Benedict Anderson reminds us that modernity has been characterized by the emergence of nation-states that can mobilize the passion of young men to “die for the country” on a mass scale.1 Once mobilized, nationalist passion allows a soldier to believe “he is dying for something greater than himself, for something that will outlast his individual, perishable life in place of a greater, eternal vitality.”2 But after demobilization, this patriotic fervor withers, no longer fed or needed for everyday combat. In peacetime, the fervor that enabled death and destruction for national purpose no longer even has any social or moral legitimacy.

After modern wars that called up millions of conscripts, the tension between repudiating or lamenting the violent destructions of war and seeking something meaningful in the same violent destructions has been unresolvable. This tension is especially acute in defeated nations where, as Wolfgang Schivelbusch asserts, the desire to search for positive meaning in the national failure is a common and powerful need.3 The impulse to generate positive meaning from defeat often gives over to narratives such as the myth of the Lost Cause among the American Confederacy after the Civil War, and the myth of the Fallen Soldier in Germany after World War I.

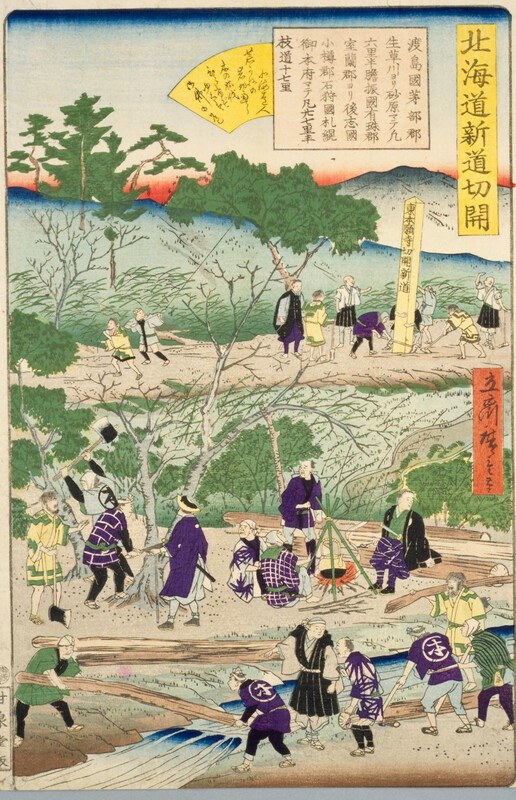

The difficulty of overcoming devastating defeat lies at the root of Japan’s struggle to define its political culture and identity seven decades after the end of World War II. As I show in my book The Long Defeat: Cultural Trauma, Memory and Identity in Japan (2015), how Japan reckons with this national trauma is crucial to understanding its contentious politics today. From disputes over revising the peace constitution to expanding military capabilities and increasing Japan’s global military role, different visions for Japan’s political future have clashed for many decades; they continue to clash in different arenas as we see today in the government’s swing to the right, and its declared intention to revise the peace constitution after dominating the 2016 upper house election. Characteristically, this contentious politics stirs up fierce passion on all sides precisely because “something much greater than ourselves” is at stake. In this context, Japan faces three broad choices for national policy and moral purpose in moving forward: nationalism, pacifism, and reconciliation.

Three Paths Forward beyond the Culture of Defeat

The three paths forward that I identify — nationalism, pacifism, and reconciliation — are preoccupied with different concerns and visions for Japan’s future. They espouse different understandings of Japan’s war, and propose different approaches for bringing closure to the long defeat. Similarly motivated by deeply engrained memories of humiliation, they nevertheless differ profoundly in their strategies to recover from them. These paths are embraced today to different degrees by different stakeholders, from state and business leaders to religious and civic groups, public intellectuals, political networks, social activists, and transnational movements. Ultimately they represent different approaches to repair the moral backbone of a society that has yet to effectively come to grips with the trauma of empire, war, and defeat.

