Whose Peace? Anti-Military Litigation and the Right to Live in Peace in Postwar Japan

Tomoyuki SASAKI

This article examines two anti-military court cases that took place in Hokkaido during the 1960s and 1970s and their legacy today. It demonstrates how protesters against Japan’s Self-Defense Forces developed the notion of the right to live in peace through a creative interpretation of the Constitution.

Keywords

Self-Defense Forces, military, the Constitution, Article 9, peace, the right to live in peace, Hokkaido

Japan’s military, namely the Self-Defense Force (hereafter SDF), is a world military power. As of 2009, about 230,000 service members were working for the Ground, Maritime, and Air SDFs.1 In 2010, Japan had the sixth-largest military expenditure in the world.2 Since the early 1990s, the SDF has been dispatched overseas, for example, supporting US-led military actions in Iraq and Afghanistan, and frequently to participate in United Nations’ peacekeeping operations.

Yet, the Japanese Constitution does not recognize the nation’s right to possess any military organization or to engage in state belligerency. Article 9 reads:

Aspiring sincerely to an international peace based on justice and order, the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes.

In order to accomplish the aim of the preceding paragraph, land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained. The right of belligerency of the state will not be recognized.

This discrepancy between the constitutional ideal of unarmed peace and the presence of a military organization was a product of contradictory policies during the US occupation of Japan, from 1945 to 1952. During the initial stage of the occupation, SCAP (Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers) dismantled the Imperial Army and Navy, and helped the Japanese establish a peace constitution.3 As the Cold War escalated from the late 1940s, however, the major goal of the occupation shifted to security reinforcement. Just after the Korean War broke out, SCAP ordered Japan’s rearmament, and the National Police Reserve was created. Japan regained sovereignty in 1952, but continued to scale up its military within the framework of a subordinate military alliance with the Untied States. The National Police Reserve developed into the National Safety Forces in 1952, and then the SDF in 1954. The SDF became a fully-fledged military, with an army, navy, and air force.

Since the launch of rearmament, the legitimacy of the SDF under the constitutional order has been an object of incessant dispute. While conservatives have insisted on the constitutionality of the SDF, progressives, liberals and pacifists have contended that the Constitution barred the nation from creating such an organization. These contestations have been documented in detail, and Article 9 has offered powerful theoretical grounds upon which to critique both the existence of the SDF and the US-Japan Security Treaty or Anpo.4

This article aims to offer new insights into the discussion on the Constitution and the SDF by examining two anti-SDF court cases that took place in the towns of Eniwa and Naganuma in Hokkaido during the 1960s and 1970s. During the Cold War, the Japanese government concentrated SDF bases and personnel on this island due to its proximity to the Soviet Union.

In 1961, the Ground SDF’s four divisions in Hokkaido consisted of 32,000 service members, about one third of all Ground SDF service members deployed in Japan.5 On the one hand, this nurtured close economic relations between the SDF and those communities hosting SDF bases, such as Asahikawa and Chitose. The SDF engaged in disaster relief and civil engineering, and these activities were crucial in fostering local public support for the SDF.6 However, the concentration of SDF personnel and facilities also generated tensions with civilians. Frequent loud noise caused by firing during military maneuvers disturbed civilians’ everyday lives and jeopardized their health. During the Cold War, Hokkaido, together with Okinawa, became a focus for anti-base activism, and as Philip Seaton, Kageyama Asako, and Tanaka Nobumasa have noted in this journal, local struggles with the SDF and the US forces continue to this day in Yausubetsu in Eastern Hokkaido.7

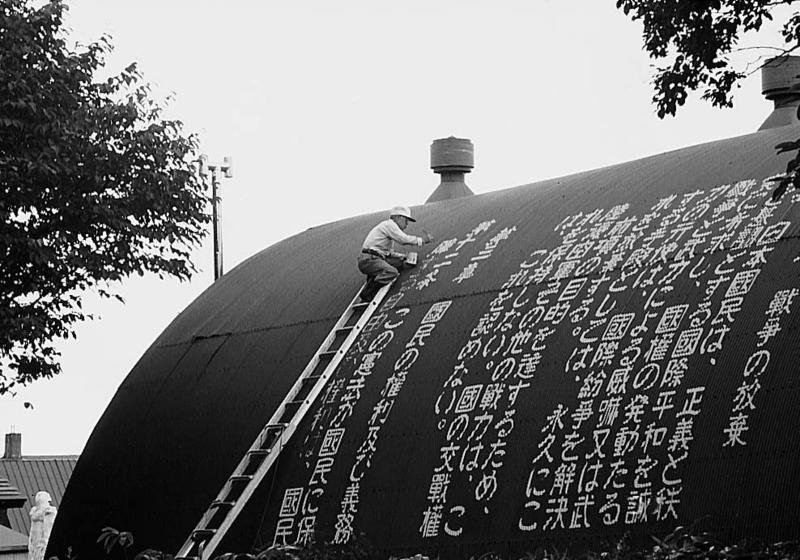

|

Kawase Hanji’s protest against the SDF on the roof of one of his buildings in the middle of the Yausubetsu Firing Range (Kawase passed away in 2009). |

This article demonstrates how protesters in Eniwa and Naganuma articulated the notion of the right to live in peace (heiwateki seizonken) in order to stress that national defense and the defense of individual and community welfare were not necessarily compatible. At the height of the social movements of the 1960s and 1970s, they identified the latter right through a creative interpretation of the Constitution, particularly the Preamble and Article 9, and maintained that peace must be understood not only as a principle predicated on the state’s diplomacy but also as a right that the people were entitled to enjoy. In the Naganuma case, a district court acknowledged the right to live in peace as a valid constitutional right and went on to recognize the unconstitutionality of the SDF. While great attention is paid to Article 9 with respect to the legitimacy of the SDF, this article focuses on the importance of including the right to live in peace in such a discussion.

Several works have mentioned the Eniwa and Naganuma cases. But these treat both cases mainly as judicial precedents.8 I am interested, however, not only in presenting the results of the cases, but in discussing Eniwa and Naganuma residents’ efforts to interpret the Constitution in their own terms and to illuminate the meaning of individual wellbeing—values that should not be subordinated to national defense—within the political and social context of 1960s and 1970s Japan.

