The return to power of Abe Shinzō and his Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) unfolded as tensions on the Korean peninsula mount. As a key advocate of the abduction lobby, Abe’s rapid political rise since the early 2000s is closely connected with his role in promoting a hardline policy towards North Korea. Mobilizing a new nationalism in Japan, Abe’s return as prime minister in December 2012 signals a rightward shift in Japanese politics. The current international crisis surrounding North Korea offers a critical test for analyzing the trajectory of Abe’s foreign and security policy. In addition to joining multilateral United Nations sanctions, the Abe administration has increased the pressure on North Korea through new measures constraining the activities of pro-Pyongyang groups within Japan. Moreover, as Abe has pledged yet again to solve the abduction issue, the kidnapping problem has brought the old anti-DPRK policy network back to the forefront of Japan’s North Korea policy.

A lost decade

On 15 October 2002 the five abductees kidnapped by the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK, North Korea henceforth) during the 1970s and 1980s returned to Japan. As a result of secret diplomacy in preparation of direct talks between former Prime Minister Koizumi Junichirō and the late North Korean leader Kim Jong Il held on 17 September 2002 in Pyongyang, their return marked a historic success in Japan’s postwar diplomacy. The Pyongyang Declaration provided a roadmap for historical reconciliation and normalization of diplomatic relations between the two countries. Moreover, the declaration emphasised Japan’s commitment to resolving the controversy centered on North Korea’s nuclear and missile programs and was a rare signed commitment made by Kim Jong Il with regard to security and peace in Northeast Asia.1 Journalists and diplomats accompanying Koizumi on his trip to Pyongyang recognized the declaration as the main achievement of the summit. Back in Tokyo, however, the news desks of Japan’s major newspapers and television stations opted for the abduction issue as the main topic of the talks.2

Hence, as is well known, Koizumi’s overture of normalizing relations with Pyongyang was soon torpedoed by Japanese reaction to Kim Jong Il’s revelation of the North’s long suspected abduction of thirteen Japanese nationals, of whom eight have been declared dead by Pyongyang.3 While Pyongyang hoped that an official apology would put an end to the abduction issue, the revelations immediately caused public outrage and anti-DPRK resentment in Japan. In Japanese eyes, North Korea failed to provide convincing evidence regarding the fate of the remaining eight abductees. Thus, the issue remained, and continues to remain, a logjam in the normalization of Japan-DPRK relations. Moreover, Tokyo’s exclusive focus on the kidnappings has restrained Japan’s diplomatic space for manoeuvring within the working groups of the Six Party Talks framework launched in August 2003 adding to the malfunctioning process of security multilateralism in Northeast Asia.4

|

|

Following Koizumi’s return, Japan shifted its approach from dialogue to pressure, imposing a set of economic sanctions on North Korea and intensified pressure on pro-DPRK groups within Japan. Despite a second Koizumi visit to Pyongyang in May 2004 leading to the return of the families of those repatriated in October 2002, the abduction saga has effectively “kidnapped” Japan’s foreign policy process since 2002.5 North Korea has declared the issue to be “resolved” (kaiketsu sumi). In contrast, Japan demands watertight evidence on the remaining eight abductees that it insists are still in North Korea, declaring progress on the abduction issue a prerequisite for normalization of the nations’ bilateral ties.6 Commemorating the tenth anniversary of the return of the “Pyongyang Five” on 15 October 2012, criticism over Japan’s DPRK policy was voiced by the media calling the last ten years of Tokyo’s foreign policy towards North Korea a “lost decade” (ushinawareta ju-nen) in diplomacy.7 Despite the imposition of unilateral Japanese and U.S. sanctions and continued calls for stricter multilateral UN economic sanctions towards North Korea, Pyongyang has continued its nuclear and missiles programs; thus raising questions about the effectiveness of the measures currently imposed in order to force North Korea to engage in dialogue and to dismantle its nuclear facilities and ballistic missiles. Moreover, none of these sanctions has produced progress in the solution of the abduction issue.

Late signs of progress

As the ruling Democratic Party (DPJ)’s hold on power rapidly diminished, signs of progress to resolve the abduction issue as the key stumbling block in normalizing Japan-DPRK relations first came at the end of 2011 and then during the second half of 2012. After Kim Jong Il’s sudden death on 17 December 2011, Chief Cabinet Secretary Fujimura Osamu was quick to offer Japan’s condolence on the afternoon of 19 December.8 In fact, Japan issued a statement even before Washington did. Although Fujimura had to withdraw the official statement shortly thereafter due to pressure from within the government and the abduction lobby explaining they were his personal views, the move was considered a signal from Japan to reopen dialogue with the incoming regime in Pyongyang.9 For the first time since August 2008 Japan and North Korea agreed to hold working-level discussions between middle ranking diplomats from 28 August to 31 August 2012 at the Japanese embassy in Beijing.10 The meeting was widely viewed as an attempt by North Korea’s new leader Kim Jong Un to reduce tensions with Japan (and by extension with the United States) and to secure economic aid for his country’s ailing economy. During the meeting the two sides primarily discussed the repatriation of the remains of some 21,000 Japanese who died at the end of World War in the territory of what is today North Korea, and prospects for visits of Japanese relatives to graveyards in the North. In addition, the agenda included discussions on the repatriation of Japanese wives who joined their Korean husbands moving to the North in the 1950s and the extradition of Japanese who went to North Korea after hijacking a Japan Airlines flight in 1970 (the so called Yodogō group named after the plane).11 The August meeting was considered a success as both sides agreed to host further talks in 2012. Importantly, then Chief Cabinet Secretary Fujimura Osamu explained that the abduction issue would be part of the agenda, suggesting that North Korea has made concessions by departing from its previous stance claiming that the issue had already been resolved in 2002.12

