The Asia-Pacific Journal presents excerpts from Sarah Bird’s newly published novel, Above the East China Sea together with her conversation with Steve Rabson, who served in the army on Okinawa in 1968 en route to becoming a leading translator of Okinawan literature. Bird’s novel engages the theme of suicide and death from the Battle of Okinawa to the present, interweaving the fate of Okinawans and American occupying forces. As Robert Leleux observed in a review of the novel, “In the heightened metaphysical reality of Bird’s novel, humans and ghosts walk among each other, and mortality proves no hindrance to resolving family dramas. In fact, Okinawans’ relationship to death, at least as presented by Bird, seems somewhat offhand, as though the great cosmic divide is actually a very thin veil between our world and the next . . . reminiscent of Faulkner’s great line, ‘The past is never dead. It’s not even past.’” This issue of APJ couples the novel with the recollections of compulsory mass suicide in the Battle of Okinawa in which 16-year old Kinjo Shigeaki killed his mother and two younger siblings.

|

Chapter One

The choking black smoke from the fires raging below rises up, trying to claim me and my child. I climb higher. I must hurry. I must do what has to be done before the sun rises. The black stone of the cliff tears at my skin. I ignore the cuts and drag us up and onto the top.

At the summit, I rise on trembling legs. The hundred thousand spirits who’ve gone before greet us with cries of joy, happy as a flock of crows at sunset hailing the returned. I see them floating all around. I see the women, the young girls, their kimonos fluttering above their heads like tattered banners as they plummet through the air. I see the emperor’s soldiers, emaciated young men, caps flying straight up off their heads as they hurtle down, toward the sea.

They had no choice but to jump. And, now, we have none. The soldiers, either Japanese or American, will kill us as soon as the sun rises. We cannot die such a violent death. If we do, we will be condemned to haunt this place forever and never be reunited with our clan. I won’t permit my child to endure such a cruel fate.

Though night still covers the carnage, I don’t need to see the black of charred ruins or the dun of mud mixed with corpses, which is all that remains of my mutilated island. A breeze from the East China Sea lifts sweat-dampened hair from the back of my neck. It carries with it the stench of death from a place where not a single leaf of green hope has survived.

I close my eyes and remember Okinawa as it was on the day before everything changed. I see the colors of paradise. The pink of the baby piglets. The gold of the trunks of our bamboo grove. The purple of my mother’s sweet potatoes. The yellow of the flowers on the sea hibiscus hedge that lined the path leading to our house. The red of the blossoms on the deigo tree, blazing as though the side of the mountain were on fire. The colors sparkle against a background of infinite green. Leaf, vine, grass. Above and below are blue. The ocean is the blue of jewels. The sky is the blue of softness. All I can give my unborn child now is the blue of sky, the blue of a water death. I hope that I am carrying a son. Life is too hard for a daughter. A sister. A mother. Death will be even harder.

The stones I fill the leather satchel strapped across my chest with are so heavy I can barely stagger forward to the edge of the cliff. But they have to weigh enough to pull us down under the sea and keep us there. We can’t join the hundreds of other suicides who have washed ashore, their corpses swelling even now on the beach far below. My child and I must sleep beneath the waves until the moment chosen by the kami arrives. That is the obligation I must fulfill.

My toes, the soles of my broad, sturdy Okinawan feet, grip the black rock. They cling like dumb animals to life even when only death remains. They beg, saying “Tamiko, please, Tamiko, our fifteen short years on this earth have not been enough.” My feet want to run again through the grass. They want to dance with such grace that I win the love of a handsome boy. They want to carry me home to my mother. To my sister, my Hatsuko.

Though I thought my heart had hardened to a rock, it aches now with missing my family, Hatsuko most of all. I shake away such weakness. I am fifteen. Old enough to know that a mother does what she must for her child in this life and, more important, in the next. I pray to our ancestors, to all the kami-sama. To the ones who’ve gone before, to the gods of hearth and field, altar and forest, to all the spirits who control our destinies. I beg them to help us, to let my child and me enter the next world and be reunited with my family. With our family.

