The Sewol ferry carrying 476 passengers including a group of high school students on a field trip to Jeju Island capsized on April 16, 2014, and sank to the bottom of the sea off Korea’s southern coast. Most of the crew, including the captain, were rescued by the Korean coast guard. Some of the passengers, who happened to be on the deck or escaped soon after the capsizing, were saved by fishing boats and commercial vessels that came before the ROK Coast Guard or Navy. 304 passengers, however, were trapped inside and drowned.

|

On September 21, Japan’s Fuji TV broadcast a program that reconstructed a heart-wrenching tragedy of the Sewol’s sinking on the basis of survivors’ testimonies and footage from recovered cell phones. One of the survivors states “I hope the coverage [by the Japanese media] helps shed light on why this happened and who was at fault,” alluding to the lack of adequate coverage by the Korean media. |

The ship’s sinking may seem an unfortunate accident, the operation to save the passengers a heroic drama enacted in seas, and the passengers’ death its tragic ending. Once the surface is scratched, however, a complicated picture emerges. The Sewol sank under the weight of the neoliberal state that diminished its role in safety regulation and oversight. The rescue operation was weighed down by an irresponsible state that relegated its responsibility to a private salvage firm. When questions arose about the state’s responsibility, however, it was not shy about mobilizing its resources to evade and deny responsibility. The whole tragedy serves as a reminder of how neoliberal deregulation and privatization puts people’s safety and life at risk through processes of state collusion with business interests and how a powerful national security state may fail to protect its own people from internal dangers it helps create.

The Sewol Sinks under the Weight of the Diminishing State

The ROK Coast Guard concluded on April 17 that an “unreasonably sudden turn” to starboard, made between 8:48 and 8:49AM, was the cause of the capsizing. The Automatic Identification System (AIS) data, that kept the ship’s trajectory until its sinking, seems to confirm the sudden turn. But this raises two other questions.

First, why did the third mate at the helm have to make a turn so sudden and steep as to capsize the ship? At the trial on June 10, the third mate testified that she instructed the quartermaster to turn the ship by five degrees in order to avoid colliding with “a ship” that was approaching. She testified in court that a ship “emerged” from the opposite side and “she was watching the radar and the front while listening to the radio in order to avoid a collision.” Her testimony is corroborated by a video recording by a commercial ship that was passing by the Sewol at the time of the accident: it shows an object moving towards the Sewol. Also, AIS data restored from the Mokpo AIS Station – the Sewol’s own AIS was turned off at 8:48 AM for an unknown reason – shows a trail left by an independent moving object.

Quartermaster Cho stated in a TV interview on April 19 that he turned the helm as ordered by the third mate, but when he did, the ship turned more than usual. When the surviving passengers told reporters that they felt a shock in the front side of the ship, their remark initially prompted speculation that the ship might have hit a reef or rock under water. But when the complete trajectory of the Sewol was released after a long delay, it suggested something different. It showed the ferry not only turned by the five degrees ordered by the third mate, but gradually changed course almost 180 degrees as if it had been pushed by an object traveling with great momentum in the opposite direction.

What caused the Sewol crew to make a sudden turn remains unexplained. What forced the ship to change course and move in the opposite direction from its previous course likewise remains a mystery.

Second, why did the Sewol capsize when it changed course? Investigations revealed that the ship had been modified to accommodate more passengers than would be safe. Added to the overcrowding was cargo overloading. The ship’s operators loaded twice as much as regulations would allow, and apparently did not secure the cargo as per safety guidelines. To accommodate the overweight, the crew removed water from the ballast, creating a perfect condition for capsizing. The ferry had too heavy cargoes that moved around and too many passengers who were told to stay put while too little water remained in the ballast to stabilize the ship.