The Eniwa Case

On December 24, 1962, the Northern Army, the regional army in charge of all four divisions in Hokkaido, filed with the Chitose Police Department a criminal complaint against Nozaki Takeyoshi and his brother Yoshiharu. Two weeks earlier, the brothers had cut telephone cables in the Shimamatsu maneuver field right next to their house and ranch in the town of Eniwa, an agricultural community near the prefectural capital, Sapporo. The brothers had long opposed SDF maneuvers near their house. By cutting the telephone cables, they had attempted to disconnect communications within the maneuver field. Based on the Northern Army’s complaint, the Sapporo District Prosecutor’s Office indicted the Nozaki brothers at the Sapporo District Court on March 7, 1963. The Nozakis were charged with having violated Article 121 of the Self-Defense Forces Act, which stated that “those who break or damage the weapons, ammunition, aircraft, and other defense equipment owned by the SDF shall be subject to imprisonment for five years or less, or a maximum fine of 50,000 yen.”9

|

Map showing Eniwa and Naganuma |

At first this incident did not receive much public attention. The Northern Army sought to treat the case simply as a criminal offense. A small number of individuals and organizations, however, understood the significance of the incident within the constitutional order and worked to awaken public consciousness. In April 1963, the Hokkaido Christian Association for Peace adopted a resolution supporting the Nozaki brothers “from the standpoint of defending the peace constitution.” Fukase Tadakazu, joined the brothers’ defense team. A member of the association, he was professor of law at Hokkaido University and would later play a central role in elaborating the notion of the right to live in peace. Various organizations, such as the Hokkaido Peace Committee and labor unions, rallied to support the brothers.10 These organizations would eventually form the Eniwa Incident Committee, which publicized the incident in newsletters, published records of the trial, and collected donations for the brothers’ defense.11

Encouraged by this support, the Nozaki brothers and their lawyers prepared to raise the constitutionality of the SDF as the central issue at the trial. At the first hearing, held in September 1963, the defense lawyers began by asking prosecutors whether the SDF constituted the sort of “war capability” (senryoku) that Article 9 of the Constitution banned.12 If the SDF was unconstitutional, then the SDF Act would also be legally invalid, and the prosecutors could not accuse anyone of having violated a law that had no legal validity. This was the defense strategy for establishing the Nozaki brothers’ innocence. A minor criminal case in a small town in Hokkaido thus became the first legal test of the SDF’s constitutionality.

The prosecutors responded to the defense team’s tactics by stating that the SDF constituted not war capability, but “defense capability” (boeiryoku), which Article 9 did not ban the nation from possessing.13 Successive conservative governments had been pursuing this distinction between war and defense capabilities since the early stages of rearmament, insisting that Japan had given up only belligerency, not the right to self-defense. As John Haley points out, the Cabinet Legislative Bureau acted as the single most vocal interpreter of the Constitution, and endorsed this view.14 In the famous Sunagawa Incident, seven citizens who opposed runway expansions at the US base in Tachikawa were indicted in 1957, but the Supreme Court agreed in 1959 that Japan, as a sovereign country, retained the right to self-defense.15 The prosecutors in the Eniwa case followed this interpretation.

The government’s and the prosecutors’ argument, based on the distinction between “defense capability” and “war capability,” was not at all novel within an international context. After the First World War, efforts were made to put an end to unbounded aggression by distinguishing between the types of war that states were entitled to wage and those they should abjure. The Kellogg-Briand Pact of 1928 renounced war “for the solution of international controversies” and war “as an instrument of national policy.” The spirit of the pact was further advanced after the Second World War. Article 2 (4) of the Charter of the United Nations required all members to settle international disputes by peaceful means and banned them from resorting to “the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence” of other states. These efforts did not outlaw war completely. The contracting parties of the Kellogg-Briand Pact understood that they had not given up the right to wage a war of self-defense. The Charter of the United Nations explicitly maintained that the Charter was not intended to “impair the inherent right of individual or collective self-defense.” Thus, states since the First World War have shared the conviction that a war’s legitimacy could be determined according to its purpose, and that only wars of aggression should be eliminated.16

The Nozaki brothers and their defense lawyers, however, did not accept the legitimacy of the concept of defense capability, even restricted to wars of self-defense. Their primary argument was that what the prosecutors identified as defense capability, which purportedly was to protect the lives of Japanese people, could in fact endanger the lives and well being of residents living in communities with military bases. They attempted to prove this by showing how the SDF’s incessant maneuvers had destroyed their dairy business, livelihood, and health.

The Shimamatsu maneuver field is located just north of Eniwa. The town’s close association with the military began in 1901, when the Seventh Division of the Imperial Army confiscated 8,822 acres for a training ground. Up until 1945, the scale of training remained small. The Seventh Division used the field mainly for rifle and machine gun practice, which occurred only several times a year. In September 1945, US occupation forces took over the field and began using it for military maneuvers. When the Korean War broke out, the field was used to train soldiers who were to be sent to the peninsula. Tanks and bombers took part in the exercises, resulting in serious environmental devastation. Trees were downed, and the soil lost its water-retaining capacity. After 1952, US forces continued using the field under the terms of the US-Japan Security Treaty.17

The Nozaki family’s struggle against the military maneuvers started in August, 1955, when US forces set up targets for ground-attack aircraft just 0.6 miles from the Nozaki family’s house and engaged in practice bombardments.18 The SDF joined the US forces in maneuvers late in 1956. Aircraft flew just 100 feet above the family’s house and farm during bombing runs, with 1,000 to 1,500 aircraft flying above the house a day. This inflicted serious damage on their dairy business and their health. Cows went mad due to the noise, some produced notably less milk, and some repeatedly delivered calves prematurely or miscarried. The father, the mother, and one of the brothers experienced serious hearing problems. The mother was especially badly affected. Her hearing problems and extreme fatigue led to her hospitalization in Sapporo in the spring of 1957, after which the family had its first face-to-face talk with the US Air Force mediated by the US Consul. After the family’s continual protests, the US Air Force agreed to suspend maneuvers near the house, and eventually withdrew its troops permanently in 1957. The SDF, however, continued maneuvers under the supervision of the US forces elsewhere, at the Misawa Base in Aomori Prefecture.

Exhausted by the noise and his continuing protest, the father was hospitalized in Sapporo in 1958. The two brothers and their sister continued to protest against maneuvers in various ways. They published a letter in the local newspaper Hokkai Times petitioning for the cancellation of maneuvers, to which the SDF did not reply; they collected signatures from neighbors; and they met with key SDF personnel from the Northern Eniwa Unit. However, the SDF took no steps to reduce the number of maneuvers or to cut down on noise. The brothers sometimes tried to prevent maneuvers by standing in front of the artillery, but service members removed them by force and resumed maneuvers each time. The family did receive some compensation in 1960, but this amounted to only 1.18 million yen, less than ten percent of the total financial damage to their business. Meanwhile, the parents remained in Sapporo to escape the noise and receive treatment (the mother would die during the trial). As the value of the cows and their milk continued to decrease, the family’s debts steadily increased.

The incident that led to the court case took place on December 11, 1962. That morning, the SDF conducted practice bombardments without notifying the family in advance as they had earlier promised to do. The two brothers went to the Northern Eniwa Unit to ask them to postpone the afternoon maneuvers until they could contact the headquarters of the Northern Army. Takeyoshi, the elder brother, told the supervisors at the unit that if the SDF did not postpone the maneuvers, he and his brother would resort to force. At one o’clock in the afternoon, the SDF resumed maneuvers. Takeyoshi called the Northern Army to ask them to desist. The other brother, Yoshiharu, and his sister, Kazuko, went to the field to protest directly, but were ignored. Yoshiharu then cut the telephone cables in front of service members. In response, several angry service members hit and choked him. The SDF resumed their exercises the next day. That day, on their way to the maneuver field, Takeyoshi and Yoshiharu cut more telephone cables.