In broad outline, the three paths can be described as follows. (1) The nationalist path is deeply concerned with erasing the stigma of defeat, and envisions a strong Japan to be reckoned with in the world. The proponents desire above all to enhance Japan’s power, wealth, prestige, and respectability, which align with Japan’s long-standing quest to stand shoulder to shoulder with world powers. (2) The pacifist path, on the other hand, is concerned with overcoming defeat by becoming a moral nation respected in the world for its principled commitment to non-violence. Its proponents seek to enhance Japan’s moral standing against human suffering which aligns with a radical anti-military credo deeply ingrained in postwar popular sentiments. (3) Finally, the reconciliationist path differs from the first two in striving to inscribe Japan’s dark past in national history, and build a contemporary identity based on regional reconciliation and integration. The proponents of reconciliation want Japan to earn the world’s respect by developing solidarity with former adversaries, based on goodwill and responsibility for past mistakes.

Clarifying and understanding these choices is more urgent today than ever. Japan is at a crossroads, embroiled in a politics of nationalism that will have wide ramifications throughout Japanese society. Internationally, the parallel horizons of the three paths were jolted into collision by the new realities of the new millennium when military threats and belligerence throughout the Western Pacific increased with a multitude of events: the missile launches from China and North Korea, the Gulf War followed by wars in Afghanistan, Iraq and elsewhere in the Middle East, 9/11 and the “war against terror,” and territorial disputes involving Japan with China, Korea, and Russia. Japan’s drive for peace and reconciliation suffered serious setbacks in the shifting geopolitics, as the nation’s tilt toward re-militarization began. At the same time, a new politics of nationalism emerged domestically, fueled by the economic downturn and anxieties of globalization, and contested by stakeholders in disputes such as the treatment of war guilt and war criminals at commemorations (“the Yasukuni problem”), the mandate to use patriotic symbols (the national flag and anthem),4 inculcating patriotism in schools, and the treatment of Japan’s atrocities (“Nanjing massacre”) in textbooks and popular culture.5 This escalation in the politics of nationalism is testing the core of Japan’s postwar identity, and deepening the cleavage separating the nationalists, pacifists, and reconciliationists. In the following sections, I consider these three contending paths that are indelibly linked to the “history problem” in Japan’s political culture.

The Nationalist Path

The nationalist path subscribes to the notion that furthering the national interest is the best solution to overcoming the past. Thus the nationalist vision is to cultivate strong national belonging to move forward into the future. It emphasizes shared belonging and collective attachment to a historical community, and derives a social identity from that “traditional” heritage. People adopting this approach tend to use the language of national pride, and resent the loss of national prestige and international standing that came with defeat seven decades ago. They vary along a spectrum of intensity from aggressive hardliners to moderates in their search for respect, and vary from realist to idealist in seeking the competitive edge over other nations, like those in neighboring East Asia. Many proponents of this approach today are neonationalist public figures including politicians, intellectuals, and cultural critics.

From aggressive neo-nationalism to moderate civic and cultural nationalism, this approach partakes of a certain cultural resistance to cosmopolitanism.6 Recent Japanese prime ministers making official visits to the Yasukuni Shrine on commemoration day can be identified in this category, as well as those who passively condone traditional symbols of national honor like the national flag and the national anthem. Many of them favor revising the constitution, as Japan’s Prime Minister Abe Shinzō described in a new year’s interview with the Sankei newspaper in 2014. Asked about his vision for Japan in the year 2020, the year that Tokyo will again host the Summer Olympic Games, he responded:

“[I foresee that by 2020] the constitutional revision will be done.

At that stage, I want Japan to fully recover its prestige, and be recognized respectfully for its momentous contributions to world peace and stability in the region. Japan’s higher prestige will restore the balance of power in the Asia region.”7

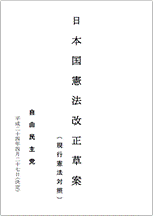

Emphasizing the recovery of prestige and respect, Abe makes clear that he wants to restore some fundamentals of nationhood that he believes were lost after defeat. His often-quoted ambition to “leave behind the postwar regime” (sengo rejiimu karano dakkyaku) is precisely about ending the long defeat, overcoming the cultural trauma of “a weaker Japan” that has been the subtext in postwar political culture, and gaining equal recognition in the world. In practical terms, this means strengthening Japan, and ending military disempowerment and Japan’s one-sided dependence as a “client state” of the United States. This nationalist vision is encapsulated in the draft revised constitution (kenpō kaisei sōan) announced in April 2012 by Abe’s political party (LDP): It is a nativized, domesticated version of the constitution, emphasizing tradition, patriotism, and duties to the state; and significantly, it changes Article 9, replacing the renunciation of possessing a military force with the establishment of a National Defense Army (kokubōgun).8

