Abstract

In the wake of the recognition of the lack of relief measures and medical support for atomic bomb survivors (hibakusha) residing in South Korea, some Japanese dedicated themselves to assuring that Korean victims received subsidized medical treatment. This study assesses the significance of Japanese civil society-based medical support implemented by an anti-nuclear and relief organization, Kakkin Kaigi, and a Hiroshima-based doctor, Dr. Kawamura Toratarō. It also analyzes Japanese – South Korean citizen cooperation and the Japanese governmental relief program for hibakusha. In particular, it explains how Japanese grassroots movements succeeded in providing long-term medical support and eventually assuring that the Japanese government extend relief to long-neglected Korean victims.1

Key words

grassroots movement, South Korean atomic bomb victims (hibakusha), colonial period, relief measures, voluntarism, Christianity

Introduction

This article considers the plight of Korean nationals who were victims of the atomic bomb, particularly the thousands who left Japan for South Korea. In 1957, twelve years after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and Japan’s subsequent surrender, victims of the atomic bomb, but not the hundreds of thousands of firebombing victims in 64 cities across Japan, became eligible for medical benefits provided by the Japanese government. (The American government acknowledged no responsibility and provided no direct financial or other support for atomic victims.)

When the atomic bombs destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, many Korean nationals residing in the two Japanese cities were among the atomic bomb victims. According to the estimates of the Korea Atomic Bomb Victims Association (hereafter Korea Association), there were 50,000 Koreans in Hiroshima and 20,000 in Nagasaki at the time of the bombings, among whom approximately 23,000 survivors returned to the Korean peninsula following the end of the Pacific War.2 Most had migrated to Japan in large numbers following Japan’s annexation of Korea in 1910, either for work or due to forced conscription that intensified during World War II. Korean A-bomb victims developed various radiation-induced diseases in the postwar period leaving many unable to work. Consequently, they found themselves in a vicious cycle of unemployment, poverty, and diseases.3 Apart from Hiraoka Takashi’s first-hand reports about the plight of Korean hibakusha beginning in 1965, a smaller survey carried out by the Japanese Association of Citizens for the Support of Korean Atomic Bomb Victims (hereafter Association of Citizens) in 1978, which reported on 113 South Korean A-bomb survivors, also highlighted the fact that the unemployment rate among hibakusha was particularly high, since injuries from the blast as well as radiation-induced diseases prevented them from working.4 Most could not afford medical expenses in Korea and had no access to medical services. There were no support laws for the atomic bomb victims in South Korea, and awareness of the situation of the hibakusha was very low for a long time.

Meanwhile, in 1957, the Japanese government enacted the Atomic Bomb Survivors Medical Care Law, the first official measure to assist A-bomb survivors in Japan. The law guaranteed two annual health check-ups for hibakusha and the government covered medical expenses for radiation-induced diseases. The authorities issued A-bomb Certificates to those who were recognized as A-bomb survivors. At the time of its implementation, many Japanese hibakusha in the two A-bombed cities had no access to medical aid due to the initial limitation of the law, and the 1957 relief law began to be revised in 1960.5 In 1968, the Japanese government passed the Special Measures Law “to stabilize survivors’ lives and improve their welfare.”6 With these two measures, the Japanese government officially acknowledged its responsibility toward the atomic bomb victims and began to provide them with medical and financial assistance. However, these relief measures excluded Korean hibakusha then living outside Japan, specifically those in South Korea, who constituted an estimated 10% of all A-bomb sufferers. Zainichi Korean7 and other non-Japanese hibakusha residing in Japan could officially apply for A-bomb certificates. They nevertheless faced discrimination given that at least one of the two witnesses necessary for the application process had to be Japanese. Many non-Japanese hibakusha were unable to find Japanese witnesses and were therefore long unable to apply for certificates.

In the 1970s, Son Jin-doo, a South Korean hibakusha, filed a suit against the Japanese government to claim rights as an A-bomb survivor, with the support of Japanese grassroots associations. Son was the first person to take the issue of Korean (and overseas) hibakusha to court in Japan. He petitioned to have his rights as a survivor recognized by the Japanese government. His legal battle dragged on for seven years until 1978, when the Supreme Court ruled in his favor. According to the decision, “both A-bomb laws apply even to foreign [non-Japanese] citizens, provided they are hibakusha, and they are entitled to state compensation indicated by both laws.” The court held that “by ignoring these points in the case of someone who is an illegal immigrant, it means that we disregard the humanitarian nature of the laws.”8

Son’s case and the growing awareness of the existence of A-bomb victims residing outside Japan served as a sobering experience for some Japanese. In the postwar era, the prevailing view in Japan has been that the Japanese were victims of the World War II bombings, which destroyed more than sixty Japanese cities. As James J. Orr put it, “The mythicizing of war victimhood within the peace movement manifested a tendency to privilege the facts of Japanese victimhood over considerations of what occasioned that victimhood.”9 As we know, “that victimhood” was preceded by Japan’s imperial expansion in Asia. Son’s court appearance in 1970 served as an impetus for generating citizen-based movements to support the rights of Korean A-bomb survivors.

While most studies of South Korean hibakusha focus on legal cases and colonial history, there has been little discussion of the question of medical support. Medical treatment of these atomic bomb survivors was established in Japan in the early 1970s thanks to citizen-based initiatives and the formation of grassroots organizations.10 The most prominent figure providing medical support was Dr. Kawamura Toratarō, a Hiroshima doctor renowned for treating A-bomb patients. He recognized the urgency of medical assistance for hibakusha living in South Korea and called on Japanese citizens to take immediate action rather than wait for the Japanese or South Korean governments to implement relief measures. He began inviting hibakusha from the Republic of Korea to his own hospital and providing them with medical treatment at his own expense in 1973.11 Additionally, a Japanese anti-nuclear group, Kakkin Kaigi (Council for Peace and against Nuclear Weapons), played an important role in providing medical assistance for Korean victims by dispatching Japanese doctors to South Korea annually beginning in the early 1970s and setting up a medical clinic for survivors in Hapcheon in 1973.12

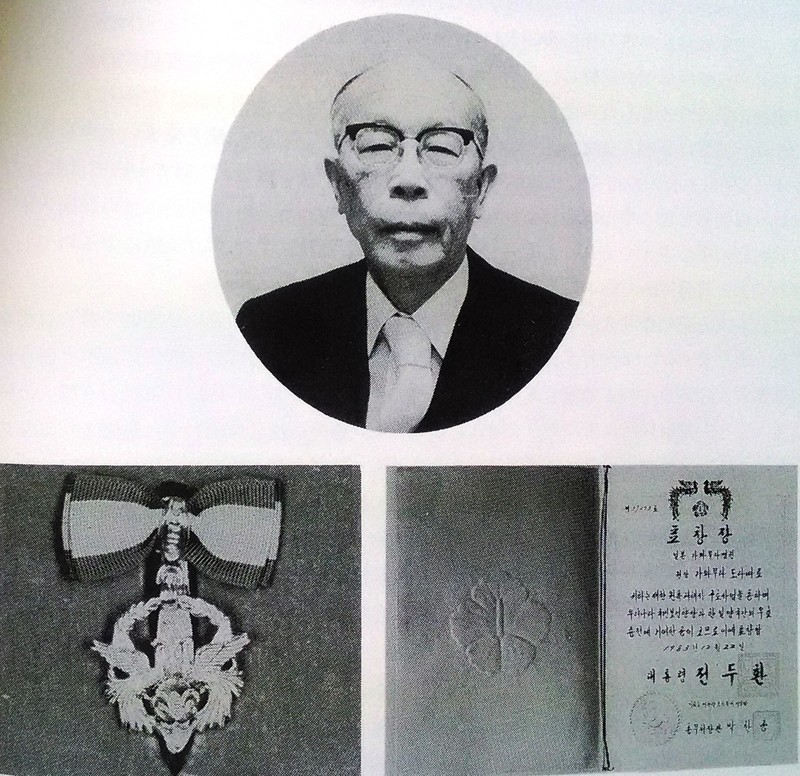

|

Dr. Kawamura Toratarō in 1984. (Source: Chūgoku Shimbun, “12 Nen Sude ni 50 Nin Chiryō,” [Providing Medical Treatment to Already 50 People in 12 Years] January 10, 1984, Box 5, HT0500600, HUA.) |

