown.

Protection of Children in Japan

The range of support institutions with different missions and target populations point to the complexity of the situation and inevitable overlapping of missions and gaps in the support network. Other facilities in the alternative care system include maternal and child life support facilities (母子生活支援施設 boshi seikatsushien shisetsu) for children and mothers fleeing family violence; child psychotherapy facilities (児童心理治療施 jidō shinri chiryōshi) for those requiring regular psychological care; independent living group homes (自立援助ホーム jiritsu enjo hōmu) for 15 to 19 year-olds who have left other care facilities; infant care facilities (乳児院 nyuuji-in) for those up to age 2; foster parent homes; foster family group homes (ファミリーホーム famirii hōmu or 小規模住居型児童養育事業 shōkibo jukyō-gata jidō yōiku jigyō) where five to six children live with a family; and kinship-based foster parents (親族里親 shinzoku sato-oya) where youth live with grandparents or older siblings.

Children’s homes are sometimes referred to as “orphanages” in English; however, since most youth have living parents, many of whom are still in contact with the children, many nonprofit leaders refer to these as ‘Children’s Homes’ or ‘Child Welfare Centers.’ Youth may stay in the homes until they graduate from high school or leave the education system after age 15 (Human Rights Watch 2014). The children’s homes are designed to provide basic needs – shelter, food, clothing, support from neglect, and a space that is safe from the abuse many of them suffered at their own home. In 2018, children’s homes housed 27,026 young people living in 608 homes throughout Japan and accounted for 60% of all children not living with their parents. (As a point of reference, of the approximately 45,000 children not able to live with their birth parents, 86% are living in orphanages and 13% are in foster care.) The average age listed was 11.5 years old and youth stay in these homes for an average of about five years, not necessarily consecutively (MoHLW 2020). Officially, these are institutions for six or more children aged two to eighteen years old who cannot live with their parents.

Children may be placed in homes due to parents being sick, disabled, or poor, but the main causes are neglect or abuse. Child welfare laws protect children from dangerous practices which are legally categorized as neglect, abuse, absentee parents, leaving children unattended, abandonment, and refusal of childcare. More than 45% of children are placed in homes for one of these reasons. 65.6% have experienced some sort of abuse including physical abuse (41.1%), sexual abuse (4.5%) neglect (63.0%) and psychological abuse (26.8%). For all alternative childcare facilities except infant homes, the rates of abuse exceeded 50% (MoHLW 2020). In 2017, a new policy was enacted aiming to place pre-school children in foster care instead of children’s homes, however this met opposition by local governments and some children’s homes. (Human Rights Watch 2017). Decisions regarding the placement of children in Japan are made at the local government level by child guidance centers, which are generally predisposed to placing youth in institutions, as opposed to adoption or foster care. According to Human Rights Watch, 78% of child guidance centers indicated that children are placed in institutions instead of foster care based on the preference of the birth parents. The structural issues are quite complex, and details can be found in the report to the United Nations (HRW 2017).

Most of the children, calculated at 93.3% of the 27,000 youth in children’s homes, have 1 or 2 parents living, and 97.9% of them were from “single parent homes.” While less than 20% have “no interaction” with family members, the majority, about 65%, have some type of regular communication with parents 2 to 11 times a year. Despite having living relatives, when these young people leave the homes and enter society upon leaving junior or senior high school, there are no familial safety nets to support them in their transition to adulthood (Bridge 4 Smile). This includes finding a job and an apartment.

These residential facilities house children who go to school during the day, and then return at night. Most of them, about 93.4%, attend school regularly and 56.4% reported “no particular problems with schoolwork,” while more than 36% were reportedly behind in school. They also face other challenges: 36.7 % have some type of disability, mostly intellectual or psychological disabilities, 47.5% have developmental disorders (autism spectrum), 37% have ADHD, 29.2% have reactive attachment disorder (a behavioral disorder whereby there is a “distorted relationship with parents”), 12.6% have intellectual disabilities, and 9.7% have PTSD (ibid.). Under the COVID-19 precautions, these children are further challenged.

The following are the most active nonprofit organizations that support the children at the children’s homes, and who have provided the information for this paper. In total, I contacted 25 children’s homes by telephone and email.

