|

19 April 1945 |

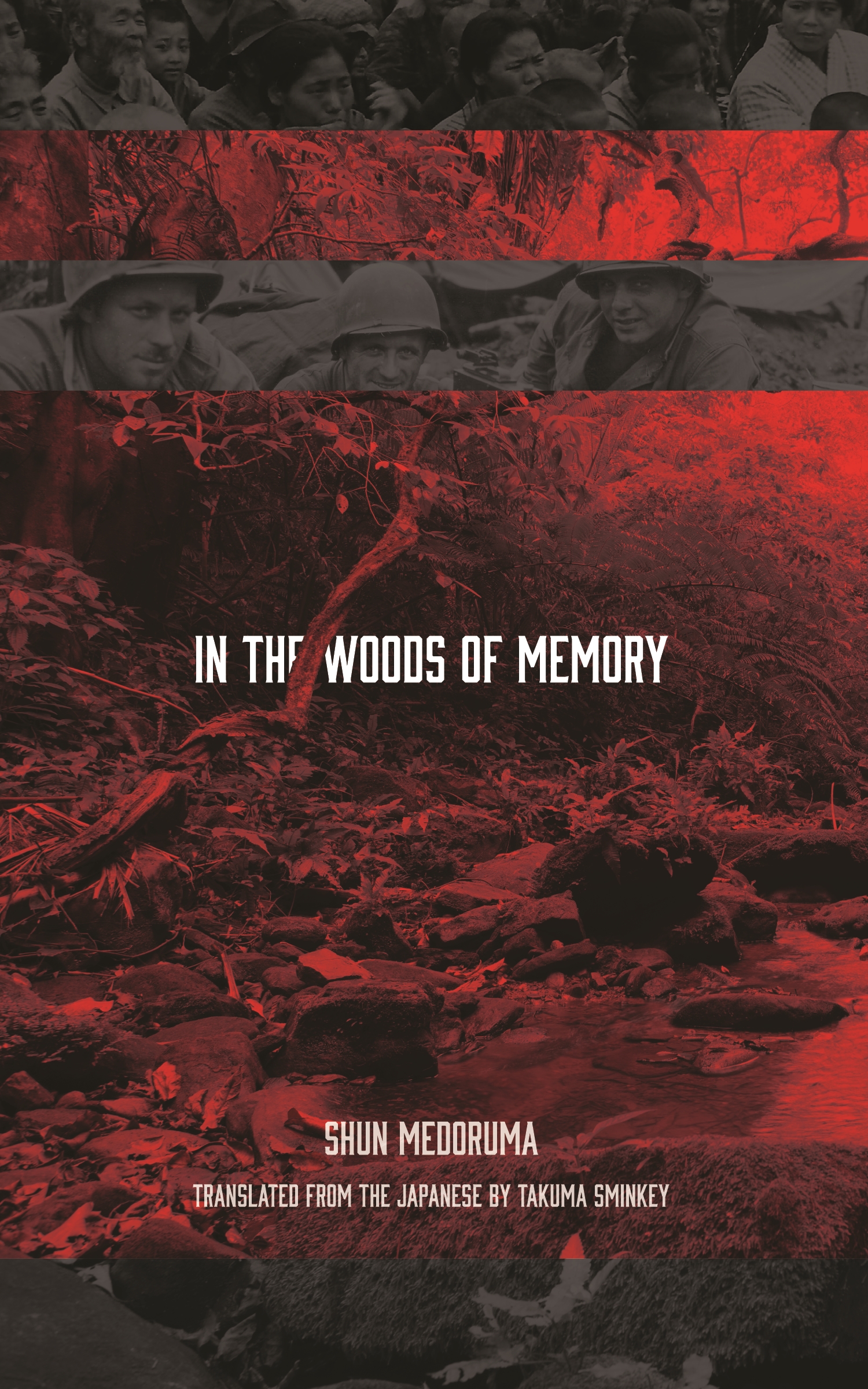

Medoruma Shun and In the Woods of Memory

Abstract: Medoruma Shun, widely recognized as Okinawa’s leading novelist, has published a new novel, translated by Takuma Sminkey as In the Woods of Memory, set in the Battle of Okinawa and on the sixtieth anniversary of the battle. The Asia-Pacific Journal is proud to publish the first chapter of the novel and an introduction to Medoruma’s work.