This article explores the medical assistance for Korean hibakusha who returned to South Korea, as carried out by Japanese citizens in the 1970s and 1980s, with a particular focus on Kakkin Kaigi and Kawamura’s support activities, but also touching upon the Japanese – South Korean intergovernmental relief program. The medical committee Kawamura set up in 1984 was more effective in providing support for hibakusha in South Korea than the medical support program introduced by the Japanese and South Korean governments in the 1980s.13 The grassroots medical assistance for Korean hibakusha launched in the 1970s also contributed to the Japanese Supreme Court’s 2015 landmark ruling that guaranteed reimbursement of the medical expenses of overseas hibakusha.

The case of the Japanese who provided medical assistance for A-bomb survivors living in South Korea is an example of efforts from a small number of citizens, who support the rights of colonial victims and ensure that their government, a former colonial power, faces its colonial past, and eventually acknowledges the rights of former victims.14 Instead of seeing themselves as victims of the war and the atomic bombs, as many Japanese did in the postwar era, some Japanese advocates of responsibility for Korean hibakusha emphasized Japan’s role as perpetrator, and the need to atone for its past atrocities. In the 1960s and 1970s, these advocates argued for the necessity of supporting atomic bomb victims living in South Korea.15 This article focuses on the emergence of medical support in Japan, the proponents’ views, and Japanese grassroots assistance at a time when no governmental support was available either in South Korea or in Japan for hibakusha returning to the Korean Peninsula after World War II.16

Dr. Kawamura Toratarō’s involvement in medical assistance for Korean hibakusha

Dr. Kawamura Toratarō was born on February 2, 1914 in the North Gyeongsang Province of Korea, which was then Japanese territory. His time in Korea was a key factor in his sympathy for the plight of Korean A-bomb survivors. Kawamura studied medicine at Keijō Imperial University in today’s Seoul and graduated in 1942. He lived in Korea until the end of World War II, after which he returned to Hiroshima Prefecture with his family. In July 1947, he opened an internal medicine hospital in Otemachi, very close to the hypocenter, and focused his practice on treating hibakusha (most of them Japanese).17 Reverend Kim Sin-hwan, a Christian priest working in Hiroshima, reported in his memoirs that among his zainichi Korean parishioners were many A-bomb victims. Being generally impoverished, many in the Korean community could not cover the high medical costs of treatment. However, Reverend Kim learned from his parishioners of the work of doctor Kawamura.18 In short, Kawamura had been treating some zainichi Korean hibakusha in Hiroshima before his involvement with the medical support of hibakusha residing in South Korea. Through such work, he established a reputation among the Korean community in Hiroshima.

Kawamura was unaware of the existence of A-bomb survivors in South Korea until the late 1960s. On August 1, 1968, Kakkin Kaigi organized a national assembly in Hiroshima, where Kan Moon-hee, a member of Mindan who had already been involved in Korean hibakusha support, talked about the plight of A-bomb survivors living in South Korea.19 Mindan had dispatched its first group to South Korea in May 1965 to investigate the lives of the atomic bomb survivors there, and they conducted the first survey on their health conditions and living circumstances.20 This survey raised awareness of the presence of hibakusha in South Korea, who had by then, been abandoned for two decades. It convinced both the South Korean government and later, many Japanese citizens of the need to help these former colonial victims. At the 1968 assembly, Kan Moon-hee revealed that out of the 1,700 registered members of the Korea Association in Hiroshima, 300 were in urgent need of medical treatment.21 This news shocked Kawamura. According to his son, Dr. Kawamura Yuzuru, his father had always cherished his memories of Korea. For him, South Korea was not just some foreign country; rather, it was the land where he had been born and spent his formative years. His attachments to Korea were one reason why the revelation of hibakusha living there in poverty and without treatment struck him so deeply.22

In 1971, Kawamura visited South Korea as part of the first Japanese medical delegation to examine A-bomb survivors on the peninsula. He realized that Korean victims had been excluded from the hibakusha support laws, had been unable to go to hospitals and receive treatment because of the high cost, and as a result, their situation was considerably worse than that of Japanese hibakusha. In the 1970s, the absence of an extended health insurance system in South Korea kept hibakusha from access to universal health care, which was not introduced until 1989.23 As a result, Kawamura dedicated himself to the medical support of Korean victims, inviting many patients to his hospital in the 1970s, and establishing a permanent medical committee in 1984 that brought hundreds of Korean hibakusha to Japan for medical treatment.

In the postwar period, Kawamura lamented Japan’s colonization of Korea. He concluded that the existence of Korean hibakusha was Japan’s wartime responsibility. He once told Kawamura Sumiko, his daughter-in-law, that, “I am doing this [treating Korean hibakusha] to atone for the fact that I did not understand the suffering that Koreans were enduring.”24 By providing medical support to Korean A-bomb survivors, he hoped to make amends for the crimes Japan had committed.

His medical support was widely reported not only in the local Chūgoku Shimbun, but also in national papers such as the Mainichi Shimbun and the Asahi Shimbun. In Hiroshima, Kawamura was at the forefront of drawing awareness to the Korean hibakusha’s plight, and his work helped to facilitate their inclusion in the narrative of the city’s atomic bombing – a critical first step toward their formal recognition as hibakusha. His work embodied the values of peace, aspirations for a nuclear-free world, and a lifetime devotion to providing medical treatment to atomic bomb victims. Although he was aware of Japan’s responsibility for the Korean hibakusha’s suffering, he did not explicitly criticize the Japanese government, but instead focused on their medical treatment. By inviting Korean A-bomb patients to his hospital at his own expense (beginning in the 1970s), Kawamura aimed to inspire other doctors in Japan and South Korea to follow suit, and dedicate themselves to providing medical support for hibakusha. Following his death in 1987, Dr. Kawamura Yuzuru carried on his legacy and treated Korean A-bomb patients until May 2016 in the family hospital.

|

Dr. Kawamura Toratarō received the presidential award from Chun Doo-hwan for his long-term support of Korean hibakusha in 1984. (Source: Kawamura Toratarō Ikōshū, Iryō to Shinkō, 93.) |

The beginnings of Kakkin Kaigi’s support for Korean hibakusha

Since 1968, Kakkin Kaigi has sought to generate support for South Korean hibakusha in Hiroshima. Kakkin Kaigi was established in 1961 as an anti-nuclear organization working to support both Japanese and Korean A-bomb victims.

