Abstract

Stories of kamikaze pilots thinking about their loved ones while flying their last mission, or of wrecked toys and their missing owners in Hiroshima, elicit an emotional response. This essay analyses and provides examples of war-themed fan-produced videos, defining their conservatism in relation to Japanese war history, and showing how it relates to the kandō experience of fan viewing practices.

Keywords: Fan videos, war narratives, kandō conservatism

Wartime. A young boy dreams of being able to fly. He dreams of flying his Zero fighter to the front, where he fights his country’s enemies. We see a brief, touching memory of the boy’s role model, presumably his father, who also served as a pilot. We see the boy’s dogfights. In the tragic final sequence, the boy is falling toward the sea having been shot down. In his final moments he imagines wings springing from his back and flying towards the ‘sky of eternity’…

|

Kōtetsu no tori [Bird of steel] Footage: Original animation. Created by Wataame (music) and hazfirst (animation). Upload date: 22 June 2013 Access Date: 3 December 2017 |

Kōtetsu no tori [Bird of steel] is one of the many fan-produced videos on the theme of the Asia-Pacific War. Some tell a fictional story set during the war. Others are commentaries on pre-existing works of fiction or interpretations of historical events. They are made using footage from commercial movies, archival recordings, or original animation, but all can be categorized as derivative works, rooted in external narratives. The overall atmosphere of the videos is set by the music, which ranges from fight songs from game soundtracks and popular romantic ballads, to original scores written by the video creators and performed by the synthetized voices of the Vocaloid music production software.

Despite the wide variety of music genres, themes and types of footage, almost all war-themed fan productions seem to share a certain narrative core. They touch upon themes of sacrifice and bravery, heroic acts motivated by love, or narratives of civilian victimhood, especially tragic stories of children. What connects them most clearly is the creator’s goal to evoke a deep emotional response among viewers. Stories of kamikaze pilots thinking about their loved ones while flying their last mission or of wrecked toys and their missing owners in Hiroshima elicit an emotional response, which many who post comments on YouTube videos describe simply as kandō shita – they felt deeply touched and moved by what they saw on screen. These ‘moving’ narratives, which are the heart and soul of war-themed fan-produced videos, can be categorized as ‘conservative’. In this essay, I will analyse war-themed fan-produced videos, defining this conservatism in relation to Japanese war history, and how it relates to the kandō experience of fan viewing practices.

Pride, nostalgia and experiencing kandō among conservatives

Conservatives and nationalists are not monolithic groups. Different elements can be emphasized within these ideologies, like dedication to the nation-state or to the general idea of country. They prefer different forms of engagement: political, online or everyday life, as in the case of so called ‘pop nationalism’. With these differences in mind, creating a broad frame for conservative/nationalistic ideology is difficult (cf. McVeigh 2004, Penney 2008). For the purpose of this study I use the term ‘conservative’ as a person focusing on the narrative of Japanese going to war to protect their homes and their loved ones, believing that Japan was forced into the war by the circumstances. Conservatives in this sense take deep pride in acts of wartime generation. They have knowledge of Japanese wartime crimes and responsibility, but do know acknowledge it, ignoring the discourse. They also tend to emphasise Japanese victimhood. Furthermore I define ‘nationalist’ as people who actively deny Japanese war responsibility, engaging in historical revisionism. Rather than victimhood, they emphasize Japanese bravery in the fight against Western aggression and colonialism. Both definitions refer to one’s views towards war history only, not to one’s political or social engagement.

Conservatives emphasize the bravery and sacrifice of pure-spirited Japanese soldiers fighting in a lost cause and portray them as heroes. Japan is not the only country whose dominant discourses defend and romanticize a violent past. The American south has its ‘Lost Cause’ myths, presenting the Confederate struggle in the Civil War as a heroic fight for a noble cause, more about ‘state’s rights’ than slavery. Meanwhile, in the United Kingdom there is ‘Raj nostalgia’, namely a fascination with the colonial past, but without acknowledgement of its inherent violence.

This broader phenomenon of romanticizing the past is rooted in feelings of nostalgia. Purifying the past and creating a national imaginary around a heroic or romantic past is less connected to the past itself and more a response to contemporary demands and anxieties:

It is the promise to rebuild the ideal home that lies at the core of many powerful ideologies of today, tempting us to relinquish critical thinking for emotional bonding. The danger of nostalgia is that it tends to confuse the actual home and the imaginary one (Boym 2001:XVI).

Nostalgia for the long-gone, idealized past that can be juxtaposed with the shortcomings of present-day Japan is an important element of the conservative worldview and can be seen in many war-themed fan productions.

When discussing the notion of pride in the Japanese nation and its history, another important element is so-called puchi nashonarizumu, ‘pop/petit nationalism’, which is based in pop culture, national symbols, emotions rather than deeper thought, and the need to experience a sense of community. This ‘carefree’ (kuttaku ga nai) and innocent (mujaki na) patriotism resulting simply from ‘liking Japan’ has been discussed by Kayama Rika (2002), Kitada Akihiro (2005) and Rumi Sakamoto (2008). It is defined as being disconnected from political statements, but rather as seeking ‘innocent’ pride in Japan with a focus on sport, language, culture and national products. Although it involves nostalgia for the past, it is distinct from rightwing political nationalism, promoting remilitarization, historical revisionism, and hostility towards Japan’s regional neighbors.

Since the platform for fan videos is the Internet, they are also related with the phenomenon of ‘Internet rightists’ (netto uyoku), whose activities are described by Sakamoto (2011) as ‘apolitical nationalism’ and media- and image-oriented. It is hard to ascertain whether the right-wing commentators on the Japanese online forum 2–channeru engage in offline political activism, despite their prominent activity in Cyberspace, and the same can be said regarding creators of fan videos. The content they create has an element of entertainment, and even if it is conservative in tone it does not necessarily encourage real-life political involvement1.

Kitada, while discussing the emotional ‘romantic cynicism’ that is characteristic of post-modern Japanese online nationalism, explores the increasing role of kandō in Japanese television since the 1990s. Kandō literally means ‘feeling moved’ and is used to describe being deeply touched, moved or impressed by something. According to Tokaji Akihiko, kandō as an emotion is difficult to define. It is a mixture of different feelings like joy, sadness, sympathy, astonishment and respect, and is often an emotional response to a story or work of art (2003:236-237). Horie Shūji (2006:176) states that kandō is not built into any work of art by default – it is the emotion evoked in the viewer as a result of consumption of a particular work2. Kandō is strongly connected with sympathy toward a character with the viewer can positively relate.

