Abstract

How has ownership of the tiny and uninhabited Senkaku/Diaoyu islands become the most intractable issue in Sino-Japanese relations? Explanations have typically focused on legal and diplomatic issues, the context of the Cold War and the San Francisco Treaty system, and the economic and strategic values of the maritime region. This paper instead argues that people’s diplomacy by both Chinese and Japanese turned the ownership issue into a “homeland dispute,” by confirming the status of these remote and uninhabited islets as “inherent territory” of their nations, thus making it nigh impossible for their governments to make compromises and concessions. From 1970 to 1972, political mobilization and street action by Chinese activists in North America, Taiwan and Hong Kong compelled the governments of both Taiwan and Mainland China to assert Chinese sovereignty over the islands openly and to maintain those claims consistently over time. Initially in Japan, some groups and individuals supported Chinese ownership. However, state-society collaboration produced a consensus for Japanese ownership of the islands. Although an unwritten shelving agreement between the PRC and Japan kept tensions under wraps from 1978 to 2010, occasional flareups, initiated or aggravated by a combination of right-wing Japanese groups and Chinese activists from Taiwan, Hong Kong and the PRC, prevented any resolution of the dispute. The shelving agreement collapsed in the aftermath of the 2010 trawler collision incident, leading to a semi-permanent state of tensions between China and Japan.

Introduction: From Offshore Island Dispute to Homeland Dispute

The dispute over the ownership of the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands is the most intractable issue in Sino-Japanese relations, and, with the exception of the Taiwan reunification issue, the outstanding territorial dispute China has with its neighbors that arouses the strongest emotions among the Chinese people. As M. Taylor Fravel points out in his comprehensive survey, the People’s Republic of China has engaged in twenty-three unique territorial disputes since 1949, including sixteen land frontier disputes, three homeland disputes, and four offshore island disputes. Except for India and Bhutan, all of China’s land frontier disputes have been settled through bilateral agreements in which China has offered substantial territorial concessions.1

Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan fall into the second category of homeland disputes, for the PRC deemed them to be part of the Chinese homeland, and projects for the completion of national reunification. Through China’s 1984 agreement with Britain and 1987 agreement with Portugal, Hong Kong and Macau have reunited with China in 1997 and 1999 respectively.2 Taiwan, however, remains from the PRC perspective a “renegade province.”

Fravel classifies the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands in the East China Sea as one of China’s offshore island disputes, along with the Spratly (Nansha) Islands and the Paracel (Xisha) Islands in the South China Sea, and the White Dragon Tail Island in the Gulf of Tonkin. The last was settled through China’s secret transfer of White Dragon Tail Island to North Vietnam in 1957.3 At this writing, neither the East China Sea nor the South China disputes show any sign of resolution or de-escalation.

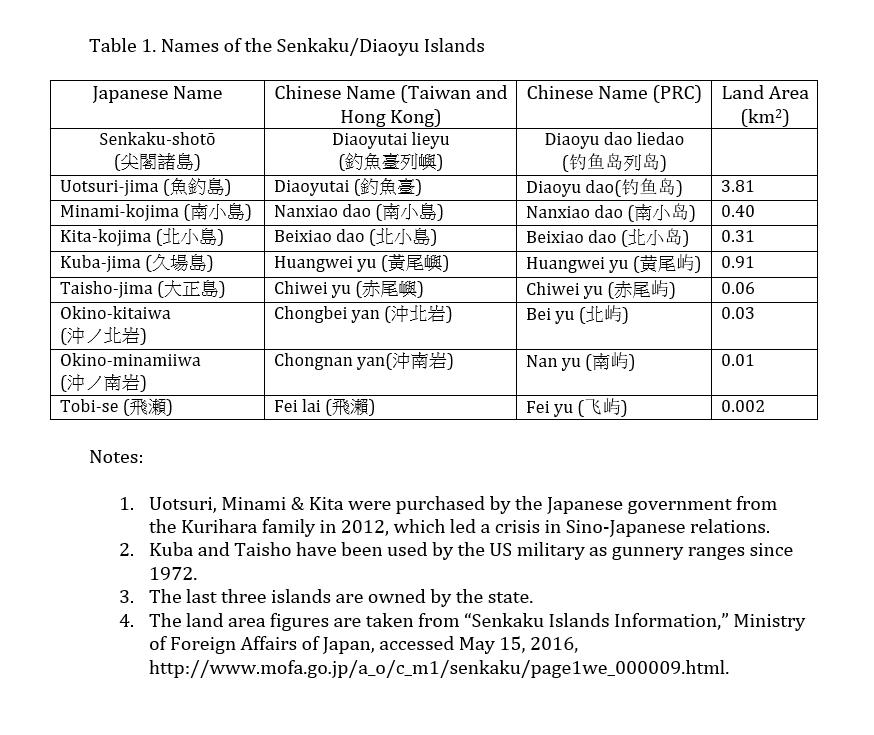

The tiny Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands would seem to be an unlikely candidate for the thorniest issue in Sino-Japanese relations. This island chain, currently under Japanese administrative control, consists of five uninhabited islets and three barren rocks, located in the East China Sea about 125 miles northeast of Taiwan and 185 miles southwest of Okinawa. Their ownership is claimed by the People’s Republic of China (PRC), Japan, and the Republic of China on Taiwan (ROC), each calling it by a different name: Diaoyu (钓鱼岛列岛) for China;4 Senkaku (尖閣諸島) for Japan; and Diaoyutai (釣魚臺列嶼) for Taiwan (and Hong Kong) (Figs. 1 and 2 and Table 1).

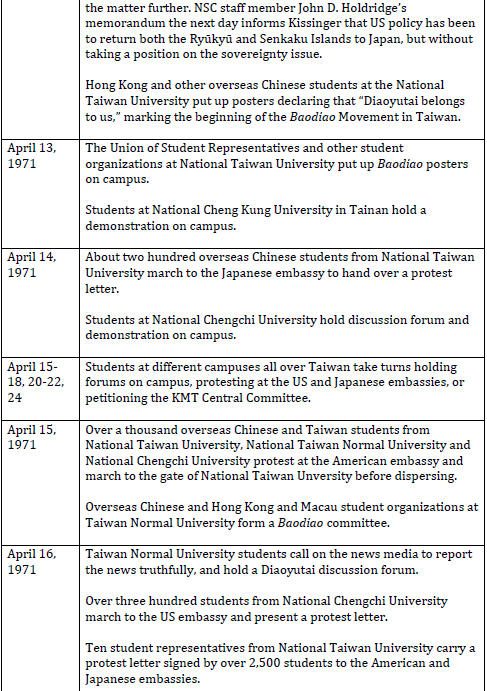

|

|

|

The Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands, with the largest island, Uotsuri-jima/Diaoyutai/Diaoyu dao, in the back. |

|

The political status of the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands before 1895 is at the heart of the dispute over their ownership: Were they terra nullius, as the Japanese contend, or were they part of the Qing Empire, as the Chinese assert? If these islands were terra nullius, then the Meiji government annexed them legitimately in 1895 under the “discovery-occupation” principle of international law. But if the islands were part of Taiwan Province in the Qing Empire, then they were taken from China by Japan under the Treaty of Shimonoseki in 1895, and should have been returned to China in 1945 in accordance with the Cairo and Potsdam declarations.5Below, we will refer to these islands as the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands to highlight the continuing conflicting claims of sovereignty. However, when we look at the controversy and associated events from the perspectives of the mainland Chinese, the Taiwanese and the Hong Kongers, or the Japanese, we will use the name Diaoyu Islands, Diaoyutai Islands, or Senkaku Islands respectively.

From 1945 to 1972, the islands were under American administration together with the Okinawan islands, over which Japan held residual sovereignty. However, discovery of potential vast oil reserves in the maritime region surrounding the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands in the late 1960s led to a dispute over whether the islands belonged to China or Japan, calling into question whether Japan’s residual rights to Okinawa applied also to the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands, and whether they should be included in the reversion of Okinawa from US control to Japanese sovereignty.

Research on the dispute has typically focused on legal and diplomatic issues, the economic and strategic values of the maritime region, or the context of the Cold War and the San Francisco Treaty system as explanations for its roots and challenges. Unryu Suganuma, Han-yi Shaw, and Ivy Lee/Fang Ming have analyzed in detail the conflicting historical and legal claims of Japan and China to substantiate their respective territorial claims.6 Koji Taira, Gavan McCormack, Yabuki Susumu/Mark Selden, and Reinhard Drifte have explored the possibilities for crisis management and resolution in light of history, geography and/or legal issues.7

As Taylor Fravel observes about China’s offshore island disputes, “Control of the islands is key to the assertion of maritime rights, the security of sea lines of communication, and regional naval power projection.”8 Mark Valencia’s many articles emphasize especially China’s and Japan’s intensifying competition for fisheries and petroleum resources over the last half century.9

Kimie Hara has situated the Senkaku/Diaoyu controversy among those territorial disputes in Asia that were a legacy of the San Francisco Peace Treaty of 1951. Japan was obligated to renounce various territories it had colonized or occupied under Article 2 of the treaty. But the precise borders of these territories and which country or government should receive each of them were left unspecified.10 This deliberate vagueness was directed against America’s Cold War adversaries, the USSR and the PRC. The consequence was several unresolved political problems in Asia, including Japan’s territorial disputes with China, Russia, and South Korea.11 Those problems constitute both a defense perimeter for Japan and a containment frontier against the Soviets and the Chinese. With specific reference to the Senkaku/Diaoyu dispute, Hara argues that, by its decision to return them along with Okinawa to Japan in 1972 but without taking a position on which country has sovereignty over the disputed islands, the US was maintaining a “wedge” between Japan and China, which also helped justify maintaining US military bases in Okinawa.12