With both sides agreeing to upgrade the meeting to senior-level talks, the two countries met again on November 15, 2012 in the Mongolian capital of Ulan Bator.13 The talks involved discussions between the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ Asian and Oceanian Affairs Bureau head Sugiyama Shinsuke and his North Korean counterpart Song Il Ho overseeing Japanese affairs within the DPRK’s Foreign Ministry.14 Convened shortly after Barack Obama’s reelection on November 6, the meeting was anticipated as a DPRK attempt to reopen dialogue with Washington through Tokyo. Moreover, some believe that North Korea is seeking ties with Japan as part of an effort to secure large-scale economic cooperation in order to implement economic reforms. While the meeting has produced no conclusions on the abduction issue, the North has agreed to continue the talks and to address the kidnappings. Japanese diplomats praised the meeting as having produced “minimal progress” in a positive sense and both sides agreed to continue the talks in December 2012.15

The attempt to break the decade-long diplomatic stalemate in Japan-DPRK relations came at a time of turmoil in Japanese domestic politics. Only one day before the Ulan Bator meeting, former Prime Minister Noda Yoshihiko dissolved the Diet’s lower house on 14 November, opening the way for elections on 16 December. While Noda’s DPJ and his cabinet were down in the surveys the incumbent administration pushed for talks with the DPRK in an effort to achieve some significant progress on the foreign policy front. Japanese media reported that in October the prime minister’s office had expressed a desire to hold talks in Ulan Bator advising MOFA officials to accelerate the process of scheduling the senior-level meetings. The reports stated that the preparations for renewed talks with the DPRK went slowly until the intervention by the PM’s office.16 Improving relations with North Korea was seen as critical for the DPJ as Noda’s opponent and new LDP president Abe Shinzō had built his political career primarily based on advocating a hard line against North Korea imposing pressure on Pyongyang through a series of economic sanctions introduced during his first term as prime minister in 2006. More than anything, a success in engaging North Korea in dialogue and securing concessions over the abduction issue would have provided Noda with a positive story deflecting media attention from the DPJ’s heavily criticized ‘soft’ foreign policy approach towards managing the territorial disputes with China and South Korea. Thus, while electoral defeat of the DPJ appeared unavoidable at this point, demonstrating foreign policy competence in dealing with North Korea in contrast to Abe’s containment approach might have limited the scale of defeats.

The return of Abe

Another round of bilateral senior-level talks was scheduled for 5-6 December in Beijing, ten days ahead of Japan’s general elections. However, in response to North Korea’s announcement that it would launch an “Earth observation satellite”, but was widely viewed by international society as a test of the three-stage long-range missile Unha-3, the Japanese government postponed the meeting.17 Indeed, Japan mobilized the Japan Self Defense Forces (JSDF) and announced that it would shoot down any debris that infringed on Japanese territory. Following the missile launch that passed over Okinawa on 12 December, Tokyo criticised the test as “extremely regrettable”. Only four days ahead of Japan’s general elections North Korea entered the campaign, adding prominence to national security issues.18

The LDP’s return to power was preceded by the election of Abe Shinzō as party president in September 2012, defeating his main opponent and hawk Ishiba Shigeru. The LDP’s electoral advances were mainly a product of public disapproval of the Democrat’s post-3.11 crisis management and the DPJ’s party internal conflicts and scandals. However, ongoing regional tensions caused by the infringement of Chinese vessels into the disputed territory of the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands, the eruption of anti-Japanese riots in China, and the conflict with South Korea over the Dokdo/Takeshima islands escalating after the South Korean president Lee Myung Bak made an unprecedented visit to the islands on 10 August 2012 together paved the way for a revisionist and nationalist policy agenda to gain momentum in Japan. Thus, while the Abe campaign emphasized economic reform and inflation targets in an attempt to end Japan’s deflation-driven long-term recession, the LDP’s promise to strengthen Japan’s military capabilities, to revise Japan’s pacifist constitution in order to enable Japan to participate in collective self-defense, and Abe’s promise to revise Japan’s record of reconciliation and apology regarding war atrocities such as the “comfort women”, have raised concerns over a shift of Japan to the right.19