Emotional narratives seem crucial not only for the ‘romantic cynics’ discussed by Kitada, but also for another group within conservative youth known as yankii. These young people aim for a ‘bad boy/girl’ look in fashion, put great value on ‘spirit’ (kiai) and ‘bonds’ (kizuna), and based on these care deeply about their family, friends and local environment (cf. Harada 2014, Saitō 2014). They are not invested politically, but they remain close to home, staying ‘critical towards intellect and embracing their feelings’ (Saitō 2014:146). This ‘anti-intellectual’ stance is crucial within the yankii worldview, and gives kandō experiences an important role. While they may not be active supporters of nationalistic groups or involved in national-scale politics, kandō narratives present in war-themed productions, based on sacrifice for loved ones and bonds between ‘brothers in arms’, fit into yankii affective priorities. Young people who actively seek kandō experiences can easily find them in war narratives, both in mainstream war-themed cinema productions and in fan-produced videos.

Fan productions

Fan-produced videos belong to a very broad category of fans’ cultural activity, which includes fan art, cosplay, dōjinshi (fan comics), fan fiction (derivative stories written by fans), song covers and original musical compositions referring to a certain fandom. Fan productions are a sign of an individual’s devotion to a particular fandom, but are also a means of self-expression. Marx wrote about general human production: ‘as individuals express their life, so they are. What they are, therefore, coincides with their production, both with what they produce and with how they produce’ (1970:42). Therefore, fan productions are not only a tribute towards a particular work of fiction or cultural phenomenon, but also important manifestations of creators’ views, wishes and emotions.

For young people in countries where daily access to the web is standard, the Internet is often a platform for distinctive patterns of behavior and modes of self-expression. This is especially visible in fan cultures. The importance of online networks in anime fan interactions in the United States has been analyzed by Lawrence Eng (2006). Fans discuss their interests and hobbies on dedicated websites, post pictures, comment on the creations of others and upload their own work, often remaining anonymous. Internet users often open up to others more, discuss their views more passionately and are harsher in stating opinions than in real life (cf. Suler 2004). While fan productions can be presented in various offline places, like fan conventions or dedicated shops, the Internet is where fan works are most widely available, particularly video fan productions.

I define ‘fans’ as people attached to and committed to a specific genre, work, or character (fictional, semi-fictional or historical), creator/performer or a certain form of activity, like cosplaying or using Vocaloid software. People who create war-themed fan videos can be fans of a cinematographic genre (for example, some create videos dedicated almost exclusively to various war movies), of militaria (making videos dedicated to wartime period, but also Japanese Self-Defense Forces or representation of warfare in video games) or finally of vidding (the process of making a fan video) itself, as some creators use great variety of fandoms, focusing primarily on the creative process rather than expressing devotion to a certain title or theme. Not many vidders however are dedicated fans of a single specific fandom that they exclusively use for fan video production, as a limited length of the footage (particularly in the case of a movie) consequently limits vidders’ creativity and does not provide enough material for multiple non-repetitive fan videos.

Henry Jenkins states that fans are ‘consumers who also produce, readers who also write, spectators who also participate’ (1992:208). Creativity is not a condition of being a fan (Hills 2002:30), although it is conspicuously present in many fandoms. Through their productions, fans become active creators of fan culture. Fans are inspired by commercial productions, mainly movies, but also comics, books, and even documentaries or museums. They produce their own works in the form that they feel best expresses the topic and themselves. Moreover, fan productions can be the key reason behind the growth of a particular fandom, even after the original production came to an end. Juli Stone Pitzer suggests in her work on Smallville fandom that

the visibility of fans as producers (…) can help generate fan visibility, spark enthusiasm for the series, rekindle interest among former fans, or introduce new males and females of all ages and demographics to the series by the way of contagious online fan enthusiasm’ (2011:123)

Similarly, war-themed video fan productions can capture the attention of a more random consumer of Internet media, encourage them to watch the source footage or learn more about the topic.

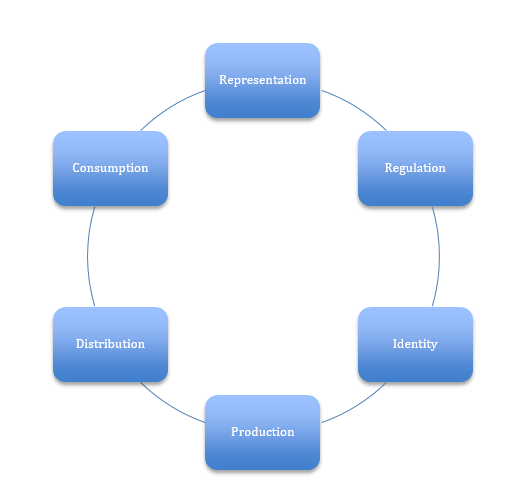

Circuit of culture – defining fan productions

Whether discussing dōjinshi, popular manga, music videos made with edited movie footage, or original Vocaloid compositions, there are features distinguishing fan works from commercial productions. Paul du Gay et al. proposed a ‘circuit of culture’ by defining five major, interrelated cultural processes that must be applied to the object of cultural study: representation, identity, production, consumption and regulation (du Gay et al. 1997:3). While I use this concept to define fan productions, I have modified it by adding a sixth process – distribution. In the two decades that have passed since du Gay et al’s work, the means of digital distribution were developed and this dramatically affected the ways in which products can be shared and distributed among users. As the major medium by which fan productions are distributed, the Internet strongly influences other elements discussed by du Gay.

|

Circuit of culture |

We may categorize fan productions as follows.

Representation – In a graphic, (audio-)visual or textual form; signifying positive engagement in a particular fandom, phenomenon or type of activity; expression of a fan’s personal commentary on and wishes for the fandom as well as a means of self-expression;

Identity – Created by fans for fans, presumably members of the same fandom or those having similar knowledge of the fandom, and not limited by nationality or geography; expressing an identity of fans as creators as well as consumers of derivative works;

Production – Following the consumption of other (commercial) goods like movies, books, songs etc.; home-made individually or by small groups; the product can be sold, but production does not provide a living income; usually produced anonymously, using a pseudonym;

Consumption – Often free of charge, via the Internet or during fan-conventions; purchase is possible via personal sale or – on limited scale – in designated shops and at events;

Regulation – Self-regulation of the community and the regulations of the distribution platform (website, event etc.);

Distribution – On the Internet on general (i.e. video-sharing) platforms or dedicated (i.e. cosplay) websites; in dedicated places for fans (i.e. specialized shops, conventions); no involvement of a third-party distributor; no promotion or advertising in mainstream/commercial media, but often recommended by other fans via forum, blogs, URL sharing etc.

