Abstract

This article examines images of migrant workers and brides in recent South Korean films in order to demonstrate how popular media can complicate the issue of multiculturalism in Korea, and to problematize the ethnic and gender hierarchy embedded in multicultural policies and in the social fabric of Korean society.

Introduction: Behind Nation Branding

The ways Hallyu is received in other East Asian and Southeast Asian countries show that audiences’ involvement in transnational cultural productions goes beyond consumption: as Chikako Nagayama, Millie Creighton, and Mary J. Ainslie discuss in this issue, Hallyu often triggers the audiences’ interest in actively engaging with domestic social issues and inter-regional politics. By paying attention to popular culture’s capability to create communicative social space, this paper seeks to answer what role Korean film plays in articulating discourse about multiculturalism within Korea’s borders.

Although Korean films have not enjoyed global popularity as widely as Korean TV dramas and K-Pop, they have come into the spotlight in global entertainment industries by winning numerous awards at major international festivals in the last decade. Domestically speaking, there was sharp hike in the market share of Korean-made films, jumping from around 20 per cent in 2001 to reach 59.1 per cent in 2013 (Korean Film Council). Since the early 2000s, several domestically produced films in Korea have attracted audiences of over ten million into theatres.1

This phenomenal consumption level was partially spurred by the state’s active support for cultural industry since the Lee Myŏngbak administration (2008-2013) though it must be noted that the suppression of cultural productions that contain social criticism of the state’s domestic policies and practices has intensified over the last decade as well.2 Nonetheless, it was also during the Lee administration when multiculturalism gained cultural currency since the state promoted many initiatives on multiculturalism through various venues including media. In this essay, I problematize both the state’s multicultural policy and also media representation of foreigners in Korea through examining recent popular Korean films that feature migrant workers and foreign brides. The state’s emphasis on migrant brides as “mothers to be assimilated” demonstrates the gendered politics in its immigration policy, which prioritizes the assimilation of migrant brides while systematically pushing male migrant workers to return to their homelands. I will review the state’s assimilationist and patriarchal multicultural policies and the stereotyping of foreigners in Korean media; and investigate the ethnic and gender hierarchy embedded in these films. The films discussed in this paper feature a layered racial discrimination that also intersects social divisions in Korea-divisions that were created not by ethnic and patriarchal nationalism alone but also by domestic economic conditions. More importantly, these films gained significant popularity, which motivated many audiences to actively discuss multiculturalism using public communication channels. Despite their problematic representation of ethnically and culturally different Others, these films articulated issues that advanced the multicultural discourse in ways that engaged both migrants and Koreans.

The Multicultural Discourse in Korea

In the last twenty years, intra-regional immigration to East Asian countries-Japan, Korea, and Taiwan in particular-have increased substantially. Scholars have presented three attributes that are responsible for the increase of both migrant workers and migrant brides in these East Asian countries: the labor shortage, the low fertility rate, and an aging population (Parreñas and Kim 2011). However, these attributes do not adequately explain the flow of capital and commodities into Korea that also have been prominent in the last decade (Lie 2014, 18), which are due to Korea’s attempt to globalize the tourism and education industries. The numbers of foreign students and tourists are increasing dramatically with the state’s attempts to “internationalize” university campuses and boost the domestic economy through tourism (Chŏng 2014, 447–49; Korea Tourism Organization 2015).3

Less welcome are the migrant workers who come to Korea mainly from China, Southeast Asia, South and Central Asia, and South America, and most of them are employed in low-paid and low-skilled jobs in smaller firms (Kim and Oh 2011, 1564), whereas foreign brides arrive in Korea mainly from China, Vietnam, and the Philippines (Kim and Oh 2011, 1571). The approximate number of migrant workers and migrant brides in Korea is over 1.5 million in total, comprising almost 3 per cent of the whole population in South Korea as of 2013 (Korean Statistical Information Service, hereafter KOSIS). The rate of international marriages has been well above 10 per cent of all marriages every year since 2005, although it dipped to about 8 per cent in 2013, the lowest over the last ten years. This is one-sided: while the rate of international marriages between Korean men and non-Korean women has been increasing substantially, the rate of marriages between Korean women and non-Korean men has not, comprising less than 30 per cent of international marriages over the past ten years (KOSIS).4 This pattern has resulted from the difficulty men in rural farming villages have in finding native Korean women, who tend to seek urban lifestyle and jobs in cities rather than settling into farming communities.

One notable trend in the influx of foreigners into Korea is the large number of ethnic Koreans (a.k.a. chosŏnjok) from China who move to Korea to settle or work. As of December 31, 2011, there were about 470,000 chosŏnjok living in Korea (Kang 2012, 109). The media exposure of their presence is often directed towards creating a nostalgic imagination of the “shared bloodline” between the chosŏnjok in China and South Koreans. For example, when a young man from Yanbian, Paek Ch’ǒnggang, won a national singing competition, Widaehan t’ansaeng (A great birth) in 2011, the hosting broadcasting company, MBC, actively produced an image of him as a third-generation Korean whose “Korean dream” had come true. Paek’s experience of poverty was emphasized, portraying his dream of living with his parents, whom he had been separated from at the age of nine. His parents, who went to Korea to make money, were also invited to the audition studio to stage a dramatic family reunion-a reunion that symbolically extends to a reunion of once displaced ethnic Koreans with the Korean soil.