|

|

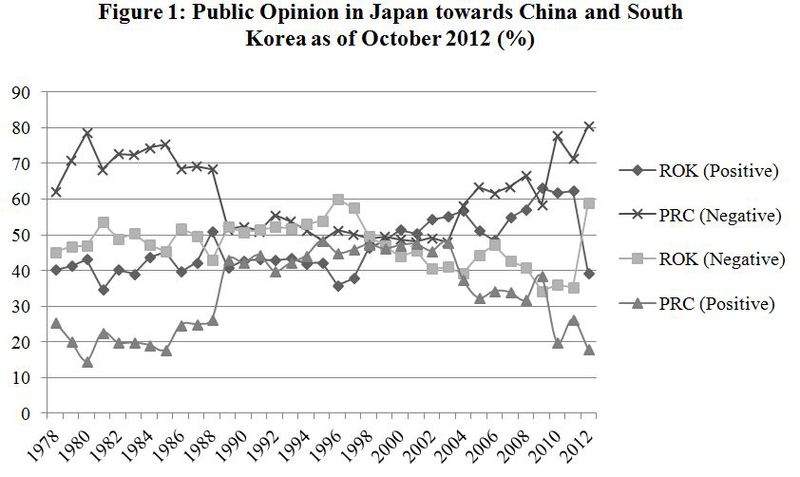

History and political science have frequently pointed at the complex role of ‘timing’ in the study of success and failure of policies, political leaders and cabinets.20 Distressed by economic reforms and bilateral tensions between Japan and its regional neighbours at the end of Koizumi’s long-term premiership (2001-2006), Abe misread Japan’s public mood at the launch of his first cabinet in September 2006. Though the electorate expected Abe to continue the structural reforms initiated by Koizumi, he back-pedaled. Abe disappointed voters by reintegrating opponents of postal privatization into the LDP. The announcement that 50 million pension records were lost further destabilized his cabinet. Amidst scandals involving cabinet ministers that have seriously tainted the credibility of his administration, Abe’s emphasis on reform of Japan’s basic education law introducing patriotism in Japanese classrooms, the upgrading of the Defense Agency to the Ministry of Defense, and legislation on public referenda for constitutional revision created a misfit between Abe’s nationalist agenda and the public’s concern over “bread-and-butter” economic issues. Facing rapidly shrinking support rates, Abe abruptly resigned in September 2007. The LDP’s historic electoral defeat followed soon after, in August 2009. The problem of rapid turnover of Prime Ministers continued thereafter. The average length of a minister’s service in government under the DPJ’s Hatoyama and Kan was 8.7 months, in contrast to 18.6 months under Koizumi).21 However, as the survey data presented in figure 1 illustrates, disputes with China and South Korea in combination with mounting tensions on the Korean peninsula created a political context ripe for a return of Abe, whose high support rates (according to Jiji Press 61% as of 15 March 2013) suggest that he has found a balance between pursuing nationalist policy goals and advocacy of an economic reform agenda. The dramatic shift in public opinion towards South Korea and China between 2009-2012 illustrates the context for Abe’s revival and the rise of right-wing populism in the form of the electoral advance of the newly established Japan Restoration Party (JRP) of Hashimoto Toru and Ishihara Shintarō, which won 54 seats in the recent elections (three seats less than the DPJ.22 The figure shows that while public attitude towards China has continuously been negative, expression of an anti-China attitude spiked since 2010. The tensions that erupted between Japan and China over the collision of a Chinese fishing vessel with two Japanese Coast Guard ships in the waters surrounding the Senkakus in September 2010 eroded Japanese public trust in China. The Chinese crew and their captain were taken into Japanese custody and only freed after China employed economic pressure through restricting exports of rare earth minerals to Japan. Similarly, the recent conflict with South Korea over the Dokdo/Takeshima islands has resulted into a dramatic increase of negative attitudes towards Seoul since 2011.

Of course, Abe’s landslide win in the December elections (the LDP won 294 seats, and commands, together with its New Kōmeitō coalition partner, an absolute majority) cannot solely be traced back to concerns over foreign policy issues. In fact, the public was primarily concerned with domestic issues. This being the case, the DPJ was negatively evaluated for an unpopular tax reform (passed in August 2012 with support of the LDP) to finance the ailing social security system and reduce Japan’s mounting debt. Slow progress in the post-disaster recovery of the Tohoku region and criticism of the DPJ’s crisis governance significantly reduced trust in the DPJ. Finally, with the lowest voter turnout (59.32%) in Japan’s post-war electoral history, the Japanese made it quite clear that after tumultuous years of political instability there is in fact no party that one can confidently support. For this reason it may be too early to speak of a rightward shift in Japanese politics and the emergence of a new nationalism in Japan.23 Yet, territorial conflicts with China and Korea not only undermined DPJ stability since 2010, they also shifted public opinion in Japan towards Seoul and Beijing. In this context, Abe’s nationalist rhetoric promising to revise Japan’s pacifist constitution, to re-examine the 1993 Kōno statement on the ‘comfort women’ issue, and to enhance Japan’s military capabilities by upgrading the Japan Self-Defense Forces (Jieitei) to National Defense Forces (Kokubōgun) constitutionally capable of engaging in collective self-defense sounded more compelling to many Japanese.24

Henceforth, as tensions mount in Northeast Asia and the advance of nationalist political forces in the form of the JRP, which shares many of the revisionist views held by hawks within the LDP (Hashimoto and Ishihara strongly advocate constitutional revision, while Ishihara calls for Japan’s nuclear armament25 Hashimoto has made news with his tweets in denial of the ‘comfort women’ issue26), the return of Abe has spurred intense debate on the trajectory of Japan’s new nationalism. More importantly, however, as the driving force behind Tokyo’s hard line approach towards the DPRK since 2002, Abe’s return to power raises important questions on how Japan will address the renewed challenges posed by North Korea’s December missile launch and the February nuclear test that coincided with the start of the second Abe cabinet.

The struggling abduction apparatus

The rise and influence of Abe Shinzō and the abduction issue are closely related. Abe’s sudden political prominence in the early 2000s pivoted on his advocacy of an assertive diplomacy towards the DPRK as a key figure in the abduction lobby. Conversely, the political movement that has emerged in response to the abduction issue has provided Abe a key platform. As a third generation politician,27 Abe entered the world of politics in the 1980s first as the personal secretary of his father Abe Shintarō, who served as foreign minister and LDP general secretary. The young Abe inherited his father’s Yamaguchi constituency for a lower house seat in 1991 and became a member of the Diet in 1993. Abe first learned about the abduction case in 1988 while serving as his father’s secretary. The parents of Arimoto Keiko, who was abducted from Europe in 1983 sought help from Abe Shintarō, then LDP general secretary. However, the public paid little attention to the abduction cases in the late 1980s and the first half of the 1990s. The abduction victims’ family members as well as his close political associates approved of Abe Shinzō’s early devotion to support of the victims’ families and the advocacy of the abduction issue. As Abe was elected to the foreign affairs committee of the House of Representatives, he raised the abduction issue repeatedly in 1997 and strongly criticized the state’s failure to protect Japanese citizens from harm and referred to North Korea as a “terrorist state”.28 While the abduction issue became Abe’s lifework, the problem provided him with an important basis for his explicit criticism of what he has prominently described as Japan’s “postwar regime”. Thus, he insists, under Japan’s constitution prohibiting the possession of military force, postwar Japan was unable to adequately protect its citizens. Therefore, in the version of nationalism that Abe and his associates propound, the abduction issue is causally linked to normative claims for an autonomous state (jiritsu suru kokka) able to protect Japan from infringement on its sovereignty, demanding constitutional revision, an enhancement of Japan’s military capability, and active role of Japan as a “normal state” in international politics. This narrative has found expression in Abe’s 2006 political manifesto “Towards a beautiful country” (utsukushii kuni e) and the modified 2012 version “Towards a new country” (atarashii kuni e).29 Yet, while Abe has moved quickly to announce a 1.4 billion dollars increase in the nation’s defense budget for 2013, he has toned down his nationalist rhetoric. Seeking to secure a majority in the July upper house elections, Abe has focused on economic reforms (nicknamed ‘Abenomics’) during his first few months in office, succeeding in bringing the Bank of Japan in line with his two-percent inflation rate policy, and preparing the LDP for battling with domestic vested interests over Japan’s participation in the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) agreement.