After recounting these events in court, Nozaki Takeyoshi asked the court what else he could have done to protect his family’s livelihood. Then he cited one passage from the preamble to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights: “it is essential, if man is not to be compelled to have recourse, as a last resort, to rebellion against tyranny and oppression, that human rights should be protected by the rule of law.”19 By citing this, Takeyoshi pleaded the brothers’ innocence, the injustice the SDF had committed against them, and the incongruity of the accusation against them. According to him, he and his family were the victims, not the victimizers.

The prosecutors responded by presenting the Nozaki brothers’ act of cutting telephone cables as illegal and irrational. In their view, the Nozaki family had been benefiting from the SDF on a daily basis. The SDF allowed the family to use a reservoir inside the maneuver field to generate electricity and for drinking water. The SDF also provided the family with land, rent-free, to build a pipe connecting the water reservoir to their house. When the pipe was clogged with mud in September 1962, the Northern Eniwa Unit unclogged it at no charge at the family’s request. The prosecutors also downplayed the noise problem. Responding to protests by the family, an officer from the Northern Army visited the family in 1962 to check the noise levels for himself. On that day, according to the prosecutors, the SDF was conducting firing drills with tanks, but the noise was so minimal that Nozaki Takeyoshi grumbled the officer had deliberately chosen a quiet day. The prosecutors used this one-off incident to argue that the Nozaki brothers were exaggerating their suffering.20 For them, the Nozaki brothers were simply insolent residents who did not sufficiently appreciate the benefits they were receiving from the SDF. The prosecutors strongly argued that the SDF was working for the improvement of people’s lives. They chose to ignore the argument that what they identified as “defense capability” could actually destroy individual lives in the name of the defense of the nation-state.

|

Joint US-SDF military training conducted in Hokkaido (Yausubetsu, 2008) |

The Right to Live in Peace

When arguing for the incompatibility between the defense of the nation and that of individual lives, the Nozaki brothers and their defense team struggled to locate the centrality of individual rights within the postwar constitutional order. For this purpose, as the trial proceeded, they gradually adopted the notion of the right to live in peace.

Legal scholars have long agreed that the Constitution recognized the “right to life” (seizonken). Article 25 stipulated that all people had “the right to maintain the minimum standards of wholesome and cultured living,” and that the state was responsible for “the promotion and extension of social welfare and security, and public health.” Among the American officials in SCAP who drafted the Constitution were a number of New Dealers, who held that the people’s rights extend to the social realm. Article 25 prepared the legal basis on which the state enacted the Daily Life Security Law of 1950, guaranteeing the people the right to petition for public assistance if they had difficulty in maintaining a minimum standard of living. As Deborah Milly has demonstrated, people actively resorted to this article when criticizing the gap between the ideal of the welfare state and the state’s actual reluctance to support economically disadvantaged people.21

In the early 1960s, some scholars began to claim that the postwar constitution guaranteed not only the people’s right to live but also their right to live in peace. Behind this claim was the sense of crisis (shared by these scholars as well as many other Japanese) about democracy in the mounting Cold War and growing awareness of individual rights and freedoms. The defining event was the railroading through the Diet in 1960 of the renewed and revised US-Japan Security Treaty, which led to popular protest on an unprecedented scale. Although implementation of the treaty could not be prevented, those who cultivated civic consciousness by engaging in and/or witnessing this protest launched diverse citizens’ movements throughout the following decade. The anti-Vietnam war movement flourished.22 Feminist activists denounced recurring sexism in politics and society (including social movements).23 Pollution victims in Minamata, backed up by supporters all over Japan, raised awareness of environmental health risks at local, regional, and national levels.24 In these movements, the subject of protest increasingly shifted to individual citizens. In his study on activism in this era, Wesley Sasaki-Uemura has demonstrated that participants were not simply manipulated by party politics, but had concerns and agendas that stemmed from their everyday lives, and made conscious decisions to pursue activism.25 Similarly, Simon Avenell, who has traced the evolution of the concept of citizen or shimin in postwar Japan, shows that movements in this era envisioned a civil society autonomous from the state and the established left.26

This trend was by no means unique to Japan. The 1960s was also an era of protest worldwide, reaching its peak in 1968 with such events as the May protest in France. Immanuel Wallerstein has suggested viewing the movements that took place worldwide throughout the 1960s as a single movement, calling it “the revolution of 1968,” a revolution in and of the world-system. By this time, the United States and its allies had recovered from the damage of World War II and gained significant economic stability. The old left, which had been fighting for the improvement in the quality of people’s lives, quickly became a part, not an antithesis, of the existing system. People began identifying persistent social inequalities. They demanded manifold rights that were not necessarily represented within traditional party politics, and no longer tolerated these rights being treated as secondary to the interests of a larger entity, such as the working class or the nation. In sum, Wallerstein sees the protests in the 1960s as an anti-systematic critique at the global level.27

In this political and social atmosphere, the welfare of those living in communities with bases attracted a great deal of attention in Japan. Legal scholars went beyond the conventional understanding of peace as a diplomatic issue, and presented it as a fundamental human right. Hoshino Yasusaburo, who specialized in constitutional law, was the first to advocate the notion of the right to live in peace. He focused on the second paragraph of the Preamble to the Constitution. This paragraph declared the Japanese people’s commitment to international peace and the renunciation of tyranny, slavery, oppression, and intolerance. The paragraph ends: “We recognize that all peoples of the world have the right to live in peace, free from fear and want.” While the body of the Constitution included no article articulating the right to live in peace in concrete terms, Hoshino suggested understanding Article 9 and the right to live in peace as mutually reinforcing. While Article 9 appeared to have little to do with the people’s rights, Hoshino argued that the diplomatic policy determined by Article 9 (that is, unarmed peace) actually ensured the people a peaceful living environment. This article had liberated the Japanese from the anxiety of war, military service, and other obligations to participate in national defense, and made sure that their freedom of thought, conscience, speech, and expression could not be restricted for military purposes. This article, the law scholar continued, enabled the people to “employ all available manpower and wealth to build a free and peaceful society.” In his interpretation, the right to live in peace stipulated in the Preamble meant protecting this type of living environment. By construing the right to live in peace in this way, Hoshino insisted that the pacifism outlined in the Constitution must be the principle for determining not only the state’s diplomacy but also the extent of individual rights.28

At the beginning of the Eniwa trial, the right to live in peace was not well recognized by the public, or even among legal scholars. While the Nozaki brothers and their defense lawyers sometimes used the expression “the right to livelihood” (seikatsuken), they did not explicitly state that the SDF had violated the Nozaki family’s right to live in peace. Toward the end of the trial, however, they gradually recognized that a combined interpretation of the Preamble and Article 9 could help them effectively to denounce the SDF’s maneuvers. This theoretical breakthrough was made possible by the growing size of the defense team that, by the end of the trial, had mushroomed to more than four hundred members. They felt urged to defend the Constitution from arbitrary interpretations, and actively exchanged ideas and inspiration.29