This raises a host of questions. Why was the Chonghaejin Marine Co., Ltd., the Sewol’s owner, allowed to add more floors than the safety law allowed? How could the operators overload the ship without being caught? How could they remove ballast water to the ship’s peril? Why were none of these violations caught or stopped before the Sewol set sail? These questions lead one to the shadowy relationship between shippers, the shipping industry organization and the regulators – haefia, a Korean syllogism that concatenates hae meaning sea with “fia” from Mafia, “sea Mafia.” It is an iron triangle of the sea that thrives in the age of neoliberalism.

The Sewol had been built and operated in Japan for almost 18 years without any accidents until 2012 when it was retired and sold to Chonghaejin Marine Co., Ltd. that had a monopoly on the lucrative Inchon-Jeju line. The Korean owner bought the ferry which had been retired in Japan after the Lee Myung-Bak administration extended passenger ships’ life from 20 to 30 years by changing the relevant law, thus allowing the Sewol another ten years of life in Korea. The neoliberal administration that vigorously pursued deregulation justified the extension on the ground that it would help the Korean shipping industry save $20 million per year in operating costs and become profitable. It thus unambiguously placed Industry profit before safety and life.

If the Ministry of Land and Sea Management took active steps to deregulate, another wing of the government provided Chonghaejin with the cash needed for it to take advantage of the deregulation. Chonghaejin itself had been established by absorbing Semo Marine Transportation after 200 billion Won (roughly $200 million) of its debt was forgiven. The Korea Development Bank, a wholly state-owned bank that finances major industrial projects, then loaned $10 million, an amount that almost matched the $12 million that Chonghaejin paid for the Sewol. Taking advantage of the deregulation and the government’s generosity, Chonghaejin added two floors in order to maximize the number of passengers it could accommodate. It also expanded the Sewol’s cargo space.

There was still one more obstacle to overcome before Chonghaejin could turn the deregulation and the policy loan into a real profit. It had to pass the safety inspection before it could launch the Sewol, and it passed the inspection without difficulty. While the additions undermined the ship’s stability by adding more weight at the top and thus endangered passengers’ safety, the modification was inspected and approved by inspectors from the Korean Register of Shipping (KRS), a private entity that is responsible for the inspection and registration of ships. Also when it inspected over 200 safety features of the Sewol in February, it approved all with a “satisfactory” rating. Prosecutors, investigating the process of inspection and approval, have discovered that government oversight of the KRS that performs the safety inspection on behalf of the government has been lax. A cause might lie in the fact that government regulators frequently find employment at the KRS after retirement.

Chonghaejin’s greed did not stop there. It took advantage of a loophole in the government’s safety regulations to routinely overload the Sewol. In Korea’s coastal shipping industry, shippers’ safety practices are monitored and inspected by the Korea Shipping Association, an industry organization that represents the interests of about 2,000 members engaged in coastal shipping. In a flagrant case of self-regulation, its headquarters is responsible for “safety guidance” and “implementation of safety measures” while its branch offices are tasked with offering “guidance for passenger ferry’s safe operation” and inspecting the number of passengers and the amount of cargo aboard a ship. The Marine Transportation Law creates the position of the vessel safety operators to guide and oversee the shipping businesses’ safety practices, but the safety operators are employed by the industry organization although their expenses are subsidized by the government. Passenger safety is thus entrusted to the shipping business whose priority probably lies elsewhere.

It took the tragedy of the Sewol for everyone to see that the industry’s self-regulation was a formula for accident. Before the Sewol set sail on April 15th, its operators loaded it with 180 vehicles and 1,157 tons of cargo, but grossly under-reported that it had only 150 vehicles and 657 tons of cargo. To evade inspectors’ eyes, they removed water from the ballast so that the ship would float above the safety line. The overloading in combination with the ballast emptying made the ship prone to capsizing. The Sewol’s regular captain, who had been replaced with a temporary hire for the voyage, testified in court that these were common practices and when he raised the issue with Chongaejin officials, he was told that if he were to raise his voice, he should “resign” from his post. The ship’s overloading and false report were exposed only after the Sewol sank, and it was on June 3rd that the Gwangju District Court issued an arrest warrant for a senior vessel safety operator of the Korea Shipping Association’s Incheon unit for negligence.

