Abstract

This paper explores the parochialism overshadowing the representation of Africa in Wolf Warrior 2, a popular Chinese film released in 2017. Set in Africa, the film portrays the continent as chaotic, characterized by lawlessness, ravaged by war and disease, and destined for doom. Of particular interest to this paper is the role assigned to the Chinese characters, which reveals stereotypes of Africa in the face of a rising Sino-African economic, political and diplomatic engagement which highlights principles of egalitarianism. The article uncovers a “White Saviour Complex” in the film’s Chinese characters in ways similar to Western colonial narratives. This is despite the fact that there is no colonial history linking Africa and China that would substantiate the new face given to this White Saviour Complex. This paper posits that Wolf Warrior 2 reasserts a superiority complex in views of Africa, often bundling the entire continent’s countries into one hopeless entity desperate for a foreign saviour. It further suggests that the film announces China’s displacement of the West on the continent. This paper argues that Wolf Warrior 2 reveals hegemonic anti-African racist stereotypes.

Key words: Wolf Warrior 2, White Saviour Complex, imperialism, Heart of Darkness, Africa, China

Introduction

An audience hungry for action will find everything its heart desires in Wolf Warrior 2: bangs and blasts from bombs spreading shrapnel, tanks rolling across the land, guns blazing, and fists clenched in win-or-die combat, car chases and blood spilling on buildings ravaged by a savage war. Nearly two action-packed hours begin with the hero Leng Feng (played by its director, Wu Jing) saving a fallen comrade’s family from social injustice by brutally beating a man leading a house demolition team. His exploits in the saviour role follow a vengeance mission in Africa.

In the film, Leng Feng is jailed for battering the demolition team’s leader. However, while still in prison, his fiancée – a fellow Special Forces Unit military officer – is kidnapped and murdered by mercenaries in one of the army’s missions, a fact we learn through repeated flashbacks. After his release from prison, Leng Feng travels to Africa in pursuit of his fiancé’s murderers. While there, he becomes entangled in a bloody civil war in a nameless country. He discovers that the mercenaries hired by rebels in the war might have been responsible for his fiancée’s death, and motivated by this revelation, he becomes involved in the war, primarily by attempting to save a Chinese Dr. Chen (played by Qiucheng Guo) who developed an antidote for Lamanhla – a deadly virus that is plaguing the war ravaged country. Leng Feng ends up in a chase with rebels as he flees with a Chinese American Dr. Rachael Smith (played by Celina Jade) and Dr. Chen’s adopted daughter Pasha, having failed to save Dr. Chen. In the course of the action, Feng contracts the deadly virus and falls ill, but is soon cured by the antidote Dr. Chen had been developing before he was murdered by the mercenaries, administered on him by Dr. Smith. Although his heroic acts seem to outstrip his original motivation of vengeance, Feng’s desire to avenge his fiancée’s murder still surfaces when he pursues Big Daddy (played by American actor Frank Grillo), the antagonist, even as he (Big Daddy) retreats following missile attacks on the rebels by a Chinese Navy ship.