This study emphasizes the agency of actors in the peripheries of Okinawa, Taiwan and overseas Chinese communities, often neglected or underestimated in standard accounts of the Senkaku-Diaoyu dispute that have privileged Japanese and Chinese state actors.13 We will adopt a grassroots perspective of civil society and citizen activists, in particular the Defend Diaoyutai Movement that originated in North America, Taiwan and Hong Kong in the early 1970s, spread much later to Mainland China, and flared up periodically since 1990.14

My principal findings are as follows. First, the reason why the Senkaku/Diaoyu dispute is so intractable is that it is more a “homeland dispute” than an “offshore island dispute.” The governments of China, Taiwan and Japan today each refers to the islands as its inherent or intrinsic territory (guyou lingtu 固有领土 in Chinese; koyū no ryodo固有の領土 in Japanese), making compromise exceedingly difficult, given the understanding of the contested territory as an indivisible part of the sacred homeland.15 However, this conception originated in the 1970s from people’s diplomacy or citizen diplomacy (minjian waijiao 民间外交), actions and initiatives undertaken by private citizens and non-governmental groups to impact and influence public perceptions of foreign policy issues and state conduct of diplomacy and international relations. The Defend Diaoyutai Movement or Baodiao Movement (Baowei Diaoyutai yundong保衛釣魚臺運動) erupted in the US, Taiwan and Hong Kong from late 1970 as a grassroots crusade against a perceived plot by Japan and the US to encroach on the Chinese territory of Diaoyutai. The movement derived ideological and organizational inspiration from the Civil Rights movement, the Anti-Vietnam War protests, and the American New Left. Networking and flows of news and publications across the US and national boundaries facilitated the dissemination of information and the mobilization of political protests.

Political mobilization and street action, in conjunction with historical and legal research by students and scholars, turned what started as resource competition between Taiwan and Japan into a homeland dispute. The Diaoyutai Islands were added to Chinese historical memory as part of Chinese territory taken by Japan as war booty following its victory in the 1st Sino-Japanese War. Some Japanese groups and individuals initially supported Chinese ownership, but state-society collaboration soon produced a substantial case for Japanese ownership of the islands, unifying Japanese public opinion behind the government.

The Taiwan government’s clumsy handling of diplomatic affairs and the Baodiao Movement contributed to the spread of the perception that it was “corrupt in domestic affairs and incompetent in foreign relations (duinei fubai, duiwai wuneng 對內腐敗, 對外無能).” Consequently, many overseas Chinese pinned their hopes instead on the PRC for the defense of Chinese sovereignty. From late 1971 on, Baodiao activists in the US, Hong Kong and Taiwan refocused their energies on national reunification, social service and political reform.

Benefiting from this development and other concomitant events such as the US-China opening, Beijing gained greater legitimacy in Chinese communities outside of the mainland at the expense of the ROC. During the 1978 negotiations over the Treaty of Peace and Friendship, the governments of China and Japan reached a tacit agreement to shelve indefinitely the Senkaku/Diaoyu issue (though not permanently for the Chinese).16 Beijing was eager to normalize relations and secure Japanese assistance for China’s modernization, while Japan chose not to press China on a resolution of the issue in the interest of normalization and pursuing lucrative markets in China.

Nonetheless, the social memory of Diaoyutai as sacred national territory stolen by the Japanese was indelibly etched in Chinese social memory. The dispute might be shelved, but Beijing has continued to maintain that the Diaoyu Islands were non-negotiable Chinese territory. The Baodiao movement in Chinese communities outside of Mainland China (and from the early 2000s in the PRC) would be periodically reinvigorated, either on popular initiative or in response to people’s diplomacy undertaken by Japanese ultranationalists. For more than three decades, the conflict remained manageable through the shelving agreement. However, the trawler collision incident of 2010 created a perfect storm that unraveled this tacit understanding, and created a permanent state of continuing tensions over the islands.17

The pages below will analyze the origins of the Senkaku/Diaoyu conflict in Okinawa and Taiwan, the spread of people’s diplomacy and street protests in the US, Taiwan and Hong Kong, and the aftermath of Baodiao social action. Our coverage ends with 1978 that marked a hiatus in Senkaku/Diaoyu activism until 1990, after which people’s diplomacy in spurts sustained and further spread the social memory of the islands as homeland.

Origins of the Senkaku-Diaoyu Dispute in Resource Competition

Except for Taiwanese and Okinawan fishermen active in their waters, these tiny islets would have remained unknown or forgotten, had not an international team of scientists under the auspices of the United Nations Economic Commission for Asia and the Far East (UNECAFE) conducted a survey in late 1968, and concluded in its 1969 report: “A high probability exists that the continental shelf between Taiwan and Japan may be one of the most prolific oil reservoirs in the world.”18

Even before the UNECAFE survey, Japanese industrialists, bureaucrats and academics had been alerted to the potential rich oil reserves in the East China Sea.19 The Japanese government, Tokai University and oil companies collaborated in financing three survey missions between 1968 and 1970.20 News of a potential oil bonanza produced a frenzy of applications to the Government of the Ryūkyū Islands (GRI), by private individuals in Okinawa, mainland Japanese oil companies, and American oil companies for drilling rights, nearly 4,000 by May 1969 and almost 25,000 by September 1970.21

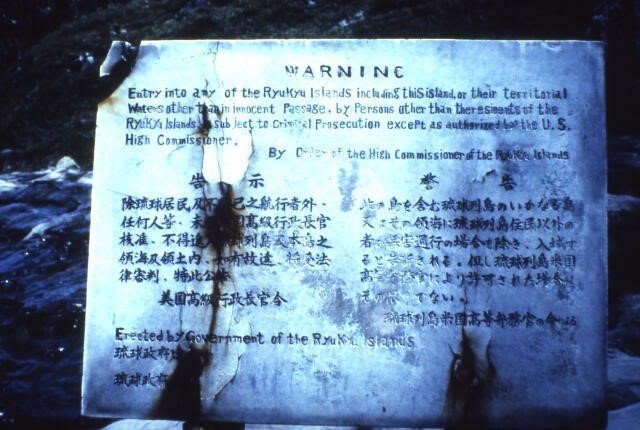

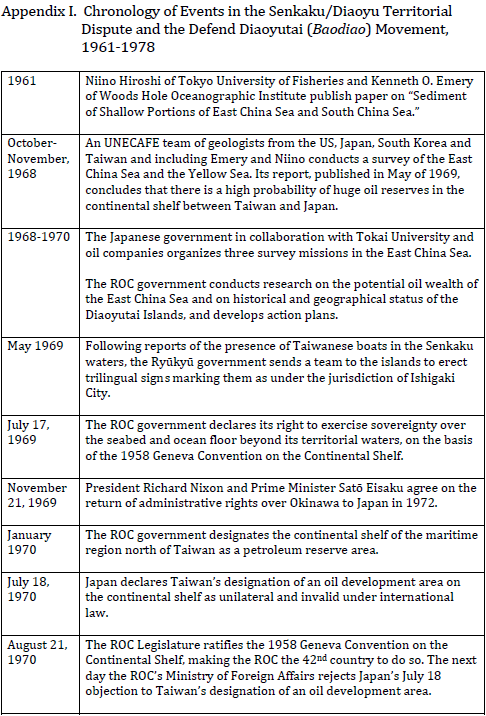

The GRI, the self-government of indigenous Okinawans created in 1952 by the United States Civil Administration of the Ryukyu Islands (USCAR), had been concerned about the increasing numbers of Taiwanese fishing vessels in Senkaku waters since the late 1950s.22 Prospects of impoverished Okinawa turning into an Eastern Persian Gulf now made securing control over the Senkaku Islands more imperative. The GRI began to conduct occasional military overflights and periodic maritime police patrols. In May 1969 it sent a team to erect warning signs in Japanese, Chinese and English on all the islands, marking them as off limits to persons other than Ryūkyū residents (Fig. 3).23

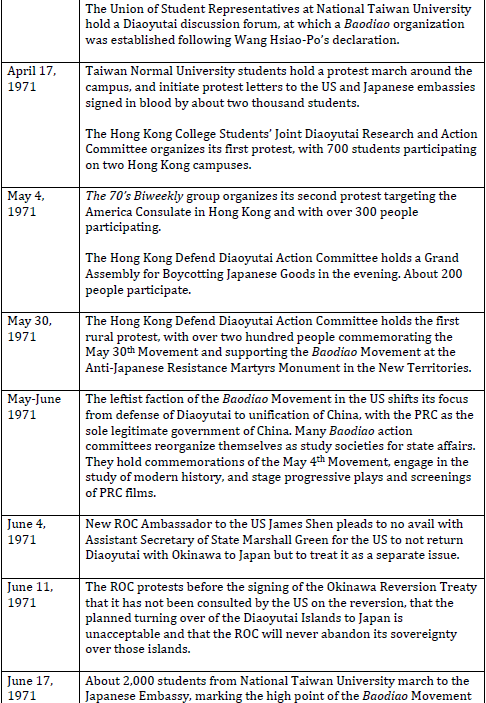

|

Trilingual warning sign erected at each of the Senkaku Islands in May of 1969 by the Government of the Ryūkyū Islands: “Entry into any of the Ryūkyū Islands including this island, or their territorial waters other than innocent passage, by persons other than the residents of the Ryūkyū Islands, is subject to criminal prosecution except as authorized by the U.S. High Commissioner.” |

On November 21 of 1969, President Richard Nixon and Prime Minister Satō Eisaku agreed on the return of administrative rights over Okinawa to Japan in 1972.24 The Prime Minister’s Office announced in February 1971 that Japan would cooperate with the US military to strengthen patrolling of Senkaku waters and expel Taiwan fishing boats. Japan also included the Senkaku Islands as a defense key point in its 4th defense plan. It further declared that, once Okinawa reverted to Japanese sovereignty, it would follow the Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) limits of the US military, within which fall the islands.25