The collusion between the state and the Sewol’s owner risked not only the passengers’ safety and life but also the crew’s. Most of the Sewol’s crew consisted of temporary contract workers, a common practice among Korea’s domestic maritime transporters. Lee Junsok, the Sewol’s captain, for example, was a 69 year old temporary hire contracted with a monthly salary of $2,700 a little before the Sewol’s departure. More than half of the crew, including the captain during the fatal voyage, were temporary workers with contracts of 6 months to a year. They were not only denied fringe benefits, but they were also without adequate safety training. As if hiring temporary workers was not enough to trade passengers’ safety for profits, Chonghaejin minimized its spending on crew training. It allocated a paltry $540 for the crew’s safety education in 2013 whereas it spent $10,000 on “entertainment” and $230,000 on PR, clearly showing its priorities. And yet it is this crew that is currently standing trial for the death of the passengers.

|

Most of the Sewol’s crew, including the captain at the time of the accident, were temporary workers with contracts of less than a year. While Chonghaejin spent $540 for the crew’s safety education in 2013, it is this crew that is currently standing trial for the death of the passengers. |

The Sewol sank under the weight of the collusion between the neoliberal state that sheds its responsibility to safeguard people’s lives to private entities and the private entity that trades customers’ safety for profits. The accident serves as a vivid reminder of what tragic consequences can result from government-business collusion. While collusion had existed under previous authoritarian regimes that sometimes sacrificed people’s safety for profits, the Sewol incident reveals that the nature of the collusion shifted to give more power to business interests. The authoritarian developmental state shed some of its power as part of the IMF-imposed structural adjustment after the 1997 financial crisis. As the government transferred some of its power to plan, manage, and oversee the economy to private entities, its relative power gradually declined. By the time of the Sewol disaster, the government took a hands-off approach to overseeing such “private” entities as the KRS. Privatized entities with increasing boldness ignored government directives and warning, and became more independent and aggressive in pushing their agenda.

Rescue Failures of the Disappearing State

One of the greatest mysteries surrounding the Sewol incident is that neither the crew nor the government, including the coast guard and the navy, made serious efforts to rescue the passengers trapped inside the sinking ferry. Thirty five passengers were picked up from the deck and airlifted by three coast guard helicopters. Most of the crew, including the captain, was rescued by the coast guard’s patrol boat 123 that pulled up to the control room of the Sewol so they could jump to safety. The patrol boat returned later to rescue additional passengers. Most of the surviving passengers were saved because they jumped off the ship before it submerged and were pulled out of the water by fishing boats that happened to be nearby. Other than these, no one was rescued from the sinking ship by the coast guard or the navy after about 10:25.

The next several hours, the “golden time” in which the passengers could have been saved, was notable for the absence of active rescue operations. The Navy’s Ship Salvage Unit (SSU) and Underwater Demolition Teams (UDT) as well as the Coast Guard’s special units were dispatched, but arrived late and did not engage in active rescue operations. Their failure was compounded by deadly instructions by the crew which repeatedly broadcast instructions to the passengers to stay put and not leave the sinking ship, contrary to common sense. In another illogical instruction, they told the passengers to wear life jackets first and stay within their cabin. The instruction proved deadly when the ship capsized and the passengers were trapped underwater, for, wearing a personal floating device, they could not swim underwater to escape from their cabins. A majority of the passengers, high school students, followed the crew’s direction to their detriment. Meanwhile, the crew, including the captain, was among the first to abandon the ship, leaving behind over 300 passengers waiting in their cabins as they were told.