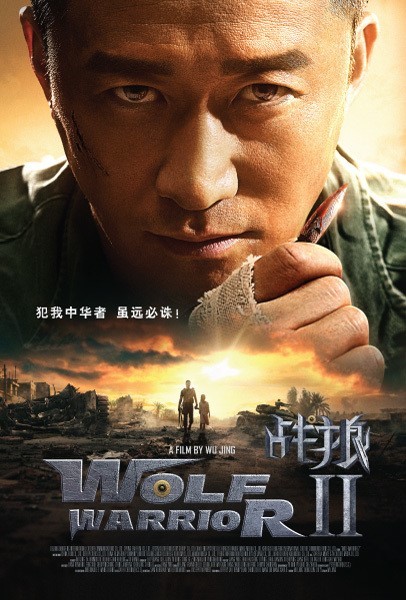

|

Wolf Warrior 2 – released in 2017 |

Released in 2017, Wolf Warrior 2’s theme of Chinese patriotism, coupled with the lively action scenes and a relatively new setting for the Chinese audience, might account for the film’s enthusiastic reception. About thirty days after its release, it became the second film in history to reach US$800 million in a single territory in its cumulative box office collections (in the People’s Republic of China), second only to 2015’s Star Wars: The Force Awakens in the United States (Cain, 2017). Its emergence and reception coincided with what film critics claim to be the search for a Chinese hero equal to those served up by Hollywood, solitary, rescuer-type characters such as Rambo (Phillips, 2017). In Leng Feng, Chinese cinema-goers not only find their Rambo, but also, a figure through which to reassert a racist superiority complex over Africa, which is occurring at a time when Sino-African relations are rapidly expanding in diplomacy, trade and military force. Wolf Warrior 2 gives certain quarters of the Chinese public a sense of pride, a move that parallels Hollywood’s reconstructions of the Vietnam War through a series of action-packed films which glorified US military prowess (despite anti-war campaigns and policies such as Vietnamization that unsettle that narrative). Part of Wolf Warrior 2’s narrative presents the rise of China as a global power with the capacity to undertake foreign rescue missions, albeit subtly through the actions of a single character. It complements expectations of the roles China must play as a rising power: it will have to counter situations whenever its citizens and partners are under threat.

While Wolf Warrior 2 failed to make it into the quota for theatrical releases from Mainland China in Taiwan (ChinaFilmInsider, 2017), the story was different in Hong Kong where it scored $333,000 during its opening September 7-10 weekend, with a 10-day cumulative sales of $681,000 (Chow, 2017). Chow notes that this was surprising, considering the film’s unabashedly patriotic content which in the past was strongly rejected by residents of Hong Kong. With the September 7-10 earnings, the film was fourth among new releases. In North America, the film brought in $1.5M in two weeks of release while by August 11, it had grossed $543K in Australia (Tartaglione, 2017). In South Africa, the Chinese Embassy hosted a reception for the screening in Pretoria after it was released in South African cinemas on 10 November 2017 (The Diplomatic Society, 2017).

However, despite the domestic record-breaking success and the wider global distribution revealing an international appeal, to the African, whose continent is the setting, the plot and characterization of the film presents a different picture. In particular, Wolf Warrior 2 depicts themes and experiences that form a recurring trope in Western colonial art, literature, and cinema. This appears notably in the novella Heart of Darkness, as well as in The Legend of Tarzan (2016), SEAL TEAM 8: Behind Enemy Lines (2014), and Tears of the Sun (2003), among several other Hollywood films set on the continent. The depiction of Africa as a wild world with beautiful scenery and ubiquitous wildlife, with its people and their disregard for life and lack of reason, scarred by wars, poverty, and disease is a parochial representation that has always haunted the film industry’s engagement with the continent.

It is therefore unsurprising that the film does not sit well with the few African cinephiles from the middle-class. In an interview “On Wolf Warrior 2: Thoughts from Africa”, a University of Ghana economics graduate, Seth Avusuglo, argues that to most African cinephiles, Wolf Warrior 2 is just another foreign film trying to tell part of the African story from a narrow point of view to a targeted audience (Hiu, 2018). This is what Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, a Nigerian writer, bemoans as the single story (Adichie, 2009). Avusuglo further posits that as only a marginal fraction of the middle-class frequents cinemas, these educated people would not be comfortable with any negative portrayal of the continent. ‘The depiction of Africa in the foreign media is already a hot issue of discussion. So this won’t sit well with them. It would only be viewed as a hotchpotch of how not to tell the story of Africans’ (Hiu, 2018). The film has also generated negative social media ‘reviews’ across the continent, with some Malawian netizens observing that it is ‘the same narrative of a war-ravaged and disease-plagued Africa waiting for a saviour’.

Scholarly Responses to Wolf Warrior 2

The fame surrounding Wolf Warrior 2 has made the film a subject of scholarly treatment. Academic reviews continue to spring from various interrelated disciplines such as media and arts, with literary discourses dominating the conversation. Second, the film has generated a public discourse that has yielded brilliant essays and newspaper articles exploring various themes in and experiences of the film. Most of the works offering insight into Wolf Warrior 2 have noted the film’s distasteful representation of Africa.

In an essay titled “The Said and Unsaid of the New Worlding of China-Africa-U.S. Relations”, Rofel (2018) points to ambivalence that characterizes Sino-African relations in the film. She notes that one of the film’s main contradictions is China’s relationship with the nameless African country in which the film is set. The essay poses questions that are vital to how both African and Chinese filmgoers reflect on the relationship between the two entities.