Fan-produced videos as an emotional medium

Online fan-produced videos related to the Asia-Pacific War range from works reusing only third-party footage to videos created from scratch, but they all combine music and visuals. Another feature shared by these productions is the conservative view of history they are presenting. In other media formats like music, manga or cinema the whole ideological spectrum can be observed, but fan-produced videos are much more limited. While searching for war-related content among this type of video on NicoNico Dōga (a Japanese video sharing site that requires user registration) and YouTube3 I was not able to find any video conforming to my definition of fan production representing progressive views, using progressive movies, or touching upon the topic of Japanese aggression and war responsibility. What they present generally is ‘feel good’ narrative about Japanese heroism, not only involving soldiers, but also individuals like Sugihara Chiune famous for saving Jews in Lithuania where he worked at the consulate, as well as deeply moving images of suffering4.

Marshall McLuhan stated that ‘”the medium is the message” because it is the medium that shapes and controls the scale and form of human association and action’ (1964:9). This assertion may be debatable when considered across the whole of war-related media production, but for war-related fan productions, it seems to hold true and fan videos almost by definition present conservative views of history. This form of fan activity also presents much more conservative war-related content than war-related fan art, where narrative emotionality is certainly harder to achieve.

An explanation of this phenomenon can at least partially be found in Stuart Fischoff’s study:

When an emotionally powerful visual track is combined with an emotionally expressive soundtrack, the heightening of affective meanings achieves an intensity that can produce a physiological response in spectators. (…) In this way, a well-conceived soundtrack can make an otherwise weak scene into a powerful emotional event (2005:19).

Fan-produced videos often use footage that was originally emotional: kamikaze farewells, the struggles of civilians, and so on. The ultimate goal of creators is emphasizing the emotionality of these scenes with precise editing and fitting music. Music is a medium for expressing and evoking emotions, and particularly important for young people as a means of self-expression (cf. Wells and Hakanen 1991). Some empirical experiments (cf. Sirius and Clark 1994, Ellis and Simons 2005) have shown that the combination of audio and visuals affects viewers more than these elements separately, creating a synergetic relationship in terms of emotional response. Consequently, by combining visuals with a well-chosen music score, creators of fan videos can give their work a stronger emotional appeal than the already emotional visuals did on their own.

Song lyrics also add to the emotive nature. Whether it is a song composed by someone else or the creator’s original composition, fan-creators usually choose songs with music and lyrics both fitting the overall tone of their work. Lyrics, therefore, become an additional commentary to the video content or tell a whole new story in original compositions. The importance of lyrics is shown by the effort of many creators to include them in the video as subtitles, especially in the case of Vocaloid compositions, because the original lyrics cannot be checked by the audience elsewhere. Kandō, which is present in most fan-produced videos, and especially Vocaloid compositions, supports the idealized image of Japan’s past, but remains largely free of hate speech and political involvement characteristic of the activities of nationalist groups.

Fanvids (MADs)

Montages of third party-content video and music, broadly called fan videos (hereafter ‘fanvids’), are known in Japan as MADs (Myūjikku Anime Dōga). MADs are mainly uploaded on NicoNico Dōga, but they can also be found on YouTube. This makes videos easily accessible for viewers, with some reaching hundreds of thousands of views. Fanvid creators, known as vidders, use material from live action movies and TV-shows, animations, video games, manga, graphics, photographs and documentaries. Creators edit video footage and combine it with the music of their choice. Although instrumentals or Western music are also used sometimes, the hits of Japanese pop and rock bands, anime and video game soundtracks are more popular. Coppa (2008) argues that ‘fannish vidders use music in order to comment on or analyze a set of preexisting visuals, to stage a reading, or occasionally to use the footage to tell new stories’. In fanvids music is used as an interpretative tool to enhance the visuals and give them a new context.

Before discussing Asia-Pacific related MADs specifically, it must be mentioned that wartime events and aesthetics are vividly present in Japanese popular culture and used broadly by fans, even though they are not necessarily presented in historical context. Recent popular franchises such as Axis Powers Hetalia, Kantai Collection and Strike Witches5 have spawned fandoms actively producing derivative works. They do not present the war in a historically accurate way, but still make a connection to wartime events on an aesthetic level (using uniforms and weapons), via content (using names and maps), and emotionally (presenting touching sequences of characters’ deaths during battles). Such titles inspire fans’ creativity in form of MADs, fan art or dōjinshi presenting variety of genres, including comedy, action, romance and drama. Even though focused on the adventures of cute characters, fans become familiar with some historical aspects of war as well6 (Fig.2).

|

Wartime navy vessels personified as young girls (Kantai Collection) |

MADs related directly to the Asia-Pacific War can be divided into three basic types based on the footage they use.

The first is a ‘tribute’ to a fictional work, whether a movie, manga, or TV-show, usually containing footage only from one specific production. After watching or reading a particular work, fans decide to edit it as a way of expressing their engagement and appreciation. Works that have generated fandoms and extensive vidder activity can be identified by browsing YouTube. They include animations such as Hotaru no haka [Grave of the fireflies] and Za Kokupitto [The Cockpit], and the movies Otokotachi no Yamato [Yamato], Eien no Zero [Eternal Zero] and Merdeka 17805. War-themed fanvids can be found by searching particular tags naming fandoms or groups (like kamikaze), but also accidentally while looking for MADs to a certain song or by clicking on related videos suggested by YouTube or NicoNico Dōga. MADs can therefore help viewers to discover new fandoms and present new content to them.

The songs used in MADs do not need to be thematically related to the movies. It can obtain new meaning because of the scenes it is associated with. One such case is the song Omoide yo arigatō [Thank you, memories] performed by enka artist Shimazu Aya and written by Aku Yū. While searching for this song on YouTube in November 2017, the two most popular search results are war-related fanvids and several others can be found further down among the search results. This song was first used in a war context by a user named AYACHANNEL100 in May 2013 in a kamikaze-themed video. Similar to many other enka ballads Omoide yo arigatō has a nostalgic tone. The persona evoked by the lyrics gives thanks for everything he/she experienced in life, including all the pain and suffering, but most of all love. When set in the war context the song makes it seem as if soldiers (pilots) were ready to die for the greater cause, having accepted their fate after having lived and loved with their whole hearts. In Video 2 Omoide yo arigatō was set to the 2005 movie Otokotachi no Yamato, evoking deep sympathy for soldiers leaving their loved ones behind:

|

Omoide yo arigatō (Otokotachi no Yamato) Shimazu Aya cover by akinoitigo [Thank you memories (Yamato) Shimazu Aya cover by akinoitigo] Footage: Otokotachi no Yamato [Yamato] Created by akinoichigo Upload date: 6 February 2015 Access Date: 3 December 2017 |

MADs in many cases present the storylines of the original productions and repeat their messages. Nevertheless, vidders still filter the original work through their own perceptions. Itō Mizuko (2012) argues in the case of AMVs (anime music videos) that:

Like fan fiction and fan art AMVs appropriate and reframe found materials, engaging in a critical practice of connoisseurship and interpretation by creating an incredibly diverse range of media works. In many cases, fan-created transformative works give voice to marginalized subjectivities and viewpoints and offer alternative interpretations of popular text (Itō 2012:287-288).