I wrap my arms tight around my belly and step off the cliff. It is easy. The easiest thing I’ve had to do since the Americans invaded. The kami cradle us, just as I cradle my child. Still, when we land, the sea is hard as concrete. The salt water floods my mouth, throat, lungs. There is a moment of pain, of clawing struggle when I am certain I’ve made a terrible mistake. Then it vanishes and I let the stones drag us down, farther and farther under the waves, until the new-risen sun far overhead shrinks away to a pearl that shimmers briefly before it is lost forever in darkness.

Our wait begins.

Chapter Two

Jump? Or don’t jump?

The question rattles around inside in my head like a handful of BBs in a metal coffee can. Versions of it have been clanging around in there for the past three months, ever since I found out about Codie: Take the pills? Don’t take the pills? Run the exhaust hose in through the car window? Kick back with a bottle of Percocet, a few beers, and watch as many episodes of True Blood as it takes?

I go back and forth. Good days. Bad days. This past week, since my mom’s been gone on TDY, has been good. It’s always easier when she’s not around. Actually, they say that most suicides happen when the person is feeling better. I believe it. When you can’t drag yourself out of bed, it’s hard to get up the energy to even stick a fork in a wall socket. Mom’s temporary duty assignment is over in two days. That gives me forty-eight hours to make up my mind.

A hundred and fifty feet straight down, at the base of the cliffs I’m standing on top of, the waves churn white against some spiked rocks stabbing up above the water. That’s where I’d land. Death would be instantaneous. That’s a plus. Put that one in the “pro” column.

I hold my arms out and a muggy breeze off the East China Sea lofts the hair up off the back of my sweaty neck. In spite of the steam-bath humidity, I still feel like a dried-up leaf, all withered and brown from not being attached to anything, anywhere, in such a long time. It seems like the slightest gust of wind should be enough to blow me off this cliff and out of this life forever. I wish it would.

I’m terminally sick of not being able to decide. Of being trapped in this cycle of what my mom would call “fiddle-fucking around.” Indecision is something they cut out of her in NCO Leadership School. They recently changed the name to the Warrior Leader Course. My mom, though, she never needed a title to tell her what to become. “Shit or get off the pot” has always been her mantra. That and “Get ’er done.” She regularly surprises people because she sounds so country but looks so Asian. She’s half Okinawan which is why I stupidly thought that transferring here would be like returning to some magical ancestral homeland where we would instantly be treated like family. Didn’t quite turn out that way. To say the least.

I experiment with tipping forward. My weight shifts onto the balls of my feet, and my stomach drops worse than if I’d already taken the leap and landed hard. That’s part of the test. Maybe if I push myself this close to the edge, I’ll smoke out a deeply hidden reason for going on living. And maybe psychedelic rainbows and sparkling unicorns will fly out of my ass and I’ll love life again. I’d be open to that.

I am tilting forward, about to let gravity take me, when two ropy arms clamp onto me from behind.

“Hey, Luz.” Kirby Kernshaw’s greeting is an air-rifle puff of beer breath against my neck. “Whatcha doin’, Tiger Woods?”

I open my eyes. Clouds again cover the moon. I inhale once, twice, and shift from being a body on the spiked rocks far below back to being Luz James, new girl at a new base, hanging out with her latest group of Quasis, the semistranger, friendesque beings that I meet at a new assignment, then just about, almost, but not quite, get to know right before we’re transferred again.

“Tiger Woods, where you been, girl?”

“Hey, Lucky Charms.”

Kirby is Lucky Charms for his red hair. A tall, lanky demented leprechaun of a lad who’s been held back at school a few times, Kirby Kernshaw, is one of those gingers whose freckles blend into his lips. I’m Tiger Woods, since it’s easy shorthand for “part Okinawan–part Filipina–part Missouri redneck–part miscellaneous.” You know, your basic caramel person. “Uh, Kirby, you want to stop grinding your stiffy into my butt?”