In his final defense plea in January 1967, Fukase Tadakazu, a leading member of the defense team, explained the concept of the right to live in peace. While stressing the meaning of the Preamble and Article 9, Fukase also articulated a new interpretation of this concept, rooted in Article 13. This article, strongly influenced by the US Declaration of Independence, stipulates that the people’s “right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” was the “supreme consideration in legislation and in other governmental affairs.” Whereas this article added that the quest for this right should not interfere with “public welfare,” Fukase maintained that Article 9 did not allow military affairs to be interpreted as “public welfare.” Instead, he argued, the people were entitled to pursue happiness fully without worrying about being mobilized, having their freedom of speech restricted, or having their properties and lands confiscated for the state’s war effort. At the end of this plea, Fukase retrospectively defined the Nozaki brothers’ struggle against the SDF as a fight for the right to live in peace, and claimed that, for the brothers, aspiring to lives free from military maneuvers was exercising their constitutional right.30

The Sapporo District Court handed down its verdict on March 29, 1967. While finding the Nozaki brothers not guilty, Judge Tsuji refrained from making a judgment on the SDF’s constitutionality in relation to Article 9 and the right to live in peace. Relying on the Self-Defense Forces Act, the prosecutors had accused the Nozaki brothers of damaging “SDF-owned equipment used for the purpose of defense.” Judge Tsuji, however, stated that the telephone cables cut by the brothers could not be considered “SDF-owned equipment.” Typical examples of SDF-owned equipment included weapons, munitions, and airplanes. Therefore, the SDF Act could not provide legal grounds on which to try the Nozaki brothers. The judge concluded that since the brothers had not violated the SDF Act and therefore were not guilty, he had no reason to address the constitutionality of the SDF.31

This verdict offered no solution to the Nozaki brothers’ fundamental predicament. The central issue of the trial had been the constitutionality of the SDF, and the defense team had designed their arguments accordingly. But the court disregarded this. The implication was that the SDF could continue carrying out its maneuvers (and it did), and the brothers’ right to live in peace would continue to be threatened. After the trial, the brothers expressed their sense of betrayal, saying that they now wanted to sue the court.32 Fukase Tadakazu, on the one hand, admitted that the court had defended certain of the brothers’ rights by rejecting the prosecutors’ insistence that they be punished. On the other hand, he also pointed to the unresolved contradiction between the presence of the SDF and the constitutional principle of unarmed peace, and presented it as a problem whose persistence could be explained partly by the fact that the Japanese people in general had allowed the contradiction to grow so acute.33

The Naganuma Case

The hope, kindled by the Nozaki brothers, to establish a constitutional right to live in peace did not expire with the conclusion of the case. Their efforts significantly influenced the plaintiffs’ arguments in the next anti-SDF litigation.

That case took place in Naganuma—a small farming town near Sapporo, not far from Eniwa—in 1968, about a year after the verdict in the earlier case. On May 30 of that year, the Minister of Agriculture and Forestry and the Hokkaido Prefectural Government notified the mayor of Naganuma that the Defense Agency planned to build a new Nike J missile base in the town. Its original form, Nike Hercules, had been developed in the United States in the 1950s, and the United States had provided Japan with a license to manufacture this surface-to-air missile domestically. As the United States, plagued by the Vietnam War, cut financial support for Japan’s defense during the 1960s, the Japanese government took ever greater responsibility for its own defense, and Japanese firms strove to manufacture weapons with US technological support. The Nike J missile was a product of such effort.34 In 1967, the Japanese government launched the Third Defense Buildup Plan, which included strengthening of air defense through domestically manufactured Nike missiles as a primary goal.35

|

Nike Hercules (Photo courtesy of the White Sands Missile Range Museum) |

When announcing the construction of the Nike missile base in Naganuma, the Minister of Agriculture and Forestry and the Hokkaido prefectural government called on the mayor to agree to trees being cut down on Mount Maoi to provide space for the missile base. The Japanese government had designated this mountain as a national forest preserve in 1897. Residents of Naganuma had been relying on it for the protection of the watershed since then.36 Upon notification from the Minister and the Hokkaido prefectural government, the mayor declared his support for the project. On June 10, he summoned the town assembly. Of the 26 assembly members, 17 endorsed the project on the condition that the central government would compensate the town for any damages that the building of the base might cause and that it would not turn the base into a nuclear base. On June 13, the mayor visited the Defense Agency in Tokyo to convey the assembly’s agreement and to ask them to adhere to these conditions. On July 17, the assembly formally approved the Nike missile base plan with the support of 22 members.37

The Forestry Agency, an extra-ministerial bureau of the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, held two public hearings to explain to residents the procedure for building the Nike missile base in September 1968 and May 1969. While failing to reach any consensus with town residents, on July 7, 1969, the Ministry removed an 86.7-acre area of Mount Maoi from the forest preserves list, thereby permitting the Defense Agency to cut down trees and build the base there. On the same day, 173 residents who opposed the base filed a lawsuit in the Sapporo District Court against the Minister of Agriculture and Forestry, petitioning for cancellation of the delisting. They feared that deforestation would impair the role played by Mount Maoi in deterring natural disasters.38 Anticipating that it would take a long time for this case to be settled in court, they also asked the court for an injunction against the government’s tree-felling until the case was settled.39

The Sapporo District Court responded promptly. It issued an injunction on August 22 to prevent tree felling. Judge Fukushima argued that tree felling might cause irreparable damage to the community, and that the SDF’s constitutionality needed to be discussed in relation to the spirit of the Constitution prior to the construction of the base.40 The state, in the name of the Minister of Agriculture and Forestry, appealed to the Sapporo High Court the following week. On January 23, 1970, the high court reversed the district court’s decision, and permitted tree felling and construction to continue. The high court stated that the government’s plan for alternative facilities such as dams was satisfactory for watershed protection.41 The plaintiffs decided not to appeal. Considering the fact that the Supreme Court tended to rule in favor of the state, it was unlikely that the high court’s decision would be overturned. Following this decision, in June of the same year, the clearing of trees began. Despite this setback, the plaintiffs chose to continue challenging the legality of the delisting of Mount Maoi from the forest preserves list, demanding that the court repeal the delisting retroactively.

One major issue contested in court was whether the delisting of Mount Maoi for the construction of the Nike base assumed any public interest. Under the Forestry Law, such delisting was allowed only when the Minister of Agriculture and Forestry deemed that it was required for “reasons pursuant to the public good” (koekijo no riyu) (Article 26). From the outset of the trial, the state insisted that the military bases provide a public good, arguing that without them, the state would be susceptible to foreign attack. The state did recognize that Mount Maoi as a forest preserve constituted a public good for local residents by providing water resources for drinking and irrigation purposes, and as a protection against floods. But the state also maintained that such a good was less important than the public good that the Nike base would pursue, and that therefore the lesser public good could be sacrificed.42 In this argument, we see the same logic that the prosecutors resorted to in the Eniwa case—the logic that individuals should surrender their particular interests and desires for the sake of the common welfare of a greater number of people, or the nation.