The nationalists’ impetus to inculcate national pride and patriotism in the country is readily explicable when we consider the erosion of support for traditionalist sentiments over many decades. Surveys show that national pride has declined in recent decades from 57% in 1983 to 39% in 2008, and it is consistently lower for the younger generations.9 Japanese high school students, for example, have a lower sense of national pride compared to American and Chinese counterparts.10 Japan’s younger generations born after the baby boom also report that they have no sense of attachment to the Emperor.11 The nationalists’ drive to cultivate patriotism in schools today actually emanates from a sense that their power base is eroding among the new generations who are disengaged and disinterested. In this sense, the mutual provocations that fan perceptions of threat in relations with China are effective tools to promote a stronger sense of national belonging and solidarity among these disengaged groups.

This approach to overcoming the past is also complicated. The accusation by the west that Japan is not doing enough to accept responsibility for World War II war crimes invites anger from nationalists who resent not being accepted as a member of the established western powers. Not being firmly established in the European order makes Japan’s path to shedding the stigma of defeat and asserting its established position more arduous than Germany’s. Taking account of this international stratification, the hurdle for recognition for non-western, non-white nations is doubly high and perpetually hard to clear.12 Nationalistic remembering is, then, not directed to reconciliation efforts but to gaining a position of moral and strategic superiority.13 In this sense, the attempt to achieve moral recovery from the long defeat takes the form of revising the script of defeat, questioning the legitimacy of the Tokyo Trial, the devaluing of the Yasukuni Shrine, and China’s victory in the Asia-Pacific War. From this vantage point, China is a country that exploits historical grievances to promote political gain. Relations with South and North Korea should also be “normalized,” that is, uncompromised by assumptions of Japan’s colonial and war guilt and uninhibited by constitutional constraints.

|

|

| The LDP proposal to revise the constitution emphasizes tradition, patriotism, and duties to the state (2012) | |

The pacifist creed has long been an important counterweight to nationalism in postwar Japan, and its proponents reaffirmed that mission in response to Japan’s dispatch of its Self-Defense Forces (SDF) to southern Iraq to take part in its first “humanitarian recovery mission” in support of the US. In June 2004, nine prominent Japanese public intellectuals gathered in Tokyo to announce the founding of the “Article 9 Association” (A9A, Kyūjō no kai) to protect the constitution from the state’s intensified efforts to revise it. The high profile cast ensured that the group would draw wide public attention. All of the founding members were of the wartime generation and had well-established credentials as postwar pacifists: Oda Makoto and Tsurumi Shunsuke had been leaders of the anti-Vietnam war movement; Ōe Kenzaburo, the Nobel laureate, is known for his pacifist conscience and outspoken public criticism of the state evoking comparisons with Germany’s Günter Grass; Miki Mutsuko had been active in the movement to attain redress for “comfort women” and joined the Asian Women’s Fund in 1995. Others included Katō Shūichi, a leading public intellectual and Okudaira Yasuhiro a prominent constitutional scholar. The Article 9 Association’s manifesto reads:The pacifist path subscribes to the notion that promoting healing and human security is the best solution to overcoming the past. Thus the pacifist vision emphasizes a radical anti-military ethos and anti-nuclear creed to make a fundamental break from Japan’s war history. This moral vision is a source of humanist pride as well as a collective identity that allows Japan to recover its moral prestige from the deviant past. As a people-centered vision, it focuses on all victims of war violence and nuclear threats and uses the language of human suffering and human insecurity wrought by military action. People adopting this approach vary along a spectrum of intensity from aggressive to moderate in their protest of military violence, and from national to international in their images of victims, including the victims of the atomic bombs and firebombings of the Asia-Pacific War and victims of current international wars such as Syrian refugees These proponents tend to be public leaders, from politicians to intellectuals and cultural critics who deeply mistrust the state as an agent for peaceful conflict resolution.