- Mirai no Mori works to build the capacity and potential of youth in children’s homes by engaging them in outdoor activities (Oka Kozue, Executive Director).

- You Me We’s primary mission is to help children in the homes “to become fully capable and financially independent young adults as they reach the age of 18 and prepare to leave the home (Michael Clemons, Founder, Executive Director).

- Bridge 4 Smile (B4S) focuses on helping prepare teenagers for post-orphanage life, developing both their hard and soft skills (Uemura Yurika, Communications Director).

- Hands on Tokyo (HOT) promotes civic engagement through partnerships between organizations needing support and people who want to get involved (Kawaguchi Motoko, Executive Director; Ashma Koirala, Program Director).

- KIDS DOOR is a nonprofit organization working with lower income families (Alexander Benkhart, Program staff).

- Ashinaga provides educational support to orphaned children worldwide.

- Lights on Children (LoC) works for children who do not live with their parents due to abuse, poverty, or illness.

Stresses and pressures faced

In April, Lights on Children (LoC) conducted a survey of children’s facilities, including children’s homes, to assess COVID-related impacts and concerns. Of the responding institutions, 74% mentioned stress on children, and 50% concerns about education. Concern for those who left the facilities after the March graduation was another primary issue (Lights on Children 2020). HOT and Bridge4Smile both expressed the sentiment that the stresses these children experience are similar to others of a similar age, only made worse because many have experienced abuse – grappling with the resulting trauma is amplified by isolation (Uemura 2020). Likewise, Mirai no Mori reported that care workers emphasized that the stress generated “more fights between the kids” (Oka 2020).

Social distancing

People all over the world are struggling with cabin fever due to COVID-19 stay-home measures; however, most are not doing so while living with a large group of unrelated persons sharing a communal space. Staff in such facilities have been at a loss as to how to secure opportunities for learning and play while also preventing the spread of coronavirus (Lights on Children 2020). Care workers were directed by government authorities to adhere to social distancing without specific directives, which is challenging given the lack of space. Particularly in more densely populated areas such as Tokyo, the homes are operating at or over capacity (Uemura 2020).

Children’s homes have different rules regarding social distancing, and some have separated the children into groups of four to six that are not allowed to mingle outside of these small groups. The shared facilities – bathrooms, toilets, and eating areas – pose the biggest health concerns. In some homes, shifts have been created to determine when each person can take a bath or eat, resulting in further stress and conflict (Koirala 2020). Most of the children’s homes have some type of courtyard or small outside space, and they’ve been trying to use those spaces as much as possible (Oka 2020). Some younger children refuse to separate themselves from the care workers and have become more competitive with each other for their attention (Koirala 2020).

Isolation from the world outside

Losing connection with the world outside the home can result in further isolation. Even before this crisis, the children’s connections to those outside the home was limited, and many caretakers worried about further restrictions under the COVID-19 pandemic (Oka 2020). Lack of internet access has served to isolate the children even more. Online programs – if people have access – provide a chance for reconnection (Benkhart 2020). The lack of WiFi bandwidth, overhead projectors, and computers in some of the homes is proving a challenge (Clemons 2020). Furthermore, when there are only a few computers in each home due to tight finances, these are often the PCs that the staff need to use for work (Uemura 2020), making it difficult for the children to use them in any effective manner.

The need for routine

There is a struggle to get children to study and to keep them occupied and engaged; a set schedule can help to maintain some semblance of order and normalcy (Clemons 2020). Homes find it hard to get the children not to feel like they’re just on a “lockdown vacation.” Mirai no Mori responded by creating activity kits which include songs, videos, and activity sheets based on the programs they do in their camp and weekend programs. For example, Nature Bingo has been adapted so that instead of looking for animal footprints, they find leaves on their own grounds. Cooking tutorials, such as for french toast, a popular camp breakfast, keeps the camp spirit alive in these difficult times. They plan to send out kits every other Friday through July to connect with the children while also serving as a channel for communication with the outside world and to support the care workers. Feeling connected through activities and a set schedule may not only relieve stress from being cooped up, but also help motivate youth to study (Oka 2020).

Managing education needs

Based on preliminary research, some national and private schools have started online learning, but most public schools are simply giving out worksheets to be completed at

home. Kids Door is still collecting data to better determine what they can do, but has launched some phone-based support (Benkhart 2020), while other organizations equate providing educational support with online programs, despite the fact that many students lack internet access.

