Abstract

This article investigates the history and contemporary development of the local anti-nuclear experience in Gongliao district, Taiwan. It traces villagers’ intricate relations with political parties, their frustration with the decision making process, and efforts to sustain local anti-nuclear momentum at a time when the anti-nuclear movement was in decline. By exploring local villagers’ three decades of anti-nuclear efforts, this article focuses on their change of tactics, networks and ideologies, and explains how these changes had happened. It argues that local anti-nuclear activists played an important role in transforming an anti-nuclear movement from a party-led activity to an issue-based protest independent of party control. The transformation was facilitated by the deepening of a place-based consciousness among local activists.

Key Words

Anti-nuclear Movement, Informal Life Politics, Locality, Grassroots Activism, Taiwan, Gongliao

Introduction

The Chinese lunar New Year was still months away, but the residents of Gongliao district, who for years had fought plans to construct a fourth nuclear power plant in their neighbourhood, were in a festive mood. On 27 October 2000, the Minister of the Executive Yuan announced that the newly-elected government led by the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) would suspend construction of the plant. Villagers popped bottles of champagne and set off fireworks to celebrate the historical moment. The leader of the locally organized Yanliao Anti-nuclear Self-help Association, ChenChing-tang, wept for joy at the news. Unable to find words to express his gratitude, village head Chao Kuo-tong promised to erect copper statues of the DPP top leaders next to the gods and goddesses inside the local Mazu temple to commemorate their “moral politics.”1 However, no one would expect that this very joyful moment was to be the tipping point of the anti-nuclear movement in Taiwan and the local anti-nuclear villagers’ relationship with the DPP. As it transformed from an opposition to a ruling party, the DPP increasingly focused on political stability rather than reform. Despite its pro-environmental profile before the election, it began to dilute its former commitment to environmental protection to make overtures to the business community. Facing pressure from its political competitor-the Kuomintang (the Nationalist Party, KMT)-and from domestic and international corporations, the party soon abandoned plans to cease construction of the nuclear power plant. The reversal subjected the anti-nuclear movement to a precipitous decline.2 The promised copper statues were never erected; joyful tears of activists turned to distrust and grievances. How did the Gongliao villagers embark on this anti-nuclear journey? What was their relationship with party politics and how did they recover from disillusion with the DPP leadership in the anti-nuclear movement?

The anti-nuclear movement constitutes an important social movement in the history of democratisation of Taiwan. Its ongoing development continues to influence power dimensions in Taiwan’s contemporary politics. Yet most of the literature has examined the movement from the perspective of the state and institutional change. Local activists’ anti-nuclear journey only receives scholarly attention when it enters the realm of formal political practices, such as election campaigns and parliamentary debates.3 The long-term daily struggle in local areas, which was difficult to mould into smooth and continuous narratives of a social movement, remains neglected and scantily documented. Indeed, the anti-nuclear pursuits visible in formal political arenas are only the tip of the iceberg of the movement. Political demands, tensions, practices, as well as mobilisational and policy strategies spread widely and invisibly through the social fabric at the local level before merging into visible street protests.4 Politics, as Tessa Morris-Suzuki argues, is a transformative process. The efforts of grassroots communities to organize themselves in response to challenges to their livelihood, which she termed “informal life politics,” deserve careful consideration. They not only reveal but also influence the changing forms of political power.5 Robert Weller also emphasized the importance of local communal ties beyond formally organized institutions in shaping political developments in Taiwan.6 Without knowledge of local experience, it is hard to understand how anti-nuclear movements in Taiwan developed from a party-led movement to an independent one; and how communities were reconstructed when partisan politics created divisions among neighbours.

This article investigates the history and contemporary development of the local anti-nuclear experience. It traces local villagers’ intricate relations with political parties, their frustration with the decision-making process, and efforts to sustain local anti-nuclear momentum at a time when the national anti-nuclear movement was in decline. By exploring local villagers’ three decades of anti-nuclear efforts, it focuses on their change of tactics, networks and ideologies and explains how these changes occurred. This approach is inspired by McAdam, Tarrow and Tilly’s call to consider social movements as dynamic processes rather than static opportunity structures.7 It also attempts to consider the element of culture and emotions in the studies of social movements, which have conventionally focused on political resources and opportunities. It argues that local anti-nuclear activists played an important role in transforming anti-nuclear movements from a party-led activity to an issue-based protest free of party domination. The transformation was facilitated by a deepening of the place-based consciousness of local activists. Before 2000, villagers perceived Taipei as the centre of the anti-nuclear movement and Gongliao as a subordinate locale to provide political support. After 2000, villagers started to consider the local space as the primary location to pursue anti-nuclear activism. The transition involved attempts to integrate local memories and feelings into the national anti-nuclear discourse. Such a change was a result of locals’ frustration with partisan politics. The deep engagement of external groups with the local community also encouraged locals to seek an alternative route to politics.

Scholars have examined the notion of place in the agenda of social change. The challenge lies in drawing the boundary when bringing local space into discussion: whether the place is viewed as an “open and porous” space that derives meaning and representation from the nation and the global world,8 or a distinctive entity free from marginalisation imposed from the outside. This article shows how, under certain circumstances, villagers’ sense of locality may be transformative. Gongliao villagers, through a painful process, gradually acquired what Arif Dirlik called a sense of “groundedness” of the locality. This approach emphasizes the “fixity of places and the limitations set on the production of place by its immediate environment.”9 It accentuates ecological aspects of place and calls attention to “what is to be included in the place from within the place,” particularly control over the conduct and organisation of everyday life. Such an understanding transformed the tactics of protest with deep implications for Taiwan politics.

Grassroots Anti-Nuclear Activists’ Route to Partisan Politics

Gongliao district is located in the east corner of Taiwan around 40 kilometres from Taipei city. In 1984 local fishermen and farmers learned that the state-owned Taiwan Power Company (Taipower) would build a fourth nuclear power plant (4NPP) north of the local Fulong beach. Nuclear power was no longer a new source of energy for Taiwan. The first two nuclear power plants had been built close to the northeastern tip of Taiwan (Shimen District and Wanli township) in the late 1970s, and a third one on the southwest coast (Hengchun township) in the early 1980s. Completed in the period when people were not yet aware of the implications of nuclear power, none of them had stirred social protests.

Back in the early 1980s, the Gongliao villagers had little knowledge of the potential danger of nuclear power. They were more concerned with the government’s unfair expropriation of their land and property for the power plant’s construction.10 Learning from the local fishery union that the price of fish had dropped sharply in the vicinity of other nuclear power plants, fishermen near Gongliao worried that the same fate would befall them.11 Concerns for their local economy motivated villagers to appeal to the government to reconsider the nuclear power project. The high risk under the Kuomintang’s authoritarian rule deterred local villagers from reaching out for political support. Protests were organized in an ad hoc manner without long-term guidelines.

