Abstract: This two-part article reconsiders the legacy of Dr. Seuss as presented in the new Dr. Seuss Museum in Springfield, against the author’s little known wartime cartoon representations of the Japanese. It represents important questions about the representation of writers, heroes, even the beloved, in their finest and least memorable moments.

Keywords: Dr. Seuss, Dr. Seuss Museum, PM newspaper, World War II propaganda, cartoons, wartime representations of the “Japs”.

Dr. Seuss, 1940-47, and 2017

Richard H. Minear

The opening of the new Dr. Seuss museum in Springfield—rather, the rededication of one of four buildings in the Museum Quadrangle to Dr. Seuss—has drawn as much attention for what isn’t there as for what is. What isn’t there? Dr. Seuss’s World War II editorial cartoons in the New York newspaper PM,1 his work with Frank Capra on the Why We Fight series, the film Our Job in Japan (1945-6) that was intended to prepare U. S. soldiers for their role in the Occupation of Japan, and his two Oscar-winning documentaries shortly after the war—one on Germany, one on Japan (Design for Death, 1947). Particularly in the editorial cartoons but also in the documentary on Japan, Dr. Seuss descends to racist characterization and analysis.

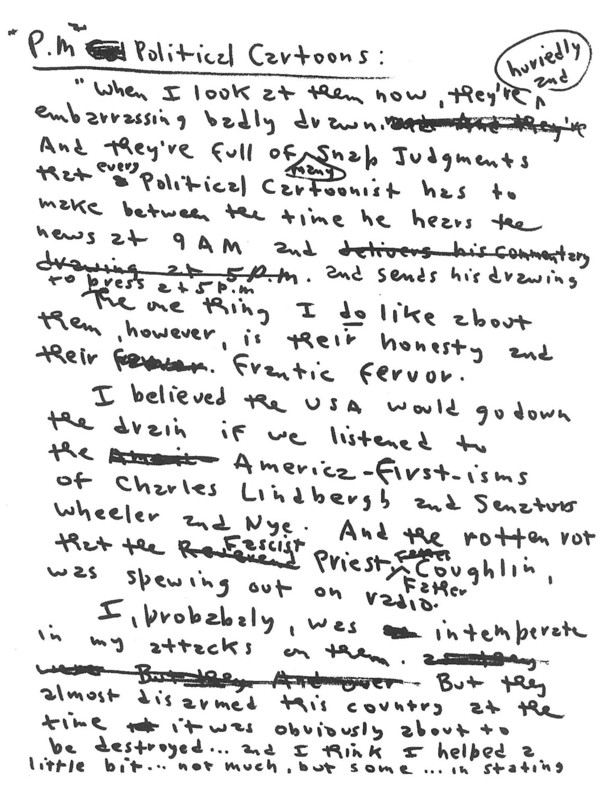

Most notorious is his cartoon of February 13, 1942. It is titled “Waiting for the Signal From Home…,” and it depicts a mass of stereotyped “Japs” marching from Washington and Oregon and California to pick up blocks of TNT from a structure labeled “Honorable 5th Column.” On the roof another “Jap” with a telescope peers out across the ocean.

|

Unlike Dr. Seuss’s Hitler, the “Jap” stereotype that appears, cookie-cutter style, on all these faces was not based on a historical figure—it isn’t Tōjō or the emperor. It may owe as much to Gilbert and Sullivan as to the 1930s. This cartoon appeared days before the Roosevelt administration issued the order to round up all “Japanese” living on the west coast. Many people in audiences to whom I have showed this cartoon start out hoping that it is tongue-in-cheek, but by the time they’ve seen Dr. Seuss’s other cartoons dealing with Japan, most have accepted that this cartoon is what it appears to be.

