It has long been a goal of the Chinese leadership to see the national currency, the yuan, play a greater role in international finance. The internationalization of the yuan has been pursued through many initiatives and strategies, most recently in relation to the IMF and the inclusion of the yuan in a “basket” of currencies underpinning Special Drawing Rights. Internationalization has doubtless been delayed by relative non-convertibility and China’s state-run financial system, amongst other factors. As matters are liberalized on the financial front, so it becomes more credible for the yuan to play the global role that would be expected of the currency of the world’s largest trading nation, the world’s largest manufacturing nation, and the world’s second largest economy. But the year 2018 has seen a dramatic break with this SDR-focused strategy, and its replacement by a strategy that targets the oil market – the world’s largest commodity market, where trading in US dollars has been near-universal for decades.

This break involves the launch by China of a new oil futures contract on the Shanghai International Energy Exchange (INE). Launched on March 26, 2018, the Shanghai oil futures contract has met with solid market acceptance. It has already overtaken comparable oil futures offerings in both Singapore and Dubai. Of course it still lags in volume terms behind the rival Brent crude oil futures contract traded in London, and the West Texas Intermediate (WTI) oil futures traded in New York. But the very fact that it is being traded seriously by multinational commodity traders (like Glencore) and is priced in a manner that is comparable to the Brent and WTI indices, indicates that this is an initiative with the potential to bring the Chinese yuan to the core of global commodity trading activity.

This article analyzes the significance of the Chinese oil futures contract initiative, creating what is widely known as the “petroyuan”, and sets it in the framework of the broader internationalization of the yuan. It is important not to overstate the significance of this event, as the institutions supporting the US dollar as global currency are still powerful and dominant. China’s prospects have also been dented by the aggressive trade tactics launched by the Trump administration, with a clear focus on China as principal target. The issue is complicated by the re-imposition of US sanctions against Iran, and specifically against Irani oil exports to China (as discussed below). But there is a case to be made for the strategic significance of this Chinese intervention in the commodity markets. Just as the current US financial and industrial hegemony is grounded in the dollar’s exclusivity as vehicle for global oil trading, so the decisive intervention by the Chinese to create a credible alternative in oil could well have the effect of ushering in a new, multipolar world of trade, finance and industry.

The case can be made that earlier Chinese initiatives to internationalize the yuan, such as the widely debated initiative to recast the financial system based on Special Drawing Rights (SDRs), were premature in the absence of widely accepted use of the yuan in commodity trading markets. Now China has taken an apparently well-planned and executed initiative that is focused precisely on the commodity markets, and in particular on oil, the world’s largest traded commodity. The initiative is backed by the gold convertibility of the oil futures contract, creating an important safety valve. The initiative can be viewed as supported by complementary efforts to create a yuan-based trading system in the form of the Belt and Road Initiative and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. These far-sighted measures are coming together at a time when the US is focused inwards on short-term trade measures like imposing punitive tariffs on China and its allies including those in Europe, Canada and Asia, and withdrawing from the Trans Pacific Partnership. But the storm clouds created by the Trump initiatives certainly complicate the picture – particularly the re-imposition of sanctions against Iran and its oil exports.

Oil trading and oil futures

The oil market, currently estimated to be worth $14 trillion, is (as mentioned above) the world’s largest commodity market.1 The current system of oil trading in US dollars dates from an agreement reached in 1974 between the US and House of Saud of Saudi Arabia, to the effect that all purchases of oil from Saudi Arabia would be made in US dollars, and surpluses would be recycled by Saudi Arabia through US financial markets. These terms were extended to encompass all members of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) in 1975. The terms cemented the primacy of the US dollar in world currency, trade and particularly oil trade markets.