The first major anti-nuclear movement, Gensuikyō, was formed in 1955. Most members were affiliated with the Japanese left, and their primary goal was the abolition of nuclear weapons. Due to ideological tensions within Gensuikyō and conflicting stances over the 1960 U.S. – Japan Security Treaty, members of the Liberal Democratic Party and the Socialist Party withdrew and in 1961, formed a new anti-nuclear movement, Kakkin Kaigi.25 Whereas Gensuikyo criticized U.S. possession of nuclear weapons, Kakkin Kaigi opposed possession and use of nuclear weapons by all countries. It is a nationwide organization, with its headquarters in Tokyo, and 22 branches in 38 prefectures. Through fundraising programs and membership fees, members finance activities that further their goal of completely abolishing nuclear weapons. They have appealed to governments throughout the world with the slogan: “A loving hand to hibakusha!”26

As mentioned earlier, on August 1, 1968, Kakkin Kaigi organized a national assembly in Hiroshima, where Kan Moon-hee discussed A-bomb survivors living in South Korea. This paved the way for the emergence of support movements and inspired others to aid Korean hibakusha. After learning about the existence of Korean A-bomb victims at their 1968 assembly, Kakkin Kaigi, together with Mindan, formed the Japanese – Korean Council for the Relief of Korean A-bomb Survivors in October 1968, with Murakami Tadataka as the chairperson. This was the beginning of Japanese organized support for Korean hibakusha. Their policies included advancing the issue of A-bomb Certificates for zainichi hibakusha, assisting those who had difficulties making ends meet, providing medical treatment for Korean hibakusha in Japan, issuing the medical certificate to Korean hibakusha who needed medical treatment in Japan, authorizing the entry of South Korean hibakusha into Japan for medical purposes, and establishing scientific exchange programs between Japanese and South Korean doctors to better understand the effects of radiation and its treatment.27 The council not only sought to aid Korean hibakusha residing in Japan, but also took steps to support hibakusha in South Korea.

Medical visits to South Korea

In 1968, Kakkin Kaigi, in collaboration with Mindan, emerged as the leading support movements for Korean hibakusha. Between 1968 and 1972 they sent an annual donation of one-million yen to the Korea Association. In 1971, Kakkin Kaigi dispatched a team of four doctors, who specialized in treating A-bomb related diseases, to examine the hibakusha in South Korea. One member of the team was Kawamura. Before his departure, Kawamura met Sin Yeong-soo, chairperson of the Korea Association, who came to Japan to talk about the plight of Korean hibakusha and request help and cooperation from the Japanese. Sin, like thousands of other hibakusha in South Korea, had not possessed an A-bomb Certificate and had never received medical treatment for radiation sickness. He had lost his left ear in the bombing of Hiroshima, and had visible keloid scars, the sight of which shocked Kawamura.28

Kawamura and Ishida Sada (director of the Hiroshima A-bomb Hospital Internal Medicine Department) were in South Korea from September 23 to 24, 1971, examining 60 hibakusha in Seoul.29 They then examined 65 people at Busan Evangelical Hospital.30

This visit made a powerful impression on both doctors. Ishida said, “Poverty and the high medical expenses make hibakusha even more miserable. Discrimination against them is strong, and they hold a grudge for having been abandoned for 26 years.” Kawamura found that “the first thing we have to do is to eliminate their financial burden, and it is necessary to support them from Japan so that they can have access to free medical treatment. During this visit, public opinion inside South Korea to support hibakusha started to build up, and I would like to advance such a movement in Japan, too.”31 Ishida noticed the Korean hibakusha’s dire situation, and drew attention to the discrimination they faced in their own societies upon returning to Korea. In his medical report, Kawamura stressed the need for free medical treatment, and to achieve this, he proposed the establishment of a support network in Japan and South Korea. This mission influenced his later commitment to inviting hibakusha from South Korea to Japan for medical treatment. Returning to his birthplace after 26 years, the experience of witnessing hundreds of hibakusha who had never received any medical assistance left him devastated. The Japanese medical team took important steps towards raising social awareness of the Korean hibakusha problem in both countries, laying the groundwork for a support network.

|

Baek Du-yi, 86, a Korean hibakusha in Hapcheon South Korea. |

In December 1973, Kakkin Kaigi, with the cooperation of Kawamura, established the Atomic Bomb Victims Medical Center in Hapcheon, specializing in treating A-bomb patients. The medical center was later sponsored by both the council and the South Korean government. Following its establishment, Japanese and Korean doctors began to examine hibakusha.32 It was the only facility for A-bomb survivors in South Korea until 1996. Kakkin Kaigi continued to send Japanese doctors to examine and treat hibakusha until 1995, totaling 22 visits in 25 years, and treating nearly 5,600 Korean A-bomb survivors. According to Kakkin Kaigi’s report, although this was usually a one-time medical treatment, the medical care reduced contagious diseases, internal secretions, and blood diseases among the Korean hibakusha treated by the Japanese doctors.33 Kawamura was the most active member of the medical team, participating in the first twelve visits until October 1984.34

The support provided by Kakkin Kaigi was a civil society-based assistance program, in which Japanese citizens, doctors, and hospitals cooperated to improve health conditions among Korean hibakusha. Whereas Gensuikin, Hidankyō, and other major Japanese hibakusha support groups turned a blind eye to the Korean hibakusha problem, Kakkin Kaigi was among the first peace associations to engage in supporting and bringing Korean A-bomb victims to Japanese public consciousness.

Japanese doctors invite hibakusha from South Korea to Japan for medical treatment

The visits to South Korea were a life-changing experience for Kawamura. After seeing the plight of Korean hibakusha, he gradually put his own work aside to provide medical assistance to this community.35 During his visit in 1972, Sin asked him to invite hibakusha to Japan.36 Beginning in 1972, he invited hibakusha from South Korea to his own hospital, providing for their travel and medical costs. Dr. Kawamura continued to play a significant role in Kakkin Kaigi’s annual visits to examine hibakusha in South Korea, but he invited atomic bomb victim patients to his clinic independently (he later received assistance from Christian organizations such as the Kuwana church, which helped him collect funds for bringing and treating Korean hibakusha in Hiroshima).

There was another impetus behind Kawamura’s decision to commit to the medical assistance of Korean A-bomb victims. In the 1960s, Dr. Iwamura Noboru went to Nepal to treat tuberculosis. At that time, many people from India migrated to Nepal, and the spread of various diseases, including tuberculosis, was on the rise.37 Nepal needed help to tackle this problem. The Japan Overseas Christian Medical Cooperative Service (JOCS) dispatched Iwamura who continued to work in Nepal until the early 1980s. In 1963, the Iwamura’s Supporter Association formed, a civil movement through which citizens of Hiroshima aided the Nepalese. With this, Iwamura set up a grassroots movement that connected Japan and Nepal, and channeled funds towards the Nepalese through their medical services. Kawamura was touched by Iwamura’s philanthropy and his initiatives to help the underprivileged. This, too, inspired him to provide medical support for Korean hibakusha, and to establish a similar network between Japan and South Korea.38

Kawamura was not the first or only Japanese doctor who invited South Korean hibakusha to his own hospital at his own expense. A few months before his first patient arrived in Japan, Ezaki Tetsuo, a plastic surgeon living in Tokyo, brought a hibakusha to his hospital and performed surgery to remove her keloid scars.39 In Hiroshima, too, another doctor sponsored a South Korean hibakusha’s visit to Japan to receive treatment in his hospital. This doctor was Harada Tōmin, the director of a surgical clinic in Hiroshima. In 1972, Sin told him about the dire circumstances of Korean hibakusha, and asked for Harada’s help. Then, Harada heard the first-hand experiences of the Hiroshima Paper Crane Group (Hiroshima Oriduru no Kai) members, who had been to South Korea and encountered hibakusha. Following these events, he decided to personally cover the medical treatment of Korean hibakusha, and brought the first patient to his hospital on November 13, 1973.40