Consequently, the same movie can become source footage for multiple fanvids expressing different emotions, depending mostly on the impression the vidder had after watching the original and what aspects of the original production they want to emphasize.

This becomes clear when comparing sentimental Video 2 with Video 3, set to a song Asu e no hōkō by JAM Project, originally the theme song of the erotic PC game Muv-Luv Alternativ. It became very popular among creators of action-MADs and was used in several war-themed fanvids, including Otokotachi no Yamato:

|

Otokotachi no Yamato x Asu e no hōkō (Hiroimono) Footage: Otokotachi no Yamato [Yamato] Created by 96multi1007 Upload date: 2 July 2014 Access Date: 3 December 2017 |

The combination of video and song presents a strongly conservative narrative of Japanese sailors sacrificing themselves for the sake of their loved ones and building a happy, peaceful future through their heroic acts. The viewers can feel pride in the soldiers’ bravery and cheer for and support their fight.

Consequently, via their music choice and editing, the vidders have emphasized different aspects of the movie Otokotachi no Yamato and created videos eliciting different emotions: one is sadness and nostalgia, another is pride, respect and admiration towards sailors. Still, neither of them criticizes the movie nor presents a message that contradicts the original, presenting only two different aspects of conservative views on war history.

The second category of war-related fanvids is the ‘real history’ MAD, focusing on actual historical events. Here the vidder’s inspiration comes not so much from consuming a particular work, but rather from a general interest in the topic. The ideological message is more actively shaped by the author. Creators seek out footage from various sources and can use different works of fiction centred on the theme as well as documentaries and photographs. War-themed MADs like this are often dedicated to a certain event, like aerial battles, or groups like the navy or pilots. These works are a sort of ‘nostalgic reminder’ of the idealized past, but also carry messages concerning the present, calling for gratitude towards soldiers who fought for the country and presenting them as role models for future generations.

Similarly to mainstream productions, an especially popular theme is kamikaze pilots. MADs contain recordings of their farewells and take-offs, often accompanied by quotes from kamikaze letters, which demonstrate a degree of research carried out by MAD creators. A representative example of kamikaze-tribute MAD is Video 4:

|

Kamikaze tokkōtaiintachi no isho [Last will of kamikaze unit members] Footage: Historical recordings and photographs Created by niconekoneko [NicoNico Dōga user] Uploaded by koniboshi Upload date: 7 December 2008 Access Date: 3 December 2017 |

The song suggests the type of emotion that the fanvid creator is trying to evoke among viewers. The creator chose a romantic ballad Kimi ga tame, performed by Suara, which originally featured in the shōnen (targeting young males as audience) anime series Utawarerumono. The song is yet another nostalgic composition about missing a lover, but when combined with kamikaze images it can be understood as a farewell message from people heading to their deaths. Lyrics such as ‘If you’ll remember serenity, I will be there’ and ‘People will rot away someday, but they will become a song to be passed down through the ages’ emphasise the pilots’ sacrifice and encourage viewers to feel sadness and sympathy for the young pilots.

The videos are rooted deeply in the literary genre of hōganbiiki (‘sympathy for a tragic hero’), which emphasizes ‘the nobility of sacrifice to a losing cause’ and evokes an ‘aura of sentimentality around tales of futile suffering’, giving meaning to the deaths of young people in the war and remembering them with ‘a kind of self-indulgent pathos’ (Orr 2001:11-12). What is emphasized in the videos is the purity of the soldiers’ spirit and the pride felt in their patriotism and precious sacrifice, which are arguments characterizing the attitudes of Japanese conservatives (Seaton 2007:25).

Although fanvids are not regulated from the top down, they present considerably less message diversity than Japanese mainstream productions. Vidding, rather than a forum for intellectual reflection, is a hobby-activity resulting from emotional investment in original content. Since it is done for entertainment, without a clear political activism aspect, it comes as no big surprise that ‘feel good/moved’ narrative wins over ‘war responsibility reconsideration’ content. Seaton (2007:140) suggested that conservative war-themed publications have higher ‘enjoyment level’ and can be widely read for leisure, while progressive ones are ‘educational’. The use of conservative narratives may therefore in many cases result from ‘attraction to emotion’ rather than to the narrative itself.

Although I have focused on ‘tribute’ or ‘real history’ fanvids, mention of yet another, more distinctive and directly political use of war references in MADs is necessary to complete the picture. War history is often present in videos which are actually an ‘ideological manifesto’ of right-wing nationalists.

A creative example of such an ‘ideological manifesto video’ is a variation on the opening of the anime Shingeki no Kyōjin [Attack on Titan]. This extremely popular anime premiered in 2013 and tells a story of humanity on the verge of being wiped out by giant creatures called ‘Titans’. The survivors live behind huge walls and struggle to survive Titan attacks. A user called suidajapan created a MAD called Shingeki no Mikuni [Attack on Japan], inspired by the opening sequence of Shingeki no Kyōjin. The video was removed from YouTube in May 2018, but because of its importance for the discussion, as well as popularity (it received almost 250,000 views before removal), I will briefly discussed its historical representation.

Referring to the original storyline, the creator substituted ‘Japan’ for ‘humanity’ and ‘white people’ for ‘Titans’. Suidajapan presents the struggle of the human Japanese Empire representing humanity, against the Titan Western powers, depicted as monstrous creatures, while also portraying other Asian countries as an obstacle to Japan regaining its pride as a country Through their hostile policies, other countries make it difficult for Japan to recover pride in the past and the Imperial Line, to restore its army, and to express patriotism in Yasukuni Shrine. The video includes footage of kamikaze pilots, Imperial Army soldiers, Zero fighters, and pictures of Yasukuni Shrine – the controversial Shinto shrine devoted to the war dead that helps to propagate ultra-nationalist war narratives. By referring in form and content to one of the most popular recent anime, Shingeki no Mikuni is easily stumbled upon by unsuspecting users looking for a different type of ‘fan’ content than that related to Japanese nationalism.