Medoruma Shunwon Japan’s coveted Akutagawa Prize in 1997 for “Suiteki” [Droplets], a short story praised for its use of magic realism and literary sophistication. Since then, he has won many other literary prizes, and his works have been the focus of books of literary criticism and analysis, both in Japanese and in English.1 Medoruma has also been in the news for his political activism, especially his participation in the protests against construction of the new US military base in Henoko. He was arrested on April 1, 2016, when he paddled his canoe into a restricted area off the coast of Camp Schwab as part of the protest.

Me no oku no mori [In the Woods of Memory] was first published in twelve installments in the quarterly Zenya from Fall 2004 through Summer 2007. After being revised and reorganized into ten chapters, it was published in book form by Kage Shobo in 2009. The novel has received high praise from critics, such as Sadatoshi Ōshiro, who lauds Medoruma for “his powerful use of language in confronting the taboos of memory,” and Yoshiaki Koshikawa, who writes that the novel brings Medoruma “one more solid step toward becoming a world-renowned literary figure.”2 In the Afterword to the English translation, Kyle Ikeda calls the novel “Medoruma’s longest, most complex, and experimentally ambitious war-memory narrative to date.” Personally, I consider the novel to be Medoruma’s masterpiece.

The excerpt that follows is the entire first chapter, “Fumi (1945).” This chapter describes two related incidents that take place on a small island: the rape of a young woman, and a young man’s attempt to get revenge, events that take place in the middle of May 1945, during the Battle of Okinawa. At this point in the battle, US forces had occupied the northern parts of the island, while intense fighting continued to rage in the south. The main setting, though never directly mentioned, is a village on Yagaji, an island just off the northwest coast of the Okinawa mainland. The port at which the US soldiers are working is certainly Unten, located on the mainland directly across from Yagaji. US forces occupied the port early in the battle, long before fighting ended in the south.

In subsequent chapters, the two main stories are narrated, remembered, or considered through various points of view, including those of local villagers and two Americans. Two chapters are set in 1945, while the other eight are set in 2005, the sixtieth anniversary of the end of the war. By retelling the story from various points of view, Medoruma explores how one incident from the war is remembered and passed down to future generations. As Ikeda explains in the Afterword, the novel “explores how survivors of the Battle of Okinawa have lived with unresolved war-related guilt, haunting visions, and trauma that have eluded public disclosure.” The focus of the novel, then, is on how past events have impacted the present.

For Americans—and for mainland Japanese, too—it’s difficult to see the connections between World War II and the present, but for Okinawans, those connections are a daily fact of life. This is partly because of the great costs of the Battle of Okinawa, which involved heavy bombing, group suicides, and large numbers of civilian casualties, nearly one-third of the population. As a result, nearly everyone who experienced the war suffered some degree of trauma. Not only do most Okinawan families have relatives who died in the war; they have relatives who were traumatized, too. In addition, the US military bases scattered throughout the prefecture are a constant and visual reminder of the lingering effects of the war. The negative effects of the base economy, the threats to public safety and health, and the regular occurrence of crimes and accidents have kept the bases on the front pages of Okinawa newspapers practically every day.

Shun Medoruma bases many of his stories on accounts he’s heard from relatives. Although the main plot lines of In the Woods of Memory are fiction, they draw on various real-life incidents. In a May 8, 2016 interview published in the Okinawa Times, Medoruma said that the rape was based on a story he heard from his mother, who lived on Yagaji during the war. He also discusses the incident in one of his collections of essays.3 There are also parallels to the infamous 1995 Okinawa rape incident, in which three US servicemen raped an elementary school girl.

The revenge plot also has resonances with the 1945 Katsuyama killing incident, in which Okinawans from a village near Nago murdered three US Marines in retaliation for raping village women shortly after the Battle of Okinawa. Medoruma’s descriptions of prewar education, the relocation of civilians, detention camps, and the role of interpreters during the war are all accurate.

For more information about Okinawa literature, including a reading guide for In the Woods of Memory, see my website, Reading Okinawa.

This is an abbreviated and revised version of the “Translator’s Preface,” from In the Woods of Memory (Stone Bridge Press, 2017).

|

May 1945 |

Fumi (1945)

—The Americans are coming! Hisako called out in alarm.

Fumi was searching for shellfish on the seabed and could feel the waves swirling between her legs. She raised her head and looked where Hisako was pointing. At the recently constructed port on the opposite shore, a dozen American soldiers were working. Perhaps because their jobs were done, several had tossed off their clothes and were diving into the ocean. One soldier was already swimming toward Fumi and her friends. He had a considerable lead by the time the other three stopped shouting and started diving in after him.