The crew’s failure was compounded by the coast guard. The coast guard dispatched patrol boat 123 to the Sewol, and although some members of the coast guard boarded the Sewol before it sank, they made no effort to rescue the remaining passengers or even to tell them to abandon the ship. They limited themselves to rescuing the Sewol’s crew. The captain of patrol boat 123 testified in court on August 13 that he “panicked so much that he forgot” to instruct his crew to move into the Sewol’s cabins, adding that he was “so busy that he could not tell the passengers to evacuate the ship.” Commissioner of the Coast Guard, Kim Sok-Kyun, did not do much better. He instructed, via the West Sea Coast Guard Task Force, patrol boat 123 to send its crew to the Sewol and “calm the passengers to prevent them from panicking.” What is clear is that no order was issued from the top of the coast guard hierarchy to rescue the passengers before the ship sank. Video footage of the Sewol during the golden time shows coast guard boats circling around the slowly submerging ferry, effectively keeping away the fishing boats that had come to help save the passengers.

|

Newstapa, a trailblazer of Korea’s investigative journalism, aired a program that exposed the absence of the state during the “golden hours.” |

It was not just the fishing boats that were kept away. The navy could not enter the scene of the accident to participate in the rescue operation for the first two days. In the meantime, Undine Marine Industries, an ocean engineering firm that specialized in offshore construction and marine salvage but that had no record of, or professional employees trained for, passenger rescue, emerged as the central rescue operator. The day after the accident, Undine was contracted by Chonghaejin at the recommendation of the Coast Guard, and took control of the rescue operations, sidelining rescuers from the coast guard and the navy. The problem is that it acted as if it was more interested in salvaging the ship than saving the passengers’ lives. Indeed, its divers saved not a single passenger. Even when all the passengers remaining in the ship were presumed dead, it delayed retrieving the bodies of the dead for as long as 20 hours. The void left by the state was filled by a private company that may have sought to maximize its profits by extending its operations as long as possible.

The state as an organization whose fundamental mission is to protect the people’s lives and provide for their safety failed throughout the crisis. Not only did it fail to establish an effective control center that would mobilize national resources necessary for rescue operations, but it added to the chaos of the accident by creating obstacles to the rescue and spreading faulty information. Various units of the government created a total of ten headquarters in response to the Sewol’s sinking, creating confusion as to the line of command and producing problems in communication among government units. Ministries of Security and Public Administration, Oceans and Fisheries, and Education, administration, set up their respective headquarters while the Coast Guard and Kyongki Provincial Government also created theirs. During the critical initial hours, not only was the central coordination of rescue operations lacking but no credible information was available. Different entities reported different numbers of rescued passengers, and in what proved a fatal mistake, the Central Disaster Management Headquarters announced that 368 passengers were rescued at 1:19PM, 4 hours after the ferry’s sinking, when in fact over 300 of them were missing. It was only the day after the accident that all the involved government units agreed to establish the Pan-Government Accident Response Headquarters that unified the rescue operations and communication. By then, the “golden time” was over, and the remaining passengers were presumably dead.

The irony of ironies is that the potent power of the military deployed to save civilians was stopped by the weaker coast guard to create room for a private salvage company to operate. The Tongyoung, the state-of-the-art salvage ship recently acquired by the navy, was ordered by Hwang Ki-Chol, Naval Chief of Operations, twice to sail to the scene of the accident and help the rescue operation, but it never left its port. Representative Kim Kwang-Jin suggested that “it was difficult to understand why the Tongyoung was not dispatched even if the naval chief of operations twice ordered emergency assistance.” Kim Min-Sok, the Ministry of National Defense spokesperson, responded that it could not participate in the rescue operation because one of its critical components, a rescue submarine that was needed to retrieve passengers from the sunken Sewol, had not been sufficiently tested or certified for operation. Why then did the top naval commander make an uninformed order that the uncertified ship participate in the rescue? Who made the decision to effectively disobey the Naval Chief’s order? Why was no one reprimanded for such a fatal snafu? All of these unanswered questions have led to speculation that a higher authority, one higher than the Naval Chief, played a role.