As Rofel (2018) notes, Wolf Warrior 2 appears to be trapped between trying to portray China and Africa as allies, and presenting China as superior and a saviour of the African peoples. This creates what Mambrol (2017) calls a ‘complex mix of attraction and repulsion,’ whereby notions of egalitarian Sino-African relations produce a paradox in coexisting with the need to depict China as a powerful military and economic force.

|

Leng Feng holds the Chinese flag high as a truck carrying survivors of the war enters a Chinese evacuation camp |

On the anti-African racist stereotypes, Madrid-Morales (2018) argues that misrepresentation of Africa is recurring worldwide. He notes that Wolf Warrior 2 ‘manages to bring together in a single film all the clichés of Hollywood’s white-saviour subgenre: an unnamed African country affected by a deadly disease descends into chaos as civil war erupts. That is, until a Chinese mercenary comes to the rescue.’ However, Madrid-Morales also draws attention to the fact that the film was not conceived with global audiences in mind. He calls it part of cultural artefacts that speak to domestic audiences for propagation of particular causes (Madrid-Morales, 2018). A similar perception informs Kuo’s (2017) reading, which argues that the film gives the White Saviour Complex a whole new meaning, branding it as China’s own version of the phenomenon. The White Saviour narrative is “a cinematic trope portraying a white character rescuing people of colour from their plight” (Kuo, 2017). Like Madrid-Morales, Kuo similarly observes, ‘like many Western films before it, the specifics of the African setting of Wolf Warrior 2 are irrelevant. The film was mostly shot in China and in Soweto in South Africa, but no country is ever named’ (Kuo, 2017). Hsu (2017), writing in the Financial Review, states that ‘at times, the film feels like a weird exercise in what might be called a “yellow saviour” mentality – a slant on Hollywood’s problematic “white saviour” complex.’ The film copies ‘the same tropes that have fueled Western cinematic representations of Africa’ (Hsu, 2017).

Xiang (2018) agrees with Kuo (2017) and Hsu (2017) in his essay Toxic Masculinity with Chinese Characters. He notes that Wolf Warrior 2 tells the same story about the salvation of Africa, ‘an Africa again flattened to a horror image of war, disease, and poverty but also occasionally blessed by idyllic nature and strolling lions.’ He also argues that in every scene, there are recurring images that reproduce exactly ‘the same stereotypes and tropes seen in Hollywood hero films, except now a Chinese man carries out the mission usually assigned to a white hero’ (Xiang, 2018).

Some scholars focus on Wolf Warrior 2’s implications about China’s domestic and foreign affairs. Huang (2017) labels the film patriotic for its theme of punishing those who offend China. He notes that the film’s success rests in its ‘unabashedly patriotic tone, perhaps best captured by its tagline’: “Whoever attacks China will be killed no matter how far the target is.” The expression is a slight adaptation of an ancient military general’s vow to his emperor, made during the Western Han dynasty (206 BC–9 AD), to defeat foreign invaders in the north (Huang, 2017). Film critic Jonathan Landreth views the film as having delivered ‘China’s best-yet imitation of the flag-waving, chest-thumping nationalist action film that Hollywood has churned out for decades, spinning a tale of military supremacy, do-or-die bravado and exceptional moral rectitude’ (Landreth, 2017). On the other hand, Tom Harper, in his essay in The Conversation, considers Wolf Warrior 2 as both a critique of Western foreign policy and an expression of Sino-African solidarity, ‘ties which stretch back to the period of post-war decolonization – when the nascent People’s Republic of China provided assistance to numerous independence movements in the continent fighting against exploitation and harsh colonial policies (Harper, 2017).’ Following commencement of the flow of aid to Africa after the Asian-African Conference held in Bandung in 1955, China continued providing aid to the independence movements even after most African countries succeeded in gaining independence. This was to consolidate independence and ensure that the emerging African nations thrived. The Tanzania-Zambia Railway (TAZARA), constructed in the 1970s, is considered an important symbol of the support of African governments emerging from national liberation movements (Stahl, 2016). It connected Zambia to the port of Dar es Salaam in Tanzania, thereby eliminating Zambia’s economic dependence on the apartheid regimes of South Africa and Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) (Stahl, 2016). In 1989 China began hosting delegations from liberation organisations and simultaneously began exploring the possibility of renewed economic ties with an independent South Africa. In preceding decades China and the Soviet Union had been locked in rivalry over patronage of South African liberation movements (News24, 2017).

Anti-African racism in the film industry

Anti-African racist stereotypes in the film industry have their roots in the colonial relationship between Africa and the West. As with colonial politics, education and literature, the invention of motion pictures led to presentation of the African story from the colonizers’ point of view. Africa in the film industry was (and has largely remained) synonymous with evil, backwardness, underdevelopment, disease and death.