Videos actively promoting nationalistic ideology can focus on war history or just refer to it to evoke patriotic feelings and comment on present issues. Both historical and contemporary ‘real life’ video footage is used, usually combined with lengthy on-screen text presenting the authors’ political and ideological views. Internet right-wingers (netto uyoku) are active users of video sharing sites. While NicoNico Dōga is known as a strongly conservative environment, YouTube as an open access international platform should give a chance for more varied ideological content. Yet, even on YouTube progressive content (like SEALDs (Student Educational Action for Liberal Democracy) promotional videos) has rather negative ratings, while conservative and nationalistic videos are voted upon favorably. Also the fact that nationalistic videos depicting war history massively outnumber this type of video depicting Japan’s war responsibility confirms the trend noticed a decade ago by Takahara Motoaki that the Internet is drifting right (2006:90).

Creating nationalistic ideological manifestos in the form of MADs can reflect a nationalistic worldview, but feeling touched by a conservative movie and making an emotionally corresponding MAD arguably does not. Therefore, the third category is clearly related to nationalism and rightist views that are rooted in intellectual involvement in the topic. The first two types of MAD can be seen instead as representative of ‘petit nationalism’, based on vivid emotions and emotional reaction towards certain conservative narratives, as presented in the fanvids.

Vocaloid compositions

Fan creations are not limited to remixes of preexisting media. Many creators produce original compositions using Vocaloid, a singing voice synthesizer into which the user inputs original lyrics and melodies, creating their own songs that are performed by digital idols. The most popular voices are personified by cute manga-style humanoid figures, for example Hatsune Miku, a girl famous for her now iconic blue-green ponytails (Fig. 3). Miku has become much more than a software character. She is a Japanese ‘star’ with a big fan base who went on her first world tour in 2016 performing ‘live’ (as a hologram) in Taiwan and in the US.

|

Hatsune Miku. |

Synthesized songs accompanied by visuals are uploaded as videos to video sharing platforms. Vocaloid songs and videos vary in terms of quality. Some are produced by advanced users and accompanied by professional-quality original animations, while others are made by less experienced users and have a simple still background with the lyrics. This variety is reflected in the number of views. Some songs attract only a few hundred views, while the most popular get tens of millions. Considering the wide popularity of Vocaloid music it is not surprising that there are some war-related songs. Vocaloids can be used to create both covers of existing songs and original songs. I will focus on the latter, although Hiroshima-themed songs and wartime gunka (military songs) are often covered with Vocaloid software.

In contrast to vidders, Vocaloid composers create their works from scratch, without reusing third-party footage. Three main topics seem to inspire Vocaloid creators.

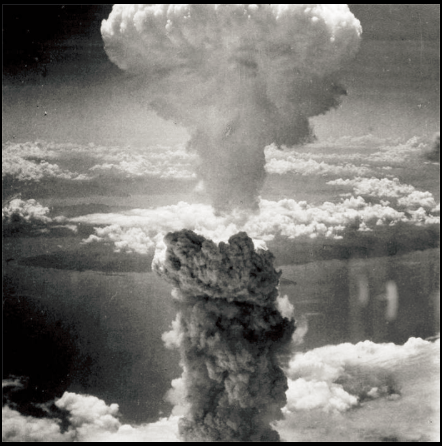

The most popular is probably the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. While vidders do not seem keen on using footage from fictional or documentary works depicting the nuclear bombings, these events have encouraged great creativity among Vocaloid composers. However, while these compositions are numerous, they are typically far less popular and their view numbers are limited to a few thousand. Numerous compositions depict the morning when the A-bomb fell on Hiroshima (Nagasaki receives considerably less attention) and the aftermath of the explosion. Some describe the events in a lyrical, poetic way; some have original perspectives beyond the new music, such as Video 6, which is about a stray cat wandering around the destroyed city; and others describe victims’ suffering and the effects of radiation with very graphic images. Many of the songs were originally uploaded to NicoNico Dōga at the end of July and beginning of August, around the bombing anniversaries. These compositions are far from nationalistic glorification of war heroes, but embody the feeling of kandō by presenting civilian suffering. Created as tributes to Japanese victimhood, they also present an anti-war statement. As John Dower wrote:

Hiroshima and Nagasaki became icons of Japanese suffering—perverse national treasures, of a sort, capable of fixating Japanese memory of the war on what had happened to Japan and simultaneously blotting out recollection of the Japanese victimization of others. Remembering Hiroshima and Nagasaki, that is, easily became a way of forgetting Nanking, Bataan, the Burma-Siam railway, Manila, and the countless Japanese atrocities these and other place names signified to non-Japanese (2014:144).

Pacifistic views are shared by both Japanese presenting progressive as well as conservative views towards history. Nationalists, on the other hand, tend to reject pacifism, believing in strong, remilitarized country. The current political right aims at the country’s remilitarization and supports the idea of sacrifice for the state and development of nuclear weapons (cf. Penney 2012). Consequently, many conservatives (in the sense of views on war history) taking pride in the national past are not supporting contemporary conservative politics. The views of conservative online fan creators cannot be easily equated with those espoused by right-wing pundits and politicians.

|

[Hatsune Miku] Noraneko no uta Nyao Hiroshima [Hiroshima no ano sangeki no nichiji wo oshiete kudasai] [(Hatsune Miku) Stray cat’s song Meow Hiroshima (Please tell me about this tragic time of Hiroshima)] Footage: Historical photographs [Another version of the video available with Hatsune Miku singing and dancing] Created by qunta pon Upload date: 26 July 2015 Access Date: 3 December 2017 |

The second major theme that Vocaloid composers address is kamikaze sacrifice. Kamikaze-themed compositions tend to reflect the common representations discussed above. Vocaloid users often present the tragic fate of brave kamikaze pilots in the form of a short story, often involving the trope of lovers separated by death. This standardized narrative reflects mainstream kamikaze-themed productions, a genre that became significant from the middle of the 1950s to 1970s. Pacifistic in tone, these movies explored volunteer sacrifice and the meaning of brotherhood (Standish 2005:184), and introduced female characters mainly to emphasize soldiers’ sacrifice (2005:194). The genre became prominent again in the 2000s with several highly successful productions, particularly Hotaru [The Firefly, 2001], Ore wa, kimi no tame ni koso shini ni iku [For those we love, 2007], and Eien no Zero [Eternal Zero, 2013]. These kamikaze movies are still characterized by standardized, highly emotional narratives of love, loss and sacrifice. Even if mainstream productions are not numerous, they provide popular material for vidders and vivid inspiration for Vocaloid composers, who reflect the narratives and emotions present in mainstream productions in their own works. A popular example of such content is Video 6 created by Team Kamiuta, a successful Vocaloid creator group that got so popular over time that now publishes its own CDs, sells songs on iTunes, and even has some songs available in karaoke boxes, despite all the songs and videos being available for free on the Internet8. As such, the group’s activities fit into the framework of fan production, as do most Vocaloid (and all MAD) works. Contrary to many fan art and dōjinshi creators, most Vocaloid composers are not aspiring professionals, but primarily ‘fans’, which gives them relatively large creative freedom and makes self-expression more important than commercial breakout.