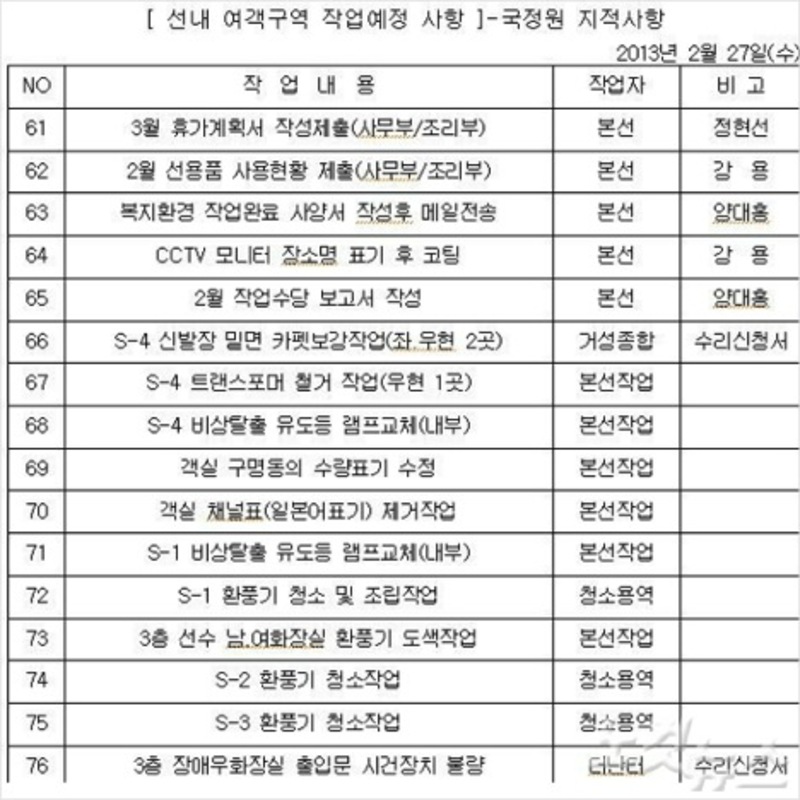

Many suspicious eyes turned toward the National Intelligence Service (NIS) for Nam Jae-Joon, its chief, is known to be one of the president’s confidantes and wielded more power than his official position might suggest. Two documents, retrieved from the Sewol, seem to indicate that the NIS had been deeply involved in the operation and management of the Sewol. First, the Sewol’s emergency contact diagram lists the NIS as the first point of contact in case of accident. It and its sister ship, the Ohamana, also owned by Chonghaejin, were the only ones among the 17 large passenger ferries that were required to report an accident to the NIS before any other agency such as the coast guard. Second, a laptop computer retrieved from the sunken Sewol had a document, titled “Items of Planned Work in the Ship’s Passenger Area – List of Items Identified by the NIS,” that listed 100 items that the National Intelligence Service (NIS) ordered repaired. Although the NIS later claimed that it ordered those repairs for security purposes, the list included such items as vending machine installation, recycling bin location, ceiling paint, ventilator clean-up, etc. to which a security agency would not normally pay attention unless it was involved in managing the ship. According to the list, the NIS even required the Sewol to submit an employee wage report and the crew’s vacation plan as if it had been involved in operating the ferry. These documents fueled suspicions that the NIS, as the real owner of the Sewol, was implicated in foul play.

|

A laptop computer retrieved from the sunken Sewol contained a document, titled “Items of Planned Work in the Ship’s Passenger Area – List of Items Identified by the NIS,” which listed 100 items that the National Intelligence Service (NIS) had ordered repaired. This document, together with another, fueled suspicions that the NIS might have been the real owner of the Sewol. |

Why would the intelligence agency sacrifice a ship? Pointing to the fact that the NIS had been on the hot seat before the Sewol disaster, critics raised the suspicion that it needed a scapegoat to divert attention. The NIS had indeed been struggling to defend itself against mounting evidence that it had been deeply implicated in a fabricated spy incident. Yoo Woo-Sung, a Chinese Korean who had defected from North Korea to the South, was accused by the NIS of working as a North Korean agent after his defection. He responded by accusing the NIS of falsely charging him. It was discovered during a court trial that NIS officials had used pressure and inhumane treatment to force Mr. Yoo’s sister to testify against him and some NIS officials had gone so far as to forge three Chinese official documents to present to the court as evidence. In response to a query by a defense lawyer, the Chinese Embassy relayed to the court an official statement that the said documents were not authentic, creating a diplomatic fiasco. Added to the mounting evidence that the NIS had been involved in the last presidential election and other domestic politics, the spy fabrication case could become the last straw for the NIS leadership. Public outcry was so strong and grew so rapidly that on April 15th Nam Jae-Joon, Director of the NIS, had to make a public apology for the spy fabrication although he also made clear his intent to stay on the job.