Awareness of potential oil riches in the East China Sea prompted the Republic of China, then under the rule of the Kuomintang (KMT) or Nationalist Party, to spring into action.26 In February 1968, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs compiled a study of the Diaoyutai oil issue, proposing a systematic course of action: (1) Collection of sources connecting the islands to China, conducting proper research, and announcement of Chinese sovereignty over them at the appropriate time; (2) Immediate ratification of the 1958 Geneva Convention on the Continental Shelf (which the ROC had already signed) to strengthen Chinese claims on the basis of Diaoyutai’s location on Taiwan’s continental shelf; and (3) Conduct negotiations with foreign oil companies as soon as possible to achieve a fait accompli. This plan constituted the basis of the ROC’s strategy on the Diaoyutai Islands.27

Throughout 1968, various government agencies conducted or sponsored related research and took concrete action to strengthen Taiwan’s claims to the potential economic resources in the Diaoyutai region.28 On July 17, 1969, Taipei declared on the basis of the Geneva Convention on the Continental Shelf of 1958, that it had the right to develop its coastal continental resources, thereby implicitly claiming sovereignty over the Diaoyutai islands.29 In January of 1970, the ROC government designated the continental shelf of the maritime region north of Taiwan a petroleum reserve area, and delegated the Chinese Petroleum Corporation the task of exploring and developing the region.30

In July 1970, Japan objected that Taiwan’s declaration of an oil development area on the continental shelf was unilateral and invalid under international law. Taiwan countered by notifying Japan on August 22 that it had the right to prospect and exploit undersea resources in the continental shelf north of Taiwan in accordance with international law and the Geneva Convention on the Continental Shelf. Just one day earlier, the ROC legislature had finally ratified the convention. On September 3, 1970, the ROC promulgated a set of regulations on maritime oil exploration, and granted a consortium of seven Western oil companies the right of cooperative exploration and development in a maritime region including the vicinity of the Diaoyutai Islands. The granting of these concessions conflicted with competing Japanese and Okinawan claims.31

Back on August 31, the Okinawa Legislature issued a declaration, calling on the US and Japan to intervene forcefully to stop Taiwan from encroaching on Japanese sovereignty over the Senkaku Islands through its oil development plans and negotiations with Western oil companies. This Okinawa government statement was the first official document to lay out the basics of the case for Japanese ownership: until 1895, the islands were terra nullius, and none of the earlier documents of the Ryūkyū Kingdom and China that mentioned the islands constituted proof that they belonged to either; after ascertaining their status as terra nullius, the Meiji Government legally incorporated them as part of Okinawa Prefecture in 1895.32 This document would be echoed by a series of official statements from the Okinawa Civil Government in the early 1970s. A full official statement reiterating the same position from the Government of Japan itself, however, would not come until just over two months before the Okinawa reversion, with the publication of The Basic View of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs on the Senkaku Islands on March 8, 1972. This document further declared that the islands were neither part of Taiwan nor part of the Pescadores, and hence not part of Chinese territory ceded to Japan under the Treaty of Shimonoseki in 1895, nor subject to treaties signed after World War II obligating Japan to return territories seized from other countries.33

While the discovery of potential petroleum and natural gas reserves might have attracted widespread attention to the ownership issue, a much more immediate economic concern was that of the Taiwanese fishermen from Yilan County, the ROC jurisdiction closest to the disputed islands. Before the 1970s, Taiwanese fishermen fished in the region undisturbed, but in the summer of 1970, Okinawan patrol boats expelled them, putting their livelihood at risk.34 The plight of the fishermen was widely reported by the Taiwan press, and caught the attention of the public.35

From Resource Competition to Territorial Dispute

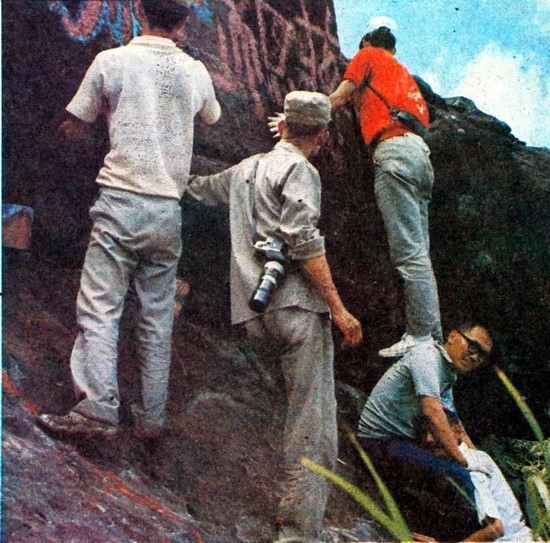

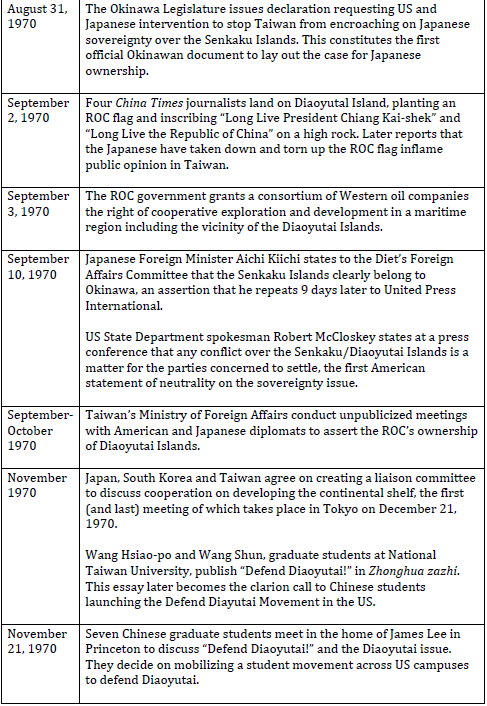

On September 1, 1970, four journalists from China Times set sail on a ROC Marine Research Laboratory vessel from Keelung for Diaoyutai. They landed on Diaoyutai Island the following day. The journalists planted an ROC flag, and inscribed in red ink “Long Live President Chiang [Kai-shek] and “Long Live the Republic of China” on a high rock (Fig. 4). On September 4, they published an account of their adventures. Further Diaoyutai news reports in the Taiwan press in late 1970, plus a rumor that the Okinawans had torn up the ROC flag planted on Diaoyutai Island and thereby offended the ROC’s national dignity, led to growing pressure from the Taiwan public on the government to take strong action.36

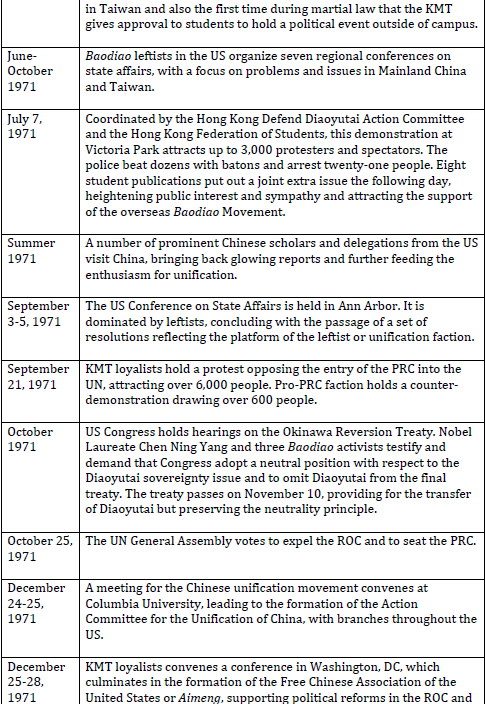

|

Four China Times journalists carving the words “Long Live President Chiang Kai-shek,” on a rock on Diaoyutai Island, September 2, 1970. |

In the initial stages of the looming dispute over ownership of the islands, the Republic of China focused on resource competition without making an open claim of sovereignty, to avoid open breaches with Japan or the US at a time when Taiwan’s position at the UN was deteriorating. On September 4, Foreign Minister Wei Tao-ming (Wei Daoming 魏道明) stated in a secret conference at the Legislative Yuan that Diaoyutai belonged to China, but this was unpublicized.37 By mid-September, Chiang Kai-shek had decided on the following Diaoyutai policy: First, settle our ownership of the continental shelf rights; Second, refrain from openly claiming ownership of the islands, but also refuse to acknowledge Japanese ownership; Third, declare to the US that we disagree with its unilateral decision to return the Ryūkyūs to Japan without consulting us, and that we reserve the right to speak on this issue.38

At a September 10 press briefing, State Department spokesman Robert McCloskey was asked what the US position was if conflict arose over sovereignty of the Senkaku Islands. McCloskey responded that it would be a matter for the parties concerned to settle.39 This was the earliest public statement of the US position on the sovereignty issue.

If the US thought that, by avoiding taking sides on a problematic issue, it could sidestep damaging relations with one of its Cold War allies, Japan and Taiwan,40 and perhaps also provoke the PRC at the very moment when the US was exploring the possibility of a US-China détente directed against the USSR, it was mistaken. Neither Japan nor the ROC was pleased by McCloskey’s response.41

The KMT government finally asserted Chinese ownership of the islands to Japan and the US through unpublicized diplomatic channels, though not openly. On September 16, 1970, Chow Shu-kai (Zhou Shukai 周書楷), ROC Ambassador to the US, verbally informed Marshall Green, Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs, about Taiwan’s legal rights to Diaoyutai.42 On October 23, James Shen (Shen Jianhong 沈劍虹), ROC vice minister of foreign affairs, stated to the Japanese ambassador in Taipei that the Diaoyutai Islands belonged to the ROC and were definitely not Japanese territory.43 On the following day, the Japanese Embassy countered with a statement that the Senkakus were incontrovertibly part of Nansei-shotō and hence Japanese territory.44

Nonetheless, at this stage the possibility still existed of a compromise over resource competition in the East China Sea. In November of 1970, an agreement was reached on the creation of a Japan-Korea-ROC Liaison Committee to discuss cooperation on developing the continental shelf.45 The first meeting of the Liaison Committee took place on December 21, 1970 in Tokyo, involving non-governmental organizations of Japan, South Korea and Taiwan. Trilateral cooperation to develop maritime resources was discussed, but not the question of territorial sovereignty and oil development rights.46 Nonetheless, the trilateral commission fanned the suspicions of Taiwan Chinese that the ROC was willing to give up territorial claims to Diaoyutai in order to secure a share of maritime resources in the East China Sea. It also aroused the immediate objections of the PRC.47 A December 3 Beijing radio broadcast responding to the liaison committee announcement marked the first assertion of Chinese sovereignty over the Diaoyu Islands. On the following day, a Xinhua News editorial on “A Conspiracy by the American and the Japanese Reactionaries to Rob China and Korea of Their Seabed Resources” blasted the Liaison Committee as an act of aggression and a US-Japan conspiracy with the connivance of South Korea and Taiwan.48 The Taiwan public’s suspicions and the PRC’s strong objection ended the prospects of joint development, and left the ROC with little choice other than to defend territorial claims to Diaoyutai.