In this way the US managed to prolong its dollar hegemony beyond the decades of the post-war financial settlement, which saw the primacy of the Bretton Woods institutions the IMF and World Bank, and the move by President Nixon in 1971 to end the US dollar’s convertibility into gold. Taking the US dollar off the gold standard could well have undermined US financial hegemony – but the US-Saudi agreement to price oil purchases exclusively in US dollars saved the day. This agreement has been strictly complied with by the Saudis as well as by the Gulf states members of OPEC, and has remained the bedrock of a US dollar-centered global commodities trading system ever since – giving what has been described as the “exorbitant privilege” enjoyed by the US as operator of effectively the world’s reserve currency.2

There have been attempts to move off dollar-denominated oil trading at various times. The EU has successfully negotiated oil supply contracts denominated at least partially in Euros, and could no doubt increase the weight of these in international transactions.3 As China has risen to become the world’s largest oil importer, so its capacity to insist on oil purchases denominated in yuan (RMB) has grown. Already China-Russian oil contracts are largely denominated in yuan, while Iran, Iraq, Venezuela and Indonesia also follow this practice to varying degrees in their dealings with China and Russia.4 In September 2018 the chairman of the Iraqi-Iranian Chamber of Commerce, Yahya al-Ishaq, told the news agency Mehr that the two countries are now using their own national currencies as well as the euro in bilateral trade.5

It is widely reported that Saudi Arabia may be about to follow suit, at least for Chinese purchases of oil. This means that already a significant proportion of the global oil market is being traded in Chinese yuan with more to follow. Of course these all represent bilateral trade deals; there is no suggestion as yet that the yuan is being utilized in multilateral trading arrangements, which would represent a stronger competitive threat for the dollar.

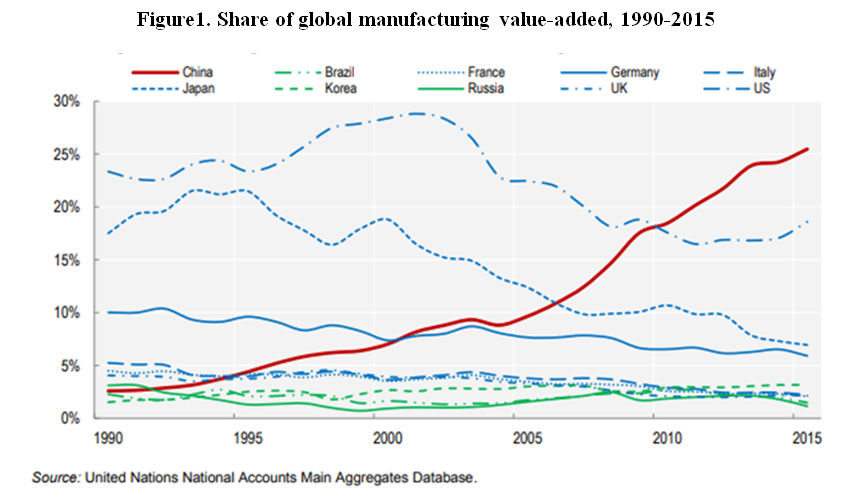

China has emerged as a significant oil trader as it moves to occupy the center of the world manufacturing system. Fig. 1 reveals how China has risen in terms of manufacturing value-added to become prime manufacturing nation by 2010, having overtaken Germany in the year 2000, Japan in 2006 and the US in 2010.6

|

The next Figure 2 reveals the complementary development whereby China has overtaken the US to become the world’s largest importer of oil as a single country.7 This makes China’s targeting of the oil market as an arena for yuan-dollar competition of strategic significance.

|

Figure 2. Chinese vs. US oil imports (million barrels per day), 2010-2017 |

As China’s significance in the global oil market grows, so its choice of oil suppliers correspondingly grows in significance. Fig. 3 reveals that Russia has now become China’s largest supplier, displacing Saudi Arabia, while Angola, Iran, Iraq and Oman remain large suppliers.8

|

Figure 3. China’s oil suppliers (by percent of total oil imports), 2016 Source: World’s Top Exports, March 2018 |

