Key words: Korean cinema, film production, film policy, Park Chung Hee, Shin Sang-ok

After censorship was eliminated in 1996, a new breed of writer-directors created a canon of internationally provocative and visually stunning genre-bending hit films, and new and established producers infused unprecedented venture capital into the local industry. Today, a bevy of key producers, including vertically integrated Korean conglomerates, maintain dominance over the film industry while engaging in a variety of relatively near-transparent domestic and international expansion strategies. Backing hits at home as well as collaborating with filmmakers in China and Hollywood have become priorities. In stark contrast to the way in which the film business is conducted today is Korean cinema’s Golden Age of the 1960s – an important but little-known period of rapid industrialization, high productivity and clandestine practices. To develop a fuller understanding of the development of Korean cinema, this article investigates the complex interplay between film policy and production during the 1960s under authoritarian President Park Chung Hee, whose government’s unfolding censorship regime forced film producers to develop a range of survival strategies. A small but powerful cartel of producers formed alliances with a larger cohort of quasi-illegal independent producers, thus – against all the odds – enabling Korean cinema to achieve a golden age of productivity. An analysis of the tactics adopted by the industry reveals the ways in which producers negotiated policy demands and contributed to an industry “boom” – the likes of which were not seen again until the late 1990s.

Power of the Producer

Since the early 1990s, Korean film producers have been shaping the local film industry in a variety of ways that diverge from those followed in the past. A slew of savvy producers and large production companies have aimed to produce domestic hits as well as films for and with Hollywood, China, and beyond, thus leading the industry to scale new heights.2 They differ markedly from those producers and companies that, throughout the 1970s and 1980s, were primarily focused on profiting from the importation, distribution and exhibition of Hollywood blockbusters and Hong Kong martial arts films in Korea. From the 1990s, Korean cinema benefitted from a comparatively new level of transparency and efficiency that family-run conglomerates (chaebols in Korean) and other financial institutions brought to the local film industry after they began to see the film business as a good investment – despite the impact of the 1997-98 Asian economic crisis.

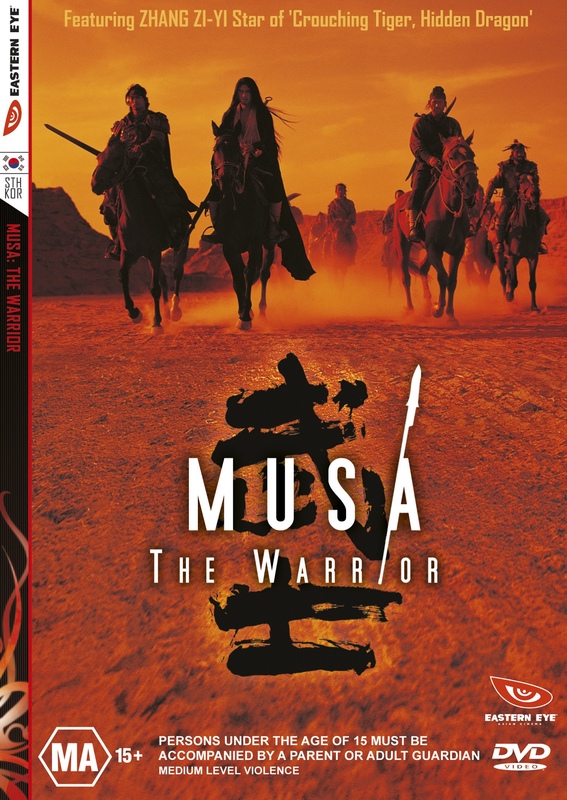

For instance, in 2001, representative producer Tcha Seung-jai – founder of Sidus Pictures (now SidusFNH) and former chairman of the Korea Film Producers’ Association – opened an important pathway between the Korean and Chinese film industries when he and writer-director Kim Sung-soo shot the historical epic Musa The Warrior (2001: see Figure 1) as a co-production in Northeast China. Musa was the most expensive Korean film budgeted at the time, thus establishing Tcha’s reputation as one of Korea’s most powerful and ambitious producers in Chungmuro – the centre of Korea’s film industry.3 In 2006 and again in 2007, Tcha was selected by his professional colleagues as the most influential person in the industry, acknowledging his management of genre hits such as Girls’ Night Out (1998), Save the Green Planet (2003), Memories of Murder (2003), and A Dirty Carnival (2006), as well as his mentoring of countless junior staff who are now working at the center of the industry.4

However, a significant part of the producer mix today is the vertically integrated group of investor-distributors CJ Entertainment and Lotte Entertainment, that is, powerful corporate executive producers who now monopolize all aspects of the industry. They have more or less cut traditional producers like Tcha out by forming their own relationships with bigger directors. As a result of their size, exhibition chains, and ties to the corporate media and financial institutions, together these executive producers have successfully exerted more influence than any single producer. The group’s power and position was considerably enhanced after they resuscitated the industry following the recession it underwent in 2006 thanks to illegal downloading and piracy, and a succession of unsuccessful films. This was at a time when the power of individual producers such as Tcha, and others such as Lee Choon-yun (Cine2000), Jaime Shim (Myung Film), Oh Jung-wan (bom Film), and Shin Chul (Shin Cine), had begun to wane, partly due to a decline in investor confidence caused by the loss of international pre-sales and the erosion of ancillary markets. Also, several of these traditional producers were hit hard by their poor decisions to list their companies on the stock market through backdoor means. CJ Entertainment, which launched its China branch in mid-2012, now leads the pack with its corporate production, distribution and sales, and actor management services, as well as an increasing number of multiplex cinemas in Korea and a smaller number in China (all operating under the brand-name CGV).5

These corporate/executive producers have ushered in a new level of ruthless efficiency in the film business by maintaining and fine-tuning proven pre-production and marketing planning techniques – core elements of “high-concept” filmmaking. In turn, their efforts have genereted increased venture capital and also ensured accountability to their shareholders and audiences rather than pandering to the whims of auteur filmmakers. Their diverse business strategies and achievements have mediated the risks associated with previous financial strategies involving self or family funding, private loans, and pre-sales from regional distributors/exhibitors, thus redirecting the impetus of the industry in new directions. In sum, the so-called power of the producer – as opposed to the power of writer-directors such as Im Sang-soo, Kim Jee-woon, Hur Jin-ho, Lee Chang-dong, Park Chan-wook, Bong Joon-ho, and Kim Ki-duk – has reached new heights in Korea during the 2000s by their willingness to finance globally marketable films and encourage talented young directors to make them.

The power behind the corporate producer has become even more evident with the recent news that producers JK Film (in conjunction with CJ Entertainment) had fired auteur Lee Myung-se – the acclaimed writer-director of notable films such as M (2007), Duelist (2005), Nowhere to Hide (1999), and Gagman (1989) – mid-stream from the 2012 production of the spy-comedy Mister K. According to industry sources, JK Film and Lee had divergent views on artistic and legal issues.6 Lee was replaced with rookie director Lee Seung-joon (who had assisted on the blockbuster films Haeundae/Tidal Wave (2009) and Quick (2011)), thus sending a clear message about the limits of artistic freedom that corporate producers are willing to extend to a director.7

With the increasing power of the producer in the contemporary Korean cinema in mind, this article focuses on a very different but pivotal period when a range of dynamic production strategies – including creative responses by filmmakers to government policy – contributed to an industry “boom” in the 1960s. Given the significant impact of this period of rapid industrialization on this past decade, it is surprising how little attention it has been given in previous studies.