Japan: Dissenting Voices against the Government’s Senkaku Policy

At the outset of the controversy, the Japanese government publicly declared its position that it has maintained to the present day: the Senkaku Islands constitute an intrinsic territory of Japan, Japan’s ownership is indisputable, and therefore there is no dispute.49 However, the Japanese public was far from supporting the government’s position unanimously. There were dissenting voices emanating from the press, Japanese student groups and organizations, progressive and pro-China organizations, and individual intellectuals.

A number of news commentators voiced their opposition to what they saw as a resurgence of Japanese militarism in alliance with monopoly capitalism, and warned that if the Japanese government placed troops in Okinawa and the Senkakus, and extended the ADIZ to the East coast of China, this might lead to a second Marco Polo Bridge Incident plunging Japan into another war with China.50 Students of the School of Science of the University of Tokyo and the Japan-China Friendship Society of Hosei University published issues on the Senkaku problem that opposed the Japanese government’s territorial incorporation of the islands as a plot of the militarist clique.51 The Association for the Promotion of International Trade, Japan or JAPIT (Nihon bōeki sokushin kyōkai日本国際貿易促進協会), a pro-China trade group founded in 1954, adopted a policy to “oppose the plot to purloin the Senkaku Islands” on March 7, 1972.52

On March 23, 1972, four leftist intellectuals initiated a statement entitled “Declaration of Righteous People in the Cultural Sphere of Japan to Stop Japanese Imperialism from Encroaching on the Senkakus” that was signed by ninety-five prominent intellectuals: “The Senkaku Islands were seized by Japan in the Sino-Japanese War, and historically, they are obviously territory inherently belonging to China. We cannot approve the Japanese imperialist aggression and affirm the history of aggression.” The statement warned against the Japanese people being manipulated over “territorial issues” and again becoming cannon fodder for Japanese militarist aggressors. It cautioned the Okinawans of all political persuasions not to be intoxicated by the alluring prospect of petroleum discoveries that could lift Okinawa out of poverty, and not to overlook the militarists’ hidden evil intentions. The statement called on everyone to rise and stop the aggression of Japanese imperialism over the Senkakus, which, if unstopped, will lead to its aggression against all of Asia.53

Ishida Ikuo (石田郁夫), an activist writer who was one of the four initiators of the declaration, was also a leader of the “Association for Blocking Japanese Imperialist Seizure of the Senkaku Islands” (Nittei no Senkaku Rettō ryakudatsu boshi no kai 日帝尖閣列島略奪の阻止の会). Another prominent member of this association was the eminent historian Inoue Kiyoshi (井上淸) of Kyoto University. Inoue was probably the most historically grounded domestic opponent to the Japanese government’s Senkaku claims, and his scholarship would be widely drawn on by Chinese proponents of China’s rights over the disputed islands. In 1972, Inoue published two lengthy articles in academic journals on the history and sovereignty issue of the Senkakus, arguing that the islands belonged to China and that Japanese militarists took advantage of imminent victory in the 1st Sino-Japanese War to encroach on them.54

Japan: State-Society Collaboration in Building a General Consensus on the Senkakus

These voices of domestic dissent, however, were no match for a concerted joint effort of the Japanese government, non-governmental organizations, the media and scholars to comprehensively document a case for Japanese ownership of the Senkakus. The Japanese government and academic circles organized many study societies on the Senkaku dispute since its outbreak, some with as many as sixty professors. These groups compiled evidence supporting the Japanese case for Senkaku ownership, and published research refuting the Chinese position.55 Both the government and big business, including Mitsubishi, Mitsui and major oil companies, financially subsidized this academic research. In half a year’s time, at least thirty or more publications, some over 400 pages long, were published.56 NHK broadcasted a special program on the Senkaku issue in 1972, featuring a discussion forum in which foreign ministry officials and international law professors participated, as well as interviews of oil industry executives, political commentators and law professors.57

The most indefatigable scholar on the Senkaku issue was Okuhara Toshio (奧原敏雄), an assistant professor of law at Kokushikan University in Tokyo and the intellectual foil to Inoue Kiyoshi. His prolific publications countered the evidence presented in academic studies supporting the Chinese position, and “provided the essence of most of the subsequent scholarly work supporting the Japanese claim.”58 Another productive writer on the Senkaku question was Midorima Sakae (綠間栄), Okinawan scholar of international law. His many articles from the late 1970s became the basis for a book for the general reader, entitled simply Senkaku rettō.59

By the 2nd half of 1972, the Japanese media had swung decisively in favor of the Japanese government’s position. Earlier, some of the commentary in mainstream newspapers such as Mainichi shimbun and Asahi shimbun had been critical. But now the media rallied behind the government and there was virtually unanimous support for the view that the Senkaku Islands were the inherent territory of Japan.60

Political organizations and academics followed suit. The Liberal Democratic Party was the first to make public its position affirming Japanese ownership of the Senkakus on March 28, 1972. Even leftist and progressive parties, which normally opposed militarism and advocated Sino-Japanese friendship, fell in line. The Japan Communist Party issued a commentary on March 31, voicing agreement with the Okinawa Legislature’s March 3 resolution which stated that “Clearly the Senkakus are Japanese Territory.” The Japan Socialist Party came around as well on April 13, followed shortly by the Democratic Socialist Party and the Clean Government Party.61 Academic circles and the general public too were won over or silenced by this avalanche of meticulous academic research, media commentary and party platforms.62

Street action and political activism did not play a major role in Japan over the Senkaku/Diaoyutai controversy at this time (unlike the situation in the US, Taiwan and Hong Kong, as detailed below). However, public demonstrations by neonationalist student action committees in April 1972 foreshadowed the future importance of political theater of the right-wing nationalists in Japan. These action committees were bused in small groups to protest at the PRC trade office, The Association for the Promotion of International Trade, Japan, and major bus and train stations in Tokyo, where they shouted “The Senkaku Islands are the intrinsic territory of Japan,” “Stop China from illegal seizure of Japan’s inherent territory—the Senkaku islands,” and other slogans.63

Taiwan: Government and Academic Research on Chinese Ownership of the Diaoyutai Islands

ROC government-sponsored research on the Diaoyutai issue culminated in a December 1, 1971 report by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Research and Analysis of the Sovereignty Question over the Diaoyutai Islands,” which summed up the case for Chinese ownership, and provided historical evidence and an explanation of why the ROC had not raised the Diaoyutai sovereignty issue right after World War II.64

Taiwan academics had also gotten busy researching the issue. In comparison to Japan, Chinese academic research on the disputed islands was nowhere as extensive and well financed by the government.65 Hongdah Chiu (Qiu Hongda丘宏達), a law professor at National Chengchi University, did the most thorough and influential research on the subject by a Taiwan scholar at the time from the perspective of international law.66

Chinese student activists in the US also produced research, pamphlets, periodicals and polemical literature on the Diaoyutai problem, and above all, organized street protests. Their political activism would prove more consequential than academic publications by Taiwan scholars.

Origins and Spread of the Defend Diaoyutai (Baodiao) Movement of 1970-1972

A fiery essay entitled “Defend Diaoyutai!” (保衛釣魚台!), published in the November 1970 issue of Zhonghua zazhi (中華雜誌) in Taiwan, was the clarion call that stirred Chinese students in the US to action and launched the Defend Diaoyutai Movement (hereafter the Baodiao Movement).

“Defend Diaoyutai!” was co-authored by two National Taiwan University graduate students, Wang Hsiao-Po (Wang Xiaobo王曉波), who would later play a key role in the Defend Diaoyutai Movement in Taiwan, and Wang Shun (王順). This essay opened with the quotation of a stirring May 4th Movement proclamation, “Chinese territory may be conquered, but must not be surrendered! Chinese people may be slain, but will not bow their heads! (中國的土地可以征服而不可以斷送!中國的人民可以殺戮而不可以低頭!). A parallel was thus drawn between imperialist encroachments on China in the early 20th century and the Diaoyutai dispute in 1970: now that Japan had rebuilt itself from the ashes of defeat and become an economic power, it once again extended its reach to the Ryūkyūs and prepared to occupy the Chinese territory of Diaoyutai. The essay continued with a survey of the “ironclad” historical and geographical evidence for Chinese ownership. But it was its stirring rhetoric that aroused strong responses. The US was condemned for its blatant support for the revival of Japanese imperialism. The KMT government was taken to task for its weak conduct in foreign relations. The essay concluded: “The earlier generation responded to Japanese imperialism’s plot to take over Shandong with the May 4th Movement, and awoke the national spirit of the Chinese people. Japanese imperialism was compelled to reveal its hideous face. Should our generation of Chinese youth fifty years later just watch helplessly while our territory was encroached on through the declarations and secret agreements of the great powers? … ‘No! No! No!’ We must demonstrate through our strength and actions that this generation of youth has the same capacity and determination to defend national territory!”67