The plaintiffs, however, held that the delisting of Mount Maoi from the forest preserves list lacked a compelling reason pursuant to the public good, and therefore lacked legal validity. Their key argument was that the delisting and the subsequent construction of the Nike base would violate their constitutional right to live in peace, and that any act that betrayed the principles of the Constitution could not be pursued in the name of the public good.43

The state insisted upon the constitutionality of the SDF by arguing that the SDF possessed only a minimum level of defense capability. Frustrated at the lack of specificity and concreteness in the state’s explanation, the plaintiffs requested permission to call on people with distinctive knowledge of the SDF, including top SDF officers, to give testimony so that the court could objectively judge whether the SDF possessed only minimal defense capability.44 While the state declined the request to summon SDF officers, the judge agreed with the plaintiffs. Between the sixth and twenty-fifth hearings, a total of eighteen people testified in court, including the three Chiefs of Staff of the Ground, Maritime, and Air SDF, a former Chief of Staff of the Air SDF, and a few other officers.

One of the points the plaintiffs wished to clarify was how the Nike missiles deployed in Naganuma, as well as other weapons, could be justified as defense capability. The SDF officers explained that the equipment the SDF possessed was meant to eliminate the possibility of foreign attacks. The SDF would resort to its use only if Japan was attacked by external forces, and had no intention to use it to invade other countries. Nor did it possess equipment sufficiently advanced to send troops overseas. The officers frequently used the term “exclusive defense” (senshu boei) to refer to this non-aggressive security policy, rationalizing the introduction of the Nike missiles within this framework. The one and only function of the Nike missiles was to destroy any enemy planes that invaded Japanese airspace. Under no circumstances could they be used to attack and destroy targets outside Japan.45

In addition to these top SDF officers, the court also summoned civilian experts specializing in the SDF, politics, and law. These experts expressed strong skepticism at the SDF officers’ argument. One of the fears that they shared was the risk of accidents caused by missile explosions. Osanai Hiroshi, a military commentator, and Hayashi Shigeo, a board member of the Japan Peace Committee, both made this point. At a base in Middletown, New Jersey, in 1958, eight Nike missiles had exploded accidentally, killing ten people while they were installing arming mechanisms. In Okinawa, which was still under US administration and armed with Nike missiles, falling boosters had inflicted damage on civilians and their residences during military maneuvers. Although the state asserted the safety of the Nike base, no one could guarantee that such accidents would not happen in Naganuma.46

These experts also cautioned that the government might turn the Nike missile base into a nuclear base. The American Nike-Hercules, from which the Japanese Nike was developed, had optional nuclear warheads, and indeed, many missiles deployed in the United States were equipped with nuclear warheads. The Defense Agency had stressed that Nike J missiles would be produced with non-nuclear warheads and insisted that changing the warheads was structurally impossible. But Osanai presented a different view. While agreeing on the difficulty of changing warheads on existing Nike missiles, he also indicated that the launchers for the missiles were imported from the United States, and that these launchers could launch both nuclear and non-nuclear missiles. This meant that if the Japanese government were to decide to produce nuclear missiles, the launchers could easily be used for these as well. While this trial was going on, it was unclear whether Nike missiles in Okinawa bore nuclear warheads. This uncertainty surely fueled Osanai’s fear.47

The experts were alarmed not only by the Nike base per se, but also by a much larger problem, namely the relentless growth of the SDF under US tutelage. While the trial was underway, the Vietnam War was at a stalemate. Against this backdrop, the United States and Japan were forging increasingly intimate ties as allies in the Pacific. In November 1969, US President Nixon and Japanese Prime Minister Sato issued a joint statement reasserting the importance of the US-Japan Security Treaty in maintaining the “peace and security of the Far East.”48 Yamada Akira, a military commentator, pointed out in 1971 that Japan’s military expenditure had been growing by ten percent per annum, and that Japan ranked seventh in the world in military expenditure. He rejected the view that this would enhance the security of Hokkaido or Japan. Quite the contrary, he repeatedly argued that the primary mission of the SDF was to protect US bases in Japan, referring to the fact that the Nike base was being constructed near Camp Chitose, a communications base owned by the US Air Force. Takahashi Hajime, a military commentator and former lieutenant colonel in the Imperial Navy, made a similar point when he reminded the court that a large number of US troops were also stationed in the Misawa Base in Aomori Prefecture. Both Yamada and Takahashi maintained that an advanced military facility such as the Nike base would have the effect of attracting, rather than repelling, an attack from an enemy.49 They were anxious that, if war broke out, Naganuma residents in particular and Japanese people more broadly might have to sacrifice their lives for the sake of what the US and Japanese governments called the “peace and security of the Far East,” which was in fact best understood as US hegemony and dominance in Cold War Asia.

The testimonies of the civilian experts were in sharp contrast to those of the SDF officers. Whereas the latter simply reiterated that the Nike base would enhance the security of Hokkaido and Japan, the civilian experts countered with concrete and detailed data and examples. They reminded the court of the centrality of the welfare of local residents who would have to endure any catastrophe caused by missile accidents or a war. At a fundamental level, these civilian experts agreed that the SDF infringed upon the people’s right to live in peace and that the state could not pursue the deforestation of Mount Maoi for the construction of the Nike base in the name of the public good.

The Sapporo District Court handed down its verdict on September 7, 1973, about four years after the plaintiffs filed their lawsuit. Judge Fukushima, who had issued the injunction against the government’s deforestation of Mount Maoi, recognized the right to live in peace as a constitutional right. For him, the three principles of the Constitution—popular sovereignty, respect for fundamental human rights, and pacifism—had to be interpreted in an integrated manner. From this standpoint, he fully accepted the plaintiffs’ argument concerning the relationship between the Preamble and Article 9 of the Constitution, namely the argument that the individual’s right to live in peace and the state’s security policy must complement each other.50

The recognition of the right to live in peace influenced the judge’s interpretation of the notion of “defense.” While the state had stressed that Article 9 did not renounce wars of self-defense nor ban the possession of defense capability, Fukushima deemed it unlikely that the Constitution that guaranteed the right to live in peace would at the same time justify war depending on its purpose. Wars of self-defense fought using defense capabilities, no less than wars of aggression fought using war capabilities, would require the mobilization of human and material resources, and risk violating the people’s right to live in peace. The judge defined “war capability” as “an organization constituted by human and material means that could be employed for the purpose of war,” and within this definition it was impossible to demarcate a line between war capability and defense capability.51 The judge therefore regarded the SDF as an organization that possessed war capability, and was, hence, unconstitutional. Since construction of the Nike base could not be pursued in the name of the public good under the constitutional order, he ordered the removal of the base and the restoration of the forest preserve.52 This was a historic verdict in that it was the first court decision to rule the SDF to be unconstitutional.

The Naganuma residents’ fight, however, did not end at the district court. The state immediately appealed to the Sapporo High Court, which, in 1976, reversed the district court’s decision. For our purpose, three points must be mentioned concerning this verdict. First, the high court refused to admit the possibility that the plaintiffs might suffer disadvantages from the deforestation of Mount Maoi. The court held that because alternative facilities would work to prevent such natural disasters as floods and mudslides, the Nike base would not endanger the plaintiffs’ lives.

