Japan, Britain and the Yellow Peril in Africa in the 1930s

Richard Bradshaw and Jim Ransdell

During the 1930s, a dramatic increase in Japanese exports to Africa and Japan’s growing influence in Ethiopia led many Europeans and South African whites to evoke the specter of the ‘Yellow Peril’ and to call for measures to halt Japan’s ‘penetration’ of Africa. Japan’s close ties with Ethiopia and her growing exports to South Africa were of particular concern. Japan and Italy were able to reach an agreement with regard to their conflict of interest in Ethiopia, but Japan’s relations with the British Empire suffered as a result of anti-Japanese sentiment in South Africa.

Growing Chinese economic and political influence in Africa has recently received considerable attention,1 but this is not the first time that the projection of Asian power into Africa has provoked great concern. In the 1930s, a rapid rise in Japanese exports to Africa and Japan’s close ties with Ethiopia invoked cries of the ‘Yellow Peril’ and led to efforts to stop Japan’s penetration of Africa.2 Barriers to Japanese exports were erected all over Africa to secure markets for the colonial powers of Europe, Britain in particular.3 With decline in European exports during World War I, the Japanese had been able to gain an economic foothold in countries such as the Union of South Africa.4 This growth of Japanese exports to southern Africa during the first decades of the 20th century coincided with the growth of South African economic nationalism, which, in turn, led to public hysteria among European competitors and domestic business interests over what was perceived as Japanese economic “dumping.”5 The conclusion of a “Gentleman’s Agreement” with Japan by Prime Minister Hertzog’s government in the 1930s further antagonized white South Africans who displayed widespread bi-partisan hostility to the arrangement. Later, following the Great Depression and South Africa’s gold standard crisis, the economic concerns of South African whites were compounded with worries over Japan’s political ambitions in Ethiopia.6

This became a matter of concern from Rome to Cape Town at the time of the Italo-Ethiopian crisis of 1934-35, during which Italy feared that Japan would provide military assistance to Ethiopia, were it attacked. Though this incident initially saw public outcry on both sides, it ultimately brought Italy and Japan closer together. The Italian and Japanese governments were able to overcome their clash of interests in Africa by reaching a compromise regarding their respective spheres of influence in Ethiopia and Manchuria. But for the British, the Japanese activities in Manchukuo (満州国) combined with the ongoing competition between the two over exports throughout Africa was a point of tension dividing the two former allies.

Rising Japanese exports to Africa

Although Britain’s trade with foreign countries was far greater than its trade with its colonies, its diminishing overseas sales were most apparent in its colonies.7 African consumers were particularly attracted to low-priced Japanese goods. While Japan maintained an adverse balance of trade with British dominions prior to the 1930s, it subsequently came to have a favorable exchange with them in the 1930s.8

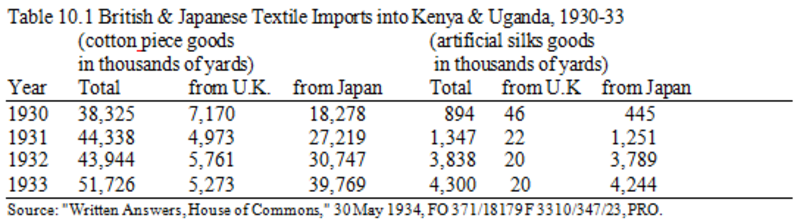

The most important new markets for Japanese goods in Africa were the British colonies of East Africa where, in most cases, free entry of Japanese goods was protected by treaty. As the following tables indicate, Japanese exports of cotton and rayon textiles subsequently came to constitute a serious threat to British textiles in East Africa.

British measures to curtail even the rather modest growth of Japanese trade with British West Africa particularly offended the Japanese.9 This was further exacerbated by the efforts of British allies, such as the French, to restrict the flow of Japanese goods into their colonies and dependencies such as Morocco.10 To the Japanese, it appeared clear that the British and other European colonial powers were selectively discriminating against Japanese goods. The erection of barriers to Japan’s exports throughout colonial Africa in places such as Portuguese Africa11 and Egypt12 thus led to further Anglo-Japanese alienation during a time when the world’s political climate was becoming ever tenser. Still, the greatest point of economic contention was South Africa.

Asian-South African relations before the Great Depression

Commercial contacts between Asia and South Africa were first stimulated by the founding of Dutch East India Company (DEIC) posts in both locations during the seventeenth century. The possibility of exporting animal skins from South Africa to Japan was one of the reasons DEIC employee Jan van Riebeeck offered for establishing a post in South Africa in 1652.13 Between the late seventeenth and early twentieth centuries, a small quantity of goods passed between Japan and South Africa in Dutch, British (after c. 1800), and Indian (after c. 1870) ships. However, the real turning point for South African-Japanese trade relations was World War I, during which Japanese trade with South Africa flourished as Japan replaced the European countries that had become entangled in the conflict on the continent.

Though imports decreased from their wartime boom to less than 4 million yen by 1920, this was still nearly ten times the value of the trade prior to World War I. By 1921 trade relations had deepened and the value of Japanese exports to the Union of South Africa was again experiencing substantial growth. By 1926, a combination of falling costs of cotton thread and favorable exchange rates gave Japanese goods a new opportunity in South Africa.14 Thus, late 1920s South African protectionists began to express concern over the extent to which Japanese exports of certain products (notably silk goods, cotton textiles, and clothing) had grown. Intent on stimulating the growth of South African industry, the Nationalist-Labor Pact government led by General Barry Hertzog, who served as prime minister of South Africa from 1924-1939, enacted a tariff reform in 1925. Further protective measures included anti-Asian legislation, such as the 1913 Immigration Act, which had provisions aimed against all Asians, but effectively prohibited Japanese from residing and doing business in South Africa. Troubled by this restriction, the Japanese Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce sent Magoichi Nunokawa (孫一布川) in late 1916 to negotiate an agreement that the 1913 Act would not apply to the Japanese, but the British government, which still deeply influenced South African policymaking, intervened to put an end to the negotiation. Although South Africa had gained considerable autonomy after the formation of the Union of South Africa in 1910, British influence, particularly in the realm of foreign policy, was still quite strong.

Growing fear of a ‘Yellow Peril’

The next decade, under PM Hertzog, saw the growth of discrimination in various forms while the Japanese still struggled to extricate themselves from the anti-Asian legislation. Hertzog’s election campaign of June 1929 focused on the Swart Gevaar or “Black Peril” and advocated increasing discriminatory policies on various fronts. However, in October 1930, South Africa began to feel the Great Depression. Between 1928/9 and 1932/315 the value of wool exports from the Union fell by over 70 percent. As discriminatory legislation restricted potential buyers, the Union’s need to attract businessmen who would purchase more wool dictated changes in policy.16

Accordingly, on 2 September 1930, the Union Ministry of Agriculture decided to permit Japanese wool purchasers to enter South Africa. Then, on 16 October 1930, the acting Japanese consul in Cape Town, Yamasaki Sakashige (山崎坂重) and acting external affairs secretary, W.G.H. Farrell, exchanged notes stating that Pretoria would, upon the recommendation of the Japanese consul, grant a temporary permit valid for one year to Japanese tourists, students, wholesale merchants and purchasers of South African goods to enter and reside in the Union. The document stated that, “no Japanese subject whose admission is recommended by the Consul for Japan in terms of this understanding will be served on arrival at a Union port with a notice declaring him to be a prohibited immigrant.”17

Criticism of what came to be known as the “Gentleman’s Agreement” began in March 1931 and continued throughout the summer, the overarching fear being that Japanese stores would soon proliferate throughout the country. When such concerns surfaced during debates in the Assembly on 5 July 1931, interior minister Dr. Daniel F. Malan, the leader of the Nationalist Party in the Cape, ridiculed the idea that the Union would be overrun by Japanese retail traders, factory employees and farm hands, but then disagreed with the critics of the treaty who argued that only Japanese wholesale buyers should be allowed admittance into the country.18

A few days later a letter in the Rand Daily Mail, a leading Johannesburg newspaper, charged that by the terms of the treaty

A Japanese wholesale firm may establish itself anywhere in South Africa (except the Orange Free State, where by statute, no Asiatics are permitted to live) and carry on business selling any class of goods, and utilising a hundred percent Japanese staff. As there is no law to prohibit a merchant who has a wholesale license from selling direct to the public, the Agreement means that these wholesale traders can do a retail business.19