The Baodiao Movement originated with the wide circulation of “Defend Diaoyutai!”, among Chinese students in the US in late 1970. Robust Chinese student organizations on a number of American campuses and vibrant intellectual networks across America with trans-Pacific linkages played key roles in the transmission of information on the Diaoyutai issue and the mobilization and coordination of political action. One important network was Dafeng she (大風社), a cultural society with local chapters established across the US in 1968 and 1969 by students from Taiwan. These chapters held reading and discussion meetings, and connected through a newsletter, which graduated to a quarterly (Dafeng jikan 大風季刊) in 1970.68 Another important network was the Kexue yuekan (科學月刊), a scientific monthly for Taiwan readers edited and published by a network of Taiwan graduate students in the US.69 Chinese-language periodicals published in Hong Kong also played an important cultural role. Given that the Hong Kong cultural scene was ideologically diverse and relatively free from political interference, as compared to Taiwan or the Mainland, some of its magazines served as an important medium for conducting trans-Pacific conversations on global events and intellectual currents, questions of diasporic national identity for the overseas Chinese, the role of Chinese intellectuals, and the future of China, Taiwan and Hong Kong.70

At a Dafeng she meeting in Princeton on November 21, 1970, seven Chinese graduate students met to discuss “Defend Diaoyutai!” and the Diaoyutai issue. All agreed that they had a citizen’s duty to contribute to the defense of China’s territorial sovereignty, and decided to mobilize a student movement to defend Diaoyutai on the model of the US anti-war movement.71 They notified friends on various college campuses through the Dafeng she network, and distributed a bilingual pamphlet, “What You Should Know about Diaoyutai” (釣魚台須知). The group’s request for the support of a Baodiao Movement by Chinese language publications in the US was enthusiastically received at the December 13 meeting of The Society for the Advancement of Chinese Publications (華人刊物協進會) in New York.72

In response to this initiative, a series of discussion forums were held and Baodiao action committees established on many US campuses, including the University of Chicago, New York University, Columbia University, University of Wisconsin-Madison, University of California at Berkeley, and Stanford University.73 A group of over thirty students from the East Coast founded the New York Branch of the Action Committee to Defend Chinese Territory Diaoyutai (保衛中國釣魚臺行動委員會紐約分會) on December 22, 1970. They issued a Declaration to Defend the Chinese Territory Diaoyutai (保衛中國領土釣魚臺宣言), advocating:

- Resolutely oppose the revival of Japanese militarism.

- Defend China’s sovereignty over the Diaoyutai Islands with full strength.

- Oppose the American conspiracy favoring the Satō administration.

- Reject any international plan for joint development before sovereignty has been settled.74

The principles enunciated in this declaration were adopted by the Baodiao action committees that sprang up on many US campuses by early 1971.75 The Kexue yuekan network served as a continent-wide forum for the transmission of news, circulation of political discussions, and building trust among Baodiao activists.76 On January 4, 1971, 500 copies of its news bulletin focusing on the Diaoyutai dispute were sent out to the Kexue yuekan mailing list. Later that month, Kexue yuekan’s news bulletin was transformed into a weekly bulletin on Diaoyutai (釣魚台快訊).77 Baodiao activists and action committees at various US campuses produced a substantial amount of publicity materials, informational pamphlets, and periodicals that aimed to mobilize public support for the movement.78

Circulation of information via publications and discussion forums was followed shortly by political action in the form of demonstrations across the US, first on January 29 and 30 and then on April 9 and 10, 1971. How did the Baodiao movement succeed to quickly attract the political participation of significant numbers of Taiwan and Hong Kong students in the US, given that many were apolitical, seeking to settle down in the US and earn the 3 Ps— PhD, Permanent Residence, and Property?79 Moreover, Taiwan students, who were educated in a politically repressive environment that stressed loyalty to the KMT and penalized unauthorized political actions, had even more reason to be cautious than their Hong Kong counterparts. In contrast, Hong Kong students did not have to fear reprisals by the KMT government, had much easier access to leftist publications, and were generally more open to identification with the PRC.80

The major reason why the Baodiao Movement gained broad support among Chinese students in the US was the widely shared public anger at Japan for its perceived scheme to rob China of its rightful territory to satiate Japanese greed for oil. The collective grievance of the Chinese was triggered by their historical memory of past Japanese aggression coupled with current news of Japan’s bullying of the ROC, as evidenced by Okinawa patrol boats expelling Taiwanese fishermen from the vicinity of the Diaoyutai Islands, and the Okinawan authorities reportedly tearing up the ROC flag planted by the China Times journalists. This shared outrage, even more than resource nationalism, was the fundamental reason for the rapid spread and passionate character of the Baodiao Movement.81

Stirring rhetoric and powerful images in the Baodiao literature galvanized the hitherto largely apathetic Chinese students. A major trope is the Baodiao Movement as the New May 4th Movement (新五四運動). This was anticipated by the two Wang’s incorporation of a May 4th Movement slogan in the beginning section of their essay “Defend Diaoyutai!” Berkeley graduate student Guo Songfen’s (郭松棻) fiery speech at the San Francisco rally on January 29, 1971, explicitly proclaimed the date as “the beginning of the Second May 4th Movement in China.” Guo declared: “If this [Taiwan] government cannot act in accordance with the welfare of the people, we must unite on the basis of the patriotic spirit of May 4th to criticize it. If after our criticism and censure, this government is still dithering around and going through the motions, and cannot stand up … then we should overthrow this government …”82

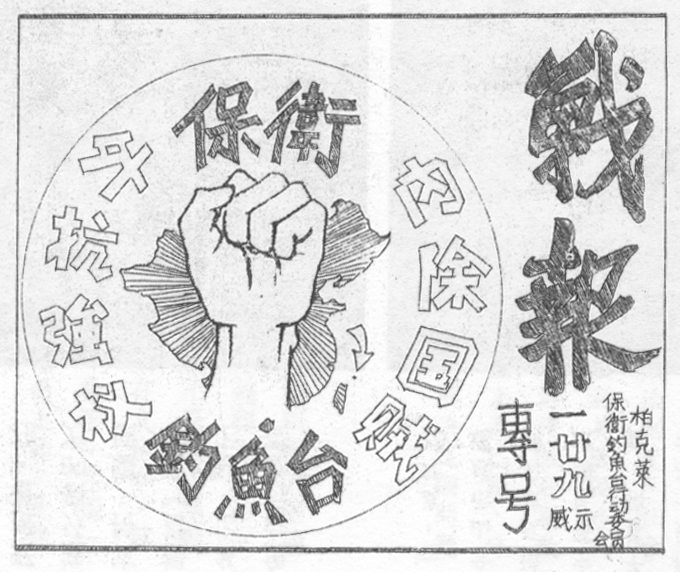

The special first issue of the Berkeley Baodiao Action Committee’s militant newsletter Zhanbao 戰報has on its cover the image of a raised clenched left fist framed at the top and the bottom by the slogan “Defend Diaoyutai 保衛釣魚台” and at the right and the left by the May 4th Movement slogan “”Eradicate traitors internally and resist foreign subjugation externally內除國賊,外抗強權.” In the background is a map of China and Taiwan, with an arrow pointing to the approximate location of the Diaoyutai Islands (Fig. 5).83 The explicit linkages of their protests to the slogans and the targets of the May 4th Movement valorize the students’ political legitimacy as the latest in a series of patriotic 20th century Chinese student movements, and draw present-day parallels to Japanese aggression and national government weakness in the May 4th era.84

|

Cover of Zhanbao’s special issue on the January 29, 1971 Baodiao demonstration in San Francisco. |

A second and related trope in Baodiao literature is the evocation of the memory of the Anti-Japanese War of Resistance, an effective appeal to the shared sense of injustice aroused by Japanese militarists again trying to rob the Chinese people of their sacred territory. The cover art and its accompanying poem for the University of Wisconsin’s special issue on the Baodiao Movement make a strong visual and rhetorical statement (Fig. 6). A salivating wolf in a Japanese military uniform has one claw on Okinawa and another extending towards the Diaoyutai Islands, while a young Chinese patriot gets ready to slay it with a spear. The poem reads:

Eight years of the War of Resistance are still fresh in our memory,

Our hot blood boiling, we swear to protect sovereign rights and fight for national dignity;

The bones of tens of thousands of martyrs are still warm, our loyal hearts are still here,

How can we allow the Japanese bandits to commit aggression again?

|

Cover of University of Wisconsin’s special issue on the Baodiao Movement. |

As the movement progressed from the exchange of information and ideas to the planning of protests and demonstrations, American political and social movements provided valuable models. A number of Chinese students who became Baodiao activists had participated in the social movements in the US during the 1960s. They were therefore familiar with the logistics and political requirements of holding marches, including securing the necessary official permits, planning routes, disseminating publicity, and maintaining order. These skills facilitated the mobilization of the Baodiao Movement.85 Chinese with immigrant or American born background who had been involved in community work also acted as liaisons mobilizing support and participation from Chinatowns and the wider Chinese community.86

The First Series of Baodiao Protests in Late January 1971

As the Baodiao Movement took shape in late 1970 and early 1971, a collective decision was made by the Baodiao action committees to hold demonstrations across the United States on January 30 when the winter break would be ending.87 Efforts were made to bridge differences between factions and forge a united front for the cause of nationalist defense of Chinese sovereignty. Organizers agreed that the movement should be “nationalist [rather] than political” in orientation, so that it would represent the unity of the Chinese people in opposition to Japanese militarism. Accordingly, neither the ROC nor the PRC flags were to be displayed, and songs and slogans were to refer only to Chinese compatriots rather than to specific Chinese regimes.88