However, this romantic image of reunion can vanish quickly when chosŏnjok commit crimes, to be replaced by charges of disloyalty toward Korea. A chosŏnjok worker, O Wŏnch’un, is such a case. O murdered and mutilated the body of a young South Korean woman in April 2012. Media reported that he killed the woman after an attempted rape, yet the mutilation of her body generated numerous unfounded conspiracy theories tying the murder to the illegal sale of human organs and the existence of an underground human meat market. Although the ratio of crimes committed by foreigners is significantly lower than the crimes committed by Koreans, only accounting for about 0.7 per cent of the crimes committed in 2010 (Korean Statistical Information Service), the media’s sensationalizing of migrant workers as a potential criminal group has given rise to xenophobia based on fear of crime.

As many ethnic Korean women from China who are married to Korean men testify, the discrimination against them by their Korean family and spouses is based on the economic disparity between Korea and China and the deeply entrenched patriarchal family relations in Korea (M. Kim 2014; Freeman 2011). This contrasts with Korea’s eager attempts to engage ethnic Koreans in advanced countries, especially those who have prominent positions in their own societies. A South Korean adoptee to the US, Toby Dawson, is just one example: this medal-winning skier from the 2002 Winter Olympics was welcomed by the Korean government and was offered the role of honorary ambassador for Korea’s bid to host the winter Olympics.5

The influx of migrant workers and foreign brides has earned great attention from academics and policy-makers in Korea since the early 2000s. The Korean government reacted to the country’s changing demographics by adopting immigration and multicultural policies from other countries such as the US, Canada, and Australia. (Lim 2014, 38–42). The policies, however, are concentrated on the accommodation of foreign brides while no serious consideration is given to migrant workers. The state’s multicultural policy is assimilationist (Lim 2014; M. Kim 2014; Kim and Oh 2011) and patriarchal (Lim 2014; M. Kim 2014; H. Kim 2014), which resulted in a series of problems for interracial families as well as migrant workers. The government’s immigration policy is concentrated on the “multicultural family,” accommodating their needs in education, settlement, and job training, whereas its policies on migrant workers are lacking to the point of being dreadful. It seems clear that the main object of the government’s multicultural policies excludes migrant workers and domestic Koreans: the term “multiculturalism,” in other words, is mainly used for “multicultural families,” who will learn how to integrate into the Korean society through acquiring language and job skills. Migrant workers are rather administered separately by labor law, which generates serious constraints on these workers. As I will describe in the later section of this paper, the law turns many workers to be exposed to employers’ exploitation; and it makes them extremely difficult to obtain immigrant status. Furthermore, the government’s education program for “multicultural families” is uniform across the country: mainly geared towards multicultural families in rural areas, it lacks curriculum suitable for multicultural families and migrant workers in cities (S. Kim 2011, 184-7).

The exclusive focus on interracial families in multicultural and immigration policies reveals that the term tamunhwa (multicultural) is problematic: it is used in a narrow sense, failing to embrace those who do not belong to the category of “tamunhwa families,” such as migrant workers and foreign students. The result of this failure is a public misconception of migrant workers and foreign students as unwelcome additions to society and an economic burden on taxpayers. What is also fundamentally missing in the state policies is an attempt to connect these tamunhwa families with Korean communities, which could build a foundation to enhance the mutual understanding between them (S. Kim 2011). The absence of this connection in turn affects the lives of mixed-race children significantly.

Besides the unaccommodating government policy, discrimination against migrant workers and foreign brides on an everyday life level is alarmingly widespread. Foreign brides often face verbal and physical abuse from their spouses and in-laws (Freeman 2011; M. Kim 2014). It has been reported that most of these children experience bullying at schools because they are different, and due to this bullying, these children are discouraged from obtaining higher education, limiting their choices for future careers (Kim, Chǒng, and Yi 2012).

And it is extremely challenging for migrant workers to find long-term employment or an opportunity to change their status to immigrant due to the draconian labor laws. Media have also played a significant role in producing biased views on migrant workers and foreign brides though right-wing media are taking a leading role in producing such views. The right-wing newspapers, for example, tend to focus on violations of labor law and crimes committed by migrant workers, while foreign women and wives are represented as an object of assimilation. Progressive newspapers, on the other hand, focus on violations of human rights committed by native Koreans against foreigners (Im 2012).

Negative views of migrant workers have also grown as jobs have become less well-paid or secure, due to the neoliberal economy. The process of neoliberalization has accelerated since the Myung Bak Lee administration, widening the gap between the rich and the poor. The unemployment rate increased from 3.2 per cent to 4.5 per cent between 2007 and 2011; there was a massive replacement of regular workers with temporary employees and day laborers; the relative poverty rate jumped from 7.8 per cent in 1990 to 14.9 per cent in 2010; and 8.4 per cent of the whole population lived below the poverty line in 2010 (Suh, Park, and Kim 2012, 842). As Harvey argues, neoliberalism “has proven a huge and unqualified success” for creating an enormous gap between the haves and have-nots (2009, 67), yet it has done very little for those who have been proletarianized during the process.