The same critic mentioned that by the time of the last census, in 1921, there were already 98 Japanese residents in the Union. At present, he warned, “one of the biggest merchant princes of Japan is visiting us with an eye to establishing wholesale houses in this country.” The Japanese, he added, were busy “spying out the land.”20

Opposition leader General Jan Smuts voiced yet another objection to the treaty, asserting that “it would be quite impossible to keep out Asiatic immigrants once [the Union] had very large trade relations with the East.”21 His wife, Isie Smuts, also spoke out against the treaty. At a South African Party gathering she condemned it, saying

We are already having a good deal of trouble with the Indians in this country, and now the Government proposes to introduce a yellow race into South Africa, the strongest and most powerful yellow race in the world. Once they are in we shall never succeed in getting rid of them.22

The press also attempted to demonstrate exactly how the “dumping” of goods from Japan would damage local trade. After praising South Africa’s “flourishing and excellent boot and shoe industry,” a critic noted that Japanese shoes, or “plimsolls,” were “selling like hotcakes” after being landed at a cost of between 1s. 6d. and 2s. (c. $.50) a pair. The “poorer of the coloured folk” in Cape Town, he noted, were buying them for as little as 3s. (c. 75 cents) a pair. These “plimsolls” were threatening the sale of the locally made velskoen (untanned hide shoes) which sold for 5s. 6d. (c. $1.35) a pair.23

As this table indicates, Japanese imports also included growing quantities of clothing, another category of good which South African industry was attempting to provide. Japanese exports to South Africa were clearly increasing, but except for silk, they constituted only a small part of the goods entering the Union. Although the quantities as of 1929 did not represent a particularly large percentage of the Union’s overall imports, quantities in many categories had nearly doubled since 1926. Thus, South African industrialists feared imports of Japanese goods would continue to increase and that domestic industries would not be able to compete in the long run.

Japan’s acting consul in Cape Town, Mr. Hongō (本郷), made efforts to offset this rising tide of anti-Japanese agitation. In response to the rumors that the Japanese were setting up warehouses all over the Union, he asserted that not a single Japanese warehouse had been established during the nine months since the signing of the agreement. As for the question of commercial competition, Mr. Hongō placed the blame on the South African businessmen who, he claimed, competed unnecessarily among themselves.24

Still, complaints linking the treaty with increased Japanese imports frustrated members of Hertzog’s cabinet. The labor minister, Colonel Cresswell, commented that those people who had previously been so intent on the government’s not raising tariffs were now, for self-serving reasons, raising “a howl” about the treaty with Japan. Further complaints were then raised regarding “yellow standards of living” which, it was claimed, were at the root of the problem. In July 1931, at a public meeting in Johannesburg, a prominent lawyer and Parliament member, Colonel C. F. Stallard, a strong opponent of Asian immigration, claimed that there “had seldom been a matter which had struck deeper at the roots of the prosperity of South Africa.” The Union of South Africa “did not want [an influx of Japanese] people who could not be assimilated…and live in accordance with civilized standards.”25 In response to these criticisms, interior minister Malan explained, once again, that the Japanese treaty was unrelated to the rise in Japanese imports.26

Nevertheless, this link endured in the minds of the public and the government found itself having to explain the disadvantages of increasing tariffs. When the “serious effects to South African industries created by the importations of Japanese rubber-soled shoes,” arose during Parliamentary debates, the minister of mines and industries remarked that the government had no desire to increase the 30 percent protective duty already in place.27

General Kemp, the agricultural minister, defended the treaty by noting that prices for many South African consumers would drop. He also emphasized that the treaty could lead to the capture by the Union of new markets in the East and prompt the Japanese to buy more wool.28 Whatever else was said, it was really this hope that the Japanese would purchase more wool which lay behind the conclusion of the controversial treaty. And yet, before the year was out, Hertzog’s government would elect not to follow Britain in abandoning the gold standard, a decision which reduced Japanese demand for South African wool. Thus what the cabinet had hoped to achieve was undone by its reluctance to allow the South African pound to fall in value.

The gold standard crisis in South Africa

The initial uproar over the Japanese Treaty died down during the latter half of 1931, but the underlying anger remained. Thus, following Great Britain’s September 1931 decision to discontinue use of the gold standard, when changes in the relative value of both Japan’s and South Africa’s currencies made Japanese goods even cheaper and South African goods more expensive, the stage was set for a new outbreak of anti-Japanese demonstrations. These feelings intensified over the next fifteen months as Hertzog and his ministers ignored growing domestic opposition and refused to allow the Union to follow Britain in abandoning the gold standard. This had a devastating impact on foreign demand for export-dependent agricultural products, wool in particular. On the other hand, Australia, which produced three times as much wool as the Union, and which was Japan’s primary supplier, left the gold standard as early as February 1931. By the end of that year and in early 1932 the Union’s wool became almost twice as expensive as that of Australia’s, in terms of British pounds.29

By mid-1932, after Japan abandoned the gold standard on 13 December 1931, the value of the Japanese yen had dropped to half its former level and exports began to rise sharply.30 Thus, facing acute financial and political crises, finance minister Havenga announced the abandonment of the gold standard by the Union on 28 December 1932. Nevertheless, imports of Japanese goods continued to climb.31

Renewed outbursts of Anti-Asian agitation

In 1933 the value of imports from Japan rose higher than ever before, to over 26.7 million yen (c. $6.85 million). This dramatic increase sparked a new wave of anti-Japanese demonstrations: politicians called for action, newspapers were filled with articles advocating different measures to be taken, and eventually a boycott was initiated.

In September 1933, speakers at the Union’s Chamber of Commerce voiced their hostility to the rise in Japanese imports. One speaker reminded his audience that the government had not addressed sufficiently the importation of Japanese footwear until some “seven million pairs of rubber and canvas shoes were actually in the country and the lower end of the industry was threatened with extinction.”32

Unlike the threat to domestic industry posed by Japanese shoes, due to measures taken by Hertzog’s government in response to this agitation, and its abandonment of the gold standard, the price of gold began to rise in September 1933,33 and wool prices were up 33 percent from the year before.34 Concern remained, however, about competition with Japanese products in foreign markets. Coal from Japan, which was mined in Manchuria, sold in Singapore and elsewhere for a lower price than South African coal. A Johannesburg newspaper estimated that South African coal would have to be produced for 4s. (c. .83 cents) per ton “at the pit’s mouth” in order to compete with Japanese coal. After leaving the pit, the argument continued, the coal had to be sent to the coast and shipped to Singapore and yet still sold for 16s. (c. $3.32) per ton or less; and “even then the Japanese are in a position to undersell” South African coal.35

The fears of South African whites were not only economic. Since the early 20th century, multitudes of Japanese emigrants had refueled in South African ports on their way to settle in Brazil. Having borne witness to this, South African whites were particularly aware of the Japanese government’s desire to find outlets for what it termed Japan’s “excess population.” Thus any suggestion that Japanese interests might obtain land or concessions anywhere in Africa or Asia, whether in neighboring Swaziland, in Ethiopia, or in East Asia, came to elicit strong reactions from South African whites. Japanese encroachments in Africa were viewed by South African whites, in the end, as threats to white supremacy on the continent.

In September 1931 concern in South Africa grew upon hearing news of Japan’s invasion of Manchuria. “It is practically certain that the Japanese military and naval authorities possess a ready‑made plan to people the empty spaces here and in Australia,” it was reported.36 The Rand Daily Mail’s headlines on 24 September were “3 WHITES KILLED – By Japanese in Mukden – ‘TO ABSORB CHINA’ – Step to World Domination.”