Under Prime Minister Mori Yoshirō, Abe was appointed deputy chief cabinet secretary in 2000 and re-appointed in 2001 after Koizumi succeeded Mori. In this post, Abe consolidated his reputation as the advocate of the abduction lobby and was known within the Kantei for his hardline policy stance vis-à-vis North Korea. Therefore, during secret negotiations in preparation of the 17 September 2002 meeting between Koizumi and Kim steered by then director general of MOFA’s Asian and Oceanian Affairs Bureau Tanaka Hitoshi, Abe was kept out of the loop. Fearing that he could oppose the summit meeting and leak information to the abduction lobby and media, Abe was not briefed on the trip until the end of August 2002. Nevertheless, Abe accompanied Koizumi to Pyongyang in September. His political ascendency occurred at this critical juncture of Japan’s attempt to open dialogue with North Korea, famously demanding that Koizumi leave the meeting if Kim Jong Il did not offer an official apology for the abductions.

Despite Kim’s public acknowledgment and apology, back in Japan the Pyongyang summit evoked public outrage over the abductions. The post-summit protest and gradual policy shift from engagement towards containment of North Korea was directed by an empowered political movement whose point of unity was the abduction issue. The reporting of the case of Yokota Megumi, who was abducted in November 1977 as a thirteen-year-old junior high-school student from Niigata, was the pivotal moment for the mobilization of the abduction lobby. While Megumi became the poster-child of the movement, her parents Yokota Shigeru and his wife Sakie were at the centre of the Association of the Families of Victims Kidnapped by North Korea (Kitachōsen ni yoru ratchi higaisha kazoku renraku kai, Kazokukai) launched in March 1997. The Kazokukai’s support organisation, known under the name National Association for the Rescue of Japanese Abducted by North Korea (Kitachōsen ni rachisareta nihonjin o kyūshutsu suru tame no zenkoku kyōgikai, Sukuukai), was set up in September 1997. At the time of its launch the Sukuukai was closely affiliated with the Modern Korea Research Institute, whose director Satō Katsumi became the central figure embedding the abduction issue in a broad foreign policy agenda that called for tough economic sanctions and regime change in North Korea as a prerequisite to solving the kidnapping saga. The third pillar of the movement was the Assembly Members Alliance for the Speedy Rescue of Japanese Kidnapped by North Korea (Kitachōsen ni ratchisareta nihonjin o sōki ni kyūshutsu suru tame ni kōdō suru giin renmei, Ratchi giren) – a bipartisan group of Diet members functioning as the parliamentary gateway for the movement.

Since the return of the “Pyongyang Five” the basic structure of the abduction apparatus has largely remained unchanged. And yet, as the abduction cases remain unsolved the movement has struggled to maintain momentum. In 2008, Sukuukai’s director Satō Katsumi left the movement and Nishioka Tsutomu emerged as the leader. Satō claims that he became an outspoken critic of the DPRK-regime after he himself helped, as an ex-communist, to send thousands of Zainichi Koreans to North Korea in the late 1950s and 1960s. The circumstances of Satō’s withdrawal, however, have resulted in public speculation over an internal power struggle between Satō and Nishioka over the alleged disappearance of large sums of donations. As a self-proclaimed North Korea expert and university lecturer who avoids appearances at academic conferences, Nishioka is an outspoken hawk arguing for Japan’s remilitarization and use of force in the solution of the abduction issue.30 After his retreat from leadership, Satō harshly criticized Nishioka over his use of funds and his leadership of the movement. As a cold-war activist, Satō claims the creation of a national political movement that has increased Japan’s leverage in negotiating with North Korea and forestalled normalization talks as his personal success. In his eyes, today’s Sukuukai has lost its momentum and degenerated into a “university circle” that fails to attract large crowds. Moreover, reflecting on his relationship with Abe, Satō accredits Abe’s political success to his dependence on the abduction network’s support. Thus, the primary reason why the abduction movement lost momentum rests, in Satō’s view, in the fact that Nishioka mainly focused on increasing his political influence within Abe’s DPRK policy process.31

In addition to the cleavages at the movement’s top, a multitude of rifts have emerged within the abduction lobby. A rift emerged between the abduction victim families whose loved ones returned and those whose relatives were declared dead and who felt betrayed by the declining engagement of the victims’ families in the movement. Even within the Yokota family a rift occurred over the course of the movement, with Yokota Sakie supporting the claim for enhanced economic sanctions and her husband Shigeru publicly expressing doubts over the effectiveness of such sanctions.32 Moreover, while at its peak in the years 2003 to 2005 the abduction lobby’s national network maintained more than one hundred offices, the movement shows signs of disintegration at the local level. For example, in areas such Tohoku, the Miyagi branch of Sukuukai has distanced itself from the hierarchical leadership style adopted by Nishioka and his Sukuukai.33 These newly autonomous groups team up with new right-wing groups such as the 2006 launched Citizens against Special Privilege of Zainichi (Zainichi tokken o yurusanai shimin no kai, nicknamed Zaitokukai) who have incorporated the abduction issue into their tirades of hate speech.34 The emergence of the Zaitokukai as a new brand of reactive nationalism actively using social network services (e.g. the Japanese video portal nico nico dōga) to disseminate their disturbing messages calling for eviction (and even death) of Zainichi Koreans.35 This new reactive nationalism has added to the decentralization of the abduction movement while the kidnapping cases further nourish a strong anti-DPRK attitude within Japan.