Earlier studies highlight the frenzy of production during the 1960s, paying tribute to the rise of auteur directors and the memorable films they made.8 This was a period when Korea experienced rapid progress in industrialization and policy development, as well as in the production of entertainment for the masses. A large number of productions that stemmed from a seemingly limitless source of creative energy focused the spotlight on a coterie of passionate filmmakers and their artistic achievements. Although these historiographical studies provide extensive details about the formation of the nation’s cinema in artistic terms, they are less successful in providing an adequate political-economic perspective on the industry as a whole. They obfuscate information about the dodges and occasional acts of resistance engaged in by producers and others further down the industry food chain. By contrast, close attention to the often seamless connections between policy and industrial and artistic factors will prove to be the key to understanding how this cinematic golden age was built and buttressed.

Perhaps even more surprising is the near-complete omission of cultural policy and the development of South Korea’s creative and cultural industries in more recent scholarship on Park Chung Hee.9 Despite the enormous amount of information available, these studies lack a sustained discussion of the central roles that film and media played in the government’s well-documented national industrialization strategy and policy.10 In some ways, the present article is the missing chapter in the Park Chung-hee story.

Hypergrowth of the Propaganda Factory

On 16 May 1961, General Park Chung Hee led a military coup that successfully seized control of South Korea. Within the first few months of its abrupt rise to power, his military government had succeeded in systematizing its near-total administrative control over all film production, distribution (importing and exporting), and exhibition. This process began with the creation of the Ministry of Public Information (MPI) on 20 May 1961, the National Film Production Centre (NFPC) on 22 June 1961, and the Motion Picture Law (MPL) on 20 January 1962. The MPI was tasked with the role of administering the NFPC and the MPL, and coordinating all film, print and radio broadcasting media campaigns.

Almost immediately, the film industry, which was experiencing a new-found creativity since the end of the Japanese colonial period (1910-1945) with accomplished artfilms such as Yu Hyun-mok’s Obaltan/Aimless Bullet (1960; see Figure 2), was reduced – both literally and figuratively – to the status of a propaganda factory in which all productions were classed as either “hard” or “soft” propaganda. They were to become key tools in what one critic described as “campaigns of assault” and “campaigns of assistance” respectively.11 The regime achieved these aims first by consolidating the number of feature film production companies from 76 to 16 in 1961 and then by launching two new initiatives.

The first was the National Film Production Center (NFPC), established in June 1961 to produce newsreels and cultural films (munhwa yeonghwa, documentary or narrative films delivering specific political messages), and to distribute these materials through commercial cinemas. The NFPC grew out of the Film Department of the Bureau of Public Information (BPI) that had been established in 1948 under the Syngman Rhee government (1948-1960).

The second initiative was the Motion Picture Law (MPL), which guided the production of propaganda feature films with a heavy hand. The MPL conveniently adopted the oppressive contents of the Chosun Film Law such as production control, the import quota system, script censorship, and the producer registration scheme outlined in 1941 by the Japanese colonial government in Korea, applying them on a wide scale in order to control Korea’s burgeoning film industry.12 All these developments and precedents worked hand-in-hand to control the film industry. The government’s ultimate intention was to construct a studio system that operated in similar ways to Hollywood studios, but with an authoritarian twist.

In January 1962, the military government promulgated its first film policy through the MPL, imposing twenty-two wide-ranging measures relating to censorship fees, screening permits, producer registration, and importing, exporting and exhibiting films. These measures applied to the entire Korean film industry, with heavy fines or imprisonment for non-compliance.13 The MPL consisted of three main components: the Producer Registration System (hereafter PRS), import regulations and censorship guidelines. Relentless enforcement of these three elements enabled the MPI to effectively control the film industry (particularly producers) by means of a system of “carrots on sticks”.14

Through the PRS, the government compelled all producers, including those remaining following the forced consolidation in 1961 and others interested in joining this elite group, to register with the MPI. According to the MPL, each applicant for registration had to meet specific criteria for equipment and personnel: ownership of a 35mm film camera and 50 KW lighting kits, as well as securing contracts with at least one experienced engineer or technical expert and two actors with established careers. Following the introduction of the law, these relatively liberal requirements enabled all 16 of the consolidated producers, plus an additional five that also met the criteria, to register under the new system.

However, in 1963 amendments to the MPL introduced stricter criteria, making it tougher for Korea’s 21 existing producers to maintain their registration status. Each registered producer was now obligated to operate a permanent studio (approximately 7,100 sq feet in size) equipped with three 35mm film cameras, 200 KW lighting kits, and a sound recorder. Contracts with three directors, three cinematographers, one recording engineer, and ten actors per studio also became mandatory, requirements which in turn gave registered producers control over directors, actors, and other technicians. Additionally, each company was required to maintain a rigorous production schedule of 15 films per year and to engage in the import and export of films.

This forced merger between its production and distribution arms consolidated the industry even further. Almost overnight, a “studio system” resembling a factory assembly line had been born. Korea now had six major film companies – a cartel – that suddenly found themselves in possession of exclusive privileges. The financial power and charismatic authority of those in the inner circle increased over time as they became the heart and foundation of all industry activities.

There were three types of registered (i.e. authorized) producers operating during the 1960s: producers in the traditional sense; producers with an importing background; and short-term producers.15 Those in the first group, such as Shin Film, Geukdong, Hapdong, Taechang, and Hanyang, followed the original agenda of the PRS to the letter, treating production as their primary business and film importing as a sideline.

The second group, represented by Hanguk Yesul and Segi Sangsa, which had begun their import businesses as far back as 1953, prioritized importing over production. Under the PRS, they had to transform themselves into producers to preserve their professional status. Due to their limited production expertise, the firms in this group relied heavily on working with independent producers by illegally subcontracting and selling production rights to them.

The third group consisted of smaller registered producers including Shinchang, Aseong and Daeyoung; although they managed to become members of the Korean Motion Picture Producers Association, they failed to maintain their registered status as government requirements became tougher. Their core business was working with the independent producers and administering the necessary paperwork for making films. This type of registered producer was often described as “a real estate agency”.16

Rise of the Cartel and the Coalition of the Willing

The systematization of the PRS threw up a cartel of producers, who operated from the industry’s center. Within this elitist system, registered producers maintained direct lines of communication with the MPI and other industry participants. Contributing covertly to the industry’s productivity was a slew of unauthorized independent producers and importers who were more than willing to help the cartel manage their demanding workloads, in particular their ever-increasing registration requirements. A small army of exhibitors, operating across Korea’s 13 separate provinces, enabled these various practitioners – both elite and “illegal” – to keep the industry afloat by investing in productions through pre-sales.

Film financing was largely sourced from savvy exhibitors who invested in a production in return for the exclusive rights to distribute and screen the film across multiple provinces. Competition was fierce, as by law only six prints of a given film were allowed to circulate nationwide.17 Ji Deok-yeong and Kim Dong-jun, owners of the Seoul-based Myeongbo Cinema and Paramount Cinema respectively, and alternate presidents of the Korean Theatre Association throughout the 1960s, between them represented the interests of exhibitors, who reached a nationwide total of 597 in 1969.18

In this way, demand from regional exhibitors stimulated producers to increase the size and frequency of their output. Usually, exhibitors advanced about 60% of the production budget to producers in exchange for exclusive rights – paying up to a further 30% on receiving the film print.19 Buffered by this economically reciprocal funding scheme, producers were exposed to very little risk.20 In addition, in some cases producers were able to secure pre-sales funding in excess of the total production budget, in which case the excess went straight into their coffers.21

Exhibitor-investors also influenced the production environment in similar ways to the impact of “New York Bankers” in Hollywood – at least as it was understood at the time.22 Ultimately, producers became overly dependent on pre-sales investments, and thus failed to develop a range of other funding sources. This exposed the industry to being unduly influenced by exhibitors in making decisions about favored film genres and styles.23 By the late 1960s, the film market was oversupplied with product, mostly quota quickies – “cheap second-rate domestic films”.24 Faced with this flush of lower quality films, exhibitors had difficulty earning high yields on their investments. This situation was exacerbated by the fact that exhibitors began passing bad cheques to producers.25 As a result, the flow of funding for productions came to an abrupt halt, resulting in an unprecedented downturn for the industry.26 Today, producers run the film industry with far greater transparency and accountability than was the case in the 1960s.