Second, the court refused to acknowledge the judicial validity of the plaintiffs’ insistence on the right to live in peace. While admitting that the Preamble expressed “noble ideals” (suko na rinen), the court held that the Preamble, unlike the articles, did not provide any concrete and specific judicial standard upon which one might base a lawsuit. In other words, rights mentioned in the Preamble were so abstract that the violation of these rights alone could not establish a sufficient basis to sue. Similarly, the court insisted that the agendas set up by Article 9, whose contents were more concrete than those in the Preamble, were only meant to protect the interests of “the people in general” (ippan kokumin), not the particular interests of “particular people” (tokutei no kokumin). Despite the plaintiffs’ tireless efforts, the court failed to recognize manifold experiences within the category of “the people,” and could perceive “the people” only as a unitary, static entity detached from the material context.

Third, the Sapporo High Court chose to avoid discussion of the SDF’s constitutionality. It maintained that there were certain legislative and executive issues whose constitutionality should not be measured by the judiciary. These were issues directly related to fundamental national governance that might have an enormous impact on the “maintenance of the existence of the state” (kuni no sonritsu iji).53 This was consistent with a tendency not to challenge fundamental governmental acts, which is a prominent feature of the Japanese judicial system.54 One reason is the conviction among a fair number of judges and legal scholars that there were certain non-justiciable, highly political questions. They believe that the elected legislature and cabinet should deal with these issues, and that the judiciary, which is not elected by the people, should avoid doing so. Another reason is that for many decades, a single party—the LDP—maintained power, and there were cozy relations between the government and the courts. For these reasons, the courts were reluctant to object to government activities, especially those related to defense issues, based on the assumption that the judiciary should not undermine coherence in governmental policies by ruling on the constitutionality of individual issues. The higher the level of the court, the more salient this tendency became.55 In this sense, the Sapporo High Court’s verdict was not particularly surprising.

The plaintiffs appealed to the Supreme Court, which dismissed the appeal in 1982. The verdict was simple. Given that the state had already finished building the Nike base and the alternative facilities intended to ameliorate the effects of the tree felling, including mudslide dams, the court held that the plaintiffs had lost the grounds to demand legal protection. In the court’s view, the alternative facilities had resolved the danger of natural disasters previously cited by the plaintiffs. The court did not mention the constitutionality of the SDF nor the people’s right to live in peace, thereby implicitly confirming the idea that these were non-justiciable questions.56 With this loss at the Supreme Court, the plaintiffs had no further legal means of stopping the operation of the base.

Conclusion: The Significance and Legacies of the Eniwa and Naganuma cases

Although the Eniwa and Naganuma cases did not end in a satisfactory manner for the protesters against the SDF, they demonstrated that the meaning of the Constitution was not fixed but open to creative (re)interpretation. While the right to live in peace was written into the Constitution, it was articulated through the Eniwa and Naganuma cases. Here we need to distinguish between the language of democracy and its practice. While language is certainly important since it gives intelligibility to the concept of democracy, it is equally important to employ and contest it in actual contexts to expand its practice. Writing in the aftermath of the Anpo protest, the critic and philosopher Tsurumi Shunsuke insisted on the true “making” (tsukuru) of the Constitution.57 Similarly, Watanabe Yozo, writing before he became a member of the defense team for the Nozaki brothers, called for a transition from “life as given” (ataerareta seikatsu) to “life in the making” (tsukuru seikatsu).58 These expressions suggest that in order to establish a society within which the Constitution would truly defend popular welfare, the people, as sovereign, must not simply content themselves with having a democratic constitution, but must actively involve themselves in the critical examination of state policies with recourse to the Constitution. There is no doubt that the protesters in the Eniwa and Naganuma cases put this spirit into practice. They sought to extend the application of peace not only to diplomacy but also to people’s quotidian life. By doing so, they illuminated the extreme difficulty of ensuring the military defense of the entire nation without forcing some—often those in communities close to bases—to sacrifice their welfare.

While the Nozaki brothers and the Naganuma residents failed to convince the courts that the right to live in peace should be prioritized over national defense, their activism left important legacies. Legal scholars have continued to articulate the notion of the right to live in peace, thereby contributing to its dissemination as a widely accepted right in the intellectual community.59 Furthermore, the right to live in peace has recently received new legal attention in the context of Japan’s participation in the Iraq War. When the war began, the Diet, then dominated by the LDP, passed a law in 2003 that would enable the dispatch of the SDF for humanitarian causes. Overseas dispatch of the SDF had been conducted since the early 1990s under the auspices of United Nations’ peacekeeping operations, but the SDF’s dispatch to Iraq became controversial since service members were to be sent to an active war zone and the assignment was not part of a United Nations operation. Although the law limited the areas of service members’ activities to non-combat zones, it was evident that the border between combatant and non-combatant zones could easily become blurred.

Citizens who opposed this overseas dispatch as unconstitutional filed twelve lawsuits in eleven cities all over Japan. In these cases, the plaintiffs resorted to the right to live in peace to argue for the suspension of the SDF’s mission to Iraq. They argued that by mobilizing the SDF to collaborate with the US war effort in Iraq, the state infringed upon the people’s right to live in a country free from war. Although none of the courts acknowledged that Japan’s participation in the Iraq War resulted in a violation of the plaintiffs’ right to live in peace in any concrete manner, the Nagoya High Court delivered a landmark verdict on April 17, 2008. While supporting the original verdict of the district court, which had dismissed the plaintiffs’ petition for an injunction, the high court made two important points. First, the court pointed out that some of the SDF’s activities in Iraq had violated Article 9, which prohibited the “threat and use of force as means of settling international disputes,” because SDF service members’ activities were an integral part of the activities of armed soldiers from other countries. Second, the court maintained that the right to live in peace did not merely denote an abstract ideal of the Constitution, but actually was a right with concrete content, directly tied to other rights enumerated in the Constitution. This means that the people could request a court to take legal measures if that right was violated, that is, if a war risked people’s freedoms and lives, or if people were forced to participate in the state’s war effort.60 For strategic reasons, the plaintiffs did not appeal. While they had lost their case, they were excited at the high court’s affirmation of the right to live in peace. They were afraid that if they appealed the Supreme Court would reverse the high court’s decision. They preferred, therefore, to let the high court’s decision stand as a legal precedent.

In this way, contestation over the right to live in peace continues. Since the Supreme Court has not yet ruled on its legal validity, there is no consensus about the extent to which the people are entitled to enjoy this right. Now that the SDF’s withdrawal from Iraq is complete, no litigation against the SDF’s overseas dispatch is being pursued. If the Japanese government decides to send the SDF abroad in the future, it is likely that lawsuits will be filed again petitioning for the protection of the people’s right to live in peace from Japan’s participation in a war abroad. The Eniwa and Naganuma cases illustrate clearly the incompatibility between individual welfare and the military defense of the nation state. Ever since these cases, claiming universal, collective peace for all the people of the nation has become extremely difficult. Whenever peace is discussed, it is imperative to consider how to define that peace, and whom that peace is for.

Tomoyuki SASAKI is a historian of modern Japan. He is an assistant professor at Eastern Michigan University. [email protected].

Recommended citation: Tomoyuki SASAKI, “Whose Peace? Anti-Military Litigation and the Right to Live in Peace in Postwar Japan,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol 10, Issue 29, No. 1, July 16, 2012.