Meanwhile, the tangwai was vocal in challenging the KMT’s nuclear power policy. The tangwai (literally “outside the party”) was a general term for the political opposition before the formation of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in 1986. In the 1980s, environmental pollution became a key focus of the group. Utilizing progressive publications such as Life and Environment and New Trend, the tangwai addressed a large number of environment-related issues that had been largely censored in KMT-controlled newspapers. They believed that environmental problems, which involved the relations among nature, individuals, business, and the state, were political issues, and that the end of the KMT dictatorship was essential to reduce Taiwan’s environmental hazard.12 Despite the tangwai group’s efforts to incorporate villagers in their political pursuit, it failed to attract grassroots protesters. Before the lifting of martial law, any cooperation with the opposition would easily incur government suppression. The local villagers were not ready to challenge the rule of the KMT as the tangwai hoped. Yet silence did not suggest consent to the state’s nuclear power policy. Anxiety over nuclear risks was aggravating, particularly due to academics’ efforts to spread nuclear knowledge among the local villagers.

Having been trained in science in the West, particularly in the United States, academics and intellectuals were privy to information on radiation leakage such as the Three Mile Island Incident of 1979. Their knowledge about nuclear hazards directly challenged Taipower’s promise of nuclear security. But debates about the validity of nuclear power were mostly held among small groups of engineers and bureaucrats, instead of trickling down to the local level to strengthen the Gongliao villagers’ appeal.13 The political hurdles that lay between local villagers and academics began to disappear after the abolition of martial law in 1987. No longer satisfied with the “gentlemen’s disagreements” among urban-based scientists, scholars started to travel to Gongliao and educate villagers about the risk of nuclear energy. They explained the scientific evidence in plain language and communicated with them in local dialect. Their localized strategy was effective in winning villagers’ trust.14

Compared to the Tangwai group/DPP, intellectuals were much more receptive to local villagers. They enjoyed high reputation among locals who embraced the tradition of respecting scholars and intellectuals. The knowledge they brought to the local area constituted the source of power and authority that villagers could rely on to strengthen their anti-nuclear case. Meanwhile, warnings on the risk of nuclear technology were not foreign to local ears. Elder generations educated during Japanese colonial rule (1895-1945) had access to Japanese materials on the tragedy after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Scholars’ messages simply enhanced the existing indigenous concerns that the 4NPP not only threatened the local economy but villagers’ health and life. The Chernobyl nuclear power accident in 1986 further enhanced villagers’ fears of a nuclear disaster.15 Although villagers at first did not dare to openly attend the lectures, rather “overhearing” scholars’ speeches from a distance, information about the hazard of nuclear power still quickly spread across Gongliao.16

|

Public seminar on the use of electricity in Gongliao, March 1988, by Liao Ming-hsiung, collected by Wu Wen-tung |

Villagers eventually confronted the government’s nuclear policy by establishing the Yanliao Anti-nuclear Self-help Association (YASA) in March 1988. According to local anti-nuclear activists, the decision to act was prompted by a sham policy seminar organised by Taipower. With the endorsement of local officials, on 1 March 1988 Taipower staff came to Aodi primary school to inform residents about nuclear power. Concerned villagers went to the seminar only to discover that it was no more than a lottery for attendants. Prizes included large electronic appliances, such as televisions and refrigerators. Taipower’s “generosity” attracted many attendees. Yet issues such as safety, impacts on marine life, and land expropriation remained unaddressed. The second day, news spread in the national media that Gongliao villagers had warmly welcomed Taipower’s plans to construct a nuclear power plant in their neighbourhood. Irritated by Taipower’s deception and contempt for local feelings, villagers decided to mobilize.17 Five days later, YASA was established. 1500 villagers attended the establishment conference.18 Villagers intended to send a clear message to the state that locals were prepared to organize to resist the state’s nuclear policy.

Informal and communal ties played an important role in mobilizing the locals, particularly those revolving around the temple. As centres of local identity, temples often served as political bases for the local community. They offered the local movement powerful moral support, and often provided key financial resources if they could be won over.19 Before the establishment of YASA, Wu Tien-fu, a staff member of the Renhe temple (a Mazu temple) had sought divination from the local goddess Mazu, and received the message that “the fourth nuclear power plant would be built, but not operate.”20 Although villagers puzzled over what this really meant, the message from Mazu constituted a moral sanction from the god. This greatly boosted local confidence. On 12 March, YASA organized its first public protest: collecting Taipower’s gift calendars from villagers they put them in flames in front of the local Mazu Temple.

The event was remembered as their “declaration of war” against the state’s nuclear power policy.21

|

YASA collecting Taipower calendars, March 1988, by Liao Ming-hsiung, collected by Wu Wen-tung |

YASA kept a rather flat organization structure. Apart from a head and two sub-heads elected by its members, the association had no intermediate layer between the bottom and the top. The leaders of the association served the community on a voluntary basis, receiving no salary from the group. To prevent domination by a single leader, YASA members elected their head every year and no head was allowed to lead for more than two years. To be qualified as a YASA leader, one should not hold any government position. This was to maintain the association’s autonomy from the state.22 Yet taking a leadership position in YASA meant assuming political responsibilities and risks. “It was a very tiring job,” Lin Fu-lai recalled, “even my family phone was tapped during the time I was the head.”23 Wu Wen-tung also told me that the police regularly checked his household registration book (hukou) three times a day as a political harassment when he led the local anti-nuclear protest.24

Before an activity, local liaisons would visit each household to invite villagers in person. “Human contact” was emphasized as a way of showing respect as well as strengthening the bond of the community.25 The association was financially supported by membership fees and local fund-raising. Most funding came from local donations collected at the annual Mazu temple fair on 16 March in the lunar calendar.26 As former YASA leaders recalled, YASA usually collected about four hundred thousand New Taiwanese dollars in the temple fair every year, sufficient to cover YASA’s expenses for a year.27 To make the budget transparent to the public, YASA usually provided a full record of its annual spending in its newsletters.28 The flat and transparent management posed a sharp contrast to the hierarchical and opaque bureaucracy of the government. It also increased YASA’s credibility and reputation, which were key to attracting popular support.

The anti-nuclear campaign changed the local political landscape. For decades, local politics in Taiwan were notable for factionalism. The lack of local connections after the KMT retreated to Taiwan led the party to co-opt local elites via patron-client networks. The party usually cultivated relations with several factions at the same time and tried to maximize political benefits by striking a balance through their contention.29 Before the late 1980s, local politics in Gongliao were dominated by the Old Faction (Jiupai) and the New Faction (Xinpai).30 When YASA was established, Gongliao township was governed by a New faction member Wu Ching-tung, who tended to follow the central government’s position on nuclear power. This deterred other New Faction members from joining YASA, creating the potential for the Old Faction to dominate the association.31 Yet involvement by the New Faction was crucial, not only because of the necessity to rid YASA of factional divisions, but also because their participation could help ease tensions with local officials and provide links to resources under their control, such as the fishery union and temple management committee.32 As a result of these pragmatic concerns, Lien Ta-ching, a New Faction member, was appointed as YASA’s first head. To balance Lien’s influence, ChenChing-tang, an Old Faction member, was installed as one of its sub-heads.33 Although the division between the Old and New factions lingered for a while, members of both factions started to join YASA, as the anti-nuclear movement grew stronger.34 This eventually dissolved the boundary between the two factions and united the community behind the common anti-nuclear cause.