There were two major industry organizations operating at this time: the KMPPA (Korean Motion Pictures Producers Association), which became a powerful trade association that advanced the business interests of its members – the cartel of registered producers; and the MPAK (Motion Picture Association of Korea), which represented the remaining members of the industry.27 Although there was no ceiling set for membership of the KMPPA, the MPI controlled the organization’s size by making frequent changes to the PRS which kept the number of registered producers at a small but optimal level, resulting in constantly fluctuating numbers.

Most previous scholarship has viewed the introduction of the PRS as part of the Park government’s larger industrialization agenda, and has seen the compulsory nature of the scheme as a harmful influence on the industry.28 By contrast, other studies have linked the development of the PRS to the Hollywood studio system, showing how a small number of registered producers such as Hanguk Yesul and Donga Heungeop attempted to mimic Hollywood’s practice of vertical integration – despite their ultimate failure due to lack of capital and a disorganized distribution system.29 Both views offer food for thought.

In the US in the 1940s, a group of elite studio owners ran their Hollywood studios as “a system of corporations”,30 asserting their (business-oriented) “creative control and administrative authority”31 over filmmaking. Similarly the PRS model concentrated power among a small cartel of producers, and the KMPPA operated as an oligopoly similar to the US trade association, the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA). However, in Korea, although producers had the right to distribute films, in effect exhibitors had much more say over the distribution process – that is, over the choice of films for public screening and their exhibition venues. Producers had to deal with at least six exhibitors when making decisions about the distribution of a particular film. These practical constraints illustrate the vulnerability and political impotence experienced by the Korean film industry under the authoritarian military regime of the 1960s. While the Hollywood studio system allowed major studios such as Fox Film Corporation, Paramount Pictures, Universal Pictures and Columbia Pictures (all controlling members of the MPAA) to control the bulk of the US market, the KMPPA (and PRS) remained a much less stable and predictable entity than the MPAA.

Once more, the cartel or oligopoly that emerged out of the PRS was a mixture of two models: the family-business-oriented chaebol and the Hollywood studio system. The chaebol concept grew out of Japan’s prewar zaibatsu system, which enabled a few large family-run vertically integrated business conglomerates – in the automobile, iron/steel, and heavy chemicals industries, for instance – to exert a significant influence on the nation’s economy.32 Resembling the chaebol, but on a much smaller scale, the PRS overemphasized the role of production, which was a direct outcome of developmental state policy.33 Buttressing the film industry in this way reflected the ways in which Park “mixed the Japanese ethos of top-down mobilization and the US ideas of technocracy with Korean nationalism in most un-Japanese and un-American ways to clear the way for economic growth”.34

Through the PRS, and comparable to initiatives launched by other countries such as Britain, Japan, India, and China, the Korean government attempted to build a national film studio system based on current industry practices in the US. As a spokesperson for the KMPPA, producer/director Shin Sang-ok strongly advocated the benefits of industrialization, seeking to influence amendments to the MPL that would enable his own production company, Shin Film, to function more like Columbia Pictures. While Shin may have referred to Columbia Pictures as the kind of studio he wished to create, he also learned how Japanese film studios operated while forming relationships with two of them, Daiei and Toho.35 In the process, it became clear to Shin that the Japanese film industry was built on the Hollywood studio system.

For its part, the Park regime may have had at least one eye on the Japanese film industry, which had been thriving in both domestic and overseas markets since the 1950s. Under his government’s direction, the studio system in Korea flourished – despite the weakening of the studio system in Hollywood and Japan during the 1960s. This late adoption of the studio system facilitated the government’s control over the industry because studios had to work within its directives in order to keep in business. At the time, the efforts of Shin and the Korean government were recognized in US trade reports that considered the stage of development reached by the Korean film industry as “comparable to early Hollywood, with players under contract to the various studios”.36

Despite some similarities between the structure of Korea’s PRS and the major studio system in Hollywood (a “mature oligopoly – a group of companies cooperating to control a certain market”,37) the effects of centralized policy intervention in Korea – and the resultant artificial shaping of the industry’s development – made the Korean system very different from Hollywood. In particular, given that the PRS had been designed as a production-centric industry system, the neglect of exhibition and distribution became a serious barrier to vertical integration.

Taming Producers with “Carrots on a Stick”

Throughout the 1960s, the PRS served as the key mechanism for shaping and controlling the film industry. Registration status was kept current by members meeting the new criteria announced with each policy modification. Producers seemed to be constantly catching up with these ever-changing requirements, giving rise to the oft-used metaphor of a carrot on a stick. Striving to strike a realistic balance between profit-taking and policy demands, registered producers engaged in three key strategies: trading rights to produce a film (daemyeong jejak in Korean); trading rights to import a film (under the Import License Reward System, discussed below); and generating film pre-sales.

By continually introducing new industry specifications, the MPI was able to influence (and elevate) industry standards while regulating the number of producers and the day-to-day conduct of their activities. However, as discussed below, the MPI’s influence in such matters was only partially effective, as a surprising number of unregistered (aka independent) producers found ways to circumvent the system. This was a relatively easy task given the industry’s small size and collegiality; almost everyone knew everyone else.

Daemyeong jejak (hereafter daemyeong) was a widespread subcontracting system that emerged at the end of 1961. It enabled a registered producer to remain competitive by meeting stringent registration requirements while simultaneously facilitating – theoretically illegal – filmmaking opportunities for independent producers (deemed illegal after the PRS was launched in 1962). Subcontracting of this kind involved a four-step process.

First, in a move beneficial to both parties, a registered producer gave (and later sold) independent producers the right to make films by letting them use his name (registered status) in order to file the necessary paperwork and to get approval for production. Second, the independent producers – who included names such as Ho Hyeon-chan and Choi Hyeon-min, and directors Yu Hyun-mok and Jeong So-yeong – made their films using their own or the registered producer’s networks and equipment, opening the way to substantial box office profits without the large investment necessary for official registration. 38

Third, from 1963 the independent producer would return the favor by paying a commission to the registered producer, and the film’s box office profits would go into the former’s pockets.39 When a daemyeong film was screened, the opening credits identified two types of producers: the producer-in-charge (jejak damdang or chong jihwi, referring to the independent producer) and the producer (jejak, referring to the registered producer). This acknowledgement suggested that the practice, albeit illegal, was widespread and recognized by those involved in the industry. Finally, the film in question was submitted to the MPI’s film awards process, an arrangement which exclusively benefitted the registered producer if successful as the “prize” was a license to import and distribute a foreign film – a sure formula for generating lucrative box office returns.