In 1986, Sydney Pollack’s Out of Africa, a film adapted from Danish author Karen Blixen’s racist memoir, ‘won a Best Picture Oscar for basically depicting a glamorous three-hour version of the white colonial fantasy of Africa’ (Orubo, 2017). But this was neither the beginning nor the end. A lot of films have gone on to gain popularity globally with their one-dimensional narratives. Films such as The African Queen, George of the Jungle, Coming to America, Blood Diamond and several others have all presented single-sided narratives with brutalizing images of Africa.

In the documentary Africa’s Narrative: Hollywood vs. Africa, Nigerian filmmaker Olu Yomi Ososanya observes that ‘Hollywood has a homogenous narrative of Africa which does not represent a continent of 54 countries, numerous tribes and ethnicities’ (Orubo, 2017). He notes that while war, famine and child soldiers are not all false, the narrative is anything but singular. Such colonial tropes appear even in the 2018 blockbuster Black Panther, in spite of the film’s eagerness to invoke a progressive Pan-African aesthetic (Zeleza, 2018). For example, Zeleza notes that ‘while portraits of an urban skyline are latched on to aerial overviews of Wakanda, much of the action in the film, save for the technological center where Sheri works, takes place in the countryside under the cascading river falls and the savanna grasslands of traditional portraits of Africa.’ Gathara (2018) makes a similar observation, noting that the movie trots out many of the same destructive myths about Africans that circulate the globe.

In general, the racist stereotypes that characterize Hollywood and the Western film industry have thrived on the politics of colonialism/neo-colonialism and imperialism. The industry continues to prey on the psyche of unsuspecting cinemagoers, who with time, internalize such negative images of Africa and begin to view Africa from that single perspective. However, with the rise of criticism and Africa’s current postcolonial state, the racist stereotypes have become more subtle. The celebration of the White Saviour Complex and other related neo-colonial tropes has ceased to be as open as it once was.

Infantilization of Africa

Throughout Wolf Warrior 2, Africans are depicted as a childish people perpetually in need of a saviour to guide them. The concept of infantilization manifests itself in several scenarios in the film, the most blatant being the relationship between Leng Feng and Tundu as godfather and son. Tundu looks up to his godfather for everything, from moral uprightness, to security, to filial relations. Infantilization in the film traverses gender and class, as it likewise manifests in the relationship between Tundu’s mother and Leng Feng, Dr. Smith and Pasha, the rebels and Western mercenaries, the African locals and Chinese heroes at the Hanbond Chinese Factory, and Dr. Chen’s significance as emphasized in the film’s exposition.

In spite of his age, Tundu sells pirated porn discs. His mother knows and much later, aboard the Chinese warship, she warns him not to sell his pirated porn to the Chinese – a conversation that casts her in a dubious light. After all, in an earlier scene where the boy tried to sell porn to Feng, the godfather expressed moral concern, and warned Tundu that he would tell his mother, casting the discs away. Feng’s actions are in sharp contrast with those of Tundu’s mother, who only shows concern over the morality of her son when she advises him (Tundu) over his dealings with the Chinese.

The infantilization of Africa intensifies with the reassertion of colonial prejudice against Africans, specifically as an intellectually inept and primitive people whose lives revolve around trivia. Throughout the film, the African characters appear to be no more than good dancers and imbibers of liquor. The best that can be said of Wolf Warrior 2’s African characters is that they possess kinetic intelligence, as evidenced by the beach soccer and intra-match muscle displays, though even here, the Chinese hero comes out better than the locals. The portrayal of Africans as childish, stupid, and devoid of intellect finally bursts any semblance of subtlety in the film’s climax when a veteran Chinese ex-military ‘hero’ observes: ‘Our African friends, it doesn’t matter if it is war, disease or poverty, once they are around a bonfire all their cares go away.’ The message is clear: Africans are hollow in the head and heart – nothing beyond fun matters to them. In the film, Africans are infantilized. This is probably why the government of the nameless African country appears to be ‘totally incompetent (the typical trope of the failed African state)’ (Rofel, 2018). When one mercenary asks, ‘Why are we helping these fucking idiots?’ the response from Big Daddy is simply, ‘Welcome to Africa.’ In essence, the scene reasserts the notion of infantilized Africans, who are lacking in knowledge and intelligence. As observed by Patrick Gathara in his essay “Black Panther offers a regressive, neocolonial vision of Africa,” Wolf Warrior 2’s main character battles American mercenaries in a war-and-disease-ravaged Africa filled with infantilized, dying Africans. ‘This is familiar territory that Hollywood has traversed for many decades with titles such as Out of Africa and The Constant Gardener’ (Gathara, 2018).