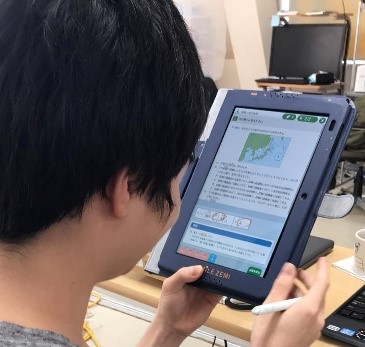

Many homes did not have wifi access, which is why even prior to this crisis, You Me We had already made great efforts to distribute 500 computers and tablets to young people and staff. They also connected some homes to Skype so that volunteers and teachers could contact children remotely (Clemons 2020). A common sentiment among staff was that long-term, online and computer accessibility would have positive impacts once everything was put in place. Not only can it give youth greater access to information and promote the development of skills, it could also foster different ways of learning that some youth might find rewarding. The push to “go online” has the potential to bring about new opportunities, given lasting infrastructure development, but it is also an additional cost to Children’s Homes already on tight budgets.

Homeschooling

The children’s inability to keep up with schoolwork weighs heavily on staff, and while care workers play an important role in helping youth with homework (Koirala 2020), they are not teachers. Care workers are doing all they can to help youth keep up with their schoolwork, but children aged 2 to 18 years old, with a variety of needs, need support all the time. Perhaps the best they can do is help them not get too far behind (Oka 2020).

The ramifications of being out of school for an extended period poses a more severe challenge for children in homes. Mindful of the fact that children’s home residents tend to have lower school performance and difficulties due to disabilities or trauma, nonprofit leaders have expressed concern that children would refuse to return or drop out of school due to the disruption of routines and students’ inability to keep up with their studies (Uemura, Oka, Watanabe 2020).

For high school students, keeping up with studies is just one of their struggles. The transition to living on their own is always going to be stressful, but the coronavirus has brought about new and unexpected unknowns. Working to save money and secure any type of employment is intrinsic to their post-home survival since they have no other safety net and no family home to go back to. If teenagers are unable to work part-time due to the pandemic, this also means they will experience additional difficulties in paying their mobile phone bills. This not only further isolates them from their social network, but also holds them back from potential work opportunities (Uemura 2020).

Family Visits and Socialization

Impacts on the children’s relationships with family members have become a more pressing issue. During the emergency declaration, care workers had to place a priority on health, so visits from outside persons, including parents, had been restricted in some homes (Oka 2020). The fear of losing family connections and the potential for re-abandonment can have serious consequences (Uemura 2020). The loss of parent-child meetings is particularly devastating in cases where there was the expectation of reunion. Parents of those in homes tend to have unstable employment, and some work at jobs with high risks of infection such as nursing, elder care, food service, and hospitality businesses (Ashinaga 2020). Technology can ease some of the stress by helping maintain contact with parents, family members, teachers, volunteers, and friends, which is why the availability of video calling platforms such as Skype is meaningful (Uemura, Clemons 2020).

The socialization aspect of school is extremely important. Kids go to different local schools, which gives them the opportunity to meet people who can serve as role models for them, such as teachers and volunteers. Not being able to accept volunteers into the homes to assist with school work, to play games with, or to provide computer, life skills, or English classes, at the moment when exposure to the outside world has been lost, poses a particular challenge (Uemura 2020). Young people in homes have a limited number of adult role models – usually just care workers and teachers. Children who can go outside the homes can meet parents’ friends and other people with different jobs and interests. These potential role models expose youth to new possibilities (Koirala 2020). The lost potential of broadening each child’s world because they cannot meet new people from whom they can learn may have long-term effects (Oka 2020).

There is, however, a potential silver lining: if more attention is brought to the plight of these children, it could lead to more active collaboration between children’s homes and advocacy workers. As of yet, there are only a few external support groups advocating for these children who otherwise have no power over their circumstances (Benkhart, Uemura 2020). More partnerships at the local level between nonprofits and local governments, the business sector, and social welfare agencies could result in more people sharing expertise and contributing to the growth and development of these young people into active, successful members of society (Clemons 2020).