It was only about two hundred meters from the opposite side, and since the small northern island running parallel to the main Okinawan island formed a narrow passageway, the sea was peaceful. Local fishermen called the inner passage “the bosom,” and whenever typhoons threatened, they fled here from the high seas for safe haven. During spring tides, the current was dangerous, but at other times, even children could swim to the other side.

Along with Hisako and Fumi, three other girls were searching for shellfish in the shallows: Tamiko and Fujiko, their fourth-grade classmates, and Sayoko, Tamiko’s seventeen-year-old sister. Only Sayoko seemed worried about the approaching soldiers and uncertain whether to flee to the village. She called to Tamiko and the others, but the girls merely edged closer to shore and went on with their work.

Fumi wasn’t scared of American soldiers anymore.

Before the war, her teacher had told them horrifying stories about how after catching you, the Americans would gouge out your eyes, slit open your belly, and butcher you like a goat—even if you were a child. Never let yourself be captured, they were told; better to commit suicide than be taken prisoner. One boy had asked how they should kill themselves, but the teacher avoided specifics and said that when the time came, the adults would tell them how to die.

Fumi couldn’t imagine herself dying, so being told to take her own life didn’t scare her. However, an intense fear of American soldiers had been planted in her heart. Some of the boys had enjoyed scaring the girls by describing how American soldiers ate children’s livers or kidnapped women and carried them off to America. As a result, when the war started and some American soldiers found Fumi and her family hiding in a cave in the woods, she felt weak in the knees and couldn’t move. A dozen other families from the same village were also in the cave. Fumi was with her grandparents, her mother, and her two younger brothers, aged seven and four. Her father and older brother weren’t with them because they’d been conscripted into the Defense Corps, the local militia.

As Fumi rode piggyback on her grandfather down the hill through the woods, she covered her face with her hands, so she wouldn’t see the American soldier walking beside them. When he tapped her on the shoulder and tried to hand her something, she flinched, turned away, and clung to her grandfather. The villagers were rounded up in the open space used for festivals. Fumi thought that that’s where they’d all be killed.

After her grandfather set her down, she and her terrified younger brothers clung to the hem of her mother’s kimono and watched what was happening. A soldier who could speak Japanese was going around and writing down the names of everyone in each family. The soldiers on the perimeter had rifles slung over their shoulders, but they didn’t point them at the villagers; they just stood around smoking and chatting in groups of twos or threes. Some of the soldiers offered cigarettes to the older villagers, but nobody accepted. Others tried to hand something that looked like candy to the children, but all of them refused—and hid behind their mothers.

When a truck arrived about an hour later, Fumi and her family were loaded on the back and taken to an internment camp set up in another village on the island. Over the several weeks they spent there, Fumi’s fear of American soldiers turned to familiarity.

Far from harming the camp residents, as her teacher had warned, the soldiers gave them food and cared for the sick and wounded. Residents from all six villages on the island were put in the same camp, and by the time Fumi and her family arrived, about four hundred people were already living there in large tents or the houses that hadn’t burned down. Some villagers were returned émigrés from Hawaii who could speak English; together with the American interpreter, they explained the rules and routines of the camp to the newcomers.

After Fumi and her family were given simple medical exams and dusted with a disinfectant powder, two American soldiers and a male returnee brought them to the tent where other families from their village were living. Here, for the first time in her life, Fumi tasted chocolate, which was handed to her by a Caucasian soldier about twice as big as her father. She never imagined anything could taste so delicious. Most of the American soldiers were fond of passing out sweets. Within a few days, Fumi was continually pestering them—just like all the other children.

A soldier named Tony often showed up at Fumi’s tent, perhaps as one of his duties. He was fond of Fumi and always brought chocolate and canned food. When Fumi sang for him, Tony sat on the ground and listened with great pleasure. One of the village men who could speak some English explained that Tony was twenty-one and had a sister about Fumi’s age.

Whenever the boys in the camp saw Tony, they would laugh and jeer:

—Tani, Tani! Magi Tani!

Tony, who couldn’t possibly have known that in Okinawan tani meant “penis” and magi meant “big,” always turned to the boys with a friendly smile. Fumi was furious, but too embarrassed to say anything.

The Japanese forces on the island had abandoned their positions along the coast even before the Americans had intensified their bombing. Retreating to higher ground, they entrenched themselves in the caves scattered throughout the woods of the island, only ten kilometers in circumference. Ten days after the American landing, they lost the will to fight and surrendered.