He laughs, but doesn’t turn me loose.

“Kirbs, for serious, get your hand off my boob.” He removes it. “And the one on my crotch?”

Lucky Charms isn’t so much saving as humping me. He lets go and lurches away, muttering, “Girl, how can someone so hot be so cold.”

Kirby grabs the handles of the red-and-white Igloo cooler beside him, hoists it up, then leans back with the weight braced against his thighs. “A little help, girlfriend.”

“Sure.”

I grip the rear handle of the heavy cooler with both hands, and Kirby leads me down the series of switchbacks zigzagging across the steep face of the cliffs that ring the shore. Bottles and ice clank from side to side as we inch our way along the ant trail. I’ve still got two days left. That’s plenty of time to “get ’er done” before Mom gets back. Okinawa, with its riptides and venomous habu vipers, unexploded ordnance left over from World War II and pill-happy base doctors, is one giant suicide op waiting to happen.

It’s important to me not to seem suicidal. When Family Advocacy investigates after I do it and they ask the Quasis, “How did Luz James seem to you?” I can’t have any of them talking about what a droopy-assed loser I was. I want them to say, “Luz? Luz James? No, she seemed perfectly fine.” Maybe add, “She was always so full of life,” and pretend to be all broken up. The girls especially, even the ones who didn’t know me at all, since that will give them a good reason to cry and show how sensitive they are.

“Hey, Tiger Woods?” Kirby grunts back at me. “Why are you so late? It’s after twenty hundred hours.”

“If you mean eight o’clock, Kirby, say eight o’clock.”

“You’re such a civilian, Luz.”

“Only a Gung Ho would even think that that’s an insult.”

“You callin’ me a gun ho?”

I start to tell him about how Codie called the freaks who were genetically engineered to be military brats Gung Hos. I see her doing her imitation of a typical Gung Ho, jumping around all excited, going, “I love moving! It gives me a chance to reinvent myself!” like they’re Lady Gaga with the whole world just waiting to see the latest incarnation. After a lifetime of our mom and the U.S. Air Force uprooting us every other year or so, Codie and I were so anti–Gung Ho that we even developed mental blocks about decoding the twenty-four-hour clock. It meant that we occasionally committed the worst brat sin of all: being late. But to us, being late was a lot better than being a Gung Ho.

I’m doing it again. I’m relating everything back to Codie.

“Loozer,” Kirby repeats, “why’d you call me a gun ho?”

“Never mind, Kirbs. It’s nothing.” Suddenly very, very tired, I dump my end of the cooler down onto the trail. “Brew thirty,” I say, popping the cooler open. I ice-fish for a beer, hook a tall silver one, and reel it in. The cold feels good against my hot hand, lips, going down my throat. My thirst leaves, but not what I didn’t want to think about: Codie was not a Gung Ho. She wasn’t. That’s why it doesn’t make sense. Why what happened could never have happened.

Chapter Three

Mother, Are you there?

Of course, where else would I be?

Mother, while we wait to be found, tell me once more everything you know about the next world.

I had already told my son everything that his grandmother had told me: that in that other realm the air shimmered like lapis lazuli and was perfumed by the scent of lilies and pineapples. That we would feast and dance beneath the vast roof of a banyan tree. That the timid dwarf deer, the emerald frog, the long-haired mouse, and the orchid leaf butterfly would all emerge from hiding to marvel at the beauty of our arm movements. That we would be reunited with our mothers, fathers, aunts, uncles, grandparents, and great-grandparents beyond remembering.

It galls me that I can do nothing to rescue us from this netherworld and send us on to the shimmering place. Until I join my ancestors, I’m not kami-sama like them, so I don’t have the power to inflict suffering on the living to remind them of their obligations to us. I ache with a ferocity unknown to the living for what was promised in my mother’s stories. For sweet potatoes in green-tea sauce, the scent of lilies and pineapples.