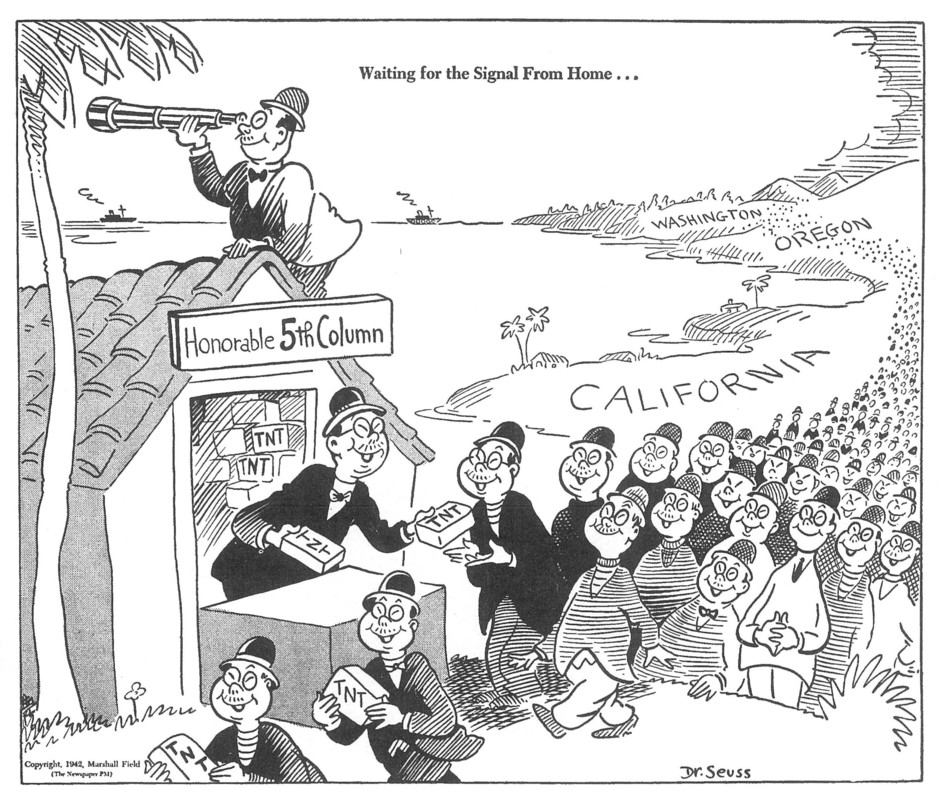

I mention other cartoons. Consider this cartoon of December 9, 1941, just days after Pearl Harbor.