Russia, which has emerged as China’s largest oil supplier, accepts Chinese RMB (the yuan) in payment. Iran is also reported to accept yuan in payment for oil – thus evading US sanctions that came into effect at the beginning of November this year. China in August was reported to be rejecting US proposals that it curb its imports of oil from Iran – and as noted above it received a six-month waiver of sanctions due to take effect at the beginning of November.9 Angola is China’s third largest supplier – and it not only accepts yuan in payment for oil, but indeed it made the Chinese yuan its second currency in 2015, shifting firmly into China’s yuan-denominated circle of countries.10 Venezuela likewise counts itself as part of the yuan sphere, and has been accepting yuan in payment for oil supplies since 2017. These are all bilateral trading relations; they do not involve multilateral acceptance of the yuan, as yet. As these countries move into the yuan-denominated sphere, so the pressure on other countries (particularly Saudi Arabia) to accept the yuan for Chinese sales also rises – as its sales to China are sliding relative to those of other non-OPEC countries.11 In this way, a significant proportion of oil sales can be expected to be denominated in yuan rather than US dollars – possibly as early as the end of 2018.12 These direct sales in yuan are likely to be stabilized by the launch of the oil futures contract on the Shanghai INE in March this year.

The Shanghai oil futures contract

An oil futures contract is a contract that specifies a future delivery of a standard quantity of oil, of a specified quality (or grade) at a specified price. Such a contract allows both sellers and buyers to hedge against future price movements, thus ensuring certainty and stability. The futures market for oil is the bedrock of stability in the commodities markets, which underpin global industry and manufacturing.13

The oil futures contracts are specified on the Shanghai International Energy exchange (INE) in terms of their date of issue and dates within which the oil must be supplied. For example the contract SC1811 specifies a listing date as 26 March 2018, an expiration date of 31 Oct 2018, and delivery dates ranging between 1 Nov 2018 and 7 November 2018, with a benchmark price of RMB 416 for the volume of oil specified in the contract. A second example would be the contract SC1812 (meaning the contract for December 2018), where the delivery dates range from 3 December to 7 December 2018, with benchmark price also set at RMB 416.14

A recent article in the Wall Street Journal by Nathaniel Taplin indicates how fast the Shanghai oil futures contracts are being accepted by the market. Quoting Thomson Reuters as source, Taplin notes that by the end of July the Shanghai oil futures contract accounted for 14% of trades while the WTI contract traded in NY declined from 70% to 57% of trades over the same period.15 A more recent article published by Nikkei Asian Review reported that sales of Shanghai oil futures contracts by the end of September had reached 16% of all contracts issued globally, while sales of WTI standard futures fell to 52% from 60% and those of Brent crude fell from 38% to 32%.16

An initial analysis of intra-day trading patterns indicates that the volume of trades and their volatility are in line with international experience. It is also significant that the INE futures contract is the first on Chinese commodity markets to be eligible for trading by foreign players, and indeed it remains open until the early hours of the morning in China to allow for ease of trading from New York and Chicago. The same analysis of intra-day trading detected evidence of significant US trading interest.17

The launch of an oil futures contract, with full state backing as in this case, is a rare and notable event. China has waited for the best part of 25 years for this moment – ever since it launched a failed attempt to use the RMB in oil trading in the early 1990s. This early initiative failed for lack of transparency and liquidity; it was premature for China to attempt to challenge the US dollar hegemony and its centrality in financial and trade (and particularly commodities trade) transactions.

This time around China has learnt from these early mis-steps and from earlier failed initiatives by other powers – such as the attempt by Oman to launch a dollar-denominated oil futures contract from Dubai in 2007, which never attracted sufficient liquidity to claim more than a token presence in the oil trade market.

The other significant feature of the Shanghai oil futures contract is that it builds on the prior launch by Beijing of a yuan-denominated gold futures market in Hong Kong in July 2017. This ensures that oil traders can, if they wish, exchange their yuan as secured on the oil markets for gold. It is also relevant that China has been an assiduous collector of the world’s gold over the past several years. Thus the gold convertibility of the yuan-based oil futures contract is ensured.