|

[Nekomura Iroha & VY2 ] Jikon no yōyō kono keikō ni ari/The Glow Enveloped Boundless Future Footage: original animation Created by Kamiuta and Matsuura (music), hazfirst (animation) Uploaded by: Nekomura’s Helmet Upload date: 4 November 2014 Access Date: 3 December 2017 |

Members of Team Kamiuta seem to have a particular interest in war history, since they have produced at least one more war-themed song, dedicated to the battleship Yamato (Video 7). Stories in both videos clearly evoke nationalist symbols like the Rising Sun Flag. A major visual difference can be found between these videos and Video 1 (Kōtetsu no tori), since the latter does not include any clear national markings like flags or hachimaki headbands, and even national markings are missing from the Zero fighters9. Despite the conservative tone and form, a representative of Team Kamiuta told the author that rather than offering viewers a particular ideological message, his goal was to encourage a general interest in the war, which is supposed to result in further personal research. When asked about the criticism the video faced (especially from Koreans) on NicoNico and YouTube, the creator explained that these critical voices can inform Japanese viewers about the past, so disabling comments on the videos would deprive viewers of a chance to learn about other perspectives on war history. He also added that everyone is entitled to their own opinion regarding the video (Ueda 2014). Despite this statement, many comments below the video simply describe the tears the song brought to the viewers’ eyes and the kandō they experienced, while other comments form part of heated ideological debates and include abusive language. In the case of Team Kamiuta there is a gap between the creator’s intentions, as explained to this researcher, and the majority of interpretations of the narrative presented in the compositions. However, the descriptions of other war-themed Vocaloid compositions on NicoNico Dōga seen by the author suggest that some composers clearly meant to spread the idea of eternal gratefulness towards fallen war heroes via their songs.

|

Kochira Yamato, anata ni tsugu/Chiimu Kamiuta [Here is Yamato, sending a message/ Team Kamiuta] Footage: original animation Created by Team Kamiuta Upload date: 7 April 2015 Access Date: 3 December 2017 |

Finally, some Vocaloid compositions depict the horrors of war, but only with a vague and general reference to World War II or Japan. They emphasize how harmful war is both for civilians and for soldiers. The fate of soldiers was presented by the group Artificial Monochrome in Video 9 1/60000000, where 60 million refers to the number of people killed in World War II. The music video combines archival footage from the European front with animation of Hatsune Miku fighting as a soldier. As the creators explained to the author, they aimed at presenting the fate of one particular soldier during World War II, but instead of using a ‘nameless face’ they decided to use Miku, a character to which many viewers feel immediate attachment (Yaijiro 2014). Many viewers feel deeply moved by her tragic fate presented on screen. These videos are far from war glorification, indeed, they present war as harmful on many levels. There is little focus on particular nations, and as such these videos go beyond national perspective and are rooted in an emotional condemnation of war. The lack of national perspective distances them from national ideological stances on war history, but focuses instead on a universal anti-war message.

|

Hatsune Miku, Megurine Luka】 「1/60000000」 ~English Subbed~ 【Vocaloid PV】 Footage: original animation Created by Artificial Monochrome (Happaku and Detchi) Uploaded by Kanannon’s channel Upload date: 13 April 2010 Access Date: 3 December 2017 |

Composers use pop cultural references like the character Hatsune Miku and general manga-style esthetics to catch the attention of the average young, entertainment-seeking user of video-sharing platforms and direct their interest towards historical issues the creators value as important. Even though there are no limits to the themes the composers could choose, the most popular ones – the A-bomb, kamikaze and general tragedy of war – reflect issues that are discussed in Japanese mainstream media and in commercial productions. In this sense, Vocaloid compositions also can be seen as derivative works, although not belonging to a particular fandom, but broadly rooted in Japanese cultural memory.

‘To make them think…’

I reached out to twelve creators, three vidders and nine Vocaloid creators, to ask about their reasons for producing the videos. Where an e-mail address was available, I contacted them via e-mail. For other creators, I left messages on video uploading sites. I received five replies, all from Vocaloid users. Four of them explained the background of their activities in e-mail correspondence and one agreed to a Skype interview. While vidders expressing the nationalistic views in their works did not reply, the answers given by Vocaloid creators offer important insights into their motivations as creators who develop war-themed works and share them online. For Ken Tamayan, creator of Video 9, Boku wa kakuheiki da (No more hibakusha), the greatest inspiration was the 1982 American documentary The Atomic Café, made using archival material from the 1940s to 1960s. The positive nuclear propaganda of the era and early American optimism concerning atomic bombs shocked Tamayan, especially in light of the horrific results of the bombing he had learned about while visiting sites in Hiroshima. In his work he aimed to raise awareness of the consequences of nuclear war and to prevent American-style ‘nuclear enthusiasm’ (Tamayan 2014).

|

Boku wa kakuheiki da (No more hibakusha) [I am a nuclear weapon (No more hibakusha)] Created by Ken Tamayan. Upload date: 6 August 2009. Access Date: 3 December 2017 |

Yajiro, who wrote the lyrics for 1/60000000 (Video 8), mentioned reading a book that reported that World War II took the lives of 2% of the global population. This figure combined with her grandparents’ stories about friends and relatives who died during the war made her realize the scale of the human tragedy, and she wanted to share this realization with others (Yajiro 2014). Ueda from Team Kamiuta (Videos 6 and 7), meanwhile, was mostly inspired by the war experiences his grandmother shared with him (Ueda 2014). Finally, Takemaru, the author of the most clearly conservative Vocaloid composition discussed in this paper (Video 10), said his inspiration was rooted in his political interests in relation to the Great East Asia War (Daitōa sensō). This name for the conflict was used in Japan during the war and nowadays is typically used only by rightwing nationalists. He wanted to share Japanese history as he sees it in the form that he feels best at producing – Vocaloid composition. Takemaru believes that the meaning of kamikaze sacrifice was to save Japan’s honour, and that despite losing the war, Japanese can always be proud of having such heroes among their ancestors (Takemaru 2016). Ueda (Video 6) and Takemaru (Video 10) created similar kamikaze-themed songs, but when asked about the background of their works, the former was open to discussing Japanese war responsibility while the latter reiterated nationalistic premises. However, this difference is not visible just by watching their works.

|

[VOCALOID Original] Yakusoku no oka – Tokkōtai ni sasageru uta – KAMIKAZE [Promised land – song dedicated to kamikaze] Footage: original animation and historical recordings Created by Takemaru Upload date: 11 February 2015 Access Date: 3 December 2017 |

Despite these various sources of inspiration, the goal of all these people was basically the same: they wanted to make viewers think about certain issues in a certain way. They got interested and emotionally involved in a historical issue, and decided to create their own representations of the past to make the audience think (kangaesaseru) about matters they believe are not discussed enough. This point was developed most by Ueda, who claimed that the Vocaloid format and uploads to NicoNico Dōga are perfect for his purposes, since he wants to spread awareness of war mainly among young people. They have the most limited knowledge of the past, and Vocaloid compositions can generate discussion and a desire to learn more about the topic.