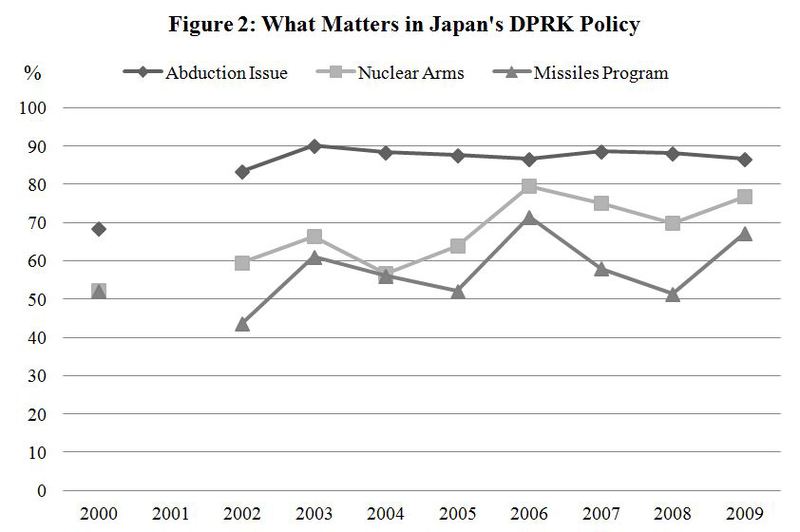

Despite the changes within the abduction lobby, its influence measured based on public perception of the issue remains high. According to a Cabinet Office survey of October 2012 the abduction issue remains the top concern with respect to the DPRK (up from 84.7% in 2011 to 87.6%) among Japanese with a widening gap to the North’s missile (49.6%) and nuclear threats (59.1%). These numbers strongly correspond to the overall picture since 2002 as shown in figure 2.36 The abduction issue has remained atop Japan’s DPRK policy agenda.

|

|

The enormous political influence of the abduction lobby and its close ties to the Japanese right has restrained debate on the issue within Japan’s public sphere and resulted in cases of intimidation of Zainichi Koreans as well as critiques of the current course of Japan’s North Korea policy. After Abe became Prime Minister in 2006 he specifically ordered NHK to increase coverage of the abduction issue on its overseas broadcasts which are directly funded by the Japanese government.37 This was not the first case Abe has censored NHK programs. As deputy chief cabinet secretary, he forced NHK to remove testimonies given by Japanese soldiers on the comfort women made at the 2000 Women’s International War Crimes Tribunal on Japan’s Military Sexual Slavery from a documentary aired in January 2001.38 Shortly before Abe became Prime Minister censorship and intimidation of journalists and academics continued. On 12 August 2006 Sankei’s Washington correspondent Komori Yoshihisa fiercely attacked Tamamoto Masuru, the editor of the online Commentary of the Japan Institute of International Affairs (JIIA). In an article, Tamamoto expressed concerns over the emergence of a “hawkish nationalism” in Japan embodied in Yasukuni shrine visits of the Prime Minister and increasingly shrill anti-China rhetoric. Sankei’s Komori attacked the piece as “anti-Japanese” and demanded that JIIA president Satō Yukio apologize for using taxpayers’ money to publish a piece critical of the Japanese leadership. Within 24 hours the article disappeared from JIIA’s homepage and Satō promised the Sankei editors to overhaul JIIA’s editorial board.39 Also in August 2006 extremists burned down the parental home of LDP veteran Katō Kōichi after he criticized Koizumi’s Yasukuni visits, and Fuji Xerox chairman Kobayashi Yotarō was targeted by firebombs after he voiced concerns over the Yasukuni issue. In 2003, Tanaka Hitoshi, the chief-diplomat behind Koizumi’s DPRK-policy was also the target of bomb threats. Then Tokyo governor Ishihara Shintarō commented that Tanaka “had it coming”.40

The Kobe District Court on 4 November 2011 ordered the journalist Tahara Soichirō to pay 1 million yen in compensation to the parents of Arimoto Keiko who was abducted in 1983 from Europe. Tahara was sued in July 2009 over mental distress suffered by Keiko’s parents after he remarked during a TV Asahi debate program that Arimoto Keiko must already be dead. Tahara based his statement on sources from within MOFA. After the abductions became a public issue in September 2002 Japanese neonationalists targeted the Zainichi Korean community and particularly their pro-DPRK groups. For example in September 2003 a right-wing group called Nippon Kofugun (Japan Imperial Grace Army) doused a car with gasoline in the parking lot of the Oita office of the General Association of Korean Residents in Japan (Chongryun). The group alerted the police as well as Kyodo News Agency, claiming they attempted to set it ablaze to “face down” Kim Jong Il.41 In a similarly disturbing act, on 4 December 2009 local members of Zaitokukai went to the Korean elementary school run by Chongryun in Kyoto to intimidate children and teachers, shouting “Leave Japan, children of spies” and “This school is nurturing North Korean spies”.42 The incident led to the arrest of a janitor, a snack bar owner, an electrician, and a company employee who led the provocative act in August 2010. The arrest, however, further stimulated the Zaitokukai movement.43

Increasing pressure

As the abduction issue’s primary advocate, Abe has spearheaded the imposition of unilateral sanctions against North Korea. In 2004 he pushed the revision of Japan’s Foreign Exchange and Foreign Trade Law tightening the procedures required for remittances by DPRK-affiliated Koreans in Japan. Moreover, Japan prohibited the entry of DPRK ships (the primary target is the passenger ship Manyongbong-92) into Japanese ports in June 2004, and blocked food aid to the North since December 2004.44 The abduction lobby pressed for stricter supervision of Chongryun affiliated credit unions (Chōgin) as well as the removal of local tax exemptions for Chongryun-affiliated organizations in Japan in 2006. While planning for most of these sanctions was begun under Koizumi, Abe moved quickly to further strengthen the sanctions regimes in 2006. Even before UN Security Council Resolution 1718 was adopted on 14 October 2006 in response to North Korea’s first nuclear test, Japan introduced sanctions that closed all Japanese ports to North Korean ships and cargo, and visits by North Koreans to Japan. Later, these sanctions were strengthened by bans on trade in luxury goods and further restrictions on remittances. Under Abe, economic sanctions were accompanied by institutional structures in form of the Headquarters for the Abduction Issue (Ratchi taisaku honbu) and a state minister in charge of the problem commanding a hefty budget. After the electoral victory of the DPJ in August 2009 these structure remained in place with stable bipartisan support for the abductions lobby in the Diet. Yet other factors may have been more important than the sanctions in isolating the DPRK. While Japan’s share of DPRK trade was estimated at 17.8 per cent in 2001 it declined to 4.8 per cent in 2005, limiting the impact of sanctions even before their imposition in 2006.45