As these examples illustrate, other Japanese doctors also provided Korean A-bomb survivors with medical assistance, but no one sustained such assistance for as long a period as Kawamura did. These doctors received no support from Hiroshima City or the Japanese government; they acted voluntarily. When Kawamura began providing medical support in 1973, no South Korean hibakusha – even those who had legally entered Japan and could find the necessary two Japanese witnesses – possessed the A-bomb Certificate, meaning that none were entitled to free medical treatment in Japan.41

A South Korean woman, Kim Yeong-ja was the first hibakusha invited by Kawamura to his hospital. He took this first step hoping to create a precedent, which could then encourage similar movements among Japanese doctors nationwide.42 Kim arrived in Hiroshima on March 27, 1973, and was hospitalized in the Kawamura Hospital.43 She was 31 years old, married, and had three children. However, she frequently got sick and spent eight months a year in bed.44 From that point on, he brought hibakusha from South Korea to Hiroshima regularly until 1980, when the Japanese – South Korean governmental exchange program was formally launched. Over eight years, he examined and treated 50 people.45

The Japanese – South Korean intergovernmental medical relief program and its pitfalls46

On October 8, 1980, the Japanese and South Korean governments signed an agreement to provide Korean hibakusha with medical treatment in Japan. This was the first support measure taken by the Japanese government to help its colonial victims. It was influenced by Kawamura’s individual assistance program in the 1970s, as well as by the outcome of the Son Jin-doo lawsuit.

Son Jin-doo’s legal victory at the Japanese Supreme Court in 1978, together with the expanding Japanese grassroots support network in the 1970s, marked a watershed in the Japanese government’s attitude toward Korean hibakusha. Preceding the Supreme Court ruling, whenever the Korea Association or the Association of Citizens demanded formal compensation, the Japanese government claimed that the 1965 Treaty on Basic Relations between Japan and the Republic of Korea settled all legal obligations resulting from Japan’s occupation of Korea, and insisted that South Korea had relinquished its right to demand reparation from the Japanese government.47 Nevertheless, the Supreme Court ruling in favor of Son Jin-doo brought the normalization treaty’s inadequacies to the surface, and the Japanese government took action to avoid other wartime victims filing suit and demanding reparation. The result was the medical relief program implemented with the South Korean government.

The intergovernmental medical program was scheduled to expire in 1986, and for six years, South Korea sent a limited number of hibakusha to Japan for medical examinations and hospitalization. According to the agreement, one person could stay in Japan for two months, but Japan agreed to extend the period to six months when necessary. The Japanese government covered the costs of hospitalization and health care, while the South Korean government provided travel expenses for Korean hibakusha. By dividing the expenses between the two governments, the Japanese government unambiguously indicated that this program could not be considered wartime compensation, and held onto its previous position of evading responsibility. Rather, Japan positioned itself as a benevolent nation that offered free medical treatment for Korean victims of the atomic bomb.48 The first ten Korean A-bomb survivors entered Japan to receive medical treatment on November 17, 1980.49 Japan and South Korea established this exchange program 35 years after the 1945 atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and 23 years after the enactment of the Atomic Bomb Survivors Medical Care Law. After 35 years, during which many Korean hibakusha had died, there was a ray of hope that the situation of the survivors might change.

Yet the medical exchange program with its many restrictions was far from a full-scale relief program for Korean hibakusha. At that time, the Korea Association estimated that there were nearly 15,000 hibakusha in South Korea, and the association had, nearly 9,000 registered members.50 However, only 60 hibakusha were permitted to enter Japan for medical treatment annually through this program, and their two week stay in Japan was far short of providing for full recuperation. Additionally, many elderly and seriously ill hibakusha in Korea were excluded, although they were the ones most in need of medical treatment. When the Korea Association called on Japan to increase the number of patients, Japan temporarily raised the annual number from 60 to 100, which still barely addressed the overall problem of Korean hibakusha. Moreover, once the two-month treatment period ended, some patients suffered relapses of their diseases, and needed further medical care. However, once they were back in Korea, Japan did not support their reentry or follow-up care.51

Japan and South Korea terminated the program on November 20, 1986. The South Korean government objected to its extension claiming that its national hospitals were well-equipped to treat atomic bomb sufferers, and that there were no more seriously sick patients who required treatment in Japan.52 As Michael Weiner has pointed out, “for some Korean officials, there was an element of humiliation inherent in accepting aid of this type from a former colonial power, particularly when it also highlighted the inadequacy of health provision in Korea.”53

By September 1986, 349 Korean hibakusha had received medical treatment in the A-bomb hospitals in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. As there were more than 9,000 registered members of the Korea Association, it can be concluded that the medical exchange program was ineffective in providing relief to Korean hibakusha in general.54 As Ichiba Junko put it, this was “a mere drop in the bucket.”55

Although the Japanese involved in the movements seeking recognition of Korean hibakusha have constantly demanded reparations from the Japanese government, they have never made claims on the U.S. government, which dropped the two atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. One might wonder why these Japanese activists insisted that their government provide compensation for the Korean victims of the bomb, instead of filing a suit against the country that carried out the atomic bombing and was responsible for the hibakusha’s suffering. First, some Japanese were convinced that it was their duty to advocate for the rights of the people previously victimized by their own country. Second, when signing the San Francisco Peace Treaty, Japan waived its right to demand reparations from the U.S. government in Article 14.56 Therefore, there were legal obstacles to Japan suing the U.S. government. With regard to the South Korean victims and their descendants, Takazane Yasunori confirmed that the Association of the Second Generation (nisei) Korean A-bomb Victims wished to jointly file a suit, together with members of the Japanese second generation hibakusha, against the U.S. government. However, the Japanese nisei never supported this initiative, given the legal obstacles to Japan demanding reparations.57 In August 2017, four Koreans (including first, second and third generation hibakusha) petitioned the Daegu District Court requesting mediation with the U.S. and South Korean governments, and with three U.S. companies involved in the production and dropping of the bombs (Du Pont, Boeing, and Lockheed Martin). The case was forwarded to the Seoul Central District Court, which ruled that negotiating with the United States would be difficult, and urged them to focus on the South Korean government. Eventually, the victims filed suit against the South Korean government. The outcome is yet to be announced, but if they succeed, they will move on to file against the U.S. government and companies.58 The reality is that there is little chance that the plaintiffs will win a lawsuit against the United States.

