Two Generations of Japanese and Japanese American Artists: Activism, Racism and the American Experience

Roger Pulvers

This article profiles the extraordinary story of two generations of Japanese and Japanese American artists—graphic artists, and a TV actor and theatre producer—in Japan and the United States across the divide of World War II. It offers observations on activism and opportunity through profiles both of success and the limits of Japanese integration on the American screen in Hollywood and TV.

Taro Yashima: an unsung beacon for all against ‘evil on this Earth’

A little boy cannot be found at his village school. He is hiding under its floorboards. His name is Chibi, which means “little tyke.” He cannot make friends. The other children will not play with him.

Chibi stares at the ceiling for hours. He loves all kinds of yucky insects. No one can read his handwriting. Everyone calls him “stupid” and “slowpoke.”

But when he is in the sixth grade, a new teacher, Mr. Isobe, recognizes his talents. Chibi is so intimately in touch with nature that he can commune with it. One day he performs for Mr. Isobe and all his classmates, revealing his hidden gift. Chibi can imitate the voices of crows, from the calls of hatchlings to those of the mother and father crow.

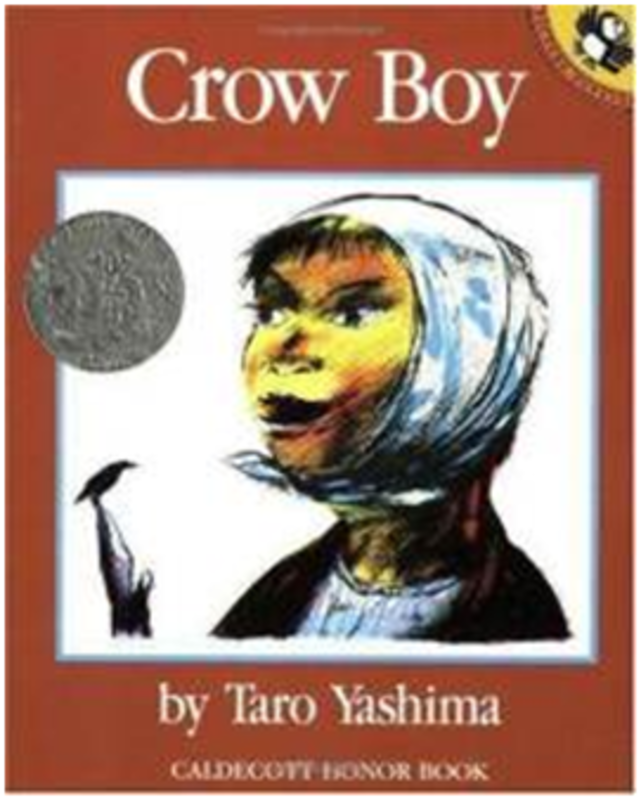

This is the story of “Crow Boy,” written and illustrated by Taro Yashima.

Yashima’s is not a name that many Japanese readers, even those of children’s books, are likely to be familiar with today. But his own story is remarkable and, in spirit, not unlike that of his creation, Chibi.

He was born Iwamatsu Atsushi on Sept. 21, 1908, in Nejime, a small village on the coast near Cape Sata, where Kagoshima Bay, in southern Kyushu, flows into the ocean. (Nejime has now merged into the larger entity of Minami Ōsumi-cho. His father was the village doctor and an ardent collector of Asian art. Mr. Isobe in the story is modeled on two of the author’s teachers at Kamiyama Elementary School —Isonaga Takeo and Ueda Miyoshi.

The young Yashima exhibited significant talent as an artist. At age 13, his satirical manga were being published in the Kagoshima Shimbun daily newspaper, today’s Minami Nihon Shimbun. At 19, he gained entrance to Tokyo Bijutsu Gakkō,Tokyo School of Fine Arts, in Ueno. (That school merged, in 1949, with Tokyo Ongaku Gakkō, Tokyo Music School, becoming today’s Tokyo Geijutsu Daigaku, Tokyo University of the Arts.)

Yashima refused to participate in military exercises at the school and, in 1929, he was expelled for insubordination. He became an active participant in anti-fascist political causes and sketched the death mask of the proletarian writer Kobayashi Takiji when the latter’s corpse was released by his jailers with visible signs of torture on it.

Yashima himself was also repeatedly jailed and beaten in prison for his political activism, as was his wife, Tomoe, whom he had married in 1930.

Finally, in 1939, both managed to leave Japan for the United States, where they arrived in New York having left their 6-year-old son, Makoto, with his grandparents in Japan. Yashima wasn’t to see his son until after the war, when he returned, in 1945, as a member of a U.S. strategic bombing survey team.