Near the end, when thirst and hunger were knives twisting ceaselessly within us, I believed that my ruined body was the cause of all my suffering. Here I have learned that pain is not sharpened by flesh; it is blunted. With no body there is no way to partition off suffering. It is a curse, yet it gives me an advantage over any of the living, who never see clearly until their eyes are closed forever. They are blind to the injustice of love withheld from the unlovely and lavished on the lovely, who, with their consolations of lovely, long necks and shiny, straight hair, need it so much less. They don’t see how their foolish desires drive them to crawl over one another like crabs in a bucket fighting for a small circle of blue when the whole sky waits above.

And now, though I don’t yet know why the kami have awoken us, I must make myself ready to use my advantage. I concentrate. I put doubt and despair aside and hone my desire. I fletch it like a samurai’s arrowhead. I pull it back taut in the bow until it quivers, and I wait. The rules of destiny are harsh, but to save my child’s soul, I have accepted them. The kami-sama will send to us someone who hovers between the living and the dead. And when that person arrives, I shall be ready and will release the arrow of my yearning straight into his heart.

Okinawa, Life and Death in Two Wars and Two Novels

Novelist Sarah Bird in Conversation with Steve Rabson

Sarah: It’s an honor for me to have this conversation with you Steve. I came to revere your work during the years I spent researching this novel. When I began writing I remember so clearly my trepidation and the constant thought, “What will Steve Rabson think?” That is why it was the greatest of unexpected gifts when you got in touch with me about my novel Yokota Officers Club. That emboldened me to ask if you would read the manuscript of Above the East China Sea. Which you did and offered a wealth of invaluable comments and corrections that saved me, time and again, from embarrassing myself.

Steve: Your kind words are appreciated, but somewhat embarrassing for me since what I do—translations and research—is based on the work of Okinawans. Tell us some of your impressions of Okinawa from the time you were there as an Air Force daughter.

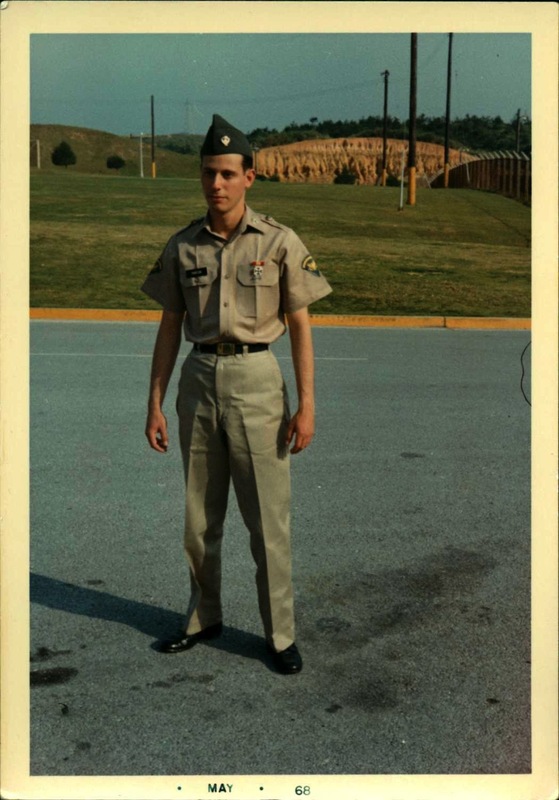

Steve Rabson, Henoko, Okinawa, May 1968 |

Sarah: I arrived in May 1968 after my first year at the University of New Mexico. I had participated in anti-war marches and rallies while in high school, but at UNM I started a group called Damsels in Dissent. Basically, we counseled terrified potential inductees to visit sympathetic psychiatrists who would tell their draft boards that they were crazy; to swallow balls of tin foil that would show up as suspicious spots on x-rays; to put a bar of lye soap under their armpit to raise their temperatures. And, if all else failed, to shoot off a toe or flee to Canada.