Possible ramifications of the petroyuan

While the launching of a futures contract on the Shanghai INE might be a small step for China, it represents a giant leap for the global trading system. The key to the success of this Chinese initiative is to provide liquidity and convertibility – both of which China has been careful to provide.18 Oil traders can hedge their purchases with the oil future contract, which is denominated not just in Chinese yuan but also in underlying grades of oil that reflect Chinese trading preferences. In this way the Shanghai crude oil futures contract promises to become a global benchmark alongside the European standard in the form of Brent crude futures contract traded in London and the West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude futures contract traded in New York. Of course, this promise is being buffeted by Trump trade sanctions, against both China and Iran and Russia, and this complicates the emergence of the petroyuan, possibly halting its rise or derailing it.

The launch of the futures contract can be anticipated to widen the scope for yuan-denominated trading, both in oil and in other commodities. As more of China’s oil import bill comes to be priced in yuan, so foreign suppliers will have more yuan-denominated accounts with which they can purchase both Chinese goods and Chinese services, but also Chinese government securities and bonds, thus strengthening the Chinese capital markets and promoting the internationalization of the yuan – or at least the progressive de-dollarization of the oil market. The launch of the futures contract means that countries selling oil to China will be accumulating billions of Chinese yuan which they will then be looking to recycle back to China through purchases of Chinese goods and technologies or purchases of Chinese government bonds, thus strengthening the yuan as an international reserve currency. It can be anticipated that this will lead other countries wishing to engage in yuan-denominated trade, and for other commodity markets after oil becoming subject to similar trends. In this way, the launch of the Shanghai futures oil contract and its acceptance by the market could actively contribute to the internationalization of the yuan, and the further rise of China in the global financial system. These are points brought out in the investors’ report issued by Union Bank of Switzerland (UBS) in April 2018, after the launch of the Shanghai oil futures contract.19

.

The rise (and longevity) of the petrodollar

The emergent strategy of pricing a new oil futures contract in yuan is a smart move by China in that it seeks to recapitulate the steps that led the US dollar to its current position of dominance in foreign currency markets. As outlined by scholars such as Barry Eichengreen and Eric Helleiner the US dollar rose to prominence quite rapidly in the early 20th century, and its position was consolidated at the Bretton Woods conference of 1944, designed to lay out the post-war financial order.20 At this conference the choice was between an international unit of account (the bancor, favoured by Keynes and Britain) and the US dollar tied to gold. The US won that debate, and the dollar remained tied to gold until the 1970s when enormous US balance of payments deficits put the dollar under great stress and countries started to insist on redeeming their dollar holdings in gold. This put a strain on US gold reserves until Nixon broke the dollar-gold nexus in 1971.

It was only with the US-Saudi agreement of the early 1970s that Saudi oil sales would all be denominated in US dollars, in exchange for US guarantees to provide armaments and underwrite Saudi security, that the dollar came to occupy a genuinely central role in world commodities trade. The US was in the fortunate position following 1974 that it could pay the new high prices for oil (provoked by the OPEC cartel) in its own currency, while other countries making oil purchases would have to do so in dollars. These countries therefore faced the challenge of building their own dollar reserves, while excess dollars in the system (the so-called “petrodollars”) were recycled back to the US (as well as other markets) where they were used to buy US goods or to purchase US government securities (treasuries). This in turn increased demand for the securities and so reduced interest rates. These have been the factors that have underpinned US dollar hegemony for the past four decades following the 1974 US-Saudi agreement.

The precise steps in this process that allowed the US dollar to continue its Bretton Woods dominance even after the severing of the dollar-gold link by Nixon in 1971 (“closing the gold window”) can be traced as follows. In 1975, the member states of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) announced their decision to invoice oil sales to all customers in US dollars.21 This momentous decision had been foreshadowed by US-Saudi agreements, in particular the setting up of the US-Saudi Joint Commission on Economic Cooperation, in 1974. These agreements were followed up by a Saudi undertaking to recycle their US dollar earnings (petrodollars) in the purchase of US Treasury bills – making Saudi Arabia the largest holder of US government debt of any of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries. As David Spiro argued in a celebrated study published in 1999, this was the real driver of the dollar’s continued hegemony, building on the fact that oil sales were to be invoiced in dollars.22 The Saudis were rewarded with prime coverage by the US security umbrella and sales of US military weapons. This basic understanding, that oil would be invoiced in US dollars by all OPEC states, for all customers, in return for coverage by the US security umbrella, endured for decades – and only started to unravel with the US invasion of Iraq in 2003 and subsequent turmoil and US wars and the establishment of military bases throughout the Middle East and Central Asia.