A Broadened Perspective

The long-term impacts of the emergency order on these youth are difficult to predict. Much depends on how long they are isolated, when they can go back to school, when outside visits can resume, and whether lasting changes can be made.

The current health disaster shows that the divide between youth who live or don’t live with their families as well as those with or without resources is growing because the underlying issues that contribute to the difficult home situation that these children face has not been addressed – neglect, abuse, and economic stressors. Children, like others lacking autonomy and power, are particularly vulnerable in these cases (Clemons 2020). In fact, often, in times of crisis, many of these vulnerabilities are compounded, as we see in the increase in reports of abuse. The concern is for those who live in abusive homes. While it is necessary to move some of these young people into more institutionalized children’s homes, such moves come with their own challenges, as I have shown in this article. Beyond just the children who are already in homes or alternative care, attention and empathy should also be extended to those children who should be in care homes but are not. There is an urgent need to protect such children from a range of abuses, but they are often invisible because they are stuck in the place where the abuse is occurring (Oka 2020).

The importance of nonprofit work has increased due to the onset of COVID-19, but as outlined here, the most difficult conditions these children face today are chronic challenges that most face every day of their lives. Connecting with these youth through activities, whether online or offline, can do more than just keep them busy and alleviate stress: it can also provide new stimuli and open up their worlds that have been limited by the circumstances. However, it will take more than just kind words aimed their way – rather, it is imperative that actions be taken in the form of the investment of resources, including money, time, and expertise, into these youths’ livelihood and welfare.

I offer these guidelines to those seeking to help:

- Learn more about the situations faced by children in alternative care and children’s homes. Educating yourself and helping those around you to be more well-versed on the issues can create much-needed understanding so that these children are not forgotten and abandoned by society.

- Consider changing your own attitudes towards these children – rather than seeing them as pitiable, understand that they are vulnerable and need support to reach their full potential.

- Donate cash! Technology and new program development all cost money.

- Get involved directly by volunteering with IT and educational or other programs

References

Ashinaga Ikueikai. 2020. Scholarship Student Emergency Questionnaire for Mothers and Guardians, April 16.

Benkhart, Alexander, Program Staff at Kids Door. 2020. Zoom Interview and Email communication, May 14.

Bridge for Smile 2020. Report on the effect of corona crisis on people who have recently left Children’s homes, April 20.

Clemons, Michael, Founder of You Me We. 2020. Zoom Interview and Email communication, May 11.

Fukuyama, Tetsuro. 2020. Conversations with Watanabe Yumiko, Kids Door, and Tetsuro Fukuyama, Secretary-General of the Constitutional Democratic Party on the Educational Gap of Children in Corona, April 20.

Government of Japan, Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (MoHLW). 2018. “Results of a survey of children admitted to orphanages (data as of February 1, 2018),” Summary of Survey of children in childcare facilities, Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare, Social Support Bureau & Disability Health and Welfare Department, Children’s Family Bureau, Feb. 1.

Government of Japan, Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (MoHLW). 2016. “About social care facilities,” Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare Social Support Bureau and Disability Health and Welfare Department, Children’s Family Bureau.

Human Rights Watch. 2017. Submission to the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child concerning Japan 79th pre-sessional working group, Nov. 14.

Human Rights Watch. 2014. Without Dreams: Children in Alternative Care in Japan, May 1.

Kawaguchi, Motoko, Executive Director of Hands on Tokyo (HOT). 2020. Zoom Interview, May 14.

Kids Door. 2020. April 28, 2020~May 16 2020, Covid-19 Support Package Recipient Survey, Shared by organization after interview.

Kids Door. 2020. Don’t lose to corona! Distribute the home study support pack to 10,000 children, May 9.

Koirala, Ashma, Program Director of Hands on Tokyo (HOT). 2020. Zoom interview, May 14.

Lights on Children. 2020. Tokyo orphanages struggle with online learning support-urgent questionnaire results, April 13.

Lights on Children. 2020. Responding to Rights-of-Children due to the spread of new coronavirus infection, May 1.

Oka, Kozue, Executive Director of Mirai no Mori. 2020. Zoom interview and email communications, May 11.

Uemura, Yurika, Communications Director of Bridge 4 Smile. 2020. Zoom interview and email communications, May 12.