However, not long after YASA had freed itself of factionalism, it became involved in a larger partisan struggle between KMT and DPP. With anti-nuclear intellectuals as the broker, local activists started to form an alliance with the DPP. In 1989, YASA joined the Taiwan Environmental Protection Union (TEPU) as its northeastern branch. Led by a group of anti-nuclear academics, TEPU worked as an umbrella organisation to coordinate environment-related movements throughout the island.35 It not only connected YASA to a nation-wide community of environmentalists, but led YASA on the track of partisan politics. Many of local leaders were DPP politicians whose protests were supported by the party. In 1989 alone, fourteen members of TEPU joined elections for legislators and city councillors, all of them being DPP politicians.36 Lin Chun-yi, one of the TEPU pioneering anti-nuclear scholars, for example, joined the DPP in 1989.37 Later, he famously proclaimed that “anti-nuclear is anti-dictatorship,” thereby linking the nuclear issue with the DPP’s political goal of challenging KMT authoritarian rule.

Influenced by scholars, YASA leaders gravitated to the DPP’s leadership, many switching their political identity. Before 1994, the head of YASA was either a KMT member or a non-party independent. Although affiliation with the KMT was often a pragmatic measure to gain benefits within the system rather than an indication of political loyalty, YASA leaders were still keen to sever this affiliation so as to maintain their political integrity. The founding leader of YASA, ChenChing-tang, moved from the KMT to the DPP in the mid-1990s. Wu Wen-tung, who had led YASA as a non-party member in 1994, also joined the DPP in the late 1990s. Since 1995, YASA has been led exclusively by DPP members. (See Table 1) The change of party affiliation was a declaration of their criticism of KMT environmental policy and their belief in the DPP’s promise of change.

Table 1: Party affiliation of the head of YASA38

|

Number |

Name |

Tenure |

Party Affiliation |

|

1 |

Lien Ta-ching |

1988-1989 |

Nil (New Faction) |

|

2 |

Lien Ta-ching |

1989-1990 |

Nil (New Faction) |

|

3 |

Chiang Chun-he |

1990-1991 |

KMT |

|

4 |

Chiang Chun-he |

1991-1992 |

KMT |

|

5 |

Chen Ching-tang |

1992-1993 |

KMT |

|

6 |

Chen Ching-tang |

1993-1994 |

KMT |

|

7 |

Wu Wen-tung |

1994-1995 |

Nil |

|

8 |

Lin Fu-lai |

1995-1996 |

DPP |

|

9 |

Chao Jui-chang |

1996-1997 |

DPP |

|

10 |

Chao Jui-chang |

1997-1998 |

DPP |

|

11 |

Chen Ching-tang |

1998-1999 |

DPP |

|

12 |

Chen Ching-tang |

1999-2000 |

DPP |

|

13 |

Chen Ching-tang |

2000-2001 |

DPP |

|

14 |

Chen Ching-tang |

2001-2002 |

DPP |

|

15 16 |

Wu Wen-tung Wu Wen-chang |

2002-2010 2011- |

DPP Nil |

Local anti-nuclear resources were quickly absorbed by the DPP to become a main source of support for its local election campaigns. Under the DPP’s leadership, the anti-nuclear protests transformed into anti-dictatorship and anti-corruption campaigns, aimed directly at the KMT. With the slogan “vote out pro-nuclear politicians,” Gongliao villagers supported Yu Ching, a veteran of the anti-nuclear activists, to become the head of New Taipei County. As a DPP member, Yu’s inauguration ended decades of KMT monopoly of the county and compounded the division between central and local governments with respect to nuclear policy. He resisted the KMT government’s nuclear plan by refusing to issue construction permits. Branding the nuclear power plant “illegal,” he called on Taipower to remove unauthorised buildings in Gongliao.39 To strengthen his anti-nuclear position, he supported activists who organized a local referendum in 1994 in Gongliao. Among the 58% turnout, 96% voted against construction of the power plant. Although Taipei declared the referendum lacking legal validity, Yu’s persistent anti-nuclear gesture greatly boosted the morale of local grassroots activists. It reaffirmed the idea that the DPP was a reliable party that would lead the anti-nuclear movement at the grassroots to challenge the KMT’s pro-nuclear policy. As Chen Shi-nan commented, allying with the DPP back then was a rational choice for local grassroots activists:

We need a national party to have our voice heard. The issue of nuclear power will only be noticed by people outside the village through parliamentary debate between political parties. Otherwise who will pay attention to the view of Gongliao villagers, who are considered an uneducated violent mob?40

However, the grassroots movement did not always benefit from alliance with the DPP. In 1991, with tacit approval of local county leaders of the DPP, Gongliao villagers built barricades at the designated construction site to combat the KMT government’s persistent efforts to construct the fourth nuclear power plant. On October 13, when police officers tried to dismantle the barricades, peaceful protests turned into violent confrontation, leading to the death of a police officer. The tragedy swayed public opinion. What used to be seen as a “green and peaceful” environmental movement, turned into “anti-nuclear violence.”41 Both the KMT and the DPP refused to take responsibility for the tragic consequence, leaving the grassroots to bear the brunt of public criticism.42 The accident, which became known as the 1003 event, dealt a heavy blow to the morale of local anti-nuclear activists. For a while, the Gongliao villagers were under close surveillance. Anti-nuclear villagers were interrogated by the police, while key leaders of YASA were thrown into jail. Gongliao people were thereafter known as a “violent mob,” a label that cast a shadow over the locals for more than a decade.

Meanwhile, YASA leaders also realized that supporting DPP candidates in elections often divided grassroots anti-nuclear activists. As Wu Wen-tung complained:

If the candidate we supported won an election, it was a loss for us. The elected one usually prioritized the party line over the anti-nuclear cause after joining the government. If our candidate lost the election, however, we lost even more, since he would blame us for not helping enough.43

Indeed, various political tensions between local and central political groups were concealed under the umbrella of the anti-nuclear cause. While local grassroots activists considered anti-nuclear power the goal of their protests, politicians regarded the protests as a means to ascend the political ladder.

The DPP evinced less interest in the anti-nuclear cause in the mid-1990s. In 1996, the DPP and the New Party proposed to re-consider the bill ending the construction of the 4NPP. With little chance to win, the DPP made a secret deal with the KMT to trade their votes for other political concessions. The deal was leaked to the grassroots anti-nuclear activists who rallied outside of the Legislative Yuan and divided the anti-nuclear camp.44 Some criticized DPP members as “collaborators under the guise of the anti-nuclear cause.”45 Others continued to support the party but blamed the KMT for political manipulation. Sensing that grassroots activism could become uncontrollable, DPP leaders readjusted relations with the grassroots after the assembly. Instead of perceiving cooperation with the grassroots movement as equally important as parliamentary elections, they recalibrated their strategy to make the former subordinate to the latter.46

Despite complications within the alliance between the local grassroots and the DPP, the two remained bound together in the anti-nuclear cause. Anti-nuclear protests had intertwined with the DPP’s party politics and become an integral part of the party’s struggle for ascendance. The party provided grassroots protesters with political access, while the grassroots movements guaranteed votes for the DPP in elections. For them, it was more a matter of replacing pro-nuclear officials with DPP members. As a villager claimed, “when the village leader, the township leader, the mayor and the president are all our men [DPP members], we shall see the realization of our anti-nuclear cause.”47

Also, villagers genuinely perceived the solution lay in the streets of Taipei-beyond the local area. Organizing local villagers to travel to Taipei to participate in protests and public campaigns became YASA’s main tasks in the 1990s. YASA leaders were unconsciously following the hegemonic consensus that Taipei was the centre of the anti-nuclear movement. Gongliao thus remained a marginal area beyond the concern of most urban-based elites and politicians. The physical environment of the locality as well as the immediate social experiences only became valuable when it merged with the political discourses in the centre.