Establishing the Hiroshima Committee to Invite Korean A-bomb Survivors to Japan for Medical Treatment

Owing to the limits imposed on each patient during the intergovernmental program, there were few opportunities to return to Japan for a second treatment if their conditions worsened. For this reason, many of these patients asked Sin Yeong-soo if they could receive additional medical treatment. Sin visited Hiroshima in June 1984, and informed Kawamura about those who wished to return to Japan for a second treatment. He asked Kawamura if it was feasible to invite them once more, independent of the government program. This prompted Kawamura to set up the Committee to Invite Korean A-bomb Survivors to Japan for Medical Treatment (hereafter Hiroshima Committee) on August 2, 1984. This association provided medical treatment for hibakusha who had been in Japan for treatment, but whose disease had recurred.59

The Committee sustained itself through fundraising programs and membership fees to provide for Korean hibakusha’s medical treatment in Japan. The hospitalization of the first two hibakusha was in December 1984, and two more patients followed in March 1985.60 Kawamura had always regarded the committee as a participant in the peace and anti-war/anti-nuclear movement. It focused on medical assistance as a means to spread the message “No More Hiroshima” and “No More Hibakusha.”61

In the initial years, because of the Hiroshima Committee’s shoestring budget, only a small number of Korean hibakusha were treated in Japan, but the patients received good care, and there was no limit on their hospitalization period. The applicants could request a visa for medical treatment that lasted for 30 days, but those who wished to stay in Japan for a longer medical treatment had the opportunity to do so by having their visa renewed (the Committee assisted them in the visa renewal process, too).62 Additionally, hibakusha could apply to return for a second or third treatment to Hiroshima three years after their first treatment. The Kawamura Hospital bore the greatest burden and received 75% of the patients, but other hospitals, such as the Hiroshima Kyōritsu Hospital, the Mitajiri Hospital in Hōfu, the Nagasaki Yūai Hospital, and the Hannan Chūō Hospital, also cooperated.63

Although the Committee made great efforts to bring many Korean hibakusha to Japan to counter the limits of the intergovernmental medical program, it faced many challenges. It could only ensure medical treatment for those who possessed an A-bomb Certificate.64 Thus, Committee members faced a serious problem in finding witnesses, and applying for the certificate many years after the bombing. Furthermore, in the initial years, program participants were primarily older hibakusha who could speak Japanese, but later, A-bomb patients consisted increasingly of younger people who spoke Korean only. Interpreters thus had to be employed in the Kawamura and Kyōritsu Hospitals. Moreover, the seriously sick, those who had been most in need of medical assistance, could not make the journey to Japan, and so, could not enjoy the benefits of the program.65

The Committee continued to bring South Korean hibakusha to Japan from 1984 to 2016. Kawamura Toratarō passed away in 1987, having provided both Japanese and Korean hibakusha with medical treatment until the end of his life. Following his father’s death, Kawamura Yuzuru became the chair of the Committee. He has said that Korean hibakusha are “historical living proof” of “what the Japanese had committed in Korea in the past and the fact that Japan had shown a cold attitude [abandoned them and denied financial and medical assistance] afterwards.”66 By 2016, with the help of nearly 1,000 Committee members, 572 South Korean hibakusha had received medical treatment.67 Meanwhile, both Japan and South Korea acknowledged the Hiroshima Committee’s achievements. Reverend Kim Sin-hwan received the Kiyoshi Tanimoto Peace Prize in 1996, and eleven years later, the Committee itself received the same award.68 Additionally, as proof of their appreciation, the Korean Minister of Foreign Affairs Award was presented to the Committee in March 2015. “With this award, the Korean government recognizes the group’s efforts to bring A-bomb survivors from Korea to Hiroshima to provide medical care to them at no cost.”69

The work of the Committee over 32 years demonstrates that bi-national grassroots cooperation brought more Korean hibakusha to Japan for medical treatment than the two governments did in the 1980s. While the governmental program from 1980 to 1986 invited 349 hibakusha to Japan, the Hiroshima Committee provided medical treatment for 572 A-bomb survivors, maintaining the association for more than three decades, and using membership fees and fundraising events to cover patients’ medical fees and travel expenses. When the Japanese and South Korean governments discontinued the Korean hibakusha medical relief program in 1986, these Japanese citizens operated the only organization providing medical assistance to Korean hibakusha free of charge.70 From the 1990s, the Hiroshima Kyōritsu Hospital received many of these patients, with Dr. Maruya Hiroshi as one of the main advocates of the program.

|

Lawyers and supporters for South Koreans exposed to the atomic bombs of World War II enter the Osaka District Court on Oct. 24, 2011. The court ruled that the Osaka Prefectural Government should cover the medical costs of victims who now live outside the country just as it does for hibakusha who live in Japan. |

The Committee’s activities came to a close in May 2016. Following the landmark decision of the Supreme Court “in favor of full reimbursement of medical expenses to survivors living overseas” in September 2015, the Committee believed that it had accomplished its mission. At a press conference held in Hiroshima City on May 12, 2016, Kawamura Yuzuru said, “My father always told me that he would not be able to retire until the day the government started covering the survivors’ medical expenses. That day has finally come, and we’d like to express our gratitude to the many people who have offered their support.”71 Had it not been for Kawamura Toratarō’s determination to treat Korean hibakusha in Japan, coupled with Mindan and Kakkin Kaigi’s initiatives, hundreds of these victims might have passed away without ever receiving proper medical treatment, and likely no awareness of their difficulties would have emerged in Japan or South Korea.

Conclusion

Beginning with Son Jin-doo’s lawsuit in the early 1970s and Hiraoka Takashi’s early reports n Korean hibakusha, grassroots movements began to form around the call for atomic bomb survivors in South Korea to receive the same amount of aid from the Japanese government as their Japanese counterparts. Support within Japanese society was multilayered. New organizations were formed across Japan with the aim of providing medical, legal, emotional, and financial assistance. This article delineates the emergence of medical relief activities, and highlights the importance of activism in Japanese civil society.

Japanese supporters of the rights of hibakusha living in South Korea have also worked with zainichi Koreans. For instance, Kan Moon-hee in Mindan was a central figure in their activities. Mindan supported the first survey in South Korea in 1965, and they held a symposium in 1968, raising awareness of the Korean hibakusha’s plight. Mindan inspired Dr. Kawamura and Kakkin Kaigi to become involved in providing medical support for Korean A-bomb victims. In 1971, Kakkin Kaigi, together with Mindan, launched annual medical visits of Japanese medical experts to South Korea, where they would treat hibakusha. Additionally, Reverend Kim Sin-hwan was Kawamura’s most important aide in the 1980s, and since 1984, he has contributed significantly to the long-term operation of the Hiroshima Committee.

Medical assistance for Korean hibakusha began with Kakkin Kaigi’s dispatch of a Japanese medical team to South Korea in 1971, and this anti-nuclear organization continued sending Japanese doctors annually to examine and treat South Korean hibakusha until 1995. Kawamura Toratarō was a member of the first team of medical specialists, and later became a major advocate for providing medical assistance in Japan, specifically by inviting Korean hibakusha to his hospital at his own expense. Kawamura’s most important legacy is the citizen-based Hiroshima Committee established in 1984, which continued inviting South Korean A-bomb survivors to Japan for medical treatment until 2016. Although a small organization with a limited budget, the Committee embodied the drive among some Japanese to help Korean hibakusha. After the Japanese – South Korean intergovernmental medical relief program was terminated in 1986, the Hiroshima Committee remained the only organization still providing medical treatment for Korean hibakusha in Japanese hospitals, while receiving no funds from the national government or city authorities.72 With their continued medical support activities, they paved the way for the landmark Supreme Court decision in September 2015, which approved full reimbursement of medical expenses to overseas A-bomb survivors. Both Japan and South Korea have recognized the Committee’s effort to voluntarily treat South Korean A-bomb patients in Japan, and the fact that its long-term assistance helped to build mutual transnational support among citizens.

The Japanese government made changes in the status of Korean victims in response to the activities initiated and supported for decades by a small number of Japanese citizens. This study demonstrates that some Japanese citizens, by providing medical assistance, helped South Korean hibakusha obtain treatment for physical injuries they suffered from the atomic bombing. Additionally, it reveals how some citizens of the two countries established amicable relations at the grassroots level, which eventually influenced official policy, and resulted in a belated measure of justice for a long-neglected group of Korean hibakusha.