This is the context for the films analyzed here. They are noteworthy for the following reasons. First, they provide a critical perspective on both state policies and social discrimination against migrant workers and foreign brides by realistically rendering the struggle to adjust in Korea. Second, the films reflect current social and economic issues that concern both foreigners and Koreans, such as the worsening labor market. Third, film viewers, both Koreans and international migrants in Korea, really responded to these films. Despite the biased representations of foreigners in some of these films, they deserve our attention because they generated so much popular response from the audiences regarding multiculturalism.

Hypermasculinity and Suppressed Manhood: Representations of Migrant Workers

Until Korea and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) normalized their diplomatic relationship in 1992-thus encouraging many chosŏnjok living there, especially those in Jilin Province, to migrate to Korea in search of work-the lives of chosŏnjok in Yanbian, in Jilin was virtually unknown to Koreans. But since the early 1990s, chosŏnjok from the PRC have been providing low-wage/low-skill labor in Korea, and cultural misunderstandings about these ethnic Koreans have generated very biased views about them. More than a half-century of separation between their ancestral homeland and their living experience in the PRC has created a wide gap between Korea and Yanbian. The main source of the discrimination, however, is the economic disparity between Korea and the PRC: Koreans’ view of chosŏnjok is condescending, treating them as poor neighbours who are just taking advantage of the economic system of Korea.

|

Figure 1. “Chǒnghak” in The Yellow Sea |

Two of the recent blockbuster films that portray chosŏnjok from Yanbian Prefecture are The Yellow Sea (Hwanghae, dir. Na Hongjin, 2010) and New World (Sin segye, dir. Pak Hunjung, 2013). Both are gangster films, and feature a hopelessly dark side of the lives of ethnic Koreans in the PRC who are involved in criminal activities such as human trafficking, human organ trafficking, and smuggling drugs into South Korea. In The Yellow Sea, a poor taxi driver in Yanbian, Kunam, becomes a hit man in order to pay his debts. However, because his ulterior motive is to find his wife-with whom he lost contact when she went to Korea to make money-Kunam accepts an offer from a fellow ethnic Korean man, Chǒnghak, to kill a man in Korea. Kunam cannot accomplish his double mission; he can neither kill the man nor find his wife. As a consequence, he is chased by Chǒnghak (fig. 1), whose personality is portrayed as almost demonic. Chǒnghak doesn’t flinch when he swings his ax at people, creating gruesome scenes throughout the film. Even when he is fatally wounded, he doesn’t give up his pursuit of money.

Major newspapers published ambivalent reviews of The Yellow Sea. While film critics focused mostly on the director’s contribution to the Korean thriller genre with his well-constructed action cuts, newspapers criticized the valorized violence (O, December 23, 2010). The film was quite successful; it drew 2.4 million viewers to the theatres (Korean Film Council). Thanks to this popularity, the image of dangerous and violent ethnic Koreans committing crimes is often invoked whenever a report of ethnic Koreans’ criminal activities appears.6 It is rare to find reviews that discuss the representation of ethnic Koreans in any other way in the Korean mainstream media.

However, the film created a big stir in chosŏnjok communities both in Korea and China, who criticized the misrepresentation of ethnic Koreans and their lives. An ethnic Korean graduate student at Korea University expressed concern over the film’s exaggeration of poverty and its description of the life of ethnic Koreans in both China and Korea. As he explained, “we are not poor, we just come to Korea because we can make more money…and we are not discriminated against in China as described in the film since the Chinese government’s multicultural policy ensures our right to preserve language and culture” (No 2011). Other chosŏnjok also expressed their discomfort over seeing their image fictionalized for the sake of commercial profits.

In the film, the chosŏnjok are far more violent than the native Korean gangsters in the film, resonating with a rhetoric that often surfaces in newspapers and social media when describing chosǒnjok. Furthermore, in contrast to the shabbily dressed chosŏnjok characters in dark spaces, such as basements and construction sites, their South Korean partners appear in stylish dress and drive top-notch cars in a gentrified urban landscape. Korean gangsters in New World are particularly chic, accentuating the contrast with chosŏnjok characters, who have a country-bumpkin-like appearance and exhibit impulsiveness in both speech and behavior.

|

Figure 2. The “Yanbian beggars” in New World |

What is also disturbing is the erasure of the chosŏnjok characters’ individuality: in New World, they are referred to as “Yanbian beggars” (fig. 2) who will do virtually anything for money. Further, the “number two” of a Korean crime organization in the film is an ethnic Korean from the PRC, a man with the ambition to become the leader of the organization. Despite the series of violent acts he commits, he does not show any affinity with China until he awaits his own death on a hospital bed. This is the first and last time he speaks Mandarin in the film, which is rarely seen in Korean films or TV shows. This is a strange reversal of the character’s identity. He has performed his Korean identity all along, while the impression of him as ethnic Korean has loomed around him because of the exaggeration of his dowdy clothes and accent. And yet, when the character speaks in Mandarin the viewers realize a boundary that they did not recognize before. In turn, the main character, an undercover policeman, who listens to the dying man’s Mandarin words, turns out to be ethnic Chinese in Korea: although their ethnic identity differs, their strong bond is affirmed through the same language. The vague notion of the “sameness, but not quite the same” is shattered at this moment: the familiar Other becomes unfamiliar and the previously held perception of their identities is seriously challenged. Although these characters do not display their consciousness of being ethnic Others in the Korean society, this single scene highlights how they “betray” the audience’s previously formed knowledge about their identity: the Koreanness both these characters have performed up to this scene suddenly becomes questionable.