In New York, both the Yashimas continued their art studies at the prestigious Art Students’ League on West 57th St. But when war broke out between the U.S. and Japan following the Pearl Harbor attack on Dec. 7, 1941, Yashima enlisted in the U.S. Army and was posted first to the Office of War Information and then to the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the predecessor of the CIA.

It was then that the Yashimas abandoned the birth-name Iwamatsu, for fear of repercussions against their son and parents in Japan. Being so fearful of retribution back home, Tomoe — whose prewar pen name was Arai Mitsuko — took on the name Mitsu.

Yashima spent some months of the war years in India on intelligence missions. Upon his return to the U.S. he wrote and illustrated handbills in Japanese that were dropped over battlefields bearing the phrases “Don’t Die!” and “Papa, Stay Alive.” To charges in Japan that he was a traitor, he later remarked that his sole aim was to save Japanese lives.

“At the time it was easy to say I was one who was against his own country,” he explained. “That’s the most terrible thing, because my feeling was, I’m doing it because I love my country.”

It is that genuine love of country, so powerful that it urges people to act against its evil excesses, that is rarely celebrated in Japan. It did exist, and the lives of Taro and Mitsu Yashima attest to it.

Yashima published two illustrated autobiographical books in the 1940s, “The New Sun” in 1943 and “Horizon is Calling” in 1947. In those he detailed his and his wife’s maltreatment by the Japanese secret police. Yet he also conveyed what he considered his message to Americans at the time: that all Japanese are not “wild monkeys.”

Several picture books followed in the succeeding decades, including “The Village Tree” in 1953, “Crow Boy” in 1955 and “Seashore Story” in 1967. The tree in “The Village Tree” is the home of “all sorts of bugs on the leaves, and places to play in the branches.” That book, and all the others by Yashima, hark back to a Japan in which nature was cherished and children felt it to be their constant friend.

In 1948, Makoto joined his parents in the U.S., and Mitsu gave birth to a daughter, Momo. As Momo grew up, her parents created exquisite picture books for her, such as “Momo’s Kitten” and “Umbrella.” I love “Umbrella.” It captures the simple thrill of a little girl who gets an umbrella for the first time. When she grabs hold of it, she lets go of her parent’s hand, the first sign of self-reliance.

By 1954, the Yashimas were living in Los Angeles, having settled in the poor Boyle Heights district of the city. They established the Yashima Art Institute, where they taught. But the couple separated, and Mitsu moved to San Francisco, where she lectured at the University of California, Berkeley, on “People’s Art in Japan” and taught art, in the 1970s, at Kimochi, a community center in the city that continues to bring together younger and older Japanese Americans.

At that time, too, Mitsu — having never forsaken her activism — took part in the Women Strike for Peace movement against nuclear weapons and the Vietnam War.

Taro Yashima suffered a stroke in 1977, eventually passing away in hospital in Los Angeles in 1994. His motto for his books should inspire young people around the world today: “Let children enjoy living on this Earth, let children be strong enough not to be beaten or twisted by evil on this Earth.”

In 1983, Mitsu returned to Los Angeles to live with Momo, who had become an actress. (Momo Yashima Brannen was in the 1979 movie “Star Trek: The Motion Picture,” and has had roles in television shows including “The Beverly Hillbillies,” “L.A. Law” and “ER.”) Mitsu’s death in 1988 preceded her husband’s by six years.

Yashima’s works are held in Japan primarily at the Iwasaki Chichiro Art Museum, which has two sites — in Nerima Ward, Tokyo, and in Azumino, Nagano Prefecture; and at the Kagoshima City Museum of Art.

|

Yashima watercolor |

|

Book signing for children |

The artwork in the couple’s books is lovely. He worked primarily in watercolor and ink; she in charcoal, pencil and soft pastels. The stories themselves have qualities of natural wonder and self-discovery that children in today’s world of shock and dysfunctionality would surely benefit from encountering.

As for the Yashimas’ son, Makoto, he became the famous screen and stage actor Mako Iwamatsu.

Mako: the Japanese American actor who fought racist stereotypes

When “The Green Hornet,” the old radio and comic book series about the masked white vigilante, was turned into a television series in 1966-’67, Japanese American actor Mako played the Chinese Low Sing, while Chinese American and Hong Kong actor Bruce Lee played the Japanese Kato. You gotta love Hollywood! It has never mattered very much to the moguls of schlock “what part Asia you from.”

The race barrier for blacks in film has been broken for decades, thanks to the pioneering work of such brilliant actors as Dorothy Dandridge, Sidney Poitier and others. Roles for blacks are no longer race specific. Black actors have played top spies and presidents. Morgan Freeman has even played God.