“Betrayal” of the DPP

The year 2000 presented a great opportunity for the anti-nuclear movement to achieve a meaningful result. In March, Chen Shui-bian, the leader of DPP, won the highly competitive presidential elections. His victory ended over fifty years of Kuomintang rule, a party which had taken over Taiwan following the defeat of Japan in the Pacific War and established its headquarters on the island after losing the mainland the Chinese Communist Party in the civil war (1946–1949). Despite the KMT’s achievements in fostering economic growth in Taiwan, people were restive under the party’s authoritarian rule as well as its cronyism with business tycoons, local factions and organized gangsters. The electoral loss of the KMT signalled a popular desire for progressive social reform.48

Chen’s victory of Chen greatly boosted the morale of anti-nuclear activists. They organized an anti-nuclear demonstration right before Chen’s inauguration to urge him to deliver on his anti-nuclear promise.49 Upon inauguration, Chen referred the case of the nuclear plant to the Ministry of Economic Affairs for review. The process was cut short after ChangChun-hsiung, the newly appointed Minister of the Executive Yuan, announced the end of the fourth nuclear power plant project. After more than a decade of support for the DPP, locals finally saw the construction of 4NPP halted.

However, Chang’s announcement prompted severe protest from the Legislative Yuan (parliament) dominated by the KMT. In the absence of a consensus between the Executive and the Legislative Yuan, the case was sent to the Council of Grand Justices (Taiwan’s Supreme Court) for review. Refraining from making a judgment on nuclear policy, the council concluded that Chang’s order lacked due process, have failed to seek prior approval from the Legislative Yuan. Chang submitted the bill to the Legislative Yuan only to have it vetoed. After a pause of just one hundred days, construction of the fourth nuclear power plant was reactivated.

Gongliao villagers were devastated by these changes, frequently referring to DPP politicians as “liars” and “betrayers.”50 Chao Jui-chang, a local anti-nuclear leader, experienced being sandwiched between the DPP leaders and local villagers.51 Unable to find a channel to release their frustration, villagers vented their emotions against local anti-nuclear leaders. The former head of YASA, ChenChing-tang, a frail old man, received repeated telephone calls and visitors to his home, chastising the DPP’s unpredictable policy and complaining about local leaders’ cooperation with them.52 Yet Chen himself was struggling to recover from the DPP’s change of policy. Scandals which exposed attempts by DPP leaders to secure personal profits by making arrangements between Taipower and subcontractors further tarnished the party’s reputation.

The former anti-nuclear alliance linking local grassroots organization, the DPP and external scholars started to dissolve. After the transfer of power, some prestigious environmentalist scholars were integrated into the DPP government as leaders of the Environmental Protection Administration. A cabinet-level Nuclear Free Homeland Communication Committee was also established to raise public awareness of nuclear risk. The increased scope and depth of institutional participation reduced the incentive to seek anti-nuclear solutions through social movements. Meanwhile, the scholar-led TEPU was more lenient toward the DPP than Gongliao villagers. Most of TEPU’s leaders attributed the DPP’s change of nuclear policy to the non-cooperation of KMT legislators. Few questioned the sincerity of the party’s anti-nuclear stance. They believed that given the situation, the DPP had done all it could, and that cooperation with the party was the most effective way to advance their anti-nuclear goals.53 This view was not shared by Gongliao people. Disheartened by the failure of the DPP to deliver on halting the project, villagers expressed little interest in participating in anti-nuclear demonstrations organized by TEPU.54

Anti-nuclear movements declined after 2001. While in 2000, the United Evening News and the United Daily carried 667 articles about anti-nuclear issues, the number dropped to 458 in 2001 and plummeted to 149 in 2002. The paper’s coverage of anti-nuclear topics continued to decline from 2004 to 2010, with only some 40 articles about nuclear issues each year. (See Table II)

Table II: United News’ reports on “anti-nuclear” issues, 2000–2010

|

Year |

2000 |

2001 |

2002 |

2003 |

2004 |

2005 |

2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

|

Number of reports |

814 |

525 |

160 |

153 |

58 |

73 |

78 |

44 |

33 |

53 |

32 |

Source: collected by author based on the United News’ database, searched by keyword “fanhe“

Indeed, nuclear protests had become a cliché that failed to attract the public. Fewer people continued to participate in programs organized by YASA. Due to the small number of members, the annual assembly of the association had to be cancelled in 2002. As a villager recollected, Gongliao was overwhelmed by a sense of despair. “Even Chen Shui-bian was unable to stop the nuclear project as a president; what hope do we have?” “Those [DPP members] who chanted anti-nuclear slogans the loudest then, reap the most political benefits now.” “DPP politicians are just like their KMT counterparts. They only care about their political interests, not our anti-nuclear cause.”55 Villagers avoided talking about anti-nuclear issues, as if forgetting was a way of healing.

Suspicions about the local protesters began to grow among the public. Some regarded the local protests as another “not in my backyard” movement that prioritized local over national interests. Others suspected that the local Gongliao people were simply intent on reaping government subsidies through their protests, although they had already enjoyed the best welfare compensation anywhere in Taiwan: free primary school education, free school lunches, a handsome premium of accident insurance for every villager, free 200 kw supply of electricity for each household, and various scholarships for local students to attend college.56

Indeed, government subsidies to the villagers weakened the moral foundations of the local grassroots movement and divided local anti-nuclear activists. Many villagers withdrew from the anti-nuclear front after receiving the social benefits. A few of the most radical activists refused Taipower’s favours, insisting that gifts eroded local anti-nuclear morale.57 The subsidy deepened distrust between anti-nuclear activists and local authorities. As a YASA petition letter to the DPP chairman recorded, officials of Gongliao County and the local fishery union were ready to suppress radical anti-nuclear activists on grounds that they disrupted social peace.