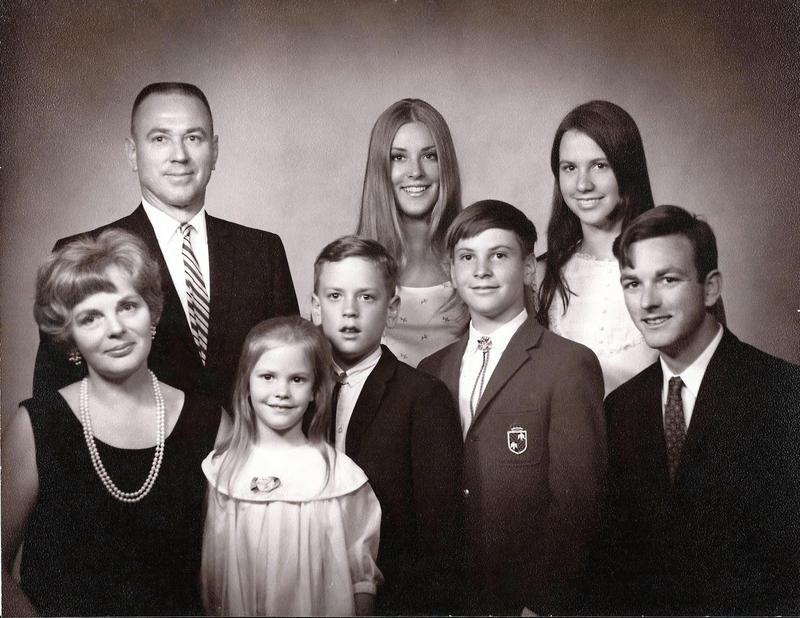

So, when I arrived at Kadena Air Base, my family beheld the girl they’d left behind wearing Weejun loafers and Villager skirt and sweater sets transformed into a hippie with Trotsky glasses and smelling of patchouli oil. And though the oppressively military atmosphere of an overseas American base made me feel as if I’d been dropped behind enemy lines, this was what I knew, what I’d grown up with, and I was also completely, happily, at home once again.

Luckily, my mom was far from a typical officer’s wife. She’d met my father during World War II at a barn dance in north Africa where she was a nurse by day and a singer with a band by night. After having lived a very large life, she found playing bridge and pouring tea at receptions for the commander’s wife stifling. She loved to load her children into the mustard yellow station wagon my parents had bought at the base “lemon lot,” and head out for destinations unknown. We visited the ruins of every castle on the island; hiked up mountain paths that seemed impossibly steep and slippery to us while Okinawan grandmothers in flip-flops scampered past; shopped in Naha department stores; bought scarlet red slices of tuna from stalls in what was then Koza and is now Okinawa City; watched “Elvira Madigan” with English sub-titles; and, thanks to my mother’s curiosity and gregariousness made Okinawan friends wherever we went. On my own, I learned to scuba dive from a way-too-gung-ho Marine who had his dependent students doing free ascensions from ridiculously dangerous depths and discovered the dazzling world under Okinawa’s seas.

Military kids growing up within fenced compounds entirely populated by their own kind, accept more than most children the world they are given by those they love most. So, although I fell in love with both the physical beauty of Okinawa and the other islands we visited, as well as with her vibrant, kind, and joy-filled people, and was a budding radical to boot, I was decades away from questioning our presence on Okinawa.

Steve: You have written two novels set in Okinawa, The Yokota Officers Club and Above the East China Sea. Can you tell us what inspired you to write each of them, and how they drew on your experiences and observations?

Sarah: “Yokota” started off as a frothy look at my two weeks in show business. While visiting Okinawa there was a dance contest. Since the prize was an all-expense paid trip to Tokyo, I entered. Due to my remarkable ability to be both Caucasian and of legal age, I won. The catch was that I was the intermission act for a comedian, Bobby Monahan, during his tours of all the military clubs in the Tokyo area. Thankfully, the novel evolved and ended up being about two things I care vastly more about than go-go dancing: my family and the effect of the U.S. military on the lives of women.