But the last and most stubborn racial barrier in Hollywood is the Asian one.

Mako, whose full name was Iwamatsu Makoto, was born on Dec. 10, 1933 in Kobe, the son of the Yashimas. The Yashimas left Japan in 1939 for New York and were not able to bring their son to the United States until well after the war.

I met Mako 30 years ago. He approached me with the proposition of producing my play, “Yamashita,” at the theater he had established in Los Angeles in 1965, East West Players. “Yamashita,” which takes place in Hawaii in 1959, is a play about racism and the scar tissue left in the minds of the victims of war. (The play ran in their 1982-’83 season.)

|

Mako was ever bitter about the way film and television producers stereotyped Asians. He was an actor with an immense gift for portraying compassion on screen; but he could be your cruel avenger at the drop of a hat, as well. Yet, the roles he was given were almost entirely race specific: a string of Asians from all over the continent and region as a foil for the great white hero.

Shortly after arriving in the U.S., Mako enlisted. His father had served in the U.S. military. In addition, special naturalization provisions for non-Americans serving in the U.S. armed forces had been in place since the Civil War. (He naturalized in 1956.) It was in the army, while performing for his buddies, that Mako became aware that he had acting talent.

After leaving the service, with his family now living in Los Angeles, he took up study at the Pasadena Playhouse, a school of the theater arts that has produced major talents over many decades. While actors such as Ernest Borgnine, Charles Bronson, Gene Hackman and Dustin Hoffman left the Pasadena Playhouse to shoot to the top of their profession, Mako was offered roles “befitting his background.” He became determined to break through the bamboo curtain and be seen as an actor, first and last.

Between 1962 and 1964, he played various types of Japanese soldiers opposite his Pasadena Playhouse friend Ernest Borgnine in the popular TV series about a U.S. PT boat in World War II, “McHale’s Navy.” But his big break came in 1966, when he acted with Steve McQueen, Richard Attenborough and Candice Bergen in “The Sand Pebbles.”

“The Sand Pebbles” is a film about an American gunboat on the Yangtze River in the mid-1920s in China. Mako was Po-han, a tough Chinese working in the engine room. This role brought him a nomination for an Academy Award as Best Supporting Actor.

|

Po-han in The Sand Pebbles |

A number of parts came his way on television, where, as in “M*A*S*H” in the 1970s, he portrayed Koreans from both sides of the Demilitarized Zone and a Chinese.

But I think that Mako was most at home around a stage. He was a totally hands-on artistic director at East West Players, which he ran with his actress and dancer wife Shizuko Hoshi. And he fought hard to get the part of the Reciter in Steven Sondheim’s 1976 Broadway musical, “Pacific Overtures,” which told the story of Perry’s 1853 expedition to Japan.

|

Mako playing the Reciter in “Pacific Overtures” on Broadway, 1976 |

“We couldn’t let people say Asian American actors can’t act,” he said.

Mako had a career in Japan as well, though, as was the case with his predecessor in Hollywood, Sesshu Hayakawa, he was never taken back into the Japanese fold and offered the kinds of major roles his talent deserved.

He first appeared in Japan in 1967, in the TBS TV drama “Naite Tamaru ka” together with famous actor Atsumi Kiyoshi. Other roles followed, such as that of pre-Meiji Era (1868-1912) interpreter John Manjiro in “Tennō no Seiki” in 1971. Film director Miike Takashi used Mako to play a Chinese named Shen in a remote Chinese village in his 1998 film, “The Bird People in China”; and Shinoda Masahiro directed him as the daimyo warrior Hideyoshi in his 1999 movie, “Fukuro no Shiro” (“Owl’s Castle”), based on the Naoki Prize-winning novel by Shiba Ryōtarō. But, in many senses, Mako was just as much an exotic figure to the Japanese as he was to the Americans.

Small roles in films with stars such as Charlton Heston, Robert Duvall, Arnold Schwarznegger and even Brad Pitt kept Mako in Hollywood’s eye. He appeared as Admiral Yamamoto Isoroku in the 2001 war blockbuster “Pearl Harbor.”

|

Mako as Adm. Yamamoto |

“Tatakau shika nai!” (“We have no choice but to fight!”) he says to his cohorts in that film, informing them that Japan was going to attack the U.S. But the leading role that he craved as an actor never came his way in either of his two homes.

One of my favorite performances of his is as Tan the grandfather in the 2007 film made in Singapore, “Cages.” This is a film about a little blind boy who always smiles; and Mako overwhelms us with his tenderness and grace in it.