Whilst this semi-covert activity – initially conducted without the exchange of money – was an unintended consequence of the PRS and therefore fell outside the government’s blueprint for the industry, it became critical to the sustainability of the producers’ cartel and the industry as a whole. In 1963, the rate of daemyeong-funded productions increased rapidly after amendments to the MPL required registered producers to make a minimum of fifteen films per year. Simply put, it was a valuable tool that enabled registered producers to meet the increasing demands of the PRS. Eventually, the daemyeong system became so entrenched that the MPI acquiesced in its operation, demonstrating how at least those filmmakers with the right networks persevered by following multiple pathways for survival and success under the Park regime.

As part of this changing environment, in 1964 the MPAK increased the level of its complaints against registered producers exploiting their independent colleagues.40 Despite this, the daemyeong system continued to grow. Trade reports estimate that, in 1965, 130 out of 189 new films were daemyeong productions, meaning that two-thirds of all films produced in Korea at this time were completed by “dubious” means.41 In reality, these figures indicated that few if any registered producers had been able to produce the statutory minimum of fifteen films per year that the MPL required.42 The MPI did not hinder daemyeong because the practice was clearly beneficial in enabling the industry to reach a desired level of productivity, rising rapidly from 86 films in 1961 to 189 in 1965.43

However, the end of the system was not far away. In 1966, the same year that Korea’s screen quota was launched, the MPI formally banned daemyeong because it was no longer needed as a mechanism for generating productivity. The government was satisfied with current levels of productivity, and set an annual production figure for the industry of 120 films – a target easily achievable by the registered producers alone. Nevertheless, daemyeong continued, but with escalating costs for independent producers as a result of the lower number of productions permitted.44 Few unregistered producers could afford to stay in the game, and a handful even took their own lives out of a growing sense of despair.45

In response to ongoing organized protests over the new production regime, the KMPPA agreed to eliminate the annual quota limit and daemyeong was legalized by the MPI.46 In responses, production numbers soared from 172 in 1967 to 229 in 1969.47

About 80% of the films produced in 1971 were daemyeong films, mostly low quality “quota quickies,” and all 21 registered producers were involved in daemyeong productions, with a maximum of eight films each, reaffirming the widespread utilization of the system.48 Ironically, the government’s acceptance of the industry’s call for loosening of controls undermined the production environment, eventually leading to a dark age (throughout the 1970s) for Korean cinema.

Cinema of Deterrence

To further regulate the industry, the MPI enacted two related measures in 1962 which were aimed at deterring the number of film imports entering Korea and restricting their exhibition: the Import Recommendation System (IRS) and the Import License Reward System (ILRS). These two schemes were used alongside the Screen Quota System, which the MPI introduced in 1966, to curtail the powerful influence that foreign films were commanding at the box office.49 Given that the majority of foreign feature films exhibited at this time were American, Hollywood distributors were effected the most by this policy.

The IRS required importers to submit a list of films to the MPI for approval. During this process, content regulation was carried out on two fronts: firstly, through the self-censorship imposed by the importers themselves and secondly, through the MPI’s screening process of potential films for import. The chief criterion used by the MPI was a moral and cultural one – whether a particular film would be harmful or offensive to Korea’s customs and manners.

Linked to the IRS, which served as the government’s primary import control tool, the ILRS functioned as a financial subsidy for the registered producers. The system was designed to administer licenses based on five criteria: quantity of films produced; quality of production; the existence of a successful export contract; formal co-production status; and submissions to international film festivals and awards received. Each time a producer met any one of these criteria he was eligible to receive a license to import one film.50

In response, registered producers devised two covert ways of obtaining import licenses and/or exploiting them for profit: firstly, by falsifying or faking official documents such as domestic film export licenses and international co-production contracts; and secondly, by selling an import license to another registered producer. From early on, producers freely engaged in these two illegal and so-called black market strategies. The idea of selling import rights was especially appealing to those registered producers who were prolific filmmakers and/or frequent recipients of foreign film festival nominations and awards, but who were unfamiliar with the import/export side of the business.51

Spurred by the big profits to be made, illegal import agencies became very active, purchasing import licenses from registered producers for 3 to 6 million won (between approximately USD$23,000 and USD$46,000) each and then negotiating with American film distributors (based in Japan) on their behalf.52

In most cases, export prices for a single film varied between about US$5,000 and US$10,000, including royalty and printmaking fees.53 In other cases, however, films were exported for as little as $100 in order to generate the necessary paperwork that would enable a registered producer to receive an import license.54 While the falsification of export figures was on the rise throughout the 1960s, the MPI took little action to curtail the process because it lacked the resources to monitor activities that were happening on such a large scale.

With the rising popularity of the martial arts genre after the mid-1960s, there was strong competition among registered producers to import Hong Kong films. They were significantly cheaper than Hollywood films and performed equally well at the box office. One of the easiest ways to import a Hong Kong film was by informing the MPI that the film in question was a Korean–Hong Kong co-production. Apparently, Hong Kong production houses such as the Shaw Brothers willingly agreed to assist Korean producers by forging co-production contracts, even though these deals involved the selling of their films to Korea.55 The practice of faking international co-production contracts lasted until the early 1980s.56 Sometimes, a short scene with a random Korean actor was inserted into a film, as in the Shaw Brothers’ Monkey Goes West (1966) and Valley of the Fangs (1970) – in order to give some semblance of a co-production.

In short, registered producers resorted to a variety of tricks and schemes to obtain import licenses, especially as the ability to import Hollywood films brought with it the opportunity for lucrative box-office takings and increased profits for production-distribution companies. The producers, or importers working on their behalf, contacted Hollywood agencies based in Japan such as Warner Brothers and negotiated the films to be imported as well as prices; such deals usually included a two-year distribution period, royalties, and expenses for prints and freight.57

In 1968, 18 Korean import agencies including Donga Export Corporation, Hwacheon Corporation and Samyeong handled around 90% of foreign film imports (about 50 films out of 60).58 Although the number of domestic films exhibited in Korea outnumbered foreign films at this time, foreign productions consistently drew larger audiences.

By the mid-1960s, foreign films, which were exhibited for two or three times as long as Korean films, were outperforming domestic films at the box office on a regular basis.59 A new generation of young filmgoers born after the end of the Japanese colonial era in 1945 believed that the narrative and aesthetic qualities of foreign films were superior to the local product.60 Hong Kong martial arts films, “spaghetti” westerns and James Bond action films were especially popular with this group, generating much larger profits than ever before. For example, although the number of foreign and domestic films screened in 1968 in Seoul was 80 and 204 respectively, the audiences for foreign films left local films in the shade: in that year the average audience for foreign and domestic films reached 107,269 and 40,271 respectively.61

This two-headed import policy substantially subsidized the industry. At the same time, it encouraged registered producers to follow government guidelines as though they were chasing a carrot on a stick.

In less than five years, the MPI’s PRS, censorship guidelines, and import regulations enabled the Park government to shape and control the film industry as it had done for the automobile and iron and steel industries.62 The Park government wielded increasing power over the film industry, seeing the potential of cinema as an important vehicle for disseminating national ideology as it did in these other industries. Preventing the exhibition of noncompliant films was a key aspect of film policy during Park’s tenure as president, thus completing the harnessing of film production, distribution and exhibition to his political agenda as a propaganda tool.

Despite the draconian structure created by the MPI’s three main policy components, throughout the Park period members of the film industry – in particular the Motion Picture Association of Korea, representing those operatives not covered by the registered producers’ body, the Korean Motion Picture Producers Association – offered resistance wherever and whenever they could. On behalf of the great majority of the film community – including directors, cinematographers, actors, and independent (unregistered) producers – the MPAK consistently lobbied for the abolition of the MPL. In particular, it challenged the MPI over the PRS and daemyeong processes by appealing to the National Assembly as early as March 1964, on the grounds that daemyeong strengthened the privileged cartel of registered producers. The anti-MPL campaign was a bold sign of the industry’s readiness to stand up to bullying from the MPI (and the Park government more generally), and resistance spearheaded by the MPAK continued sporadically throughout the 1960s.