|

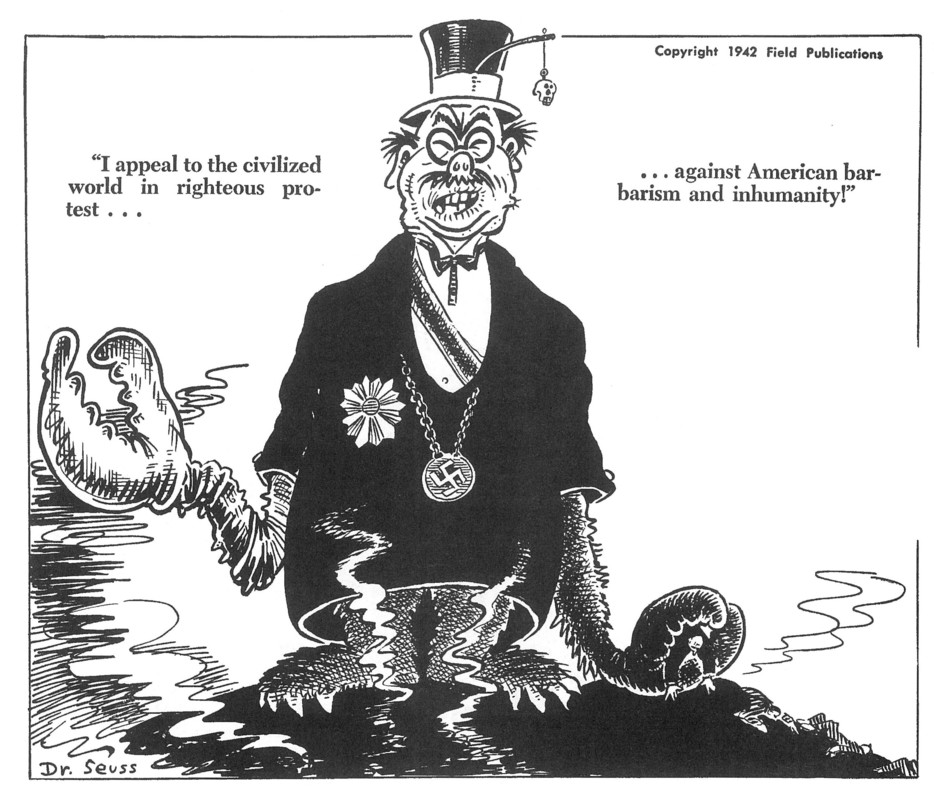

Or consider this cartoon of October 23, 1942.

|

Here Dr. Seuss’s stereotyped “Jap” has arms that end in claws and feet that end in paws. The immediate stimulus was Japan’s execution of three of the airmen it captured from Doolittle’s 1942 bombing raid on Japan.

Why does the new museum omit all this? Reporters noticed at once. Here is one account: “Examples of Geisel’s early advertising work and World War II-era propaganda and political illustrations, many of which critics consider racist, are conspicuously absent, but that’s because the museum is aimed primarily at children, said Kay Simpson, president of the Springfield Museums complex.”2 But here is what Dr. Seuss himself said about his intended audience for the Butter Battle Book, and by extension for all his books: “Practically all my books have been written for every age. Outside of my beginner books, I never write for children. I write for people.”3 What better explanation of the enduring appeal of the books? And of the narrowness of the museum’s focus on children? A second reason, presumably, is that the PM cartoons and the documentaries complicate the loveable narrative of Dr. Seuss.

Why not show that material and invite viewers—people of all ages, including children—to deal with the fact that a man as forward-looking as Dr. Seuss could also have these feet of clay? Forward-looking he was. During the war he took on issues like Black-White racism, and later on he addressed the environment (The Lorax), the Cold War (The Butter Battle Book), commercialism (How the Grinch Stole Christmas), reading for children (The Cat in the Hat, et al.). Even Horton Hears a Who is an allegory on the U. S. Occupation of Japan (Horton=the U.S., Vlad Vladikoff=the Soviet Union, Whoville=Japan) that treats the Japanese with a good deal more sympathy than did the wartime cartoons (much of the condescension, however, remains). But racist against Japanese and Japanese Americans he also was.