Fears were exacerbated by the pronouncements of certain military enthusiasts and pan-Asianists in Japan. In a book entitled Japan Must Fight Britain, for example, lieutenant-commander Ishimaru Tōta (石丸藤太) of the Japanese navy had discussed the strategic importance of the Cape, arguing that “it would be far wiser for Britain to concentrate on protecting the Cape route” instead of the Mediterranean route and that “Great Barriers have grown up between England and her children, [including] South Africa…”37

The sympathy for Japan expressed among non-white South Africans and their sympathizers further troubled white South Africans. John Henry Baynes of Johannesburg, describing himself as a European with a “Cape Colored wife” and “leader of the African Proletariat Party,” wrote a letter to the Japanese foreign ministry in April 1931 in which he condemned white South African hostility towards the “Japanese Commercial Treaty” and praised the efforts of the Japanese to defend the rights of their colored brothers.[38

The ‘Yellow Man’ Looks On

The apprehension of many South African whites was expressed when a South African, Hedley Arthur Chilvers, published The Yellow Man Looks On in 1933.39 In this book, Chilvers argued that Anglo‑Dutch reconciliation was necessary, and even advocated black‑white cooperation in the Union, because of the Japanese threat. The book voiced support for the coalition or United Party government formed by Hertzog and Smuts in 1933. Just as the “Black Peril” provided a slogan for Hertzog’s electoral campaign in 1929, the specter of a “Yellow Peril” provided some justification for Hertzog’s controversial decision to join forces with Smuts in 1933. In his introduction to the book Abe Bailey wrote: “If the white races in Southern Africa can only agree to work together…they will continue to enjoy the protection of the British navy.”

|

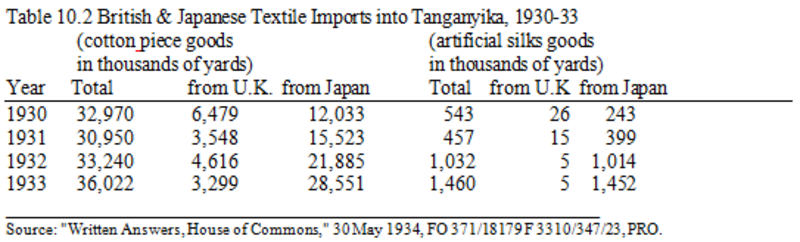

A depiction of yellow peril hysteria in a postcard from the early 1900s. Source |

Publication of Chilvers’ book in late 1933 coincided with the first reports that the Japanese government was negotiating the purchase of a large cotton-growing plot and other commercial concessions with the Ethiopian government.40 These rumors were taken seriously enough to provoke debate in South Africa’s parliament41 and prompted diplomatic and military intelligence correspondence.42 Japan’s perceived closeness with Ethiopia soon became a matter of worldwide concern as the Italo-Ethiopian conflict loomed. Thus, in the midst of Japan’s formidable escalation of trade its political influence on the continent of Africa became a matter of grave concern to all the European colonial powers and intensified white South African fears of the Yellow Peril.

Japan’s attempt to increase imports of South African wool

The cry of “Yellow Peril” would have incited less fear among white South Africans had the rapid increase in Japanese exports been complemented by an increase in Japanese purchases of raw wool from the Union; but this was not the case. However, during 1933 the prospect that the Japanese might become important wool buyers seemed to improve.43 Though South African wool remained more expensive than Australian wool, the Japanese were gradually increasing their purchases of South African wool in hopes of capturing a greater market for their exports.44

A Japanese foreign ministry official, Mr. Shudō (首藤), visited South Africa early in 1934 to seek a solution to the intensifying trade dispute. Shudō encountered strong anti-Japanese sentiment in South Africa. He and his colleagues were treated very discourteously at times during their stay in the Union, once being excluded as “Asiatics” from a cinema, and suffered other humiliating discrimination.45

Nevertheless, shortly after returning to Tokyo, Shudō outlined to the commercial counselor at the British Embassy, George B. Sansom, the steps the Japanese government had taken to improve the situation. Shudō explained that although Japan had promised at the time of the “Gentleman’s Agreement” (1930) to attempt to increase its purchase of South African goods, raw wool in particular, it had failed to purchase more than 10,000 bales per annum during any year since then.46 In order to alleviate some of the tension, Shudō advised the Japanese government to increase purchases of South African wool.

The Japanese government then arranged with the Association of Woolen Industries and others to immediately increase imports of wool from South Africa, agreements which were partially successful. Japan advanced in the rank of exporters to South Africa. By 1935 she was in fourth place, behind Great Britain, the United States, and Germany. Japan rose to second place, after Germany, in 1936-7.47 But as a Japanese study reported in 1937:

South Africa’s policy to promote the buying of wool was far less successful than expected. At the same time the South African market was flooded by Japanese products. In contrast, imports of European goods, especially British ones, were declining sharply and the pro-British element in South Africa thus strongly attacked the failure of the “Gentleman’s Agreement” with Japan and the fact that Japan purchased such a small quantity of South African wool. In addition, every newspaper has been running articles on Japanese insincerity and on the unfair competition of Japanese traders. Anti-Japanese sentiment is increasing dramatically as the mood of the people grows more hostile to Japan and its products.48

Thus Japanese expansion in Africa evoked a strong reaction among many white South Africans in the 1930s. Japanese commercial development threatened the interests of British and South African manufacturers alike. Furthermore, Japanese ambitions were not, it appeared, limited to an increase in exports. By the early 1930s some South African whites feared that the Japanese harbored political ambitions in the African continent, and perhaps even colonial intentions. Although Japan’s economic presence posed the greatest threat to white South Africans domestically, the growing closeness of Japanese-Ethiopian relations was another source of uneasiness.

Japanese-Italian relations before the Italian invasion

Although the economic dimension of Japanese-Ethiopian relations during the interwar period was far less important than the political aspect, their trade relations actually predated those of South Africa. It was during the 17th century, under the Tokugawa Shogunate, that the first diplomatic exchange of gifts between the Japanese government and an African government took place. In 1675 Khodja Murad, an “ambassador of several Ethiopian kings and a merchant in his own right,” sent two zebras to the Japanese government from Batavia. The Japanese government not only recognized this gesture but sent “10,000 taels [ounces] of silver and thirty Japanese garments” to Khodja in return.49

As has been noted, by the 20th century the Japanese had begun trading all over Africa, much to the alarm of the British and other colonial powers. However, it was Italy whose relations with Japan suffered the most severe strain in the months before the Italian invasion of Ethiopia in October 1935. Part of the reason for this was the worldwide commercial competition between the two nations.50 In the early 1930s their trade rivalry encompassed Latin America and the Balkans as well as Africa and Asia. Italians resented Japan’s capture of ever-increasing market shares around the world at the expense of Italian exports. Moreover, since both countries specialized in the export of low-cost textiles they were often in direct competition with one another.

As will be seen, the restoration of cordial relations between Japan and Italy, and their conclusion of an eventual alliance, only became possible after the two countries reached an agreement regarding their respective positions in Manchuria and Ethiopia.

Japanese official response at the outset of the conflict

Though the Ethiopian Crisis would eventually lead to the formation of bonds between Japan and Italy, at initially brought the two countries into conflict and placed great strain on their relations. The spark which lit the fire was a November 1934 border dispute between Ethiopia and Italian Somaliland.51 In reaction to this incident, on 24 December, the Ethiopian Chargé d’Affaires in Rome, Negadras Ghevre Yesus, asked Sugimura Yotarō (杉村陽太郎), the Japanese ambassador to Italy, if the Japanese government would be willing to supply arms to the Ethiopian government.52

Formerly Japan’s ambassador to the League of Nations,53 Sugimura was a member of Japan’s controlling faction, an official who, like his superiors, undoubtedly valued the Italo-Japanese relationship more highly than the Japanese-Ethiopian relationship. Sugimura explained to Ghevre that he had no authority to commit Japan to providing weapons to Ethiopia. He emphasized however, that Japan was interested in expanding their economic ties.54

When Sugimura met with Premier Mussolini in mid-July 1935, he reportedly assured Mussolini that Japan had no intention of supplying military aid to either party, even if war were declared.55 But almost simultaneously, on 18 July, London papers reported foreign minister Hirota Koki (広田弘毅) , as having suggested that Japan would act in defense of its interests and nationals in Ethiopia. This, it was expected, would stiffen Ethiopian resolve to resist Italian demands.56 Sugimura’s unqualified assurances to Mussolini were clearly at odds with the more calculated and ambiguous diplomatic stance taken by Hirota and Prime Minister Okada Keisuke (岡田啓介).

Following this, Sugimura was questioned on the content of his discussion with Mussolini by a representative of Rengo news services in Rome. Sugimura explained that he had told Mussolini that Japan was watching the crisis carefully in light of its economic interests in Ethiopia. He then attempted to refute rumors aired in the press regarding the possibility of Japan’s intervention in the conflict.57

Italian reaction to the Sugimura affair

The Italian ambassador to Japan, Giacinto Auriti, went to the Foreign Office on the afternoon of 19 July to inquire into the reason for the contradictory statements issued by Japanese officials. Hirota assured him that the Japanese wished for a peaceful solution, but that Sugimura’s statement of absolute assurance did not reflect the Foreign Office position. 58

Ambassador Auriti then drew attention to anti-Italian articles which had appeared in the Japanese press. In response, the same evening, a spokesman for the Japanese Foreign Minister, Amau Eijiro (尼羽英治郎), called on Luigi Mariani, counselor at the Italian Embassy in Tokyo, and reminded Mariani that a 6 July article in the Italian press had claimed that Ethiopia was violating the Italo-Ethiopian treaty of 1928 by purposefully favoring Japanese goods in order to stifle Italian influence in East Africa.59 Amau further pointed out an Italian article, dated 13 July, which stated that although Japan had occupied much of China, the anti-war Kellogg-Briand Pact was not yet dead.60 The Kellogg-Briand Pact of 1928, which renounced war as an instrument of national policy, was signed by Japan. Since Italy was on the verge of invading Ethiopia it was obviously hypocritical to remind Japan that it was a party to this ineffective pact which, in any case, was backed by little more than the threat of public disapproval were any of its 65 signatory nations to resort to war.

