Abstract

Japan’s ruling class’s wartime project of militarisation and imperialist domination is well-documented in the English language but the active resistance of the working class and general population is less well-known. Sugiura Masao’s Against the Storm covers the activities of printworkers in the period of Japan’s increasing militarisation, particularly from the Marco Polo Bridge incident of 7 July 1937 to the surrender in 1945. Further context is provided with reference to earlier periods, times when legislation had begun to place restrictions on the political and civil rights of the population.

Key words: labour activism, politics, printworkers, unions.

Introduction

The drive to militarisation was also associated with increased domestic control over the population and ever tighter repression. In 1929 one military leader wrote: ‘Japan must expand overseas to achieve political stability at home.’1 In the early 1930s, Cabinet members repeatedly complained that domestic unrest was a ‘great problem, impeding national defence’.2

Japan’s First May Day in Hibiya Park, Tokyo, 2 May 1920

The bourgeoisie and ruling parties’ fear of discontent in the population, the growing influence of left wing ideas and the impact of social change led to the introduction of repressive legislation such as the Peace Preservation Law (1925). Such laws were used to harass and imprison leftwing activists and sympathisers and over time most members of the small but growing Japanese Communist Party (JCP) were imprisoned. The persecution, torture and murder of communists and sympathisers continued into the 1930s and newspapers carried numerous reports of unexplained deaths in custody. The most well-known was the murder, in police custody, of author Kobayashi Takiji (1903-1933, The Crab Cannery Ship) in 1933.3

There was a police box on every corner and in the neighbourhood where the Club, the organisation created by print workers in Tokyo and the focus of this memoir, operated there was a police station. Police regularly patrolled the neighbourhood. Although surveillance of this kind existed throughout Japan, Sugiura describes how conducting any political activity was made more difficult. Even possession of certain books, if discovered, would have meant arrest. As police repression became even more intense, labour activists assumed that at workers’ meetings there would be at least one person who was a member of the Special Police, many of whom were often stationed in the doorways of every print workshop.

Ruling class actions did not go unchallenged. The period was marked by social upheaval and resistance. In the atmosphere of the 1920s, left wing culture coalesced and became the basis for criticism of militarism. Continued disenchantment with the political system, inflation and austerity policies and limited civil liberties prompted protests, particularly by students, workers, peasants, minority groups and the associated women’s groups. Repression destroyed many social, political and cultural outlets but circles in factories and villages enabled workers and peasants to develop their own independent culture. When the illegal JCP moved underground their goals were advanced through these other groups which played a major role in the mass dissemination of antiwar, Marxist and revolutionary ideas.4

Picnic of Ayumi group at Kinuta Village in Tokyo, May 1936

As for the working class, unionisation rates during the wartime period were quite low, only five per cent, but the period was nonetheless one of intense industrial strike activity. The number of strikes fluctuated but reached 2456 in 1931 and, while dropping in the intervening years, climbed to 2126 in 1937 when 231,622 workers participated in strikes.5 The success of the Tokyo subway workers’ strike in March 1932 encouraged other workers. It is in this context that the Tokyo Printing Company and Yasuhisa strikes of 1935 mentioned in the book took place. These two strikes were actively supported by Club members.

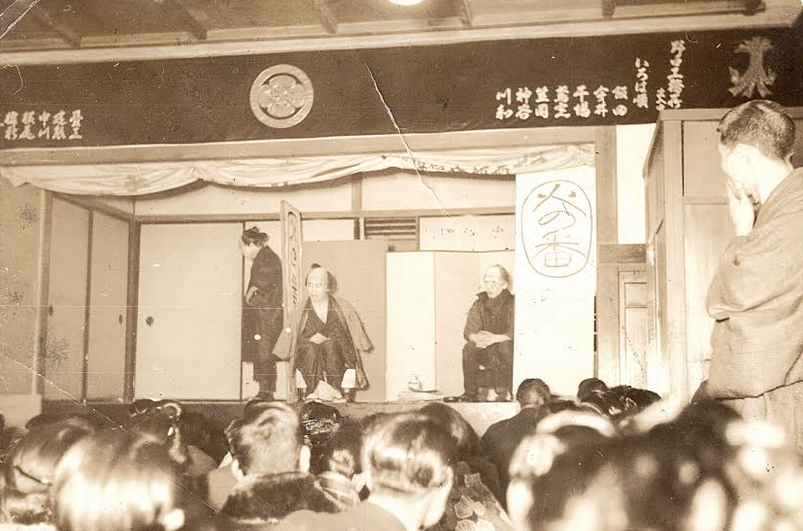

Inauguration of the Printworkers’ Club

14 January 1937

In the face of repression and surveillance, the Club carried out a range of activities and Sugiura’s memoir (which includes recollections from other Club activists) describes how these activities were carried out. Sugiura’s book deepens our understanding of the devastating impact of the war on the population and contributes to the growing body of literature6 which reveals the extent and nature of resistance by the Japanese population to the government’s drive to war. This history serves as an important counterweight to those who believe that Japan’s total population wholeheartedly supported the ruling class’s militarist and imperialist project; that the whole of the union movement capitulated and cooperated with the state’s repression of workers; or that they were completely absorbed into the state-dominated labour front. In my initial interview with Sugiura Masao, he quoted well-known labour movement activist and historian Shioda Shōbei (1921-2009) who said of the Club, ‘Even during the war years, Japan’s labour movement sowed seeds’.7 The following is an excerpt from Sugiura Masao’s memoir.