|

Big Daddy and his team of mercenaries |

Liu (2018) makes an interesting observation: almost all the African characters in the film are unnamed, relegating their characterization to insignificance. However, he notes that the few who are given significant characterization and names are women and children (Tundu, Tundu’s mother Nessa, and Pasha). This ‘produces an image of Africa as feminized, infantilized, and racially subjugated in a state of permanent emergency in need of a Chinese hero’ (Liu, 2018), who comes in the form of Leng Feng and the other three main Chinese characters. Meanwhile, the antagonist – a leading mercenary who commits atrocities against these overly infantilized characters – is a male, white character named Big Daddy. The name – Big Daddy – and the infantilization compounded by the feminization of the African characters is not sheer coincidence. These choices all point to a view of Africa based on prejudice and narrow perceptions of the continent’s social, economic and political wellbeing.

The ‘Heart of Darkness’

Wolf Warrior 2’s denigration of African people, particularly in its plot and characterization, is likely familiar to any cinemagoer or close reader of Western literature on Africa from both colonial and postcolonial times, some of which has faced criticism for its negative representation of the continent. Dire poverty, starvation, disease and war form an ensemble of attributes that defines Africa. Africa is a damned place, its 1.2 billion people are, as Binyavanga Wainaina satirizes on colonial, parochial depictions of Africa, ‘too busy starving and dying and warring and emigrating’ (Wainaina, 2006), so that nobody really cares whether they should have names in a film set in their own backyard, exploring experiences of suffering and encounters with ‘new saviours.’ The difference this time is, as noted by many critics of the film, that the degradation is coming from an otherwise longtime comrade-in-arms in the Global South.

The rebels in the film do not have a cause, or if they do, it is designed to be overshadowed by a combination of idiocy and ruthlessness in their killing sprees. Although they post revolutionary slogans in the streets leading to a Chinese embassy compound, there is nothing that substantiates their actions. They are trigger-happy savages with no mission other than to loot and kill. Wolf Warrior 2 appears to be about demonstrating to the world (again) that Africa is a land filled with wicked hearts, reminiscent of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. It is a narrative that depicts a lack of value for human life on the continent.

In this ‘Heart of Darkness,’ war, death and disease plague the society. When the narrative around Leng Feng shifts to Africa, we are introduced to a disease-ridden continent through a woman selling herbs to Leng Feng. To coax him into buying the herbs, she advertises them as having saved the lives of four people when an unnamed outbreak wiped out an entire unnamed village.

The goal is to create an impression of Africa as a place of suffering – and nothing else – among the audience from the very beginning of the film. We experience the climax of this suffering when, escaping from the Chinese-funded St. Francis Hospital, Leng Feng, Dr. Smith and Pasha encounter victims of the Lamanlha virus. They are immediately surrounded by living victims, who are covered in sores and move like zombies. These dying people are only looking for food, which the three distribute, after which they leave behind an applauding crowd that moments earlier was an army of zombies. For these unnamed characters, there is no other description as befitting as Joseph Conrad’s, when through authorial violence, he presented impressions of the African characters in his Heart of Darkness as ‘nothing but black shadows of disease and starvation, lying confusedly in the greenish gloom.’

A homogenous wild ‘country’

Another image that prevails in Wolf Warrior 2 is that of Africa as a homogenous whole, a wild country teeming with animals. The setting of the film in a nameless African country is directly linked to the notion of uniform representation when it comes to Africa. That is, the setting can be anywhere in Africa, and the experience will be the same because, purportedly, Africa is one country. It is a single, undifferentiated entity – a characterization that recurs in global media discourses about Africa.

When Leng Feng, Dr. Smith and Pasha set out from St. Francis Hospital through the quarantined Lamanlha zones on their way to the Chinese factory, they drive through natural terrain punctuated by a big river and grasslands. They are in the middle of a valley, and a few meters from where the car has stopped, four lions are feeding on a zebra. The scene seems to exist as a means of exalting the beautiful scenery and wildlife that has typically been associated with Africa. Alternatively, the scene is included simply to complete the image: it is not Africa until one encounters wildlife and forests.