Bird family portrait 1967. The author is top center. |

Two experiences inspired “Above the East China Sea.” One was strolling at night through the vast green swath of the Kadena golf course, looking out through the barbed wire fence at the claustrophobically crowded world beyond, and wondering “Why?” The other was standing at the top of Suicide Cliff and being overwhelmed by sensory impressions—a salt-scented breeze off the East China Sea lifting the hair off the back of my sweaty neck; the infinity of blues as aqua tidal pools darkened to cobalt at the horizon then lightened to a sky blue as pale as skim milk; the dense, jungle smell tinged with the fragrance of honeysuckle rising from the lush vegetation—and again the question, “Why? Why would anyone choose to leave such a paradise?”

Like most young people, I was an unmanned drone flying through my life, gathering intelligence I would make sense of only in later years, when the frenzy of work and raising children and raising myself had subsided. I had started this process while researching Yokota Officers Club, but as I sought to understand Okinawa’s tragic, majestic history I became utterly obsessed. Though astonishments waited on every page I turned, the revelation that haunted me the most was learning about the Princess Lily Girls. I was stunned that such a magnificent tale of heroism, endurance, and nobility could be so little known in this country, and I felt an obligation to rescue it, and the story of the Okinawan people, from obscurity.

Steve: Why did you choose the last name “Furusato” for one of your characters?

Sarah: Oh, you caught that. Very good. As you know the word means “hometown,” but comes with an abundance of connotations, including a yearning, a homesickness, for what has been lost. Loss is a theme that resonates throughout the novel. Both my lead characters are mourning the loss of homes they once knew, and the beloved older sisters who embodied the safety and comfort of hometowns. Abrupt departures are almost the only constant in a military brat’s life, and many are in a constant, unspoken state of mourning for whatever semblance of a “hometown” they’d been able to form before being uprooted again. For Okinawans who’ve been displaced by military bases, there is the additional, indescribable pain of seeing your furusato, your home village, on the other side of a fence, replaced by a runway or a golf course, there within your sight, but gone from you forever.

One other play on a Japanese word: I named my Okinawan protagonist’s furusato, her actual home village, Māda dayo, from the title of the Kurosawa film wherein his lead character repeatedly proclaims “māda dayo!,” “not yet!” to death. So that was my tiny homage to the master’s treatment of eternity and afterlife.

Sarah: The military brought both of us to Okinawa during the Vietnam War years. I as a brat with my Air Force family. You as an Army draftee. Tell me about who you were then and how you ended up becoming a soldier.

Steve: After graduating college in 1965 I volunteered for a draft physical, intending to join the reserves and become a “week-end warrior.” I had a heart murmur and was told I was disqualified. But just a few months later I suddenly received the “greeting” letter with an induction date 21 days later. I appealed, and was given another physical which I passed with flying colors, so to speak. At this point the big escalation in Vietnam hadn’t happened yet, and my friends from high school who’d been drafted were going to places like West Germany, England, and Spain, or staying in the U.S. As a middle-class Jewish boy whose older male relatives had all served in World Ware II, dodging the draft was a kind of “no-no.” I ended up in Okinawa for one year with a thirty-day leave in Tokyo.

Sarah: I came to a deeper understanding and profound appreciation for Okinawa and her people only in my later years as I’ve sought to make sense of my time as a member of the American raj. And to answer questions like, “Why, on our side of the barbed wire fence, were there tundras of open space—golf course, runways, parade grounds, parking lots—while on the other side everyone was claustrophobically crowded together?” Steve, I’m curious about what sparked your fascination with Okinawa and led you to a lifetime of service to the Okinawan people through your work in teaching, translation, literature, and editing?