The islanders had diverse views of the Japanese soldiers, who were confined in a separate part of the camp. Some looked upon the emaciated, unshaven figures with sympathy; others scorned them for having spoken with such bravado, only to have been so easily defeated and taken prisoner. Fumi couldn’t have cared less; she was just happy to be alive.

The one thing that weighed on Fumi’s mind was the fate of her older brother. Her father was reunited with the family in the camp, but they had no idea what had become of her brother, who had moved to the main Okinawan island with the Japanese army. The war in the northern half was over, but in the south, a fierce battle raged on, day after day.

After about a month in the camp, Fumi and her family returned to their village. Forbidden to leave the island and relying on supplies provided by the Americans, the villagers struggled to rebuild their lives. School hadn’t resumed yet, but Fumi worked busily all day long: helping in the fields, taking care of her younger brothers, gathering firewood, collecting shellfish, and assisting her family as best she could.

On her first trip to the beach after returning to the village, Fumi was shocked to see how greatly things had changed on the opposite bank. A pier had been built on a reclaimed rocky stretch, and several large warehouses stood where once there’d been a thicket of screwpine trees. Small American military transport ships moved in and out frequently, and trucks spitting black smoke carried off the unloaded supplies. Many soldiers tossed off their drab green shirts and worked stripped to the waist. Their red, white, black, and brown bodies were starkly visible, even from a distance. At night, lights burned brightly, making it seem that a mysterious world had appeared magically across the water.

Since Fumi watched the port while collecting shellfish every day, she had grown accustomed to the Americans and their actions. It wasn’t unusual for soldiers to jump into the ocean and go swimming. And today probably wasn’t any different. Fumi figured that they were just seeking relief from the heat. So she ignored them and focused her gaze below the surface. In the shallows close to shore were mostly small cone snails. If she moved further out, she could find large horned turbans or giant clams wedged into rocks. But she wasn’t allowed to go there unless accompanied by an adult.

Completely absorbed in her work, Fumi raised her head in surprise when she heard the voices of American soldiers nearby. They had already swum across and were now talking loudly as they came walking toward her. At the water’s edge, about thirty meters away, Tamiko, Hisako, and Fujiko were gathered around Sayoko and beckoning Fumi to return. Apparently, they had been calling for some time, but Fumi had been absorbed in her search and hadn’t noticed. She looked into the bamboo basket hanging from her shoulder. It wasn’t full yet, but she knew she’d better join Sayoko and the others.

As she hurried to shore, Fumi was careful not to step on any coral or rocks. Though flustered at not being able to move faster, she soon reached the shallow water where the waves lapped against her calves. The American soldiers were right behind her. Sayoko hugged the girls close, her eyes darting back and forth between Fumi and the soldiers. Fumi could tell that Sayoko was terrified. The sense of panic had infected her three classmates, and she could feel her own heartbeat quickening as she splashed through the water.

One of the American soldiers passed Fumi just before she came ashore. Sayoko tried to move up the beach to the path leading to the village, but the soldier got ahead of her, blocking her way. Fumi gazed past Sayoko to get a better look. She had never seen him before. He was white and had tattoos on both arms. His sunburned chest was covered with blond hair, and he wore nothing but a pair of trunks. His frenzied mood and expression, so different from Tony’s friendly demeanor, was deeply unsettling.

The soldier grinned and said something to Sayoko, who didn’t understand English. Sayoko pushed the other girls ahead of her and tried to slip past, but the soldier suddenly grabbed her arm. Sayoko’s scream rang out across the beach. The soldier pulled Sayoko close and put a hand over her mouth. She struggled to break free, but then another soldier ran up and grabbed her legs. As the two soldiers carried Sayoko off into the thicket of screwpine trees, Fumi and her classmates screamed and gave chase.

Crying, Tamiko was reaching out toward her sister when a soldier grabbed her by the arm and flung her to the ground. Spitting out sand, she coughed twice and moaned. Fumi clutched at still another soldier. At first, he just held her back, a look of dismay on his face. But when she sunk her teeth into his hand, he yelled and shoved her away. As Fumi fell backward, she saw another soldier slap Fujiko and Hisako and send them flying. The four girls ended up sitting on the beach, unable to do anything.