“For local officials, anti-nuclear was a measure to squeeze personal benefits from Taipower…. Fighting for a decade under KMT rule, we had never been labelled “environmental hooligans” as today. How pathetic! How pathetic! “58

Children of the more radical activists were reported to be isolated by their classmates in school.59 As Taipower increased recruitment from the local area, some veteran anti-nuclear leaders were also blamed for hypocrisy when it was found that their relatives had accepted jobs with the company. The anti-nuclear cause that had once united the local community, now divided it. Yet the divide was not surprising to locals, since it only made visible previously hidden tensions within the anti-nuclear cause. The result was misunderstanding among the general public of the fact that local people opposed the nuclear power plant. Nevertheless, it was outside social activists who were prepared to instigate conflict in society and pushed the anti-nuclear line hardest.60

The aging of the protest leaders also plagued local anti-nuclear movements pursued in the course of a generation. Although a decades-long social phenomenon ought not to be reduced to biological generations, it is undeniable that the rhythm of birth and death and the change of physical interactions affects the trajectory of a social movement.61 For a while, the key task of YASA was to help organize funerals of former leaders.62 While veteran activists were aging, the village was losing young generations to the metropolis. How to recover from the downturn of anti-nuclear movements? How to attract support from the general public, and young people in particular, for a cause that had become a political cliché?

Recovery from “Betrayal”

The decline of the anti-nuclear movement nevertheless provided an opportunity for grassroots activists faithful to the anti-nuclear cause to regain leadership and autonomy in the movement. As the movement lost its political advantage after 2001, local and central interest groups that used to take advantage of the movement for other political benefits quickly withdrew their resources and support. Although this dealt a heavy blow to YASA, it also enabled “pure” anti-nuclear activists who deeply cared about the locality to resume YASA leadership.

Gongliao grassroots activists sought to separate themselves from party politics. Having worked closely with DPP over the past decade, local activists found their protests dominated by political leaders. For years, villagers were encouraged to present their case using the vocabulary provided by politicians and academics. While the anti-nuclear movement brought the village’s plight to the public eye, it also deprived it of its true identity, reducing it to a political token imbued with the sense of confrontation and anger. The village existed in the public imagination only because of the nuclear power dispute. Its land, people, their everyday lives and emotions, were all eclipsed by the violence involved in the protest. When the campaign subsided with the DPP’s ascendance to power, Gongliao and its anti-nuclear case were quickly forgotten. For decades, the streets of Taipei were perceived by the locals as the centre of their protests. Yet by protesting in Taipei, locals had extracted themselves out of their own cultural context, occupied a space where they originally did not belong. The activists felt the need to return to their local community for new sources of moral authority. The authority was embedded in victimized villagers and their physical and cultural surroundings. An intimate contact with the locality constituted the basis of collective identity.

The place-based consciousness nevertheless was not acquired over-night. It took root among local activists through a long-term interaction between the local community and external groups. The Green Citizens’ Action Alliance (GCAA) had played an important role in depoliticizing local identity and cultivating a place-based consciousness among locals. Established as TEUP’s Taipei branch, GCAA split with it in 2000 because of different views on relations with the DPP. The GCAA represented a younger generation of environmentalists who were intolerant of the DPP’s deviation from its environmental promise. While the TEUP since 2000 was more intent on seeking a solution to the nuclear power problem by expanding participation in formal policy-making processes, the GCAA adhered to a bottom-up approach, believing the vitality of social movements lay with grassroots activism.63 Indeed, GCAA developed at a time when nativism became a new ideology for NGO leaders who sought independence from party politics. Originally motivated by a demand for community reconstruction in the mid-1990s, nativism, with the attention to local autonomy, face-to-face dialogue between activists and concerned local people, has been accepted by various social groups as an effective way to achieve real democracy.64

The GCAA evinced deep sympathy with locals’ frustration with the DPP and believed the locals deserved public respect:

In the past decade, we kept seeing Gongliao people travel to Taipei to join various street protests and return in disappointment. Politicians and public elites come and go, yet no one cares about the villagers who have been emaciated out of fatigue….Gongliao does not exist only for anti-nuclear purposes. We need to find the future orientation for local people. And in order to do so, we must return to the locality for energy and inspiration.65

|

Poster of How Are You, Gongliao |

One of the key leaders of the GCAA, Tsui Su-hsin, spent six years making the documentary, How Are You, Gongliao? Released in 2004, the film, for the first time, presented the anti-nuclear movement from the perspective of Gongliao villagers. Revolving around the 1003 event, Tsui challenges the commonly assumed “violent mob” image of local people and presented them as victims who were desperate to protect their homeland from a brutally imposed state policy. Such a discourse reversed the conventional moral judgement of the case established by the mainstream media. It authenticated the brutal violence involved in the local protest as a purer form of justice above law. Tsui’s documentary was widely screened domestically and internationally. Within the first year of its release, she had received over 1,300 postcards from audiences, particularly college students throughout Taiwan who expressed support for the villagers.66 Released at the time when the anti-nuclear movement was at low ebb, the documentary kept the issue within public consciousness. An experience once exclusive to elder Gongliao villagers had become a shared memory passed onto the youth.

Newly established connections with outside youth deepened the villagers’ understanding of the significance of the locality. It freed them from constant denial of the past and established among them a confidence of the local cause. While the DPP government made no effort to console Gongliao villagers after the setback in 2001, the GCAA approached villagers, shared their frustration and retrieved the locals’ anti-nuclear memories. After 2001, Gongliao became a destination of pilgrimage for ardent anti-nuclear activists and an educational centre for university activists. As Wu Wen-tung recalled, every year university student clubs (shetuan) visited Gongliao. Some students, frustrated with the decline of social movements during Chen Shui-bian’s rule, came to the township to share their distress with party politics and to seek inspiration.67 Through exchanging ideas with the social groups, villagers came to the realisation that local space should no longer be subordinated to the political centre in Taipei. The physical environment, the history of local people, the hardship they have been through as well as their continuous anti-nuclear commitment in daily life constituted a strong moral power beyond the locals’ expectation.

To further strengthen the local place as the base for disseminating anti-nuclear ideas, YASA leaders considered community building as their new focus. In 2005, Wu Wen-tung, then the head of YASA, together with a few primary school teachers, established a community newspaper, Gongliaoren (Gongliao people) in an attempt to reconstruct a common identity among the locals which had been lost in the decade-long anti-nuclear struggles.68

|

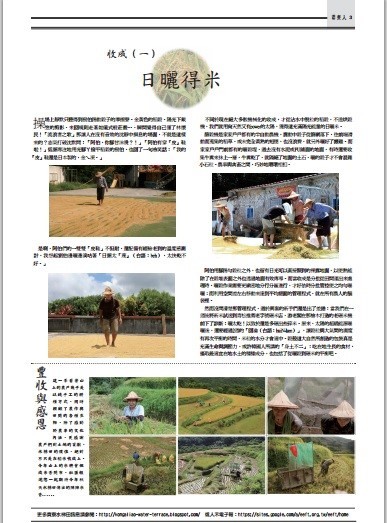

Gongliaren, No. 71, p.3 |

Gongliaoren featured local natural resources and the everyday lives of villagers. While the mainstream media portrayed local villagers as angry demonstrators in the streets who were ready to block traffic or confront the police, the paper returned the villagers to their geographical and social context and portrayed them as humble and diligent people, toiling away to maintain their livelihood. It should be noted that primary school teachers, a conservative group, were formerly absent from the anti-nuclear movement. Yet they were attracted to it because they were genuinely touched by YASA leaders’ strong commitment to the local community. One of the key editors, Lin Wen-tsui, acknowledged that the alternative way of protecting the local area instead of street protests echoed her similar aspirations: “A softer approach works better for me and I believe it is equally powerful.”69 Another editor, Wang Ching-e, also found it important to awaken villagers’ consciousness of place: “the more we knew about the local stories, the more strongly we felt the urge to protect it from a potential nuclear disaster.”70 While the paper started to attract villagers’ attention, local officials also showed interest in providing financial support for the paper. Yet editors insisted on protecting the paper’s independence from political infiltration.71