The Pacifist Path

The pacifist path subscribes to the notion that promoting healing and human security is the best solution to overcoming the past. Thus the pacifist vision emphasizes a radical anti-military ethos and anti-nuclear creed to make a fundamental break from Japan’s war history. This moral vision is a source of humanist pride as well as a collective identity that allows Japan to recover its moral prestige from the deviant past. As a people-centered vision, it focuses on all victims of war violence and nuclear threats, and uses the language of human suffering and human insecurity wrought by military action. People adopting this approach vary along a spectrum of intensity from aggressive to moderate in their protest of military violence, and from national to international in their images of victims, like those killed by atomic bombs and air raids and the refugees in Syria. These proponents tend to be public leaders, from politicians to intellectuals and cultural critics who deeply mistrust the state as an agent for peaceful conflict resolution.

The pacifist creed has long been an important counterweight to nationalism in postwar Japan, and its proponents delivered on that mission months after Japan dispatched the SDF to southern Iraq to take part in its first “humanitarian recovery mission.” In June 2004, a group of nine prominent Japanese public intellectuals gathered in Tokyo to announce the founding of the “Article 9 Association” (A9A, Kyūjō no kai) to protect the constitution from the state’s intensified efforts to revise it. The high profile cast ensured that the group would draw wide public attention. All of the founding members were of the wartime generation and had well-established credentials as postwar pacifists: Oda Makoto and Tsurumi Shunsuke had been leaders of the anti-Vietnam war movement; Ōe Kenzaburo, the Nobel laureate, is known for his pacifist conscience and outspoken public criticism of the state evoking comparisons with Germany’s Günter Grass. Miki Mutsuko had been active also in the movement to attain redress for “comfort women,” and joined the Asian Women’s Fund in 1995. Others included Kato Shūichi, a leading public intellectual and Okudaira Yasuhiro a prominent constitutional scholar. The Article 9 Association’s manifesto reads:

“Let our Constitution Article 9 shine upon this [changing] world, so we may hold hands with our fellow pacifist citizens around the world. For this purpose, we must re-select Japan’s constitution and Article 9 as sovereigns of this nation …. as it is our responsibility to shape the future of this country.

We appeal to the world to do everything possible to prevent the revision of this Constitution, and to protect it for future peace in Japan and the world.14

The popular response to this appeal was resounding: within a year and a half, more than 4,000 local citizens’ groups of the Article 9 Association sprang into action. Ten years later, there were more than 7,500 A9A groups of all imaginable constituencies throughout the country: A9A for film makers, poets, women, children, the disabled, patients, doctors, musicians, scientists, the fisheries business, trading companies, the mass media, Buddhists, Greens, the Communist Party, and so on, and local community groups that have sprouted by the thousands across towns, cities, and prefectures.15 An international petition drive ensued, organized by the Global Article 9 Campaign to Abolish War established by the youth movement Peace Boat (2005).

The accusation by the West that Japan is suffering from collective self-pity in its vow never to allow another war that would create more Hiroshimas and Nagasakis, misses the significance of pledging disarmament for a country with seven hundred years of military tradition and three victories in international wars. The pride in this radical break with the past is such that a citizen’s group nominated Article 9 for the Nobel Peace Prize in 2014.16

The popular appropriation of Article 9 as a form of civic identity was long in the making. Japan’s postwar pacifism, historian Akazawa Shirō explains, was born out of a profound skepticism for the state-defined “justice” that wrought massive sacrifices and immoral acts of violence.17 As war memory fostered persistent antipathy for the military and mistrust of the government’s ability to control the military, Article 9 came to function as an important constraint on the government that allayed those fears. What emerged over time was an anti-war pacifism based on a desire for human security, regret for a violent past, and a pledge to be model global citizens in the future. Peace is therefore a civic identity and a strategy of moral recovery, expressing contrition as well as an aspiration for an elevated moral status in the eyes of the world. This multifaceted discursive practice of peace is therefore fundamentally different from an anti-war pacifism based on questions of war responsibility.