The soldier that Fumi had bitten stood in silence and looked back and forth between the girls and the screwpine thicket. The other soldier moved around restlessly, punching his open palm with his fist, and muttering to himself. When Tamiko started sobbing, he yelled angrily in her ear and punched her in the face. The other soldier rushed in to stop him. After that, there was no more violence. Even so, the girls huddled together and were too terrified to speak or cry. Screams, groans, and the sounds of punches could be heard from the thicket. With each noise, the girls flinched, hugged each other, and prayed that Sayoko wouldn’t be killed. What their teacher had told them before the war turned out to be true, Fumi thought. Today, the soldiers would kill them.

When the two soldiers returned from the thicket, they traded places with the two soldiers on the beach. One headed toward the thicket slowly; the other shouted with glee and dashed over. The two that had returned lay down in the sand, propped up on their elbows, and shouted comments toward the thicket.

Before long, the second group of two soldiers returned to the beach. The four exchanged some words, entered the ocean, and began swimming back toward the port. The sun had already sunk behind the warehouses on the opposite bank, and nightfall was approaching. When the soldiers had got about twenty meters from shore, Tamiko was the first to get up and run toward the thicket. Fumi and the other two girls followed.

—Stay away! a voice called out from within the thicket.

Fumi and the other girls stopped and looked into the shadows of the thorny-leaved screwpine trees. In the dim light, they could see Sayoko squatting and hugging her naked body. Fumi still didn’t understand what went on between men and women. But she knew in her bones that Sayoko had not only been kicked and beaten but had suffered a profound violation of her body and soul.

—They didn’t hurt you, did they? Sayoko asked the four girls, who were standing transfixed.

Then she told Tamiko to call their mother, adding that she shouldn’t forget to bring some clothes. While Tamiko ran to the village and returned with her mother, Fumi and her classmates could only stand there in silence.

That night, the account of the attack on Sayoko spread through the whole village. After supper, Fumi was told to take her brothers to the back room. Meanwhile, her parents and grandparents spoke in whispers in the front room. Then, her father and grandfather went out together and didn’t return until late at night. Before they returned, Fumi’s mother warned Fumi that she should never go to the beach or the woods alone, and that if she ever saw an American soldier, she should run home right away.

***

From the next day, the entire village was under a heavy strain. Young women hid in the back rooms of their homes, and men took turns standing at the beach and on the roads leading into the village. A bell, made by removing the gunpowder from an unexploded shell, was hung from the giant banyan tree in the open space where the priestesses prayed to the guardian gods of the village. As the villagers worked in the fields or in their homes, they were constantly on edge, thinking the bell would ring at any moment.

In the afternoon, Fumi asked Fujiko and Hisako to go to the woods to gather firewood. She couldn’t ask Tamiko because she had been confined to her house since morning. After being joined by three other girls about their age and some boys who were going to gather grass for the goats, they headed to the woods, located about two hundred meters from the village. Fumi and her friends were picking up dead branches under a large pine tree, not too far into the woods, when suddenly the bell rang out. Struck by the sound of the fiercely ringing bell, the children dropped what they were doing and prepared to run to the village. As they were hurriedly picking up their firewood and grass, one boy yelled:

—Forget that stuff! You can get it later!

It was Chikashi, a boy one grade ahead of Fumi. Everyone threw down what they were holding and dashed off to their homes at full speed.

When they got back to the village, Fumi saw a US military jeep parked near the giant banyan tree. Four of the five soldiers standing around the jeep were the men from the day before. As the children arrived, their parents came running up and hugged them. Hurrying home with her mother, Fumi noticed her father and about twenty other men from the village standing in a circle in the clearing.

The heavy front door to their home was locked from inside, so they went around to the kitchen door in the back. As soon as they entered, Fumi’s mother locked the door and led Fumi to the front room to join her grandparents and younger brothers. Fumi’s grandmother was fervently praying in front of the family’s Buddhist altar. When their mother sat down behind their grandmother, Fumi’s younger brothers clung to her. Fumi went up to her grandfather, who was looking outside through a crack in the door. Fumi peered through a knothole and watched, too.

The men from the village were staring in wary silence at the American soldiers. Two of the five soldiers had rifles slung over their shoulders, so the men couldn’t move. Standing next to the jeep, the soldiers were smoking and passing around a bottle as they watched the men. Before long, the soldiers started to move. The armed soldiers pointed their rifles at the men from the village, and the other three soldiers disappeared. After a couple minutes, Fumi could hear the sound of a door to a house being kicked down. Then she heard the screams of the residents. Even then, the village men dared not move.

