“If our sin as scientists was to make and use the atomic bomb,” Leo Szilard, famed physicist would admit, “then our punishment was to watch The Beginning or the End.” Szilard’s exposure to the 1947 MGM movie, however, went far beyond merely enduring a viewing of the first Hollywood drama about the creation and use of the bomb. The previous year he had traveled from Chicago to Los Angeles to offer his input on key scenes, then signed a contract agreeing to be portrayed in the movie–and after much cajoling, convinced Albert Einstein to sign his own approval.

Szilard would not be the only atomic scientist to express disappointment in the big-budget film, which drew mixed reviews from movie critics and modest box office receipts. The project, after all, had shifted 180 degrees from its inception, when it was inspired by the scientists as a warning against building new and bigger bombs. Now it was little more than error-ridden, pro-bomb propaganda.

It had started with an urgent letter from a worried scientist at Oak Ridge to his former high school chemistry student, actress Donna Reed. Now it concluded with a scene at the Lincoln Memorial, with the one voice of conscience remaining in the script, a young scientist named Matt Cochran, addressing his wife as a ghostly figure. Despite having just perished in an accident while arming the Hiroshima bomb (which would then slaughter 125,000 others), he assures his widow, in cloudy, apparitional form, “God has not shown us a new way to destroy ourselves. Atomic energy is the hand he has extended to lift us from the ruins of war and lighten the burdens of peace…. We have found a path so filled with promise, that when we walk down it we will know that everything that went before the discovery of atomic energy was the Dark Ages.”

This “cheery imbecility” would be mocked by James Agee in his Time magazine review. Life magazine would call it “hokum” and “full of flossy but trite hopes for a better world.” The studio’s unique, if desperate, trailer for the movie utilized a fake “Inquiring Reporter” interviewing B-list actors and actresses pretending to be movie goers.

How and why did that transpire? Once MGM bought out a rival project (with a script by none other than Ayn Rand) from Paramount, it had clear sailing to take any route it desired. Legendary studio chief Louis B. Mayer, in approving the project, had insisted that it become the “most important” movie he would ever present. Producer Sam Marx was relatively liberal for a movie executive in that era of Hollywood. Mayer, in contrast, was a hardcore conservative and turned the overall managing of the project to one of the most rightwing activists in town, James K. McGuinness (later a prominent promoter of the blacklist and McCarthyism).

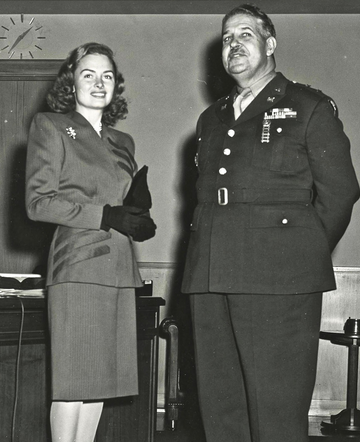

Even more critical to the outcome, the studio paid the then-enormous sum of $10,000 to General Leslie R. Groves, director of the Manhattan Project, for his exclusive services, and essentially granted him final approval of the entire script (a power he would exert, to the max). The scientists served only an advisory function. They were able to successfully fact-check some technical aspects, but had no authority to force any changes in tone or message and were paid little or nothing for their services.

Ultimately, mainly thanks to Groves, the movie would not only fully endorse the decision to use the bomb against Japan, but re-write history to support that conclusion. For example, it repeatedly referred to the U.S. “showering” the target cities with leaflets explicitly warning that a new weapon was on the way–while eliminating plans to reveal some of the human effects of the bomb on the ground in Hiroshima. And Nagasaki? In the end it wasn’t even mentioned once.

Groves with actress Donna Reed, 1946

Finally, the White House, which also had veto power in its pocket, got crucially involved, with Truman and his press secretary Charles Ross, ordering a costly re-take (an unprecedented order from the Oval Office in the history of Hollywood) of the key scene showing the president explaining his reasons for deciding to drop the bomb. Truman even got the actor playing him fired. He wanted someone with more of a military “bearing.”

What follows is an excerpt from The Beginning or the End: How Hollywood–and America–Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb.

This picks up with the writing and revising of the film’s script at about its midway point in the spring of 1946.

***

J. Robert Oppenheimer wasn’t the only critical figure in the atomic bomb regime to finally receive an MGM script this month. He had only helped create the new weapon; President Truman had ordered its use, twice, against Japanese cities. The two men, therefore, were among those who shared responsibility for what had happened, and what might happen next, in the “atomic age.” As displayed in their single Oval Office meeting, only one of them seemed to harbor any regrets about his role.

Hume Cronyn as Robert Oppenheimer in the movie

Truman, in fact, seemed more perplexed and distant from the bomb than remorseful. At a Cabinet meeting he admitted he did not know how many atomic weapons were in the U.S. arsenal and did not really care to know, earning a lecture from his secretary of commerce, Henry Wallace. He also mused to Wallace that he was worried that atomic energy would one day reduce the number of hours in an average workweek, causing laborers to “get into mischief.” By now, Truman’s rising popularity, following V-J Day, had faded in the face of crippling labor strikes and threats of same, particularly involving the railroads. Common wisecracks around DC and in the press claimed, “To err is Truman” and “I’m just mild about Harry.”