The A9A was a corrective to defy the resurgence of aggressive nationalism in the 2000s; it reasserted the pride in a pacifist identity that had become a standard moral framework learned in schools18 and historically found role models in both Christian pacifists – like Nitobe Inazo, Yanaihara Tadao, and Uchimura Kanzo – and atheist pacifists – like Bertrand Russell and Albert Einstein who led the Pugwash movement dedicated to eliminating “all weapons of mass destruction (nuclear, chemical and biological) and of war as a social institution to settle international disputes.”19 However, only six months after the A9A was launched, the Japanese government announced the new National Defense Program Outline (NDPO) that broadened and realigned the range of Self Defense Force activities to react rapidly and multi-functionally to domestic and international emergencies. In this policy, China and North Korea were identified as “potential threats.”20

More recently, high-profile civic organizations and networks have sprung into action to defend the integrity of Article 9 and the constitution in response to the cabinet’s decision to reinterpret Article 9 to permit SDF to participate in international collective defense (2014). Those civic groups, consisting of scholars, public intellectuals, students, activists, and other public figures who are mostly of the postwar generation, vow to safeguard constitutionalism and constitutional democracy, and hold the government accountable to them. Organizations such as “Save Constitutional Democracy” represent this updated brand of pacifism that seeks a broader constituency to hold off further challenges to Article 9 by the nationalists in government.21 In this perspective, constitutional pacifism embraced by popular, democratic choice constitutes the ultimate moral recovery from the long defeat.22

|

The Founding of Article 9 Association (2004) |

The Reconciliationist Path

The reconciliationist path subscribes to the notion that enhancing transitional justice and moral responsibility in East Asia is the best solution to overcoming the past. This approach emphasizes rapprochement, an ethos of civil courage to face past wrongs, and prioritizes improved relations with Japan’s regional neighbors. To different degrees, people in this category recognize that accepting responsibility for past wrongs is indispensable to moving forward, and the only viable way for Japan to build mutual trust in the global world in general, and among the victims of Japanese wars throughout the Asia-Pacific in particular. They use a range of language from human rights and redress to friendship and pluralism, and emphasize the requirements of good relations with regional neighbors. Embraced by an eclectic mix of internationally-minded leaders in politics, business, scholars, grassroots networks, and civic activists, people vary along a spectrum from aggressive to moderate in their quest for redress and justice, and from realist to idealist in pursuing rapprochement. This approach is cosmopolitan, presupposing justice as a universal value, whether it comes from religious belief, feminism, socialism, transnational intellectual sensibilities, or declarations of international agencies.

This reconciliationist approach to overcoming the past prioritizes international dialogue to build relations with regional neighbors with antagonistic histories, based on mutual respect and, ultimately, mutual trust. Japan’s acknowledgement of its history of aggression is indispensable in this regard, together with an acceptance of responsibility and an effort to redress the wrongs. In the West German case, the effort to promote mutual understanding of the antagonistic histories with its neighbors started within years of the war’s end. Under UNESCO’s auspices, West Germany started an international dialogue first with France (1951), and then, with the advent of Ostpolitik, with Poland (1972). The joint textbook commissions carried out bilateral reconciliation work successfully by all accounts, and continue the efforts today with ongoing institutional support and state funding.23 By contrast, Japan’s joint history research projects with South Korea and China started only in the 1990s and 2000s, and with limited institutional and supranational resources compared to the German case. During this period of joint research Japan carried out both state and civil projects with South Korea and China.24 One such effort was a tri-national joint history textbook called History That Opens the Future published in 2005 by a group of 54 scholars, teachers, and citizens from Japan, China, and South Korea; it was the first textbook of its kind in East Asia published in all three languages.25 The preface reads:

“[This textbook] is about the history of East Asia in Japan, China, and South Korea.

East Asia’s history in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries is scarred by the wounds of invasion, war, and human oppression that cannot be washed away.

But … East Asia also has a long tradition of cultural exchange and friendship as many people work across national boundaries, committed to building a bright future.

We can build a brighter, peaceful future on this beautiful earth by inheriting the positive assets of the past, while thoroughly reflecting (tetteitekini hansei) on the mistakes as well.