Conclusion

The golden age of cinema in Hollywood (1929-1945) has been defined as a period marked by exceptional films, and the time when sound film was perfected as an “influential business, cultural product and art form”.63 Similarly, the golden age of French cinema in the 1930s has been characterized as the age of production, auteurs, star actors, and the use of literary texts for filmmaking.64 According to these critiques, the term “golden age” refers to a period when cinema reaches the point of being appreciated as the combined product of art, business and technology. The same notion can readily be applied to Korea’s golden age of cinema in the 1960s, a time when the film industry underwent rapid industrialization under the Park Chung Hee dictatorship, raised production values, and experienced the advent of new auteurs and their works. Yet, at the crux of this development was a cartel of powerful producers, whose various business models shaped and sustained the film industry.

During the Golden Age of the 1960s, Korean cinema was largely defined by dynamic power struggles which brought the government and the film industry together in often conflictual ways as producers, both registered and independent, sought to assert some measure of independence for themselves and the industry as a whole. Today, while some of the business strategies adopted by 1960s filmmakers may seem absurd and retrogressive, we can see that they were responding to specific problems and that their solutions were effective at the time. Their desire to achieve and retain their status as producers provided a dynamic motivation that gave a powerful impetus to the film industry as a whole. Money and the promise of prosperity drove productivity, allowing the local industry to enjoy its first true golden age.

By examining this early golden age of Korean cinema from a political-economic angle, the authors have attempted to provide a more complex discussion of national cinema and its links to policy and the production side of the industry than has previously been achieved. One of the central claims of this study is that the golden age of the 1960s was the outcome of a combination of a protectionist film policy and state control, and the new production system that resulted from these circumstances.

Under the direction of Park Chung Hee’s military regime, the MPI achieved near-total administrative control over production, exhibition, import and export activities with the aim of converting the film industry into a propaganda factory. The Ministry engaged in two types of overt propaganda – a two-pronged weapon consisting of the direct propaganda produced by the NFPC, composed of newsreels and short message films, and the more oblique material produced by the private film industry such as anticommunist and ideologically driven (“enlightenment”) feature films, all directed by the exigencies of the MPL. While a range of contemporary Korean filmmakers continues to make films dealing with cultural patriotism and national issues, the use of “propaganda” is infinitely more subtle than in the past.

In the 1960s, some important differences existed between Korea’s PRS and the Hollywood studio system. In Korea, the studio system was created by the state. Following the regime’s emphasis on productivity, the PRS was designed to create a production-centric industry system, neglecting exhibition and distribution, and thus vertical integration in any real sense was obstructed – a significant deficit in the industrial development model proposed by an authoritarian military regime.

Hence, the policy framework and interventions put in place by the Park regime were never totally effective or successful. In response to these government moves, the industry developed various coping mechanisms and reactive strategies, such as sharing equipment and staff when being inspected for compliance with infrastructure criteria. While the industry grew in size as a result of the PRS system, its heavy focus on the production arm led to the relative neglect of other areas such as distribution and exhibition, leading to unbalanced development. Producers devised various less-than-transparent methods for dealing with the pressures they faced, creating a daemyeong system and exploiting the ILRS. These back-door deals and black market ties have been left far behind in 2000s, as the industry has become increasingly transparent and efficient, especially in financial matters, and has suffered less intervention from the government – especially since the Kim Dae-jung (1998-2003) administration’s adoption of the principle of “support without control”.

The rise of an elite producers cartel and the systematization of their operating methods in the 1960s was partly a by-product of the Park regime’s policy of supporting chaebols – family-run business conglomerates. Both the PRS and chaebols were products of a developmentalist state policy. In favoring chaebols, Park and his followers selected and nurtured industrial elites based on factors such as personal connections and proven records of business performance. In return, the chaebols spearheaded the government’s export drive, which was also a critical part of the production side of the industry. However, while the film industry shares many similarities with chaebols in terms of its development pattern, there are also differences between them: chaebols still continue to operate in Korea, while the PRS disappeared in the 1980s. The chaebols and their legacy have survived for three main reasons: the government became overly dependent on them for economic reasons; the chaebols by contrast became progressively less dependent on the government; and their leaders remained in their posts while political regimes changed around them.65

The PRS was eventually abolished in 1984, when anyone became free to open a production company by reporting their intentions to the Ministry of Culture and Athletics (now called the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism). Then in the late 1990s and early 2000s – within the country’s developed market economy system – two major companies were responsible for the first sustained attempt at vertical integration within the Korean film industry: CJ Entertainment and Lotte Entertainment. Without the threat of government intervention hanging over them, the influence of these three companies increased rapidly. As the center of private funding for the industry, and covering all three key areas (production, distribution and exhibition), this major new conglomerate is continuing to stimulate the growth of a stronger and more powerful “studio system” in Korea.

Ae-Gyung Shim has contributed to several Korean and Australian film industry writing projects, and has held research assistant and part-time teaching positions at the University of Wollongong. Her Routledge book Korea’s Occupied Cinemas, 1893–1948 (with Brian Yecies) was published in 2011. Dr Shim is a past Korea Foundation Post-Doctoral fellow hosted by the Centre for Asia Pacific Social Transformation Studies (CAPSTRANS) at the University of Wollongong. Contact details: Institute for Social Transformation Research (ISTR), University of Wollongong, Wollongong, NSW 2522, Australia. E-mail: [email protected]

Brian Yecies is a Senior Lecturer in Media and Cultural Studies at the University of Wollongong, and an associate member of the Institute for Social Transformation Research (ISTR). He teaches transnational film and digital media subjects that emphasize culture, policy and convergence in Asia. Dr Yecies is a past Korea Foundation Research Fellow and a recipient of prestigious grants from the Academy of Korean Studies, Asia Research Fund and Australia-Korea Foundation. His Routledge book Korea’s Occupied Cinemas, 1893–1948 (with Ae-Gyung Shim) was published in mid-2011. Contact details: Faculty of Arts, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, NSW 2522, Australia. E-mail: [email protected]

Recommended citation: Ae-Gyung Shim and Brian Yecies, ‘Power of the Korean Film Producer: Park Chung Hee’s Forgotten Film Cartel of the 1960s Golden Decade and its Legacy,’ The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol 10, Issue 52, No. 3, December 24, 2012.

Articles on related subjects

• Sonia Ryang, North Koreans in South Korea: In Search of Their Humanity

• Robert Y Eng, China-Korea Culture Wars and National Myths: TV Dramas as Battleground

• Brian Yecies and Ae-Gyung Shim, Disarming Japan’s Cannons with Hollywood’s Cameras: Cinema in Korea Under U.S. Occupation, 1945-1948

• Ch’oe Yun and Mark Morris, South Korea’s Kwangju Uprising: Fiction and Film

• Mark Morris, The New Korean Cinema, Kwangju and the Art of Political Violence

• Stephen Epstein, The Axis of Vaudeville: Images of North Korea in South Korean Pop Culture

• Mark Morris, The Political Economics of Patriotism: Korean Cinema, Japan and the Case of Hanbando

References

Ahn, Ji-hye. “Film Policy after the 5th Revision of the Motion Picture Law: 1985-2002 (Je 5-

Cha Yeonghwa-Beop Gaejeong Ihu-Ui Yeonghwa Jeongchaek: 1985-2002).” In A History of

Korean Film Policy (Hanguk Yeonghwa Jeongchaeksa), Seoul: Nanam Publishing, 2005.