Information gathering was another way for activists to enhance the position of the locality. Retreating from the streets of Taipei, villagers developed a scheme of “on-the-ground supervision” (zaidi jiandu). They collected information on the harm 4NPP had brought to the local environment and daily life. Believing that the local sand beach was shrinking because of docks built by the power plant, villagers measured the level of sand regularly, and documented their results in photographs and detailed reports.72 Through informal social gatherings with plant workers, villagers were privy to the information about engineers’ change of the original construction plans and subcontractors’ cheating on materials.73 The locally acquired information was distributed to other communities by lectures organized by social organizations. This challenged the mainstream media’s accounts and provided an alternative source for public understanding of nuclear power issues.

Cultivating a shared lived experience was one of the important tactics that local activists adopted to mobilize outsiders, particularly young people. Here, “lived experience” stresses the importance of bodily sensations of material life in contrast to the experience we inherit from a secondary medium.74 The experience of the elderly, no matter how vividly it was represented on the screen, was an abstract and virtual presentation removed from its original social and natural context. A more concrete bond between the youth and local space needed to be established through personally acquired experience. And physical immersion into a local environment was conducive to building a tangible sense of connection and the care for local affairs and concerns. Indeed, the local environment created a habitus that cultivated informal associations among people. The associations, as Robert Weller stated, would provide small reservoirs of social capital that can multiply when political situations change.75 Where environmental movements elsewhere tended to aspire to “thinking globally, acting locally,” the Gongliao activists stressed the importance of “thinking locally” as the prerequisite for acting in a larger scale.

For years, YASA endeavoured to invite people from other parts of Taiwan to visit the village and considered it a measure to promote anti-nuclear ideas. This plan correlated with the community construction (Shequ yingzao) policy introduced by the central government in the 1990s.76 Although there is no clear evidence that YASA’s program was part of the local community construction project, the policy greatly reduced political hurdles for YASA to pursue its plan.77 The improved local infrastructure as a result of the policy also facilitated YASA’s program. In 2002, the Ministry of Communications introduced a tourism scheme that renovated the ancient Caoling trail passing through Gongliao. Taking advantage of the scheme, YASA organized hiking activities along the trail. Instead of taking people to the popular local tourism spots, YASA was keen to nurture a sense of intimacy between the outside visitors and the local land and its people. It guided visitors deep into the village, to walk along the ridges of fields and observe local villagers’ working among the green paddies.78 Walking itself became a process of communication between participants and the local space. The experience compounded by stimulation of multiple senses created a narrative and memory beyond what media could convey in a two-dimensional paper or screen. Villagers who were cognizant of local history, religious beliefs and natural resources volunteered as guides. For a remote village whose history and records rarely appeared in urban libraries or public readings, the local guides’ accounts together with the visitors’ personal observations often helped to form their initial understanding of the area. To enrich participants’ understanding of the locality and to establish a bond between a visitor and the village was exactly what the organizers wished to achieve. As a YASA leader explained, “Once they realize the value of the local area, they will inevitably care about its future.”79

The annual Hohaiyan Rock Festival provided YASA another opportunity to cultivate a shared lived experience. Initiated by independent music groups and the government of the New Taipei County in 2000, the festival grew into the biggest music festival on Taiwan. The festival required no entrance fee, fancy clothing or elaborate decorations. Such a plain style attracted thousands of young people. Although the festival had little to do with Gongliao’s anti-nuclear pursuit, the fact that it was held at the Fulong beach right next to the construction site of the fourth nuclear plant inevitably drew public attention to the local nuclear problem. Realizing that the popularity of the festival constituted a promising opportunity to promote anti-nuclear ideas, Wu Wen-tung approached the GCAA for assistance.80 The GCAA was careful not to cause distaste from the public who came to Gongliao primarily for fun. It first approached the music bands who were “opinion leaders” in the festival and tried to influence their views on the local anti-nuclear by inviting them to watch Tsui’s documentary.81 A band entitled 929 openly expressed their anti-nuclear stance before their performance in 2004, and this set off ripples of anti-nuclear appeals among singers and music producers in subsequent festivals. In recollection, 929 members confessed that they initially came to the festival with the simple goal of winning an award. Yet after witnessing the damage to the local environment and chatting with villagers backstage, they realized that an award was much less important than raising the audience’s awareness of the shrinking beach under their feet, the pollution of the sea, and the potential nuclear hazard caused by the power plant under construction nearby.82 The singer Wu Chih-ning, based on his experience in Gongliao, composed “We Don’t Want Nuclear Power Plants,” which became a famous anti-nuclear song repeated in various anti-nuclear campaigns.

The anti-nuclear issue gradually transformed from a political cliché into a popular cultural icon linked with the notion of “independent thinking,” “love of homeland,” and “rebellion” appreciated by the youth. In addition to the Hohaiyan music festival, CGAA started the annual “No Nukes” Anti-nuclear concert on the local beach which has continued since 2009. A “No Nukes” marching band composed by veterans of the wild strawberry student movement was formed in 2010. The band sought to boost local villagers’ anti-nuclear momentum by showing support for the local cause. It also sought to “open a new realm of political discussion through music and performances.”83 Indeed, local space had become the focal point for anti-nuclear activists to gather and experiment new movement strategies. The creative activities organized by NGOs changed the cultural context and discourse of the anti-nuclear movement-from a movement involving suffering, hardship and violence to an event featuring fun, creativity and independence. Engagement with local activism also constituted a source of political power that strengthened CGAA and other independent groups’ leading position in the anti-nuclear movement when political opportunity arose.

Revival of the Anti-Nuclear Movement

The Fukushima nuclear disaster in 2011 sounded a grim warning to Taiwanese society about the hazard of nuclear power. Living on an island that also sits in a seismic area, the Taiwanese strongly related Japan’s disaster to their own concerns for the safety of nuclear power. “What if the Fukushima nuclear disaster occurred in Taiwan” became a question that kept haunting the imagination of the Taiwanese. On 9 March 2013, over 220,000 people throughout the island marched in the streets protesting the government’s development of nuclear energy in the largest anti-nuclear demonstration in Taiwan.84 Yet the Fukushima Incident only changed people’s perception on what to protest, not how to do it.

|

Anti-nuclear Demonstration, March 2011 |

Post-Fukushima protests have many distinctive features developed during the dormant period of the movement. First, the DPP lost leadership in the anti-nuclear movement. While DPP leaders tried to relaunch the party’s visibility in anti-nuclear demonstrations immediately after the Fukushima Incident, younger generations of activists evinced distaste for DPP’s presence and coined the slogan “NPP4 is a joint venture of both the green and blue camp” in protest.85 (see Figure 5)86 During the 9 March demonstration in 2013, DPP members were instructed by Su Tseng-chang, chairman of the party, not to show the party flag, possibly under pressure from NGO leaders who opposed subordinating the anti-nuclear movement to partisan struggles. Indeed, anti-nuclear groups were no longer allies of political parties. They considered themselves part of the “citizen movement,” transcending division of blue and green camps. Independent NGOs, particularly the GCAA, became the new leaders of the movement.