It is basically impossible to distinguish ethnic Koreans born in China from ethnic Koreans born in South Korea by their looks because of their similar physiognomy, and ethnic Koreans from China and Koreans from North Korea deliberately attempt to follow South Korean consumption trends to pass as middle-class Koreans (Chung 2008, 18). And yet, as these people testify, Koreans’ unwillingness to recognize their cultural difference contributes to the continuing construction of the image of ethnic Koreans as dangerous Others.7 Male ethnic Koreans hardly appear in any other cinematic genres beyond gangster films, and media often inflate their criminal activities in Korea, linking social unrest to the presence of these “criminals.”

The representation of migrant workers from other parts of Asia in film is no better. Unlike chosŏnjok, who can pass as Koreans at least at first glance, Southeast Asian and South Asian workers are visually noticeable. This visibility draws a cultural boundary between them and native Koreans, and Koreans respond poorly to the relatively distant cultures they carry with them. This gap creates multiple barriers that deter Koreans from communicating with them. Migrant workers are often exposed to physical abuse from their employers, violations of their employment contracts, and sexual harassment, among other things (Amnesty International Korea 2015). Abuse from employers often derives from the labor regulations on migrant workers, especially the training system that existed between 1993 and 2004. This system defined migrant workers as trainees, justifying the low wages, the lack of health insurance, and the lack of payment for overtime work. This system was revised in 2004 in order to improve the work and living conditions for migrant workers. However, the regulations still limit the workers’ freedom to transfer workplaces, and upon the completion of the three-year maximum visa period, they are given only two months to obtain a new employment contract. These conditions have resulted in workers losing their legal status when they continue to seek employment in the underground economy (Chŏn 2010).

Unlike the violent image of chosŏnjok in gangster films, Southeast Asian and South Asian migrant workers are represented as illegal aliens who are physically weak, innocent, comical, and emotional. Given these attributes, it is not surprising that comedy drama is the main cinematic genre where migrant workers’ lives in Korea and their connection to their home countries are portrayed. However, unlike the gangster films, these comedy films often contain critical views of the Korean labor market, racial discrimination, and mono-ethnic nationalism, all of which are imbued with humor and satire.

The general public and media in Korea tend to respond sensitively to issues surrounding the labor market since the job shortage has become a serious social issue, especially after the financial crisis in 1997. In 2011, although the total unemployment rate was 4.5 per cent, as noted above, among young people it was much higher, reaching almost 10 per cent (Korean Statistical Information Service). The comedy, Banga Banga (He’s on Duty, dir. Yuk Sanghyo, 2010) is worth mentioning for its handling of the cut-throat competition in the job market and its portrayal of the lives of migrant workers in Korea. In the film, a young Korean man is employed in a furniture factory despite his wish to get a white-collar job. He is not able to get a job in any other sector due to his “not-so-impressive resume.”

A bigger obstacle in the way of employment, however, is his appearance. He is described as “unattractive” because of his “short height” and “dark-skinned, ugly face.” In South Korean society, performing one’s social status through one’s looks has been considered important-and people’s obsession with obtaining such looks has resulted in widespread cosmetic surgeries among young women and men there (Elfving-Hwang 2013). While a tall man with white and smooth skin has become a “standard of beauty,” this young man in the film stands on the opposite end of that “standard,” and so fails to give a “good impression” to job interviewers.

Realizing that he has a “South Asian look,” he disguises himself as a Bhutanese in order to get employed in a factory that hires mainly migrant workers. He names himself Banga, since the name has a “South Asian flavor”-the term is also an abbreviated form of bangawŏyo, meaning “nice to meet you” in Korean: a satirical twist that implies the unwelcoming atmosphere of Korea towards migrant workers. He works with fellow migrant workers in the factory, where, luckily, Banga is the only worker “from Bhutan,” thus securing his fake identity.

|

Figure 3. Banga disguised as Bhutanese |

The Korean man’s mimicry to pass as Bhutanese, with his “South Asian–like” dress and the strangely exotic Korean accent that he puts on, is painfully depressing. Throughout the film, Banga adopts a Muslim-like fashion code with his clothes and skullcap despite the fact that Buddhism is the state religion in Bhutan (fig. 3). This incorrect dress code could be translated as a derogatory representation of the Bhutanese, especially considering the fact that the main character chose this disguise because virtually no one in the movie is informed about the Bhutanese people and their culture. While such ignorance of the culture of Others points to the general public’s disinterest in Others in their society, it also tells the audiences about the reality of the job market where such an extreme measure has to be taken in order to advance oneself in the society.