Articles on related subjects

•Tomomi YAMAGUCHI and Muto Ruiko, Muto Ruiko and the Movement of Fukushima Residents to Pursue Criminal Charges against Tepco Executives and Government Officials

•David T. Johnson, Covering Capital Punishment: Murder Trials and the Media in Japan

•Richard Falk, War, War Crimes, Power and Justice: Toward a Jurisprudence of Conscience

•Tomomi YAMAGUCHI, The Kaminoseki Nuclear Power Plant: Community Conflicts and the Future of Japan’s Rural Periphery

•David McNeill, Implausible Denial: Japanese Court Rules on Secret US-Japan Pact Over the Return of Okinawa

•Andrew Yeo, Back to the Future: Korean Anti-Base Resistance from Jeju Island to Pyeongtaek

•David McNeill, Secrets and Lies: Ampo, Japan’s Role in the Iraq War and the Constitution

•C. Douglas Lummis, The Smallest Army Imaginable: Gandhi’s Constitutional Proposal for India and Japan’s Peace Constitution

•Klaus Schlichtmann, Article Nine in Context – Limitations of National Sovereignty and the Abolition of War in Constitutional Law

•David McNeill, Martyrs for Peace: Japanese antiwar activists jailed for trespassing in an SDF compound vow to fight on

•Tanaka Nobumasa, Defending the Peace Constitution in the Midst of the SDF Training Area

Notes

2 The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

3 On the making of the new constitution, see Shoichi Koseki, The Birth of Japan’s Postwar Constitution (Boulder: Westview Press, 1997); Ray Moore and Donald Robinson, Partners for Democracy: Crafting the New Japanese State under MacArthur (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002); John Dower, Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of WWII (New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 1999), Ch. 12 and 13.

4 Glenn Hook, Militarisation and Demilitarisation in Contemporary Japan (London: Routledge, 1995); Glenn Hook and Gavan McCormack, Japan’s Contested Constitution; Documents and Analysis (London: Routledge, 2001); Kenneth Port, Transcending Law: The Unintended Life of Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution (Durham: Carolina Academic Press, 2010).

5 Arai Shigenori, ed., Jieitai nenkan 1962 (Tokyo: Bōei Sangyō Kyōkai, 1962), 314-318. On the militarization of Hokkaido in general, see Matsui Satoru, “Gunji kichi Hokkaido” in Hokkaido de heiwa o kangaeru, ed. Fukase Tadakazu (Sapporo: Hokkaido Daigaku Tosho Kankōkai, 1988).

6 See Asahikawashi Henshū Iinkai, Asahikawashi-shi 2 (Asahikawa Shiyakusho, 1957), -863-869; Chitoseshi-shi Hensan Iinkai, ed., Chitoseshi-shi (Chitoseshi, 1983), 1249-1250. Other communities that developed close ties with the SDF include Bihoro, Nayoro, and Kami-Furano, to name a few.

7 Philip Seaton, “Vietnam and Iraq in Japan: Japanese and American Grassroots Peace Activism“; Kageyama Asako and Philip Seaton, “Marines Go Home: Anti-Base Activism in Okinawa, Japan, and Korea“; Tanaka Nobumasa, “Defending the Peace Constitution in the Midst of the SDF Training Area.”

8 Lawrence W. Beer and Hiroshi Itoh, eds., The Constitutional Case Law of Japan, 1970 through 1990 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1996), 83-130; Toshihiro Yamauchi, “Constitutional Pacifism: Principle, Reality, and Perspective,” in Five Decades of Constitutionalism in Japanese Society, ed. Yoichi Higuchi (Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press, 2001); Port, Transcending Law, 129-130.

9 Eniwa Jiken Taisaku Iinkai, ed., Eniwa jiken: Jieitaihō ihan: kōhan kiroku 1, 2 (Sapporo: Eniwa Jiken Taisaku Iinkai, 1964), 1-3.

10 Eniwa Jiken Taisaku Iinkai and Hokkaido Heiwa Iinkai, eds., Eniwa wa kokuhatsu suru (Kyoto: Chōbunsha, 1967), 54-55.

11 Ibid., 90-91.

12 Eniwa Jiken Taisaku Iinkai, ed., Eniwa jiken 1, 2, p. 4. Although the English version of the Japanese constitution uses the term “war potential” to refer to senryoku, throughout this paper I use “war capability” to illuminate more clearly the military power the state possesses, and to contrast it to “defense capability” or bōeiryoku.

13 Ibid., 47.

14 John O. Haley, “Waging War: Japan’s Constitutional Constraints,” in Constitutional Forum, Vol. 14, No. 2, 2005, 28.

15 Ibid., 24-25; Port, Transcending Law, 95-100.

16 David Rodin, War and Self-Defense (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), 103-110; Yoram Dinstein, War, Aggression, and Self-Defense (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 83-91.

17 Watanabe Minoru, ed., Eniwashi-shi (Eniwa: Hokkaido Eniwa Shiyakusho, 1979), 515-516.

18 The following accounts of the Nozaki brothers’ experience is based on their statements and that of one of their lawyers at the fourth hearing on March 16, 1964. Eniwa Jiken Taisaku Iinkai, ed., Eniwa jiken 1, 2, 49-61.

19 Ibid., 57.

20 At the fifth hearing on March 18, 1964. Ibid., 105-107.

21 Deborah J. Milly, Poverty, Equality, and Growth: The Politics of Economic Need in Postwar Japan (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center, 1999), Ch. 7.

22 Thomas Havens, Fire Across the Sea: The Vietnam War and Japan 1965-1975 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987).

23 Vera Mackie, Feminism in Modern Japan: Citizenship, Embodiment, and Sexuality (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), Ch. 7.

24 Timothy George, Minamata: Pollution and the Struggle for Democracy in Postwar Japan (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center, 2001), Ch. 6 and 7.

25 Wesley Sasaki-Uemura, Organizing the Spontaneous: Citizen Protest in Postwar Japan (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2001).

26 Simon Andrew Avenell, Making Japanese Citizens: Civil Society and the Mythology of the Shimin in Postwar Japan (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010).

27 Immanuel Wallerstein, Geopolitics and Geoculture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), Ch. 5.

28 Hoshino Yasusaburō, “Heiwateki seizonken joron,” in Nihonkoku kenpōshi-kō: sengo no kenpō seiji, ed. Kobayashi Takasuke and Hoshino Yasusaburō. (Kyoto: Hōritsu Bunkasha, 1962), 3-25.

29 Watanabe Yōzō and Matsui Yasuhiro, eds., Eniwa Jiken (Tokyo: Rōdō Junpōsha, 1967), 49-50.

30 Eniwa Jiken Taisaku Iinkai, ed., Eniwa jiken kōhan kiroku 10 (Sapporo: Eniwa Jiken Taisaku Iinkai, 1967), 51-71. This final plea was also published in Fukase Tadakazu, Eniwa saiban ni okeru heiwa kenpō no benshō (Tokyo: Nippon Hyōronsha, 1967).