Still, Mariani continued to assert that the import of Japanese goods into Ethiopia breeched the Italo-Ethiopian Treaty of 1928 because the treaty had stipulated that Ethiopia would “welcome Italian products.” Amau replied that he found it hard to understand why Ethiopians or Japanese should be blamed for importing Japanese products on account of a treaty which stipulated only that Ethiopia would welcome Italian products.61

Shortly thereafter, when report of the Japanese Foreign Office’s denial of Sugimura’s statements reached Rome, it caused an uproar. Faced with contradictory statements, Italy chose to ignore the more threatening stance of the Foreign Office in favor of Sugimura’s initial pledge of neutrality.62 Thus, Rome announced that they expected Japan had no political interest in Ethiopia and would remain neutral if war broke out.63 Encouraged by the Italian government, the Italian public began to demonstrate dissatisfaction with Japan. On 22 July the Japanese Embassy in Rome was surrounded by six policemen and “numerous Fascist Blackshirts.” All the leading Italian newspapers then ran front-page stories examining Japanese policy towards Ethiopia. Some asserted that Japan was attempting to become a champion of both the yellow and black races.64 Others accused Japan of trying “to launch a big economic offensive against Europe” via the Red Sea and the African continent. They labeled the perceived expansion of Japanese imperialism worldwide by means of commercial “dumping” as a “peril to the white race.” An article by Virginio Gayda entitled “The Cry of Solidarity of the Yellow with the Blacks” in the widely-read Giornale d’Italie declared that:

Japan must not think that her methods of imperial conquest and violation of the territorial and national rights of peoples claiming standards of civilization much older and more refined than their own are ignored or misunderstood by the civilized nations of the world …However, there are some fixed points on the globe where such a policy is futile.65

Gayda maintained that Japan deliberately left the League of Nations in order to pursue her territorial ambitions in China, “whose civilization cannot be compared with that of Ethiopia.”66 Gayda seemed to imply that Japan’s aggression towards a ‘civilized’ country was more upsetting than Italy’s ‘civilizing mission’ in Africa.

Italian animosity continued, and, on 25 July, anti-Japanese demonstrations were reported in Milan, Genoa, Turin and Bologna. A newspaper founded by Mussolini, the Popolo d’Italie, argued that Japan’s new attitude towards the Italo-Ethiopian conflict completely contradicted the claim that Japan had no political interest in Ethiopia. It linked Japan’s sympathy for “poor Ethiopia” to Japan’s “unlimited political and economic expansion in Africa as a new hope for campaigning against Europe.” The Messagero asked why Japan could not stay out of the conflict and charged the Japanese with “hypocrisy, double-dealing and bad faith.”67 No anti-Japanese demonstrations took place in Rome, but police and Black-shirt guards were maintained around the Japanese Embassy.

The following day, 26 July, the anti-Japanese campaign by Italian newspapers suddenly ceased. There were still articles critical of Japanese activities in China, but the “virulent attacks of the previous two days” were noticeably absent.68 The press campaign against Japan did not in fact die out but rather, for a few days, overlapped with a new campaign against Britain. Britain had superseded Japan as Italy’s number-one-enemy. The reason for this can be discerned from an editorial in the Tevere which suggested that Britain would be faster than Japan to rush contraband arms to the Red Sea, to which Italy might respond with a “salvo of cannon.”69

Although the anti-Japanese campaign in Italian newspapers died down, the same day an estimated 15,000 demonstrators in Rome converged on the center of the city at midnight, many carrying banners and cartoons attacking Japan, Britain, and Ethiopia. The number of special carabinieri (riflemen) assigned to protect the Japanese and British embassies was strengthened to 200, compared to the previous allotment of two per site.70 The demonstrations were clearly not spontaneous. They appeared instead to have been carefully staged to send strong messages to Japan and Britain. When a huge crowd gathered near the Foreign Office on 25 July, for example, they were “harangued” by the secretary of the Fascist Party, who called for Italian expansion.71

By August it became increasingly clear that the British would not stop the Italian invasion of Ethiopia, and the Japanese government apparently saw no point in antagonizing Italy any further. When Auriti again questioned the Japanese government in mid-September about its position, vice foreign minister Shigemitsu Mamoru (重光葵) replied that since Japan’s withdrawal from the League of Nations it had adopted the principle of non-intervention in European political affairs not connected with East Asia. As long as the rights of Japanese were not endangered, Japan would remain neutral and watch developments closely.72

Japanese public opinion and the Italo-Ethiopian War

In contrast to the cautious, realpolitik stance of Japan’s leaders toward the conflict, important segments of the Japanese public felt that Italy’s aggression should be unequivocally condemned, if not forcibly prevented, by Japan. Support for the Ethiopian cause came primarily from right-wing patriotic organizations and allied factions within the military and the government bureaucracy, but also from a large number of newspaper reporters and the public at large.

This is illustrated by the coverage of the conflict by The Osaka Mainichi and its English version, as well as the Tokyo Nichi Nichi.73 Even before the Italian invasion, the Osaka Mainichi hired three Japanese residents in Ethiopia as special correspondents. In addition, journalists in London, Berlin, and Moscow were instructed to cover the “European repercussions” of the war and the paper’s New York reporter was even sent to Africa on a special mission. Finally, the services of “all the correspondents of world renown” were engaged to cover the war.74

The August 1935 mission to Ethiopia of the Osaka Mainichi‘s New York reporter, Wada Dengoro, is particularly noteworthy. News of his intention to negotiate a contract with the Ethiopian government for the Osaka Mainichi to broadcast to Ethiopians became a source of concern as far away as the Union of South Africa. The Union’s Defense Department feared that “if the Japs get a footing in Ethiopia of any kind, there will be no saying how far their influence will extend.”75

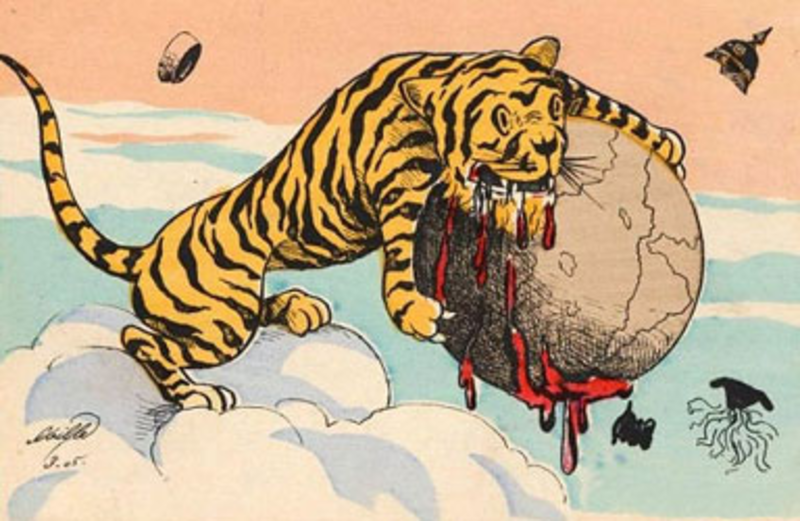

During this period, Japanese-Ethiopian relations were strong enough that a marriage between an Ethiopian prince and a Japanese woman was arranged. [Left] Kuroda Masako (proposed marriage between Araya Abeba of Ethiopia and Kuroda Masako of Japan) [Right] At the home of Mr. Sumioka. Front row, right to left: Araya Abeba, Foreign Minister Herui, Lij Tafari, and the interpreter, Daba Birru. In the back row are Mr. and Mrs. Sumioka. Picture taken from Herui’s Dai Nihon. “Marriage Alliance: The Union of Two Imperiums, Japan and Ethiopia?” Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Florida Conference of Historians, (Gainesville, FL: April 1999).