Banga slowly builds friendships with other workers who express to him their discontent with Koreans and Korean society. Finally, Banga becomes one of them as a fellow worker, yet he is not one of them: he crosses his double identities, first in order to make living, and later in order to fight for them. One of the highlights of the film is the coarse language the characters use in their daily lives. Banga’s fellow co-workers, thanks to their exposure to verbal abuse at work, have “studied” many offensive and derogatory terms in Korean. Banga in turn teaches Korean foul language to newcomers to prepare them to “communicate” with Koreans in their workplaces.8

Even though it was a low-budget film, Banga Banga was quite popular, drawing about 800,000 viewers (Korean Film Council). Major newspapers, both conservative and progressive, published favorable reviews of the film, and many audiences expressed shame at the racial discrimination against migrant workers as well as the serious human rights violations they face. Some of the reviews from progressive newspapers and responses from audiences also are noteworthy for their criticism of the orientalist gaze on the workers. They expressed discontent with the misrepresentation of the workers’ cultural identity, starting with the presentation of ethnic food that does not match the workers’ culture of origin, and moving to the ways that the main character’s sympathetic gaze on workers dilutes their political agency.9 It does so by reinforcing the cultural hierarchy embedded in the gaze, predetermining the social position of the workers as lower than that of Koreans.

|

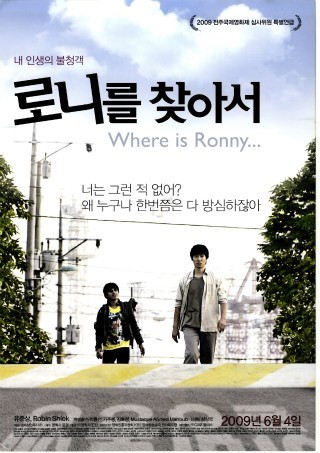

Figure 4. Ttuhin and Inho in Where is Ronnie… |

Another comedy that deals with illegal migrant workers is Where is Ronnie… (Roni rŭl ch’ajasŏ, dir. Sim Sangguk, 2009), which portrays a transformation of hatred to friendship between a Bangladeshi worker, Ttuhin, and a Korean man, Inho. It is set in Ansan City, a suburb of Seoul, which has been an industrial area since the mid-1970s. It is now also known for its large population of migrant workers. Inho is a Taekwondo master whose studio is in Ansan. In front of many people, including his young pupils, however, he loses a match to a Bangladeshi man called Ronnie. In order to recover his damaged ego, Inho searches for revenge, but instead he befriends Ttuhin on the way.10

Inho’s defeat in the Taekwondo match deconstructs the chauvinistic nature of ethnic nationalism. Although Taekwondo is associated with the ancient history, legends, and myths of Korea (Moenig 2015, 189), it is a relatively modern form of martial art that developed from karate techniques in the 1940s. The vestiges of the Japanese martial art, however, have been thoroughly rejected by Taekwondo practitioners (Moenig 2015, 187–89). Instead, Taekwondo has become a symbol of Korean national pride for its indigenousness and international recognition.

Inho’s plan to defeat Ronnie in front of a Korean audience is shattered, leaving with him an intense feeling of shame and anger. Inho is emasculated not only by the shameful event that destroyed his reputation but also by his constrained economic condition. His obsession with locating Ronnie in order to compensate his damaged ego grows. However, as he searches for Ronnie, he discovers the changed landscape of the city he has not noticed before. The kind of community he had in mind has never included migrant workers and their families: the Korean community considers people like Ronnie “temporary dwellers.” Through Ttuhin’s help, Inho begins to see the reality of the lives of these workers in his community.

Ttuhin refuses to be seen as a victim. He is an intelligent young man with a good education in his native country. But he knows that his background will be useless in Korea, where he will be employed in a low-skilled/low-paid industry. But he is optimistic about the future, that is, going back to his country with enough money to support his family there. Nonetheless, his handling of various challenges is not rendered in a sympathetic way; rather, Ttuhin’s optimism and humor inspire Inho, who is also having a hard time looking after his family. Inho’s friendship with Ttuhin continues to grow to the point where he tries to stop Ttuhin from being deported, but to no avail. This buddy-movie-like comedy focuses on the friendship that is being built between the two men. This film received favorable reviews from critics and audiences and it became popular among migrant workers themselves when it was screened in their communities and at the Migrant World Film Festival in Korea.11

The impact of these two comedy dramas is meaningful, first because they presented forms of racial discrimination in a straightforward manner, but humorously, so that the audiences recognized them without resistance. Second, they created a communicative space where the audiences engaged with the issue of discrimination in the public media network. Unlike the hypermasculine representation of chosŏnjok violence, which reinforces the foreignness of the familiar Others in gangster films, the two comedies show the emasculated Korean men discovering some common ground for building a deep and meaningful communication with Others. Albeit with the danger of affirming the stereotypes, these films opened up a new window for critiquing Korea’s reception of foreigners on a deeper level.

Representation of Female Immigrants

Naturalized “white Koreans” of European and American origin can perform their citizenry in a safer social environment than can non-white migrants to Korea. It is rare to find negative responses from the general public to white migrants’ performances as naturalized Koreans. A German-born Korean citizen, Bernhard Quandt, who was the CEO of the Korea Tourism Organization from 2009 to 2013, is a good example. He changed his German name to a Korean one, Lee Ch’am, which successfully publicized his love for Korean culture and dedication to improving the image of Korea in international communities.