Bergfelder, Tim, Sue Harris, and Sarah Street. Film Architecture and the Transnational Imagination: Set Design in 1930s European Cinema. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2007.

Byon, Jae-ran. “Film (Yeonghwa).” In Korean Modern Art History Iii: 1960s (Hanguk

Hyeondae Yesulsa Daegye Iii: 1960 Nyeondae), edited by The Korean National Research

Center for Arts, 187-244. Seoul: Sigongsa, 2001.

Cho, Young-jung. “From Golden Age to Dark Age, a Brief History of Korean Co-

Production.” In Rediscovering Asian Cinema Network: The Decades of Co-Production

Between Korea and Hong Kong, 14-24. Pusan: Pusan International Film Festival, 2004.

Chung, Kae H, Hak-chong Yi, and Jung Ku H. Korean Management: Global Strategy and

Cultural Transformation. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1997.

Cumings, Bruce. Korea’s Place in the Sun: A Modern History. New York: W.W.

Norton & Company, 1997.

Gomery, Douglas. The Hollywood Studio System: A History. London: British Film

Institute, 2005.

Ho, Hyun-chan. 100 Years of Korean Cinema (Hanguk Yeonghwa 100 Nyeon). Seoul:

Moonhak Sasang Press, 2000.

Jewell, Richard B. The Golden Age of Cinema: Hollywood, 1929–1945. Malden: Blackwell, 2007.

Kim, Byung-Kook and Ezra F. Vogel, eds. The Park Chung Hee Era: The Transformation of South Korea. Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press, 2011.

Kim, Hong-dong. “Reading policy through development of film regulations (yeonghwa

beopgyuwa sichaek-euro bon jeongchaek-ui heureum).” In Current Flow and Prospects of

Korean Film Policy (hanguk yeonghwa jeongchaek-ui heureumgwa saeroun jeonmang).

Seoul: Jimmundang Press, 1994.

Kim, Hyung-A. Korea’s Development Under Park Chung-Hee: Rapid Industrialization 1961-

1979. New York: RoutledgeCurzon, 2004.

Kim, Hyung-A and Clark W. Sorensen, eds. Reassessing The Park Chung Hee Era, 1961-1979. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2011.

Kim, Mee-hyun, Chung Chong-hwa and Jang Seong-ho. Study on the History of Motion Picture Distribution in Korea (Hanguk Baegeupsa yeongu). Seoul: Korean Film Commission, 2003.

Korea Motion Picture Promotion Corporation (hereafter KMPPC). Korean Film Data

Collection (Hanguk Yeonghwa Jaryo Pyeollam). Seoul: KMPPC, 1977.

Lee, Byeong-Cheon. Developmental Dictatorship and The Park Chung-Hee Era: The

Shaping of Modernity in the Republic of Korea, edited by Lee Byeong-cheon, and translated

By Eungsoo Kim and Jaehyun Cho. Paramus, N.J.: Homa & Sekey Books, 2006.

Lee, Nae-young. “The Automobile Industry.” In The Park Chung Hee Era: The Transformation of South Korea, edited by Byung-Kook Kim and Ezra F. Vogel, 295-321. Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press, 2011.

Lee, Young-il, and Young-chol Choe. The History of Korean Cinema, edited by KMPPC. Seoul: Jimmondang Publishing Company, 1988.

Lee, Young-il. History of Korean Cinema (Hanguk Yeonghwa Jeonsa). 2nd ed. Seoul:

Sodo Publishing, 2004.

Lee, Young-jin. “50 Korean Film Industry Powers (Hanguk Yeonghwa Saneop Pawor 50).”

Cine21 (4 May 2006). Available here.

Accessed 20 November 2012.

McHugh, Kathleen, and Nancy Abelmann, eds. South Korean Golden Age Melodrama:

Gender, Genre, and National Cinema. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2005.

Moon, Chung-in and Byung-joon Jun. “Modernization Strategy: Ideas and Influences.” In The

Park Chung Hee Era: The Transformation of South Korea, edited by Byung-Kook Kim and

Ezra F. Vogel, 115-139. Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press, 2011.

Moon, Seok. “50 Korean Film Industry Powers No. 1-10 in 2007 (2007 Hanguk Yeonghwa

Saneop Pawor 50: 1wi-10wi).” Cine21 (3 May 2007). Available at:

http://www.cine21.com/news/view/mag_id/46067. Accessed 20 November 2012.

Park, Chung Hee. The Country, the Revolution and I. Translated by Leon Sinder. Seoul:

Hollym Corp., 1963.

Park, Ji-yeon. “From the establishment of the Motion Picture Law to its 4th revision (1961-

1984) (Yeonghwabeop Jejeong-eseo Je 4cha Gaejeong-ggajiui Yeonghwa Jeongchaek (1961-

1984 nyeon)).” In A History of Korean Film Policy (Hanguk Yeonghwa Jeongchaeksa),

Seoul: Nanam Publishing, 2005.

Rhyu, Sang-young and Seok-jin Lew. “Pohang Iron and Steel Company.” In The Park Chung

Hee Era: The Transformation of South Korea, edited by Byung-Kook Kim and Ezra F. Vogel,

322-344. Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press, 2011.

Rubin, Bernard. “International Film and Television Propaganda: Campaigns of Assistance.”

Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. Propaganda in

International Affairs 398, no. 1 (November 1971): 81-92.

Schatz, Thomas. “Hollywood: The Triumph of the Studio System.” In The Oxford History of

World Cinema, edited by Geoffrey Nowell-Smith, 220-234. New York: Oxford University

Press, 1996.

Schatz, Thomas. The Genius of the System: Hollywood Filmmaking in the Studio Era. New

York: Pantheon Books, 1988.

Shim, Ae-Gyung. “Anticommunist War Films of the 1960s and the Korean Cinema’s

Early Genre-Bending Traditions.” Acta Koreana 14, no. 1 (2011): 175-196.

Shim, Ae-Gyung and Brian Yecies, “Asian interchange: Korean–Hong Kong co-productions

of the 1960s”, Journal of Japanese & Korean Cinema 4:1 (2012): 15–28.

Standish, Isolde. “Korean Cinema and New Realism.” In Colonialism and Nationalism in

Asian Cinema, edited by Wimal Dissanayake, 65-89. Bloomington: Indiana University Press,

1994.

Wade, James. “The Cinema in Korea: A Robust Invalid.” Korea Journal 9, no. 3 (1969): 5-

12.

Yecies, Brian. “Systematization of Film Censorship in Colonial Korea: Profiteering From Hollywood’s First Golden Age, 1926-1936.” Journal of Korean Studies 10, no. 1 (2005): 59-84.

Yecies, Brian. “Parleying Culture Against Trade: Hollywood’s Affairs With Korea’s Screen Quotas.” Korea Observer 38, no. 1 (Spring 2007): 1-32.

Yecies, Brian, Ae-Gyung Shim and Ben Goldsmith, “Digital Intermediary: Korean Transnational Cinema.” Media International Australia #141 (November 2011): 137-145.

Yi, Chun-sik. “Formation of Ideology in the Park Chung Hee Era: Focusing on Historical Origins (Park Chung Hee Sidae Jibae Ideologi-Ui Hyeongseong: Yeoksajeok Giwon-upi

Jungsimeuro).” In Study on the Park Chung Hee Era, edited by Hanguk Jeongsin Munhwa

Yeonguwon, 173-208. Seoul: Baeksan Seodang, 2002.