|

|

Pro-Pyongyang groups in the Zainichi community are the chief target of Japanese pressure. The abduction lobby and right-wing eliminated preferential tax treatment of pro-DPRK organizations. For example, in December 2003 then Tokyo governor Ishihara ended Chongryun’s tax exemptions. In February 2006, the Fukuoka High Court ruled that the Kumamoto Korean Hall owned by Chongryun in Kumamoto does not benefit the general public and is therefore not eligible for exemption from local taxes.46

This is part of a general decline of the role of Chongryun in Japan. In March 2013 the pro-Pyongyang group has de facto lost possession of its central headquarters that has functioned as North Korea’s ‘quasi embassy’ in Tokyo. Chongryun suffered massive financial troubles after its network of 38 banks and credit unions rapidly went broke in post-bubble Japan mainly due to remittances to the North during the catastrophic famine in the mid-1990s. After the Japanese government provided an emergency bailout in the late 1990s, Chongryun ended up owing Japanese authorities nearly 750 million dollar.47 In an attempt of to recover some of the 62.7 billion yen, Chongryun’s central headquarters has been repossessed by the Japanese government and placed on sale.48 Based on a 2007 decision of the Tokyo District court, the real estate was seized by the Resolution and Collection Corporation (RCC) in order to recover Chongryun’s debt. The bidding took place during 12-19 March 2013. The winning bidder was the Shingon Buddhist Sect’s Saifukiji temple based in Kagoshima. Its priest Ikeguchi Ema is said to be a frequent visitor to Pyongyang. Ikeguchi agreed to rent out the building to Chongryun.49 Chongryun not only lost ownership of its headquarters, but it has been suffering a decline in membership. Currently, Japan counts 545,000 Zainichi, of whom 395,000 affiliate with South Korea. It is estimated that 20 to 30 DPRK-affiliated Zainichi change their registration to an ROK-affiliated status every month.50 Chongryun is gradually disintegrating and with it its influence in managing Japan-DPRK relations.

Following Pyongyang’s launch of a long-range ballistic missile in December 2012, the Abe administration announced further measures.51 It further tightened the screws by prohibiting senior Chongryun leaders from re-entering Japan after visiting North Korea. So far, Japan only bans top executives from re-entering the country. Moreover, proposed sanctions include the lowering of remittances to North Korea that are required to be reported (currently this amount is 3 million yen). In addition, the new Abe government’s education minister Shimomura Hakubun has instructed his ministry to exclude private high schools affiliated with North Korea from its program of providing free high school education.52 The decision was officially passed on 20 February 2013 affecting ten pro-DPRK schools of have applied for tuition aid to the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT). The media quotes Shimomura as saying “The schools are under the influence of the General Association of Korean Residents in Japan (Chongryon) and (making them eligible for the program) may violate the Basic Law of Education, which stipulates that ‘education shall not be subject to improper control’”.53 The tuition waivers were introduced by the DPJ in April 2010 targeting all high schools in Japan including 39 international and ethnic schools. Hence the criticism, that the recent decision is “blatant racism” against ethnic minorities. Opponents such as Osaka University’s Morooka Yasuko are now appealing to international organizations such as the UN to reverse the decision.54 The Asahi Shimbun reported on 19 February that seven prefectures (Miyagi, Saitama, Chiba, Tokyo, Kanagawa, Osaka, Hiroshima) have decided to withhold subsides to pro-DPRK schools in their budgets for the 2013 fiscal year. On 22 February Yamaguchi prefecture announced that it was halting school subsidies, and Niigata prefecture followed on 29 March 2013. The Japan Federation of Bar Associations has explained that, under the constitution, these decisions are discriminatory acts that should be reversed.55

In the aftermath of Pyongyang’s nuclear test on 12 February, the UN’s security council unanimously passed Resolution 2094 on 7 March 2013. The UN’s multilateral sanctions target the travel of DPRK diplomats, North Korean cash transfers and the import of luxury goods.56 On 5 April 2013 Japan followed this initiative extending its total ban on all trade with North Korea as well as bans on DPRK ships entering Japanese harbors for another two years. Moreover, Japan has announced that it will follow the US lead and black-list North Korea’s Foreign Trade Bank. As the North’s main exchange bank, this institution is believed to play a vital role in financing the North’s nuclear development program.57 Tokyo’s decision was made public on 26 March 2013, and states that Japan would be ready within two to three weeks to implement measures. Reuters quotes a government source as saying, “The (bank) doesn’t have a branch in Japan so the main reason behind the move is an attempt to cause as much reputational damage as possible,” that is to constrain trade between the DPRK bank with other financial institutions. Japan’s chief cabinet secretary Suga Yoshihide has pledged that Japan will impose financial sanctions based on US measures. Moreover, in a phone-conversation with US President Obama in February 2013, Abe embraced Washington’s lead to strengthen financial measures explicitly referring to the efficient freeze of DPRK assets at the Macau-based Banco Delta Asia between 2005-2007.58