However, non-white Korean citizens, like migrant workers, are often positioned in difficult situations, constantly being looked at with suspicion. In particular, Koreans’ suspicion of people of East Asian and Southeast Asian origin can easily turn to xenophobia, as seen in the case of Yi Jasŭmin, a woman from the Philippines who became a Korean citizen through her marriage to a Korean man. Yi was later elected as the first non-ethnic Korean proportional representative member of the National Assembly in South Korea. When she was running for a seat in parliament in 2012 as a candidate of the ruling party, Saenuri, she received numerous threats and discriminatory notes from Koreans. She believes that she and her children would have faced much less discrimination if she were a white woman (Yi 2013).

|

Figure 5. Yi Jasŭmin in Wandǔgi |

A year before her entry into Korean politics, Yi Jasŭmin played the role of a Filipina mother of a biracial youth in the film Wandǔgi (2011, dir. Yi Han), based on a bestselling novel with the same title by Kim Ryŏryŏng. In the film, a youth named Wandǔgi is delinquent and seems to have no prospects for his life. Wandǔgi, his humpbacked father, and his adopted uncle, who has a developmental disability, live in a poverty-stricken neighborhood inhabited by many migrant workers from Southeast Asia and South Asia. Wandǔgi has no memory of his Filipina mother since she left him when he was still an infant. The disappearance of Wandǔgi’s mother has to do with his father’s decision to “let her go” because he couldn’t tolerate the discrimination his wife faced. Wandǔgi, however, is able to meet her through his teacher’s help. After spending some difficult time coming to terms with her sudden re-appearance, Wandǔgi and his family decide to live together again.

Despite the government’s focus on multicultural families, it is rare to find popular films that deal with them. Wandǔgi is the only Korean feature film that portrays a multicultural family I have found so far. It became hugely popular, drawing almost five million viewers to theatres (Korean Film Council). Responses to the film were mainly positive, and many viewers stated that the film made them think more seriously about the social problems facing migrant workers and tamunhwa families. The film draws its strength by showing the similar economic conditions faced by these workers, tamunhwa families, and Korean families. Wandǔgi’s Korea-born neighbors, for example, do not seem to have better prospects for the future; they too are socially marginalized by poverty and disability, enabling viewers to identify with the figures in the film. Wandǔgi displayed a potential to bridge the distance between visible minorities and Koreans through the audience’s recognition of their own underprivileged status, just like Wandǔgi and his family. In this regard, class plays a crucial role, linking the underprivileged races or ethnic groups with underprivileged classes, which in turn could encourage a coalition of these groups for demanding equality (Higham 1993, 196).

Nonetheless, Wandǔgi does not get along with others in school and often gets into trouble for his rebellious nature. This problem also resonates with real-world conditions. In fact, a survey shows that a significant number of biracial children have difficulty in their school environment. For example, 37 per cent of young biracial children in Korea have experienced bullying in school, and at times even teachers contributed to the bullying by openly discriminating against them in classroom situations (Y. Kim 2012). Further, only 85 per cent of these children finish high school and 49% enter college, whereas the rate is about 10 per cent higher in each category among native Korean students (KOSIS). The divorce rate for international marriages is about three times higher than that of native Koreans. Female migrants’ cultural differences are often ignored and their different cultural practices are not encouraged in their households (M. Kim 2014). This kind of living environment at home and at school becomes a barrier for these children, keeping them from developing a sense of membership in Korea.

Ironically, foreign-born women in tamunhwa families whose looks are not distinctive face their own special challenges, and are rarely portrayed in public media, despite the fact that the majority of these women are Chinese nationals (H. Kim 2006, 57); TV dramas and variety shows predominantly deal with women from Southeast Asian countries, such as Vietnam and the Philippines. This pattern became prominent around the time when the government began to implement multicultural policies. As Kim Hyesun points out, multiculturalism did not become a public issue until the number of individuals belonging to racially different groups began to increase, thus making the foreigners “visible” (2006, 52).

Popular media has played a significant role in visualizing foreign wives as uneducated and poor women who become an object of assimilation. As Wandǔgi’s father tells his son, Wandǔgi’s mother obtained high education in her country, contradicting the widespread stereotype about these women. Yet, despite her educational background and her long-term stay in Korea, the mother’s appearance in the film is not any different from the stereotype of women from Southeast Asian countries. Several TV dramas, such as In Namcn’on Across a Mountain (2007–present), The Golden Bride (2007–8), and Likeable or Not (2007–8) in particular, feature the assimilation process of Vietnamese women, typifying them as loving mothers, good daughters-in-law, and supportive wives. The Vietnamese woman in the film Banga Banga fits into this typified representation of women from Southeast Asia: she is an “good mother” whose “innocence” is protected by the Korean man, Banga.

The ulterior motive to make these women look “innocent” is not innocent at all: the image is an imposition of the socially and institutionally constructed desire to make them comply with the patriarchal social order.

Conclusion

As I have tried to demonstrate, the state’s immigration policy is patriarchal and exclusive that accommodates multicultural families while ignoring migrant workers. Those women who settled into rural areas through marrying Korean men are the main targets of the Korean government’s multicultural policies. As one of the country’s bestselling writers, Pak Pǒmsin, portrays in his recent novel, Namasŭt’e (2005), male migrant workers have far more difficulty obtaining immigrant status through marriage than do female migrant workers. The patriarchal bent of the state’s assimilationist multicultural policy in turn eliminates the possibility for migrant brides and their children to maintain their cultural and political ties to their home countries.