31 Eniwa Jiken Taisaku Iinkai, ed., Eniwa jiken kōhan kiroku 11 (Sapporo: Eniwa Jiken Taisaku Iinkai, 1967), 1-4.

32 Eniwa Jiken Taisaku Iinkai and Hokkaido Heiwa Iinkai, eds., Eniwa wa kokuhatsu suru, 217.

33 Fukase, Eniwa saiban ni okeru heiwa kenpō no benshō, 252.

34 On Japanese firms’ efforts to domesticate armament production, see Richard Samuels, “Rich Nation, Strong Army”: The National Security and the Technological Transformation of Japan (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1996).

35 The Japanese government has been launching defense buildup plans about every five years since 1958. In each plan, the government announces plans for the defense budget, fundamental defense policies, and the types of weapons to be developed over the next five years. On the Third Defense Buildup Plan, in addition to Samuels’s book, see Asagumo Shinbun Henshūkyoku, ed., Bōei hando bukku: Shōwa 50 nen-ban (Asagumo Shinbunsha, 1975), 13-20.

36 Naganuma is located in wet, low land. The community had been affected by a number of floods. See Naganumacho-shi Hensan Iinkai, ed., Naganumachō no rekishi, gekan (Hokkaido Naganumachō, 1962).

37 Hayashi Takeshi, Naganuma Saiban: Jieitai iken ronsō no kiroku (Tokyo: Gakuyō Shobō, 1974), 15-16.

38 Naganuma Jiken Bengodan, ed., Naganuma misairu kichi jiken soshō kiroku 1 (Sapporo: Hokkaido Heiwa Iinkai, 1970), 10-26.

39 Hoanrin kaijo shobun shikkō teishi mōshitate jiken,” attached to Naganuma Jiken Bengodan, ed., Naganuma misairu kichi jiken soshō kiroku 1, 1-17.

40 Ibid., 53-58.

41 “Shikkō teishi kettei ni taisuru sokuji kikkō mōshitate jiken,” attached to Naganuma Jiken Bengodan, ed., Naganuma misairu kichi jiken soshō kiroku 1, 1-50.

42 Naganuma Jiken Bengodan, ed., Naganuma misairu kichi jiken soshō kiroku 1, 26-37.

43 Ibid., 45-52.

44 Ibid., 75-77.

45 Summary of the testimonies of Genda Minoru (former Chief of Staff of the Air SDF) on October 9, 1970 and January 29, 1971, Ogata Kagetoshi (Chief of Staff of the Air SDF) on May 14, 1971, Uchida Kazutomi (Chief of Staff of the Maritime SDF) on September 30, 1971, and Nakamura Ryūhei (Chief of Staff of the Ground SDF) on November 25, 1971. Naganuma Jiken Bengodan, ed., Naganuma misairu kichi jiken soshō kiroku 2 (Sapporo: Hokkaido Heiwa Iinkai, 1972), 23-67, 129-185, 253-321, and 375-421; Naganuma Jiken Bengodan, ed., Naganuma misairu kichi jiken soshō kiroku 3 (Sapporo: Hokkaido Heiwa Iinkai, 1972), 481-541.

46 Testimonies of Hayashi on November 26, 1971, and Osanai on March 31, 1972. Naganuma Jiken Bengodan, ed., Naganuma misairu kichi jiken soshō kiroku 3, 579-581, 732-735, and 741-742.

47 Testimony of Osanai on March 31, 1972. Ibid., 720-724. Today, we know that Osanai’s fear was by no means irrational. Before its reversion to Japan, Okinawa was armed with nuclear weapons. Although nuclear weapons were removed from Okinawa when Japan regained sovereignty, it was recently revealed that President Nixon and Prime Minister Satō had made a secret agreement in 1969 that, even after its reversion, the United States could bring nuclear weapons to the prefecture in an emergency situation. See Yomiuri shinbun, evening edition, December 22, 2009. Moreover, George Packard has recently indicated that despite the Japanese government’s public insistence on the Three Non-Nuclear Principles, under a secret agreement, it allowed US ships and planes carrying nuclear weapons to stop at Japan. See Packard, “The United States-Japan Security Treaty at 50,” Foreign Affairs, March/April 2010.

48 The joint statement is available on the homepage of the US Embassy in Japan. On the US-Japan relations during this era, see Michael Schaller, Altered States: The United States and Japan since the Occupation (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), Ch. 12.

49 Testimonies of Yamada on July 16, 1971, and Takahasi on March 12, 1971. Naganuma Jiken Bengodan, ed., Naganuma misairu kichi jiken soshō kiroku 2, 342-343, 364-367, and 224-225.

50 Naganuma Jiken Bengodan, ed., Naganuma misairu kichi jiken soshō kiroku 5 (Sapporo: Hokkaido Heiwa Iinkai, 1973), 1315-1318.

51 Ibid., 1318-1320.

52 Ibid., 1351-1352.

53 The verdict of the Sapporo High Court is available on the database of judicial precedents on the court’s website. For the record of the trial, see Naganuma Jiken Bengodan, ed., Naganuma misairu kichi jiken soshō kiroku 6 (Sapporo: Hokkaido Heiwa Iinkai, 1975), and Naganuma misairu kichi jiken soshō kiroku 7 (Sapporo: Hokkaido Heiwa Iinkai, 1976).

54 Beer and Itoh, The Constitutional Case Law of Japan, 49-54.

55 Ibid. Port, Transcending Law, 129-131; Hidenori Tomatsu, “Judicial Review in Japan: An Overview of Efforts to Introduce U.S. Theories,” in Five Decades of Constitutionalism in Japanese Society, ed. Higuchi (Tokyo: Tokyo University Press, 2001). Although the Democratic Party took power in 2009, attitudes toward non-justiciable, political questions had been consolidated during the LDP era. Therefore it seems unlikely that the courts, particularly the Supreme Court, will drastically change their reluctance to judge the constitutionality of governmental acts anytime soon.

56 The verdict of the Supreme Court is available on the database of judicial precedents on the court’s website.

57 Tsurumi Shunsuke, “Nemoto kara no minshu shugi” in Nichijō no shisō: sengo Nihon shisō taikei 14, ed. Takabatake Michitoshi (Tokyo: Chikuma Shobō, 1970), 284-295. Tsurumi first published this article in Shisō no kagaku, July 1960.

58 Watanabe Yōzō. Seiji to hō no aida: Nihon-koku kenpō no jūgonen (Tokyo: Tyoko Daigaku Shuppankai, 1963), 7-11.

59 Fukase Tadakazu, Sensō hōki to heiwateki seizonken (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1987); Hoshino Yasusaburō, “Heiwateki seizonken kara kyōzonken e,” in Kenpō no kagakuteki kōsatsu, ed. Hoshino et al (Kyoto: Hōritsu Bunkasha, 1985); Yamauchi Toshihiro, Heiwa kenpō no riron (Tokyo: Nippon Hyōronsha, 1992).

60 The verdict and the explanation of its significance by a lawyer for the plaintiffs are available in Kawaguchi Hajime and Otsuka Eiji, “Jieitai no Iraku hahei sashidome soshō” hanketsubun o yomu (Tokyo: Kadokawa Shoten, 2009).