|

|

Emphasizing his willingness to renew the issue’s priority, on 29 January 2013Abe launched a Bipartisan Council on the Abduction Issue. The council includes lawmakers from the LDP, DPJ, JRP and Your Party, and replaces the abduction headquarters of the previous DPJ government. As such, Abe’s ‘all Japan’ approach towards the abduction issue brings into the Kantei the abduction lobby’s most renowned advocates of stricter DPRK-sanctions including Nakayama Kyoko and Hiranuma Takeo (both JRP). As such, the abduction issue allows Abe to intensify policy dialogue with the JRP which is currently the third largest opposition party and crucial for passing constitutional revision in the Diet. Abe has appointed former Rachigiren secretary-general Furuya Keiji as minister in charge of the abduction issue and thus the new council. In his policy speech to the Diet on 28 January 2013 Abe stated that his “mission will not be finished until the day arrives that the families of all the abductees are able to hold their relatives in their arms” while defining the conditions of progress as “ensuring the safety and the immediate return to Japan of all the abductees, obtaining a full accounting concerning the abductions, and realizing the handover of the perpetrators of the abductions.”59 The Abe government has allocated 1.2 billion yen to the abduction issue in the 2013 budget, in contrast to the DPJ, which refrained from fully using the allocated budget in the last fiscal year. Finally, on 3 April 2013 the council on the abduction issue was located within the Prime Minister’s office. While Abe has restated his willingness to push for a solution of the issue within his premiership, his government has renewed the ban on all imports and exports for two more years. A look at the composition of the advisers appointed to the Kantei council dealing with the abduction issue suggests more pressure and less dialogue, as many of its members are known for their hawkish views and are directly affiliated to the abduction lobby and as such long-time companions of Abe. The new advisory board includes former Sankei correspondent Komori Yoshihisa, Korea specialist and former Yonsei University Professor Takesada Hideshi, Shizuoka Prefectural University Professor and DPRK expert Izumi Hajime, Sukuukai director Nishioka Tsutomu, Sukuukai’s vice-director Shimada Yoichi, Takushoku University Professor and Araki Kazuhiro60, the lawyer Kawahito Hiroshi, and top figures of Kazokukai Masumoto Teruaki, and Iizuka Koichiro.61

Yet another lost decade

Despite signs of progress in Japan-DPRK relations during the second half of 2012, the return of Abe and the most recent missile and nuclear tests by North Korea have diminished hope for progress in the near future. Despite Abe’s pledge in his January policy speech before parliament to bring the abduction issue to a solution, Japan has imposed new measures intensifying pressure on the Zainichi community since January 2013. Intensified cross-border trade relations between China and North Korea have raised criticism within Japan over the effectiveness of the current sanctions regime.62 Moreover, Japan’s territorial disputes with China and South Korea have rendered policy coordination over the North Korean problem increasingly difficult. While the second Abe administration has prioritized economic reform and Japan’s participation in the TPP free trade pact, Abe has revitalized the abduction lobby as a tool for symbolic politics and as part of increasing pressure on North Korea. However, given the internal struggles of the movement and the advanced age of its members, it remains to be seen whether or not the abduction lobby will be able to further hold Japan’s DPRK-policy hostage.

Sebastian Maslow is Assistant Professor at the Centre for East Asian Studies, Heidelberg University and a doctoral candidate at the School of Law, Tohoku University. His research focuses on Japan’s foreign policy process and Japan-North Korea relations.

Recommended Citation: Sebastian Maslow, “Yet Another Lost Decade? Whither Japan’s North Korea Policy under Abe Shinzō,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 11, Issue 15, No. 3, April 15, 2013.

1 For an English translation of the original text of the Pyongyang Declaration see http://www.mofa.go.jp/region/asia-paci/n_korea/pmv0209/pyongyang.html (accessed 5 April 2013).

2 Interview Ishikawa Ichirō, Nihon Keizai Shimbun, Tokyo, 21 August 2011. In fact, many of Japan’s newspapers have witnessed internal struggles between the society and politics sections over how to cover the summit results, with the society section usually emphasizing the abductions. Moreover, newspaper journalists blame the so-called ‘wide shows’ (i.e. tabloid-style programs) on Japanese TV that have repeatedly focused on the human drama of the abduction cases, thus setting the tone for the national debate and forcing newspapers to emphasize the kidnappings in their front page headlines. See Aoki Osamu. Repo ratchi to hitobito: Sukuukai, kōan keisatsu, chōsen soren (Tokyo: Iwanami shoten, 2011).

3 As of today, the Japanese government recognizes 17 people that it believes were abducted by North Korea. For a comprehensive list of the abduction victims and accounts of the circumstances of their disappearance see here (accessed 6 April 2013).

4 For a critical analysis of Japan’s role in the Six Party Talks see Maaike Okano-Heijmans. “Japan as Spoiler in the Six-Party Talks: Single-Issue Politics and Economic Diplomacy Towards North Korea.” Japan Focus, 21 October 2008.

5 Asger Røjle Christensen (2012). “Japan: Abducted by Its Abduction Saga.” Global Asia, Volume 7, Number 4, pp.116-123

6 For the official Japanese government interpretation of the abduction cases see here (accessed 5 April 2013).

7 Newsweek (Japan), 24 October 2012.

8 The relevant video footage and text of the press statement issued by the Chief Cabinet Secretary can be accessed here (accessed 6 April 2013).

9 The episode is presented in an interview between Hirai Hisashi and Lee Jong Won featured in Sekai (March 2012), p.234.

10 For details on the meeting see here (accessed 5 April 2013) and here (accessed 5 April 2013).

11 For a discussion on the outcomes of the August 2012 meetings see here (accessed 5 April 2013).

12 See the official summary of the August meeting by Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (accessed 5 April 2013).

13 See here (accessed 5 April 2013).

14 See here (accessed 5 April 2013).

15 For a summary of the November meeting see here (accessed 5 April 2013) and here (accessed 30 March 2013).

16 The Japan Times quotes unnamed government sources for Noda’s effort to hold early talks; see here (accessed 5 April 2013).

17 See here (accessed 5 April 2013).

18 Amy L. Catalinac. “Not Made in China: Japan’s Home-Grown National Security Obsession.” East Asia Forum (6 March 2013) (accessed 8 April 2013).