The Berkeley Baodiao Action Committee, however, opted to hold the San Francisco demonstration one day earlier on January 29.89 The San Francisco protest had a more diverse constituency and a more radical platform than the other demonstrations, held a day later in New York, Washington DC, Chicago, Los Angeles, Seattle, and Honolulu. The Berkeley Baodiao Action Committee’s agenda was unapologetically political rather than national. It consciously called for unity with and support from the Bay Area Chinese American community. It was allied with Wei Min She, an Asian American activist organization in San Francisco Chinatown that was founded in 1971 and included both Asian American youth as well as students from Hong Kong and Southeast Asia.90 The San Francisco rally had a higher proportion of Hong Kong students and Chinese American youth than the other rallies. In addition to overseas students from nine Bay Area campuses, also prominently present were Cantonese-speaking Chinese Americans and members of the militant Red Guards Party, an Asian American youth organization founded in in San Francisco in 1969.91

As spokesman for the committee at the demonstration, Liu Daren (劉大任), a doctoral candidate in political science at UC Berkeley, called on students and compatriots to unite and protest to the governments of the US, Japan and the ROC. Speakers condemned US monopoly capitalism and imperialism, the revival of Japanese militarism, and Taipei’s failure to uphold sovereignty rights and national dignity.92

Over five hundred demonstrators marched to the ROC Consulate under the lead banner of “Dare to Die to Oppose the Selling Out of Diaoyutai” (誓死反對出賣釣魚台). The protest letter presented to Consul General Chou T’ung-hua (Zhou Tonghua 周彤華) warned: “We protest the weak, muddled, fatuous and impotent attitude demonstrated over the Diaoyutai affair by the government you represent. We solemnly warn you: Don’t twiddle with our sacred territory. All officials handling the Diaoyutai affair must bear responsibility to all Chinese people to absolutely not permit the replay of the Nishihara loans that resulted in loss of sovereign rights and national humiliation.”93 The demonstrators then proceeded to the Japanese Consulate, and after a standoff, a consular representative agreed to accept their protest letter.94

In contrast, with the exception of the Seattle demonstration, all of the January 30 protests targeted the Japanese Consulate but not the ROC Consulate, to avoid creating the impression that the movement was directed against the Taiwan government. Most of the fifteen hundred protesters in New York were Taiwan and Hong Kong students from thirty colleges, along with some Chinese intellectuals and professionals from the East Coast .95 Like the Berkeley Baodiao Action Committee, the New York organizers also reached out to the Chinatown community. I Wor Kuen, the East Coast equivalent of the San Francisco Red Guards, participated in the march, but it had to march at the rear of the contingent and refrain from carrying the PRC flag or shouting radical slogans.96

Perhaps the most enduring cultural product of the Baodiao Movement is “The Diaoyutai Fighting Song (釣魚台戰歌),” collectively composed by the Baodiao Action Committee of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and first sung at the January 30 protest in Chicago:

Amidst rolling and turbulent waves, in the East China Sea far way,

Stands a group of beautiful islets.

Diaoyutai, bravely looking down on the Pacific.

Diaoyutai, defending our bountiful territorial seas.

The wind roars, the sea howls.

Our sacred territory, the treasured Diaoyu isles.

Symbolizing that we are heroic and unafraid of violence.

Diaoyutai, how much laughter you bring to the fishermen.

Diaoyutai, containing our priceless treasures.

Roar angrily, Diaoyutai.

We will fight for each inch of earth and resist till death.

We will show contempt for the Japanese robbers!97

|

YouTube version of song with interpolated news video clips |

The “Diaoyutai Fighting Song” was adopted as the unofficial anthem of the movement at subsequent Baodiao protests, both in 1971 and at the revival of the movement in later decades.

By demonstrating at the San Francisco ROC Consulate, the Berkeley Baodiao Action Committee explicitly criticized Taipei for political inaction and rejected the majority position that the movement should be politically nonpartisan in orientation. This radical stance was confirmed by Guo Songfen’s article for the first issue of Zhanbao, published on February 15, “The Diaoyutai Affair — Which is More Important: Its Nationalist Nature or Its Political Nature?” The KMT government was attacked for adopting a docile foreign policy that played into the hands of the Satō government’s militarist expansion policy and made concessions at the expense of the interests of the nation. Moreover, the article charged, intentionally or not, the governments of Japan and Taiwan were inciting hatred between the peoples of China and Japan, who must join forces to oppose such “vicious, irresponsible behavior.”98

The anti-imperialist struggle of the Asian peoples was linked to the Asian American fight for social justice. Zhanbao denounced KMT White Terror tactics in Taiwan and Chinese America. Also under fire were Chinatown institutions controlled by older generations with close and long-standing ties to the KMT, such as the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association and Young China Morning News (少年中國晨報), founded in 1910 by the Revolutionary Alliance (Tongmenghui同盟會), the precursor to the KMT. The ultraconservative leaders of the old Chinatown organizations were deemed too focused on supporting the KMT and unable to address the needs of the Chinese community. The Chinatown old guard’s close links with the KMT also made it an impediment to the Baodiao Movement. In the words of Zhanbao, “This movement raised the political consciousness and interest in politics of the Chinese community, letting it disengage from the propaganda of KMT’s Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association. This is a very meaningful and worthwhile endeavor.” 99

Thus, Berkeley’s action committee presented a radical internationalist perspective that sought to embrace all peoples in a united front against militarism and imperialism, as well as foreshadowing the future splintering of the Baodiao Movement into political factions. However, at this early stage of the movement, most participants remained committed to a nationalist alliance against Japanese encroachment on Diaoyutai. The KMT’s mishandling of the controversy would change all that.

Taipei’s Reactions to the Baodiao Movement

Central Daily News reported on the mobilization of overseas Chinese students on the east coast to defend Diaoyutai just one day after the formation of the New York Baodiao Action Committee on December 22, 1970. As early as January 5, 1971, Taipei received alarming reports from ROC diplomats in the US that students were planning protest marches on January 30 and initiating signature drives demanding that the ROC government defend Diaoyutai sovereignty.100

ROC Foreign Minister Wei Tao-ming recognized that Taipei was in a bind. Letting the student movement develop freely would strengthen the government’s position in negotiations with Japan and the US. But actively pursuing sovereignty claims and failing to rein in the Baodiao Movement would complicate ROC-Japan and ROC-US relations at a time when international support for its UN membership was waning. The ROC government’s avoidance of open conflicts with either Japan or the US created a strong impression that Taipei was unwilling or unable to fight for Chinese sovereignty. Wei was concerned about the negative impact on the ROC’s competition with the PRC over the hearts and minds of the overseas Chinese,101 a fear borne out by subsequent developments.

Official newspapers and publications, driven by the KMT’s anti-Communist logic, consistently conveyed the view that the Baodiao Movement was manipulated and used by the Communists.102 ROC diplomatic personnel and KMT officials also tried to suppress or disrupt the activities of the movement. These measures alienated overseas students who felt they were unfairly labeled as reds, and led many to eventually lose faith in the Taipei government and identify instead with the PRC.103

In January of 1971, under direction from the central government, ROC consular officials attended Diaoyutai discussion forums held on various campuses to reassure students of the government’s determination and to dispel their suspicions. But Taipei provided the diplomats in the US with no concrete details on how the government was managing the Diaoyutai problem. Consequently, they were unable to respond adequately to the students’ sharp questions and allay their concerns.104

Following the January 29 and 30 demonstrations, consular officials recognized that students demanded concrete action not just reassuring words, and recommended that Taipei provide hard information on its negotiations with the US and Japan. They also pointed out that postponing talks on Diaoyutai ownership while conducting talks on joint development would aggravate student concerns, and warned that if students continued to be dissatisfied with government actions, the Baodiao movement could well morph into an anti-government movement.105

The Taipei government decided to dispatch two officials to the United States to “advise and guide” (shudao疏導) the Taiwan students, reassuring them on the government’s position on Diaoyutai and preventing them from becoming subverted by Communist activists.106

Between mid-February and mid-March, Education Ministry official Yao Shun (姚舜) and KMT Central Committee official Zeng Guangshun (曾廣順) traveled throughout the US, and consulted with local consular officials, KMT chapter members, and Chinese scholars and students. Unfortunately, Yao was no better briefed on what concrete actions might have been taken by the Taipei government than the ROC diplomats in the US. He was therefore unable to answer many of the students’ pointed questions at Diaoyutai discussion forums held on over ten university campuses. As described in sarcastic student reports on his trip, Yao was the one who was being advised and guided.107

Zeng, Yao and ROC Ambassador to the US Chow Shu-kai concluded that Taipei must undertake appropriate measures to address the concerns of the students.108 Yao Shun emphasized that the government should listen to the students’ demands: (1) Send naval vessels to patrol the Diaoyutai maritime region; (2) Stop for the time being talks on the joint development of maritime resources with Japan and South Korea; and (3) Make a formal declaration about Diaoyutai being Chinese territory. Yao argued that implementing these three measures would meet the bottom line of student demands and bring an end to their protests. This militant proposal was rejected due to the strong opposition of some senior KMT elders and officials.109

On February 23, 1971, the ROC under public pressure finally asserted territorial claims publicly for the first time, moving beyond simply rejecting Japan’s claims and behind-the-scene negotiations. Foreign Minister Wei Tao-Ming declared at an open session of the Legislative Yuan: “Our disagreement is based on ground that from historical, geographical and usage viewpoints, these islets should belong to Taiwan. Our views and position on this issue have been repeatedly communicated to the Japanese government [but not made public previously]. What is involved in the case of the Tiao-Yu-Tai Islets is sovereign rights and we shall not yield even inch of land or piece of rock.”110

The Second Series of Baodiao Protests in Early April 1971

This public declaration of Taiwan’s territorial rights over Diaoyutai, however, was insufficient to assuage the Chinese public in the United States. In March of 1971, 523 eminent Chinese scholars in the United States sent an open letter to Chiang Kai-shek. The Chinese professors demanded the defense of rights over the islands and refusal to engage in joint development of oil resources before settlement of the sovereignty issue.111