It was precisely the absence of a Chinese strategy to internationalize the yuan (or rather de-dollarize the international system pivoting on the oil trade) via the medium of a revamped SDR system that had earlier condemned the strategy to failure. Perhaps, as argued by Barry Eichengreen and Guangtao Xia, the revamping of SDRs as a strategy was utilized by reformers in China as a cover for liberalization of the financial system at home.23 But the more that China was forced to import oil, from the early years of the 21st century, the more the SDR-based strategy appeared unsustainable. As China emerged as the world’s largest oil importer in 2017, China’s leadership recognized the opportunity for its oil purchases to be conducted increasingly in yuan.24 This strategy, which was pursued behind closed doors and did not emerge into the open until 2018 with the launch of the Shanghai oil futures contract and direct purchases of oil in yuan by China from major suppliers like Russia, Angola and Iran, has now emerged as key to yuan internationalization. It represents a total departure from the failed strategy of internationalization via SDRs, and indeed replicates the earlier strategy of the US to place the dollar at the center of the international financial system, because of its use in oil trading, updated to the 21st century.

Internationalization of the yuan – or de-dollarization?

For the past decade China has been pursuing a strategy for internationalization of the yuan involving greater reliance on the IMF’s Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) as an alternative international reserve currency.25 The strategy was laid out in a famous essay published by People’s Bank of China governor, Zhou Xiaochuan, in 2009 (Zhou 2009). The idea was that with new allocations of SDRs to emerging industrial powers like China, the SDR could not only serve as a development tool but also as a means of international payment that would provide an alternative to the US dollar. This was in fact a long-standing policy position on the part of China, but in the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis an SDR-centered international financial system loomed as a particularly enticing prospect for China. Zhou’s 2009 essay galvanized these efforts, as he pointed to the evident weaknesses and inadequacies of the dollar-centered system (such as the impact of US deficits) and outlined the advantages of the SDR as an alternative means of international financial settlement.

Now the moves to introduce yuan-based trading in the oil markets, and possible further developments of yuan-based trade in other commodity markets, means that the US dollar faces unprecedented challenges to its hegemony and may in the near future no longer be seen as the anchor of the international monetary system. To paraphrase Eichengreen, this could be interpreted as bringing to an end the “exorbitant privilege” enjoyed by the US on account of this dollar centrality in international trade. Rather than viewing China’s moves as focused on internationalizing the yuan, it is probably safer to view them more prosaically as aimed at de-dollarization of the international system – a move long favoured by China.

The oil market initiatives this time are complemented and supported by other foreign policy initiatives, particularly the creation of a yuan-centered trading and investment system via the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). This initiative is widely viewed as one of the largest infrastructure investment projects ever launched – and as such promotes Chinese investment and financial institutions to play a more significant role on the international stage. An important Chinese aim for the BRI as well as the associated financial institutions, the BRICS New Development Bank (NDB) (to some extent) and the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), is to promote the use of the Chinese currency (yuan, or RMB) as a vehicle of trade. While it has long been a strategic goal of China to internationalize the yuan, until recently the trading volumes have worked against this, as did the limited convertibility of the RMB. Now with the BRI the conditions for internationalization are much more favorable. The countries aligned with China through the BRI form a significant monetary bloc, and are already accepting the yuan as payment for commodities supplied to China, and as means of payment for goods supplied from China. In Pakistan with its large China Pakistan Economic Corridor the yuan is already the dominant currency held by the central bank in its reserves. At the end of June 2018, the cumulative total of China’s commodity trade with countries aligned with the BRI reached the equivalent of US$5 trillion – with the yuan being the primary vehicle for this enormous trade volume.26 According to the HSBC, the BRI is likely to add an extra $2.5 trillion in new trade internationally each year.27