Now, in any case, what would Truman think of the MGM script?

Apparently it seemed fine with him, at least at this stage (only later would major complaints and extreme pressure ensue). His press secretary, Charles Ross, voiced only three fairly minor areas of concern to MGM’s Carter Barron, after revealing that, yes, Truman himself did read the script. Ross ordered removed any reference to the president supplying the title of the film. The actor playing Truman must be filmed only from the rear. Also, the White House wanted excised any reference to Truman, as senator, rising to fame leading the committee investigating military waste, including the massive spending on some secret operation not yet revealed as the Manhattan Project. They may have feared it made him look like someone who might have exposed and thereby derailed the bomb project. So that had to go.

MGM’s Barron quickly jumped to the task, and a few days later wrote a formal letter to Ross to “confirm my agreement on behalf” of MGM to execute those deletions. Barron closed by expressing gratitude “for your speedy attention to our problem.” Ross would reply the same day, explaining that if these promises were kept the White House would have “no objection” to MGM moving forward in making their picture, although of course the president would not offer any public endorsement.

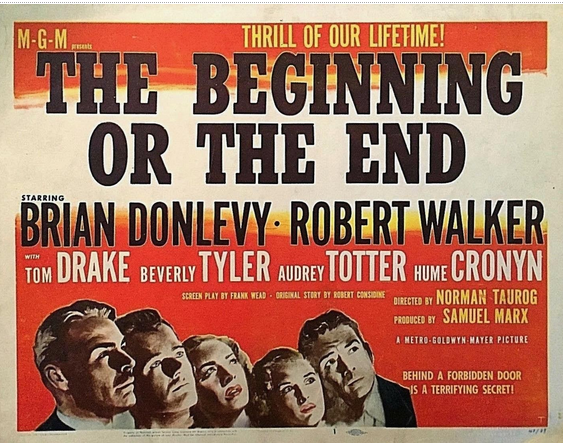

Publicity image for the movie (the film was in black & white, however)

Soon after, an MGM press release announced that the studio had secured approvals to be impersonated in the movie from Truman, Groves, Oppenheimer, Fermi, Enola Gay pilot Paul Tibbets, and others. “Never has a single motion picture presented such an array of prominent living personalities,” the release boasted. One other, even more famous scientist, Albert Einstein, who had just received the screenplay, later granted his approval.

So, what remained in the heavily revised, script that was being circulated to a few key players? Changes were still being made week to week. Frank Wead’s original manuscript was again filled with messy pencil edits, major cuts and hand-scrawled inserts. A note in one of the scripts helpfully advised that in pronouncing Oppenheimer’s name please know that it’s OPP as in TOP.

Elsewhere, the script was adapted to emphasize the desire to portray the atomic attack in a heroic way, and as one absolutely necessary to save America from meeting the same fate. FDR now claims that his psychological warfare experts told him that the “Japs will fight right down to the women and children.” Now the “light flak” greeting the American bombers near Hiroshima–already an enormously revealing falsehood–has been transformed into “heavy flak.” Even worse, when purely fictional Japanese fighter planes approach the Enola Gay, they are so close (in the movie) that the Americans need to return fire! The accident that dooms Matt Cochran’s life now occurs before Hiroshima, as he arms that bomb, not in the run-up to Nagasaki. This enabled the script to totally eliminate any depiction of the even more questionable second bomb.

Brian Donlevy as Groves and secretary (Audrey Totter)

Even more revealing was the addition of two new, fictionalized, warnings about the Japanese obtaining atomic weapons to greet a U.S. invasion. One of them had Roosevelt musing, “Our latest intelligence worried me . . . the Japs may have atomic weapons before we do.” Groves, as before, claims the half million U.S. death toll in an invasion will climb horribly if the Japanese greet the Allies with atomic bombs. But now, when a top U.S. military adviser warns, “The Germans have sent many atomic experts and materials to Japan by submarine,” all of those in the room “are shocked” (a sentiment that would have been shared by any serious historian, since nothing of the sort ever happened). The adviser continues, “We’re slapping down every sub that shows its nose, but some are bound to get through!”

This desperate rewriting of the script, and history, culminated in the wildest scene yet, adding an element of unintentional black humor to the script.

The setting: a cove near Tokyo very late in the war. Japanese sailors and scientists gaze off over the water with binoculars . . . and spot a submarine surfacing. A Nazi officer with his aides soon comes ashore. He is accompanied by a Dr. Schmidt, Germany’s leading atomic scientist. Professor Okani, a Japanese physicist, greets him, then tells his colleagues that Schmidt has brought uranium “and everything else we will need.” The Japanese have “factories, men and materials” ready for Schmidt to use to make his bomb.

Schmidt says the only reason Hitler didn’t get the A-bomb first was because the German labs could not be protected from Allied bombs, but here on Japan “it will be different.” A Nazi officer booms: “Yes! We are not defeated. We can sink the enemy fleet, wipe out their men and bases and begin to fight our way back to Axis victory.” He adds: “Heil Hitler!” The Japanese respond, “Banzai Nippon!”

And then the kicker. “We have prepared a fine laboratory for you,” Okani tells the Germans, “at our new Army Headquarters in . . . Hiroshima.”

This scene proved to be too much for even Groves to accept, and it would be deleted from the script. Nearly all of the other falsifications remained, however.