Berkeley’s Baodiao Action Committee initiated an open letter to Chiang Kai-shek that was supported by 60 Baodiao action committees and sent to Taipei on March 12. It insisted on a government response to ten demands, including a declaration to the world and concerned governments by March 29 that Diaoyutai was inviolable Chinese territory, a strong and publicized protest to the government of Japan for its barbaric acts of aggression, and dispatching troops to occupy the islands and naval boats to patrol the surrounding seas to safeguard China’s sovereignty and the fishermen’s safety. The ROC government remained silent.112

The first round of demonstrations had not led to any substantive visible action on the part of the Taipei government. The students were concerned that it might abandon its claims to the islands to preserve its UN seat, and were also upset at perceived US favoritism towards Japan.113 KMT officials and consular staff alienated many Chinese students, for they seemed only interested in tamping down student protests, and failed to provide either accurate information back to Taipei or information on government policies in response to the students’ questions. The KMT press’s labeling of students as Communist conspirators or as innocent dupes being used by Communist bandits and fellow travelers had already antagonized many.114 Even worse, KMT agents on US campuses engaged in sabotage and intimidation: anonymous letters attacking students involved in the Baodiao movement, planting sugar in the fuel tanks of Baodiao activists’ cars, and mobilizing parents to write letters to dissuade students from participation.115

The local Baodiao action committees therefore agreed to hold a second series of protests on April 10, 1971. The Berkeley Baodiao Action Committee again opted to hold its demonstration in San Francisco a day early. Compared to the first series of protests, participants in this round of demonstrations had hardened their position considerably against the ROC government.

At the San Francisco protest on April 9, over five hundred participants, including students from twelve colleges and universities, Chinatown residents, and others gathered in Portsmouth Square . Student speakers condemned Japanese militarist aggression, unprincipled US support for Japan, and the KMT government’s feeble handling of the Diaoyutai sovereignty issue and its censorship and repression of patriotic students. The rally was interrupted by five or six thugs hired by Chinatown leaders. They charged the podium, grabbed the microphone, and engaged in fisticuffs with demonstrators. The thugs were neutralized by the crowd and ran away when the police arrived.116

After the incident, the demonstrators regrouped and marched to the ROC Consulate. En route more Chinese and American youth joined the march. Consul-General Chou T’unghua (Zhou Tonghua周彤華) recited some generalities in response to the demands raised by the protest letter, furthering angering the demonstrators. The protesters then proceeded to the Japanese Consulate and the Federal Building where they presented their protest letter, before concluding with rousing slogans and songs.117

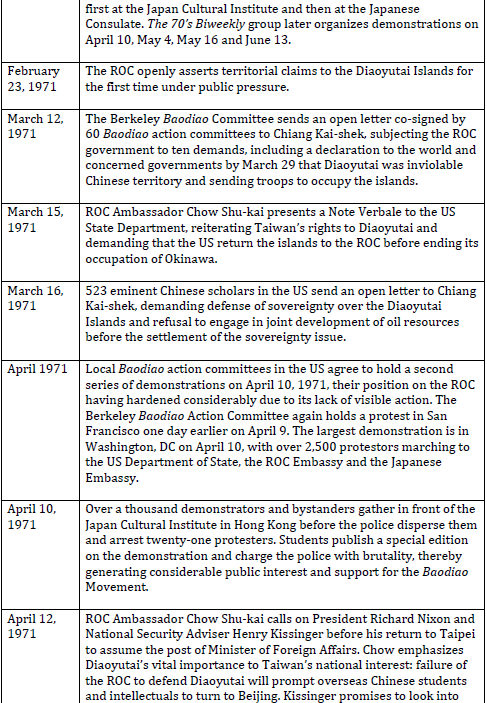

On April 10, about 2,500 protesters all over the US and Canada marched in Washington DC (Fig. 7). Li Woyan (李我焱),118 a postdoctoral fellow in physics at Columbia University, was principal coordinator and chair. Many demonstrators were taken by surprise when they saw Li and other leftist leaders donning red armbands, an insignia of the Cultural Revolution, a sign that the radicals were in control and breaking with the earlier consensus within the movement that the protests should focus on unity and not highlight ideological differences.119

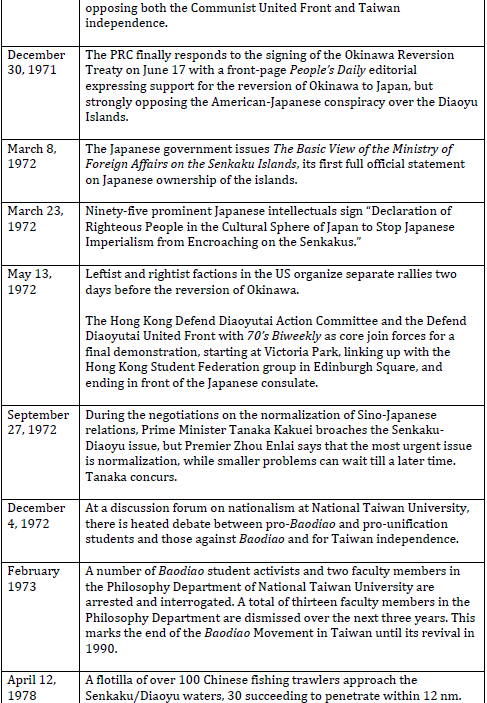

|

The Baodiao demonstration in Washington, DC on April 10, 1971. |

The demonstrators’ first stop was the US Department of State. Three representatives met with Thomas Shoesmith, head of the ROC desk, who simply repeated the American position of not taking sides on the territorial dispute. The next stop was the ROC Embassy where the three representatives met with Ambassador Chow Shu-kai and asked him about the ten demands in the open letter dated March 12. Ambassador Chow indicated that he did not know about the contents of the letter, and emphasized that he could not respond on behalf of the government, but could only express his personal opinion. He declined to respond to the crowd outside directly. The protesters were upset.120

The final stop was the Japanese Embassy. When the representatives raised the question of sovereignty over Diaoyutai, a Japanese diplomat answered to each question: “No comment!” When the representatives pressed the diplomat on why there was no comment, the response was: “Didn’t your government representatives also say ‘no comment’ to each question?” This was a sarcastic reference to the response by Foreign Ministry spokesman Wei Yusun (魏煜孫) on September 18, 1970, when he was asked about the Okinawan removal of the ROC flag planted at Diaoyutai by the China Times journalists.121

Disappointed by the results of the protest, three to four hundred demonstrators met that evening at the University of Maryland to discuss future directions. Some argued strongly for withdrawing support for the KMT government that paid no heed to student demands and was unable to defend national territory. Instead, the movement should turn to the PRC for protecting Diaoyutai sovereignty and support its entry into the UN.122

The second issue of Berkeley Baodiao Action Committee’s Zhanbao, published in June of 1971, both heightened the radical tone of the first issue and broadened the range of issues. As Jian Yiming (簡義明) has pointed out in a pioneering essay, Hong Kong magazines in the 1960s and the 1970s constituted a significant platform for political and literary discourse among Chinese intellectuals in Taiwan, Hong Kong and the US, who shared an oppositional stance toward the KMT government and an optimistic and romanticized view of the PRC and the Cultural Revolution. Guo Songfen was a participant as reader and author in this intellectual exchange, and his essays for Zhanbao were in many respects extensions of political discourse carried on in Pan Ku (Pan Gu 盤古),123 a Hong Kong magazine founded by a group of nationalistic intellectuals in 1967.124

In that year, Bao Yiming (包奕明), a Taiwan intellectual who had moved to Hong Kong via Columbia University, published under the pseudonym Bao Cuoshi (包錯石) a highly influential article in Pan Ku entitled “Study the Whole China — From Bandit Studies to National Studies研究全中國— 從匪情到國情.” Bao, who later became a leader in the Hong Kong Baodiao Movement, was initiating a dialogue with overseas Chinese students and those preparing to study abroad, arguing that they, along with warlords and compradors, had been three pillars of foreign domination of China. Corrupted by KMT propaganda and Western education demonizing Communist China, the overseas students should move from the biased perspective of “bandit studies” (匪情) to “national studies” (國情) to better understand China and Taiwan. His articles, authored singly and co-authored with various Hong Kong collaborators and published in Pan Ku and other Hong Kong magazines, created a huge storm in Chinese literary circles.125

Particularly important is Bao Cuoshi’s article on “Overseas Chinese’s Divisions, Homecoming and Opposition to Independence海外中國人的分裂, 回歸與反獨” (1967), co-signed by over ten Hong Kong intellectuals as representing their consensus. Bao et al. were addressing the alienation of the overseas Chinese under conditions of political division and spiritual exile. While the Chiang regime was dividing China politically, Taiwan independence would divide China ethnically, pitting Taiwanese against Mainlanders. The overseas Chinese must “come home” to the People’s Republic of China, since, despite authoritarian rule and collective regimentation, the Communist government was the first one in China’s history to fully mobilize the Chinese people, unleash their full potential, and make full use of China’s land resources.126

These Pan Ku articles initiated the idea of “national studies” and the homecoming discourse, which were expanded on and given a concrete map for implementation by Guo Songfen and the Berkeley Baodiao Action Committee.127 Two of Guo’s articles for the second issue of Zhanbao reflected similar consciousness, analytical methods, and philosophy of practice as those of Bao et al.’s essays. “Overthrow the Clique of Doctoral Compradors! 打倒博士買辦集團!” pointed out the “comprador” nature of the KMT government, both on the mainland and on Taiwan, which professed loyalty to the US government and acted as apologist for American imperialism in East Asia. Those “slaves of foreigners” who studied in American institutions of higher learning were the most important national puppets bowing to the American empire, identifying with American interests, and serving invasive American culture. They were dedicated to the direct or indirect support of American colonization, and absolutely opposed to challenging the colonial conditions of the American military presence. American social science pretended to be objective, but in reality supported the American status quo. Overseas students blindly applying this social science to Taiwan were reinforcing American colonization of Taiwan’s culture and thought.128

“Taiwan Independence Extremism and Big Nation Chauvinism台獨極端主義與大國沙文主義” criticized the Taiwan Independence Movement. But Guo also admitted that the unification movement might bring big nation chauvinism, as independence advocates feared. Guo stated that his identification with the PRC was not based on the illusions of the “Big Nation,” but on the ideals of socialism. He expressed sympathy for those independence advocates whose families had suffered grievously during the February 28 Incident of 1947, when over 10,000 members of the Taiwanese elite were killed. But he argued that Taiwan independence was illusory, for in the end the political and cultural control of Taiwan by the American and Japanese imperialists would be inevitable. Guo’s view was more substantial and empathetic than Hong Kong’s homecoming discourse, which criticized Taiwan independence mercilessly and took an optimistic view of unification.129

To know China through “national studies” and the acceptance of “homecoming” to the PRC would become the direction of the Baodiao Movement following the disappointing April 10 protests.