Her mother called, so Fumi had to stop watching. She hugged her younger brothers and cringed. Would their door be kicked down next? The soldiers terrorized the village for about an hour, but Fumi’s house was spared. When her father called from outside, her mother hurriedly slid the door open.

—What happened? Fumi’s grandfather asked.

In silence, her father pushed the door open the rest of the way. Standing at the entrance, he drank the tea Fumi’s mother brought him. Then he picked up the hoe and straw basket sitting outside the door and headed back to the fields. The tormented look on his face as he put down his teacup was something Fumi had never seen before.

Fumi’s father wasn’t the only one with such a look. The next day, every man in the village, young and old alike, had the same tormented expression. The day before, right before their very eyes, the American soldiers had raped two young women. When Fumi overheard the adults whispering about this, she thought that her house would surely be next. Even with their doors closed at night, she couldn’t sleep. Other than her two brothers, no one else in her family could sleep either.

After the second incident, the American soldiers didn’t show up for a while. But the strain on the villagers didn’t lessen in the least. Everyone looked exhausted, conversation decreased, and laughter ceased entirely. The men were kept busy patrolling the area, so fieldwork and repairs of the damage from the war fell behind. Fumi and her friends had to limit their movement to areas where they could quickly run back to the village. They could no longer go to the ocean to collect shellfish, but they could still cut grass for the goats or collect firewood.

Four days later, Fumi was working along the western edge of the woods. Though the boys and girls usually went their separate ways, Fumi stayed with the boys to pick up firewood. She was nervous about being so far from the village, but since they could clearly see the American port from the cliff facing the ocean, they figured they’d be okay. To be safe, they took turns keeping lookout.

About five minutes into her shift, Fumi spotted a dozen soldiers resting in the shade of a warehouse. Apparently, they’d finished unloading the freight and were taking a rest. Suddenly, four of them stood up and began taking off their work clothes. Fumi strained her eyes to see what they’d do next. When she saw them walking along the pier in their trunks, she called to Chikashi, who was nearby. Just as he came to her side, they saw the four soldiers diving into the ocean, one after another.

—The Americans are coming! Chikashi yelled to the others.

The other children frantically dashed off toward the village, but Fumi and Chikashi stayed where they were, entranced by the sight before them. Immediately after the soldiers dove off the pier, they spotted a young man on the rocks at the bottom of the cliff running toward the ocean with a harpoon. He wore nothing but a loincloth. As soon as he stepped into the water, he tied the cord attached to the harpoon to his waist and began swimming out to sea. Fumi and Chikashi knew they should return home, but their eyes were riveted on the young man.

—It’s Seiji, Chikashi muttered.

Seiji was the boy who lived next door to Sayoko. Due to the glare of the setting sun reflecting off the water, they could only see the heads of the Americans, but Seiji was still close, so they could clearly see him moving through the water, with his harpoon dragging behind. Using a smooth breaststroke, Seiji circled around the soldiers until they were about halfway across the passageway. Then he changed course, moved into the ocean’s current, and closed in at a speed about twice as fast as before.

The soldiers noticed Seiji when he was about thirty meters away. They treaded water and stared at him for a while, but then resumed their crawl strokes and continued heading toward the island. Seiji switched to a crawl stroke, too. When he was within four or five meters of the soldier taking up the rear, he dove beneath the surface.

From the top of the cliff, Fumi and Chikashi watched with bated breath as Seiji glided through the clear water. As he passed beneath the soldier, he reeled in the cord tied to his waist and took the harpoon in hand. Then he thrust upward and shoved the harpoon into the man’s stomach. The man screamed and frantically tried to swim away. A second later, Seiji popped up out of the water and hurled the harpoon at the man’s back. But this time, he missed.

One of the other soldiers swam over to help their wounded friend, and the other two swam at Seiji, who raised his harpoon to confront them. When one of them lunged at him, Seiji stabbed him in the shoulder. Fumi could hear the man’s scream even from the distance. The soldier latched onto the harpoon, and even though he was bleeding, refused to let go. Then the other soldier swam toward Seiji. A sudden flash of light revealed a knife in Seiji’s hand. As the weapon swung down, the soldier dodged and dove into the water. Next, Seiji waved the knife at the soldier bleeding from the shoulder. When the soldier let go of the harpoon, Seiji turned around and began swimming toward the island. The soldier that had been fended off with the knife resurfaced and started to give chase, but after swimming twenty meters or so, he apparently realized he’d never catch up and returned to his friends.