Yi, Hyo-in, Jong-hwa Jung, and Ji-yeon Park. A History of Korean Cinema: from Liberation

through the 1960s. Seoul: Korean Film Archive, 2005.

Yi, Hyoin. Social and Cultural History of Korea Reflected in Films (Younghwaro Iknon

Hangook Sahoi Munhwa-Sa). Seoul: Gaemagowon, 2003.

Yoo, Sangjin, and Sang M. Lee. “Management Style and Practice of Korean Chaebols”.

California Management Review XXIX, no. 4 (Summer 1987): 95-110.

Notes

1 The authors thank Mark Morris and the journal’s referees for their valuable suggestions as well as Korean film maestro Darcy Paquet for his insights on producing in the new millennium. The Korea Foundation and Academy of Korean Studies have provided valuable assistance for this work in progress.

2 An increasing number of Korean producers, directors, actors, and post-production specialists are leaving their mark on films made in China. For example, Korean digital visual effects (VFX) firms operating in China contributed to Tsui Hark’s 2010 martial arts drama Detective Dee and the Mystery of the Phantom Flame; and his 3D film Flying Swords of Dragon Gate, produced in 2011. Korea’s Digital Idea shared the visual effects award for the latter film at the 31st Hong Kong Film Awards. Hur Jin-ho directed two films in China with Beijing-based producer Zonbo Media: A Good Rain Knows (2009) and Dangerous Liaisons (2012). CJ Powercast, Next Visual Studio and Lollol Media completed the VFX and 2D/3D digital intermediary for the Ningxia/Dinglongda/Huayi Brothers’ fantasy-action film directed by Wuershan – currently the highest grossing domestic film ever in China. Also, An Byung-ki, producer of Speed Scandal (2008) and Sunny (2011), both box office hits in China, directed the horror film Bunshinsaba (2012) in China. In Hollywood, Lee Byung Hun (G.I. Joe: The Rise of the Cobra (2009) and G.I. Joe: Retaliation (2013)) and Bae Doona (Cloud Atlas (2012)) have starred in blockbusters, while Park Chan-wook and Kim Jee-woon have directed Stoker (2013) and The Last Stand (2013) respectively. These are just a few examples of the collaborative inroads Koreans have been making in the film worlds in China and the US.

3 Sadly, this high-concept blockbuster film, starring Zhang Ziyi of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) fame, failed at the box office partly due to its release a few days before the 11 September attacks on the World Trade Centre in New York.

4 The results of this annual Cine21 survey can be found in Lee (4 May 2006) and Moon (3 May 2007). After leaving Sidus FNH in 2009, Tcha’s former company began concentrating on distribution and exhibition rather than production, for which Tcha had been well known.

5 Since the mid-to-late 2000s, various arms of the Korean film industry have been besotted with China. Shooting on location in China’s vast and inspiring landscapes, casting stars for wide or international audience appeal, and pursuing a range of official (joint and assisted) and unofficial collaborative co-productions are all factors that have helped the Korean film industry gain access to China’s massive and fast-growing market. Without question, the personal networks (guanxi) that Korean students at the Beijing Film Academy have developed in China since enrolling in this prestigious institution from the early 1990s – serving as local liaisons and consultants for both industries – have been invaluable to this process. Hence, Korean film companies and individual practitioners have thus far made stronger inroads into China than Hollywood, once believed to be the sole center of cinematic fame and success. For more on the types of contributions that Korean film people are currently making in China, see Yecies, Shim and Goldsmith (2011).

6 Patrick Frater, 10 May 2012. “CJ reassures over problem films.” Film Business Asia.

Available here. Accessed 14 November 2012.

7 Readers may be reminded here of the power shift in producing that is occurring in other parts of the world such as China, where internationally renowned Fifth Generation Chinese filmmaker Zhang Yimou unexpectedly split with his long-time producer of 15 years, Zhang Weiping, in October 2012, citing conflicts between the creative and business demands of filmmaking. Staff Reporter. 8 October 2012. “Zhang Yimou splits with long-term collaborator.” WantChinaTimes.com Available here. Accessed 14 November 2012.

8 See Lee and Choe (1988); Ho (2000); Byon (2001); Lee (2004); Park (2005); McHugh and

Abelmann (2005); and Yi, Jung, and Park (2005).

9 Here we specifically refer to the massive “landmark volume” edited by Kim and Vogel (2011), and its smaller companion edited by Kim and Sorensen (2011).

10 Other detailed accounts of Park Chung-hee’s legacy such as Kim (2004) and Lee (2006) also suffer from this oversight.

11 Rubin 1971: 81.

12 Park’s colonial experience is an important factor in this regard. Park was born in 1917, seven years after the Japanese colonized Korea. He was educated as a Japanese military officer in Manchukuo in 1940 under Japanese colonial authority which continued in Korea until 1945. As a military dictator, like the Japanese colonial authorities, he would have prioritized issues of national security and civil control above all else. It is no secret that Park deeply admired Japan’s Meiji imperial restoration responsible for Japan’s modernization, and also that he was profoundly influenced by Japanese colonial and military traditions. He once stated that ‘the case of the Meiji imperial restoration will be of great help to the performance of our own revolution. My interest in this direction remains strong and constant’ (1963: 121). For discussions of Park’s colonial experience and its long-term effects on his thinking, see Yi 2002; Yi 2003; and Moon and Jun 2011.

13 These guidelines were supplemented in two further ministerial decrees: the MPL Enforcement Ordinance (promulgated in March 1962) and the MPL Enforcement Rules (July 1962), consisting of fifteen and seven articles respectively. During the 1960s, the government released a series of film policy amendments through this hierarchical legislative framework.

14 For a discussion of the impact of censorship on directing and genre choice – that is, as a

determinant of which types of films were made and how stories were expressed within

particular narrative and aesthetic conventions – see Shim (2011).

15 Yeonghwa Japji (Film Magazine). December 1967: 226-229.

16 Yeonghwa Japji (Film Magazine). January 1970: 148.

17 This number was limited to six until 1988. In 1989, the number of prints allowed to circulate at any one time was increased to twelve, and between 1990 and 1993 this figure increased by one print per year. In 1994, this restriction was abolished, enabling films to be released on a nationwide basis, thus improving market conditions for both domestic and international films during this pre-multiplex rollout era. See Ahn (2005: 296-297).

18 Gukje Yeonghwasa (International Film Co.) 1969: 201.

19 For a detailed historical overview of Korea’s film distribution system, see Kim et al. (2003).

20 Members of the US film industry would have been made aware of this practice through articles published in Variety such as “No Union Spells E-c-o-no-m-i-c-a-l; All 11 Producers as Studio Owners” (8 May 1968).

21 In a few cases – for example, as a result of securing pre-sales funding from multiple exhibitors, each from a different province – a producer was required to contribute not more than 8% of the total budget (Kim et al. 2003: 12-24).

22 See Wade (1969: 10).

23 A similar phenomenon has occurred in the contemporary film industry in Korea. Between 2003 and 2005 Japanese distributors such as Shochiku, Comstock, and Gaga Communications rushed to purchased Korean films even before they were completed, accounting for between 70% and 80% of all Korean film exports and leaving Korean producers over-reliant on the Japanese market.