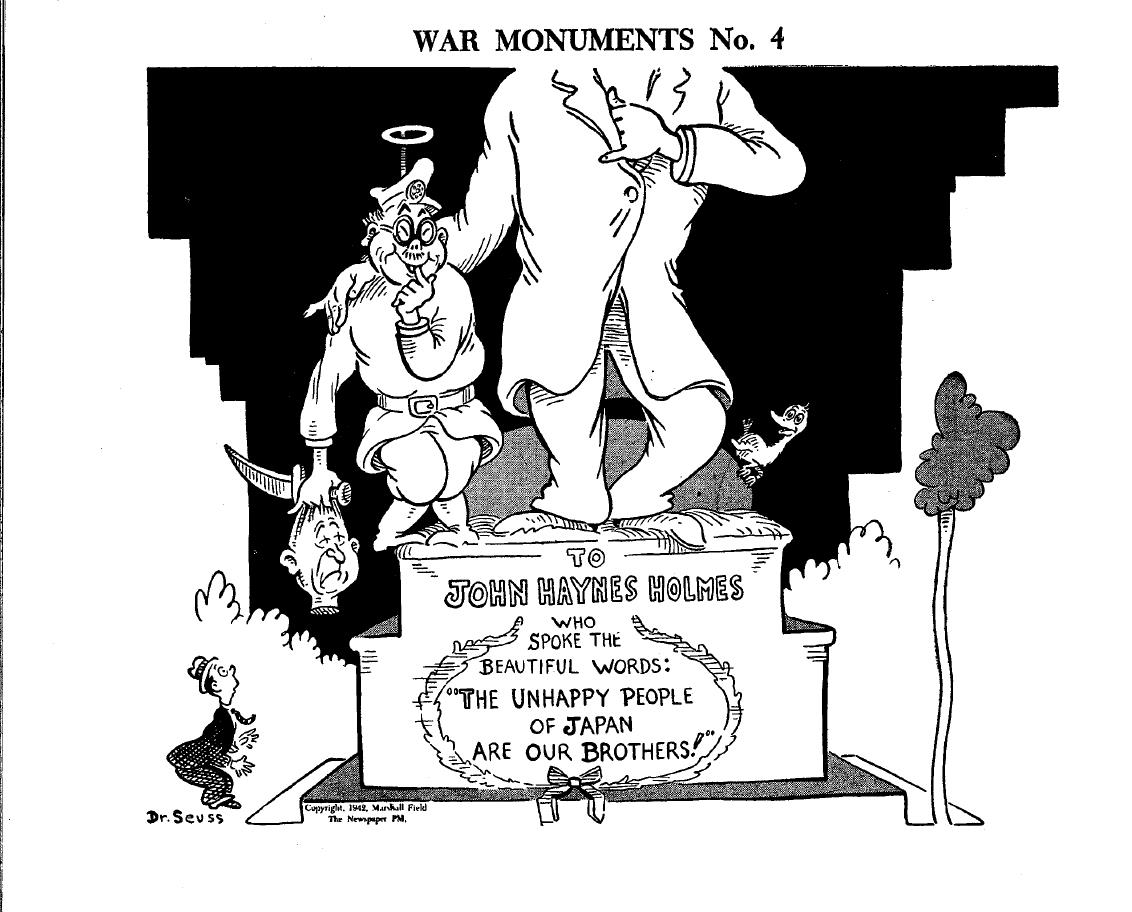

Dr. Seuss rarely stepped out from behind his easel to address such issues. But he did so on two occasions that bear on our present concern. One was in early 1942. On January 13 he published the fourth in a series of heavily ironic “War Monuments.” It showed a statue dedicated to John Haynes Holmes “who spoke the beautiful words ‘The unhappy people of Japan are our brothers.’” Dr. Seuss’s stereotyped “Jap” has a fake halo and holds in his right hand a wicked-looking knife and the severed head of a victim. (John Haynes Holmes was a prominent Protestant pacifist minister.)

|

Readers of PM wrote in to protest—more the treatment of Holmes than of Japan. Wrote one: “I protest the Dr. Seuss cartoon on John Haynes Holmes…. Beyond the sheer bad taste is something even deeper. That is, the implied rejection of the basic Christian principle of the universal brotherhood of man.” Another wrote of “PM’s grotesque incitement to hatred. It’s OK to remember Pearl Harbor; why not remember our war aims, too?”

On January 21 Dr. Seuss responded in his own letter to the editor, which I reproduce here in its entirety:

In response to the letters defending John Haynes Holmes…sure, I believe in love, brotherhood and a cooing white pigeon on every man’s roof. I even think it’s nice to have pacifists and strawberry festivals…in between wars.

But right now, when the Japs are planting their hatchets in our skulls, it seems like a hell of a time for us to smile and warble “Brothers!” It is a rather flabby battlecry.

If we want to win, we’ve got to kill Japs, whether it depressed John Haynes Holmes or not. We can get palsy-walsy afterward with those that are left.