Back in Japan, a meeting of the Ethiopian Society of Osaka had been held at Hotel New Osaka on 22 July. Many of the attendees had either visited Ethiopia or had contact with Ethiopian Foreign Minister Herui during his visit to Japan in 1931, the year following the signing of a treaty of Friendship and Commerce between the two nations. Some speakers, such as the consul in Osaka, Yukawa Chusaburō(湯川忠三郎), stressed the similarities between Ethiopia (Abyssinia) and Japan. Others, such as the executive director of the Osaka-based Africa Traders’ Association, Yamazoe Shinkichi (山添新吉), spoke for commercial interests, reminding the gathering that over 50 percent of Ethiopia’s imports of cotton cloth and piece goods came from Japan.76

Popular support reached a fever pitch as money, letters, and applications from Japanese wanting to fight for Ethiopia flooded the honorary consulate in Osaka. Herui described a similar situation in Addis Ababa, as applications from Japanese, some written in blood, arrived en masse. Weeks later, Yukawa, the honorary consul, attempted to secure passports for four Japanese citizens wishing to enlist in Ethiopia’s flying corps. Another Japanese commander had offered the volunteers the use of two planes. One of the volunteers was Yasujiro Kita, a 28-year-old Japanese living in Berlin. Concerning the influx of applications, Yasujiro declared, “I am proud of the Japanese spirit of chivalry. I cannot remain idle in face of the news of the Italo-Abyssinian conflict as long as Japanese blood runs in my veins.”77 Despite this patriotic fervor, Tokyo did not allow any Japanese to participate, and Ethiopia’s consul rejected all applications.78

Japanese leaders, struggling to maintain control of policy, became alarmed as public support for Ethiopia exploded. They decided to clamp down on the activities of radical groups like the Amur River Society (黒龍会). Police raids in the wake of these pro-Ethiopian activities reduced this society to a shadow of its former self.79 The Home Ministry’s crackdown on the pro-Ethiopian activities of patriotic societies was one manifestation of the controlling faction’s assertion of power at this critical juncture. Finally, in February 1936, the failure of a coup by the Imperial Way Faction (皇道派) further strengthened the hand of government leaders who proceeded to ally Japan with Germany and Italy.

Manchukuo (Manchuria) and Ethiopia

Following this, on 12 May 1936, with the Japanese government firmly in control of foreign policy, Auriti, called on vice foreign minister Horinouchi Kensuke (堀之内健介) to notify the Japanese government of Italy’s annexation of Ethiopia and to promise that Japanese interests would be respected.80 Then, on 27 June foreign minister Arita cabled Sugimura in Rome that “while a unilateral recognition of the Italian occupation of Ethiopia would be in bad taste…the actual situation in Ethiopia should be recognized as presenting a fait-accompli to all governments.”81 Reluctant to take the lead in affirming this controversial acquisition, Japan delayed recognition and negotiated with Italy over the new few months.

Finally, in mid-October, 1936, Count Ciano, then Italian Foreign Minister, indicated to Sugimura that Italy would be willing to establish a legation in Manchukuo if Japan retained its Legation in Ethiopia.82 The Japanese government then asked for assurances that there would be no discrimination against Japanese imports in the new Italian protectorate. In response, Ciano indicated that he preferred not to exchange formal notes regarding such an arrangement at that time.83

Shortly thereafter, however, on 25 November, the Japanese Privy Council ratified the Anti-Comintern Pact, which served to remove any further reluctance on Italy’s part to solidify their hitherto informal agreement. On 2 December 1936 Japan and Italy thus exchanged notes whereby the former recognized Italy’s annexation of Ethiopia and the latter granted formal recognition to Manchukuo.84

Despite the strong undercurrent of support in Japan for Ethiopia, the Japanese government retained power throughout this period of crisis in Italo-Japanese relations and avoided alienating Italy. As Japan moved further away from its former ally, Great Britain, Japanese leaders were acutely aware of the need to protect their nation from international isolation by cultivating closer ties with alternative European powers. Italy, likewise, found itself in need of friends after worldwide condemnation of its invasion of Ethiopia. Japan and Germany provided natural allies in such circumstances.

Conclusion

Japanese intrusion into the “white man’s paradise” of Africa fueled concern over the “Yellow Peril” in Great Britain, South Africa and Italy. In South Africa, this anxiety was sparked by intensifying opposition to the “Gentleman’s Agreement” during the early 1930s as imports from Japan rose, and as Japanese purchases of South African wool failed to grow. Anti-Japanese sentiment within the Union in fact became so widespread that the Japanese government eventually decided to take measures, in cooperation with Japanese business, to assure greater purchases of South African wool. These measures were successful to some extent, Japan becoming the second largest buyer of South African wool by 1937. Only during that year, however, was the trade balance in the Union’s favor. It was a persistent trade imbalance in favor of Japan, together with direct competition between Japanese and South African goods, and the fact that the Japanese political as well as economic influence appeared to be growing rapidly on the African continent, which strained relations between Japan and South Africa as well as between Japan and the British Empire.

Japan’s leaders again faced with a difficult choice with the outbreak of the Italo-Ethiopian conflict. Since Japan’s occupation of Manchuria in 1931 it was increasingly cast in the role of an aggressive power and felt a growing sense of isolation from other powers with imperial ambitions. Japanese official response throughout the conflict was thus guarded and non-provocative, though their ambiguity angered the Italians. Finally, after the Italian government notified the world of its annexation of Ethiopia, the Japanese managed to reach an agreement with Italy by which it would grant recognition to Manchukuo and “most favored nation status” to Japan in Ethiopia in exchange for Japan’s recognition of Italy’s annexation of Ethiopia. This quid pro quo helped to bring the two power into diplomatic, and eventually military, alliance.

Richard Bradshaw is a professor of history and international relations at Centre College, Kentucky. His dissertation focused on Japanese-African relations prior to World War II and he has written several articles on this topic.

Jim Ransdell is a history and East Asian Studies major at Centre College, Kentucky. He co-authored an article in the 2010 edition of the Southeast Review of Asian Studies (SERAS) on Japanese-South African relations in the prewar period and is currently working on a book on Japanese-African relations.

Recommended citations: Richard Bradshaw and Jim Ransdell, ‘Japan, Britain and the Yellow Peril in Africa in the 1930s,’ The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 9, Issue 44 No 2, October 31, 2011.

Notes

1 See Barry Sautman and Yan Hairong, “Trade, Investment, Power and the China-in-Africa Discourse,” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus 53, 2 (28 December 2009).

2 Studies of the ‘Yellow Peril’ include Jenny Clegg, Fu Manchu and the Yellow Peril: the Making of a Racist Myth (Stoke-on-Trent: Trentham 1994): 1-36; Roger Daniels, “The Yellow Peril,” in The Politics of Prejudice: The Anti-Japanese Movement in California and the Struggle for Japanese Exclusion (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press 1999); Heinz Gollwitzer, Die Gelbe Gefahr: Geschichte eines Schlagworts: Studien zum Imperialistischen Denken [The Yellow Peril: History of Catchphrases: Study of Imperialist Thought] (Göttingen, Germany: Hubert & Company 1962); Yorim Hashimoto, Primary Sources on Yellow Peril, Series I: Yellow Peril Collection of British Novels, 1895-1913, 7 vols (Tokyo: Edition Synapse 2008); Sukehiro Hirakawa, The Yellow Peril: Past and Present (Washington, D.C.: The Woodrow Wilson Center 1985); Gary Hoppenstand, “Yellow Devil Doctors and Opium Dens: A Survey of the Yellow Peril Stereotypes in Mass Media Entertainment,” in Christopher D. Geist and Jack Nachbar, eds., The Popular Culture Reader, 3rd ed (Bowling Green, OH: Bowling Green University Popular Press 1983): 171-185; Wang Jiwu, ‘His Dominion’ and the ‘Yellow Peril’: Protestant Missions to the Chinese Immigrants in Canada, 1859 – 1967 (Waterloo, Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press 2006); John F. Laffey, “Racism and Imperialism: French Views of the ‘Yellow Peril’: 1895-1919,” in Imperialism and Ideology: An Historical Perspective (Montreal, Canada: Black Rose Books 2000); Ute Mehnert, Deutchland, Amerika und die ‘gelbe Gefahr’: zur Karriere eines Schlagworts in der Grossen Politik, 1905-1917 [Germany, America and the ‘Yellow Peril’: The Career of a Catchphrase in Big Politics, 1905-1917] (Stuttgart: Steiner 1995); Jacqui Murray, Watching the Sun Rise: Australian Reporting of Japan, 1931 to the Fall of Singapore (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books 2004); Yuko Naka, The Black Savage and the Yellow Peril: The Differing Consequences of the Radicalization of the Black’s and Japanese in Canada, M.A. Thesis, University of Western Ontario 1997; Greenberry G. Rupert, The Yellow Peril: or, The Orient vs. the Occident as Viewed by Modern Statesmen and Ancient Prophets (Choctaw, OK: Union Publishers 1911); Richard A. Thompson, The Yellow Peril, 1890-1924 (New York: Arno Press 1978).