Steve: Like you I arrived in Okinawa “on our side of the barbed wire fence.” But, like some of the other soldiers at the 137th Ordnance Company in Henoko, I was soon eager to escape the base and travel beyond the nearby “vil’,” a base town in both senses of the word. It was my first time in an Asian country, and the lush, sub-tropical scenery and distinct culture of Okinawa deeply impressed me. I took long walks in the countryside, ate and drank at local restaurants, and heard Okinawan folk music performances at festivals and concerts.

Sarah: My learning curve about the Ryukyu Islands was marked by a series of shocks as I wondered, “How did I not know that more people—mainly Okinawans and Japanese, but also the largest number of Americans in any battle in the Pacific War, as well as Koreans, Taiwanese and others—had died during the invasion than were killed at Hiroshima and Nagasaki combined?” “How was I not aware of the profoundly exploitative nature of our relationship with the islands and their people?” Steve, at what point did you come to appreciate these disturbing political ramifications?

Steve: As soon as I arrived in Henoko, I could see the enormous economic gap between Americans and Okinawans, and sensed the American military’s condescending attitude toward the local people. Later I learned that many of those who worked on the bases or as bar hostesses and prostitutes in the vils’ were from farming families whose land had been forcibly seized by the U.S. military for base construction in the early to mid-various 1950s. This was one aspect of the economic and political oppression I witnessed under “occupation law” that prevented citizens from freely choosing their leaders in elections, and favored the U.S. military in property disputes, compensation settlements for deadly training accidents, and adjudications of G.I. crime. The late 1960s was the peak of the movement for Okinawa’s reversion to Japan where people lived under a civilian constitution and enjoyed prosperity in contrast to Third World conditions in Okinawa under American military rule. The daily protest rallies, marches, and sit-ins reminded me very much of the civil rights movement in the U.S. The Army told us that advocates for reversion were “Communists,” and warned us to stay away from their demonstrations. However, I learned much from bi-lingual fliers protestors distributed outside the base gates, from translated portions of mimeographed newsletters I read at the local library, and from people I met who could speak English. Okinawans were outraged that the bases were being used to kill other Asians in Vietnam. They also worried that, if the war escalated to a regional conflict, Okinawa as a major American support base would again be devastated as in the battle of 1945, but this time with the possible involvement of nuclear weapons stored there in large numbers. A Ryukyu University student told me “we have nothing against Americans personally, but are tired of the Pentagon running our island.”

Later, as a student in Tokyo I visited Okinawa in 1971, one year before reversion, but did not go back until 1983 to work on a translation of the novella “Cocktail Party” with the author, Oshiro Tatsuhiro. I’d read about how the Japanese government had broken its promise of a post-reversion Okinawa with the bases reduced to “mainland levels,” but it was still a shock to see how little the U.S. military presence had changed in the twelve years since my last visit.

Sarah: Since I actually lived in Okinawa, I have even less excuse for my ignorance than most, still I am stunned by how little Americans know about a chain of islands whose destiny we have controlled since the end of World War II. My hope for Above the East China Sea is that, through a fictional narrative, American readers will be engaged enough to investigate some of these complexities. Steve, to what do you attribute what George Feifer calls our “collective amnesia” on this topic? Is it as simple as that it suits the Pentagon’s purposes?

Steve: That’s why this novel is so important. This is the first of its kind in English, although Roger Pulvers’ Starsand (Bungakkai, April, 2012) in Japanese depicting two deserters, one American and one Japanese, is also set during the Battle of Okinawa. Your novel memorably informs Americans and other English-language readers not only about the trauma and devastation both sides inflicted on local residents, but also aboutt various aspects of Okinawan culture and history. The collective amnesia noted by George Feifer results from a widespread willingness to swallow unquestioningly official narratives and popular myths about the Battle of Okinawa and the postwar U.S. military presence there. The Japanese have their own amnesia about the battle which portrays Okinawans’ sacrifices, including many civilians who took their own lives, as “beautiful” acts of patriotism. We now know that these “suicides” were coerced by the Japanese Imperial Army. A young mother in Above the East China Sea believes she has “no choice but to jump” from a cliff to her death in the ocean. Otherwise, “the soldiers, either Japanese or American, will kill us as soon as the sun rises.” We also know today that the Japanese high command viewed Okinawa as a “throwaway pawn” in their wartime strategy. Recognizing that their forces would be destroyed by the Americans, the Japanese sought to inflict heavy casualties on the Americans and buy time for the battle on the Japanese mainland that they expected to follow. We now know that the Battle of Okinawa, the devastating fire-bombings of Japanese cities, and the nuclear attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki would never have happened if Emperor Hirohito had followed civilian advice to end the war in January, 1945.