–Dr. Seuss

Contrast that blast with a hand-written follow-up to an interview for the Dartmouth alumni magazine 34 years later, in 1976 (Dr. Seuss was a Dartmouth alumnus). It didn’t become public until an exhibit I organized in the early 2000s at the same building that is now the Dr. Seuss Museum. (Rauner Special Collections Library, Dartmouth College.)

This is Dr. Seuss’s sole late reference to the PM cartoons. He died in 1991. It was only later in that decade that I began to look into the PM cartoons; my Dr. Seuss Goes to War was published in 1999. So I never had the opportunity to ask him specifically about his wartime depictions of Japan and Japanese Americans.

At the Dr. Seuss Museum: Oh, the Places They Don’t Go!

Sopan Deb

|

An exhibition inside the Amazing World of Dr. Seuss Museum, which just opened. Credit: Tony Luong for The New York Times |

SPRINGFIELD, Mass. — Through the front door of the Amazing World of Dr. Seuss Museum in Springfield, Mass., the mind of the beloved children’s book author Theodor Seuss Geisel springs to life. The new three-floor museum is lush with murals, including one with a proo, a nerkle, a nerd and a seersucker, too. Around one corner, visitors will find an immense sculpture of Horton the Elephant from “Horton Hears a Who!”

But the museum, which opened on June 3, displays a bit of amnesia about the formative experiences that led to Mr. Geisel’s best-known body of work. It completely overlooks Mr. Geisel’s anti-Japanese cartoons from World War II, which he later regretted.

Far from the whimsy of “Fox in Socks” (1965), Mr. Geisel drew hundreds of political cartoons for a liberal newspaper, “PM,” from 1941 to 1943, a little-known but pivotal chapter of his career before he became a giant of children’s literature. Many of the cartoons were critical of some of history’s most reviled figures, such as Hitler and Mussolini.

But others are now considered blatantly racist. Shortly before the forced mass incarceration of Japanese-Americans, Mr. Geisel drew cartoons that were harshly anti-Japanese and anti-Japanese-American, using offensive stereotypes to caricature them.

While President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s library has put his role in Japanese internment on full display, this museum glosses over Mr. Geisel’s early work as a prolific political cartoonist, opting instead for crowd-pleasing sculptures of the Cat in the Hat and other characters, and a replica of the Geisel family bakery.

But scholars and those who were close to Mr. Geisel note that this work was essential to understanding Dr. Seuss, and the museum is now grappling with criticism that it doesn’t paint a full picture of an author whose work permeates American culture, from the ubiquitous holiday Grinch to Supreme Court opinions (Justice Elena Kagan once cited “One Fish Two Fish Red Fish Blue Fish”).

“I think it’s irresponsible,” said Philip Nel, a children’s literature scholar at Kansas State University and the author of “Dr. Seuss: American Icon.” “I think to understand Seuss fully, you need to understand the complexity of his career. You need to understand that he’s involved in both anti-racism and racism, and I don’t think you get that if you omit the political work.”

One cartoon from October 1941, which resurfaced during the most recent presidential campaign, depicts a woman wearing an “America First” shirt reading “Adolf the Wolf” to horrified children with the caption, “… and the Wolf chewed up the children and spit out their bones … but those were Foreign Children and it didn’t really matter.” The cartoon was a warning against isolationism, which was juxtaposed with Donald J. Trump, a candidate at the time, using the phrase as a rallying cry.

In another cartoon, from October 1942, Emperor Hirohito, the leader of Japan during World War II, is depicted as having squinted eyes and a goofy smile. Mr. Geisel’s caption reads, “Wipe That Sneer Off His Face!”

Perhaps the most controversial is from February 1942, when he drew a crowd of Japanese-Americans waiting in line to buy explosives with the caption, “Waiting for the Signal From Home …” Six days later, Mr. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which paved the way for the roundup of more than 110,000 Japanese-Americans.

Mia Wenjen, a third-generation Japanese-American who runs a children’s literary blog called PragmaticMom, has written critically of Mr. Geisel’s cartoons and blasted the museum for leaving them out.