The South Korean government has been actively seeking the transnational political, cultural, and economic involvement of overseas Koreans in their homeland-by giving them voting rights in 2012, for example-while the multicultural policy is oriented around the patriarchal nationalism that exclusively demands migrant women’s full assimilation into Korean society through obtaining cultural knowledge about Korea and adapting themselves into the patriarchal family relations. This double standard will produce negative social effects in the long run, discouraging members of multicultural families from performing active citizenship in Korea.

I examined films that concern the multicultural discourse in Korea as a way to problematize the deeply seated notion of monoethnic and patriarchal nationalism that is manifest in the representation of hypermasculine and emasculated male migrants and domesticated female migrants. Some of these films play a constructive role, by providing an opportunity for Koreans and migrants to respond to the problematic representations of culturally and ethnically different Others; and to enhance mutual understanding between them. Indeed, these films are often discussed and critiqued by Korean citizens and migrants. While government policy lacks inclusive measures, it is noteworthy that the films are expanding the communication space for critiquing the changing social landscape of Korea.

Dr. Jooyeon Rhee is Lecturer at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Her main research examines gender representation in modern Korean literature. Her research interests include Korean film, Korean diaspora and Korea-Japan cultural interactions.

Recommended citation: Jooyeon Rhee, “Gendering Multiculturalism: Representation of Migrant Workers and Foreign Brides in Korean Popular Films”, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 14, Issue 7, No. 9, April 1, 2016.

Bibliography

Films and Literature

Address Unknown. 2001. dir. Kim Kiduk.

Banga Banga. 2010. dir. Yuk Sanghyo.

Namasŭt’e. 2005. Pak Pǒmsin. Seoul: Hangyore ch’ulp’ansa.

New World. 2012. dir. Park Hunjǒng.

The Yellow Sea. 2010. dir. Na Hongjin.

Where is Ronnie… 2009. dir. Sim Sangguk.

Wandŭgi. 2011. dir. Lee Han.

Secondary Sources

Korean Statistical Information Service. www.kosis.kr. Migrant World Film Festival.

Chŏn, Hyŏngbae. 2009. “Oegugin kŭlloja koyong chŏngcha’ek [Employment policies on migrant workers in Korea].” Justice 109: 290–315.

—. 2010. “Oegugin kŭlloja ŭi nodong inkkwŏn [Labour and human rights of migrant workers].” Nodongpŏp nonch’ong 18: 125–57.

Chŏng Sŏnhi. 2014. “Kungnae chunggugin yuhaksaeng ŭi taehak saenghwal silt’ae chosa mit kwalli pangan yŏn’gu [A survey on Chinese students’ living conditions in Korean universities and a study of the management of the students].” Chungguk ŏmun nonyŏk ch’onggan 34: 447–66.

O, Suung. 2010. “Hwanghae: aecssion/ssurillo [Hwanghae: Action/Thriller].” Chosun ilbo, December 23. Accessed July 23, 2015.

Chung, Byong-Ho. 2008. “Between Defector and Migrant: Identities and Strategies of North Koreans in South Korea.” Korean Studies 32: 1–27.

Elfving-Hwang, Joanna. 2013. “Cosmetic Surgery and Embodying the Moral Self in South Korean Popular Makeover Culture.” The Asia-Pacific Journal 11.24(2). Accessed July 20, 2015.

Fattig, Jeoffrey, 2013. “South Korea’s Free Speech Problem.” Accessed April 3, 2014.

Freeman, Caren. 2011. Making and Faking Kinship: Marriage and Labor Migration between China and South Korea. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Haggard, Stephen. 2013. “Peterson Institute for International Economics, Freedom of Expression: South Korean Case Continued.” North Korea: Witness to Transformation, August 27. Accessed April 1, 2014.

Harvey, David. 2007. A Brief History of Neoliberalism. London: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Higham, John. 1993. “Multiculturalism and Universalism: A History and Critique.” American Quarterly 45(3): 195–219.

“Hwanghae kamdok Na Hongjin [The director of Hwanghae, Na Hongjin].” 2010. Kyonghyang Daily, 29 December. Accessed February 16, 2014.

Im, Yangjun. 2012. “Han’guk ijunodonja e taehan sinmun ŭi podo kyŏnghyang kwa insik yŏn’gu [Report patterns on and reception of migrant workers in newspapers].” Ŏllon kwahak yŏn’gu 12(4): 419–56.

Kang, Chinung. 2012. “Diasŭp’ora wa hyŏnjae yŏnbyŏn chosŏnjok ŭi sangsang toen kongdongch’e [Diaspora and the imagined community of the ethnic Koreans in contemporary Yanbian prefecture].” Han’guk sahoehak 46(4): 96–136.

Kim, Hyesun. 2006. “Han’guk ŭi tamunhwa sahoe tamnon kwa kyŏrhon iju yŏsŏng [Multicultural discourses and migrant brides in Korea].” Han’guk sahoehak (special issue): 47–78.

—. 2014. “Kyŏrhon imin yŏsŏng ŭi ihon kwa tamunhwa chŏngch’aek [Divorce of married migrant women and multicultural policy].” Han’guk sahoehak 48 (1): 299–444.