The image of wild Africa is underscored by the young Chinese security officer at the factory, Leng Feng’s destination. The office (also a home) is decorated with photos, paintings and sculptures of wild animals. Upon Leng Feng’s arrival, the film momentarily shifts its focus to the young man touching a crocodile sculpture. There is also a sculpture of a white fox, which he prides in having shot during his stay in the wild jungles of Africa.

As Zimmerman (2014) argues, though there might be millions of Africans who have been scarred by war, poverty, and disease, Africa is not just the sum of its human misery, any more than it is one huge animal safari that must be exploited to reassert cinematic stereotypes. This is, however, exactly the story in Wolf Warrior 2.

Redefining the White Saviour Complex

The last critical issue worth noting in Wolf Warrior 2’s representation of Africa is that the continent is portrayed as a battleground, where a real superpower is judged by its interventionist military and economic projects. While trying to show that China is replacing the West in terms of importance and impact on the continent, the film recreates the White Saviour Complex, this time embodied by China.

In several instances the film presents the Chinese as the new saviour of Africa, redefining the White Saviour Complex. Firstly, it is a Chinese doctor, Dr. Chen, who invents the antidote for the Lamanhla virus – a crucial plot element in the film. This antidote survives the exploits of Leng Feng, who arrives just in time to save it via Dr. Smith. In turn, it is Dr. Smith, a Chinese American, who administers the antidote’s first trial on Leng Feng, a Chinese superhero, who caught the virus while working for a good cause. Moreover, the only hospital in the film, St. Francis, is funded by the Chinese.

|

Dr. Rachael Smith at the Chinese-funded St. Francis Hospital |

In addition to the health-related narrative trajectories, the redefinition of the White Saviour Complex specifically for China manifests itself in the portrayal of Chinese foreign policy, as well as in the respect China commands in the nameless African country. For example, at the height of all the madness, it is at the sight of a Chinese flag in situations where there is a significant Chinese presence that the rebels halt fighting – with the exception of the action at the Hanbond Factory where most of the action in the film takes place. The statement ‘It’s the Chinese’ recurs unnecessarily every time the fighting is about to be halted. Furthermore, with the exception of China, every other country has abandoned this Africa that is so in need of a saviour. The American embassy cannot help, even after its citizen, Dr. Smith, uses Twitter to contact them, depicting a lack of seriousness, or even disinterest in African affairs, in American foreign policy. Likewise, all Western ships are shown sailing off the coast of this unnamed country while the Chinese alone come in. The Chinese abide by international law and no matter how provoked, they wait for the United Nations to authorize them to commence strikes against the rebels before taking action.

Lastly, China’s saviour complex is depicted through the economic conditions of this war-torn country. The only significant industry shown in Wolf Warrior 2 is Chinese-owned, the factory where most of the action later takes place. The only shop to which the film pays any attention is owned by a Chinese businessman. The small-scale business transactions that occur at the film’s onset largely involve Leng Feng, the Chinese hero. The totality of all these elements in the film presents an image of a China that is on course to replace the West as Africa’s saviour on all fronts. This representation fits well with the situation in contemporary Sino-Africa relations in which China has emerged as a dominant force in its engagement with various sectors on the continent. On the military front, China has increased its operations in Africa. For example, China’s first and only overseas military base is in Djibouti. In recent years, Chinese military personnel have also taken part in UN missions in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Liberia, Mali and South Sudan (Zheng, 2017). In infrastructure, Chinese enterprises play a leading role in the construction of railways, dams, hydropower, and other basic infrastructure projects such as public housing, hospitals, roads and stadiums. This Chinese penetration of the African market has been spearheaded by Chinese state-owned construction, telecommunication and energy companies (Marafa, 2009). Further, the continent now hosts over one million Chinese immigrants (Su, 2017). In its attempt to depict this reality however, Wolf Warrior 2 extends the neocolonial prejudices of the White Saviour Complex, which has long characterized Western film.

Generalizability?

Is the portrayal of Africa in Wolf Warrior 2 representative of stereotypes of Africa in Chinese cinema in general? What does Wolf Warrior 2 mean to Africa and its perception of China? What does the film mean to the Chinese audience?