The KMT’s Last Stand to Dissuade the US from Turning Over the Islands to Japan

Was the charge of KMT incompetence and lack of action by the radical Baodiao activists justified? Undoubtedly Taipei’s paranoia about the student movement, its repressive measures and its lack of transparency in policy making and diplomatic negotiations seriously undermined its legitimacy. Its conduct of foreign relations was hampered by the growing weakness of its international position and fear of losing Japanese and American support for its membership in the UN. Prioritization of keeping Taiwan’s UN seat over defense of Diaoyutai rights kept the ROC government from pressing too hard and too openly on the Diaoyutai issue with Japan and the US. In any event, Japan consistently refused to conduct substantive conversations with Taiwan on the sovereignty issue despite an American initiative asking Japan to do so.130

The ROC could also have moved with greater urgency and timeliness in its dealings with the US on the issue. Nonetheless, the ROC never compromised on its sovereignty claims to Diaoyutai, and it would be difficult to disagree with Chiang Kai-shek’s assessment in his April 7, 1971 diary entry that a military solution of the Diaoyutai problem as demanded by militant Baodiao activists was beyond Taiwan’s capability and might even seriously expose the island to the risk of a Communist invasion.131

On March 15, 1971, Ambassador Chow Shu-kai presented a Note Verbale to the US State Department, reiterating Taiwan’s rights to Diaoyutai on the basis of history, geography, usage and law, and demanding that the US respect these rights and return the islands to the ROC before ending its occupation of Okinawa.132

On April 2, Chiang Kai-shek, seeing the US as the key for resolving the sovereignty dispute, telegraphed Chow to negotiate with the US on the Diaoyutai issue.133 On April 12, Ambassador Chow called on President Nixon and National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger for his farewell before he departed for Taipei to assume the post of Minister of Foreign Affairs. Chow asserted that while the Japanese “didn’t care how the Senkakus were administered,” “For the Chinese though, the issue of nationalism was deeply involved.” Not just Chinese students but also scientists, engineers and professionals had participated in the protests on April 10. If Taipei failed to defend Diaoyutai, then the overseas Chinese including the intellectuals would feel that they would have to “go to the other side,” i.e. Beijing.

Kissinger promised to look into the matter further.134 NSC staff member John D. Holdridge prepared a memorandum with his comments on Senkaku Islands for Kissinger to review on April 13. Holdridge’s memorandum stated that the US would return the Ryūkyū and Senkaku islands to Japan in 1972, but would take no position on the sovereignty of the Senkakus, leaving it for the contesting countries to settle. Kissinger wrote this comment by hand: “But that’s nonsense since it gives islands to Japan. How can we get a more neutral position?”135

On June 4, 1971, James Shen, the new ROC ambassador to the US, pleaded for the last time in vain with Assistant Secretary of State Marshall Green for the US to not turn over Diaoyutai together with Okinawa but to treat it as a separate issue.136

The April 12 meetings of Chow with Nixon and Kissinger and the June 4 meeting of Shen and Green illustrated that the ROC had belatedly recognized the serious implications of student activism for the political legitimacy of the KMT, and that Nixon and Kissinger had also been unaware of the gravity of the Diaoyutai issue or the US neutrality principle till the April 12 meeting. The outcome might have been different had the ROC pressed its case in a more formal and urgent manner and brought the issue to the attention of Nixon and Kissinger earlier.

The last hope for the ROC came on June 7, when Ambassador at Large David Kennedy was in Taiwan for negotiations on the textile trade. Kennedy recommended that Washington make a concession to Taipei to break the negotiation impasse, specifically to “withhold turning the Senkaku Islands over to Japanese administrative control under the Okinawa Reversion Treaty.” Kennedy argued that this would induce the ROC to come to an agreement, which in turn would strengthen America’s bargaining position vis-à-vis Hong Kong, South Korea and Japan, the last having engaged in protracted and difficult textile negotiations with the US since 1969. Unfortunately for Taiwan, on June 8 President Nixon agreed with Kissinger’s strong warning on the potentially serious damage to US-Japan relations, and ruled that “the deal has gone too far and too many commitments made to back off now.” On June 17, the US and Japan signed the Okinawa Reversion Treaty, but the US retained the neutrality doctrine, meaning that the return of administrative rights over the Senkakus to Japan would “in no way prejudice the underlying claims of the republic of China.”137

Deepening Factional Divides among Baodiao Activists in the US

The April 10 demonstrations marked a turning point in the Baodiao movement, which split into three directions. A leftist faction identified with the PRC and sought national unification under Beijing. A rightist faction was composed of KMT loyalists strongly committed to anti-Communism, but with some members supporting reform in Taiwan. A middle faction focused on fighting for social justice in Taiwan.138

Disillusionment with the ROC coupled with an idealization of the Cultural Revolution as a progressive transformation led many Chinese in the US to turn to the PRC as sole legitimate government of China. This rosy picture of the Cultural Revolution provided the inspirational ideological foundation and the galvanizing guide to action for Baodiao leftists as they shifted in late 1971 from defense of Diaoyutai per se to working for national unification.139

Why did so many Chinese students, professors and professionals in the US turn to the PRC and even endorse its Cultural Revolution, despite the fact that some were critical of its excesses and atrocities? As Baodiao participant Paul Shui (Shui Binghe 水秉和) explains, for the leftists, “Even though China remained poor, it had developed a selfless, egalitarian, rational new society that surpassed all other countries in the world … They came to perceive Taiwan as a puppet of American imperialism … China was on the road to achieve a utopia through its transformation by the Cultural Revolution.”140 The PRC’s successful nuclear bomb tests and satellite launches and its defiance of the Americans and the Soviets fed the hopes of the overseas Chinese for a strong China. They were heavily influenced by the publications about China they found in their university libraries, including The Selected Works of Mao Zedong, People’s Pictorial, Red Flag, and Edgar Snow’s Red Star over China. Films such as Felix Greene’s documentaries on China and the song and dance epic The East is Red conveyed a positive and stirring picture of China. The thinking of some were also influenced by the intellectual trends of the American New Left, which opposed the American capitalist class oppression of minorities internally and exploitation of the Third World externally, as indicated by Washington’s support of the corrupt government of South Vietnam and its counter-insurgency to suppress people’s liberation movements. Finally, the American New Left idealized China and Cuba as Third World countries that found a self-reliant path to build a just society.141

Students in the leftist faction now doubted the versions of history and understanding of political reality they were taught, and sought answers in library resources of US universities. During the months of May and June, 1971, many Baodiao committees engaged in the study of modern history, organized commemorations of the May 4th Movement, and conducted cultural activities such as the staging of progressive plays and the screenings of PRC films. They also made connections with the Sino-American Friendship Association.142

Between May and September of 1971, many Baodiao action committees were reorganized as study societies for state affairs (guoshi yanjiushe 國是研究社). Between June and October of 1971, Baodiao leftists organized seven regional conferences on state affairs (國是會議), with a focus on problems and issues in Mainland China and Taiwan, and with the number of participants ranging from about fifty to over five hundred.143 The conference at Brown University from August 20 to August 22 was a clear indication of the continuing leftward lurch of many Baodiao activists. The agenda consisted of presentations on and discussions of social and political issues in Taiwan and the PRC.144 About 400 people attended, of whom no more than five were supporters of the KMT government. The conference ended by passing a resolution that the PRC government was the only legal government to represent China, with 118 yes votes, and a single no vote.145

This series of regional conferences culminated in the US Conference on State Affairs (全美國是大會), called by various Baodiao action committees to further discuss and deepen the understanding of social and political conditions in the PRC and Taiwan.146 The conference took place in Ann Arbor from September 3 to 5, 1971. The emerging split between leftists and rightists, with moderates in the middle, became irrevocable there. The organizers had invited all factions to participate, including Taiwan independence advocates and the Third Force (第三勢力) that identified with neither the KMT nor the CCP. James Shen, the ROC ambassador to the US, and Huang Hua (黄华), the PRC Ambassador to Canada, were also invited but did not attend.147

Whether the conference was truly open to different perspectives is a matter of some dispute. Rightists and moderates complained that leftists dominated the agenda and the proceedings. They were dismayed to encounter a highly charged atmosphere, which featured the flying of red flags, the singing of Communist anthems, the glorification of the PRC, and the severe criticism of those who embraced a middle way. Not a single supporter of the Taipei government was allowed to speak from the podium.148 The conference organizers, on the other hand, claimed that everyone who had requested a time slot in advance was accommodated. They countered that those who complained about not getting speaking time failed to contact the organizers before the conference, and only objected after the first day of the conference.149

What is beyond dispute is that most KMT loyalists, about thirty in number, withdrew after the first day. Organizers claimed that they offered those few who stayed to elect a representative to make a presentation, even though they had not requested time in advance. But their offer was not accepted, and consequently, advocates of national unification, Taiwan independence and the Third Force all had opportunities to present their views, but no KMT representative spoke.150