The soldier who’d been stabbed in the stomach floated on his back with the help of one of his friends. Then the man who’d been stabbed in the shoulder joined them and helped, too. Meanwhile, the man who had chased Seiji swam toward the port and began waving and yelling for help. The soldiers at the port noticed that something was wrong and sprang into action. Seiji swam as fast as he could toward the island. He reached the rocks below the cliff before a rescue boat had even been launched from the port. After coming ashore, Seiji cut the cord tied to the harpoon and picked up his clothes, hidden near a rock. Then he dashed off along the rocks with his harpoon and clothes and disappeared into a thicket of trees.

Transfixed, Fumi and Chikashi had watched the whole scene from beginning to end. When they could no longer see Seiji from the top of the cliff, they became frantic about getting to safety. The bell in the village had been ringing for quite some time.

—Let’s get going, Chikashi said.

Then he grabbed Fumi’s hand and started running. Too panicked to feel embarrassed, Fumi squeezed the older boy’s sweaty hand and ran as fast as she could. When they entered the village, they let go of each other’s hands and ran off to their respective homes. As Fumi dashed past the banyan tree, she saw about a dozen men from the village with sticks and hoes.

—You’re late! scolded Fumi’s mother when Fumi entered their yard.

From outside, Fumi could see her grandmother praying before the family altar. Fumi’s brothers were kneeling behind, giggling and mimicking her. Fumi’s grandfather, who’d been waiting in the yard, closed the front door behind Fumi as they entered the house. Fumi told her mother about what she’d witnessed. After hearing Fumi’s account, Fumi’s grandfather immediately dashed off to notify the other men. Fumi’s grandmother intensified her chanting, and the two boys stopped smiling. When Fumi saw the terrified look in their eyes, she went over and hugged them and patted them on their backs.

The Americans showed up about half an hour later. Arriving in several jeeps and small trucks, the group of about twenty soldiers disembarked and readied their rifles.

—Throw down your weapons! the interpreter screamed at the thirty men gathered near the banyan tree.

The men hesitated, but then did as they were told. The interpreter was a man of Japanese descent in his mid-twenties. He ranted on about something, but Fumi couldn’t understand what he was saying. They’ve come to get Seiji, she thought. She could tell that the men were growing more and more upset as they listened.

The soldier in charge said something to the interpreter, who then screamed at the village men. The men exchanged glances and started talking, but the interpreter yelled at them to be quiet. The squad leader gave an order, and the soldiers started moving. At the interpreter’s command, the village men followed.

The Americans started searching the houses in the village. When Fumi saw five soldiers coming toward her house, she ran to her mother and clung to her. There was a violent knocking at the front door, and Fumi’s grandfather hurried to open it. The soldiers entered their house without even taking off their boots and spoke loudly as they searched every room. After they’d finished searching the pigsty outside and every nook and cranny of the small yard, they moved on to the next house. Terrified by the intrusion, Fumi’s grandfather knelt in the middle of the front room with his head hanging down. Fumi trembled in fear and buried her face in her grandmother’s bosom.

Nobody left the house until Fumi’s father returned after dark. Fumi listened in on his conversation with her grandfather and found out what the Americans were doing. The soldiers had been divided into two groups: a group of about ten was searching the houses, one by one, while the other group was searching the surrounding woods. In the meantime, the leader and the interpreter were at the banyan tree questioning Seiji’s parents, the ward chief, and the head of civil defense. They were determined to find out whether Seiji had acted on his own or as part of a group.

The village men had been forced to help the soldiers search the woods. Of course, they just pretended to cooperate, while secretly hoping that Seiji would escape. However, there were a limited number of places to hide, so if the Americans called in more men, they’d be sure to catch Seiji within two or three days. Everyone felt that his only way to escape was to swim across to the main island. But small US warships were constantly patrolling the area, so it wouldn’t be easy to get across undetected. Besides, as Fumi’s grandfather pointed out, they’d probably stationed troops along the shorelines.

Fumi’s father mentioned that Seiji’s parents were completely terrified. Seiji’s mother had been crying and saying that the Americans would kill her son if they caught him. Seiji’s father had seemed to doubt whether their son could’ve done what he’d been accused of. The other men were surprised, too. Seiji was only seventeen, and even though he’d been toughened up from his work at sea, he still had a boyish face. Compared to his violent father, Seiji was meek and mild. No one could believe that the weak boy who’d been bullied to tears as a child had stabbed an American soldier with a harpoon. But according to his parents, Seiji had been away from home since early afternoon, and his prized harpoon was missing.