The day after his press conference, the Sewol sank. The accident diverted attention from the NIS scandal. But the diversion did not last long as evidences of the NIS’s implication began to emerge. The Sewol’s emergency manual and repair work list, unexpectedly discovered, fueled suspicions about the NIS’s role and as the media and the opposition parties focused attention on this. As public suspicions grew, Nam Jae-Joon, the intelligence chief, tendered his resignation on May 22nd, and President Park swiftly accepted it. Because neither he nor she offered a compelling reason, the Lawyers Alliance for Democracy pointed out in a statement that there was ground to suspect that NIS had been implicated in the Sewol’s sinking and the failed rescue operation. Nam’s resignation nonetheless helped shield the ruling Saenuri Party from political liability just 10 days before a local election. It also protected the intelligence agency from parliamentary inspection, for the top intelligence officer who was in charge of the agency at the time of the accident was no longer available to report to the Parliament’s special committee on the Sewol.

Thus the parliamentary special committee called on Chief of Staff Kim Ki-Choon, who is commonly viewed as the real power in the presidential office, to testify on the Sewol. While evading most questions and doing his best to clear the Blue House of any responsibility for the bungled rescue, he nonetheless revealed an important fact in response to questions about the president’s whereabouts during the golden hours. He testified that he and other officials reported to the president via written reports or telephone calls but there were no face-to-face meetings until President Park showed up in the Central Disaster Management Headquarters around 5PM. Her appearance there after seven hours of missing in action was nationally televised. So was her ignorant question: “if the passengers are wearing a life vest, why is it so hard to find them?” Apparently she was unaware that they were trapped inside the overturned and submerged ship and thus could not be seen in the open sea. The President’s daily log, later released via Representative Cho Won-Jin of the ruling party to quell questions about her whereabouts, only confirmed her absence, for it failed to list a single face-to-face meeting. What had she been doing for the seven hours? Where was she?

|

President Park Geun-Hye appeared at the Central Disaster Management Headquarters around 5PM, after 7 hours of absence that has never been accounted for, and asked an ignorant question: “if the passengers are wearing life vests, why is it so hard to find them?” Apparently she was unaware until then that they were trapped inside the overturned and submerged ship and thus could not be seen in the open sea. |

Wherever President Park may have been on April 16th, it is more than clear that the state, from top to bottom, was absent from rescue operations during the golden hours when the passengers could have been rescued. What looked like a strong national security state failed to save people’s lives from the danger it had created with deregulation and privatization. The Korean state proved a failed one when it came to saving people’s lives from a disaster it had helped create.

The Families Demand Truth and the State Evades

The Sewol tragedy resulted from the collusion of Korea’s sea mafia, neoliberal deregulation run amok, the intelligence agency involved in shadowy activities, and a president possibly distracted by her private life. This would make a good movie, except that it cost the lives of 324 people, mostly high school students leaving their surviving parents and relatives still grieving and searching for the truth. One of them staged a hunger strike for 46 days to demand an independent and exhaustive investigation. The victims’ families demanded that a special law be instituted to create an independent committee with subpoena and prosecutorial powers in order to find the causes of the death of their beloved ones. They believe that creating an independent committee is critical to finding an answer to questions about the Sewol’s sinking and the government’s failure to rescue, because all other methods have proved abortive.

|

The victims’ families have been praying, literally, that a special law be instituted in order to unearth the truth about the Sewol tragedy, only to be blocked by the police. President Park has thus far rejected their plea. |