According to the official U.S. narrative on the postwar military presence in Okinawa, 30,000 U.S. forces remain there seven decades after World War II to defend Japan and maintain regional security. Yet these have never been their true mission. Rather, they have stored weapons, maintained aircraft, trained 18,000 Marines for American deployments elsewhere, dispatched troops to fight in Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan.

By juxtaposing the coerced suicide of a young mother during the Battle of Okinawa and the near-suicide of an Air Force sergeant’s teen-age daughter mourning the death of her sister in Afghanistan, this novel conveys dramatically to readers the loss and suffering imposed continuously by war and aggressive U.S. military policies on Okinawans and Americans alike.

Sarah: Steve, you helped immeasurably on an op-ed I wrote that was recently published in the New York Times. I was dismayed because, for reasons of length, my editor had to cut your insightful comment on the Pentagon’s justification for our massive military presence on the island: “Do you really believe that 18,000 marines are there to ‘deter the Chinese?’ No, they are there to do routinetraining because it’s ‘good duty’ and cheap for the Pentagon on bases where facilities, land, electricity, and civilian services including golf course upkeep and lavish housing are paid for bythe Japanese government.”

Though I was deeply touched by the large number of messages of heartfelt appreciation I received from Okinawans after the piece was published, I was also subjected to a few diatribes from readers who believe that we provide “a free military” to the Japanese and others who compared me to Neville Chamberlain, with Okinawa being Sudetenland.

Steve: Actually, it’s the other way ‘round. The Japanese government pays for the U.S. military despite the fact that its mission there is far more likely to bring war on Japan than to defend the country. The comparison to Sudetenland recalls the U.S. military’s claim that Okinawans preferred American occupation which was bringing them “democracy” and “prosperity.”

Sarah: Steve, I have to mention again how foundational your work was to my project. No amount of historical, cultural, and political research could compare with the insight I gained about the Okinawan spirit from reading Southern Exposure: Modern Japanese Literature from Okinawa and Okinawa: Two Post-War Novellas. For me, nothing is as powerful as the empathic link a reader makes with a character. Do you have plans for other collections?

Steve: Yes, University of Hawaii Press is publishing a third collection of Okinawan literature in English translation, co-edited with Davinder Bhowmik. The working title is “Islands of Resistance: Japanese Literature from Okinawa.” It will include works by Medoruma Shun, Sakiyama Tami, and Yamanokuchi Baku.

From the book ABOVE THE EAST CHINA SEA. Copyright © 2014 by Sarah Bird. Reprinted by arrangement with Knopf, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Random House LLC.

Sarah Bird’s novel, Above the East China Sea was published in spring 2014 by Knopf and is excerpted here. This is her second novel set in Okinawa, following Yokota Officers Club.

Recommended citation: Sarah Bird with Steve Rabson, “Above the East China Sea: Okinawa During the Battle and Today,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Volume 11, Issue 22, No. 2., June 2, 2014.

Related articles

•Kinjo Shigeaki interviewed by Michael Bradley, “Banzai!” The Compulsory Mass Suicide of Kerama Islanders in the Battle of Okinawa

•Oe Kenzaburo, Misreading, Espionage and “Beautiful Martyrdom”: On Hearing the Okinawa ‘Mass Suicides’ Suit Court Verdict

•Aniya Masaaki, Compulsory Mass Suicide, the Battle of Okinawa, and Japan’s Textbook Controversy