As for the American soldiers, the one stabbed in the shoulder appeared to be fine, but the one stabbed in the stomach was in critical condition. One of the four had remembered Seiji from the internment camp, and the Japanese-American interpreter knew that Seiji had been in the Defense Corps and worked with the Japanese army.

—He’s still just a child, isn’t he? said Fumi’s father.

Fumi couldn’t tell if he spoke in admiration or in annoyance.

—Well, I didn’t see the adults do anything, said Fumi’s grandfather.

The comment caused Fumi’s father to fall silent.

That night, the Americans set up a large tent near the banyan tree. A searchlight powered by a generator was trained onto the houses. The soldiers patrolled the village in pairs, while a soldier with a rifle stood at the tent on night duty. With the droning sound of the generator echoing through the village, and the intermittent footsteps and voices of soldiers, Fumi couldn’t sleep.

A full-scale search started early the next morning. Just like the day before, the men of the village were forced to cooperate. The women and children felt uneasy about the presence of the Americans, but they couldn’t stay locked up inside all day. If they didn’t tend to the crops, draw water, and cut grass for the goats, they’d have no way to live.

During her many trips to the spring to fill her family’s water jar, Fumi wondered whether the American stabbed in the stomach would survive. She pictured the red blood spreading through the clear greenish-blue water and the wounded soldier holding his stomach. She assumed that Seiji would be executed if the soldier died. She also pictured Seiji coming ashore and dashing across the rocks with his harpoon. Where was he hiding? And did Sayoko hear about what he’d done?

Since the attack at the beach, Sayoko and Tamiko had stayed confined in their home and hadn’t shown their faces. Their parents worked in the fields, but no one dared ask about Sayoko. Fumi quickened her steps whenever she passed Tamiko’s house. When she pictured Sayoko and Tamiko in the back room, her throat tightened, her breathing became labored, and her eyes filled with tears. During the search the day before, the Americans must’ve entered Sayoko and Tamiko’s house, too. How did the two girls react when the soldiers threw open the door, entered the house in their boots, and started yelling?

When her mother called, Fumi realized that she’d been daydreaming. She picked up the water jar and started to head home. For some reason, the villagers were filing out of their homes and heading toward the woods.

—The Americans, explained Fumi’s mother, threw poisonous gas into the cave where Seiji’s hiding.

Then she stared into the distance with a terrified look. Fumi’s knees shook and she grew restless. Taking her mother’s hand, Fumi headed to the woods with the other villagers to witness what was happening.

Related Articles

• Takazato Suzuyo, Okinawan Women Demand U.S. Forces Out After Another Rape and Murder: Suspect an ex-Marine and U.S. Military Employee

• Masako Shinjo Summers Robbins, with an introduction by Steve Rabson, My Story: A Daughter Recalls the Battle of Okinawa

• The Ryukyu Shimpo, Ota Masahide, Mark Ealey and Alastair McLauchlan, Descent Into Hell: The Battle of Okinawa

• Michael Bradley, “Banzai!” The Compulsory Mass Suicide of Kerama Islanders in the Battle of Okinawa

• Sarah Bird with Steve Rabson, Above the East China Sea: Okinawa During the Battle and Today

• Yoshiko Sakumoto Crandell, Surviving the Battle of Okinawa: Memories of a Schoolgirl

• Aniya Masaaki, Compulsory Mass Suicide, the Battle of Okinawa, and Japan’s Textbook Controversy

Notes

For a critical analysis of Medoruma’s work in English, see Kyle Ikeda, Okinawa War Memory: Transgenerational Trauma and the War Fiction of Medoruma Shun (Routledge, 2014). For an analysis of his work in Japanese, see Susan Bouterey, Medoruma Shun no sekai [The World of Medoruma Shun] (Kage Shobo, 2011), and Tomoyuki Suzuki, Me no oku ni tsukitaterareta kotoba no mori [A Harpoon of Language Thrust into the Eye] (Shobunsha, 2013).

For Ōshiro’s review of Medoruma’s novel, see “Kioku e chōsen suru kotoba no chikara” [The Power of Language Confronting the Limits of Memory], Ryūkyū Shinpō, 23 August 2009, page 22. For Koshikawa’s review, see Shōsetsu Torippā, Winter 2009, pages 434-6.

For Medoruma’s discussion of the incident, see Okinawa “sengo” zero nen [Zero Years After the “End” of the Battle of Okinawa] (NHK Press, 2005), page 59.