In early 2018, China’s most watched show on CCTV during the Lunar Year celebrations (viewed by over 800 million people) sparked an outcry from the African community over its deployment of racist characterization and themes. ‘The show had a skit set in Kenya featuring a Chinese actress in blackface and fake massive buttocks, African actors in monkey costumes and hordes of other grateful blacks gushing: “I love China!” (Gathara, 2018). Interestingly, some of the critics of the spring gala’s show were Chinese netizens, expressing shame and outrage at the racist stereotypes the show portrayed (Solomon, 2018). This could indicate that although racial bigotry exists in Chinese cinema, it is not necessarily representative of Chinese society. Africa is a continent that, contrary to the film industry’s favoured tropes, has always been a lively and humane place, with its own burning challenges like any other part of the world.

It is an open secret that the Wolf Warrior 2 is an attempt at imbuing China’s film industry with patriotism. Pierrepont (2017) notes that while director Wu dismisses the criticism of Wolf Warrior 2 as nationalist propaganda, he admits that the film is ‘a combination of a commercial action movie and a Chinese military propaganda movie.’ In a news conference in 2017, Wu angrily retorted, ‘Why is that a problem? America makes movies that promote the American spirit. Why can’t I do that for China?’ (Pierrepont, 2017). Wu might have a point about Hollywood, but is that an excuse for the misrepresentation of Africa, which distorts the actual conditions by implying that the conflict and deadly disease found in some countries were emblematic of the entire continent?

Although discourses on African stereotypes in Chinese cinema might not be as charged as they are in Hollywood film criticism, Wolf Warrior 2 creates an atmosphere that encourages similar reflections. The film’s implications are dangerous. Its persistent depiction of Africa as a tattered place – a depiction that has long dominated Western film narratives – suggests that some sectors of the Chinese film industry hold the same stereotypes about the continent.

Conclusion

To sum up, Wolf Warrior 2 generally reiterates tropes from Western colonial narratives misrepresenting Africa. This article notes that although the focus might have been a patriotic appeal to the domestic Chinese audience, negative images of Africa mar the film’s African appeal. Nevertheless, the gross misrepresentation of African stereotypes constitutes a deeply negative element. The majority of Chinese people encounter Africa only through such motion pictures as well as the local media. Though patriotic and nationalistic themes might most readily resonate with the domestic audience, the negative images of Africa are simultaneously poised to take root. Wolf Warrior 2 also fails to create a credible impression of egalitarian Sino-African relations, largely due to its infantilization of Africa and its adoption of the White Saviour Complex transplanted to Chinese heroes. From the critics’ perspectives, these elements cast ambiguity on the status of existing relations between China and Africa. But to an African viewer, there is no such ambivalence. The relationship portrayed in the film is parasitic, one in which Africa is in constant need of Chinese aid. The film does not point to any egalitarianism in Sino-African relations. In light of the Chinese domestic audience’s preferences, the film’s success is unsurprising. But in Africa, there is a different response to the film: Wolf Warrior 2 is the rebirth of the colonial narrative of Africa, or rather its translation into a Chinese milieu, as the ‘Heart of Darkness.’

References

Adichie, C. N. (2009, October 6). The Danger of a Single Story. TED TALK.

Amar, P. (2018). “Thank you, Godfather:” Love and Rejuvenation, Mercenaries and Biomedicine Forge Africa and China into One Family in Wolf Warrior II. In P. Liu, & L. Rofel (Eds.), Wolf Warrior II: The Rise of China and Gender/Sexual Politics. Ohio, USA: MCLC Resource Center Publication. Retrieved on August 8, 2018 from http://u.osu.edu/mclc/online-series/liu-rofel/.

Cain, R. (2017, August 27). China’s ‘Wolf Warrior 2’ Becomes 2nd Film In History To Reach $800M In A Single Territory. Forbes.

China Daily. (2017, 08 17). Hit movie ‘Wolf Warrior 2’ puts Africa in center of tourist map. China Daily.

ChinaFilmInsider. (2017, November 22). Headlines from China: ‘Wolf Warrior 2’ and ‘Youth’ have no luck to be released in Taiwan. ChinaFilmInsider.

Chow, V. (2017, September 21). Why China’s ‘Wolf Warrior II’ is enjoying surprising success in Hong Kong. Variety.

Gathara, P. (2018, February 26). ‘Black Panther’ offers a regressive, neocolonial vision of Africa. The Washington Post.

Harper, T. (2017, August 24). How ‘Chollywood’ blockbuster Wolf Warriors 2 echoes changes in China’s foreign policy. The Conversation.

Hiu, M. C. (2018). On Wolf Warrior 2: Thoughts from Africa. JOMEC.