It is hard to judge viewer reactions based solely on comments left under the videos. Still, a survey of available statements suggests that in many cases war-themed works made audiences feel rather than think. Comments about kandō and shedding tears are numerous in almost all war-themed fan produced videos. But, comments are also diverse. After Video 1 viewers left diverse comments varying from gratefulness towards Japanese soldiers fallen during the war through appreciation of peace to necessity of teaching Japanese youth war issues such as the comfort women and other crimes. As Ueda’s work shows, creators’ intentions are not always clearly visible in their works, and the reception also varies. With the lyrics in Japanese and given the historical setting, it can also be assumed that most viewers are Japanese, but comments were written also in Korean, Chinese and English, and a few works (especially those emphasizing pacifist messages) were subtitled in English, suggesting an international audience. Comments not in Japanese often expressed critical opinions on war history and stoked debate in the comments section.

However, rather than the war itself, what is seen in many videos is nostalgia for an era of pure-hearted heroes or a society where people were devoted to certain ideas and ready to sacrifice everything for it. This longing for heroism and high values is visible in many video fan productions, especially those with a kamikaze theme. This was articulated by Takemaru, who asked rhetorically, ‘How many of today’s Japanese live fully (isshōkenmei)? Haven’t many of them lost the spiritual virtues of the war generation?’ (Takemaru 2016).

Another element of consumption of these videos is the raw numbers of people watching them. The table presents the total number of views from YouTube and NicoNico Dōga for videos discussed in this paper:

|

The videos vary greatly in terms of access rates. MADs using more popular songs or Vocaloid compositions created by already popular groups have more chance of being discovered by viewers. Still, the raw data indicates that the most popular war-themed videos can gain millions of views. Creators enjoy differing levels of popularity, but vidders and Vocaloid composers clearly have a voice that cannot be ignored.

Conclusions

Both MADs and Vocaloid compositions are created non-commercially at home with computer software by individuals or small groups. Both forms rely heavily on music and are distributed mainly via the Internet. They remain an online phenomenon and are not directly related to ‘real-life’ political activism of their creators. War-related content is generated as a hobby following the consumption of other media. MADs are derivative works which remix elements of mainstream productions and Vocaloid songs are fans’ original compositions. MADs result from affection for a particular work, express fascination with a specific aspect of romanticized war history, and use both war and pop culture references to express certain ideological (often nationalistic) messages with the aim of spreading those views among viewers. Vocaloid videos, both the music and visuals, are made from scratch by fans, but they still reflect what their creators consume as users of mainstream popular culture and the views that were presented to them by family and society.

Although the Internet gives creators anonymity and freedom of expression, most fan-produced videos vary in tone from conservative to nationalistic. Combining music and visuals, these videos are a highly emotional form, created as an entertaining activity by fans sharing their own ‘feel good/feel moved’ experience. These feelings are strongly related to conservative narratives of sacrifice and victimhood. Deep emotions evoked by these narratives can often be summarized in one word, kandō. The videos present a past one can be proud of, and role models one can follow. In this way, kandō can be perceived as a tool for promoting conservative ideology rooted in the imagined past.

By sharing romanticized visions of the past via fan productions, some Japanese young people create an emotionally involved community touched by the semi-fictionalized past they share. Historical accuracy is far from the main issue here, emotional responses are given priority. However, reaching for conservative war discourse should not be treated as clear proof of nationalistic ideology and conservative political engagement among all video creators, as their intentions can be less obvious than the videos themselves seem to suggest. Most remain remote from political involvement, despite shared nostalgia for the past. Young people express through kandō narratives a yearning for pride in history, but also for peace. They also express a dedication to friends and family that motivates the soldiers in the works more than devotion to the state – central in conservative political discourse. This element is inconsistent with nationalistic or right-wing rhetoric. War-themed video fan productions reveal the relationship between an emotional kandō experience, nostalgia and conservatism. An idealized past that touches the viewer is also a past that viewers can take pride in, precisely what Abe Shinzo and other conservative politicians have sought to normalize.

Related articles

Noriko Manabe, Uprising: Music, youth, and protest against the policies of the Abe Shinzō government. The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus Vol 12, Issue 32 No 3, August 11, 2014.

Rumi Sakamoto, ‘Koreans, Go Home!’ Internet Nationalism in Contemporary Japan as a Digitally Mediated Subculture, The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 9, Issue 10 No 2, March 7, 2011.

Rumi Sakamoto, “Will you go to war? Or will you stop being Japanese?” Nationalism and History in Kobayashi Yoshinori’s Sensoron, The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 6, Issue 1, January 1, 2008.

Sven Saaler, Nationalism and History in Contemporary Japan, The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 14, Issue 20 No 7, October 15, 2016.

Tomomi Yamaguchi, The “Japan Is Great!” Boom, Historical Revisionism, and the Government, The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 15, Issue 6 No 3, March 15, 2017.

References:

Boym, S., 2001. The future of nostalgia. New York: Basic Books

Coppa, F., 2008. Women, Star Trek, and the early development of fannish vidding. Transformative Works and Cultures [online]. [Accessed 19 August 2017].

Dower, J.W., 2014. Ways of Forgetting, Ways of Remembering: Japan in the Modern World. New York: The New Press.

du Gay, P., et al., 1997. Doing cultural studies: the story of the Sony Walkman. London Thousand Oaks Calif.

Ellis, R. J. and Simons, R.F., 2005. The Impact of Music on Subjective and Physiological Indices of Emotion While Viewing Films. Psychomusicology: A Journal of Research in Music Cognition, 19 (1), 2005, 15-40.

Eng, L., 2006. Otaku engagements: Subcultural appropriation of science and technology. Thesis (PhD). Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.