The national parliament on May 29 created a special committee to investigate the Sewol accident, but the committee proved dysfunctional from the beginning. Its operation was stymied by repeated clashes over what to do between the two main political parties, the conservative Saenuri Party and the liberal Democratic Alliance for New Politics. Furthermore, the ministries and agencies, called to report to the special committee, dragged their feet and revealed little that was new. The Blue House made an effective investigation difficult by releasing only 13 of the 269 materials requested by liberal members of the committee two days before it was due to testify. The committee ended its work without even holding a hearing. The special committee failed to bring out the truth, as the Sewol victims’ families committee noted.

The Board of Audit and Inspection (BAI), Korea’s counterpart to the U.S. Government Accountability Office (except that it is part of the executive branch of the Korean government) conducted its own investigation. After auditing the Blue House, it concluded that the presidential office was not responsible for the Sewol failure. The sole basis for its conclusion seemed to be a Blue House statement that “the Blue House is not the control tower of disaster management.” It turned out that the BAI sent a few low-ranking officials to audit the Blue House, and they completed their work without even examining the reports that had been submitted to the president on the day of the accident.

Prosecutors and the police have produced more questions than answers. Prosecutors have been more aggressive in pursuing Yoo Byung-Un and his family for bearing the ultimate responsibility as the real owners of Chonghaejin than in investigating the government’s failure to rescue the passengers. Even their investigative work on Mr. Yoo has been shoddy. They staged a nationwide manhunt to arrest him, even to the point of organizing neighborhood watch meetings throughout the country for the first time since 1996, but missed him in a search of a house where he was hiding, only to identify a dead body, as his, 40 days after the body was discovered. Not to be outdone, the police sent the Sewol’s captain, Lee, to the apartment of one of its officers’ for the night after the Sewol’s sinking, and provided him with a safe haven for almost a day. Prosecutors have thus far indicted some of the crew and lower ranking officials for various charges related to the Sewol’s sinking, but have turned a blind eye to the rescue failure.

Their failure to bring out the truth was accompanied by efforts by the National Intelligence Service (NIS) and the police to silence the victims’ families and their supporters. The police had monitored the victims’ families when they held meetings and blocked them when they tried to reach the Blue House to make a direct appeal to the president. The riot police isolated the families and their supporters by surrounding them with a wall of police buses. An unidentified person reportedly snooped around the hometown of a victim’s father in what looked like a fishing expedition. An NIS agent paid a visit to the hospital that employed a doctor who was helping the victims’ families, and met with its director to inquire about the doctor’s background. An SNS and media offensive spread negative rumors about the families. Representative Min Byung-Du alleged that “the rumors are being spread through specific channels created by an expansion and reorganization of what looks like the ruling group’s psychological warfare unit that operated during the last presidential election campaign.”

The Sewol Families Committee sent a letter to President Park on August 22. In it, the families pointed out that “there is a larger issue at stake than specific issues related to a special law” and “that is whether the truth will be revealed or hidden.”

“We have come to know that at the center of the efforts to hide the truth stands the Blue House,” the families wrote. ”The president said that the truth must be unearthed lest the families should have any remorse, but has even refused to submit materials to the audit by the parliament.” The victims’ families demand that a special law be instituted to create an independent committee with subpoena and prosecutorial powers in order to find the causes of the death of their beloved ones. They believe that creating an independent committee is critical to finding an answer to questions about the Sewol’s sinking and the government’s failure to rescue. Kim Young-O, father of one of the victims, even staged a hunger strike for 46 days to demand just that.

The Park administration and the ruling Saenuri Party thus far have refused to heed their demand for truth. What are they afraid of?

Jae-Jung Suh is an Asia-Pacific Journal associate and the author of Power, Interest and Identity in Military Alliances. He may be reached by email.

Recommended citation: Jae-Jung Suh, “The Failure of the South Korean National Security State: The Sewol Tragedy in the Age of Neoliberalism,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 12, Issue 40, No. 1, October 6, 2014.