BRI trade and investment conducted in yuan promises to promote not only Chinese economic growth and financial clout but also its geopolitical influence and soft power while serving as a means for countries to evade US sanctions. Both Russia and Iran are selling oil to China and accepting payment in yuan, as a response to (actual and potential) sanctions imposed on these countries by the US. They also have extensive imports from China as well as other reasons for seeking strengthened ties. China also views the emergence of yuan-denominated oil contracts as a means for Chinese companies to buy oil and gas in their own currency, thereby avoiding exposure to foreign currency fluctuations.28 Given that China is now the world’s largest oil importer as well as its leading trading and manufacturing nation, these initiatives frame the emergence of a multipolar world.

Much discussion has focused on the prospects for the Euro as a currency to be traded in oil markets – so far a possibility not exploited or promoted with any vigour by the EU. But if pursued strongly the euro could well play the role of an alternative currency for invoicing of oil sales, and as such it has been explored by countries such as Iran as well as the countries of the Euroland.29 Central to this argument was the role that North Sea oil producers, Norway and the UK, could have played in such an eventuality. That opportunity has now passed. But the new contender is the yuan.

While it is premature to see the yuan displacing the US dollar anytime soon, the prospect of yuan trading in oil (and subsequently in other commodity markets) appears to be off to a strong start. There is the oil futures contract now being traded strongly on the INE in Shanghai. There is the bilateral trading in oil between China and oil suppliers, in yuan – where Russia, Iran and Venezuela are the lead countries so far. There is the gold convertibility of the yuan-based oil futures contracts. And there is the grade-specification of the futures contract that is better aligned with Asian oil consumption patterns than the existing international standards, Brent crude and WTI. Against these positive signs there are the negatives that the introduction of the yuan-denominated oil contract is now complicated by the imposition of US sanctions against Iran and Russia and by wider trade sanctions imposed by the Trump administration against China. While these could have an unexpected effect in accelerating China’s move away from the US dollar in oil trades, they could also have a decidedly negative impact if China is induced to move away from Irani oil imports. Thus the outcome is likely to be the result of conflicting forces. One reading, whose plausibility is argued in this article, is that yuan-denominated oil trading is likely to become more significant, partially displacing US dollar oil trading in one market after another. On the other hand there is much momentum behind the incumbent hegemony of the US dollar and the practice of invoicing oil sales in dollars. What can be said is that the shift from a dollar-dominated world towards a multi-polar world order is now well underway.

References

Li Wei 2017. Partners, institutions and international currencies: The international political foundations for the rise of the Renminbi, Social Sciences in China, 38 (2): 114-141.

Eichengreen, B. 2011. Exorbitant Privilege: The Rise and Fall of the Dollar. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Eichengreen, B. and Kawai, M. 2014. Issues for Renminbi internationalization: An overview, ADBI Working Paper series, 454. Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute.

Eichengreen, B. and Xia, G. 2018. China and the SDR: Financial liberalization through the back door. CIGI Papers Bo. 170. Waterloo, Ontario: Centre for International Governance Innovation.

Hammes, D. and Wills, D. 2005. Black gold: The end of Bretton Woods and the oil-price shocks of the 1970s, The Independent Review, 9 (4): 501-511.

Helleiner, E. 2008. Political determinants of international currencies: What future for the US dollar? Review of International Political Economy, 15 (3): 354-378.

Ji, Q. and Zhang D. 2018. China’s crude oil futures: Introduction and some stylized facts, Finance Research Letters, (in press).

Leverett, F. and Leverett, H.M. 2014. The birth of the Petroyuan. Sino-American currency contestation, and the international monetary system: An institutional perspective on the political economy of currency choice in international energy markets. Working paper, SSRN.

Momani, B. 2008. Gulf Cooperation Council oil exporters and the future of the dollar, New Political Economy, 13 (3): 293-314.

Noreng, O. 1999. The euro and the oil market: New challenges to the industry, Journal of Energy Finance and Development, 4: 29-68.

Spiro, D.E. 1999. The Hidden Hand of American Hegemony: Petrodollar Recycling and International Markets. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

UBS 2018. Petroyuan: The shape of things to come. UBS Asset Management (analyst Hayden Briscoe).