Facing the Day of Japan’s Surrender from Behind Bars

I greeted 15 August 1945, the day of Japan’s surrender, from a solitary prison cell. The atmosphere that morning was unusual, as there had been no warden’s voice calling us to get up. I ate the substandard meal that was delivered and got ready for work, but no-one came. The warden also did not come and the area around the cell was eerily quiet. From downstairs a sonorous recitation was audible. When I looked out through the peephole the ‘jack of all trades’ trustee, a prisoner who assisted the wardens, was reciting a poem in a sad voice. This man was, rumour had it, a right wing fighter who had tried to assassinate a financier and had been imprisoned for attempted murder. I thought his singing was strange. Usually, if we sang in a loud voice, we were beaten up by the warden. While I was looking out at this scene, there was a signal from the cell opposite mine.

When I opened my food slot, they also had their food slot open and were writing something in the air. After they had written a letter they would nod to ask if I understood. What I deciphered was ‘Japan lost the war’. I knew that Japan’s situation in the war had deteriorated, but to lose! Everything became clear. I bowed deeply and thanked the person in the cell opposite me.

I heard the next day, by the ‘writing in the air’8 method, that the emperor had broadcast his surrender speech. After shutting the food slot, I started to consider how this would affect we prisoners. I thought we would be released soon.

We were not released, nor were we killed: we political prisoners remained locked up until 6 October.

Becoming criminals under bad laws

Late on 6 October, the sound of a key opening cell doors got closer. The warden told me to grab all my things and get out. I snatched my personal effects and left my cell. Outside, when I started to descend to the lower floor, we were told to form a line. I saw my comrade Taguchi. We walked down the long walkway towards the church where the prison governor and chaplain were waiting. The governor, standing before us, began to speak to us in a tone more polite than usual.

Until now, you were kept in here for disrupting the public peace. As you know, Japan lost and the war is over. You are now no longer criminals. From today you are to go home. Even though our points of view have differed so far, from now on we must work together and overcome this difficult period in Japan. Please do not think badly of me.

Hearing the governor’s words, an angry roar rose up from the political prisoners. ‘What are you saying? Now you are saying we are not criminals! Cut the crap. Who is taking responsibility for the fact that we were locked up in here for years? Stop kidding around. Arseholes!’ Gnashing their teeth, some tried to launch themselves at the governor. Others responded with ‘Let’s just get out of here right now. You can argue all you want later.’

Until yesterday, we were criminals under the Peace Preservation Law (1925–45, hereafter PPL) created by the imperial government, and because of this, we had been imprisoned for many years. But now, these laws had been abolished by order of the Allied army, and from today we were not criminals.

Why was I imprisoned? Because we did what would be just a normal thing for any trade unionist to do today.

At the time the Club was organising, the printing industry was largely a non-union workforce. Unemployment was high and workers had no rights. Naturally, we tried to unionise by ourselves, to protect our occupation and jobs as well as our livelihoods. But because we were doing these most natural things under the worst law of the century, the PPL, we were criminalised and imprisoned.

Japan had invaded China but had met resistance from the Chinese people. They smashed all progressive political parties and trade unions and created state-sponsored organisations – the Imperial Rule Assistance Association (IRAA) and the Patriotic Industrial Association (PIA). The government brought Japan’s workers into the war. Those political parties and trade unions that opposed the military course were suppressed and then annihilated, leaving only those political parties and trade unions who supported the government’s war policies.

The Club opposed co-operating with the state and for that the Special Police punished us with imprisonment.

It is said that Japan’s entire union movement during the war years was forced to disband and was reduced to zero. Looking back, though, to that darkest war period, the print and publishing industry union movement continued, preventing workers’ organisations from completely disappearing.

I will tell you about the path that Japan’s union movement pursued during that darkest period, and how, even during the dark repressive period, a small group of workers continued to fight, regardless of the risks.

What did the movement that existed during this repression look like? I want to tell you the story, based on the circumstances of the time and the path we took.

References

Broadbent, K. and O’Lincoln, T. 2015. Japan: Against the Regime, in D.Gluckstein (ed.) Fighting on All Fronts: Popular Resistance in the Second World War. London: Bookmarks.

Cipris, Z. 2015. To Hell With Capitalism: Snapshots from the Crab Cannery Ship, The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus v13, issue 18, no.2 .

Dower, J. 1993. Japan in War and Peace: Essays on History, Race and Culture. London: HarperCollins.

Gordon, A. 1991. Labor and Imperial Democracy in Prewar Japan. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Ienaga, S. 1979. Japan’s Last War: World War II and the Japanese 1931-4. Canberra: Australian National University Press.

Shioda, S. 1982. Nihon Shakai Undō Shi (A History of Japan’s Social Movements). Tokyo: Iwanami Zensho.

Notes

See, for example, Cipris 2015 To Hell With Capitalism: Snapshots from the Crab Cannery Ship, The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus volume 13, issue 18, number 2.