3 On fears of Japanese influence in Africa, see Richard Bradshaw, “Japan and European Colonialism in Africa, 1800-1937,” Ph.D. diss, Ohio University (1992); Ethel B. Dietrich, “Closing Doors on Japan,” Far Eastern Survey 7:16 (10 August 1938): 181-186; Katsuhito Kitagawa, “Japan’s Economic Relations with Africa between the Wars: A Study of Japanese Consular Reports,” African Study Monograph 11:3 (December 1990): 25-141; Kitagawa, “Japan’s Trade with Colonial Africa in the Interwar Period,” Paper presented at the 32nd Annual Meeting of the African Studies Association (Atlanta, GA: November 1989); Takashi Okakura, Nihon to Afurika: Meiji Ishin Kara Dainiji Sekai Taisen Made [Japan and Africa: from the Meiji Restoration to the Second World War] (Tokyo: Dobun-kan 1992); Frederick V. Meyer, Britain’s Colonies and World Trade (London: Oxford University Press 1948); Jun Morikawa, Japan and Africa: Big Business and Diplomacy (London: Hurst & Co; Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press 1997); Morikawa, “The Myth of Japan’s Relations with Colonial Africa, 1885-1960,” Journal of African Studies 12:1 (1985): 39-46; Phillips P. O’Brien, The Anglo-Japanese Alliance, 1902-1922 (London: Routledge Curzon 2004); Sara Pienaar, South Africa and International Relations Between the Two World Wars: The League of Nations Dimension (Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press 1987); Arthur Redford, Manchester Merchants and Foreign Trade, Volume 2, 1850-1939 (Manchester: The University of Manchester Press 1956); Andrew Roberts, “Introduction,” in Andrew Roberts, ed., The Colonial Moment in Africa: Essay on the Movement of Minds and Materials 1900-1940 (Cambridge: University of Cambridge Press 1990); Ann Trotter, Kenneth Bourne, Donald Cameron Watt, eds., Great Britain, Foreign Office, British Documents on Foreign Affairs: Reports and Papers from the Foreign Office Confidential Print, Part 2, From the First to the Second World War, Series E, Asia, 1914-1939, 50 vols, (Bethesda, MD: University Publications of America 1991-1996), cf. Vol. II

4 On Japanese-South African Relations see, Chris Alden, “The Changing Contours of Japanese-South African Relations,” in Chris Alden and Katsumi Hirano, eds., Japan and South Africa in a Globalising World: A Distant Mirror (London: Ashgate 2003): 7-24; Kweku Ampiah, The Dynamics of Japan’s Relations with Africa: South Africa, Nigeria and Tanzania (London: Routledge 1997); Miriam S. Farley, “Japan Between the Wars,” Far Eastern Survey 8:21 (25 October 1939): 243-248; Tetsushi Furukawa, “Japanese Political and Economic Interests in Africa: The Pre-War Period,” Network Africa 7:14 (1991): 6-8; Gaimushō Tsū Shō Kyaku [Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Department of Commerce and Trade, Second Section], “Afurika Keizai Jijō Tenbō” [The Economic Situation in Africa and its Potential], (1932); Great Britain Public Records Office, Francis O’Meara to Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, 31 July 1934, London, FO 371/18173 F 5304; Great Britain Public Records Office, Sir H.F. Batterbee to Sir George Mounsey, 1 August 1934; C.T. Te Water to J.H. Thomas, 23 May 1934; Staff Officer (Cape Town Intelligence) to Director of Naval Intelligence (Admiralty), 23 May 1934; P. Lieschin to J.H. Thomas, 15 March 1934, London: FO 371/18188. B; Great Britain Public Records Office, (London): FO 371/18173 F 5304; Katsuhito Kitagawa, “Political and Economic Determinants of Japan’s Ties with Eastern and Southern Africa: An Historical Overview,” Paper presented at the 35th Annual Meeting of the African Studies Association, (Seattle, WA: November 1992); Kitagawa, “Sen Zen Ki Nihon no Minami Afurika e no Keizaiteki Kanshin: ‘Bōeki Zasshi’ no Chōsa ni Motozuite” [Japanese Economic Interest in South Africa during the Prewar Era: A Consideration of ‘Trade Journal’ Reports], Shakai Kagaku Kenkyū Nenpō [Annual Social Science Research Reports] 22 (March 1992): 172-83; William G. Martin, “The Making of an Industrial South Africa: Trade and Tariffs in the Interwar Period,” The International Journal of African Historical Studies 23:2 (1990): 59-85; Mitsubishi Economic Research Bureau, Japanese Trade and Industry: Present and Future (London: Macmillan 1936); Jun Morikawa, Minami Afurika To Nihon: Kankei No Reikishi, Kōzō, Kadai [South Africa and Japan: The History, Structure and Problematic (Nature) of their Relations] (Tokyo: Dobun Kan 1988); Morikawa, “The Anatomy of Japan’s South African Policy,” The Journal of Modern African Studies 22:1 (March 1984): 133-141; J. Forbes Munro, Africa and International Economy, 1880-1960: An Introduction to Modern Economics History of Africa South of the Sahara (London: Dent 1976); Terutarō Nishino, “Minami Afurika Zō No Seiritsu Katei: Meiji Ki No Nihongo Kankōbutsu” [How the Image of South Africa Developed: Evidence from Meiji Era Publications], Ajia Keizai [Asian Economics] 11:2 (February 1970): 90-91; Masako Osada, Sanctions and Honorary Whites: Diplomatic Policies and Economic Realities in Relations Between Japan and South Africa (Westport, CT. & London: Greenwood Press 2002); Richard J Payne, “Japan’s South Africa Policy: Political Rhetoric and Economic Realities,” African Affairs 86:343 (April 1987): 167-178; Eric Rosenthal, ed., Encyclopaedia of Southern Africa (London: F. Warne 1961); Rosenthal, Japan’s Bid for Africa: Including the Story of the Madagascar Campaign (Johannesburg: Central News Agency 1944); Keizō Seki, The Cotton Industry of Japan (Tokyo: Japan Society for Promotion of Science 1956); Themba Sono and Human Sciences Research Council, Japan and Africa: The Evolution and Nature of Political, Economic and Human Bonds 1543-1993 (Pretoria, South Africa: 1993); Jones Stuart and Andre Muller, The South African Economy, 1910-90 (London: Macmillan 1992); Imao Tadao, Nan A Renpō Gaikan [A General Overview of the Union of South Africa] (Tokyo: Department of Trade and Commerce 1927); Kojima Takehiko, Kibō Hō Ni Tatsu-Afurika Kikō [Standing at the Cape of Good Hope: A Travelogue] (Tokyo: 1940); Union of South Africa, Debates of the House Assembly, Vols. 17 (1931) and 22 (1934).