Second, more and more artists and celebrities in entertainment circles joined post-Fukushima anti-nuclear activities. Their engagement turned the protests, which once focused on suffering, rage, and self-sacrifice, into a cultural carnival of youth. Protests in the form of pop concerts, poster design competitions and a petition of popular stars have replaced the traditional street demonstrations and sit-ins. The element of fun and leisure which used to be excluded or marginalized in the anti-nuclear movements has become an indispensable part to attract the participation of younger generations who would otherwise be put off by conventional street protests. Compared to the old generation of anti-nuclear protesters, artists emphasize the power of “softness” and emotions in political combat.

These distinctive features were not a sudden invention after Fukushima but were formulated during the so-called dormant period in the first decade of the twentieth first century. Ming-sho Ho, in assessing why Taiwan generated the strongest anti-nuclear sentiment in East Asia after the Fukushima Incident, argued that the outreach of activists after 2001, the rising social protests after Ma Ying-jeou took office in 2008, and the DPP’s inability to lead the movement attributed to the revival of the anti-nuclear movement.87 Yet the locals’ anti-nuclear experience and their new way of framing anti-nuclear actions should not be neglected. Their decades-long anti-nuclear journey provided the urban activists with a new perspective and language to repackage the movement. During this process, the local village also transformed from a marginal locale to the centre of the movement. Local space constituted a source of authority and authenticity for the anti-nuclear cause. GCAA’s long-term engagement with locals provided it the credibility to play a leading role in the new wave of the movement. As Tsui maintained, “no one has ever questioned our [GCAA] anti-nuclear intentions, because we have been through the most difficult days with the local people.”88 The network between locals, urban artists and university clubs formed during the last decade also constituted the social basis of the current anti-nuclear movements.

As a result of sustained public protests, the Ma Ying-jeou government, in April 2014, decided to seal off the 4NPP’s first reactor and halt construction of the second one, which was ninety per cent complete. The future of the power plant will be decided by a national referendum.89 Locals started to correlate this current development with Mazu’s message thirty years ago, that “the fourth nuclear power plant would be built, but not operate.” Indeed, locals are unsure about the eventual fate of the “big monster” (da guaishou, moniker of 4NPP) in their neighbourhood. Yet the strong anti-nuclear sentiments from civil society resonate with their anti-nuclear efforts that have sustained the rise and fall of the movement itself through years of setbacks and victories.

Conclusion

Local anti-nuclear protests were closely linked with partisan politics before 2000. Despite villagers’ awareness of local interests, locality for them was still an abstract notion subordinated to the political imagination centred on the state and the party. Local anti-nuclear resources were quickly absorbed into partisan struggles between KMT and DPP in the 1990s. Chen Shui-bian’s victory in the national election, however, failed to halt the construction of 4NPP. Due to the lack of a parliamentary majority and the DPP’s decision to seek support from business leaders, the party often conceded to the latter’s demand for development in a tug of war between environmentalists and the corporate world.90 To recover from the “betrayal” of the party, villagers returned to the local community to seek confidence and strength. Inspired by GCAA, they sought to free themselves from the framework of partisan politics, and convert the anti-nuclear movement into a cultural issue by creating a new image and interpretation of the local anti-nuclear movement. They focused on attracting young people to the local area and nurturing their lived experience as the basis for a common identity. Instead of appealing to the public’s “rationality” with the vocabulary provided by politicians and academics, they sought to evoke outsiders’ emotions and feelings based on their engagement with the local area.

Indeed, the change of direction was inspired by villagers’ renewed understanding of local space, as well as the political imagination of “centre” and “periphery” in their anti-nuclear journey. Before 2000, villagers believed that the centre of their protests lay in the streets of Taipei and success of their protests was closely linked with DPP victory in local and national elections. Disillusionment with party politics, however, galvanized them to reconsider the value of local place. The local environment as well as its history, social conditions and everyday life-style was the source of information and knowledge that redefined the moral ground, the context in which people considered nuclear power issues and the language activists used to mobilize public support. Indeed, local place had provided invisible cultural resources different from what the political opportunities and institutions could offer. While the political map of Taiwan has long been dominated by the division between the Blue Camp led by the KMT and the Green Camp led by the DPP, place-based consciousness provided an alternative way for society to re-imagine and approach politics.

Shuge Wei is a postdoctoral research fellow of the Australian National University, currently working under Prof. Tessa Morris-Suzuki’s project “Informal Life Politics in East Asia.” She received a PhD from the Australian National University and an M.A. from Heidelberg University in Germany. Her research interests include grassroots movement in Taiwan and China, China’s international propaganda policy, Chinese media, Sino-foreign relations during the inter-war period, and party politics of the Kuomintang government. Her recent publications include “Beyond the Front Line: China’s Rivalry with Japan in the English-Language Press over the Jinan Incident, 1928” in Modern Asian Studies and “News as a Weapon: Hollington Tong and the Formation of the Guomindang Centralized Foreign Propaganda System, 1937-1938” in Twentieth-Century China.

Related articles

- Mei-Chih Hu, Renewable Energy vs. Nuclear Power: Taiwan’s energy future in light of Chinese, German and Japanese experience since 3.11

- Andrew DeWit and Sven Saaler, Political and Policy Repercussions of Japan’s Nuclear and Natural Disasters in Germany

* This study is part of the Australian Research Council Laureate Project “Informal Politics in the Remaking of Northeast Asia: from Cold War to Post Cold War” led by Prof. Tessa Morris-Suzuki. I deeply appreciate the support of our research group and comments from the editor and the anonymous reviewer.

Notes

Xie Yun, “Fanhe chenggong,” United Evening News, 30 September 2000; Li Shuren, “Gongliaoren fang bianpao qingzhu,” United Evening News 27 October 2000.

Ming-sho Ho, “Weakened State and Social Movement: the Paradox of Taiwanese Environmental Politics after the Power Transfer,” Journal of Contemporary China, Vol. 14, No. 43 (May 2005): 340; “Taiwan’s State and Social Movements under the DPP Government, 2000–2004,” Journal of East Asian Studies, No. 5 (2005): 401–425.

Hsin-Huang Michael Hsiao, “Environmental Movements in Taiwan,” in Yok-shiu F. Lee and Alvin Y. So (eds.) Asia’s Environmental Movements (New York: M. E. Sharpe, 1999); Ming-sho Ho, “The Politics of Anti-Nuclear Protest in Taiwan: A Case of Party-Dependent Movement (1980–2000),” Modern Asian Studies, Vol. 37, No. 3 (2003); Pan Hui-Ling, “Taiwan fan Hesi yundong lichen zhi zhengzhi fenxi ” [Examining Anti-fourth-Nuclear-Power-Plant Movement in Taiwan], (Master thesis, National Taiwan University, 2007).