How can we learn from the lessons of history to build a future that guarantees peace, democracy, and human rights in East Asia? Let’s think about it together….26

A joint history textbook project presumes that a shared historical perspective is possible based on some shared universal values such as peace building, democracy and human rights, as this preface describes. The effort calls for a search for a common language, and as much as possible, also a shared framework of understanding and interpretation. The common language behind History That Opens the Future is Japan’s history of imperial aggression and its damage to modern East Asia. The language of perpetration ties the three national histories together in what might be considered a primer on the origins of Japan’s “history problem.” Here the perpetrators are delineated clearly (Japan), as are the heroes who resisted the incursions (China and Korea), and the victims who suffered (China, Korea, and Japan). It also provides a blueprint for a possible resolution, which is that Japan must offer a full “apology and restitution (shazai and hoshō)” for its imperialism, invasions, and exploitation if East Asia is to find true healing, justice, and long-term reconciliation.27

Finding this common language is central in reconciliation work, yet hard to attain.28 Sociologist Gi-Wook Shin points to four key areas of reconciliation in East Asia – apology politics, joint history research, litigation, and regional exchanges – where the search for common ground is necessary for progress to be made.29 At a pragmatic level, it means that former adversaries, former perpetrators and victims must set aside the hate and prejudice that have stewed for decades, and find a reservoir of patience and good will. This process is also complicated ideologically by the “universal” international norm that defines a common language of justice in the global arena: human rights, democracy, and international norms such as crimes against peace (wars of aggression) and crimes against humanity (genocide, torture, persecution etc.)30 It was precisely the failure to find common ground in the understanding of “justice” that eventually ended the government- sponsored bilateral history research committees of the 2000s.31

Recent polls show that only a small fraction of Chinese and South Korean people (less than 11%) actually believe that Japan embraces pacifism or is committed to reconciliation, while much larger proportions (one-third to half of respondents) believe that Japan upholds militarism. At the same time, many in China and South Korea point to Japan’s “history problem” and the territorial disputes as obstacles that stand in the way of building better relationships.32

Indeed in the second phase of the trilateral scholars’ efforts to build international dialogue and mutual understanding in the 2010s, the political and social climate had grown considerably worse than in the 2000s. The follow up publication,33 which had set itself the ambitious task of providing an overarching regional history of East Asia, reflected this difficult climate. Finding common ground in the understanding of “justice” seemed strained, as evidenced by the failure to synthesize the section on collective memory that could have led to an understanding of the most pressing issue facing the three nations, the territorial disputes. Yet it is this type of painstaking and persistent work of cultivating civilian dialogue, however difficult it may be, that ultimately paves the way for future generations to pursue the task of East Asia’s reconciliation. These efforts join the assiduous work of many activist-scholars like Utsumi Aiko, Ōnuma Yasuaki, and others who have labored to achieve transitional justice and redress in Asia over the decades.34

|

History That Opens the Future (2005) |

The Broader Picture

The nationalist, pacifist, and reconciliationist paths have been vying for dominance over the past decades. They do not coalesce into a unifying national strategy for overcoming the past, and imply different strategies for political legitimacy and politics of social integration. The pacifist approach has been particularly strong in the areas of family memory and schooling, as I show in The Long Defeat. Mending the broken fences and healing the deep scars of history, however, will take more than the advocacy and practice of pacifism, however well-intentioned and well-practiced. Moral recovery in the current geopolitics is achievable only when respect can be gained from past adversaries and victims. The new tensions between Japan, China, and the Koreas make this task even more difficult.

Moving beyond the 71st anniversary of the end of war, former adversaries of the Asia-Pacific War now face crucial choices for the future of the East Asia region. The mounting tension centered on war memory politics today among Japan, China, and the Koreas is not only about righting past wrongs, but also about jockeying for position in the shifting geopolitics owing largely to the rise of China, and the continuing belligerence of North Korea as well as Japan’s own foreign policy under the Abe administration. Japan’s widely reported struggle today over remilitarization is fought precisely by these nationalists, pacifists and reconciliationists whose divergent understandings of Japan’s war and defeat parallel different interpretive narratives of the war and different views on contemporary Japanese international policies.