“I’ve always been more interested in character development, more than plot or action or special effects,” he said of this and, by extension, all his roles.

|

“The Sorcerer” with Schwarznegger as Conan |

In his last years he endeared himself to a new generation of audience as a voice actor in animated TV series, particular in the role of Aku, “the evil shape-shifting master of darkness” in “Samurai Jack,” and as Iroh, the legendary Fire Nation General in “Avatar: The Last Airbender.”

Mako passed away in the small town of Somis, California on July 21, 2006, leaving his wife, two daughters, three grandchildren and his sister, actress Momo Yashima Brannen.

Once, when he was nominated for a Tony Award for Best Actor in a Musical (“Pacific Overtures”), he had an unpleasant experience on the way home from the ceremony. He was still wearing his kabuki-style costume when someone on the street hollered, “Hey, why don’t you go back to China!”

He said later he would have refused the Tony had he won it.

“Why? Asian American actors have never been treated as full-time actors. We’re always hired as part-timers … for race-specific roles. … I didn’t feel I could accept the award as long as Asian Americans were not treated (as equals) in our profession.”

Mako goes down in history not only as a world-class actor and theater producer, but also as a warrior for the civil rights of all minorities oppressed by ingrained racist stereotypes of a majority.

Epilogue

One massive wall crumpled. The solid all-white marble wall that kept black actors out of leading roles in Hollywood films came down several decades ago, as I point out in the essay above. But, the wall of prejudice against Asians taking non-race-specific leads in movies seems to be impregnable. Japanese American actor Mako, for one, spoke bitterly of being barred from the kinds of roles he craved.

How did African Americans break through? It was thanks, no doubt, to the civil rights movement that came to an active head in the 1960s. Their move into leading roles in film came concomitantly with their advances into the mainstream of American society as equals, notably in the professions, the arts—on both stage and screen—and, from earlier, in sports.

Something else had been happening in the American entertainment business from the early 1950s. Roles for black actors in film and television that came to be seen as demeaning, even when they were not meant to be, became unacceptable. “Amos ‘n’ Andy,” which started off as a radio series and made the switch to TV in 1951, was considered non-PC and was dropped, first, perhaps, because the two creators of the original radio show in 1928, Freeman Gosden and Charles Correll, were white; and second because the types of characters depicted in the series came to be seen as derogatory representations of black people. The NAACP spearheaded the campaign against this show. This was even despite the fact that such great actors as Tim Moore and Alvin Childress, who appeared in “Amos ‘n’ Andy,” were icons of black comedy.

Jack Benny came under fire in the mid-sixties for using brilliant comedian Eddie Anderson in the part of Rochester, his valet, though Benny was in no way anti-black.

Did Asian American actors—or the Asian American community in general—ever organize to protest stereotyping against them? I am unaware of anything like this on a major scale, and would appreciate hearing from readers who might have some information to the contrary. Some, like Mako and Miyoshi Umeki, were bitter. Umeki went so far as to quit show business. (For more about her, see my Japan Times Counterpoint article here.)

I think the reason why Asian Americans have never broken through Hollywood’s bamboo curtain is that, as a group, they have been historically passive in American society, largely seeking respectability rather than kudos for conspicuous and activist participation. This was particularly true of the Nisei community in L.A., where I grew up. Perhaps the Japanese brought with them their non-confrontational attitudes and their neo-Confucianism. Perhaps they still lived in the shadows of World War II and the stigma of “the sneak attack” on Pearl Harbor. They were not known for self-assertiveness. The Chinese, too, seemed socially silent when it came to the entertainment industry. Whatever the reasons—and despite absolute gains overall in education, science, business, income and integration in American society—the bamboo curtain seems to remain intact in Hollywood today. Roles for Asian American actors are largely race specific and frequently subordinate. When the curtain is finally brought down, Asian Americans will have Mako to thank for pulling the ropes.

This is a revised and expanded essay drawing on two articles that appeared The Japan Times on September 11 and September 18, 2011.

Roger Pulvers is an American-born Australian author, playwright, theatre director and translator living in Japan. An Asia-Pacific Journal associate, he has published 40 books in Japanese and English and, in 2008, was the recipient of the Miyazawa Kenji Prize. In 2009 he was awarded Best Script Prize at the Teheran International Film Festival for “Ashita e no Yuigon.” He is the translator of Kenji Miyazawa, Strong in the Rain: Selected Poems. The Dream of Lafcadio Hearn is his most recent book. He will talk, sponsored by The Japan Society, London, on October 24, and in Dublin on October 26, sponsored by the Ireland Japan Association, on “The Dream of Lafcadio Hearn: How did this Greek-Irishman conquer Japan?”

Recommended citation: Roger Pulvers, ‘Two Generations of Japanese and Japanese American Artists: Activism, Racism and the American Experience,’ The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 9, Issue 38 No 3, September 19, 2011.