19 See Tessa Morris-Suzuki. “Freedom of Hate Speech; Abe Shinzo and Japan’s Public Sphere.” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol.11, Iss.8, No.1, February 25, 2013, available here.

20 See Paul Pierson. Politics in Time: History, Institutions, and Social Analysis (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2004).

21 Gerald Curtis. “Can Japanese Politics be Saved?” East Asia Forum (13 November 2012) (accessed 8 April 2013).

22 For the results of the December 2012 lower house elections see here (accessed 6 April 2013).

23 See Toshiya Takahashi. “Oversimplifying Japan’s Right Turn.” East Asia Forum, 28 March 2013 (accessed 11 April 2013).

24 See Gavan McCormack. “Abe Days Are Here Again: Japan in the World.” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol.10, Iss.52, No. 1, December 24, 2012.

25 In a recent interview with the Asahi Shimbun Ishihara renewed his call for a Japan with nuclear weapons; see here (accessed 6 April 2013).

26 See Tessa Morris-Suzuki. “Out With Human Rights, In With Government-Authored History: The Comfort Women and the Hashimoto Prescription for a ‘New Japan.’” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol.10, Iss.36, No.1, September 3, 2012 .

27 As is well known, Abe’s grandfather was Kishi Nobusuke, a former ranking official in Manzhoukuo and an unindicted war criminal under the occupation who rose to prime minister and LDP president.

28 Nogami Tadaoki. Dokyumento Abe Shinzo kakureta sugao wo ou (Tokyo: Kodansha, 2006), p.28.

29 Both books published under these Japanese titles by Tokyo-based Bungei shunju.

30 Interview Nishioka Tsutomu, 19 August 2011, Tokyo.

31 Interview Satō Katsumi, 8 October 2011, Tokyo. The investigative journalist and former Kyodo reporter Aoki Osamu has presented the most detailed account yet on the movement’s internal rifts and power struggles in his Repo ratchi to hitobito: Sukuukai, kōan keisatsu, chōsen soren (Tokyo: Iwanami shoten, 2011), and here esp. pp.80-84.

32 Yamada Toshihiro. “Ratchi higaisha, 10nen me no genjitsu.” Newsweek (24 October 2012), p.30.

33 Interview, Ando Tetsuo (chair of Sukuukai Miyagi), 1 September 2012, Sendai.

34 On the Zaitokukai Yasuda Koichi’s recently published account Netto to aikoku: zaitokukai no ‘ami’ wo oikakete (Tokyo: Kodansha, 2012).

35 See Maslow (2011). “Nationalism 2.0 in Japan.” Asian Politics & Policy, Vol.3, Iss.2, pp.307-310. On the rise of reactive nationalism in Japan see Apichai W. Shipper’s 2010 article “Nationalisms of and Against Zainichi Koreans in Japan.” Asian Politics & Policy, Vol.2, Iss.1, pp.55-75.

36 For the data see http://www8.cao.go.jp/survey/h24/h24-gaiko/2-1.html (accessed 30 March 2013).

37 See for example Tessa Morris-Suzuki. “Free Speech – Silenced Voices: The Japanese Media, the Comfort Women Tribunal and the NHK Affair.” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 13 August 2005.

38 On the ‘comfort women’ issue see Tessa Morris-Suzuki. “Japan’s ‘Comfort Women’: It’s Time for the Truth (In the Ordinary, Everyday Sense of the Word).” Japan Focus, 7 March 2007.

39 The case is described by Steve Clemons in his Washington Post op-ed “The Rise of Japan’s Thought Police” published on 27 August 2006. Komori responded in his op-ed “Who’s Afraid of Shinzo Abe?” published in The New York Times on 30 September 2006.

40 See Sebastian Maslow. “Right-Wing Politics in Postwar Japan (1945-Present).” In Louis G. Perez (ed.). Japan at War: An Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara: ABC Clio, pp.335-337. Year?

41 See here (accessed 7 April 7, 2013).

42 See here (accessed 7 April 2013).

43 Other cases of Zaitokukai members intimidating local authorities and teachers are reported in Yasuda’s Netto to aikoku.

44 The full list of Japan’s economic sanction apparatus towards North Korea is available here (accessed 11 April 2013).

45 Yokoto Takashi. “Ratchi ‘kyoko ronsha’ no musekinin.” Newsweek, 24 October 2012, p.32.

46 See here (accessed 7 April 7, 2013).

47 A recent description of Chongryun’s network in Japan is provided Armin Rosen’s article “The Strange Rise and Fall of North Korea’s Business Empire in Japan” published in The Atlantic, 26 July 2012 (accessed 7 April 7, 2013).

48 See here (accessed 30 March 2013).

49 See here (accessed 30 March 2013).

50 See “Kyūshinryoku modaranu chōsen soren jijitsujo no ‘taishikan’ baikyaku kyogaku shakkin ni ikari funshutsu.” Asahi Shimbun (3 April 2013), p.10.

51 See here (accessed 29 March 2013).

52 See here (accessed 29 March 2013).

53 See here (accessed 8 April 2013).

54 Ibid.

55 See here (accessed 8 April 2013).

56 See here (accessed 11 April 2013).

57 See here (accessed 30 March 2013).

58 See here (accessed 11 April 2013).

59 For the full transcript of the speech see here (accessed 8 April 2013).

60 Araki is also director of the so-called Investigation Commission on Missing Japanese Probably Related to North Korea (Tokutei shissōsha mondai chōsakai, nicknamed Chōsakai). Chōsakai is closely linked to the Sukuukai and operates in many ways as a “research body” for the abduction lobby.

61 See here (accessed 8 April 2013). High academic reputation for DPRK expertise can only be credited to Takesada Hideshi, formerly of Yonsei University and Shizuoka Prefectural University’s Izumi Hajime, both prominent DPRK specialists.

62 For a detailed account on DPRK-China relations see Gomi Yōji’s Kitachōsen to chūgoku: dasan de tsunagaru dōmeikoku wa shototsu suru ka (Tokyo: Chikuma shinsho, 2012).