The divergent paths of nationalism, pacifism, and reconciliationism outlined in this essay explain the current battles over the nationalist government’s brazen push to revise the role of the Japanese military – elevating the Self Defense Force to a full military. Many of Japan’s current political problems – including its deteriorating geopolitical relations with China and the Koreas – continue to be fueled directly by the contentious meanings of defeat that remain unresolved.

This article is adapted from Chapter 5 of Akiko Hashimoto, The Long Defeat: Cultural Trauma, Memory, and Identity in Japan (Oxford University Press, 2015).

Notes

Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Rev. and extended ed. London: Verso, 1991.

Schivelbusch, Wolfgang. The Culture of Defeat: On National Trauma, Mourning, and Recovery. Translated by Jefferson Chase. New York: Metropolitan Books, 2003.

The Act on National Flag and Anthem 1999 (Kokki Oyobi Kokka ni Kansuru Hōritsu) mandated the use of the national anthem and flag in schools.

Fujioka, Nobukatsu, and Jiyūshugishikan Kenkyūkai. Kyōkashoga Oshienai Rekishi Tokyo: Fusōsha, 1996.

Sankei shinbun. “Gorin no toshi, nihon wa? Shushō: ‘Kaikenzumi desune’” 1.1.2014. Accessed 1/1/14.

Higuchi, Yōichi. Ima, ‘kenpō kaisei’ o dōkangaeruka: ‘Sengo nippon’ o ‘hoshu’ surukoto no imi. Tokyo: Iwanami shoten, 2013.

Kōno, Kei. “Gendai Nihon No Sedai: Sono Sekishutsu to Tokushutsu.” In Gendai Shakai to Media, Kazoku, Sedai, (ed) NHK Hōsō Bunka Kenkyujo, 14-38. Tokyo: Shinyōsha, 2008; NHK Hōsō Bunka Kenkyūjo, Gendai nihonjin no ishikikōzō, 7th edition. Tokyo: NHK Books, 2010.

Japan had the highest proportion of people who are not proud of their country (48.3%) compared to USA (37.1%) and China (20.3%). See Nihon Seishōnen kenkyūjo, Kōkōsei no gakushū ishiki to nichijō seikatsu: Nihon, amerika, chūgoku no 3 kakoku hikaku. Tokyo: Nihon Seishōnen Kenkyūjo. 2004, 8.

Kōno, “Gendai Nihon No Sedai”; Kōno, Kei, and Takahashi Kōichi. “Nihonjin No Ishiki Henka No 35nen No Kiseki (1): Dai 8 Kai ‘Nihonjin No Ishiki 2008’ Chōsa Kara.” Hōsō Kenkyū to Chōsa April (2009): 2-39. Kōno, Kei, Takahashi Kōichi, and Hara Miwako. “Nihonjin No Ishiki Henka No 35nen No Kiseki (2): Dai 8 Kai ‘Nihonjin No Ishiki 2008’ Chōsa Kara.” Hōsō Kenkyū to Chōsa May (2009): 2-23.

Zarakol, Ayse. After defeat: How the East learned to live with the West, New York: Cambridge University Press 2011. 198, 243, 253.

Kosuge, Nobuko. Sengo wakai: Nihon wa

Alexis Dudden “The Nomination of Article 9 of Japan’s Constitution for a Nobel Peace Prize” Japan Focus Apr. 20, 2014.

Akazawa, Shiro. Yasukuni jinja: Semegiau ‘senbotsusa tsuitō’ no yukue. Tokyo: Iwanami shoten. 2005, 7, 257-60

Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs. Principles, Structure and Activities of Pugwash For the Eleventh Quinquennium (2007-2012).

“Scholars form ‘Save Constitutional Democracy’ to challenge Abe’s ‘omnipotence’” Asahi shinbun Asia & Japan Watch. April 18, 2014.

Okuhira, Yasuhiro, and Jiro Yamaguchi. eds. Shūdanteki jieiken no naniga mondaika: Kaishaku kaiken hihan. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 2014.