Related articles

- Byung-Ho Chung, Coming Home after 70 Years: Repatriation of Korean Forced Laborers from Japan and Reconciliation in East Asia

- Tessa Morris-Suzuki, Long Journey Home: A Moment of Japan-Korea Rememberance and Reconciliation

- Robert Jacobs, The Radiation That Makes People Invisible: A Global Hibakusha Perspective

Notes

The article focuses on atomic bomb survivors living in the Republic of Korea (South Korea) and does not examine hibakusha of Korean descent residing in Japan or in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea).

Ichiba Junko, Hiroshima o Mochikaetta Hitobito: “Kankoku no Hiroshima” wa Naze Umareta no ka [Those Who Brought Hiroshima Back Home: Why Did Hiroshima in Korea Come into Existence?] (Tokyo: Gaifūsha, 2000), 27. All translations have been made by the author.

The Korea Atomic Bomb Victims Association formed in 1967 after Japan claimed to have settled its wartime obligations with South Korea in the Treaty on Basic Relations between Japan and the Republic of Korea signed in 1965. The treaty failed to address the Korean hibakusha problem. The Korea Association has hibakusha members and has supported the A-bomb victims with the help of Japanese grassroots organizations since its establishment.

Hiraoka Takashi, Muen no Kaikyō: Hiroshima no Koe, Hibaku Chōsenjin no Koe [Neglected Strait: Hiroshima’s Voice, Korean Hibakusha’s Voice] (Tokyo: Kage Shobō, 1983), 26-27.

Hiraoka Takashi was a journalist at Chugoku Shimbun who delved into the history and actual conditions of South Korean hibakusha in the 1960s. He was a pioneer in reporting on Korean hibakusha-related issues from 1965 and later published books about their plight. In the 1970s, he was a key figure in Son Jin-doo’s support movement and succeeded in convincing many Japanese to assist Son’s lawsuit and advocate for the rights of Korean hibakusha. He served as the mayor of Hiroshima from 1991 to 1999.

Zaikan Hibakusha Jittai Hojū Chōsa [Supplementary Survey on the Actual Condition of Korean A-bomb Victims] (Kankoku no Hibakusha o Kyūensuru Shimin no Kai: December 10, 1978), 11. Box 1, HT0101400, Hiroshima University Archives (hereafter HUA).

For the A-bomb relief measures and their revision, see Nihon Hidankyō, “Hibakusha Taisaku no Rekishi to Genkōhō,” [History of the Hibakusha Measures and Current Laws] November 30, 2008. (accessed: November 20, 2017).

According to the first law implemented in 1957, only those victims (regardless of nationality) being in the vicinity of the hypocenter at the time of the bombing were eligible to apply for hibakusha status. This meant that Korean victims living in Japan – if they had sufficient evidence – could apply in the same way as Japanese. In 1960, hibakusha staying within two km of the hypocenter could apply for special hibakusha status and receive benefits. In 1965, people exposed to residual radiation who had entered the two cities within three days of the bombing became entitled to submit their application for A-bomb Certification. Additionally, the same revision extended the territories from the proximity of the hypocenter to some more distant areas such as Shinjo-cho, Koi, and Mitaki-machi in Hiroshima, and Narutaki-cho and Nakagawa-cho in Nagasaki. Likewise, as more areas were added, more victims exposed to the atomic bomb were recognized by the Japanese government.

Shigematsu Itsuzo, “Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Law,” in Effects of Ionizing Radiation: Atomic Bomb Survivors and Their Children (1945-1995) Leif E. Peterson, et al. (Washington, D.C.: Joseph Henry Press, 1998), 295.

Zainichi means residing in Japan, and zainichi Koreans stand for the ethnic Korean residents living in Japan. Under colonial rule, they had Japanese citizenship. During the U.S. occupation, the Japanese government deprived them of citizenship rights.

Hiraoka, Muen no Kaikyō, 149-150. Although the Supreme Court highlighted the case of illegal immigrants, not even those South Korean hibakusha who entered Japan with a legal visa were issued A-bomb certificates by the Japanese authorities between 1965 (signing of the Japan-Korea Normalization Treaty) and 1974 (Son Jin-doo’s first legal victory at the Fukuoka District Court). Sin Yeong-soo was the first who was given the certificate in July 1974. Before the District Court recognized the rights of overseas hibakusha in 1974, the Japanese authorities had rejected Lim Bok-sun’s and Uhm Bun-yeon’s application for A-bomb Certificates in December 1968, despite their possessing a valid visa upon entering Japan.

James J. Orr, The Victim as Hero: Ideologies of Peace and National Identity in Postwar Japan (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2001), 3.

There are several reasons why Japanese grassroots movements to support Korean hibakusha occurred more than a decade after the implementation of the A-bomb Survivors Medical Care Law. First, it was extremely difficult for Korean hibakusha to come to Japan legally with a valid visa due to the lack of diplomatic relations between Japan and South Korea before 1965 to demand recognition from the Japanese government. Second, there was little awareness of their difficult situation for decades both in Japan and South Korea. Third, even in the postwar era few Japanese thought that Korean hibakusha should be aided in the same way as Japanese hibakusha. The major Japanese hibakusha support associations, Hidankyō and Gensuikyō, were engaged in assisting Japanese hibakusha, and their failure to put the issue of overseas hibakusha on their agenda from the beginning delayed awareness of the abandonment of hibakusha living in South Korea. Fourth, there was no official association for A-bomb survivors in South Korea until 1967, and consequently, few of them were aware of the A-bomb relief measures in Japan. Nevertheless, the New Leftist student movement and anti-Vietnam War movement in Japan reached their peak in the late 1960s, and many of these protesters moved progressively through other issues, such as the rights and status of minority populations, with human rights issues at the forefront. In this changing social environment some Japanese became more conscious of the ongoing discrimination against zainichi Koreans by the early 1970s. They took note of other Korean-related issues such as the abandonment of A-bomb survivors in South Korea following Hiraoka Takashi’s reports and the news of Son Jin-doo’s illegal landing and consequent arrest. (Some of this information comes from Toyonaga Keisaburō, following a personal interview with the author in Hiroshima on June 28, 2015.)

Kawamura had already been treating zainichi Korean hibakusha, thousands of whom resided in Hiroshima. Those zainichi Korean A-bomb victims who succeeded in finding Japanese witnesses and had their A-bomb Certificates issued received free medical treatment, but Kawamura also treated zainichi A-bomb patients free of charge who were unable to cover the medical expenses despite their not possessing A-bomb Certificates (see Kim Sin-hwan’s memoir later in the text).

Seventy percent of the Korean A-bomb victims from Hiroshima came from Hapcheon County, and after World War II, many of the survivors returned there. Consequently, thousands of hibakusha lived in Hapcheon. Due to its relative distance from major cities, there were few doctors in the mountainous villages. Therefore, Kakkin Kaigi chose this region as the location for an A-bomb clinic.

The medical support programs implemented by the Japanese and South Korean governments between 1980 and 1986, and later, by Kawamura’s citizen-based committee were limited to hibakusha who resided in South Korea, and did not encompass A-bomb victims living in North Korea or zainichi Korean hibakusha in Japan who did not possess A-bomb Certificates.

Another important redress movement in Japan that emerged later has sought proper apology and compensation from the government for “the comfort women,” who were sexually abused by the Japanese Army before and during World War II.