5 Rand Daily Mail (RDM), 13 July 1931. The Rand Daily Mail is published by the Anglo American Corp. in Johannesburg.

6 On Japanese-Ethiopian relations see, Richard Bradshaw, “Japanese Interest in Africa: A Historical Overview,” Swords and Ploughshares 7 (1993): 6-8; Bradshaw, “Japan and European Colonialism…,” 1992; Bradshaw, “Japan and European Colonialism in Africa: A Review of the Literature,” in Merrick Posnansky and Yoshida Masao, eds., Reports of the Japanese-American Workshop for Cooperation in Africa (Los Angeles: University of California 1995); Bradshaw, “Japan and British Colonialism in Africa,” in Barry Ward, ed., Rediscovering the British Empire (Krieger Publishers 2001); Bradshaw, “Nihon to Shokuminchi Afurika: Igirusu Teikokushugi o Megutte” [Japan and Colonial Africa: A Focus on British Imperialism], in Kokujin Kenkyū no Kai [Japan Black Studies Association], ed., Kokujin Kenkyū no Sekai [The World of Black Studies] (Tokyo: Seijishobo 2004): 55-95; S. Olu Agbi, “The Japanese and the Italo-Ethiopian Crisis, 1935-36,” Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria 11 (1983): 130-41; J. Calvitt Clarke, Alliance of the “Colored” Peoples of the World: Ethiopia and Japan Before the Second World War, (Forthcoming 2011); Unno Yoshiro, “Dainiji Itaria-Echiopia Sensō to Nihon,” [The Second Italo-Ethiopian War and Japan] Hōsei Riron 16 (January 1984): 190; Okakura Takashi, “1930 Nendai no Nihon-Echiopia Kankei,” [Japanese-Ethiopian Relations in the 1930s] Afurika Kenkyū 37 (December 1990): 61-62; Takashi and Katsuhiko, Nihon-Afurika Kōry-shi…, 1993; Taura Masanori, “I. E. Funso to Nihon Gawa Taio: Showa 10 Nen Sugimura Seimei Jiken wo Chūshin ni” [Italo-Ethiopian Conflict and the Japanese Response], Nihon Rekishi [Japanese History] 526 (March 1992): 79-80; Taura, “Nichi-I Kankei to Sono Yotai (1935-36): Echiopia Sensō wo Meguru Nihon Gawa Taiō Kara” [Italo-Japanese Relations and Their Conditions (1935-36): From the Japanese Response to the Ethiopian War], in Takashi Ito, ed., Nihon Kindai-shi no Sai Kōchiku (Tokyo: 1993); Masanori, “Nihon-Echiopia Kankei ni Miru 1930s Nen Tsūshō Gaikō no Isō” [A Phase of the 1930s Commercial Diplomacy in the Japanese-Ethiopian Relations], Seifu to Minkan [Government and Civilians], Nenpō Kindai Nihon Kenkyū [Annual Report, Study of Modern Japan], 17 (1995):158-59; Aoki Sumio and Kurimoto Eisei, “Japanese Interest in Ethiopia (1868-1940): Chronology and Bibliography,” Ethiopia in Broader Perspectives 1: 713-28; Furukawa Tetsushi, “Japan’s Political Relations with Ethiopia, 1920s-1960s: A Historical Overview,” paper presented to the 35th Annual Meeting of the African Studies Association (Seattle, WA: 20-23 November 1992); Furukawa, “Japanese-Ethiopian Relations in the 1920-30s: The Rise and Fall of ‘Sentimental’ Relations,” paper presented at the 34th Annual Meeting of the African Studies Association (St. Louis, MO: Nov 1991); Furukawa, “Japanese Political and Economic Interests In Africa: The Prewar Period,” Network Africa 7 (1991): 6-7; “Foreign Minister Heruy’s Mission to Japan in 1931: Ethiopia’s Effort to Find a Non-Western Model for Modernization,” Selected Annual Proceedings of the Florida Conference of Historians (March 2007):17-28; J. Calvitt Clarke III, “A Japanese Scoundrel’s Skin Game: Japanese Economic Penetration of Ethiopia and Diplomatic Complications Before the Second Italo-Ethiopian War,” Electronic publication by the XVIth meeting of the International Conference of Ethiopian Studies (Trondheim, Norway: July 2007); Clarke, “Dashed Hopes for Support: Daba Birrou’s and Shoji Yunosuke’s Trip to Japan, 1935,” in Siegbert Uhlig, ed., Proceedings of the XVth International Conference of Ethiopian Studies (Hamburg: Aethiopistische Forschungen 2005); Clarke, “Seeking a Model for Modernization: The Japanizers of Ethiopia,” Selected Annual Proceedings of the Florida Conference of Historians 11 (Spring 2004): 35-51; Clarke, “Mutual Interests: Japan and Ethiopia Before the Italo-Ethiopian War, 1935-36,” Selected Annual Proceedings of the Florida Conference of Historians 9 (February 2002): 83-97.

7 William K. Hancock, The Survey of British Commonwealth Affairs, Vol. 2: Economic Policy, 1918-1939 (London: 1940): Part 1, 211.

8 Osamu Ishii, Cotton-Textile Diplomacy: Japan, Great Britain and the United States, 1930-1936 (New York: Arno Press, 1981): 190.

9 On Anglo-Japanese trade competition in British West Africa see, Hiroshi Shimizu, Anglo-Japanese Trade Rivalry in the Middle East in the Inter-War Period (London: Ithaca 1986); Gilbert Hubbard, Eastern Industrialization and its Effects on the West, With Special Reference to Great Britain and Japan: Japanese Economic History, 3 vols. (London: Routledge 2000); Frederick V. Meyer, Britain’s Colonies in World Trade (London: Oxford University Press 1944) On Anglo-Japanese trade competition in Gambia see, Kweku Ampiah, “British Commercial Policies Against Japanese Expansionism in East and West Africa 1932-1935,” The International Journal of African Historical Surveys 23:4 (1990): 619-641; “Japanese Trade Competition in the Colonies,” 22 February 1934, FO 371/18170 F 982/159/23, PRO.

10 On Anglo-Japanese trade competition in Morocco see, Bird (Casablanca) to Department of Overseas Trade, 9 January 1934, FO 371/18169, PRO; Edmonds to Foreign Office, Dispatch, 17 February 1933, W 2097/175/28: FO 371/17396; Shackle (Board of Trade) to Roberts, Enclosure, 17 August 1939, W 12118/162/28: FO 371/24057, PRO; United Africa Company Ltd. to Foreign Office, Dispatch, 22 February 1933, W 2053/175/28: FO 371/17396; M.M. Knight, Morocco as a French Economic Venture (New York: 1937): 135; Hiroshi Shimizu, Anglo-Japanese Trade Rivalry in the Middle East in the Inter-War Period (London: Ithaca Press 1986): 82, 185, 160, 164.

11 For information on Anglo-Japanese trade competition in Portuguese Africa see, (Consul-General) Francis O’Meara to Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, 31 July 1934, FO 371/18173 F 5304, PRO; Francis O’Meara to Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, 31 July 1934, FO 371/18173 F 5304, PRO; Memorandum on the General Trade and Economic Position of the Colony of Angola in 1935, Enclosure in Consul-General (Francis) O’Meara (Loanda) to Eden, 16 March 1936, PRO 433/3 W 3644/36/36; O’Meara (Loanda) to Department of Overseas Trade, 31 July 1934, PRO FO 371/18173 F 5304; Essentially the same information, with more information on the Japanese trade mission described below, is contained in O’Meara to Department of Overseas Trade, 19 June 1934, PRO FO 371/18173; figures in “Trade Relations Between Japan and Africa,” The Japan Times (Supplement), 31 Oct. 1935.

12 For information on Anglo-Japanese trade competition in Egypt see Richard Bradshaw, “Japan and European Colonialism in Africa, 1800-1937,” Ph.D. diss, Ohio University: 1992.

13 Masako Osada, Sanctions and Honorary Whites: Diplomatic Policies and Economic Realities in Relations Between Japan and South Africa (Westport, CT & London: Greenwood Press 2002): 27.

14 Nunokawa Magoichi, Minami Afurika Bōeki Jijō as cited in Jun Morikawa, Minami Afurika To Nihon: Kankei No Reikishi, Kōzō, Kadai [South Africa and Japan: The History, Structure and Problematic (Nature) of their Relations] (Tokyo: Dobun Kan 1988): 5-6.

15 Dan O’Meara, Volkskapitalisme: Class, Capital and Ideology in the Development of Afrikaner Nationalism, 1934-1948 (Cambridge: 1983): 37.

16 DRO E.4.3.2.2-2; Richard Bradshaw, “Japan and European…,” 1992; Katsuhiko, “Japan’s Trade…,” in Alden and Hirano, Japan and South Africa… 2003: 25-40.

17 Osada, Sanctions and Honorary… 2002: 39.

18 Assembly Debates, 5 July 1931.

19 RDM, 11 July 1931.

20 Arthur G. Barlow in the RDM, 1933.

21 Hedley A. Chilvers, The Yellow Man Looks On: Being the Story of the Anglo-Dutch Conflict in South Africa and Its Interest for the Peoples of Asia, 2nd ed. (London: Cassell and Company 1933): 228-9.

22 “Mrs. Smuts and the Japanese Treaty: Introduction of Yellow Race,” The Rhodesia Herald (Salisbury, Mashonaland: Argus Printing and Pub. Company) 5 Mar 1931.

23 RDM, 13 July 1931.

24 RDM, 15 July 1931.

25 RDM, 14 July 1931.

26 RDM, 17 July 1931.

27 Hansard, XVII, 2 June 1931, 4707.

28 RDM, 8 July 1931.

29 See, T.R.H. Davenport, South Africa: A Modern History (Toronto: University of Toronto Press 1977): 213. 100 pound sterling bought 125 Australian pounds during this period but only 70-75 South African pounds.