Hsu, K. F. (2017, September 11). Wolf Warrior 2 – see this film and you’ll finally understand China. Financial Review.

Huang, Z. (2017). China’s answer to Rambo is about punishing those who offend China—and it’s killing it in theaters. Quartz Africa.

Kuo, L. (2017). China’s Wolf Warriors 2 in ‘war-ravaged Africa’ gives the White Savior complex a whole new meaning. Quartz Africa.

Landreth, J. (2017, August 13). Film Review: ‘Wolf Warriors II’. China Film Insider.

Liu, P. (2018). Women and Children First—Jingoism, Ambivalence, and Crisis of Masculinity in Wolf Warrior II. In P. Liu, & L. Rofel (Eds.), Wolf Warrior II: The Rise of China and Gender/Sexual Politics. Ohio, USA: MCLC Resource Center Publication. Retrieved on August 8, 2018 from http://u.osu.edu/mclc/online-series/liu-rofel/.

Madrid-Morales, D. (2018). China’s media struggles to overcome stereotypes of Africa. The Conversation.

Mambrol, N. (2017). Ambivalence in Post-colonialism. Literariness.

Marafa, L. M. (2009). Africa’s Business and Development Relationship: Seeking Moral and Capital Values of the Last Economic Frontier. Stockholm: GML Print.

News24. (2017, November 1). #Declassified: Apartheid Profits – China’s support for apartheid revealed. News24.

Orubo, D. (2017). Has Hollywood’s Representation Of Africa Gotten Any Better? http://www.konbini.com/ng/entertainment/cinema/has-hollywoods-representation-of-africa-gotten-any-better/.

Phillips, T. (2017, September 24). China finds its own Top Gun and Rambo in wave of patriotic movies. The Guardian.

Pierrepont, J. (2017, August 17). Wolf Warrior II howls in Hollywood. China Daily.

Rofel, L. (2018). The Said and Unsaid of the New Worlding of China-Africa-U.S. Relations. In P. Liu, & L. Rofel (Eds.), Wolf Warrior II: The Rise of China and Gender/Sexual Politics. Ohio, USA: MCLC Resource Center Publication. Retrieved on July 28, 2018 from http://u.osu.edu/mclc/online-series/liu-rofel/.

Solomon, S. (2018, February 18). Chinese New Year Skit Sparks Backlash Over Relationship with Africa. https://www.voanews.com/a/chinese-new-year-skit-about-kenya-railway-prompts-global-backlash/4259601.html.

Stahl, A. K. (2016). China’s Relations with Sub-Saharan Africa. Istituto Affari Internazionali, 16(22), 1-29.

Su, Z. (2017, January 14). Number of Chinese immigrants in Africa rapidly increasing. China Daily.

Tartaglione, N. (2017, August 11). ‘Wolf Warrior 2’ Crosses $600M In China; No. 6 All-Time Gross In A Single Market. Deadline.

The Diplomatic Society. (2017, November 20). Action packed Wolf Warrior II. The Diplomatic Society.

The Economist. (2018, February 22). China portrays racism as a western problem. It has a problem with it too. https://www.economist.com/china/2018/02/22/china-portrays-racism-as-a-western-problem.

Viteri, M. A. (2018). China’s Emerging Global Gender Assemblages. In P. Liu, & L. Rofel (Eds.), Wolf Warrior II: The Rise of China and Gender/Sexual Politics. Ohio, USA: MCLC Resource Center Publication. Retrieved on August 8, 2018 from http://u.osu.edu/mclc/online-series/liu-rofel/.

Wainaina, B. (2006). How to Write About Africa. Granta, 92: The View from Africa.

Xiang, Z. (2018). Toxic Masculinity with Chinese Characteristics. In P. Liu, & L. Rofel (Eds.), Wolf Warrior II: The Rise of China and Gender/Sexual Politics. Ohio, USA: MCLC Resource Center Publication. Retrieved on August 6, 2018 from http://u.osu.edu/mclc/online-series/liu-rofel/.

Zeleza, P. T. (2018, March 31). Black Panther and the Persistence of the Colonial Gaze. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/black-panther-persistence-colonial-gaze-paul-tiyambe-zeleza.

Zheng, S. (2017, September 29). China completes registration of 8,000-strong UN peacekeeping force, defence ministry says. South China Morning Post.

Zimmerman, J. (2014, July 9). Americans Think Africa Is One Big Wild Animal Reserve. The New Republic.