In particular, Japanese Christians supporters – such as Kawamura or Reverend Oka Masaharu – viewed their nation as victimizers, and as penance for the atrocities that Japan inflicted on many Asian countries, they dedicated their lives to obtaining recognition of Korean hibakusha. Reverend Oka, who was a Protestant minister in Nagasaki, was also fighting against the violation of zainichi Koreans’ human rights in Japan, and was bent on unveiling the atrocities committed by the Japanese Imperial Army in Asia before and during the Pacific War. Following his death, the Oka Masaharu Memorial Nagasaki Peace Museum, which documented both the ravages of the atomic bomb and Japanese atrocities in the war, was established.

As mentioned earlier, this article discusses Japanese medical assistance to atomic bomb victims, who, after Japan’s defeat in World War II, had returned and settled in South Korea, following the peninsula’s division in 1948. Korean hibakusha continuing to reside in Japan as zainichi Koreans, or those select few who managed to acquire Japanese citizenship, were eligible to apply for hibakusha status. However, in practice, it remained very difficult, given that until the early 1980s, one of the two witnesses for the application had to be Japanese. Although deprived of Japanese citizenship under the U.S. occupation at Japanese insistence, some zainichi Koreans later obtained citizenship through naturalization.

Kawamura Toratarō Ikōshū, Iryō to Shinkō [Medical Treatment and Faith] (Hiroshima: Kawamura Chiwa, Kawamura Junichi, Kawamura Yuzuru, and Matsuoka Kazue, 1992), 237. Hereafter cited as Kawamura, Iryō to Shinkō.

Kim Sin-hwan, “Kankokujin Hibakusha to no Kakawari,” [Connection with the South Korean Atomic Bomb Survivors] in Hiroshima Iinkai Nyūsu [Hiroshima Committee News] No. 51, November 25, 2010: 2 in Zaikan Hibakusha Tonichi Chiryō Hiroshima Iinkai [Hiroshima Committee to Invite South Korean A-bomb Survivors to Japan for Medical Treatment], Zaikan Hibakusha Tonichi Chiryō no Michi. [The Road to Bring South Korean Hibakusha to Japan for Medical Treatment] (Hiroshima: Zaikan Hibakusha Tonichi Chiryō Hiroshima Iinkai, 2016), 542.

Mindan was the organization of Koreans in Japan (zainichi Koreans) who were ideologically connected to South Korea. Zainippon Daikanminkoku Mindan Hiroshima Chihō Honbu Kankoku Genbaku Higaisha Taisaku Tokubetsu Iinkai, [Korean Residents Union in Japan, Main Main Office of Hiroshima District, Special Committee to Take Measures for Korean Atomic Bomb Victims] Kankokujin Genbaku Higaisha 70 Nenshi Shiryōshū [Source Book of the 70-year History of Korean Atomic Bomb Victims] (Hiroshima, Zainippon Daikanminkoku Mindan Hiroshima Chihō Honbu Kankoku Genbaku Higaisha Taisaku Tokubetsu Iinkai: 2016), 20. Hereafter cited as Mindan, Kankokujin Genbaku Higaisha 70 Nenshi Shiryōshū.

Itō Sonomi, “Kenri o Kachitoru made: Nihon de Zaikan Hibakusha o Sasaeta Hitobito,” [Until We Obtain Our Rights: People Who Supported Korean Hibakusha in Japan] Buraku Kaihō Kenkyū 23 (January 2017), 109. Hereafter cited as Itō, “Kenri o Kachitoru made.”

Kawamura Yuzuru. Interview with the author. Personal interview. Hiroshima, July 10, 2016. Hereafter cited as Kawamura. Interview with the author.

For more on the South Korean health care system, see: Shin Dong-won, “Public Health and People’s Health: Contrasting the Paths of Healthcare Systems in South and North Korea, 1945-60,” in Public Health and National Reconstruction in Post-War Asia: International Influences, Local Transformations eds. Liping Bu and Ka-che Yip (London; New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2015), 108.

“‘Wish to Atone’: Hiroshima Doctor Carries on Father’s Legacy of Treating Korean Hibakusha,” June 29, 2015. (accessed: November 15, 2017).

Anthony DiFilippo, Japan’s Nuclear Disarmament Policy and the U.S. Security Umbrella (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006), 71. Ideological tensions within Gensuikyō did not end with the formation of Kakkin Kaigi. With the 1963 Limited Test Ban Treaty, “socialists opposed nuclear testing by any country, while the communists were willing to accept Soviet testing.” This further ruptured Gensuikyō, resulting in the Socialist Party leaving the group and establishing Gensuikin in 1965.

Kawamura Toratarō, “Tonichi Chiryō no Torikumi no Hajimari,” [Beginning of the Program to Treat South Korean Hibakusha in Japan] in Zaikan Hibakusha Tonichi Chiryō Hiroshima Iinkai, Zaikan Hibakusha Tonichi Chiryō no Michi (Hiroshima: Zaikan Hibakusha Tonichi Chiryō Hiroshima Iinkai, 2016), 5. Hereafter cited as Kawamura, “Tonichi Chiryō no Torikumi no Hajimari.”

Chūgoku Shimbun, “Hibakugo Hatsu no Jushinsha mo Sōru de no Chiryō Oeru,” [Patients Undergoing the First Medical Examination and Treatment since the A-bomb Attack Finish in Seoul] September 27, 1971, Box 4, HT0400600, Hiroshima University Archives (hereafter HUA).

Chūgoku Shimbun, “Hibakusha 117 Nin o Shinryō: Hōkan Ishidan Dai 2 Jin Kaeru,” [Treating 117 Hibakusha: The Second Group of Doctors Visiting South Korea Returns Home] October 11, 1971, Box 4, HT0400700, HUA.

Chūgoku Shinbun, “Hinkon ni Kurushimu Hibakusha: Muryō Shinryō ni Enjo Hitsuyō,” [Hibakusha Struggling with Poverty: It Is Necessary to Help Them Receive Free Medical Treatment] October 2, 1971, Box 4, HT0400700, HUA.

Ishida Sada, “Zaikan Hibakusha no Kenkōshindan no Hōkoku,” [Report on the Medical Examinations of Korean Hibakusha] in Hiroshima Iinkai Nyūsu [Hiroshima Committee News] No. 47, November 28, 2008: 4 in Zaikan Hibakusha Tonichi Chiryō Hiroshima Iinkai, Zaikan Hibakusha Tonichi Chiryō no Michi (Hiroshima: Zaikan Hibakusha Tonichi Chiryō Hiroshima Iinkai, 2016), 505. Hereafter cited as Ishida, “Zaikan Hibakusha no Kenkōshindan no Hōkoku.”

Chūgoku Shimbun, “Kankoku Hibakusha ni Sukui no Te: Hiroshima no Ishidan ga Shuppatsu,” [A Helping Hand to Korean Hibakusha: The Medical Team from Hiroshima Departs] December 13, 1973, Box 4, HT0400900, HUA.

Kawamura. Interview with the author.

For more information on Indo-Nepali relations including migration, see: Kishore C. Dash, Regionalism in South Asia: Negotiating Cooperation, Institutional Structures (London and New York: Routledge, 2008), 69-73.

Asahi Shimbun, “Hibaku Kankoku Josei o Chiryō ni Maneku. Okizari Okashii: Nagasaki de Sobo Ushinatta Ishi,” [Inviting a South Korean A-bomb Survivor Woman for Medical Treatment. Abandonment is Weird: A Doctor Who Lost His Grandmother in Nagasaki] July 21, 1972, Box 4, HT0400800, HUA.