Fischoff, S., 2005. The Evolution of Music in Film and its Psychological Impact on Audiences [online pdf] [Accessed 19 August 2017].

Geraghty, L., 2014. Cult collectors. Nostalgia, fandom and collecting popular culture. London New York: Routledge

Harada, Y., 2014. Yankī keizai : shōhi no shuyaku shinhoshusō no shōtai. Tōkyo: Kabushiki Kaisha Gentōsha.

Hills, M., 2002. Fan cultures. London New York: Routledge

Horie, S., 2006. Sei ni okeru shinpi taiken no imi : Sono tetsugakuteki kōsatsu. Tōkyō: Sōei Shuppan, Seiunsha

Itō, M., 2012. “As Long as It’s Not Linkin Park Z”: Popularity, Distinction, and Status in the AMV Subculture. In: M. Itō, D. Okabe and I. Tsuji, eds. Fandom unbound otaku culture in a connected world. New Haven: Yale University Press, 275-298.

Jenkins, H., 1992. Textual poachers : television fans & participatory culture. New York: Routledge.

Jenkins, H. 2006. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York: New York University Press.

Kayama, R., 2002. Puchi–nashonarizumu Shokogun. Tokyo: Chuko Shinsho Rakure.

Kitada, A., 2005. Warau Nihon no ‘Nashonarizumu’. Tokyo: NHK Shuppan.

Manabe, N., 2014. Uprising: Music, youth, and protest against the policies of the Abe Shinzō government. The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus [online], 12 (32). [Accessed 11 July 2017].

Marx, K., 1970. The German Ideology. London: Lawrence and Wishart.

McLuhan, M., 1964. Understanding media: the extensions of man. New York: McGraw-Hill.

McVeigh, B., 2004. Nationalism of Japan: Managing and Mystifying Identity. Latham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Orr, J., 2001. The Victim as Hero: ideologies of peace and national identity in postwar Japan. Honolulu, Hl: University of Hawai’i Press

Penney, M. and Wakefield, B., 2008. Right Angles: Examining Accounts of Japanese Neo-nationalism. Pacific Affairs, 81(4), 537–555.

Pitzer, J.S., 2011. Vids, vlogs, and blogs: the participatory culture of Smallville’s digital fan. In: L. Geraghty, ed. The Smallville chronicles: critical essays on the television series. Lanham: Scarecrow Press, 109-128.

Saitō, T., 2014. Yankīkasuru Nihon. Tōkyo: Kadokawa

Sakamoto, R., 2008. “Will you go to war? Or will you stop being Japanese?” Nationalism and History in Kobayashi Yoshinori’s Sensoron. The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus [online], 6 (1). [Accessed 15 August 2017].

Seaton, P.A., 2007. Japan’s contested war memories: the “memory rifts” in historical consciousness of World War II. New York: Routledge.

Sirius, G. and Clark, E.F., 1994. The perception of audiovisual relationships: A preliminary study. Psycho-musicology 13, 119-132.

Standish, I.2005. A new history of Japanese cinema. A century of narrative film. New York: The Continuum International.

Suler, J., 2004. The Online Disinhibition Effect. CyberPsychology & Behavior. July, 7(3), 321-326.

Takahara, M., 2006. Fuan-gata nashonarizumu no jidai. Tokyo: Yōsensha.

Takemaru, 2016. About the creation of Yakusoku no oka – Tokkōtai ni sasageru uta[e-mail correspondence with the author].

Tamayan, K., 2014. About the creation of Boku wa kakuheiki da (No more hibakusha) [e-mail correspondence with the author].

Tokaji, A., 2003. Research for determinant factors and features of emotional responses of “kandoh” (the state of being emotionally moved). Japanese Psychological Research, 45 (4): 235– 249.

Ueda, 2014. Interview. Interviewed by the author [conversation].

Wells, A., Hakanen, E.A., 1991. The Emotional Use of Popular Music by Adolescents. Journalism & mass communication quarterly 68 (3), 445 – 454.

Yajiro, 2014. About the creation of 1/60000000. [e-mail correspondence with the author].

Notes

This is a major difference from progressive productions available on the Internet that actively contest government rhetoric and critique nationalistic arguments. Song recordings, montages from protests (cf. Manabe 2014) or parody videos created by young members of progressive movements like SEALDs or T-ns SOWL that can easily be found online, remain a distinctive form of activity from the fan productions discussed in this article. The works discussed here present entertaining content to be consumed online, while progressive activists seek to use the Internet to encourage real-life political involvement.

Still, particular plotlines and scenes have bigger chances of causing kandō among the target group of viewers. They are deliberately used by producers aiming at emotional reaction of the audience, positively influencing commercial success of the work.

I did keyword searches, looking for tags like ‘war’, ‘Asia-Pacific War’, ‘Great East Asia War’, ‘World War II’ etc. combined with ‘MAD’, ‘Vocaloid’. I also used titles of war-related Japanese movies from around the last two decades and names of popular Vocaloids. I followed related videos suggested by the sites, watched users’ playlists, using also general Google search that directed me to Yahoo!Chiebukuro pages recommending war-related productions.

Although this paper focuses on Asia-Pacific War representation in fan productions, it should be noted that “feel good” narrative within military context is not limited to past events. There are numerous, popular fanvids focused on Japanese Self-Defense Forces (JSDF), requiring separate study concerning modern military fantasy of Japanese fan creators. Emphasising dedication, heroism and sacrifice, these fanvids express and evoke pride towards Japanese forces. Despite portraying different events and era, they evoke the same kandō as war-themed video fan productions, using very similar aesthetics. Is note v missing?

Axis Powers Hetalia presents adventures of anthropomorphized countries involved in the World War II, Kantai Collection tells the story of naval warships presented as young girls, Strike Witches – of young girls combining magic and technology to defend Earth from aliens in World War II era. Published in forms of manga, anime and games, these titles gathered big and devoted fan base creating multiple derivative works.

It is especially visible in the case of Kantai Collection. Many pages are dedicated to detailed analysis of navy vessels the characters are based on, while numerous Internet discussions suggest that franchise fans developed interest in war history.

Channel of 96multi100 was closed, and original video consequently removed. The linked video is a copy uploaded by another user, with smaller number of views and more negative ratings. Re-upload of other’s users’ works is as a rule seen negatively by the vidders’ community and such copied videos are rated down.

More information about the group, including members profiles and news about current activity available here.

These decisions by creators seem not to significantly influence audience reception. In both cases viewers comment about Asia-Pacific War, soldiers’ heroic sacrifice and how moved they are by it. The message of Kōtetsu no tori seems so obvious that the audience does not comment on anything ‘missing’ from the picture, even if creators somewhat soften the conservative tone.