30 Takafusa Nakamura, “Depression, Recovery, and War, 1920-1945,” in Peter Duus, ed., The Cambridge History of Japan, vol. 6 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1989): 464.

31Roger B. Beck, The History of South Africa (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press 2003): 109.

32 RDM ,19 Sept 1933.

33 RDM , 19 Sept 1933.

34 RDM, 15 Sept 1933.

35 RDM, 6 Sept 1933.

36 RDM, 19 Sept 1931.

37 Rosenthal, Japan’s Bid…1944: 12.

38 DRO, A 660 1-1-4; Bradshaw, “Japan and European…,”1992.

39 Chilvers, The Yellow Man… 1933.

40 Rosenthal, Japan’s Bid… 1944: 9-10.

41 Hansard, XXII, 7 March 1934.

42 “Sir H.F. Batterbee to Sir George Mounsey,” 1 August 1934, FO 371/18188 B.

43 RDM, 10 Oct 1933.

44 Gilbert Ernest Hubbard, Eastern Industrialization and its Effects on the West With Special Reference to Great Britain and Japan (London: Oxford University Press 1935): 27.

45 George B. Sansom, (Tokyo) “Japanese Trade with South Africa” Enclosure in British Minister F.O. Lindley (Tokyo) to John Simon, 5 March 1934, “Trade Agreement Between Japan and Union of South Africa” PRO FO 2181/159/23.

46 Sansom, “Japanese Trade…” 1934, PRO FO 2181/159/23.

47 Andrew Roberts, “Introduction,” in Andrew Roberts, ed., The Colonial Moment in Africa: Essay on the Movement of Minds and Materials 1900-1940 (Cambridge: University of Cambridge Press 1990): 11.

48 “Minami Afurika Renpō,” [The Union of South Africa] Nihon Gomu Seihin Yūshutsu Kumiai Chōsa Kenkyū [Japan Rubber Products Export Association Investigative Research] 8 (1937): 3.

49 The “onagers” or zebras (valued at f 3,000) arrived in Japan safely aboard the Delftsyhaven. See, E.J. van Donzel, Foreign Relations of Ethiopia 1642-1700: Documents Relating to the Journeys of Khodja Murad (Leiden: 1979): 48 cE.n. 248.

50 Walter Goldfrank, “Silk and Steel: Italy and Japan Between the Two World Wars,” in Edmund Burke III, ed., Global Crisis and Social Movements: Artisans, Peasants, Populists, and the World Economy (Boulder: 1988): 224; Jon Halliday, A Political History of Japanese Capitalism (New York: Monthly Review Press 1975): 128.

51 The Wal-Wal Incident mentioned above.

52 S. Olu Agbi, “The Japanese and the Italo-Ethiopian Crisis, 1935-36,” Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria 11 (1983): 130-41.

53 Sugimura had formerly been deputy secretary‑general of the League of Nations (Osaka Mainichi & Tokyo Nichi Nichi (OM&TNN), 12 Sept 1933).

54 Agbi, “Italo-Ethiopian Crisis…,” 1984: 3.

55 OM&TNN, 20 July 1935. The Osaka Mainichi & Tokyo Nichi Nichi is published by The Mainichi Newspapers Co., Ltd. in Osaka and Tokyo.

56 OM & TNN, 21 July 1935.

57 The Japan Times (JT), 21 July 1935. General Ugaki had arrived in Tokyo on July 8, shortly before the onset of the Sugimura affair, in order to discuss the question of Chosen [Korea]’s budget with government officials in Tokyo. He left Tokyo on July 22 and returned to Chosen on 25 July, “General Ugaki To Visit Genro Today Before Leaving For Chosen,” JT, 24 July 1935; “Ugaki Visits Shimoda On Return To Chosen,” JT, 26 July 1935. While in Tokyo Ugaki was reported as stating that the “impending Italo-Ethiopian war would not be regarded as something on the other bank of the river,” Sugimura to Hirota, 18 July 1935, DRO, File A ET/1-2, cited in Agbi, “Italo-Ethiopian Crisis…,” 1984: 5.

58 OM & TNN, 20 July 1935; JT, 21 July 1935.

59 “Amau Points Out Cases of Italy’s Attack On Japan,” JT, 22 July 1935.

60 “Amau Points Out Cases of Italy’s Attack On Japan,” JT, 22 July 1935.

61 “Amau Points Out Cases of Italy’s Attack On Japan,” JT, 22 July 1935.

62 “Rome Disturbed by Hirota’s Talk To Italian Envoy,” JT, 23 July 1935.

63 “Rome Disturbed by Hirota’s Talk To Italian Envoy,” JT, 23 July 1935.

64 “Japanese Embassy At Rome Is Placed Under Guard; Sugimura To Lodge Protest,” JT, 24 July 1935.

65 As translated in “Japan Pictured As Peril to White Race By Journals,” JT, 24 July 1935.

66 “Japan Pictured As Peril to White Race By Journals,” JT, 24 July 1935.

67 “France Favors Treaty to Grant Italy Protectorate Over Ethiopia; Anti-Japan Demonstrations Seen,” JT, 25 July 1935.

68 “Rome Press Attacks British Move,” JT, 26 July 1935.

69 “Rome Press Attacks British Move,” JT, 26 July 1935.

70 “15,000 Demonstrate Against Japan, Britain,” JT, 27 July 1935.

71 “Rome Quiets Down,” JT, 28 July 1935.

72 “Japan Stand Neutral, Tokyo Informs Auriti,” OM & TNN, 18 Sept 1935.

73 “This Paper’s Network is Completed for News-Gathering in African War,” OM & TNN, 5 Oct 1935: “For a full account of the momentous world drama that is about to be played,” the newspaper advertised, “read the Osaka Mainichi and the Tokyo Nichi Nichi.”

74 These included Edward W. Beattie, Webb Miller, Percival Phillips, Leonard Packard, Alfred Street, Herbert Ekins, and Ladislas Farago, see, “This Paper’s News Front in Africa Vitalized to Meet All Emergencies,” OM & TNN, 3 Sept 1935; Ladislas Farago, “Native Drums Call Tribes to Arms…,” OM & TNN, 24 Sept 1935.

75 Wallington (Pretoria) to Wiseman, 6 Aug 1935, PRO, FO 371/19367. It is not known whether Wada actually entered into negotiations for broadcasting rights. Wada returned to the U.S. at the end of August, see “Staff Correspondent Back,” 3 Sept 1935, PRO, FO 371/19367.

76 OM & TNN, 24 July 1935.

77 J. Calvitt Clarke, Alliance of the “Colored” Peoples of the World: Ethiopia and Japan Before the Second World War, (Forthcoming 2011), 235.

78 J. Calvitt Clarke, Alliance of the “Colored” Peoples of the World: Ethiopia and Japan Before the Second World War, (Forthcoming 2011), 235.

79 See Hugh Byas, Government by Assassination (New York: Knopf Publishers 1942): 200. The Amur River Society is often referred to as the “Black Dragon Society” because the literal meaning of the Chinese characters for the Amur River are “Black Dragon”. The society took the name of the Amur because of its initial goal to prevent the Russians from extending their influence beyond that river in Manchuria. To call it the “Black Dragon Society” downplays the importance of the river after which it was named and tends to exaggerate the reputedly sinister, secret nature of the society.

80 Auriti called on Horinouchi in the absence of Foreign Minister Arita Hachiro, see, “Italian High Commissioner At Addis Ababa To Be Told To Respect Japanese Rights,” OM & TNN, 14 May 1936.

81 Arita to Sugimura, 27 June 1936, DRO File A 461 ET/13-1, cited in Agbi, “Italo-Ethiopian Crisis…,” 1984: 8. Agbi’s footnote 44 contains the correct reference, not footnote 43 as the paper incorrectly indicates.

82 Sugimura to Arita, 14 October 1936, DRO File A 461 ET/1-15, cited in Agbi, “Italo-Ethiopian Crisis…,” 1984: 9, cf. n. 46.

83 Sugimura to Arita, 18 November 1936, DRO File A 461, ET/1-15, cited in Agbi, “Italo-Ethiopian Crisis…,” 1984: 9, cf. n. 47.

84 Sugimura to Arita, 2 December 1936, DRO File A 461 ET/1-15, cited in Agbi, “Italo-Ethiopian Crisis…,” 1984: 10, cf. n. 48.