Alexandra Sakaki. Japan and Germany as Regional Actors: Evaluating Change and Continuity After the Cold War. Florence, KY: Routledge 2012; Kondo, Takahiro. Kokusai Rekishi kyōkasho taiwa: Yōroppa ni okeru “kako” no saihen. Tokyo: Chūōkōronsha, 1998; Schissler, Hanna, and Yasemin Soysal, eds. The Nation, Europe, and the World : Textbooks and Curricula in Transition. New York: Berghahn Books, 2005.

Yang, Daqing, and Ju-Back Sin. “Striving for Common History Textbooks in Northeast Asia (China, South Korea and Japan): Between Ideal and Reality.” In History Education and Post-Conflict Reconciliation : Reconsidering Joint Textbook Projects, edited by K. V. Korostelina, Simone Lässig and Stefan Ihrig, 209- 30. New York: Routledge, 2013.

Nitchū-Kan 3-goku Kyōtsū Rekishi Kyōzai Iinkai. Mirai o hiraku rekishi: Higashi ajia 3-goku no kingendaishi [History That Opens the Future] Tokyo: Kōbunken, 2005.

Kasahara Tokushi. “Shimin karano higashiajia rekishikyōkasho taiwa no jissen: Nit’chūkan sankoku ni okeru ‘Mirai o hiraku rekishi’ to ‘Atarashii higashiajia kingendaishi’ no hakkō,” Sekai 2013 March No. 840, 45-55; Kim, Seongbo. “Higashiajia no rekishi ninshiki kyōyū e no dai ippo.” Sekai 2006 October, 225-234.

Shin, Gi-Wook. “Historical Reconciliation in Northeast Asia: Past Efforts, Future Steps, and the U.S. Role.” In Confronting Memories of World War II: European and Asian Legacies, edited by Daniel Chirot, Gi-Wook Shin and Daniel C. Sneider, 2014, 157-85.

Park, Soon-Won. “A History That Opens the Future: The First Common China-Japan-Korean History Teaching Guide.” In History Textbooks and the Wars in Asia: Divided Memories, edited by Gi-Wook Shin and Daniel C. Sneider, 230-45. New York: Routledge, 2011; Sneider, Daniel C. “The War over Words: History Textbooks and International Relations in Northeast Asia” in History Textbooks and the Wars in Asia, 246-68.

The reports of the official Japan-ROK South Korea Joint History Research Committee (2002-05 and 2007-10) are available here and here.

The reports of the Japan-China Joint History Research Committee (2006-09) are available here.

For an assessment of how textbooks contents differ on controversial events, see Yoshida, Takashi. 2006. The making of the “Rape of Nanking”: History and Memory in Japan, China, and the United States. New York: Oxford University Press.

Genron NPO. “Dai 2 kai nikkan kyōdō yoron chōsa.” 2014; 2014. “Dai 10 kai nitchū kyōdō yoron chōsa kekka”.

Those who thought of Japan as a pacifist society were 10.5% in China and 5.3% in South Korea; those who thought of Japan as a reconciliationist society were 6.7% in China and 3.9% in South Korea. Those who believed that Japan espoused militarism today were 36.5% in China and 53.1% in South Korea. In China, respondents believed that the “history problem” (31.9%) and the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands (64.8%) were major obstacles for developing a good relationship; in South Korea, the respondents ranked Takeshima/ Dokdo Island (92.2%) and the “history problem” (52.2%) highly as major obstacles for building friendships.

Nitchūkan 3-goku Kyōtsū Rekishi Hensan Iinkai. Atarashii higashiajia no kingendaishi (jō): Kokusaikankei no hendō de yomu: Mirai o hiraku rekishi Vol. 1. Tokyo: Nihon hyōronsha, 2012. Atarashii higashiajia no kingendaishi (ge): Tēma de yomu hito to kōryū: Mirai o hiraku rekishi Vol. 2. Tokyo: Nihon hyōronsha, 2012.

Utsumi, Aiko, Yasuaki Onuma, Hiroshi Tanaka, and Yoko Kato. Sengo sekinin: Ajia no manazashi ni kotaete. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 2014.