Kim, Hyuk-Rae, and Ingyu Oh. 2011. “Migration and Multiculturalism Contention in East Asia.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 37(10): 1563–81.

Kim, Minjeung. 2014. “Can the Union of Patriarchy and Multiculturalism Work?” In Multiethnic Korea? edited by John Lie, 277–300. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Kim, Sŏnmi. 2011. “‘Han’gukjŏk’ tamunhwa chŏngch’aek kwa tamunhwa kyoyuk ŭi sŏngch’al kwa cheŏn [A ‘Korean style’ multicultural policy and reflection on multicultural education].” Social Studies Education 50(4): 173–90.

Kim, Yŏngŭn, Chŏng Ch’ŏryŏng, and Yi Kŏnnam. 2012. “Tamunhwa kajŏng chanyŏ ŭi chigŏp insik, chillo taean yŏngyŏk mit chigŏp p’obu [Occupational perceptions and zone of accessible alternatives, occupation aspiration of children from multicultural families].” Han’guk silkwakyoyukhoe, 25(4): 169–94.

Kim, Yŏnju. 2012. “Tamunhwa kajŏng chanyŏ 37% ga wangtta [37% of children in multicultural families are bullied].” Chosŏn ilbo, January 10. Accessed May 15, 2015.

Lie, John. 2014. “Introduction: Multiethnic Korea,” in Multiethnic Korea? ed. by John Lie, 1-30. Berkeley, CA: University of California Preaa.

Lim, Timothy. 2014. “Late Migration, Discourse, and the Politics of Multiculturalism in South Korea: A Comparative Perspective.” In Multiethnic Korea? ed. John Lie, 31–57. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Moenig, Udo. 2015. Taekwondo: From a Martial Art to a Martial Sport. New York: Routledge.

No, Sŏnghwa. 2011. “Yŏnghwa ‘Hwanghae pip’an’ [Criticizing The Yellow Sea].” Moyiza. Accessed July 10, 2015.

Parreñas, Rhacel Salazar, and Joon K. Kim. 2011. “Multicultural East-Asia: An Introduction.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 37(10): 1555–61.

Suh, Jae-Jung, Sunwon Park, and Hahn Y. Kim. 2012. “Democratic Consolidation and Its Limits in Korea: Dilemmas of Cooptation,” Asian Survey, 52 (5): 822-844.

Yi, Jasŭmin. 2013. “Taehanminguk och’ŏnmyongi ta tamunhwada [All fifty million Koreans are multicultural].” Dailian, February 10. Accessed April 1, 2014.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Professor Elyssa Faison, Professor Tessa Morris-Suzuki, and Professor Laura Hein for their constructive comments and suggestions that contributed to improve the article. And I would like to thank the Director of The Harry S. Truman Institute for the Advancement for Peace, Professor Menahem Blondheim, for his great support for Korean studies at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Notes

The recent blockbuster was Myŏngnayng (The Admiral: Roaring Currents), a film about General Yi Sunsin and his leadership in naval battles during the Imjin War, which drew more than 1.6 million viewers (Korean Film Council).

Not only was Korea’s free press ranking downgraded from “free” to “partly free” in 2011 (Fattig 2013), but criminal defamation cases have also increased significantly since the arrival of the Lee administration, reaching almost 10,000 cases in 2011 from 4,000 in 2007 (Haggard 2013).

The Korean government initiated its “Study in Korea” project in 2001, and the number of foreign students increased from about 1,600 in 2001 to almost 100,000 in 2012, of which students from China comprise almost half of the total number (Chŏng 2014, 447–66). The total number of foreign visitors to Korea reached almost 1.35 million, out of which two thirds of the visitors were tourists. Tourists from East Asia, South Asia, and Southeast Asia comprise about 84 per cent of the total number of visitors as of May 2015 (Korea Tourism Organization, accessed August 6, 2015).

A further explanation of this pattern is that many men in rural areas have difficulty finding marriage partners, since young Korean women are reluctant to settle into farming households. Due to the shortage of marriageable women, the state and private marriage agencies have provided opportunities for these men to seek foreign wives.

This kind of comparison appears prominently in right-wing newspapers such as Chosŏn ilbo, DongA ilbo, and Kyŏnghyang sinmun.

Koreans and ethnic Koreans share their opinions on this identity issue through a few online communities, such as Moyiza (www.moyiza.com).

Since there are quite a few responses, I will introduce only some of them that discuss these points. Pak Hoyŏl, “Ya han’guk sahoe! Onjekkaji bangabanga halkkonya? [You, Korean society, until when will you say bangabanga?],” Ohmynews, October 1, 2010. Pŏdŭnamu kŭnŭl, “Yŏnghwa Banga Banga ga chunŭn ssŭpssŭlhan mesiji [A bitter message that comes from the film Banga Banga]”. Some of the film critics’ reviews can be found in Cine 21.

This festival was established in 2006 by native Koreans and foreigners in Korea, including migrant workers and multicultural families. The festival is held annually and it encourages the participation of anyone who is interested in making films about the living and working conditions of foreigners in Korea and enhancing communication between migrants and native Koreans. Mahbub Alam, who plays Ronnie in the film, is one of the most representative media activists in trying to improve human rights condition for foreigners in Korea.