Benedict J. Kerkvliet, The Power of Everyday Politics: How Vietnamese Peasants Transformed National Policy (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2005).

Robert P Weller, Alternative Civilities: Democracy and Culture in China and Taiwan (Oxford: Westview Press, 1999).

Doug McAdam, Sidney Tarrow and Charles Tilly, Dynamics of Contention (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 12, 15.

Arif Dirlik, “Place-based Immagination: Globalism and the Politics of Place,” in Place and Politics in an Age of Globalization, Roxaan Prazniak and Arif Dirlik ed. (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2001),22.

Cheng Shu-li, “Shehui yundong yu defang shequ bianqian: yi Gongliao xiang fan Hesi weili,” (Social Movement and Community Transformation: A Case Study on the Anti-Nuclear Movement in Gongliao), (master’s thesis, National University of Taiwan, 1995), 93–94.

Ming-sho Ho, Lüse minzhu: Taiwan Huanjing yundong yanjiu (Greeen Democracy: Environmental Movements in Taiwan) (Taipei: Qunxue chubanshe, 2006), 59.

See Robert Weller and Hsin-huang Hsiao’s discussion on the importance of Western-educated academics in the early environmental movement in Taiwan, “Culture, Gender and Community in Taiwan’s Environmental Movement,” Environmental Movements in Asia, edited by Ame Kalland and Gerard Persoon, (Curzon Press, 1998).

Ming-sho Ho, “The Politics of Anti-Nuclear Protest in Taiwan,” 688; also see Ho’s discussion on the transformation of intellectuals from “man of ideas”(linian ren) to “man of politics” (zhengzhi ren), in “Taiwan huanjing yundong de kaiduan: zhuanjia xuezhe, tangwai, caogen,” (The origin of environment movements in Taiwan: intellectuals, Tangwai and grassroots) Taiwan shehuixue, Vol.2, (December 2001): 97–162.

Chao jui-chang, head of Zhenli borough, former head of YASA, and Chen Shi-nan, former head of Gongliao township, interview by author, Gongliao, 16 December 2014.

Chao jui-chang and Chen Shi-nan, interview by author, Gongliao, 16 December 2014; Wu Wen-tung, former head of YASA, interview by author, Gongliao, 17 December 2014.

Robert Weller and Hsin-huang Hsiao, “Culture, Gender and Community in Taiwan’s Environmental Movement.”

Chao jui-chang and Chen Shi-nan, interview by author, Gongliao, 16 December 2014; Lin Fu-lai, interview by author, 17 December 2014. Many personal and institutional blogs also document the divination. See hereand here.

Chao jui-chang and Chen Shi-nan, interview by author, Gongliao, 16 December 2014; Wu Wen-tung, interview by author, Gongliao, 17 December 2014.

Chao jui-chang and Chen Shi-nan, interview by author, Gongliao, 16 December 2014; YASA’s financial report of 1995, The Eighth Conference Newsletter of YASA, 10.

Chen Mingtong, Paixi zhengzhi yu Taiwan zhengzhi bianqian Factional politics and the change of Taiwan political environment] (Taipei: Yuedan chubanshe gufen youxian gongsi, 1995), 5–10; Joseph Bosco, “Taiwan Factions: Guanxi, Patronage, and the State in Local Politics,” Ethnology, Vol. 31, No. 2 (April 1992): 157–158.

See the origin of Xinpai and Jiupai in Gongliao, Cheng Shu-li, “Shehui yundong yu defang shequ bianqian: yi Gongliao xiang fan Hesi weili,”68-71.

See detailed discussion on the factional division between Xinpai and Jiupai, in Cheng Shu-li, “Shehui yundong yu defang shequ bianqian: yi Gongliao xiang fan Hesi weili,” and Chen Chien-chi, “Zhengzhi zhuanxing zhong shehui yundong celue zizhuxing: yi Gongliao fan Hesi yundong weili” (Strategy and Autonomy of Social Movements in Political Transition: A Case Study of the Anti-Fourth Nuclear Power Plant Project Movement in Gong-Liao) (master’s thesis, Soochow University, 2006), 57–58.

See Cheng Shu-li’s detailed research on tensions between the Old and New factions within YASA. Cheng Shu-li, “Shehui yundong yu defang shequ bianqian: yi Gongliao xiang fan Hesi weili.”

Source based on Chen Chien-chi, “Zhengzhi zhuanxing zhong shehui yundong celue zizhuxing: yi Gongliao fan Hesi yundong weili,” 58. Data after 2000 is collected by author based on interview with Wu Wen-tung, 17 December, 2014.

On the different policies of KMT and DPP see Richard C. Bush, Untying the Knot: Making Peace in the Taiwan Strait (Washington: Brookings Institution Press, 2005), 164–198.

-Nuclear-Power-Plant movement in Taiwan,” (master’s thesis, National Taiwan University, January 2007), 71.

Shen Ming-chuan,”Fugong? Taidian zhuguan: huikuijin jiang hufu,” United Evening News, 15 Jan 2001.

Karl Mannheim (edited by Kurt H. Wolff), From Karl Mannheim (New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 1993), 365.

Ya-Chung Chuang, “Democracy in Action: The Making of Social Movement Webs in Taiwan,” Critique of Anthropology, Vol. 24 (3): 247.

Tsui Su-hsin, “Gongliao sheng yu si: Gongliao de fanhe yundong jilu,” (master thesis to Shih Hsin University, 2001 June), 10.

“Lived experience” was borrowed from Brad Weiss’s concept of “lived world” which he coined to describe the way the Haya people of north-eastern Tanzania inhabit and experience their environment. See Brad Weiss, The Making and Unmaking of the Haya Lived World: Consumption, Commoditization, and Everyday Practice, (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 1996). Also see Tessa Morris-Suzuki’s emphasis on the importance of the “lived world” in shaping our political identities, in “For and Against NGOs: The Politics of the Lived World,” New Left Review, No. 2 (March-April 2000): 63-84.

Robert Weller, Alternative Civilities: Democracy and Culture in China and Taiwan (Colorado: Westview Press, 1999).

For more on the origins of the community construction policy, see Huang Li-ling, “Xin guojia jiangou zhong shequ juese de zhuanbian: shequ gongtongti de lunshu fenxi,” (The Transformation of Community in the Construction of a New Nation: Analysis on Community Building) (master’s thesis, National Taiwan University, 1995).

“Community construction policy” was absent from the vocabularies of my informants when they recollected their anti-nuclear experience.

Ming-sho Ho, “The Fukushima Effect: Explaining the Resurgence of the Anti-Nuclear Movement in Taiwan,” Environmental Politics, Vol. 23, No. 6 (May 2014).

Ming-sho Ho, “Weakened State and Social Movement: the Paradox of Taiwanese Environmental Politics after the Power Transfer,” Journal of Contemporary China, Vol. 14, No. 43 (May 2005).