24 Standish 1994: 73.

25 Geundae Yeonghwa (Modern Film) December 1971: 23-31.

26 Other industries also ran into trouble around this time. Between 1969 and 1971, over 300

firms either went bankrupt or were on the verge of bankruptcy, desperately seeking state loans

to bail them out. See Cumings (1997: 362-363).

27 The KMPPA was established in 1957 to represent the interests of producers. By 1963, it

had become an interest group of registered producers, excluding independent producers from

its membership.

28 See, for instance, Kim (1994) and Park (2005).

29 Byon 2001: 233.

30 Gomery 2005: 3.

31 Schatz 1996: 225.

32 See Yoo and Lee (1987: 96). Samsung and LG, which were formed in the 1950s, and other family companies such as Hyundai, SK, and Daewoo, founded in the 1960s, are representative Korean chaebols. Over the past five decades, these Korean conglomerates have received enormous government subsidies and preferential treatment in all facets of domestic business.

33 See Kim (2004: 206). Park and his government pre-selected chaebols and nurtured them as industrial elites loosely based on a combination of personal connections and past business performance. In return, the chaebols designed and executed business plans that relentlessly backed the government’s drive to expand exports. This was one of the government’s chief strategies for generating foreign currency, a primary aim of development policy under the Park regime.

34 Moon and Jun 2011: 115.

35 It is likely that Shin saw the benefits of the studio model through his working relationship with Daiei and Toho Studios in Japan, which taught him some important lessons. For example, in 1961 Shin exported his film Seong Chunhyang (1961) through Daiei, and used Daiei’s advanced technology to complete the underwater scenes for Story of Shim Cheong (1962). Even after he was “kidnapped” and taken to North Korea in 1978, Shin invited Toho’s technical staff to North Korea and worked with them to complete his science-fiction quasi-Godzilla monster film Pulgasari (1985), a political allegory glorifying the unquenchable spirit of North Korean society.

36 Variety 17 April 1968.

37 Schatz 1988: 9.

38 Veteran producer Kim In-gi, who worked for 160 different film production companies between the 1950s and 1980s, reported positive experiences with making daemyeong films in the 1960s. This subcontracting practice enabled his unregistered production companies to remain in business, thus advancing his career.

39 This commission was in effect an advance tax payment on future box office revenues –

half was used to pay tax levied on box office gains and the other half went into the registered

producer’s purse. When box office returns were better than expected, an additional fee was

charged to the independent producer to pay for the increased tax bill.

40 Director Yun Bong-chun, president of the MPAK, wrote a column accusing registered producers of being greedy, taking advantage of independent producers twice over by selling production rights and then taking up import licenses (Silver Screen January 1965: 110).

41 Chosun Daily 3 February 1966: 5

42 Despite this, there was still room in the industry for passionate younger independent producers such as Ho Hyeon-chan and Choi Hyeon-min who specialized in art-house films, which were rarely attempted by registered producers.

43 This sudden increase in product overloaded the exhibition system: over 50 completed films produced in 1965 could not find outlets despite being scheduled for release in 1966. See KMPPC (1977: 46); and Yeonghwa Yesul (Film Art) January 1966: 132.

44 See Silver Screen March 1966: 70; Yeonghwa Segye (Film World) November 1966: 173; and Shin Dong-a October 1968: 359. In August 1966 revisions to the MPL banned daemyeong and declared that any registered producers involved in the practice would lose their registered status; following this directive, members of the KMPPA formally agreed to stop the practice of selling production rights to independent producers. However, some secretly continued to exchange their privileges to independent producers for high commissions, ranging between 40,000 and 50,000 won. Within two years, the commission to buy the rights to produce a single film had risen to an astounding one million to 1.5 million won. According to Lee (2004: 329), average production costs were 5-6 million won in 1961, a figure that rose to 10-12 million won in 1968/69.

45 One such case involved the death of an established director, Noh Pil, in late 1966. Noh tried to shake off his massive debts by making a profitable film but was unable to afford the production rights, and his attempt ended in suicide (Yeonghwa TV Yesul (Film TV Art) January 1967: 50; and Yeonghwa Japji (Film Magazine) January 1967: 102). Film magazines and newspapers made a martyr of Noh as a way of raising awareness of the human cost of the daemyeong system. The MPI’s new annual quota system was blamed for the worsening situation which had ultimately led to Noh’s death. (According to the Korean Movie Database (KMDB), Noh (1928-1966) debuted in 1949 with Pilot An Chang-Nam and directed a total of sixteen films. Most of Noh’s films were melodramas.)

46 In 1968 the MPAK accused the registered producers of charging excessive daemyeong commissions and monopolizing import licenses, and threatened a nationwide strike of its members. More than 600 film industry members joined demands for an amendment to the MPL and abolition of the production quota system. It was the first action of its kind to demonstrate the collective power of the MPAK. See Shin Dong-a October 1968: 359.

47 KMPPC 1977: 46.

48 Geundae Yeonghwa (Modern Cinema) December 1971: 23-31.

49 Although it was rarely policed, the Screen Quota System required that a minimum of one-third of all films screened per year should be of domestic origin. For a detailed overview of screen quotas in Korea, see Yecies (2007).

50 See KMPPC (1977: 243). This reward system originated in the 1958 Ministry of Education Notice No. 53, detailing preferential treatment to encourage domestic film production. According to this measure, specific import rights would be given to producers of high-quality domestic films, international award-winning films, exported films, and importers of cultural or news films and high-quality foreign films.

51 See (KMPPC 1977: 77). Popular films such as Marines Who Never Returned (1962), The Red Muffler (1964), and Love Me Once Again (1968) were exported through official channels to Taiwan, Hong Kong and Japan. Korea’s biggest export markets were Hong Kong and Taiwan, which accounted for 70-80% of total exports, while smaller numbers of films were exported to Japan and the US.

52 Importers operating independently of registered production companies were outlawed after the MPL was passed in 1963. From this date, import agencies mostly worked clandestinely and their activities were rarely documented. Film and Entertainment Yearbook (1969) published by Gukje Film Co. is one of the few sources that documents their activities.

53 KMPPC 1977: 77.

54 See Yeonghwa TV Yesul (Film TV Art) January 1967: 52 and Yeonghwa TV Yesul (Film TV Art) September 1967: 16. The case involving the export of a film for $100 was described by critic Lee Young-il as ‘shameful’ and ‘laughable’. In another case, a bundle of unclaimed (and unreleased) Korean film prints were found in a Taiwanese customs warehouse – they had been dispatched to Taiwan to create the appearance of an export contract.

55 Cho 2004: 20.

56 Director Lee Hyeong-pyo, who had direct experience of this kind of secret deal, said in an interview (with the authors, 26 October 2004) that registered producers simply provided their Hong Kong partners with a list of Korean names to include in the credits to make a given film look like a co-production.

57 Documents detailing these transactions can be found in the USC-Warner Bros. Archives. File: Japan # 16624B: Warner Brothers correspondence Re: South Korea 10 June 1963.

58 Film and Entertainment Yearbook 1969: 133.

59 The popularity of Hollywood films in Korea was first noticed in the 1920s and 1930s. On the basis of the huge influx of Hollywood films into the Korean peninsula during the Japanese occupation period, Yecies has dubbed the decade 1926-1936 ‘Hollywood’s First Golden Age’ in Korea (2005: 59).

60 Comments regarding audience experiences can be found in: Korean Cinema September 1972: 99-103.

61 KMPPC 1977: 160.

62 Discussed respectively in Lee (2011) and Rhyu and Lew (2011).

63 Jewell 2007.

64 Bergfelder, Harris, and Street 2007: 169.

65 Chung et al. 1997: 42-45.