Asahi Shimbun, “Kankoku kara Chiryō ni Raihiro: Hibaku Fujin, Harada Ishi ga Shōtai,” [Coming to Hiroshima from South Korea for Medical Treatment: Harada Invites a Hibakusha Woman] November 14, 1973, Box 4, HT0400900, HUA.

No South Korean hibakusha were issued A-bomb Certificates by the Japanese authorities between 1965 and 1974. There were a few cases where they were given the certificate in the early 1960s, before the signing of the South Korea-Japan Normalization Treaty, yet their number is very small. None of the hibakusha coming to Japan on Kawamura’s invitation from 1973 possessed or could be issued A-bomb Certificates, at least until Son Jin-doo’s first legal victory in 1974. Sin Yeong-soo was the first to be given the certificate in July 1974.

Chūgoku Shimbun, “Jihi de Maneki Chiryō e,” [Inviting Patients for Medical Treatment via Self-expense] January 21, 1973, Box 4, HT0400900, HUA.

Chūgoku Shimbun, “I wa Jinjutsu ni Kokkyō Nashi: Kankoku Hibakusha, 27 Nichi ni Hiroshima e,” [There Is No Border to Humanistic Medicine: A Korean Hibakusha Arrives in Hiroshima on 27th] March 24, 1973, Box 4, HT0400900, HUA.

Chūgoku Shimbun, “Hibaku Techō o Shinsei: Rainichi, Chiryōchū no Kankoku Fujin,” [Applying for the A-bomb Certificate: A Korean Woman Coming to Japan Being Under Medical Treatment] April 12, 1973, Box 4, HT0400900, HUA.

For further information on the Japanese – South Korean intergovernmental medical relief program see Ágota Duró, “A Pioneer among the South Korean Atomic Bomb Victims: Significance of the Son Jin-doo Trial,” Asian Journal of Peacebuilding 4.2 (2016): 271-292.

Nagasaki Zainichi Chōsenjin no Jinken o Mamoru Kai, [Nagasaki Association to Protect the Human Rights of Koreans in Japan] Chōsenjin Hibakusha: Nagasaki kara no Shōgen [Korean Hibakusha: Testimnies from Nagasaki] (Tokyo: Shakai Hyōronsha, 1989), 253. Hereafter cited as Jinken o Mamoru Kai, Chōsenjin Hibakusha.

If the Korea Association is correct in estimating that 23,000 hibakusha returned to the Korean Peninsula, and 2,000 settled in North Korea, that means that about 6,000 hibakusha living in South Korea had passed away by the 1980s. Nevertheless, given the lack of official surveys conducted by the Japanese and South Korean governments – namely, on the number of A-bomb victims returning to South Korea in the postwar period – it is important to note that these numbers are estimates, and the exact numbers are unknown.

Michael Weiner, “The Representation of Absence and the Absence of Representation: Korean Victims of the Atomic Bomb,” Japan’s Minorities: The Illusion of Homogeneity ed. Michael Weiner (London and New York: Routledge, 1997), 99.

Hirano Nobuto, Umi no Mukō no Hibakushatachi: Zaigai Hibakusha Mondai no Rikai no Tame ni [Hibakusha Living on the Other Side of the Sea: For the Comprehension of the Problem of the Hibakusha Residing Outside Japan] (Tokyo: Hachigatsu Shokan, 2009), 19.

Takazane Yasunori. Interview with the author. Nagasaki, February 5, 2016.

Takazane was the former chairperson of the Nagasaki Association to Protect the Human Rights of Koreans in Japan and the former director of the Oka Masaharu Memorial Nagasaki Peace Museum. According to the 151th issue of the Kankoku no Genbaku Hibakusha o Kyūensuru Shimin no Kai Kikanshi: Hayaku Engo o! (hereafter Hayaku Engo o!) [Bulletin of the Association of Citizens for the Support of South Korean Atomic Bomb Victims: Quick Support!] (page 15), he passed away on April 7, 2017.

Ichiba Junko, “8/3 Zaikan Hibakusha ga ‘Beiseifu ha Genbaku Tōka Sekinin o Mitomete Shazai Seyo’ to Chōtei Shinsei” [August 3rd: Hibakusha in South Korea Submit a Request of Mediation with the U.S. Government about Acknowledging its Complicity in the Dropping of the Atomic Bombs and Apologizing] in Hayaku Engo o! 151 (December 2017): 4.

Kawamura Toratarō, “Nyūsu Hakkan ni Yosete,” [Contributing to the News Publication] in Hiroshima Iinkai Nyūsu [Hiroshima Committee News] No. 1, May 1985: 1 in Zaikan Hibakusha Tonichi Chiryō Hiroshima Iinkai, Zaikan Hibakusha Tonichi Chiryō no Michi (Hiroshima: Zaikan Hibakusha Tonichi Chiryō Hiroshima Iinkai, 2016), 1. Hereafter cited as Kawamura, “Nyūsu Hakkan ni Yosete.”

Kim Sin-hwan, “‘Zaikan Hibakusha Tonichi Chiryō Hiroshima Iinkai’ no Kessei to ‘Tonichi Chiryō’,” [Formation of the ‘Hiroshima Committee to Invite Korean A-bomb Survivors to Japan for Medical Treatment’ and ‘Coming to Japan for Medical Treatment’] in Zaikan Hibakusha Tonichi Chiryō Hiroshima Iinkai, Zaikan Hibakusha Tonichi Chiryō no Michi (Hiroshima: Zaikan Hibakusha Tonichi Chiryō Hiroshima Iinkai, 2016), 18. Hereafter cited as Kim, “‘Zaikan Hibakusha Tonichi Chiryō Hiroshima Iinkai’ no Kessei to ‘Tonichi Chiryō.’”

However, beginning in 1999, owing to the large number of applicants, the treatment of one person was limited to two months so that more hibakusha could receive treatment.

Besides submitting a detailed A-bomb testimony, applicants needed to have two witnesses to apply for an A-bomb Certificate.

Mainichi Shimbun, “Shimin Dantai ‘Yakume Oeta:’ Iryōhi Shikyū Jitsugen de, Hiroshima de Kaiken,” [Citizens’ Group Finished Its Duty: The Supply of Medical Expenses Is Realized; Press Conference in Hiroshima] May 13, 2016. (accessed: July 15, 2016).

Concerning the list of the Kiyoshi Tanimoto Peace Prize winners, see (in Japanese): Kōeki Zaidan Hōjin Hiroshima Pisu Senta, [Hiroshima Peace Center Public Interest Incorporated Association] “Tanimoto Kiyoshi Heiwashō Jushōsha: Dantaimei Ichiran,” [Kiyoshi Tanimoto Peace Prize Winners: List of the Group Names] (accessed: January 12, 2017).

Tanimoto Kiyoshi was an atomic bomb survivor from Hiroshima and a key hibakusha activist who helped raise awareness of the atomic bombing both in Japan and in the United States. After his death, the Kiyoshi Tanimoto Peace Prize was established (in 1987) to honor those who excelled in peace-related activities. See Caroline Chung Simpson, An Absent Presence: Japanese Americans in Postwar American Culture, 1945 –1960 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2001), 119.

Michiko Tanaka, “Korean Government Gives Award to Hiroshima Group Which Supports Korean A-bomb Survivors,” April 3, 2015. (accessed: July 15, 2016).

Mizukawa Kyosuke, “Hiroshima Group Supporting Korean A-bomb Survivors to End Its Activities,” May 13, 2016. (accessed: July 15, 2016).

Expenses for medical treatment, however, were covered by the Japanese government, since the patients participating in the program possessed A-bomb Certificates.