Zhou Xiaochuan 2009. Reform the international monetary system. BIS paper Bank for International Settlements.

Notes

This $14 trillion estimate for the size of the global oil market comes from Reuters; see “Exclusive: China taking first steps to pay for oil in yuan this year – sources”, Reuters, March 29 2018.

“Exorbitant Privilege” is the title of the scholarly work on the rise of the US dollar and its current challenges, by Eichengreen (2011). See also Leverett and Leverett (2014) for useful background on these issues from the perspective of the potential emergence of a “petroyuan”.

In October 2017 CNBC quoted Juerg Kiener, managing director and chief investment officer of asset manager Swiss Asia Capital, as saying “The U.S. coverage is dropping off. Iraq, Russia and Indonesia have all joined in non-dollar [oil] trades.”.

See “Iraq ditches the dollar in Iran trade, switches to Euro, national currencies”, Sputnik, 2 Sep 2018.

We are using manufacturing value-added as an important indicator in its own right of industrial strength and as proxy for oil demand by industry and transport. Manufacturing value-added refers to activities creating value in the country concerned. So, to take the example of the i-phone, most of the value added is provided by Japanese, Korean and Taiwanese producers of high-value components, while final assembly is carried out in China. Apple in the US appropriates most value due to its intellectual property rights and contractual arrangements.

Note that the EU combined imports more oil than either China or the US, with imports totalling 14.1 million barrels per day in 2017.

The situation regarding US sanctions against Iran complicates an already complicated situation concerning the currency involved in purchasing oil supplies. The latest situation as reported by Reuters is that the US administration has granted exemptions from US-imposed sanctions on oil exports from Iran to China and seven other countries – without mentioning the currency issue. See “U.S. renews Iran sanctions, grants oil waivers to China, seven others”, Reuters, Nov 5 2018.

See “China aims for dollar-free oil trade”, Nikkei Asian Review, by Damon Evans, September 14, 2017.

See the Exclusive report by Reuters in March this year, “China taking first steps to pay for oil in yuan this year – sources”, March 29 2018.

As outlined by Wikipedia, “Futures contract” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Futures_contract) “In finance, a futures contract (more colloquially, futures) is a standardized forward contract, a legal agreement to buy or sell something at a predetermined price at a specified time in the future, between parties not known to each other. The asset transacted is usually a commodity or financial instrument. The predetermined price the parties agree to buy and sell the asset for is known as the forward price. The specified time in the future—which is when delivery and payment occur—is known as the delivery date. Because it is a function of an underlying asset, a futures contract is a derivative product.”

See “A Chinese oil slick for the dollar?” by Nathaniel Taplin, Wall Street Journal, 18 September 2018.

For a discussion of the issues involved in Renminbi (yuan) internationalization, see Eichengreen and Kawai (2014).

The UBS report highlighted the significance of China’s move to provide a trading desk for oil futures in Shanghai. See UBS (2018), Box (p. 3).

See Spiro (1999) for details, and Hammes and Wills (2005) for an account that includes the OPEC oil price rises of the 1970s. A popular account of Spiro’s argument is given by Andrea Wong in Bloomberg in 2016, “The untold story behind Saudi Arabia’s 41-year U.S. debt secret”, Bloomberg, May 31 2016.

On China overtaking the US as oil importer in 2017, see the US Energy Information Administration.

SDRs (Special Drawing Rights) are supplementary foreign exchange reserve assets defined and maintained by the IMF. They constitute a unit of account for the IMF, and not a currency as such. The Chinese interventions of the past decade were arguably aimed at making SDRs behave more like a currency. For a clear explanation of the issues, see the Wikipedia entry.

See ‘Capital on the road: Belt and Road boosts yuan worldwide’, by Chen Tong, CGTN, 29 August 2018.

For a recent review in the context of the internationalization of the Renminbi, see Li Wei (2017).

See Noreng (1999) for a discussion of the prospects for the Euro as a currency to be used in oil trading, in competition with the US dollar.