“Dr. Seuss owes it to Japanese-Americans and to the American people to acknowledge the role that his racist political cartoons played, so that this atrocity doesn’t happen to minority groups again,” Ms. Wenjen wrote in an email.

|

An exhibition inside the Amazing World of Dr. Seuss Museum, which just opened. Credit: Tony Luong for The New York Times |

One of Mr. Geisel’s own family members, who helped curate an exhibit for the museum, said that Mr. Geisel would agree.

“I think he would find it a legitimate criticism, because I remember talking to him about it at least once and him saying that things were done a certain way back then,” said Ted Owens, a great-nephew of Mr. Geisel. “Characterizations were done, and he was a cartoonist and he tended to adopt those. And I know later in his life he was not proud of those at all.”

Mr. Geisel suggested this himself decades after the war. In a 1976 interview, he said of his “PM” cartoons: “When I look at them now, they’re hurriedly and embarrassingly badly drawn. And they’re full of snap judgments that every political cartoonist has to make.”

He also tried to make amends — in his own way.

“Horton Hears a Who!,” from 1954, is widely seen as an apology of sorts from Mr. Geisel, attempting to promote equal treatment with the famous line “A person’s a person no matter how small.”

At the museum, located amid a complex of other museums in Springfield, where Mr. Geisel grew up, the first floor is geared toward young children. Aside from the murals, there are mock-ups of Springfield landmarks that inspired Mr. Geisel’s illustrations, such as the castle-like Howard Street Armory. The top floor features artifacts like letters, sketches, the desk at which Mr. Geisel drew and the bifocals he wore.

Kay Simpson, president of Springfield Museums, who runs the complex, and her husband, John, the museum’s project director of exhibitions, defended the decision to leave out the cartoons, saying that the museum was primarily designed for children.

“We really wanted to make it a children’s experience on the first floor, and we’re showcasing the family collections on the second floor,” Ms. Simpson said. She said Mr. Geisel’s questionable work would fit better in one of the adjacent history museums, where it has been displayed before.

Susan Brandt, the president of Dr. Seuss Enterprises, which oversees Mr. Geisel’s brand (a brand he resisted commercializing), argued that the museum’s critical distinction is between Dr. Seuss and Mr. Geisel.

Asked why the cartoons aren’t included, Ms. Brandt, who consulted with Ms. Simpson on the museum, replied: “Those cartoons are a product of their time. They reflect a way of thinking during that time period. And that’s history. We would never edit history. But the reason why is that this is a Dr. Seuss museum.” She added, “Those are Ted Geisel, the man, which we are separating for this museum only.”

The museum does, however, have references to some of Mr. Geisel’s early professional work. There is a serving tray on display that Mr. Geisel designed for the Narragansett Brewing Company in 1941 from his days in advertising, for example, and sculptures from the 1930s.

Soon after the opening, the museum expressed a willingness to display the cartoons, perhaps sensitive to criticism that it was presenting a one-sided version of Mr. Geisel, who died in 1991. It invited Mr. Nel to a symposium this fall to discuss Mr. Geisel’s political ideology and Ms. Wenjen to the museum for a visit, something she skeptically referred to as “damage control.”

After all, contrary to Ms. Brandt’s view, the critics argue that it was the work of Mr. Geisel — the man and the political cartoonist — that inspired Dr. Seuss.

“That is the work that made him an activist children’s writer,” Mr. Nel said.

This article, slightly adapted here, appeared in the New York Times on June 21, 2017.

Notes

Richard H. Minear, Dr. Seuss Goes to War: The World War II Editorial Cartoons of Theodor Seuss Geisel (New York: The New Press, 1999) includes two hundred cartoons; for the roughly two hundred cartoons I did not include, see here.

Mark Pratt, “’Oh the Places You’ll Go’ inside the Dr. Seuss museum,” Concord Monitor , June 6, 2017.